Kien-k'ang Rapid Transit

KRT Logo | |||

Diagonal line | |||

| Overview | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Owner | City of Kien-k'ang | ||

| Locale | Inner Administration | ||

| Transit type | Rapid transit Light rail | ||

| Line number | 12 heavy rail 13 light rail | ||

| Number of stations | 360 heavy rail (295 separate locations) | ||

| Headquarters | Blue Brick House | ||

| Operation | |||

| Began operation | 1883 (Urban Railway) 1948 (merger) | ||

| Technical | |||

| System length | 250 mi (400 km) | ||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge | ||

| |||

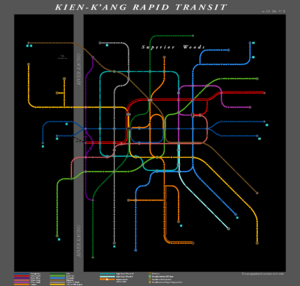

The Kien-k'ang Rapid Transit (建康鐵邑道, rf kyan-k'ang-l′ik-qrep-luq; abbrev. KRT) is a rapid transit and light rail system serving Kien-k'ang and surrounding counties, including Tips, Daks, and Ning, within the Inner Administration. The system is owned by the Kien-k'ang City Railway Company, which is a city-owned company operating under special Parliamentary charter which grants it the exclusive right to build and operate urban railways built after 1948. The KRT is the most-patronized rapid transit network in Themiclesia, with 4,002,010 daily trips taken on average in January 2021, and the 11th-largest, by number of stations, in Septentrion. KRT's network is integrated in places with National Rail, the Inner Regional Rail, and bus services.

The KRT's origins can be traced to two railways: Urban Railway of Kien-k'ang, an elevated network opening in 1883, and Metropolitan Underground Railway, proposed in 1880 imitating Anglia's system but only opening in 1899. Both expanded from the city's docks and commercial heart into the suburbs and rural areas. Other underground and elevated lines opened in the 1900s through 1930s, using a mixture of steam and electric power. The Electric Underground Railway built the first deep-level line with the tunnelling shield method and used electric current for adhesion. Four operators went under common management in 1947 and merged in 1948. The company operated many tramways but have since ended service on most and fortified a few as light rail lines in the 1970s.

The KRT's modern network encompasses 13 rapid transit, 10 light rail lines, and the Kaung ferry. All rapid-transit systems operate with exclusive rights-of-way, while light-rail routes have a mixture of exclusive and shared rights-of-way. Lines may be underground, level, or elevated, and many with a combination of them. All modern rolling stock are eletric multiple units, save for heritage services which occasionally run with preserved steam locomotives.

History

Precursors

In 1858, the Qlin Temple Terminus was erected as the termination of the Traverse Railway that operated between Kien-k'ang and the port city of Q'pa. Trains crossed the Kaung over Bridge Eight then made an S-shaped curve to provide a reasonably gentle grade from the height of the bridge, which was 15 foot from the ground level. Owing to the geometry of the line, the tracks crossed the Q'pa Road, a major highway into the city, at an oblique angle, before approaching the terminus with five platforms. The obstructive and rather prominent viaduct as well as a deeply hated level crossing apparently influenced the city's civic leaders, who in 1872 barred the construction of level crossings within the confines of Great Kien-k'ang, the traditional borders of the city. The later effect of this ordinance was that many metro lines run at grade outside the city and only run underground or overhead within its borders.

As a result, the two newer termini of the city, Ferry Wharf and Tlang-qrum, were built abutting the city's borders to the southwest and east, respectively, but did not enter it. This set them a considerable distance away from the real commercial centres of the city as well as the residential areas of the wealthier classes, a situation not disliked by the cab and lorry drivers. In response, the operators of Ferry Wharf Terminus and Tlang-qrum Terminus each hired teams of cab drivers to provide access to either the passenger's residence or a more central area for discharge.

At the instigation of the railways, an elevated section of track, one-mile long, was demonstrated to the public on Jan. 13, 1873. It utilized a steam locomotive pulling coaches twice an hour between Kam Manor and the Vermillion Gate. The railway ran on temporary wooden trestles and was elevated 12 foot in the air. This height was sufficient for all but the tallest vehicles to pass under the railway unobstructed. While reception was enthusiastic, the City unexpectedly ordered it torn down three years later as it had been erected on public roads without permission, and the creaking and rattling whenever the train moved caused such trepidation that shops on way complained of reduced patronage. Despite fear, the demonstration nearly turned profitable for its sponsors and proceeded without serious accidents.

Early years

Kien-k'ang was a city of about 150,000 people at the beginning of the 18th century and reached an estimated 500,000 by 1850. In 1857, the city documented a population of 325,129, widely though to be a gross under-estimate, as only registered households and tenants were counted. Houses were erected rapidly in the 1830s and 40s to accommodate arriving workers, which only accelerated after 1868 owing to rural depression. Railways from the country reached the fringes of the capital city in 1847, but traffic within city limits was mainly by foot and horse. Population rose sharply after 1870, reaching an estimated 1 million in 1880 and 2 million in 1900. As cities expanded and employers sought to hire from not only near their establishments, commuting as a lifestyle flourished.

In the closing years of the 1870s, the Urban Railway was proposed, with the likes of Krossa and Hadaway guiding Kien-k'ang as to future proects. The city encountered general opposition from residents in wealthier neighbourhoods that proximity to railways was undesirable. Railway backers argued that it would allow fresh goods from the docks in the west to reach markets in the east as well as transport travellers who arrive by boat. Permission was granted in 1880 to erect an elevated railway along the exterior of the city's walls, the supports to be built up from the ditch at the base of the wall. The railway connecting Carp Docks and Avenue Cross, with eleven stops, opened in 1883. This line is now forms part of the Urban line. The elevated network became a success, with the railway building branches after rights-of-way were secured. The elevated railway was, reportedly, the first major all-steel structure in Themiclesia.

