Distributed Engagement

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Distributed Engagement is the primary doctrine of the Army of Carthage. It promotes the employment of smaller brigade-sized formations with significant stockpiles of precision-guided munitions to improve the formation's lethality, while a robust communications network allows the rapid sharing of information between units to improve coordination and reaction speed.

Developed in the 1980s and adopted in the early 1990s, it has been updated regularly to account for trends in information technology and the development of networked systems. It replaced the previous "Guarded Crossroads" doctrine of the 1970s, which was largely discarded during the Northern War by commanders in the field as ineffective given the changes in warfare as well as Carthage's strategic constraints.

History

The Northern War of 1975 came at a time of great technological change in the Carthage Defense Forces. The development of the attack helicopter as well as faster, more mobile, and more powerful vehicles supported by increasing numbers of precision-guided munitions sparked a shift in priorities and strategic thinking. Technological superiority had contributed greatly to offsetting European superiority in numbers, but placed increasing emphasis on the technical training and individual skill needed to operate increasingly complex weapons systems and coordinate with faster and more mobile support assets. The development of these technologies required improvisation in the field by commanders to use these assets to greatest effect, as the necessities of war made the formulation and implementation of a new doctrine difficult given the length of time needed to fully develop a new system of organization.

Beginning in 1979, the Strategic Studies Institute at the Carthage Military Academy conducted a series of war games experimenting with various methods of organization, communication, and integration of supporting arms at differing levels. War experience indicated that the increasing tempo and lethality of warfare required decreased reaction times, pushing the level of independent maneuver and decision-making further down the chain of command. Further, it indicated that a quantity of smaller, more mobile, and more independent groups could effectively disrupt a concentrated enemy advance, as had happened during the Iberian campaign. The battlefield now also extended further into both allied and enemy lines as a result of increasing artillery ranges, increasing the burden on commanders now responsible for a larger area of operations.

Separately, Brigadier General Himilax Hanta of the Army Training Command released the results of his own study, "A History of Conflict," based largely on his experiences during the war as a brigade commander as well as analysis of numerous past conflicts stretching back to the Punic Wars. The study arrived at the conclusion that disrupting the enemy's decisionmaking process was a critical factor in warfare, and moreover one shared between forces large and small. This was believed to be the decisive factor in the victory of the more agile Carthaginian brigades over their larger but slower and less coordinated European foes.

The Army 1990 report released in 1986 presented a combination of Hanta and the institute's findings in a concept called "Independent Engagement," recommending a transition toward more independent brigade-level units, integration of artillery at the brigade level, increased spending on helicopters and combat aviation, precision-guided munitions, reconnaissance, and other supporting arms, and the formal adoption of a doctrine integrating these new arms at a more fundamental level. The report also stressed the importance of mobility and organization, the ability to retain both throughout the course of a future engagement, and the need to exploit these to disrupt the enemy's decisionmaking process.

At the time of its proposal, the doctrine attracted a host of critics both military and civilian over its requisite increases in soldier training and significantly increased capital costs. Many within the Defense Forces criticized what they felt was an over-reliance on emerging technologies and the longer training times and higher costs associated with fielding these weapon systems. Budget hawks within the legislature decried the expected expenditures, as the proposal sought to increase the adoption and use of technologically advanced weapons and coordination systems at great cost. As a result, adoption of the doctrine was delayed by several years until the signing of the Pretoria Agreement and a renewed period of increased defense spending made the proposal more viable in the minds of politicians and generals.

In 1991, Army command formally adopted the proposed reorganization following the confirmation of General Jabnit Chaikin as the new Chief of Staff. At the time, the new concept had been renamed Distributed Engagement following the refinement of the doctrine through further study. Despite the support of a growing faction of Northern and Pacific War veterans that had also supported Chaikin's appointment, full implementation of the proposed doctrine was delayed throughout the 1990s due to budgetary issues, program delays, political infighting in the legislature, and opposition within the Army on the grounds that the necessary supporting technology was not fully developed. Formal establishment and reorganization of infantry and armored units proceeded throughout the 1990s, but it was not until the mid-2000s that the proposed light cavalry units could be established due to the need to develop new vehicles and equipment.

