Agriculture in Menghe

Agriculture in Menghe has today achieved very high levels of productivity in yield per hectare, and produces enough staple crops for Menghe to be a net exporter. The main crops are rice and wheat, but also include tea, cotton, sorghum, oats, potatoes, soybeans, and sesame seeds. Due to the growth of the industrial economy, agricultural products today account for less than 10 percent of national GDP, but the agricultural sector remains highly productive and Menghe produces more food than it consumes, allowing for a net export in agricultural products.

Geography

Climate

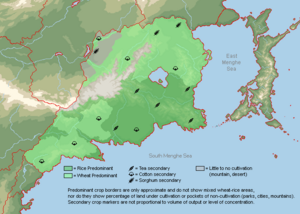

Agriculture in Menghe is shaped by the country’s varying climate patterns and soil quality. The Southern Plain, the Jijunghae Basin, and to a lesser extent the North Donghae Basin are relatively flat and lend themselves easily to grassland agriculture and horizontal irrigation systems. Other areas, such as the southeast, northeast, and central belt are strung with mountain ranges, though extensive terracing has historically expanded cultivation in some of these areas. The northwestern area is characterized by cool steppe and desert-like conditions, and has sand or poor-quality soil, though irrigation systems branching off of its rivers supply some agricultural land.

The southeastern area of the country, with a humid subtropical climate, receives heavy rain in both the summer and the winter and remains above freezing year-round, and since ancient times farms in this area have been able to produce two harvests per year. The Southern Plain, by contrast, is highly dependent on the summer monsoon rains, and during an El Niño cycle shifting rainfall patterns can produce devastating droughts in this area. Rainfall is more consistent in the northeast, which receives slightly more precipitation in the winter than the summer, but freezing winter temperatures limit the length of the growing season.

Historically, these soil and climate patterns have historically led to a clear geographic distribution of crop patterns. The southeastern band from the Chŏnsan mountains to Ryonggyŏng, which receives relatively heavy rainfall and warm temperatures throughout the year, has long been known as the "rice belt" because its conditions favor the construction of irrigated paddy fields and allow a second harvest in the winter. The areas north of this belt tend to specialize in wheat as the main staple crop, while the southern plain grows a mix of wheat and rice depending on farms' proximity to rivers and major irrigation projects.

Land use

| Land Area* | Arable Land | Permanent Crops | Under Cultivation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 3,427,592.87 km2 | 557,061.29 km2 | 64,027.46 km2 | 621,088.75 km2 |

| Percent | 100% | 16.25% | 1.87% | 18.12% |

| Hectares per Capita | 0.653 | 0.106 | 0.012 | 0.118 |

*Excluding territory covered by water.

The concentration of arable land varies across the country, and is highest on the Southern Plain and around the Jijunghae Basin but lowest in the Western Desert, with intermediate patches of terraced land in mountain valleys along the eastern coast. The total has declined slightly in recent years, caught in a "triple vice" by the exhaustion of soil, the depletion of groundwater, and the expansion of urban areas.

History

Archaeological evidence suggests that the first controlled cultivation in Menghe began around 7000 BCE, though it did not become widespread until around 2150 BCE. Cultivation developed most strongly in the central and southwestern river valleys, particularly the areas that today form Gangwŏn and Haenam Provinces. Blessed with favorable temperature and rainfall, these areas embraced rice as their main staple crop, favoring it over the less labor-intensive millet. By the 7th century BCE, farms in these areas were already using beasts of burden and cast-iron plows, and in the centuries that followed farms around Lake Jijunghae began to develop more sophisticated irrigation systems.

Due to its significance for the country’s future development, early agriculture features prominently in Sindo mythology, which teaches that the Yellow Emperor learned it from the earth god Hwangsin and subsequently passed it on to the people of his kingdom. Many villages today include Sindo shrines to gods associated with rain, farming, and irrigation.

Imperial Menghe

In order to feed their growing population and supply its armies, kings of the State of Yang (4th century BCE) ordered the construction of major engineering projects efforts to control flood-prone rivers and dig irrigation canals. These practices soon spread to the Haenam area, home of the rising Meng Dynasty. Subsequent dynasties invested in even larger projects, including transportation canals linking the country’s rivers. Many of the larger canals, such as the Grand Gangwŏn Canal, are still in use today, though usually after several rounds of expansion and reconstruction over the centuries.

