Albrennia

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Commonwealth of Albrennia | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Hope" | |

| Anthem: I Vow To Thee, My Country | |

Location of Albrennia | |

| Capital | Providence |

| Largest city | Wellfleet |

| Official languages | Rythenean |

| Ethnic groups | By ethnicity:

|

| Demonym(s) | Albrennian |

| Government | Unitary Presidential Matthean Republic. |

• Chancellor | Thomas Goodwin (R) |

• Vice Chancellor | William Ames (R) |

• Majority Leader | Nicholas Byfield (C) |

• Chief Justice | Catherine Noyes |

| Legislature | Parliament of the Commonwealth |

| Stages of Independence from | |

• Instrument of Governance | 15 May 1539 |

• Congress of Wedayen | 7 October 1816 |

• 12th Amendment to Instrument of Governance | 10 February 1817 |

• Treaty of Delhaven | 21 July 1825 |

| Area | |

• Total | 2,019,286 km2 (779,651 sq mi) (5th) |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 80,631,224 (4th) |

• 2015 census | 79,130,514 |

• Density | 39.9/km2 (103.3/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $5.159 trillion (1st) |

• Per capita | $63,985 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $5.275 trillion (1st) |

• Per capita | $65,426 |

| Gini (2020) | high |

| HDI (2020) | very high |

| Currency | Albrennian Guilder (ALG) |

Albrennia, officially the Commonwealth of Albrennia, colloquially often simply the Commonwealth, is a sovereign state and presidential republic in Northeast Marceaunia Major. Situated on the Albren Peninsula, of which it is geographically coterminous, Albrennia is bordered by the Hesperian Ocean to the east, north, and south; by the Gulf of Colrain to the southwest; by Rowlands Bay to the northwest; and by the Lamont Range and [???] to the west. The Commonwealth is a unitary state consisting of of nine major metropolitan administrations and 4,352 rural townships, which together cover an area of 2,019,286 square kilometers (779,650 sq mi) and encompass an estimated population of 80,631,224. It is the fourth-largest nation in Levilion by population, and the fifth-largest by area.

The Albren Peninsula was inhabited by North Marceaunian indigenous peoples from at least 3000 BCE. In 1460, the Rythenean explorer Rufus Albren discovered the peninsula, and all of Marceaunia along with it. From 1504, Rotiferist colonists from Rythene, committed to a heterodox and predestinarian strain of Perendism, settled the Albren Peninsula and established the oldest Auressian society in the New World - driving the indigenous population west of the Isthmus of Lamont in the process. Albrennia remained a Rythean colony for more than three centuries, but its republican government enjoyed substantial autonomy, and it became a center of global trade with a renowned merchant culture. It supported the Rythenean Revolution, contributed directly to the Rythenean war effort, and was granted independence in 1816 at the Congress of Vedayen in order to weaken Rythene's colonial empire.

In the nineteenth century, Albrennia rapidly industrialized and became a major hub for immigration from Auressia and Marceaunia Minor. It intervened repeatedly in Marceaunia Minor: pioneering a new brand of economic imperialism based on private companies' control of natural resources, and developing one of the world's most powerful navies - known simply as the Fleet - to defend its far-flung holdings. In the Panic of 1876, Albrennia suffered a devastating economic collapse, in the wake of which its economy became dominated by a small number of enormous, vertically integrated corporate conglomerates: the Pillars. The dominance of the Pillars generated a wave of labor unrest, finally resolved by the development of the economic and political structure known as the Matthean System. Albrennia was a member of the Coalition in the Great War and of the Allies in the Second Great War, and its naval power made an important contribution to victory in both conflicts. By the end of the twentieth century, Albrennia was a global center of finance and manufacturing, a naval power with reach across Levilion, and a key player in the global economy with interests and investments on every continent.

Albrennia is a unitary presidential constitutional republic, but international observers note its lack of political transparency and accountability, and Albrennian politics tend to be dominated by the Pillars, organized labor, and the permanent civil servants known as the Establishment. Albrennia is a founding member of the Assembly of Marceaunian States (AMS) and has economic, diplomatic, and military agreements with foreign governments around the world; it is especially active in resource-rich smaller nations. It is a confirmed nuclear weapons state and a naval power with few equals and no superiors; the Fleet receives more than 50% of government spending in an average year. It is officially recognized as a great power.

