Benaajab

Enlightened Shahdom of Benaajab নদীপথ আলোকিত রাজ্য Nadīpatha ālōkita rājya | |

|---|---|

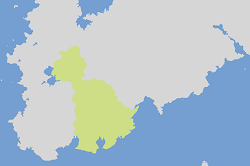

Location in Ochran | |

| Capital | Rangpur |

| Official languages | Bangla |

| Ethnic groups (2015) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Benaajabi |

| Government | Unitary Constitutional Monarchy |

• Monarch | Aarul Bogra |

• Prime Minister | Modanatha Praśasta |

• Supreme Susurrant | N'yāẏaparāẏaṇatā X |

• Minister of Labor | Vyasa Gautama |

• Senior Magnate | Napti Baltacha |

| Independent | |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | 93,541,968 |

• 2010 census | 89,351,435 |

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate |

• Total | 426.551 billion |

• Per capita | 4,560 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2015 estimate |

• Total | 164.072 billion |

• Per capita | 1,754 |

| Gini (2010) | medium |

| HDI (2015) | medium |

| Currency | Bong (ƀ) |

Benaajab (Bangla: নদীরপথ, Nadīpatha, lit. path of the rivers), officially the Enlightened Shahdom of Benaajab is a constitutional monarchy in South Ochran on the northern coast of the Vespanian Sea. The Shahdom is bordered by Iotopha to the west, Uluujol to the north, and Jhengtsang to the east. The country is mostly composed of highlands and ridges with the population concentrated around a the Mehdinpur River, Lake Dhaka, and the southern coast. The Jāti, who speak the official Bangla language, make up 83% of the population with minorities of Kards, Sangma, and Mutul. Most of Benaajab’s 93 million inhabitants follow the Sādhanā faith and its various sects are presented prominently in Benaajab’s national and local governments. Benaajab is a developing economy with large investments in textile production and other manufacturing, but growth has been significantly hampered by state capital controls and resistance to foreign investment.

The first inhabitants of Benaajab were the sea-going Sangma, but most of the country was populated by the Kardish diaspora in the 13th century. Smaller states were absorbed by the Guatamid Empire, which successfully incorporated religious and political elements of Sadhana into its administrative structure. While the concept of the Gautamid monarchy endured for some time, the administration of the empire was ultimately lost as states became more independent. During the 10th century, Benaajab came under the sway of the Bayarid Empire and remained under the influence of its successors until the economic and political reforms, brought about by the Mutulese, brought the religious elements of Benaajabi politics to the forefront. In the late 19th century, the Mutulese withdrew from Benaajab and the modern Shahdom was formed.

Benaajab is the home of Sadhana, a diverse group of spiritual schools based on the collected teachings of reincarnated leaders. While there is no administrative center for the religion, nor a common religious hierarchy, millions of the faithful flock to the many sites of spiritual importance in Benaajab every year. The nation's reliance on clerics for political leadership, while it has maintained many great cultural sites and traditions, has also significantly hampered social liberalization. Strict social castes, the oppression of unfriendly religious identities, and racism has persisted in Benaajabi law and society.

History

Main article: History of Benajaab

The first civilizations in Benaajab were in the Djadasthana region where the ancient Mid-Lacustrine city states were constructed by the progenitors of modern Kards. Later, during the Tenghu expansion, many of these cities were abandoned creating a great diaspora of Kards, which formed the basis of many later civilizations. The Kardish diaspora displaced other cultures, such as the Dravidian Sangma peoples, who are now a prominent minority in the Kumrasthana region.

In first century BCE, a unified nation was formed under the radical ascetic Praśansanīẏa of Santosa. Praśansanīẏa, who founded the Guatamid Dynasty, forced the many temples of Benaajab to bend to his will in a campaign of subterfuge and violence. The Guatamid Empire reached its peak quickly and slowly declined as its resources were drained away by wars with the Buminids and the rising Latin Empire. After the death of the last Guatamid Emperor, Benaajab would not be reunified until the modern era.

During the expeditions of Akutze Selenecha, Benaajab was contacted by the Oxidentalese who established trading ports and enclaves in the large coastal cities. Indigo, especially, was of interest to the Mutulese who quickly grew in number and prominence as they sold firearms and other machined goods to the native aristocrats. Several noble houses went bankrupt stockpiling goods from Mutul which, though rare when first introduced, quickly lost their value as the volume of Trans-Makrian trade increased. In order to settle debts, great families were sometimes forced to surrender their karēra, their right to collect taxes. The K'uhul Ajaw sent colonial ministers to administrate the collection of taxes and to broaden the Mutulese trade network with the establishment of inland trade posts, roads, and other infrastructure. The Zhuz monarchs ultimately fell under the sway of these powerful governors and, after an unsuccessful and violent attempt to expel the Mutulese, de jure power was officially passed to a Mutulese governor.