On the other hand, the city developed a keen interest in all things underground as a compromise between aesthetics and practicality, the epitome of which in the 1890s was the Central Junction Railway (entering construction 1891) connecting three main-line routes under the city's bustling streets. The Baronet Be (不君, rf be-qur) in 1883 proposed a route connecting residential areas, mainline termini, commercial streets, and industrial areas near the river, over a distance of 7 miles. The city was initially hesitent in view of cab owners' resolved opposition to the plan; unfazed, Be in Parliament secured Government co-operation with a stop at the new Twa-ts'uk-men Station. The line opened in 1899 and is named the Metropolitan Railway after the railway of the same name in Hadaway that inspired it.

In the first decade of the 20th century, the Metropolitan and Urban networks pursued similar goals and therefore created a network that intersected at multiple points. The lines originate and terminate at villages on the (then) outskirts of the city and ran through the Old City, the Twa-ts'uk-men Station, the commercial area to its west, and the dock area on the Kaung. The elevated Urban relied on its right-of-way on the city walls and an additional one to create a circular track aimed at short-distance travellers in the city-centre. The Metropolitan instead built a much larger circle to the south of its existing line, girding much of Kien-k'ang's industrial suburbs to its south and connecting back to the Old City in the east, hoping to tap travellers emerging from the mainline terminus heading commuting southwards.

Relying on the ability to built more quickly, Urban also began work on a southerly branch that basically mirrored the Metropolitan's right-of-way. The two railways quite soon converged on Mrek Road for a 1.2 km section and were in construction at the same time (1904 – 06). Complaints were heard that the Metropolitan was excavating the road far more and earlier than necessary expressly for the purpose of preventing Urban from erecting its pillars; Metropolitan responded that the apparent irregular shape of its route was only to avoid heavier buildings and their larger foundations, and it was "a technical and lawful necessity" to excavate more than the eventual width of the line. The Urban then built its three stops over Metropolitan's three stops and converted nearby buildings to serve as commodious lobbies where passengers could wait in a sheltered space (the Metropolitan did not provide any circulating space).

While the Metropolitan continued to launch suits against the Urban that its tunnels were subsiding under "unlawful and egregious" loads from the overhead trains, the two railways had a relationship friendly enough to agree to co-ordinated tram services in the eastern suburbs.

Rapid expansion

The viability of short-distance railway transit being demonstrated by the Metropolitan and Urban networks, the Northeastern Railway, which operated several main lines, underwrote the Central Railway that enabled its passengers alighting at Qlin-tsung Terminus to go north and south. It entered constructed in 1908 and completed in 1913. The new line longitudinally transected the circulating parts of both existing railways and connected the relatively affluent areas to the north, including Raks-de, a very highly reputed marketplace for expensive finished goods. The Central line was built with no goods depots and completely depended upon passenger traffic, and it was also the first to run in the walled city and near the palaces for a significant part of its route. Running through an area dominated by expensive properties was only possible with Northeastern's immense treasury.

The Central line created the system's first underground crossover to avoid intersecting Metropolitan's tracks; however, their stations were built separately and was only connected in the 1920s. Taking the example of Metropolitan and Urban, the Central line also opened a loop track that circulated further to the north of Urban's loop

While Metropolitan and Urban were arguably in a competitive relationship in the city centre, their lines only a few blocks apart and converging at places, divergence and branches on their lines' extremities served distinct communities. Metropolitan added a five-mile branch to its line in 1906, and another by 1915; as these areas were further away from the city, they were built at ground level rather than underground. The Metropolitan network was in a "wrapped candy" shape by 1915, with services running diagonally and sharing tracks in the centre of the city, increasing frequency; the candy part of the system ran circulating trains that provided services every 5 – 6 minutes during trading hour, compared to 15 – 20 minutes in the countryside.

The most deadly accident on the KRT occurred in 1913 when a Metropolitan train crashed into the end of an unfinished tunnel due to an switch left set to it by inexperienced workers. The crash and attending fire and tunnel collapse killed over 150 and injured more. Metropolitan nearly declared bankruptcy due to existing debts, liability incurred by the disaster, and a further Parliamentary ordinance to buy walk-through coaches that offered better survivability before it could continue to issue dividends; however, the inability to pay dividends in turn hampered its ability to raise extra money to buy the coaches. It circumvented the order by leasing out its loop route and rolling stock to another operator, since it was not under the injunction and could legally run the old compartment coaches.

After the accident, the Kien-k'ang Council imposed more regulations on the construction and operation of railways within city borders, citing the fact that railways in the city deal with tight tolerances, proximity to foot traffic, and more advanced construction techniques such as elevated or underground sections.

By 1920, there was still no route serving the growing southeastern suburbs. While Central sought to expand in that direction, rights to lay lines there were unexpectedly tendered to the Electric Underground Railway. EUR introduced the tunnelling shield to Themiclesia and excavated the first deep-level railway, which by a special act of Parliament could be done without purchasing the land above the line, if the tunnel was more than 25 metres underground. Thus the initial investment was thus lowered, at the cost of slower and more expensive digging. In 1928, the Southeastern line opened, connecting to the Central line in three places and competing with it. The Southern line entered construction in 1929 and was meant to be EUR's challenge to the Metropolitan, which, despite its cramped coaches, was still the most popular line.

Despite any apprehension towards the sheer depth of the EUR's stations, meaning they could only feasibly be entered by novel escalators, electric adhesion obviated the smoke and cinders that clouded hitherto rail services in the city. EUR's success drove the other lines to abandon steam adhesion at speed, though its business activities also included covert funding to smoke abatement (later known as clean air) activists—a direct affront to Urban, Metropolitan, and Central, all of which relied on steam power in the 20s. With smoke abatement slowly gaining prominence, public pressure was applied on the other lines to electrify, from which EUR profited by selling its electricity to them—at a profit and to hike up their prices.