Albrennia is a developed country with Levilion's largest single economy both by nominal GDP ($5.275 trillion) and by purchasing power ($5.159 trillion) - though the overall economy of the Commonwealth of Northern Auressia is much larger than Albrennia's. The Albrennian economy is dominated by manufacturing (especially arms manufacturing and shipbuilding), the electronics and informatics industry, finance and insurance, healthcare and pharmaceuticals, and science and technology. Albrennia has few natural resources and is the largest importer in Levilion; it also has the highest rate of investment in foreign nations as a percentage of GDP. It is noted for the Matthean System, in which each sector of the economy is dominated by a single corporate "Pillar" and a single compulsory labor union, and government-mediated corporatist negotiations between the Pillars and organized labor define wage floors, healthcare benefits, and other social welfare programs. The system has provided Albrennian workers with a high standard of living, reflected in the nation's very high Human Development Index. But income inequality between the middle and upper classes remains high (Albrennia has more than 500 billionaires), and the Matthean System means that long-term household-wide unemployment can result in extreme poverty. Albrennia is regarded as an educational leader, with two of the ten highest-ranked universities in Levilion, and it has made major cultural contributions in the fields of music, film, and academic scholarship.

Etymology

Albrennia is named for Rythenean explorer Rufus Albren (1418-1469), who in 1460 discovered Maurceania when he made landfall near modern Sherborn. His subsequent voyages charted the outline of the Gulf of Colrain and Rowland's Bay. By 1490, early maps show that the hammerhead-shaped peninsula of northeastern Marceaunia Major was known as Albren's Land (later the Albren Peninsula). This was Sabarinized in official documents to become Albrennia. While many of the initial Rotiferist settlers wanted their new land to be called Rotifia, and while that name remains in occasional use as a rhetorical reference to traditional Albrennian values, it never caught on widely. Instead, by the 1530s, Rytheneans were referring to the colony as Albrennia - and, notably, to its inhabitants as Albrennians rather than Rytheneans. As the colonists came to think of themselves as Albrennian, so inevitably they came to think of their land as Albrennia. The 1539 Instrument of Governance - the origin of the Albrennian polity - declared that the government of the colony was "His Majesteie's Most Loyal Albrenyan Republicke." Ever since, Albrennia has been the only name used for the nation.

Albrennia is a "Commonwealth" in the historical sense: it is a republic, and "commonwealth" is a literal translation of the Ancient Sabarine res publica, a "public thing" or "shared thing." It is meant to indicate that the government is the shared business of all the citizens, and this meaning has been preserved by democratic reformers and labor activists throughout Albrennian history. Today, many Albrennians refer to their country simply as the Commonwealth, and in Marceaunia this term by itself is generally understood to mean Albrennia, not the Commonwealth of Northern Auressia. More rarely, Albrennians may shorten their country's name to Albren: this is most common in official contexts, and is understood to suggest a certain poetic and nationalist flair. A citizen of Albrennia is an Albrennian, and that term is also correct as applied adjectivally: "Albrennian ships," for example.

History

Indigenous Peoples and Early Settlement

It has been generally accepted that the first inhabitants of Marceaunia Major migrated from Marceaunia Minor by way of the Adrienne Land Bridge at least 12,000 years ago. By 4,000 years ago, the Paleoaborigines were present in the Albren Peninsula. Archeologists initially believed that the Harpswell Culture represented continuous habitation of the population by the same peoples ever since; it is now thought to be likely that the Harpswell Culture reflects merely the last of multiple waves of migration into the peninsula.

Over time, indigenous culture and political organization in the Albren Peninsula grew increasingly complex. Agriculture became the basis of life: villages composed of longhouses, each housing an extended family unit, were surrounded by fields of maize and beans. Some time between the twelfth and the fifteenth centuries, a great prophet named Dekkenorhawi led a religious revival, put an end to the practice of ritual cannibalism and the internecine warfare associated with it, and bound the tribes of the peninsula together into the Hathawekala Confederacy.

