User:Tranvea/Sandbox Misc

| Normalisation Modernisation and Harmony Campaign | |

|---|---|

| Part of Zorasani Unification, Rahelian War, Irvadistan War | |

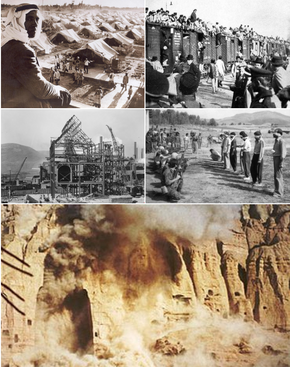

From top-left clockwise: A resettlement camp in Khazestan (1956); Togotis being transported by train to Lake Zindarud; Rahelian tribal leaders before a firing squad (1979); the destruction of the Great Zohist Monument in southern Pardaran (1982); Construction of one of many factories in new industrial cities | |

| Location | Union of Khazestan and Pardaran, Zorasan |

| Date | 1951-1988 |

| Target | Political opponents, Gâvmêšân, ethnic minorities, and occupied territory citizens |

Attack type | population transfer, ethnic cleansing, forced labor, genocide, classicide, |

| Deaths | 980,000-3,980,000 |

| Perpetrators | Zorasani Revolutionary Army, UCF |

| Motive | Modernisation, industrialisation, urbanisation and internal stability |

The Modernisation and Harmony Campaign (Pasdani: کرزیر نوژزه و توفیق; Kârzâr-e Nojāze va Tavāfogh; Rahelian: حملة التحديث والانسجام; Ḥamlat Taḥdīṯ al-Insijām) was a thirty-seven year state campaign conducted between 1951 and 1988 by the Union of Khazestan and Pardaran, and its successor state, the Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics, aimed at stabilising and modernising the country. It ran from the beginning of Zorasani Unification and eight years after its completion, and involved the forced relocation of ethnic minorities, ethnic cleansing, cultural genocide, rapid industrialisation, urbanisation and classicide. Between 1950 and 1988, an estimated 16.4 million people were relocated from their homes to different regions of the country, of these, roughly 8.2 million were forced to live in new industrial cities and new agricultural lands, while numerous cultural norms and systems were dismantled, including Rahelian tribes, nomadism and the repression of minority religions. By its end, between 980,000-3,980,000 people were killed directly or indirectly during the campaign, urbanisation rose from 15% to 64% by 1988 and Zorasan emerged as one of the most industrialised countries in Coius.

The Modernity and Harmony Campaign was devised by the government of Mahrdad Ali Sattari during the late stages of the Pardarian Civil War as a means of rapidly modernising the nation, to prevent the return of the colonial powers and to provide the state with the economic and industrial base from which it could militarily achieve unification. Sattari and his inner-circle identified a variety of "obstinate elements" of Zorasani society and culture that held the nation back from modernising into an economic and political powerhouse, this included certain ethnic minorities, the Rahelian tribal system, Steppe nomadism, wealthy landowners and their political opponents. The ruling ideology Sattarism, included a focus upon what it termed "modernity" (Ḥadāṯa), this was an all-encompassing term denoting the necessary adoption of technology, science and industry as well as the corresponding social changes needed to achieve "modernity." Sattarism also blamed these "obstinate elements" for the Etrurian conquest of Zorasan and Euclean domination, and would need to be destroyed to avoid a repeat. The targetting of ethnic and religious minorities for relocation was justified under claims that these "strategically placed peoples" would be most resilient to unification and adoption of a unifying Zorasani culture and indentity, therefore their homelands or areas of concentration would need to be broken up. The primary targets for relocation were Togotis, Kexri, Chanwans, Yesienians and adherents of Badi, in most cases hundreds of thousands were displaced and their former homes resettled by either Pardarians or Rahelians as a means of diminishing their concentration within geographical areas. Those displaced were re-setteled thousands of kilometres away, in either pre-built housing districts around new agricultural lands or industrial cities, or in some cases, forced to construct their homes from scratch in isolated areas. From 1958 to 1981, the campaign targetted perceived enemies of both the state and the campaign itself, who the government dubbed Gâvmêšân (Pasdani for Buffalo, in apparent reference to their "stubborness"), this group included tribal leaders, critics of the Sattarist state, socialists, wealthy peasants and shepards, monarchists and those related to the Pardarian, Khazi and the northern Rahelian royal families; the latter targeted mostly during the Rahelian War.

The campaign began to drawdown by 1985 and was officially dissolved in 1988 by order of the Central Command Council, which proclaimed the Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics, "unified, stabilised and introduced to social harmony." While the campaign delivered rapid urbanisation, industrialisation and modern technologies, it also significantly disrupted the lives of millions, who were evicted and transported away from their communities or places of birth. The attacks on cultural uniqueness of the various minorities has led many to accuse the campaign to have engaged in cultural genocide, while the cost in lives from both direct violence and indirectly through resettlement has led others to describe a viable case of ethnic cleansing and genocide. The replacement of resetteled minorities by Pardarians and Rahelians also draws much continued condemnation. Today, it is a criminal offence in Zorasan to refer to the campaign as a crime against humanity.