Pan-Septentrion War

During the Pan-Septentrion War, the KRT's services continued in operation until 1939, when advancing Menghean forces began bombing the capital city. Services continued to be passenger-oriented as freight was difficult to tranship in constricted underground spaces. The railways within the city were considered priority targets for enemy bombers and thus were declared unsafe by government authorities. The deep-level lines served as an ad hoc air-raid shelter for those unable to find alternatives; passengers sheltering in the Central line unfortunately encountered a bomb that penetrated into the station. As the front progressed towards the city's limits, the tunnels were blocked to prevent infiltration through them, as they ran under the city's fortified walls. During the siege of 1940 – 41, most of the KRT network was under occupation, though their usage of the network was attended by the same problems that met the Themiclesians.

By the time the siege was lifted, the KRT network had been severely damaged by intentional and unintentional action. EUR's power plant had been destroyed during the bombing raids, 10 out of 14 depots were cluttered with wreckages, and half of the coaches were unsafe. On the routes, four points on the Metropolitan and three on the Central lines collapsed due to bombing, and hundreds of segments of the Urban network were in need of rebuilding or replacement. Limited services resumed on Dec. 20, 1942. Repairs progressed intermittently as vital resources were commandeered for the war effort in eastern Themiclesia. Metropolitan and Central resumed full operation in 1944 and 1945 respectively. Urban re-opened between 1945 and 1947. In this period, only the City and Southern lines remained fully operational, contributing to the UER's revenue baseline considerably.

Post-war

Common management

During the repairs between 1941 and 1947, negotiations occurred between the City and its four main rapid transit operators. All four verged on bankruptcy due to suspensions to services on account of war and damage, and cash needed for crucial repairs was short, with the banking sector still under public control. It was decided in 1944 that the four operators' lines would be bought by the city and then leased back to the operator, through which process the city underwrote the heavy costs of expanding and maintaining routes. The operators guaranteed a certain frequency of service, and in return, the city would receive a fixed percentage from the operators' ticket revenues.

However, under the Railway Act of 1921, which enacted price controls on third-class tickets on the basis of mileage for all railways, operators were unable to turn a profit, and to redress this situation they agreed to run only one third-class train each in the middle of the night, effectively forcing the entire city to pay first- or second-class fares on re-badged third-class accommodation. This scheme becoming public on Jun. 2, 1948, the city's unions threatened a general strike, and industrial leaders, alarmed and unwilling to pay for busses to transport their workers, spoke in sympathy with the unions. The city responded with a gentlemen's agreement to underwrite some of the operators' obligations in exchange for continued third-class service at the agreed frequency.

Only a few months later in November, the city further purchased controlling interests in the operating firms. By 1953, the names of operators were reduced to names for the lines, and the modern name of the network "Kien-k'ang City Rapid Transit System" was printed on tickets. The "City" was initially added to emphasize the role of public management but was dropped in 1959 in a rebranding effort.

University line and Southern line extension

After the end of the Pan-Septentrion War, the city was tasked with settling thousands of veterans and citizens who had lost their homes during the war. By 1945, temporary shelters erected after the end of the siege were ageing and fomenting crime and dissatisfaction. The city hoped to create new towns in its eastern and western fringes for those in need and to reduce density in the core, then blamed for the city's many slums. To provide access to the city, the University line was quickly approved to serve a commuting population created by the exodus. It was the first line built under public administration and opened in 1953. Unlike the previous lines, built to reach established communities, the new line reached new settlements that were only then under construction. The completed line was over 30 km long and had 32 stations.

In a similar vein, an eight-stop extension to the South line was completed in 1952. Both projects took advantage of the public roads to erect elevated sections in less populated areas, accelerating construction and reducing costs.

The University line was built with tunnel-shield technology, and most of its tracks were some 30 metres or more underground. This depth permitted concourses to be added above the track, which funnelled passengers transferring between lines. These concourses were particularly useful at places where two or more existing lines converged but were not connected. For example, at Lats-bring Street, where the Metropolitan, Urban, and City lines intersected, passengers needed to emerge from one station and go to the entrance of another line, which added to the existing crowds on the streets; the University line's new concourse functioned as a shared lobby where all these stations could be accessed. The University line was billed as a "the modern line for the modern age" and included buzzers indicating approaching trains and electrical signage clarifying train destinations.

Docks Motorway conversion

Though the importation of private motor cars remained banned until 1953, car ownership in Themiclesia, particularly in cities, was projected to increase. To redress the limited width of streets in Great Kien-k'ang, it was proposed as early as 1939 to convert the elevated railway network—called the Urban Rail by locals after its original operator—into a motorway network. According to its proponents, the finished system would quintuple the throughput of streets while alleviating congestion below, and conversion would be fast and cheap.

The city settled on a plan to convert only part of the system, encompassing the part of the Urban line from Fortress to Elephant Crossing and the Docks line from Elephant Crossing to Flag Park. The plan left open the option for the conversion of the other parts of the overhead system should the current conversion prove successful.

Critics of the elevated network were divided about the plan: many were worried that the same negative externalities of the railway would persist in the motorway, and most were not convinced that property values along the planned motorway would improve. Others, however, thought that cars produced less noise than the electric motors of trains, and the motorway's backers emphasized that "cars never screetch along bends". The city's administration was also concerned about the plan's politics: socialist politicians and railway unions decried the plan as one to "convert a poor man's road into a rich man's road", as "private motors" were still thought of as a symbol of wealth. The counter-campaign's slogan was "Rg 0.005 not Rg 1,000", contrasting the cost of a ticket and that of a (expensive) private car.

In 1952, work began on the conversion. The conversion process was neither as fast nor as cheap as the city had hoped: apartment blocks were demolished and intersections widened to add car ramps. The motorway, opening in 1957, was not considered a major success, and the second stage of the project over the spur to the north, was shelved, not least under pressure from railway unions and lobbies for the convenience of commuters. As a motorway, the corners were too sharp, and the return of combustion waste irritated residents along the line. The Docks Motorway did become an arterial road for those seeking to cross the city from its northwestern quarters to the southeast, but few commuters used it.

