Imperial Hyangism

Imperial Hyangism refers to the animist and panentheistic religion as officially practiced in the Anjani Empire and as opposed to modern-day Hyangism which emerged as a response to the spread of Esoteric Shi'ism and Christianity to the Hindia Belandan archipelago following the fall of the Anjani Empire. Imperial Hyangism was a complex belief system centering on the belief in an all-encompassing, all-penetrating entity called Hyang, whose existence Anjanians believed to be the sum of all reality. Adherents believed in the presence of spirits, both benevolent and malevolent, who lived in and frequented the realm of the living. Imperial Anjanians additionally believed in ancestral spirits, ascribing them with the ability to give assistance to their descendants and persuade the Hyang, the universal spirit, to perform certain actions for the advantage of the descendants.

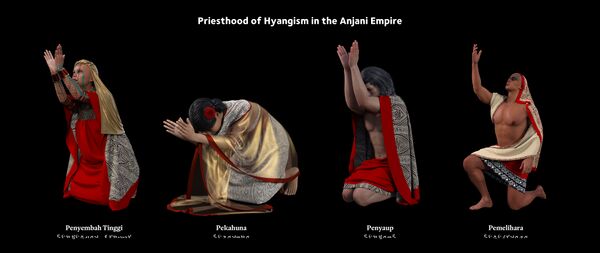

Emerging from a proto-Austronesian belief system, Imperial Hyangism retained the Austronesian belief in the existence of the Hyang, although sometime in the early 3rd century CE, its status as a personal and transcendent god became gradually supplanted with a panentheistic understanding of the divinity. Worship was directed exclusively to the Hyang in order to gain its favour, but other rituals to appease spirits (hahantu) were also done on a daily basis. The Anjanians believed that a balance existed in the world which must be maintained by performing acts of reverence (penyembahan) towards the god Hyang, making pilgrimages to sacred sites and eschewing deeds disliked by the Hyang. At the top of Imperial Hyangism's hierarchical priesthood is the Anjani emperor or empress, in whose person an 'emanation' (ke'atuahan) of the Hyang was said to reside. This quality, unique only to the monarch, was the source of authority (ka-whewhanang) which granted Anjanian sovereigns the right to rule. Despite their status as a dwelling place of divine emanation, Anjani emperors and empresses were not considered divine. They sought counsel from the four Penyembah Tinggi, meaning literally 'the high worshipper', who were the highest of the four priestly orders of Imperial Hyangism, and depended on the priesthood on matters religious and spiritual.

Imperial Hyangism was the first organised religion to have emerged in Hindia Belanda and its establishment can be attributed to the creation of the Anjani Empire by Raden Sabdadiratoe I in YEAR. Prior to the Anjani Empire, Hyangism had existed throughout the Hindia Belandan archipelago as a largely unorganised faith with worship of the Hyang as its only similarity in an otherwise diverse belief system. Imperial Hyangism left behind only few tangible monuments, due to an emphasis placed by Imperial Hyangists on the impermanent and transient nature of life, which translated to religious structures being built with perishable materials. The act of repairing objects and reconstructing buildings and structures was considered a worshipful activity (kegiatan penyembahan), forming part of the religion's Great Conducts. Anjanians meditated on the impermanent quality of all things and practiced a form of repeated affirmations on 'accepting things as they truly are' or as nature intended. This concept is known as Keserahan, one of the most enduring Imperial Hyangist legacies that continues to play an important part in contemporary Hindia Belandan society and thought. Religious texts, on the other hand, were extensively preserved by the many successor states of the Anjani Empire which were re-discovered in the 19th century by Noordenstaater scholars and subsequently translated into modern languages. Imperial Hyangists, as with modern-day Hyangists, worshipped at the Kasembahan.

Etymology

Imperial Hyangism is an academic term given by modern scholarship to distinguish it from modern-day Hyangism. In the Anjanian language, Imperial Hyangism is known as "Sembah Hyang", a term used to refer to both the Imperial and modern stages of the religion.

Background

Beliefs

The Hyangist religion pervaded every element of Imperial Anjanian society and virtually every state ritual and ceremony was connected to the religion. Contemporaneous sources from the Maleu-Kolon Kingdom, for example, described the Anjanians as an overtly religious society.

The societies which preceded the establishment of the Anjani Empire had a nascent belief that spirits existed within certain inanimate objects and inhabited various places in the world. As these societies grew to become what resembled an early state, this belief gradually morphed into a complex system which provided the emerging civilisation with explanations for various natural phenomena and justification for societal norms as well as laws that governed society. Etiological myths were also formulated to provide explanations for various aspects of Anjanian life. Imperial Hyangist beliefs were shaped, initially, by the Anjanians' observation of the world around them; this way of perceiving the world became a framework for the Anjanians to develop an amalgam of panentheism and animism. The panentheistic aspect of the religion, being the belief and worship of the Hyang as a universal spirit, served to explain the origin and existence of the universe as well as reality itself. Anjanians believed that the Hyang is the universe itself and that there was only a single reality, which depended on the existence of the Hyang. In this regard, Imperial Hyangist theology bears a certain similarity with the Esoteric Shia concept of monorealism. It is thought that this similarity made the spread of Esoteric Shi'ism to the otherwise Hyangist landscape of the Hindia Belandan archipelago much easier.