Alongside the major projects were a number of smaller agricultural innovations, including the chain pump for irrigating fields uphill and the trip-hammer for pounding rice and grain. By the Sung Dynasty (938-1253) there was another revolution in water engineering for agriculture, driven by the invention and spread of waterwheels and mills. Extensive terracing also allowed farmers to cultivate otherwise marginal hillside areas.

Imperial Menghe canal projects not only extended the area under irrigation, but also allowed merchants to cheaply transport large amounts of grain and other goods more cheaply than mule trains would allow. Connections between “inward-flowing” (i.e., flowing to Jijunghae) and "outward-flowing" rivers were particularly important. With the help of canal transportation and centralized famine relief programs, Menghe under the Sung and Yi Dynasties was able to support multiple cities with populations of over one million, according to some of the higher historical estimates.

A persistent problem in Imperial Menghean agriculture was the consolidation of individual plots into landed estates. This was often accompanied by a rise in rural poverty among tenant farmers, who lacked an independent plot of land. Contemporary scholars, especially those with a background in the Yuhak school, criticized this practice as a source of injustice and associated it with dynastic decline.

Modern era

During the Three States Period (1865-1900), Menghe's factional governments supported a transition toward cash cropping for export, and invested in more modern production and transportation techniques. This gave rise to the commercialization and proletarianization of tenant labor, a process which continued after reunification. It also produced a class of large commercial landowners, who were close allies of the authoritarian government during the Greater Menghean Empire.

Following Menghe’s defeat in the Pan-Septentrion War, Allied occupation forces initially dismantled many of the large landed estates, but later revived them under new leadership in order to exert control over the country’s vast agrarian population. Cash crop production continued during this period, as the Republic of Menghe government followed foreign development advice by exporting cotton and tea in order to finance its reconstruction.

The rise of cash cropping and tenant labor during the 1950s and 1960s became a major source of rural unrest in the Republic of Menghe, especially given the fact that so many landowners were foreign or foreign-backed. This allowed the Menghean Liberation Army to build a strong rural support base by breaking up landed estates during its advance, under the slogan of "land to the tiller."

These small household plots survived into the 1960s, but in 1981 General-Secretary Ryŏ Ho-jun launched a collectivization campaign as a step toward full Communism. Rural land was divided into agricultural communes, which were further broken down into farming brigades and work teams. Combined with a severe El Niño cycle in 1985-1987, which brought drought to the southern and central plains, inefficient collective land management resulted in a severe famine that caused upwards of 10 million deaths.

Agricultural reforms

Shortly after the Decembrist Revolution, Menghe's new government implemented a series of reforms to stabilize the agricultural sector and address food shortages. In February 1988, the Interim Council for National Restoration issued the Emergency Guideline on Agricultural Contracting, which authorized county-level governments to organize village committees which would divide collective land into separate plots farmed year-round by individual households. Formally speaking, the land was still owned by the state, but these household plots functioned like small private farms and performed markedly better than collective plots. Choe Sŭng-min played only a modest role in the drafting of the Emergency Guideline, and did not see it as a permanent measure, but he greatly improved his rural support by claiming credit for decollectivization.

Still concerned about Menghe's millennia-long struggle to control the power of rural landlords, the Menghean Socialist Party imposed strict limits on agricultural privatization. When the National Assembly passed a formal law on rural contracting, it reiterated the previous provisional statement that all land is ultimately owned by county-level governments and only leased by farmers. The new agricultural law also imposed strict limits on the amount of land which each household could own, though the size of that limit varied by province and would increase with later reforms.

Another flurry of reforms came in 2005, in the aftermath of the Ummayan Civil War. Maverica and Innominada, both major agricultural economies, had intervened on the opposing side of the conflict and imposed sanctions on Menghe. In order to boost production, the Menghean government abolished the dual price system, allowing individual farmers to sell their goods directly to the market rather than through state distributors. The government also began an organized campaign to increase agricultural productivity on existing plots through investments in fertilizer, irrigation, and genetically modified seeds.