In 1460, the Rythenean explorer Rufus Albren made landfall near modern Sherborn, and became the first Auressian to set eyes on Marceaunia. In three subsequent voyages, he would successfully map the Albren Peninsula. Over the next forty years, Rythenean traders came into regular contact with the Hathawekala Confederacy. They brought disease as well as cooking pots and axes, and epidemics of smallpox and measles ravaged the area, reducing the Hathawekala population by half by 1500.

Meanwhile, Rythene found itself in religious turmoil. Following a reformist preacher named Walter Hartcliffe, a new branch of Classical Perendism had emerged: the Rotiferists. Meaning literally "those who follow the direction of the wheel," this term referred to a predestinarian movement. Hartcliffe preached that everything that really matters about the Earth is inevitable and irresistible: the changing of the seasons, the movement of the stars, the tide, the cycle of life and death. Therefore, spiritual balance cannot actually be within the attainment of the individual. All that a man can do is submit himself to the world, to understand its processes and surrender to them. If God so wills it, he will achieve balance, just as the sun rises and the winter turns to spring. If God does not will it, then "not every tree survives the winter," in the old Rotiferist aphorism.

Rotiferism inspired certain distinctive values. Since Rotiferists were constantly and anxiously examining themselves for signs that they were indeed in balance with the world, the denomination acquired a reputation for self-discipline and extremely hard work - the supposed signs of a balanced soul. Since they claimed to derive their predestinarian beliefs by rational deduction from the natural world, they regarded education and literacy as a sacred duty. The movement was dominated by the educated merchant classes, who considered their prosperity a sign of God's balancing work within them. In Rythene, as this reformist proto-bourgeosie ran up repeatedly against the aristocratic elite's hold on politics and religion, it came to feel that the only way to build a truly godly and balanced society was to start over.

In March of 1504, the caravel Springsong sailed from Delhaven with some three hundred Rythenean Rotiferists aboard. They had a safe crossing, and established a settlement at Newhaven. The Hathawekala Confederacy had fallen into disarray under the pressure of epidemic disease, and the colonists were able to play different indigenous factions off against each other, offering the aid of soldiers armed with steel weapons and horses in exchange for food and knowledge of local conditions. By 1515, the colony was firmly established and had begun attracting thousands of immigrants from Rythene per year: this influx consisted mostly of Rotiferists, but it also included many Classical Perendist families who simply wanted free land. By 1530, the eight original cities of the Commonwealth had been founded along the rocky Hesperian seaboard: Newhaven, Tolland, Alford, Colrain, Wellfleet, Lanesborough, and Sherborn. Within a generation of its founding, Albrennia had become self-sufficient in food and raw materials from Rythene. It was a functioning society in its own right.

Colonial Albrennia

Albrennia was a colony of Rythene for 312 years: well over half of its history. It was the oldest Auressian colony in the New World, and the first to develop sophisticated institutions of its own: by the time the first Tyrnican colonists settled in what is now Audonia, Newhaven had been a major city for almost two centuries. Alford and Tolland Universities, both established in the 1540s, are older than many prestigious institutions on the other side of the Hesperian. The Instrument of Governance adopted by the colony in 1539, and reluctantly ratified by the Rythenean crown two years later, provided for a democratically elected Assembly and Governor. Since the Albrennian Constitution of 1816 only slightly amended the Instrument of Governance to make it suitable for an independent nation, Albrennia has long claimed to have the oldest continuous democratic tradition in the world.

The colony's expansion was slow but steady, pushing the remnants of the Hathawekala beyond the mountains of the Isthmus of Lamont. This was a process of mass ethnic displacement, but the colonists attempted neither assimilation nor extermination of the natives: their goal was to remove the Hathawekala to the interior of Marceaunia Major, not to annihilate them. This was because, already by 1550, Albrennia's culture had evolved to orient it toward the sea; colonists had no desire to press on beyond the Isthmus, because and the promise of trade was more alluring that the dangers of further expansion. This campaign of mass displacement explains why very few Native Marceaunian communities, or even individuals of Aboriginal descent, remain in Albrennia today.