In 2001 the doctrine was updated to the Revision 1 standard, updated to account for trends in improved networking capability and the exponentially falling size and cost of microprocessors. The new revision also called for the development of a "networked soldier" system, to improve communications integration at the lowest levels and introduce a wider array of technological aids, including night-vision and thermal sights. The Revision 2 standard in 2007 updated the doctrine to improve its focus on unmanned vehicles, including the introduction of UAVs into brigade reconnaissance squadrons, the divisional combat aviation brigade, as well as provisions for employment at even lower levels as part of an increased emphasis on surveillance and target acquisition capabilities. Revision 2 also addressed the integration of combat arms, moving this integration from the brigade to the battalion level.

Distributed Engagement

Carthage

Allied States

Ctesiphon Pact

Hostile States

European Liberation Treaty Organization (ELTO)

Asian Security Agreement (ASA)

Latin Security Framework (LSF)

Neutral

Axumite Kingdom

The role of the Distributed Engagement doctrine is to provide a framework for waging conventional war against the republic's expected enemies, in either offensive or defensive capacity. The three pillars of this doctrine are the principles of high lethality, rapid maneuver, and independent action, through which combat teams can remain continuously mobile in order to both conduct strikes on enemy positions as well as deny the enemy an opportune target for retaliation. Although focused on providing for conventional warfare scenarios, contingencies exist for nuclear warfare scenarios, although the republic currently holds a "no first use" policy in regards to weapons of mass destruction.

Under the Distributed Engagement theory, independent units of maneuver (brigades) are given significant freedom in their engagement of the enemy force once briefed on the overall objectives.

In addition to direct combat against expected European or Latin American forces, it is also expected that Carthaginian troops may be called upon to support allies both within and outside the Ctesiphon Pact. For this reason, rapid strategic deployability is a feature of the distributed engagement model, primarily centered on the creation of joint rapid deployment corps, combining air, land, and naval assets under a single unified command structure.

Strategic objectives

The primary strategic objectives of the Republic of Carthage are:

- Deterrence of possible aggression by remaining Montgomery Pact states

- Nuclear deterrent against strategic nuclear warfare

- Conventional deterrent via conventional military means

- Soft power deterrent via strong network of allies and economic superiority

- In the event of war, swiftly defeat possible aggressor states with minimal damage to domestic infrastructure

- Rapidly degrade the ability of hostile forces to maintain offensive combat operations

- Maintain the ability to conduct combat operations even under adverse strategic or tactical situations

- Support potential allies in future conflicts

- Maintain rapid deployment capability to respond to developing events as well as to demonstrate national will

- Maintain ground, sea, and air lines of communication with allied states

Strategic outlook

The development of the Distributed Engagement model and its priorities are largely a result of Carthage's political priorities. While Carthage maintains sufficient margins of superiority in manpower and materiel to deter rational actions by its hostile neighbors, strategic planners have assessed that the possibility of war against Carthage's Ctesiphon Pact allies is high, and that the republic must maintain a credible ability to reinforce and support its allies in order to maintain its political position. In addition, the deployment of this capability must not compromise Carthage's ability to defend its own territory or meet ongoing commitments in the international community.

As a result of these priorities, Carthage is aided and constrained by several major strategic features:

- While Carthage as a whole possesses great strategic depth, the dense population and number of major cities near the border with ELTO and ASA powers makes significant penetration by enemy forces a dangerous prospect due to the potential for significant civilian casualties and infrastructure damage.

- As a result, a high priority must be placed on defeating enemy incursions quickly before significant damage to civilian population centers can be incurred. In particular, damage to the Congo valley hydropower network must be avoided.

- Additionally, rapid counterattacks into enemy territory are also considered important, to place pressure on hostile governments and maintain at the very least strategic/diplomatic parity in terms of positioning.

- Carthage's two primary borders with hostile powers have vastly differing terrain, from the Pyrenees in Europe to the savanna and steppes of southern Africa. In addition, it is expected that threats to Carthaginian holdings in the Caribbean would also need to be addressed.

- All-weather operation and performance in multiple climates and terrain types is required of most equipment.

- Carthage maintains significant advantages in population size and total GDP compared to its potential opponents as well as at least parity levels of technology, but these advantages are not sufficient to completely nullify the potential for hostile forces to inflict significant damage on the economy.

- A large portion of the Defense Forces are stationed in the Overseas Territories, and is expected that such forces would not be able to respond quickly enough to reinforce the homeland in the event of war.

- The development and proliferation of precision-guided munitions as well as the rising cost and production time of modern weapons systems means that any potential war is likely to be short and decisive, with little opportunity to bring up deep reserves unless already mobilized before the outbreak of war.