Theology

Belief in an unseen, formless entity called the Hyang was indigenous to Austronesian cultures, although the Hyang was viewed at first as a spirit which traverses the world as opposed to being the universe itself. The earliest evidence of Hyang worship, carbon-dated to the 1st century, was found in Pasembah Plain on the island of XY in the form of a written inscription on a limestone fragment (ostraka). The fragment bears a simple hymn to the Hyang, calling it a "fashioner of the world", "the thing (sesuatu) that traveleth the seas" and "the spirit which giveth rise to the waves". It is clear that early Hyangism viewed the Hyang as an entity which was at the same time transcendent and existing within the world as a spirit.

The 3rd century CE saw the development of a panentheistic view of the world in Anjanian society, superseding the early conception of the Hyang as a singular, creator entity. By the following century, the Hyang was now considered as a universal spirit encompassing the sum of the created universe. It is unclear why this theological shift occurred and historians as well as anthropologists generally attribute it to a shift in reasoning, from one based on pure observation of the physicality of things, such as explaining natural phenomena with concrete mythological terms, to one based on a more abstract and theoretical reasoning. This, however, did not mean a complete rejection of mythological explanations to the world around them, as belief in spirits which could influence the world of the living continued largely unchanged from Early Hyangism to Imperial Hyangism, the form officially practiced by the Anjani Empire.

During the Anjani Empire, the universal spirit Hyang was said to emanate manifestations into certain people and sacred things. The Anjani emperors and empresses were believed to possess a form of divine emanation which enabled them to rightfully rule as sovereign, an emanation which succeeded from the body of one sovereign to the next. Natural features, such as lakes and mountaintops, were said to be dwelling places of this divine emanation, rendering them sacred as a place of Hyangist pilgrimage. Anjanians believed that visiting these sacred sites was equal to partaking in the holiness of the Hyang, making them sacred by association. This sacredness (faha'atua) endured for as long as they were present within the precincts of sacred sites.

The Hyang was never depicted in any tangible form, but in the later years of the Anjani Empire, an open parasol displayed prominently at the kasembahan (Hyangist place of worship) served as an object of worship and reference to the Hyang. In contrast, spirits were often portrayed in the form of statues, totems and sometimes paintings.

The Hyang was addressed to in hymns by various names and epithets, depending on the purpose of the hymns. On one stone inscription found in Alas Kerbau, the Hyang was referred to as the "bringer of rain who is rain itself" and "the subduer of the sky who is the sky itself", strongly suggesting the panentheistic nature of Imperial Hyangism.

In the Crossing of Maraki'a, one of several Imperial Hyangist scriptures, the Hyang is described as follows:

"O Hyang, thrice blessed, pure and mighty, of beauteous countenance! Thou vanquishest the lelembut with the word 'pigi sana,' and the sun riseth in thy company. My being, my soul, my heart, my highest hope, O Hyang, the Great Ruler over the waters, O thou who art my Mother and my Father."

Spirits

Another important aspect of Imperial Hyangism, which survived to this day in modern Hyangism, is the belief in spirits (hahantu) which inhabited the world. Imperial Anjanians believed that these spirits took many forms and could influence the world. The dwelling places of these spirits were often inanimate objects endowed with a special quality enabling them to become spiritual vessels (parnampung). In addition, spirits also inhabited natural features, such as trees, mountains and bodies of water. Although worship was offered to the Hyang alone, Imperial Anjanians also revered spirits, especially those of benevolent nature. Numerous cults centring on the reverence of place-spirits

There were numerous kinds of spirits in Imperial Anjanian mythology, but the three main kinds were accepted to be the memedi (meaning frighteners), the lelembut (ethereal ones) and the lekasar (malicious ones). A class of benign spirits, or lekasih, who were thought to be the spirits of ancestors who had gone to the world of spirits, occupied a higher status than other types of spirits. Some spirits were known to guard sacred places; these were known as the demits.

The memedis, Imperial Hyangists believed, were incapable of causing harm. They merely frighten or upset people unlucky enough to cross their paths. They are known to inhabit isolated areas and may disguise themselves as family members, friends, or relatives in order to fool their victims. Memedis can also take the appearance of animals or floating disembodied parts of the human body. Memedis are thought to be typically harmless, although this does not exclude them from causing indirect harm to their victims. As written in the Kesaton, some memedis, such as genderuwos, are known to kidnap innocent children and transport them to the domain of spirits. Once kidnapped, a child cannot return to the living world unless and until they are saved by the prayers of their family members. According to Imperial Hyangist literature from the 9th century, memedis prefer to throw pebbles upon house roofs on specific nights of the year.

Cosmogony

Anjanian religious texts dating from the time of the Anjani Empire relate that in the beginning, only the Hyang existed but this solitary existence was disrupted at some point in time by the Hyang's desire to fashion a world of creation. This desire of the universal spirit caused the world to come into existence, beginning with the creation of the sky, the land and water. Earlier texts from the 3rd century told a different story, however, in which the Hyang was said to make space in his all-encompassing existence for creation to fill.

Cosmology

Eschatology

Keserahan

Scriptures

Kesaton

The Kesaton is the primary scripture of Imperial Hyangism.

Crossing of Maraki'a

Priesthood

Imperial Hyangist priesthood was divided into two hierarchies. The elects, who were exclusively made up of women, occupied the highest position in Imperial Anjanian society after the Imperial family, whilst the ordinaries ministered to the masses.

Elects

At the top of the Imperial Hyangist priesthood are the four penyembah tinggi.