As a result of the colonists' limited territorial ambitions, Albrennia ceased to be a frontier society more quickly than many New World colonies. Safe behind its natural border along the Lamont Range, and rendered homogenously Auressian by the mass displacement of the Hathawekala to the west, its economy thrived as it turned the vast pine forests of the Albren Peninsula into a fleet of sailing ships. Those ships, in turn, became the backbone of much of the colonial trade that connected many Auressian nations to their colonies: carrying slaves to Marceaunia Minor, and carrying sugar and rice and coffee and tobacco from the New World back to Auressia. Rythene's 1622 International Market Act, which allowed upper-class Rytheneans (including Albrennians) to trade with the rest of Auressia, was essential to the colony's prosperity: it permitted Albrennian shipping to serve as a crucial link between the New World and the Old, not just between Rythene and its colonies. Most Auressians, by the mid-seventeenth century, no longer really thought of Albrennia as the frontier: it was a place of universities, coffee shops, busy trading ports, and century-old cities - a little piece of the Old World on the shores of the New - and its legions of merchants were a common sight in ports on every shore of the Hesperian.

But as Albrennia became a more established and comfortable place, so too did it change in the process. By the eighteenth century, the voyage of the Springsong was already two centuries in the past, and the Rotiferist majority was consigned to history. Generations of immigrants had come seeking not a godly society but economic opportunity: cheap land, and work on the docks, and the chance to sail the world with the Albrennian merchant marine. While most immigrants continued to hail from Rythene, there were far more Apostolic and mainstream Classical Perendists than Rotiferists. And increasingly, the major cities of Albrennia became a magnet for immigration from Blayk, Vervillia, and Tyrnica as well. The colony remained majority-Auressian only because, while Albrennian merchants were central to the slave trade, slavery itself was banned in Albrennia.

This prohibition testified to the lingering cultural influence of Rotiferist values, even as Albrennia became less and less religiously homogenous. Those values had other consequences, too. Despite constant encroachment by the royal court of Rythene, Albrennian politicians successfully defended their republican colonial government, and old Rotiferist families continued to dominate the colonial capital at Newhaven. From 1624, Albrennia required municipalities to fund the world's first system of universal primary education, a testament to the centrality of learning in Rotiferism; the great universities of Tolland and Alford, though, remained the preserve of the same old Rotiferist families that controlled the colony's government. Rotiferist values of competition and self-improvement led the colony to abandon all mercantilist protections other than those imposed by Rythene, creating one of the freest markets in the world and turning Albrennian harbors into centers of global commerce. To secure the global trade network that had evolved, the Albrennian Assembly created the Albren Bank in 1757: one of the world's earliest central banks, created not by a sovereign crown but by a mere colonial government. Its purpose was to give the colonial government additional liquidity to support Albrennian companies, by issuing bank notes secured against the government's loans. Albrennia would remain a leading player in global finance forever afterwards.

Independence and Marceaunian Engagement

By the late eighteenth century, Albrennia was already a country of six million souls. It had its own global trading networks and well-developed political institutions, and almost three centuries of its own history. In 1786, Charles IV of Rythene revoked the 1622 International Market Act. This was a fatal threat to Albrennian trade networks, and it infuriated the old Rotiferist elite and the more secular merchant classes alike. Accordingly, when the Rythenean Revolution erupted in 1790, support for the new Republic was almost universal in Albrennia. In turn, the 300-year republican tradition of Albrennia's colonial government earned the colonists a level of respect unique among the Republic's colonies.

And so, while every other Auressian colony in Marceaunia succesfully rebelled between 1790 and 1820, Albrennia remained politically bound to Rythene - albeit that many Albrennians now saw that relationship more as an equal partnership than a colonial yoke. In the War of the Commons, the colonial government nationalized hundreds of merchant vessels and their experienced crews - an act that would go down in history as the origin of the Fleet. This new naval force sailed all the way across the Hesperian Ocean to engage the Tyrnican navy in pitched battle in the Galene Sea. When the conflict finally ended, it was clear to the victorious monarchists that Albrennia was too important an asset to be allowed to remain in Rythene's hands, but that it was also too powerful in its own right simply to be transferred to another colonial power. The Congress of Vedayen (1816) saw Albrennian independence as the simplest solution to an insoluble problem, and so the Commonwealth gained its sovereignty not on the battlefield but as a grudging gift of its erstwhile enemies.