Background

Sattarism and Modernity

The overriding origin of the entire campaign was the ideological influence of National Renovationism. Developed during the Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command’s period of exile in northern Shangea, it adopted what Akbar Salami describes as the “Cult of Science and Industry”, which in turn was conceptualised as “Hadatha” (حداثة) – a Rahelian word meaning ‘newness’ or ‘modernity.’ Hadatha and its ‘Cult of Science and Industry’ would encapsulate the National Renovationist view that the more industrialised and technologically advanced a country was, the more powerful it was compared to others. Modernity, therefore, was written as a reaction to the Etrurian conquest of Zorasan – Etruria was more industrialised and advanced compared to the Gorsanid Empire, which in turn was condemned as backward, sentimental and too de-centralised to confront or defeat the encroaching colonial powers. If Pardaran, and later Zorasan, was to survive a return of colonialism, it would need to rapidly industrialise and modernise to reduce the gap in national power. From Modernity or Hadatha, would spring forth all subsequent actions and plans of the Campaign, including the eradication of agrarian ways of life, nomadism, tribalism and in the extreme, select minorities deemed to be a threat to modernisation or societal cohesion.

Akbar Salami, a leading historian on the Campaign explains that the desire for modernity would require a complete transformation of society, from an agrarian one culturally and societally wedded to the soil, into an urban and industrial one. This he believes, explains the often-violent plans to eradicate cultural norms intrinsically linked to agrarian life.

Salami and other leading researchers have also argued that this transformative campaign was also envisioned as a means of establishing a new “modern society”, implementing Ettehâd and abolishing the “old divisions and sentimentalities” that condemn Zorasan to colonial rule. Through the transformation of society and its adoption of modernity, a collectivist, totalitarian society could be constructed in which the labour and activity of all citizens is dedicated to the greater good of the state and population, and a society in which the needs of the individual are sacrificed voluntarily.

The founding of the Union of Zorasan in 1952, also influenced thinking toward the Campaign, notably, Mahrdad Ali Sattari’s repeated fears of the vast oil and gas reserves held by both Pardaran and Khazestan – he feared this would further entice Euclean powers to return, but also with some degree foresight, feared a wilful dependence on petrochemicals for state finances. He described petrochemicals on numerous occasions as the “Black Opium”, and saw industrialisation as a means of averting both scenarios. The Black Opium moniker would define Zorasani economic policy for the next 70 years to this day.

Legacy of Euclean colonial rule

Beginning in the early 1820s, the Gorsanid Empire was slowly subjugated primarily by Etruria, this process initially began with the seizure of At-Turbah and Zibakenar in 1821 and 1822 respectively as a means of combating corsairs that attacked Etrurian shipping in Solarian Sea. Through these occupied ports, the Etrurians steadily forced open the Gorsanid Empire into one-sided trade agreements, ostensibly for Etruria to secure a monopoly on trade altogether. In 1839, the Etrurians occupied the Riyadhi Peninsula following a failed local uprising, this was followed in 1843 with the occupation of the entirety of Irvadistan in the First Etruro-Gorsanid War, as well as the cities of Chaboksar and Ashkezar. This led in 1849 to the near outbreak of war between Etruria and the Kingdom of Estmere over the formers efforts to achieve monopolisation, leading to the Treaty of Virgillia, which forcibly granted Estmere control over the Gorsanid port cities of Khusavar, Bandar-e Sattari and Bandar-e Daryush, in exchange, Etruria was granted rights over the remaining territory of the Gorsanid Empire. This culminated in the Second Etruro-Gorsanid War (1852-1858), which began with the assassination of Shah Akbar Reza II by his brother Fereydun Reza I, who then instigated a series of attacks on Etrurian-held territory. Vastly outmatched in terms of technology and military training, the Gorsanid Empire ultimately collapsed with the occupation of the entire empire under Etrurian rule, this was formalised in the 1860 General Solarian Ordinance, which divided the Empire into two Dominions of Cyracana and Rahelia Etruriana, and two Protectorate-Generals Ninavina and the rump Pardarian monarchy, the Sublime State of Pardaran under the Zarafshan dynasty. As Protectorate-General, the Sublime State would provide Etruria with exclusive trade access and submit to total Etrurian control over its resource development, infrastructure, defence and foreign policies, while retaining control over several internal affairs.

From 1860 to 1941, there was little in the way of difference between how Etrurian approached the economies of both its Dominions and Protectorate-Generals, a reality that would be consistent under both the monarchy and Second Republic, though the political realities would differ considerably over time. Etruria unlike its peer colonial powers did not engage in settler colonialism, rather that sought solely to militarise its colonies and focus on resource exploitation and development. Though they found no discernable industry within the Gorsanid Empire by 1860, they did however, discover a vast territory of fertile farmland, thick and lucious forest and rainforest and deposits of coal, iron ore, copper, tin and gold. Petrochemical reserves would be discovered in the late 1930s, but the Solarian War would limit development to select fields off-shore and on-shore in Khazestan. As such, Etrurian colonialism was driven by the need to extract resources for processing and refinement in metropolitan Etruria, including foodstuffs, coal and iron ore which fuelled Etruria's industrial revolution. Overtime this would lead to great disparities between coastal Zorasan and the interior, with Etrurian development being near-exclusively focused on the port-cities and the infrastructure linking them to the resource rich interior and farming regions, while simaltaneously, maintaining the agrarian-centric way of life found prior to the conquest. Furthermore, the Etrurians only mechanised cash crop estates to boost producitivty, leaving many staple crops farmed in ways unchanged for centuries.