Distributed Engagement was developed to address this outlook and the preceding strategic objectives by improving reaction times through the delegation of maneuver authority to the brigade level. Using a number of relatively independent brigades supported by divisional elements, the Distributed Engagement model is designed to disrupt enemy forces through rapid, unpredictable strikes before defeating the uncoordinated elements in detail. In addition, the same maneuverability and independence is postulated to make it more difficult for enemy forces to conduct similar strikes against Carthaginian formations.

Moreover, the Distributed Engagement model is designed to function regardless of force size, a significant benefit to expeditionary forces which may be outnumbered by their opponents. The previous Guarded Crossroads doctrine required a level of numerical parity and focused on defensive operations to slow and contain an enemy attack until other Ctsiphon Pact allies could become involved. The new doctrine discards this focus in favor of a more flexible system of engagement, wherein a greatly outnumbered force would rely more on disruption tactics before attempting any concluding battle, while a force with numerical superiority may engage in a concluding offensive more rapidly. In all cases, the primary objective is to maintain force cohesion while denying the enemy the same, and exploiting this disparity in organization to deliver crippling strikes with modern ordnance.

Operational objectives

At the operational level, the objective of Distributed Engagement is to disrupt the enemy's decisionmaking process, impeding the ability of the enemy force to maneuver and counter Carthaginian movements. Once so disrupted, the enemy formation becomes more vulnerable to defeat in detail through the rapid concentration of Carthaginian forces, or allows an outmatched friendly force to withdraw safely. As a result, Distributed Engagement places a high priority on targeting command and communications nodes in the rear areas while simultaneously protecting friendly assets against similar strikes.

Command disruption

Disruption of enemy command and communications network is a major goal of Distributed Engagement at the operational level, with the primary elements of this strategy being deep reconnaissance and detection assets such as airborne the RES-282 Shogun and RCS-290 Stentor electronic intelligence platforms and human intelligence in the form of special operations teams. Electronic warfare is also expected to be heavily utilized in order to degrade communications capabilities on the battlefield. Once located, command and communications assets are expected to be priority targets for strikes using any available guided munitions. This is termed "hard" degradation, as it directly impacts the enemy's command and communications structure as an independent system.

In addition to direct strikes against enemy command nodes, the doctrine places an emphasis on "soft" degradation of command capabilities through disruption of combat arms, including deep strikes against enemy forces in the rear, disruption of movements, and interdiction of supplies and support. Against a competent opponent well-versed in modern counterintelligence methods, finding and striking the opposing command network is expected to reveal many other targets of opportunity along the way, and strikes against rear-line non-command assets may exert a disrupting effect on the command network as officers must assess damage and the capability of their unit to continue combat operations.

Concepts and implementation

Force structure

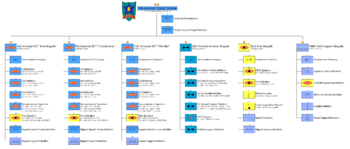

In order to allow commanders to keep up with the more rapid tempo of modern combat as well as the expanding battlefield, the primary unit of maneuver has been shifted downward from the division to the brigade, now reinforced with its own integrated supporting arms to form a brigade combat team. Each team is composed of several maneuver battalions supported by integrated fires, reconnaissance, and special troops battalions and capable of operating independently for up to 72 hours.

Since the adoption of the Revision 2 standard in 2007, brigades have been of standardized structure with a mix of vehicles and infantry at the battalion level, with ad hoc mixing occurring at the company level in the field. The objective of these reforms is to increase interoperability between units as well as create battalion and company teams of infantry and vehicles supported by lower level assets (such as mortars and support companies), in essence creating smaller combat teams in their own right.

Divisions are responsible for providing rotorcraft support, additional reconnaissance and intelligence assets, higher-level logistics support, high-level air and missile defense, and field hospital services to their brigades. Each has a field logistics brigade including engineering, logistics, electronic warfare, intelligence, medical, and electronic warfare assets, as well as a combat aviation brigade providing reconnaissance, transport, and attack support on call to brigade commanders. A fires brigade is also attached to provide long-range rocket and missile support to brigade operations. Divisions are still largely homogeneous in terms of brigade type, but the adoption of modular brigades allows easier transfer of combat assets between commands. The modularity allows ad hoc composite divisions to be created temporarily as needed, or brigades to be quickly switched between divisions.

Corps, army, and combatant command operations are limited mostly to operational direction, selection of specific objectives, and provision of even higher level logistical support including construction of more permanent infrastructure. In many cases, some if not all of these roles are taken on by the regional combat command coordinating all branches within a specific theater. If authorized, tactical nuclear support is coordinated at the corps level with possible delegation to the division level, but otherwise nuclear assets are maintained under the authority of central headquarters.