Independence brought few immediate changes after 1816. By the 12th Amendment to the Instrument of Governance, Albrennia's colonial governor became the chancellor, its assembly the parliament, and references to the Crown of Rythene were removed; otherwise, politics continued very much as before. But the coming decades would be more tumultuous.

Albrennia began rapidly to industrialize from the 1820s on: a dense network of canals, railroads, textile mills, and eventually armaments factories sprang up, taking advantage of iron and coal deposits in the Lamont Range of western Albrennia. The accelerating demand for labor that resulted, together with Albrennia's political stability in an unstable era, brought another wave of immigration: this time more from Tyrnica and Palia than from Rythene. As Albrennian manufacturing boomed, the Commonwealth began to look abroad for markets, and so it was drawn into the tumultuous affairs of Marceaunia Minor.

The Continental War (1831-1836) witnessed the defeat of the Confederation of Southern Marceaunia by the Aillacan-Rocian Union, followed by the Confederation's collapse altogether. Albrennian companies profited greatly off the war by selling arms and supplies to both sides; Albrennia's status as one of the world's largest arms dealers dates to this period. But when the conflict ended, the real victor was the Free Republic of Audonia: the collapse of the Confederation left Audonia as the dominant commercial and naval power in Marceaunia Minor.

The next twenty-nine years witnessed a contest for influence between Albrennia and Audonia in the emerging markets of the Southern Hemisphere. Albrennian tactics were ruthless, and by the 1850s the Commonwealth had begun the sort of gunboat diplomacy that has characterized its foreign policy ever since: Albrennian merchants would establish themselves in remote corners of Marceaunia Minor, sell guns and buy sugar or bananas or rubber, and call in Fleet gunboats and Marine shore parties when local chiefs or caudillos attempted to back out of the deal. In order to protect these economic adventurers, the Fleet ballooned in size. It absorbed first its civilian superiors in the Department of the Navy, and then most of the budget of the Department of War, and it acquired unique legal privileges and protections as it went. By 1860, Albrennia's army had been reduced to a gendarme force of fewer than ten thousand men, but its navy was among the most powerful in the Western Hemisphere.

Albrennia also pursued an alliance with the Federal Republic of Amandine, which had emerged after the Continental War as the most powerful rival to Audonia in Marceaunia Minor. In the War of the Adrienne Sea (1865-1869), Albrennia's first major war as an independent state, Amand troops and Albrennian Marines seized Audonian forts and trading posts all over Maceaunia Minor, and the Amand Navy and Albrennian Fleet defeated the Audonian Navy. Though Audonia was never invaded, the war marked the end of its preeminence in the affairs of Marceaunia Minor, and its replacement by an Amand-Albrennian axis that lasted for the rest of the nineteenth century. It also so disrupted life in much of Marceaunia Minor that it sparked a wave of immigration from the continent to Albrennia, sharpening social tensions.

After the Treaty of Ste-Lourine, Amandine became the hegemon of Marceaunia Minor, but Albrennia replaced Audonia as the continent's greatest trading power. Albrennia's network of trading posts and "economic adventurers" evolved into a modern web of corporate subsidiaries, trading concessions, monopoly agreements, and anti-smuggling patrols across the Western Hemisphere and beyond. Between 1869 and 1874, politicians and journalists in the Commonwealth first began to speak of their "invisible empire": Albrennian companies bought up plantations and mines throughout Marceaunia Minor, and the Albrennian-Amand alliance ensured the Commonwealth a blind eye from Amandine when it used the Fleet to defend or expand those investments by violence. Economic imperialism, with its risks and riches, has been a consistent feature of Albrennian history ever since.