Integration

In 1963, Parliament reformed the local government of the Kien-k'ang and merged the hitherto-separate Rapid Transit Commission and Public Tramways and Omnibus Commission to create the Common Public Transit Board. By bringing them under one authority, it was hoped that the two systems would no longer comopete and instead form a unified network. However, the process met resistance at every stage against redundancies proposed by authorities. In June 1964, the railway and bus unions together declared a strike that lasted 12 days and cripped the city's transportation. While the strike resulted in concessions, some leaders in the automotive industry eagerly capitalized upon the opportunity to paint public transit as an outmoded and unreliable system.

As the policy of integration proceeded, planners were encouraged to consider the potential and requirements of motor vehicles, and more radical ones, such as Drs. Mir and Nya in 1959 – 64, produced studies on the assumption that the ownership of cars would soon render many less-used bus or train routes redundant. In the 60s, the Board's attention was focused on improving popular tram lines, which were grade-separated or otherwise given preferred rights-of-way such as dedicated lanes and signals. It was believed that reliable tram lines functioned as branches or extensions to rapid-transit routes, making the latter more accessible and attractive. On the other hand, trams in the urban core were removed. The improvement of tramways had the advantage of economy over the construction of new railways in small towns.

The privatlization of the National Rail's local lines in 1969 in the Inner Region presented a new challenge to the CPTB

Super Metropolitan and other super lines

In the early 60s, the city was embroiled by the question whether and how the motorways should be led into the city. The M1, M2, M9, and M13 all terminated in the outskirts of Kien-k'ang, but to reach the city-centre a driver would still need to cover about 8 – 10 km over city roads, which were perennially congested. Some estimates put the average speed over city roads at rush hour at 10 MPH, and others declare that walking was faster. Traffic often poured into the city only to access another motorway leading from the city. Parliament funded a pilot project to bring the highway exits closer to the city by running them underground, but the cost of an underground highway was found "unconscionable" compared to that of an underground railway considering the number of people moved; the underground highway project was dropped in 1963.

A series of articles on The Times of Kien-k'ang, amongst other papers, suggested that driving to the city remained popular, even from places with railways and under appalling traffic, because railway carriages were excessively packed and made too many stops en route to and within the city, and from a station the commuter still needed to walk or make a bus connection. Thus, driving was not much slower and provided the comfort of a private cabin. The Metropolitan line seems to have inspired this criticism, with very dense stop spacing in Kien-k'ang, often only 0.3 to 0.5 km, which meant trains could not gain much speed before stopping again. The CPTB said that enlarging Metropolitan trains would effectively require rebuilding the railway as they were already as large as the loading gauge permitted.

Thus, a new planned called the Super Metropolitan, which appeared in 1931 first as an artist's fantasy, gained public attention. The line would closely mirror the corridor served by the Metropolitan but be longer and have larger stop spacings as well as faster trains. The government, defeated in Parliament by the cancellation of the underground highway, endorsed the Super Metropolitan as a substitute and added parking towers in the line's peripheral stops, so that car-users stow their vehicles and avail the railway into the city.

The Super Metropolitan was then integrated into a more general plan to re-organize up-bound commuter trains, which must be either shunted in the Central Junction Railway or go through a wye to the down side, causing operational difficulties for the mainlines using the tunnel. The plan called for a new corridor into the city-centre for commuter services running from as far as 100 km away, at main line speeds (up to 100 MPH) as opposed to the current speed of the Metropolitan (about 15 MPH in the 60s). The integration of the Super Metropolitan required the corridor to be re-situated along the most densely populated areas, rather than the more oblique one planned, and provide transfers to the original Metropolitan line. The plan was published by the CPTB as the Super Metropolitan Railways for More Distant Commutes.

It has been noted that the "super" lines were inspired partly by the success of the Central line, which was triple-track throughout its trunk line and quadruple-track at various stations. While this arrangement was intended originally to avoid conflicts between branch and trunk operations, it also ran express services on the spare tracks, which brought passengers into the city with greater efficiency. The speed advantage was particularly notable in the suburbs as straighter tracks there permitted higher speeds. For the 1960s and 70s, the CPTB focused most of its resources on integrating the KRT system with the Exchequer District Railway network, which within the city centre ran as "super" lines that provided faster services between points already connected by existing services. The "super" lines were very expensive to build, even with restrained interiors, as their tunnels were larger, straighter, and deeper, and integration with existing stations needed to be effective.

The chairman of the CPTB averred to Parliament in 1965 that many commuters "now have in their possession a private car and therefore a genuine choice between commuting by car or rail", and the railways "must substantially improve to remain competitive with private motor at greater distances, for gone are the days when railways competed with the foot". The CPTB's attitudes were presaged by National Railways, which made its first investment into high-speed railway the decade before to remain competitive for longer journeys, realizing from foreign experience that intercity driving would soon become popular.

Citadel line

The Citadel line originated in consistent calls to restore the Docks line that had been converted to an elevated motorway in 1954. While the city was never happy about the conversion, it being costly to maintain and always congested on account of its speed limit (25 MPH generally, 15 MPH on curves) and narrowness (two lanes), the motorway was billed a motorist's lifeline through the city centre: while the streets below could come to a complete standstill, the motorway rarely did so even though its speed was slow. The city had studied this possibility nearly as soon as the conversion was complete, but its fiscal commitments to the Super Metropolitan prevented concrete plans from adoption.

In the early 70s, a new "super" line approaching the city from the northwest was in consideration. This was amalgamated with the plan to revive the Docks line, as a triple-track railway with express capability, reaching further into the suburbs than the original Docks line (which only served Great Kien-k'ang). The Citadel line was actually a substantial improvement over the Docks line, which ran overhead and had very limited operational speeds owing to its sharp corners (which also beset the Docks motorway). This line entered construction in 1975, and its first operational section opened to the public in 1979; the entire line was not finished until 1990.

The Citadel line is artistically dominated by brutalism and characteristically has unadorned concrete walls in both the interior and exterior. This has generated considerable controversy as the predominant exterior material for urban houses is brick, and the modernistic, concrete exteriors were criticized in some quarters as disharmonious. After local protestation, the CPTB redecorated some of the exterior faces with randomly-placed bricks "like islands in a sea" of concrete. The Citadel line was also the first line to feature significant public art installations in the form of statuary and murals, all executed in concrete.