These reforms did not fully resolve the instability of rural land rights, but they did remove barriers to the buying and selling of leasing rights mid-term, prohibit the bulldozing of villages to transfer farmers into high-density apartments. Many Prefectural governments passed laws protecting "high-quality agricultural land" from encroachment by industrial zoning, which could instead be concentrated on marginal soil. In 2009 the National Assembly debated implementing land use quotas to keep the total area under cultivation from falling below 400,000 hectares, but it eventually rejected the idea on the basis that this would slow urban expansion and displace farms onto marginal soil.

Production

As a lasting result of decollectivization, most farming is carried out on smallholder plots leased from the local government but run as though privately owned by individual families. This results in relatively high yields per hectare of land, especially in the southeastern rice belt. It has also provided a source of stability for internal migrant workers, who can return to their family farms if they lose their industrial jobs. Many County and Prefectural governments have invested heavily in shifting these plots toward more intensive farming through greater investments in infrastructure and capital equipment.

Smallholder farming, however, does come at the cost of lower production per worker. As the Menghean economy has grown, the availability of work in the cities has pulled more and more workers away from the countryside. Members of the post-'90s generation also see agricultural work as undesirable and have left for higher-paying sectors, leading to a "graying of the countryside." In the early 2010s, the Ministry of Information and Statistics began to discuss the possibility of a rural labor shortage - an unprecedented development in Menghe's entire history.

After considering a range of proposals, the central government has responded by encouraging a gradual trend toward the consolidation of land plots into large farms with modern machinery. This has gone hand-in-hand with reform of the Household Registration System, which would allow rural families to more easily give up their land and move to the cities. Pilot projects for agricultural consolidation have been carried out in East and West Chŏllo Provinces and parts of Haenam Province, and the 2018 Law on Agricultural Consolidation substantially raised the ceiling on landholding while also streamlining the procedure for sale of land.

The table below shows official state figures on Menghean agricultural output for the top fifteen crops by volume in 2016, compared with harvests in the final years of the last two Five-Year Plans (2008 and 2013). All figures are reported in metric tonnes and are rounded to the nearest one thousand tonnes.

| Crop | 2008 output | 2013 output | 2016 output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | 73,886,000 | 84,146,000 | 88,134,000 |

| Rice | 84,450,000 | 91,287,000 | 96,249,000 |

| Cotton | 4,834,000 | 4,503,000 | 4,212,000 |

| Tea | 932,000 | 1,627,000 | 1,901,000 |

| Yuchae | 5,912,000 | 6,970,000 | 7,714,000 |

| Sugarcane | 31,304,000 | 36,869,000 | 41,679,000 |

| Fruit (all types) | 91,407,000 | 119,670,000 | 347,334,000 |

| Peanuts | 7,120,000 | 8,134,000 | 8,695,000 |

| Tobacco (flue-cured) | 835,000 | 885,000 | 858,000 |

| Beans | 8,322,000 | 7,209,000 | 7,334,000 |

| Tubers | 12,673,000 | 13,970,000 | 14,711,000 |

| Maize | 33,685,000 | 35,171,000 | 33,924,000 |

| Beetroots | 5,135,000 | 5,771,000 | 5,897,000 |

| Silkworm cocoons | 579,000 | 591,000 | 587,000 |

| Sesame | 251,000 | 293,000 | 306,000 |

Major agricultural products

Staple crops

Since ancient times, Menghe has grown wheat and rice as its main staple crops, and it continues to do so today. Owing to geography, the latter is grown along the “rice belt” running from the Chŏnsan mountains to the central peninsula of Ryonggyŏng province and branching southward down the Rogang river. Here, the abundance of rainfall and irrigated water allows the use of flooded paddy fields, and in some areas allows farmers to collect two harvests per year.

The remaining areas predominantly grow wheat, which in Meng cuisine is used for both noodles and bread. Generally, areas just north of the rice belt plant grow winter wheat, while the south and far north grow spring wheat. Wheat is preferred in these areas because seasonal rainfall and distance from major rivers make it more difficult to irrigate paddy fields.

Other traditional staple crops include oats, millet, and sorghum, some of which are also used as animal feed. Western traders arriving from the 16th century onward introduced maize, today the country's fifth-largest crop type by volume, as well as sweet potatoes, white potatoes, and some species of fruit and vegetables. Due to the prevalence of cooking oil in Meng cuisine, the country grows many types of oilseed, including soybeans, sesame seeds, sunflower seeds, and yuchae. Fruit production has climbed especially sharply in the last two decades, driven by increasing demand among urban workers with higher incomes.