Pillarization and the Matthean System

Forty years of uninterrupted prosperity and growth came to an abrupt end with the Panic of 1876. A crash in the price of silver made it impossible for the Harp-Wellfleet Bank to redeem millions of guilders in bonds from the Bank of Albren, causing a cascading crisis of confidence in the credit of most big banks and, ultimately, in the value of the Commonwealth guilder itself. To force the crisis under control, the Bank of Albren ultimately switched entirely to a fiat money system, abandoning the silver standard altogether. Then it bailed out the banks with the new paper guilder, known widely as the "greyback." But this did not resolve the crisis: widespread doubt as to the greyback's true value put Albrennian companies abroad at a severe disadvantage against their economic competitors. The Commonwealth responded with fourteen small-scale military interventions in Marceaunia Minor between 1876 and 1880 - mostly shore bombardments and Marine incursions - against towns and companies that refused to accept payment in greybacks. The show of force succeeded: the Albrennian guilder became the first valuable currency in Levilion to be guaranteed not by specie but by the credit of a central bank alone.

The greyback may not be backed by silver, but it is backed by lead.

— Chancellor John J. Heathering, 1879

By 1880, the worst of the economic depression was over, but the Albrennian economy had been changed beyond recognition. Hundreds of companies with origins going back to the sixteenth century were bankrupt. The few corporations that had survived bought up billions of guilders' worth of distressed assets, and many succeeded in consolidating an entire sector of the economy beneath their single corporate umbrella. Almost all shipbuilding - from the iron mines and the lumberyards, to the factories producing screws, to the shipyards themselves - became controlled by Wellfleet Industries. General Armaments had a similar top-to-bottom control of the arms industry. By 1882, the Albrennian economy was unprecedentedly centralized and vertically integrated, with just a dozen corporate conglomerates accounting for nearly three-quarters of GDP. These became known as the Pillars. They have dominated Albrennia's economy and politics ever since.

Pillarization enormously increased Albrennia's industrial efficiency: vertical integration reduced transaction costs at every stage of the manufacturing process, and permitted economies of scale that have allowed the Pillars to undercut foreign competitors ever since. But pillarization also created a de facto employer cartelization of the labor market: a small group of corporations, by deciding on a common compensation plan, were able to prevent wage competition across the entire economy. Albrennian workers, previously accustomed to a fairly high standard of living, suffered completely stagnant wages for almost twenty years. Widening economic inequality exacerbated preexisting social inequality, because the native-born, ethnic-Rythenean, mostly Rotiferist Establishment - educated primarily at Tolland and Alford Universities - controlled both the Pillars and the government. Tens of millions of non-Rythenean, Apostolic citizens - many of them immigrants from Tyrnica or Palia, or refugees from the conflicts in Marceaunia Minor - found themselves utterly excluded from economic and political power.

Working-class Albrennians turned to increasingly radical labor activism as the solution to their plight. Local union organizing drives were met with brutality by gendarmes and even Fleet Marines, but organizers tended to succeed anyway: repression only generated a greater pro-union backlash. As one workplace after another unionized, organized labor mirrored the vertical integration of the Pillars: all the unions in the shipbuilding industry federated into the United Brotherhood of Shipwrights, which represented Albrennian workers at every point along Wellfleet Industries' supply chain from the mine to the shipyard. Ultimately, these sectoral unions went one step further; they federated again, creating "one big union": the Albrennian Conference of Labor, or ACL. By 1898, more than seventy percent of Albrennian industrial and farm workers belonged to unions affiliated with the ACL, and there was open talk of syndicalist revolution in most major cities.

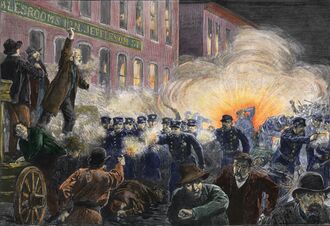

In July 1898, tensions boiled over after Fleet Marines gunned down strikers in Sherborn, and the ACL called a general strike. Chancellor Samuel Penry declared martial law, and gun battles between armed strikers and Fleet Marines ensued in several cities, leaving hundreds dead. But the strike successfully shut down the entire Albrennian economy for fifteen days - known in Albrennian labor circles to this day as the Glorious Fifteen. On the sixteenth day, the government capitulated: it recognized the unions, and called a conference of the Pillars and the ACL to discuss fundamental changes to Albrennia's economy and society.