Being the last line to come online for some years, the Citadel line often the face of the KRT system. The architecture of the line is held to exemplify changing attitudes from pre-war, profit-oriented austerity, post-war utilitarianism, and towards growing attention for aesthetic and comfort.

Tibh and Tibh Airport Line

Centennial Line

The Centennial Line opened in 2019 and was named for the expected centennial year of Empreor Qrirq in 2016, running from St. Ignatius of Gen to Prak Market. This line is part of the transit component of the 2050 Plan that the city announced in 1998 to guide land development over the first half of the 21st century. To address urban sprawl resulting from suburbanization since the 1960s, the city's priority is to encourage the development or improvement of land close to the city centre or other urban centres, to "minimize the meaningless distance between the workplace and the home that increases time waste, pollution generated in transit, and congestion on public roads that wastes other people's time".

Lines under construction or planning

Granary Line

Outer Loop Line

The Outer Orbital Line (越袁涂) is a planned orbital light metro line around the Metropolitan City; the route will be 71 km long and has 35 stops at opening, and the orbital diameter is around 25 km from city-centre. The line will intersect various existing railway services on 24 points on its route and is meant to allow riders to "hop" between different satellite cities without having to go into the city to change lines.

While Kien-k'ang already has two circular routes, they are both too close to the city-centre to be judged quite useful for the purpose of going from one satellite city to another. The inner circle, which is operated as part of the Metropolitan Line, has a route length of 4.7 km, and the other loop line is found on the commuter railway service and assembled from existing mainline routes (with a few additions), measuring 21.7 km.

Network evolution

Lines

Rapid transit

Medium-capacity systems

| Name | Services | Peak headway (min) |

Off-peak headway (min) |

Length (km) |

Stations | Construction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Museum – Glassworks | 4 | 10 | 11 | 24 | subsurface |

|

Glassworks – Armoury | 4 | 10 | 4 | 7 | subsurface-ground |

Light rail

Fares

Rate

The basis of fare calculation on the KRT since unification in 1948 is the number of stations travelled. This system effectively subsidizes travel through the outskirts of the city and its suburbs, where stations are farther apart, while travelling in the urban core, where stations are nearer, is more expensive. The minimum ticket cost is for three stations on the rapid-transit system, but this limitation is absent on light-rail lines.

Ticket media

| Media | Accepted at | Single ticket | Single seasonal pass | Return seasonal pass | Super pass |

Group pass |

Courtesy pass |

Staff pass |

Dependent pass | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KRT or LR |

KRT to LR |

KRT to IRR |

KRT or LR |

KRT to LR |

KRT to IRR |

KRT or LR |

KRT to LR |

KRT to IRR | |||||||

| Paper (conventional) | Manned gate | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Paper (magnetic) | Automatic slot | Yes | Yes | Maybe | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Seasonal Magneta | Unpainted swiper | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Stored-value Magneta | Green swiper | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Concession Magneta | Yellow swiper | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Bisa, Rastercard, Hallian Express, Dinner Club[1] |

Card terminal | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Intra, Mastero, Alliance | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Dayacom Pay | Phone terminal or QR code scanner |

Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| nPhone | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Samsan | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| FlexiPay | FlexiPay terminal | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

Single-journey tickets

Single-journey tickets may be purchased at a ticketing window, ticketing machine, or designated third-party sellers. These are marked for the date, origin and destination, ticket price, type, and terms and conditions. Tickets purchased at the station are usually good for one journey on the day it is issued, while those from third-party sellers must be dated by the origin station by a clerk, whereupon it becomes valid for one journey on the day it is dated. An undated ticket is not valid for travel. The ticket is punched by the gate clerk at the origin and retrieved by that at the destination. Passengers holding an incorrect ticket are required to go to the fare adjustment desk.

Ticket machines were introduced on the KRT in 1945. The machine, installed in remote stations to replace the ticketing clerk, used a mechanical dial to select the destination station and display the correct price; coins are then deposited into the machine, which identified them by diameter and weight. The customer then rotated a crank to dispense the ticket. Banknotes were not accepted, or concessionary tickets issued. To obtain a concessionary ticket, a purchaser must ring a bell to summon the station master. This machine was unreliable owing to frequent repairs and refills and was withdrawn in 1948. A new ticket machine was introduced in 1960, with electropneumatic buttons selecting the correct destination and automated dispensation; they were installed in and near busy stations to reduce waiting time at ticketing windows, and where repairs and refills were more easily done.

Early tickets were Edmondson railway tickets, which continued to be sold until as late as 1994 from old-style ticket machines. These were made from cardboard and measured 17⁄32 by 21⁄4 inches and shipped in large strongboxes from the ticket press to the requesting station, where they were sorted and stored in chests facing the clerk. This was typically done in the middle of the night when no services were running. The ticket press was retired from revenue service in 1995 and now prints commemorative tickets. The 1960 ticket machines did not use pre-printed tickets but a drum-based impact printer printing to a continuous roll of ticket paper; these were broadly adopted in the same decade and remains in service at some locations. In 1992, magnetic-striped paper tickets made their debut, enabling single-journey tickets to be checked automatically; this format is the dominant format today.

The letter next to the origin station indicates the venue where the ticket was purchased. Manned ticket windows sell tickets marked with a number, from 1 upwards; ticket machines tickets are marked with a letter from A to Z and then AA to ZZ, and so forth. The market "ZZZ" means the ticket is issued from the station office, which occurs when the ticket requested is not machine-printable. Magnetic-striped and older paper tickets have slightly different typesetting. Magnetic-striped tickets have a serial number printed on the bottom right corner, whereas the older-style have a serial number printed at the back.