During the 2nd Bandhaśēka Rebellion (lit. shake off), facing rising internal turmoil and a renewed sense of Benaajabi nationalism, the governor took steps to reinstate friendly nobles and priests into directly administered regions to sooth the locals. The devolution of powers proved to be a limited success as Great Houses and Monasteries offered a semblance of home rule. Mutul was, however, facing international criticism for the state of their colonies in Benaajab as well as internal criticism from the recently appointed Benaajabi intermediaries. These issues were brought to a head when the prince of indigo suddenly fell due to a change in popular fashion in Belisarian courts that quickly spread to the rest of the Romantic world. Large swaths of the country were unable to feed themselves and starvation riots swept the country. The governor was faced with an ultimatum from the Great Houses; independence or rebellion on a scale not seen before. Already bleeding money from the cost of maintain the local aristocracy and the falling prices of many of the goods produced in Benaajab, the K'uhul Ajaw permitted the governor to create a transitional committee of Mutulese and Benaajabis to appoint a monarch and hand over power.

Geography

Benaajab is located on the southwestern peninsula of Ochran on the southern border of Uluujol, the eastern border of Jhengtsang, and sharing a maritime border with Iotopha to the west. Most of the major settlements are built along Benaajab’s famous four rivers: the Medinipur and Dhansiri rivers in the central valley; the Bhagirathi River in the Kasthana region; and the southern Kangsabati River. Medinipur and Dhansiri, the Middle Twins, are a part of the greater Dhaka River Basin that feeds into the eponymous northern lake. Bhagirathi and Kangsabati are both Exodhakan (outside the Dhaka’s encircling Himabatha Mountains and Grabarekha Ridge) and flow south into the Bay of Kaphijala.

Benaajab is also famous for its monsoon season from July to September during which the much warmer land creates a low pressure region centralized in Quatkebon and storms form regularly. These summer storms feed all of the major rivers and turn swaths of semi-arid and mountainous territory into lush, arable land. The storms normally start in Suchkosong after they are blown by prevailing winds off of the South Ochran Steppe, but slowly move across the nation until the early months of autumn when the storms change direction and move against the prevailing winds to irrigate Kasthana, though these storms are much less severe.

Administrative Geography

Benaajab is divided into the seventeen provinces of Kunangtana, Silkutha, Rodhaijo, Ora, Raykali, Suchkosong, Quatkebon, Kulongpanta, Abangtana, Ireng Segara, Rayjurang, Kurang Gereja, Gedthalay, Santosa, Kanca, Kerudung, and Jerukhom. Each province has a local government, though not every government is the same, and are often grouped both physically and politically into the Kasthana (southwest), Kumrasthana (southeast), Medinsthana (central), and Djadasthana (north) regions each of which represent a roughly equivalent share of the population.

Largest cities or towns in Benaajab

National surveryorship office estimates for 15 Dec 2002 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Administrative division | Pop. | Rank | Administrative division | Pop. | ||||

| 1 | Rangpur | Quatkebon | 1,467,585 | 11 | Rahki | Gedthalay | 232,724 | ||

| 2 | Kath | Kurang Gereja | 1,300,262 | 12 | Sabat | Kulongpanta | 231,242 | ||

| 3 | Kumar | Abangtana | 1,124,743 | 13 | Dhol | Kerudung | 199,068 | ||

| 4 | Santosa | Santosa | 693,056 | 14 | Liyo | Ireng Segara | 187,970 | ||

| 5 | Djad | Kunangtana | 677,386 | 15 | Atoswong | Ireng Segara | 172,742 | ||

| 6 | Ora | Ora | 617,608 | 16 | Nirapada | Gedthalay | 171,468 | ||

| 7 | Pimpare | Quatkebon | 506,263 | 17 | Lothdar | Rayjurango | 168,800 | ||

| 8 | Jodhor | Jerukhom | 402,473 | 18 | Pangolin | Kurang Gereja | 163,114 | ||

| 9 | Kanchal | Kanca | 365,445 | 19 | Surya | Suchkosong | 161,829 | ||

| 10 | Cand | Quatkebon | 244,940 | 20 | Bagana | Suchkosong | 147,823 | ||

Politics

Main article: Politics of Benaajab

While Benaajab is formally a monarchy, the many interlocking institutions have led some scholars to classify Benaajab as a Pluralist Oligarchy, other consider it essentially theonomist. The state is officially embodied and lead by the monarch, who has many technical and ceremonial duties related to his or her role, but unlike the constitutional or executive monarchies of the world, the Monarch of Benaajab acts more like a parliamentarian or speaker for the state. Related to the monarch are a variety of other institutions that combine to serve the public interest, the most important being the bicameral Houses of Law, also called the Benaajabi Parliament, from which most parts of the executive branch are appointed.