The Providence Conference was chaired by Vice Chancellor Edwin Matthews. It seems to have been clear to all the participants that Albrennia was on the brink of civil war; in avoiding that fate, they painstakingly reached a compromise that fundamentally altered Albrennia's government and economy. That compromise became known (after Matthews) as the Matthean System. It created a new entrance exam on which all university admissions would be based, and it made all universities, including Tolland and Alford, tuition-free: these reforms substantially democratized access to Albrennia's powerful Establishment. But the Conference also allowed the Pillars to retain their unofficial sectoral monopolies, refusing to adopt any antitrust laws that would break them up.

Far more importantly, the Providence Conference recognized the sectoral unions that represented each Pillar's employees, and made union membership compulsory in order for a worker to be hired in any given sector of the economy. Each sector of the economy was thus defined by a single corporate conglomerate and a single labor union, to which all of that Pillar's workers belonged. Every three years, the government would mediate between all of the Pillars and the ACL as a whole, and the results of those negotiations would become law: setting the minimum wage, pensions, healthcare benefits, and unemployment insurance that every employer would have to pay to every worker. Albrennia's welfare state would be paid for directly out of corporate profits, not tax revenue; and it would reflect the result of corporatist bargaining, not legislation. That paradigm shift defines the Matthean System, and it has been the foundation of Albrennia's political economy ever since.

The system has worked fairly well in the 122 years since the Providence Conference, and in the first decades after 1898, it was overwhelmingly successful. The Pillars adjusted to sharply increased labor costs by relying on the unions to improve the skill of workers, which increased per-worker efficiency and boosted overall production. This symbiosis of labor and management was most successful in the arms industry, which in five years made General Armaments the world's largest private arms dealer, but it contributed to a rise in productivity in every Pillar. Albrennia entered the twentieth century as a rising economic power on the world stage.

The Great Wars and the Invisible Empire

General Armaments found a profitable market for its products in the Aillacan-Rocian Union, where Albrennia's "invisible empire" received its greatest setback. Albrennia first backed a coup by the Union's vice president, in hopes of protecting the Pillars' economic interests. This unleashed such dramatic political unrest that in 1904 the Commonwealth was obliged to back a second coup, this time by the Union's landed elite. The new government proved incompetent: it promptly declared war on Amandine, and despite repeated arms deals with Albrennia, it suffered several devastating defeats. The Union military then seized power, expelling and nationalizing Albrennian corporate holdings in the process. By the time peace returned, the Aillacan-Rocian Union had collapsed into civil war, and the Lacasine Republic of Aiyaca had been born: an implacably left-wing polity that has been a frequent foe of Albrennian influence ever since. Moreover, Albrennia had sacrificed its alliance with Amandine, because it had supported the Union government's war with that country. The "invisible empire" had suffered a severe blow.

But a much bigger arms market was opening up in Auressia, as that continent's arms race accelerated toward the outbreak of the First Great War in 1908. General Armaments and Wellfleet Industries sold hundreds of millions of guilders' worth of arms and warships to both the Coalition and the Galene League, and many Auressian historians would later blame Albrennian greed for the outbreak of war. When the war finally came, however, Albrennia immediately joined the Coalition: the Commonwealth's historical ties to Rythene remained powerfully culturally resonant for the Establishment, and the Establishment still controlled the Albrennian government. As the Albrennian Army had already withered into a gendarme force, no Albrennian ground troops were sent to Auressia; but for the second time in history, the Fleet sailed into the Galene Sea. Unlike in the War of the Commons, the Fleet was no longer a hastily assembled force of armed merchantmen; rather, it was product of one of the world's most powerful shipbuilding industries and strongest naval traditions. At the Battle of Evverkäben (1912), the Fleet failed to achieve outright victory, but it bloodied the Tyrnican Navy badly enough to force it into port. Thereafter, the Fleet imposed a crushing blockade that helped to starve Tyrnica out of the war. At the Treaty of Arden in 1914, Albrennia was seated as the equal of the other Coalition nations - an event still remembered today as the moment when Commonwealth became a world power.