Cash crops

Cash crop production makes up a relatively small portion of agriculture in Menghe, in part due to the legacy of Communist rule, when large plantations were broken up into staple-crop communes. Sugarcane production was particularly low in this era, but climbed in the decades that followed, increasing by over 50% between 2005 and 2015 and surpassing maize as the country's fourth largest crop by volume. Menghe is also a significant producer of cotton, which supports its domestic textile industry, though cotton production has declined in recent years. Silk is also a significant textile product, if a low-volume one; sericulture was first developed in Menghe over four thousand years ago and it remains an important industry today.

By volume, tea is the country's 12th largest crop category, but proportional to world output Menghe is one of Septentrion's largest tea producers. The southeastern area of the country produces green tea, jasmine tea, Oryong tea, and black tea (known as “red tea” in Menghe). Within Septentrion it is the only significant cultivator of white tea, which is grown in Ronggyŏng province. Most of these teas are grown in the southeastern area of the country, and they are produced for both domestic consumption and international trade.

Livestock

Meat consumption was relatively low in Menghe during the 1980s and 1990s, but has steadily increased as incomes have risen. By 2014, per capita meat consumption had reached 54.4 kilograms per person, above the global average but below most developed economies. Menghe imports most of its beef and mutton, but these make up only 4% and 3% of the country's meat consumption, respectively. Pork is by far the largest source of meat, and accounts for 62% of this total, with poultry accounting for another 18%. Domestic production meets over 95% of demand for these meat types.

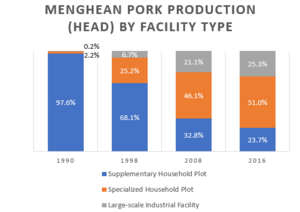

During the 1990s, the vast majority of Menghean pork and poultry production came from "backyard production," in which a household raises a small number of pigs or chickens as a supplement to its agricultural plot. As urban incomes rose, it became increasingly common for rural households to specialize in livestock production, and most of the increase in demand was met by an expansion in specialized household production and factory farms.

Organic agriculture

Recently, the Bureau of Agricultural Production encouraged local governments and small farmers to experiment with organic farming. The country has a Green Foods certification program to designate products grown without the use of pesticides, and it has worked to align its standards with international regulations on organic food. The Bureau of Agricultural Production sees a turn toward organic food as a way to reduce pesticide runoff and pesticide resistance, but has shown skepticism toward the program out of concern that organic food will be priced at higher levels above the reach of most citizens in the developing economy.

Peri-Urban Agriculture

The rapid expansion of urban areas from the 1990s onward has led to a rise in peri-urban agriculture. Although the practice began as a contingency measure, first as urbanites reacted to 1970s food shortages with urban gardens and then as Menghean cities grew to encompass the surrounding farms, metropolitan governments have recently worked to formally incorporate peri-urban agricultural land into urban economies. In addition to the often-cited benefits of increasing open space and providing opportunities for urban gardening, these plots require much lower transportation costs and have easy access to high-demand and often higher-income markets, making them optimal for perishable fruits and vegetables.

Aquaculture

As a supplement to its major fishing industry, which is in danger of depleting fish stocks in the South Menghe Sea, many local governments have invested in improving seafood production via aquaculture and mariculture. In addition to fish and shellfish, these facilities are also used to grow seaweed, a traditional delicacy in many parts of Menghe.

International trade

Self-sufficiency program

Throughout modern history, successive Menghean governments have considered it strategically important to maintain self-sufficiency in staple foods. This is especially true for the present government, which came to power in the wake of a severe famine. Plentiful arable land, a moderate population density, and high productivity per farm allowed Menghe to achieve self-sufficiency early on, and in 1998 the country exported more staple grains than it imported. Population growth averaged slightly under 1% over the last ten years, but as a result of the rising demand for meat and vegetables and the decline in arable land, the ratio of food production to food consumption did not rise considerably.