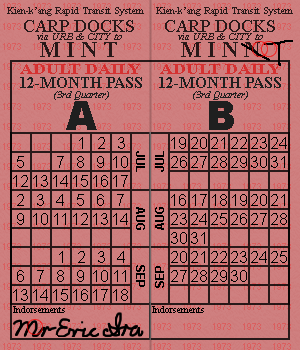

Seasonal pass

Seasonal passes (季札, kwīts-sqrūt) are available for repeated and regular journeys, sold in 1-month, 2-month, 4-month, and 12-month variations. The seasonal pass is non-transferable and can only be used in combination with a government-issued identity card; it can be re-issued for a fee if lost. The pass is good for one specified journey and cannot be re-used on the same day, or used on weekends and statutory holidays. The physical pass is a folded cardboard booklet with holes for each day the pass is valid, to be punched by the gate clerk for admission; the pass shows the origin and destination for which the pass is valid. The clerk at the destination seeing the pass covering the journey will not demand to see a ticket.

Concessionary rates compound with seasonal pass discounts; thus, a secondary school student travelling under a 12-month pass would receive a compound discount of 0.7 × 0.75 = 0.525 → 47.5% off.

| Term | Discount |

|---|---|

| 1 month | 10% |

| 2 months | 15% |

| 4 months | 20% |

| 12 months | 30% |

Super pass

A super pass or tourist pass is a ticket good for one traveller over a specified period, for an unlimited number of journeys. It is issued in several durations—1 day, 3 days, 7 days, and 28 days. It is also billed as a "tourist pass" as it effectively eliminates the need queue for tickets anywhere on the KRT network, therefore saving time and effort for tourists. The cost of super passes is calculated on the basis of four journeys of five journeys per day the pass is valid, but no discount is applied. Like a seasonal pass, it is issued to a specific traveller, must be used with an identity card, and can be re-issued for a fee if lost. Concessions cannot be applied towards the purchase of super passes. Super passes are also sold by travel agencies, convenience stores, book stores, and department stores in the interest of convenience.

Magneta cards

Magneta cards are magnet stripe cards that either store a seasonal pass or contain stored value for pay-as-you-go functionality. The card itself uses a proprietary format and is obtained with a deposit of $50, which is redeemed when the card is returned to the KRT. Both cards can be purchased at a ticket counter. Terminals are available to recharge the stored-value Magneta, but a seasonal ticket can only be loaded into a seasonal Magneta at a ticket window.

The seasonal pass Magneta was introduced in 1972 to replace punching and checking seasonal passes, which took longer than a single-journey ticket. The word "Magneta" in Shinasthana was a pun on the word "profit". A seasonal pass is stored as digital information in the magnetic stripe. By using a Magneta card, the traveller could walk through a dedicated gate and thereby avoid queues at the ticketing window and gate; additionally, exterior transfers can be made without obtaining a transfer pass. At launch, Magneta was met with ambivalence as cards were susceptible to data corruption, but they gained in popularity in the years following.

Stored-value functionality was introduced in 1975 in a separate product that was also branded as Magneta. The value stored on the card is recorded as a 16-bit word, which hard-limits its maximal value to €655.36 (about $2,608.33 in 2020 Int'l dollars). However, the stored-value Magneta is incompatible with the seasonal Magneta and was accepted at different gates. To avoid confusion, the stored-value Magneta was coloured green (the same as single-journey tickets) and accepted at gates painted green, while the seasonal Magneta remained uncoloured and pass through the ordinary stainless-steel gates. This situation changed in 1993 with the combined magnetic gate, which had two readers mounted on it and thus can—technically—read both cards and trigger the same blocking mechanism.

In the 1990s, Magneta cards for concessionary fares were introduced. These also have stored-value function but are incompatible with the seasonal or ordinary stored-value Magneta and therefore must be swiped at a different reader. The concessionary Magneta's data structure allows the concessionary rate of the holder to be recorded; thus, a Navy sailor holding a concessionary Magneta would be entitled to a 6.25% discount, while a secondary school student would get a 25% discount. These Magneta cards have a yellow stripe across their green surface and are swiped at the yellow reader.

Transfer pass

Stations on older intersecting lines are usually not physically joined together, even though they are now considered the same station for the purpose of calculating fares. Between these stations, it is necessary to obtain a transfer pass, which enable travellers to go between two disconnected stations while paying for a through ticket only once; the pass is issued by the last station on the first line and retrieved at first of the next. A transfer pass can take the form of a magnetic card or paper pass. The magnetic card is obtained in the fair-paid zone in the first station, validated for the next station, and then checked by that station's transfer gate. The paper pass is obtained and collected at manned gates. Where a station connects externally to two or more stations, the magnetic card must be validated at the terminal specified for the next station for a valid transfer to be made; similarly, the paper pass is specific to the station to which the transfer is made.

For example, the Green Street station on the Urban Crossover connects externally to the Green Street stations on the Metropolitan and Central lines; a passenger making a transfer from the Crossover to the Central would need to obtain a transfer pass in the Crossover, validate it at a terminal marked for "Transfer to Central", exit the station at a red gate marked as "Transfer to Central", enter the shared Central and Metropolitan station, and feed the card into the corresponding red gate marked as "From Crossover". Paper passes, if used, would be obtained and deposited at manned gates.

These passes were introduced in 1926 to incentivize travellers to travel across lines by allied operators. Transfer passes contain fine printing and secret punch marks, which vary from day to day and place to place to prevent forgeries. Passengers holding the Magneta card do not require transfer passes but must still walk through specfic transfer gates, coloured red, which records that the journey remains in progress.

Concession pass

Concessions are available for various groups. According to 2020 rules, the following discounts are in force:

- 5% off—concession for Consolidated Army

- 6.25% off—concession for Themiclesian Navy

- 10% off—concession for university students

- 25% off—concession for secondary school students

- 50% off—concession for children under 12

- Infants (under 6) accompanied by adults travel free of charge

Concession-holders must apply for a concession pass, which is issued by the Common Public Transit Board at various locations. The purpose of a concession pass is to certify that the traveller qualifies for the concession claimed, because proof is not always conveniently carried. To obtain a pass, a university or secondary school student must approach the CPTB with documents such as tuition invoices and enrolment records from their respective institutions, whereupon concession passes are issued for the term of 12 months and can be renewed. A similar process is applicable for soldiers and sailors in active service. Children under the age of 12, whether currently enrolled or not, obtain their passes with a signed letter from the Home Office, which their parents can apply for, as identity cards are not normally issued to children. The pass is provided to a ticket clerk or machine to obtain the conceded fare.