In the postwar period, Albrennia was both an asset and a hindrance to Rythene's global dominance. The Albrennian Establishment still felt a deep loyalty to Rythenean culture and republican values, and so the Fleet was a willing partner to the Rythenean Navy in enforcing a vision of maritime law based on free trade and free navigation. By the late 1920s, Albrennia had actually gone further in this regard than Rythene: it was consistently advocating for a more forceful stance against Songha, and unsuccessfully attempted to assemble a coalition to stage a freedom-of-navigation operation through the Straits of Qes.

But Albrennia was in other ways a competitor to Rythene: while the older country remained a major imperial power, Albrennian companies quietly established themselves in Rythenean colonies and purchased lucrative local industries out from under the Rythenean administration. The Commonwealth's "invisible empire" spread across the world like a parasite on Auressia's colonial empires: a global network of corporate subsidiaries and private oilfields, in which the name on a contract mattered more than the flag that flew over a city. In Marceaunia Minor, Albrennia managed to reestablish its alliance with Amandine: both nations had ultimately joined the Coalition in the First Great War, while Audonia remained neutral, and so Albrennian diplomats used wartime public opinion to maneuver Amandine away from Audonia and back into alliance with the Commonwealth. With its southern flank thus secured, Albrennia was able to restore its influence in Rocia: supporting a succession of conservative and authoritarian regimes during Rocia's so-called Años congelados, and receiving control of lucrative mines and agricultural concessions in return. In 1919-20, the Fleet Intelligence Corps even helped the Aiyacan military to stage a coup and place Pablo Pardo in the presidential palace; for the next twenty-eight years, Pardo's regime secured Albrennian access to Aiyaca's cash crops and natural resources, and Albrennian weapons and cash kept Pardo in power. By the mid-1930s, Albrennia's "invisible empire" had reached its apex.

Problems were already apparent, though. Waxing Songhan influence in Amandine put pressure on the Amand-Albrennian alliance, since Albrennia remained committed to a hawkish line against Songhan expansion. After more than a decade of issuing lonely warnings about the Songhan threat, both the Albrennian government and the Albrennian public were eager to fight when the Second Great War broke out in 1937. Albrennia joined the Coalition, and the Fleet immediately sailed for Isuan. But after its victories against Tyrnica in the First Great War, the Albrennian military establishment suffered from crippling overconfidence, and it had difficulty working with its new Audonian allies. Alone, the Fleet sought battle with the Songhan Navy to defend the Ta-Puia Archipelago, and was forced to retreat - leaving eight thousand Fleet Marines marooned on the islands, where most of them would perish in battle or from mistreatment after capture. When the Fleet rallied to defend Blaykish Mesonesia, it was shattered again, losing four aircraft carriers and twelve thousand lives. The myth of Albrennian naval invincibility had been obliterated, and the Commonwealth's influence waned accordingly: in Rocia, a new liberal government managed to win election, and was able to negotiate a far more equal trade agreement with the distracted and weakened Albrennians.

Nevertheless, under the leadership of Chancellor Alfred Temple, Albrennia rallied. Late 1939 to early 1941 witnessed an unprecedented national mobilization: Wellfleet Industries ceased work on all civilian shipping, and managed to produce twelve aircraft carriers, thirty cruisers, and ninety destroyers in twenty months. To crew the new Fleet, Albrennia instituted its first - and thus far only - national draft. The Albrennian admiralty finally learned to work with its Audonian counterpart, and Amandine belatedly joined the Coalition, bringing with it priceless intelligence about Songhan naval movements. In July 1941, acting on Amand intelligence and supported by the Audonian Navy, the Fleet intercepted and practically annihilated a Songhan invasion armada at the Battle of Saint-Baptiste: establishing Allied control of the eastern Demontean and paving the way for Amandine to liberate Blaykish Mesonesia. The next year, Amandine, Audonian, and Blaykish troops seized the southern peninsula of the Qes Straits Zone, and the Fleet used this opening to force a path through the straits: fighting one of the largest naval battles in history, and damaging the Songhan Navy beyond repair. By the end of the war, the Fleet was the single largest force in the Sea of Qes. While Albrennia had not fought on land since the debacle of Ta-Puia, and while it had not contributed in the Auressian Theater at all, its naval might had been crucial to the outcome of the war in the Demontean.