Current government statistics estimate that Menghe is able to produce 110% of the staple foods needed to meet the population's current consumption. Much of this production is concentrated in the main agricultural breadbaskets around the country, such as the Southern Plain. Emergency planners consider this level adequate to maintain healthy levels of consumption in the event of severe restrictions on food imports, though with Menghe's increasing integration into world trade, such a restriction has become increasingly unlikely.

Imports and exports

On average, Menghe is a net exporter of agricultural goods, though only by a small margin. Following the lowering of trade and regulation barriers, and especially the inauguration of the Trans-Hemithean Economics and Trade Association, Menghean agricultural goods have found large demand in Dayashina, which has a scarce supply of arable land relative to its population. Menghe is also the largest tea exporter in Septentrion, and its products can be found at oriental supermarkets around the world.

In many other areas, however, Menghe imports its food; much of the country's trade is bidirectional. Menghe is dependent on foreign producers for beef and most other large-livestock meats, including small quantities of horse meat from Dzhungestan. It also imports sugar from the Republic of Innominada, tropical fruits and spices from the southern hemisphere, and winter wheat and sorghum from Polvokia. After the growth of the domestic textile industry in the 1990s and 2000s, most Menghean cotton is processed at home and sold as clothing rather than being exported in raw bolts or bales, though as wages have risen in recent years many Menghean companies have sought to outsource their clothing production abroad where labor is cheaper.

Problems and challenges

Land rights

Although the reforms of 1988 through 1992 broke up the country’s agricultural communes, they did not actually replace them with formal private property. Instead, the original scheme piloted in Gangwŏn and Chŏnghae provinces involved giving individual households exclusive rights to cultivate and harvest a plot of state-owned communal land, usually for a period of one to three years, and sell crops above plan levels for a profit. Individual property rights remained unstable, because at the end of the lease (or even before it had ended) local governments could relocate a household to a different plot. This instability created disincentives to invest in long-term durable capital like greenhouses and piped irrigation, because the plot could be transferred to another owner before the investment had been paid off.

In response to growing complaints about this instability, in 1999 the Menghean central government extended household land leases to a duration of 20 years. These leases were formally held by a member of the household rather than the household itself, improving the quality of record keeping, and lessees could buy and sell rights to their plots in a form of controlled market, as long as the land remained designated for agricultural use. The central government also began a five-year campaign to construct a detailed cadastral survey of all household land, with the results centrally compiled by the Bureau of Land Use. Formal ownership of land was transferred upward from Town and Village to Prefectural governments, where personal disputes between farmers and government officials were less likely, and new regulations were put in place to improve land security.

Nevertheless, under the new policy land was still formally owned by the state, which retained the power to appropriate plots at will for a below-market fee and re-settle farmers elsewhere. County and Prefectural governments frequently used this power to buy up land at the outskirts of growing cities and towns, re-designate it for urban use, and then sell it to construction companies for a large profit. This practice became the source of widespread rural unrest during the 2000s and 2010s, often generating mass protests, public suicides, and other forms of resistance. Despite its original support base among rural farmers, the Menghean central government viewed “controlled confiscation” as an important way to fund local governments, keep development costs low, and control the expansion of urban areas, and it allowed the practice to continue.

Since 2014, some working groups in the NSCC have recommended working toward a system of formal private property rights in farmland, abolishing the practice of land confiscation and permitting farmers to buy and sell their plots at market values. Advocates of this reform have also defended it on the basis that it would control the expansion of small cities and large towns, which since around 2010 have reported a trend toward excess production in the construction industry. As of March 2017, the Supreme Council has suggested that it will begin pilot projects in land privatization in the near future with the eventual aim of gradually phasing in the new policy at the national level.

Agricultural employment

According to the most recent census, in 2015 there were 148 million people engaged in agriculture in Menghe, including children in agricultural households. This number amounts to about 28% of the overall population. This does represent a marked decline since 1990, when more than 65% of the population was engaged in agriculture, as economic growth has drawn migrants to cities and larger towns. Yet in absolute terms, it remains high by international standards, especially by comparison to other developed countries. Additionally, recent figures suggest that the agricultural population in many provinces is disproportionately older than the non-agricultural population, as people born after 1990 overwhelmingly report in surveys that they would prefer to work in the city.