After holding an election, normally once every five years, the majority party leader is invited to form the Inner Court, which houses the cabinet, and the minority parties are invited to form the inner assembly, a shadow cabinet with some unique duties. While the Inner Court is allowed to oversee the legislative branch of government and to maintain much of the civil service, it is not the exclusive executive. A member of the Conclave of Workers, normally either the Speaker of the Conclave or a senior member of the Conclave with an affiliation to the majority party, joins the Inner Court as Minister of Labor and must consult with the cabinet on his or her policies. Likewise excluded from direct legislative oversight is the Gilt House, which oversees monetary policy and the state’s large, directive capital apparatus.

Finally, a religious monarch, the Supreme Susurrant oversees most of the judiciary as well as acting as a final arbiter of disputes. The Supreme Susurrant offers binding advice to those who seek it and also invites public figures to consultations, which are less binding due to the ability of the consultee to refuse to attend. The Supreme Susurrant is also nominally responsible for the Conclave of Teachers, the state religious organization which has the power to appoint many of the most important figures of state. As a result of this important ad hoc authority of the Supreme Susurrant, the Monarch traditionally defers his or her status as first in the order of precedence.

Economy

With a nominal GDP per capita of $1,734 and a 13% extreme poverty rate (those living on less than $2 per day), Benaajab is the poorest nation in Ajax. Conditions have steadily improved since the 1970s when over 80% of the population lived in extreme poverty and the government plans to eliminate extreme poverty by 2050. Benaajab’s recent growth is related to export-focused industrialization and government-backed capital projects. While it is growing, 20% of Benaajab’s GDP is still made up of agriculture, which also employs 50% of the workforce. The nation is the second largest producer of rice, after Tsurushima. The fastest growing and largest industry sector is ready-made garments, other textiles and apparel are also extremely important.

The government’s Gilt House and Monetary Courts control most of the capital in Benaajab, though there is some foreign financial presence in the industrial sector. Xenophobic financial regulations and usury-control laws hamper Benaajab’s ability to grow, both of which are important pieces of post-colonial politics and the entire monetary government. Organizations such as the Four Rising Nations Summit’s BIMM Bank are critical of these laws and constantly seek to give Benaajabis access to more capital.

Culture

Religion

Main article: Sadhana

Sadhana (Bangla: সাধনা, lit. the pursuit), also known as the Path and the Pursuit, is the primary faith of the Jati people and is shared by 79% of the believing population of Benaajab, with an additional 13% following a related Zensunni faith. Sadhana encompasses many philosophical and mythic elements of Benaajabi culture and there is no single corpus of beliefs or texts followed by all of the denominations called “Schools.” Sadhana first appeared in the 4th century BCE and spread quickly across Ochran, changing to adopt many local customs and beliefs.

Some common elements of Sadhana are the veneration of a particular teacher, often Kakusandha Buddha or Mesfin Buddha, whose teachings are carried in an oral tradition by a dedicated group of teachers, monks, or ascetics. Most schools establish monasteries with the support of local nobles where they can pursue the path and minister to the locals, but some schools are entirely itinerant. Common elements include meditation, observing moral codes, reading sacred texts, foregoing material indulgence, and going on pilgrimages.

Aristocracy

Main Article: Nobility in Benaajab

The extant aristocracy of Benaajab acts as an important arm of the government, mediating the needs of the publicly elected legislature and the powerful clergy, which has recused itself from directly controlling policy. First and foremost, the nobles in Benaajab are officials of the welfare state appointed by the clergy. Other public functions include ceremonial duties and the recognition of merit in citizens through the state orders of merit.

The nobility is represented in the caste system as a part of the Niranjan caste, though they are officially forbidden from encouraging caste discrimination in their public functions.

Srama Castes

Main Article: Caste System in Benaajab

Srama (lit. labor) is the Dharmic system of labor, including unfree labor, in Benaajab and other Sadhanist states. Traditionally, Srama is the combination of three elements of society--Udyama (exertion), Gathana (materials), and Khadya (sustenance)--under the direction of a Dharmic aristocrat to supply the needs of the local community and the greater community of mankind. Since local aristocrats were often beholden to a superior bureaucrat, they were under pressure to use up all of their local labor and goods to prevent it from being taken away and used elsewhere in the dominion. This led to the often wasteful practices of building enormous palaces, throwing elaborate feasts for the peasantry, and undertaking the construction of great temples.

Because of the influences of Dharmic philosophy on the aristocratic tradition of the Jati, the Niranjan (pure) Caste has always had an awkward relationship with property. Arable land was considered the exclusive domain of the Khadya, the farmers, forages, and herders. All of the produce not directly consumed by the producer had to be turned over to the local Niranjan. Since produce of the earth and of beasts could not be owned, the Niranjan had to give it away or use it himself. The principal recipients of the gifts of the Niranjan are the Gathana trading caste and local temples (also considered Niranjan). Because of the reciprocal nature of the gifting relationship, the Niranjan are often difficult to displace, even though they are all appointed at the pleasure of high courts and, ultimately, the monarch.