Brigade combat teams

The central formation of the Distributed Engagement model is the brigade combat team, centered on an infantry, cavalry, or armored brigade and reinforced with an integrated artillery battalion, battalion-strength reconnaissance squadron, and additional forward logistics support. Each brigade is composed of three maneuver battalions, including a mix of armor and infantry (for armor and cavalry battalions) or infantry and crew-served weapon support (for infantry battalions). Brigade strength ranges from ~3,800-~4,800 depending on type, and each of the three brigades is designed to fulfill different tactical roles while retaining at least some multimission capability. All brigades are fully motorized or mechanized, and some are tactically airmobile.

Armored brigade combat teams are designed to provide breakthrough firepower and high tactical mobility through their employment of large numbers of main battle tanks, currently the HTA-01 Rhinoceros and newer HTA-02 Jaguar II. Each BCT also includes a battalion-strength formation of mechanized infantry in IFVs dispersed throughout the three combined arms battalions, to provide timely infantry support while conducting operations. The primary combat strength of the armored BCT is its 132 tanks and 48 infantry fighting vehicles.

Light cavalry brigade combat teams are the newest type of BCT, designed around the new Iliad Medium Multipurpose Tracked Vehicle platform. The light cavalry BCT is designed to balance the protected firepower and mobility of an armored brigade with the strategic mobility of a lighter formation. Combat vehicles in light cavalry units are standardized on the MMTV platform in the ~30 tonne range, although with conventional support vehicles. Compared to armored brigades, light cavalry brigades have a 50/50 mix of armor and infantry, with two companies of each in every combined arms battalion, for a total of 108 light tanks and IFVs per brigade.

Infantry brigade combat teams provide more focused inclement terrain, urban fighting, and tactical air assault capabilities to the Army. Although classified as light infantry, infantry BCTs use light vehicles, particularly the WIL-41 Wallaby for tactical mobility unless employed in the air assault role. All infantry BCTs are trained for air assault, although the necessary helicopter support for full brigade air operations is generally provided only when needed except in dedicated airborne units. Certain infantry BCTs are also trained in parachute operations. Infantry BCTs are generally transported in the 180 WIL-41 tactical trucks used for brigade maneuvers, supported by an additional 60 WIL-42 weapons carriers.

In addition, a number of support brigades also exist. Each division typically has a support brigade of its own as well as a divisional fires brigade providing rocket artillery and long-range air defense support. The combat aviation brigade is also attached at this level, although helicopter support will typically be delegated by the division commander to brigade commanders who require it.

Battlespace

One of the important features of the original framework is the notion of the expanded battlespace in all dimensions. The current model presumes a total of five dimensions for commanders to consider: the three physical dimensions (height, depth, and width), plus time and information. The three physical dimensions define the physical area of responsibility each commander must keep watch over, while the last two abstract dimensions define how he must operate within those three dimensions to accomplish his objectives. All five have seen significant expansion at every level through the development and employment of new technologies.

The development of longer-range artillery and stand-off munitions has expanded the range in which a commander at any given level must be wary of attack or consider mounting his own. Units farther behind the enemy's front line are now of greater concern, while conversely a commander has a wider range of territory within which to station his own supporting arms. With increasing range comes also the expansion in frontage a given unit can be responsible for, expanding the battlefield in both width and depth. In addition, the vertical aspect of the battlefield has grown through the introduction of offensive air power in the form of attack helicopters and close air support craft through the 1990s, and the widespread employment of unmanned aerial vehicles in the following decades. The growing lethality of air-delivered munitions has also been accompanied by the growing use of aerial reconnaissance platforms, expanding not only the range but also the use of the vertical aspect.

Since the adoption of Revision 2, ongoing debate has considered whether even satellites could be considered a part of the vertical dimension, given their increasing importance and the development of satellite and anti-satellite weaponry. This controversy was somewhat addressed in the Revision 2 standard with the reclassification of "air power" to "aerospace power," but remains a point of contention, especially between Army and Air Forces senior commanders.

Time is related to depth as a means of assessing a commander's area of responsibility, with a given level of command having a certain amount of time to respond to battlefield conditions. This time is expected to increase at higher levels, as upper-level commanders with a larger area of responsibility must consider actions further in advance of those at lower levels. This applies to both friendly and enemy movements, with a corps commander responsible not only for directing the large buildup of his own forces for a potential offensive, but also monitoring the enemy positions for the same.