Courtesy pass

A courtesy pass is issued by KRT for dignitaries and their agents, permitting an unlimited number of journeys for an indefinite period. Currently, peers and members of parliament are able to claim an undisclosed number of courtesy passes for their staff's and their own use. A courtesy pass is a paper pass that must be shown to a gate clerk to obtain entry. It is unknown if KRT couretsy passes are ever revoked, though many have returned them after their entitlement elapses. KRT does not disclose what this pass looks like, but leaked photos suggest at least one design consists of a red booklet with yellow lines running diagonally.

Staff and dependents passes

KRT employees enjoy a 50% discount on all fares in its system, and this discount compounds with seasonal pass discounts. A 25% discount is applicable to KRT employees' families. These passes are paper passs that must be shown to the gate clerk to enter and exit the system.

Group pass

Groups more than 12 people travelling together, entering and leaving the system at the same station, can travel under a group pass. The pass is discounted according to the number of individuals in the group. Such a group will enter and leave the station through the manned gate.

Infrastructure

Stations

There are 445 stations on the KRT in total, of which 295 are on the rapid-transit network. They may be divided into several kinds depending on the geography and topography of the station as well as the design objects when built and subsequently modified. The remodelling and reconfiguration of KRT stations is ongoing under an active works programme, and as of late 2022 there are at least six stations under active renovation or complete rebuilding.

The standard sub-surface station design in the pre-PSW period consisted of side platforms straddling two tracks directly under the road surface, often less than 20 ft deep. Stairwells connect the street level to one or both ends of the side platforms directly, and the ticket gates were located on a landing of the staircase. Platforms in either direction were not internally connected, so passengers going to the opposite direction must exit the station and re-enter on the other side.[2] Over time, this has come to be regarded as an inconvenience, and at various stations remedial underpasses have been constructed, particularly if transfers to other lines are there possible, but 12 station still exist without such an underpass.

The lack of lobbies in the earlier stations is because passengers were not expected to dwell in the station for any significant time, given the frequency of services (often less than 10 minute headway). This was in contrast to mainline stations, which offered more services and sometimes even food and shopping options. Any extra internal space usually came about as a connection to a nearby building of special interest, such as a mainline railway station, or a nearby station on another rapid transit line. On the Central Line, wider platforms at some stations required the stairwell to emerge from existing buildings, which were often converted into a small exit building. However, in some cases, only the ground floor was converted into an exit, while the upper stories remained in use for other purposes. Such facilities have been extended to the Metropolitan line in some locations or expanded to provide shelter to passengers exiting the station.

On the elevated lines, the changing of directions was usually enabled by overpasses. Most elevated stops tracks were constructed directly above roads, where the height of the tracks (about 20 ft) and road clearance considerations forbade an intermediate level to serve as a lobby. At most stations, ticketing windows were located under the street-side staircases leading up to the platforms; however, this often resulted in long, exposed queues. After the PSW, the public authorities often converted nearby buildings as lobbies and stairwells, which then connected to the platforms horizontally. Where done, the stairwell would no longer obstruct the pavement, but this was not always possible, and the resulting conversions are often unaesthetic.

The provision of internal circulating space was more common on the stations of the Electric Underground Railway. These stations were built deeper that there was no convenient way to access them except by elevator and escalator, which required a landing space to accommodate their mechanisms and travellers waiting to step on them.

The Central line, opened in 1916, set the standard for many design features expected on the KRT's newer lines, such as electric lighting, high platforms, lavatories, and covered waiting rooms. Some improvements arose from poor experiences on previous rapid transit products. The Central line led the industry in Kien-k'ang to pursue commercial integration, leasing stall spaces to entrepreneurs and opening paths into nearby stores, but its more affluent environs, amongst which are six department stores, are credited for this awareness. While the Central line was early branded as "the clean line", referencing its total abstinence from low-grade coal, its embrace of snack stalls and like establishments fostered a line-wide pest infestation that gained notoriety in the 1920s.[3] Ironically, the line's uncontrollable pest problem markedly improved during its prolonged closure in the PSW, and when the line was re-opened to the public in 1944, the leases for food stalls were not renewed.

Deep-level lines, under the Electric Underground, were constructed with sub-surface lobbies, where ticketing and transit occurred.

Platforms

Dimensions

The KRT chiefly operates with side platforms and island platforms, depending on track layout, station architecture, and anticipated passenger volume. Side platforms predominate on the earlier lines, namely the Urban network and the Metropolitan line, as tracks geometry does not need to change to accommodate platforms. On later lines, island platforms are more common at stops where space is less restrictive and where high passenger volume is expected. In the lines built after the PSW, island platforms are the norm in the urban core. Stops with express service on the Central line were built with two island platforms, while the same was achieved on the Urban lines by an island platform sandwiched between two side platforms.

Platform width was generally guided by anticipated passenger volume, though very early estimates are often outdated with respect to modern demographics and operation. For example, the Riverside line's platforms became dangerously congested in the 1910s and 20s, well exceeding the estimates that had guided the line's construction in the 1880s; the operator was forced to position staff at the foot of stairs leading to platforms to prevent overloading; however, as depopulation took its toll on the area, the platforms became more able to cope with passenger volume again in the 80s. In underground stations, changing the width of platforms is impractical and continues to challenge the KRT.

The length of platforms determines the length of trains that could serve it. The Urban lines were designed to serve anywhere between two and eight 50-foot coaches, but the Metropolitan line was meant for six 50-foot coaches. The Central line was designed for trains consisting eight 60-foot coaches. The two pre-war deep-level lines were built for the same configuration and accommodated six 65-foot cars, though these platforms did not need to accommodate an engine as the trains were EMUs.