In recent years, many prominent economists have argued that Menghe should begin transitioning from a labor-intensive, small-plot agricultural model to a model based on more dispersed landholding with higher worker productivity. This change would enable more people to shift to the urban labor force, where per-worker productivity is higher, and reduce the welfare and age imbalance between the cities and the countryside. Reforms in this area have been gradual, as further consolidation would require raising the land-ownership caps and changing the regulations around the transferrability of land; ideological resistance to large-landlord estates remains high in both the Menghean Socialist Party and the rural population. Government food security planners have also expressed concern that larger plots would produce lower yields per acre.

The Southern Plains provinces - namely, Hwangjŏn, East Chŏllo, and West Chŏllo - have gone furthest in encouraging land consolidation, as the flat terrain in these areas is amenable to large cereal plots with labor-saving mechanization. A particularly interesting innovation in these provinces is a provision allowing families who sell their land to move up the queue for Hojŏk registration in an urban area in the same province, allowing elderly farmers to move in with their children in the cities.

As of 2019, the provincial governments of Haesŏ, Goyang, and Chŏnghae are all drafting plans for reforms based on the Chŏllo model, and Haenam and the Daristan Semi-Autonomous Province are both in the early stages of encouraging large-plot consolidation. Farmers' views on the new policy are mixed, with some households relieved that they can sell their land and move to the city, and others complaining that their land is being bought up unfairly in the eager rush to roll out the process.

Environmental strain

During the decollectivization program, the central government encouraged local governments to retain some of the more marginal land in their plots under public ownership, and convert it back to forest or steppe land. This policy was particularly aimed at shoring up root cover on barren hillsides, which had suffered extensive deforestation during the expansion of communal land in the 1980s and were increasingly prone to soil loss and drought. As a result of this policy, the actual area of land under cultivation decreased between 1988 and 1995, even though overall yields were rising.

Some of this reclaimed wilderness was set aside in the form of nature reserves, particularly on forested hillsides on the periphery of cities, and remained protected from future encroachment (though illegal logging and poaching remained issues in some poorly enforced areas). Yet as more and more agricultural land was appropriated for urban use, displaced farmers were increasingly relocated to new plots, moving cultivation back onto marginal soil. This led to a rise in erosion, particularly in dry steppe areas along the semi-arid belt northwest of the central mountain range.

The increased intensity of cultivation also increased the use of water for irrigation, especially on expanded marginal areas. The threat to rivers and aquifers forced the national government to de-zone large areas of agricultural land as a means of reducing the burden on water use. At the same time, runoff from the increased use of pesticide and fertilizer, as well as illegal dumping by rural chemical facilities, polluted many important water sources, requiring new irrigation systems and sometimes forcing contaminated soil to be abandoned. Given the threat this poses to national agricultural self-sufficiency, central and provincial governments raised environmental standards around water pollution and dramatically stepped up enforcement after 2005, and by 2017 the situation has dramatically improved in coastal areas though it remains severe in certain areas of the interior.

Quality and safety

Like many developing countries, Menghe has relatively low sanitary standards for food production, and local governments’ emphasis on increasing production has led many to deliberately overlook violations under their jurisdiction. The rapid economic growth of the 1990s and 2000s and the relocation of factories further inland both increased water and soil pollution, with the Ministry of Environmental Protection estimating in 2009 that at least 5% of all national arable soil was contaminated by heavy metals and industrial residue.

The 2011 Yŏsu county chemical spill, in which the collapse of a tailings dam released mining waste into a river that fed large areas of paddy land, led to an especially pronounced turning point in environmental regulation. The central government organized a well-publicized response, laying off hundreds of involved public employees including the governor of Ryonggyŏng Province and sentencing the facility’s manager to death. After this show of force, the Ministry of Environmental Protection reported a sharp and sustained decrease in reports of agricultural contamination, though the Menghean Government in Exile claims that most of the decline is due to underreporting of actual damage.

The central government has also stepped up its standards of food safety, and there is widespread evidence that enforcement is becoming more consistent. But Menghean farms are still plagued by other safety issues, most notably the overuse of pesticides. During negotiations for the formation of THETA, Menghe agreed to take more aggressive steps to improve food safety regulations in return for lowered import barriers in Dayashina, and there are already signs that the use of pesticides and growth hormones has declined.