Information is the newest field to be classified as a primary dimension. While the three physical dimensions place physical boundaries on a commander's area of responsibility and time defines the speed and pace at which operations must be planned, information defines how a commander goes about making his decisions. In practice, this is collected from multiple sources, including reconnaissance elements within the commander's unit, intelligence provided from higher authorities, human intelligence provided by informants, and increasingly electronic intelligence from signals and electronic warfare units. Unlike the other four dimensions, there is no defined limit to a commander's area of responsibility in the information dimension, which requires sound judgment on the part of each commander to separate useful from unnecessary information and make decisions on an often imperfect tactical image.

Maneuverability

With the devolution of the maneuver role to the brigade, current brigade combat teams are expected to be strategically and tactically mobile independently of their divisional supply chains for at least 72 hours. This allows brigades to be rapidly deployed and immediately begin combat operations while additional support assets are being brought in or time for supply lines to be reestablished in the event of disruption by enemy forces without forcing a halt in brigade operations.

The operational objective of the brigade combat team is to use maneuverability and initiative to engage the enemy from a position of strength, while avoiding concentrated retaliation. Maintaining maneuverability requires both physical factors (timely engineering support, reliable vehicles, sufficient logistics), but also intelligence and signals factors to allow the unit to maximize the effect of its arsenal. In the current BCT model, this is reflected in the use of forward engineering units as well as dedicated reconnaissance squadrons in each brigade, supplemented by aviation assets at the division level. The widespread deployment of more advanced sensor platforms among line units is also designed to improve the surveillance and target acquisition capabilities of the brigade as a whole.

At the same time, a key objective is to deny the enemy the ability to effectively maneuver, through the employment of both physical means (minefields, harassing attacks) and intelligence means (deception, concealment, disruption of communications). In the case of the latter, both physical and electronic deception means are necessary, including electronic warfare and concentrated attacks on communications networks to disrupt the ability of the enemy to effectively coordinate his movements and leave him vulnerable to further attacks.

Role of technology

Under the premises of General Eustace Macdonald's 1996 theory, the primary roles of technology are to improve C4ISTAR functions and enhance lethality. Macdonald postulated that the development and fielding of increasing numbers of precision-guided munitions would allow a force to carry fewer munitions overall while maintaining the same level of lethality (if not greater), thus reducing the overall logistical burden and allowing improved mobility and independence on the battlefield.

As a result, defense spending on the development of new precision-guided weapons as well as retrofit kits for existing stockpiles and improved electronics for launch platforms increased by 88% between FY1995 and FY2005. New weapons such as the DTM-975 Ninlil guided artillery shell and SGM-761 Ritsuko missile system entered service throughout the first decade of the 2000s, while procurement of existing weapons such as the EGI-550 smart bomb kits was increased.

As a result of the proliferation of such technologies, it is expected that the modern brigade will have greater lethality than an entire division in the Northern War, and would be able to more rapidly maneuver with a smaller logistics trail. However, concerns have been raised about the cost of such programs and the ability to stockpile a sufficient number of these weapons to fight a major war of attrition if forced into such a situation.

In order to support continuous maneuver, technological solutions to improve reconnaissance and information distribution capabilities have also become more common. The development of the Common Advanced Sensor System (CASS) module now widely deployed on a number of combat armored vehicles has improved the ability of combat units to detect hostile movement, while the Joint Tactical Data Network and Defense Information Network have been developed to improved inter- and intra-unit communication. The addition of UAVs to each brigade's reconnaissance squadron, as well as their frequent deployment at lower levels is also designed to improve surveillance and target acquisition capabilities.

Role of aerospace power

Based on experience in the Northern War and the two Pacific Wars, the Army 1990 report concluded that development of the helicopter as well as modern munitions has significantly increased the prominence and flexibility of air power on the modern battlefield. The widespread employment of the helicopter allowed for the development of much more flexible tactical airlift capabilities for units in the field, significantly improving mobility for units with the benefit of rotorcraft support.

A significant development over the past several decades identified in the Army 1990 report is the rise of stand-off munitions capable of accurately engaging a target at great range. The miniaturization of guidance systems thanks to more advanced and efficient processing systems has allowed the development of lower-cost and more capable stand-off weapons, greatly increasing the flexibility of engagement options. This includes ground-attack missiles such as the SGM-741 Takane as well as more economical guided bombs such as the EGS-56X Mysterium series and glide bombs such as the LGM-123X Stardust Reverie series. The development of fire-and-forget seekers has also removed the need for spotters on the ground in certain circumstances, making them more suited for penetration attacks.

Rotorcraft support has been a major point of development in the Distributed Engagement doctrine, with divisions structured to include at least one full brigade of helicopters and potentially possessing more in the case of air assault units. The development of the attack helicopter armed with anti-tank guided missiles and rockets has significantly increased the flexibility and timeliness of the air support available to division and brigade commanders who can now manage and control their own aviation support.

Included in the Revision 2 update to the Distributed Engagement framework was the reclassification of "air power" as "aerospace power" to reflect the growing importance of space-based support assets, especially in the reconnaissance and communications areas. While existing satellite networks have enabled strategic-level communications between combatant regions, the rise of microsatellites and falling launch costs has led to the development of tactical satellite communications networks, allowing alternative means of communication from the standard radio trunk network and possibly even direct access to satellite reconnaissance footage.

Drones

A particular point of contention in recent years has been the role of drones and other unmanned aerial vehicles in the Army. As of the Revision 2 standard, increasing numbers of drones have been procured at multiple levels, from larger runway-based armed drones operated as part of the divisional combat aviation brigade to personal UAVs deployed at the platoon and even squad level to supplement intelligence-gathering capabilities. Reconnaissance units, in particular the reconnaissance squadron in each brigade and the attack reconnaissance battalion in each aviation brigade have also seen the introduction of UAVs into their force structures to supplement their existing surveillance capabilities.

Criticism

From the outset, the adoption of Distributed Engagement has encountered its fair share of critics. Primary lines of criticism have revolved around three major points of contention, namely cost, clarity, and maturity.

Cost

Perhaps the most common criticism of the Distributed Engagement model has been the cost, both for improved soldier training and the acquisition costs of new smart weapons and the ongoing costs to keep them up to date. Despite efforts to focus on economical solutions and control runaway program costs, expenditure per soldier on equipment, as well as cost-per-mile of most new vehicles has increased noticeably over the past two decades. Critics have alleged that this increase would necessarily resort in the proportionate reduction in size of the Army, as personnel strength is inevitably reduced to continue funding expensive procurement programs.

While Distributed Engagement is an Army doctrine not considered by the Punic Navy or the Carthage Air Forces, rising equipment costs in these branches has also attracted a fair share of critics arguing that the heavy reliance on expensive weaponry actually hurts military readiness, by putting pressure on the manpower pool and resulting in ever more expensive weapons foisted on the government by the military-industrial complex.

Supporters have countered that a large fraction of the rising costs is due to improved benefits and increased spending on welfare, and that the adoption of the brigade-centric Distributed Engagement model is not the root cause of increased procurement costs. Instead, supporters argue that rising equipment costs are simply the expected price of more advanced modern weapons, a necessary expenditure regardless of doctrinal model. Indeed, cost per unit for a number of common weapon systems has consistently increased over time prior to the adoption of the Distributed Engagement doctrine.

Clarity

Some critics have alleged that the Distributed Engagement model is too muddled or undeveloped in the lower-level tactical space, spending too much time developing technologies and insufficient time on the actual tactical employment of these means. While it is expected that brigades would have relatively high levels of autonomy, little has been done to actually develop a cohesive engagement plan to guide brigade commanders in executing whatever their assigned objectives are, leading to possible confusion on the battlefield.

The response has been twofold: that the ambiguities in the doctrine are not as great as alleged, and that officers are expected to have a great deal of leeway as a matter of course, to allow them to adapt quickly to changing technological tools and foundations without being hamstrung by an outdated engagement plan. The doctrine places great importance on the individual initiative of officers and men at various levels, rather than emphasizing a top-down approach to command or a more rigid framework for operations.

Maturity

From the outset, the increasing reliance on technological solutions has been controversial in many circles. In particular, the increasing costs of development and deployment as well as questions about the reliability and durability of new technology solutions have raised concerns that the army could be crippled via electronic warfare, cyberattack, or other emerging vectors. Concerns about the security of battlefield networks to compromise by enemy attack or even accidental network failure have been raised. While the Defense Forces have continued to invest heavily in these spheres as well, the rapidly evolving nature of these fields opens up the possibility of unexpected vulnerabilities and the potential for software flaws to create major problems in the field.

In response, supporters have argued that the emerging nature of these technologies by definition requires that Carthage invest heavily in them, lest it be left behind by other powers. Failure to invest would leave Carthage even more vulnerable than any potential software bug, and that the development of new types of technology and new forms of warfare are simply to be expected in an age of such rapid progress.