Facilities

All KRT platforms are provided with passenger information and safety notices, though the manner of their delivery varies. Each platform has at least one route map and one local map showing points of interest in the station's vicinity, and there are standardized signage that point towards trains and exits, even when they are obvious to most travellers. All stations also possess a "train position and approach alert board" introduced in 1958, which uses blocking signals to inform passengers of the trains' positions, and a mechanical bell rings when trains approach. In the Tibh and Tibh Airport line, completed in 1997, a digital information system operates in synchrony with the older system and gives more precise arrival times on CRTs.

On the older lines, blinking lights accompany the arrival of a train, being first introduced in 1920 on the City line. The lights are caused to blink by a series of terminals just outside of the tracks that are closed by a small shoe on the train. The lightbulbs are either buried in the platform, ceiling, or walls. As this system operates independently of warning singal created by blocking, it is considered a redundancy in the interest of safety.

On the University and Tibh and Tibh Airport lines, there are platform screen doors which open with the train's doors but otherwise stay closed and prevent passengers and other objects from falling onto the tracks. Platform screen doors are not present on the other lines, though plans for their addition have been announced in 2005. Tactile paving, always 50 cm away from platform edge, exists for the benefit of both the visually-impaired and other passengers to prevent falling off platforms.

Signalling

Transfers

The KRT has transfer points internally, to National Rail, Exchequer District Railway, Themiclesian High Speed Rail, and the Kei Airport Railway. There are 70 stations where transfers can be made within the rapid-transit network, from one line to another or between branches of the same line. In 13 of these stations, transfers can be made between three or more lines, and in 5, between four lines. There are two stations where transfers are possible between five lines, the maximum on the KRT network.

Within the KRT network, including rapid-transit only, some transfers can be made between two or more fair-paid areas that are physically connected, where travellers can wend from one line to another without passing through a fare barrier. 27 of the 70 transfer stations do not have physically-connected fare-paid areas, and there transfering passengers must obtain a transfer token from the fare-paid area of the previous line and then gain admittance to the other line's fare-paid area with the token. It can take the form of a magnetic card or paper slip, and the former is checked by special "red gates" at both stations, and the latter manually. This arrangement largely reflects the proximity of stops on lines once separately managed, and where KRT has not made a remedial connection, often due to geographic, topographic, or fiscal constraints.

In-station transfer to the IRRR occurs at 15 points on the KRT network. Because the KRT and IRRR do not share their fare structures, it is not possible to go from one network to another without going through respective fare barriers. IRRR lines beyond the city centre are typically at ground level, while KRT lines are usually grade-separated with the exception of the Metropolitan line in some places. Thus, most transfers in this context will require vertical movement. Transfers to the National Rail and HSR networks occur at the same stations as the two railways are parallel to each other within the urban centre. There are nine stations where transfer to National Rail can take place through enclosed structures, and three for the HSR.

Locomotives and rolling stock

Gauges

While all lines of the KRT and light rail run on a 4 ft 81⁄2 in track gauge, the loading gauge varies from line to line as they were built by different operators and under distinct circumstances. That of the Metropolitan line is the most restrictive, at 9 ft 6 in wide and 12 ft 6 in high, and that of the Central line the widest at 10 ft 6 in and 13 ft 6 in high. The height limit on the Urban network is still higher, at 14 ft, but it actually has a narrower width at 10 ft. The width of the gauge on the deep-level City and Southern lines is 12 ft at the widest, but a part of this width is unusable because the tunnel is cylindrical; the maximal width of its trains is about 9 ft 6 in. Moreover, the gauges differ in the roundness of their corners, meaning that diametrically smaller train may still be out of gauge, particularly on the roof ridges, on a wider line.

After the lines were brought under common management in 1948, the Managing Committee considered consolidating the rolling stock to just two forms: a wider gauge for the Central line and the Urban network, and a narrower one for the Metropolitan and deep-level networks. However, the plan met serious objection when it became clear that the Metropolitan line, the busiest in the network, would lose already-limited space, and when both the Central and Urban networks would lose interior space to conform to each others' gauges. After some debate, it was decided that the Metropolitan line would retain its own gauge, while the Urban and Central networks would harmonize to a compatible gauge.

Locomotives

Trains on the underground Metropolitan and Central lines were pulled by steam locomotives until 1928 – 29, but the elevated Urban network, which did not suffer from lingering smoke in stations, used them until 1960. To reduce smoke in tunnels and platforms, engines burned coke rather than coal on the underground lines. The Urban lines, whose earlier sections were elevated, burned coal. The Metropolitan line operated two fleets of 4-4-0 type tank engines, an initial design by Anglian engineer Samuel Burns dated to 1891, and then a domestic design by E. R. Kru & Co. in 1903. The Urban lines operated with a larger fleet of 4-4-0 and 0-6-0 locomotives, all being tank engines. The Central line, with fewer curves, operated with 0-6-0 tank engines.

Unpowered coaches

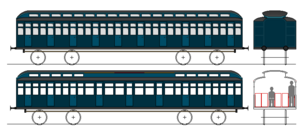

Urban network

The original Urban line began operations in 1883 with all-wood, compartment-style carriages until the introduction of EMUs on their lines in 1962, though they did briefly experiment with a steel-framed coach in the early 20s, which was abandoned due to its weight. Carriages had eight to ten compartments opening directly onto platforms. Urban Railway's trains typically consisted of five to eight 60-foot carriages. First-, second-, and third-class compartments were available, with improved space and comfort for passengers paying higher fares. As provided by railway legislation at the time, third-class compartments were 4 ft 8 in long. Second- and first-class compartments were both 8 ft 4 in. Most compartment coaches had clerestory windows which could be opened for ventilation, though they were also susceptible to catching smoke and cinders from the engine.

The standard third-class compartment sat six-abreast and twleve to a compartment. Second-class compartments sat four abreast, while first-class compartments might sit four or three, depending on the coach. On the Urban network, third-class seats were unpadded, bare wood. Second-class seats were padded and were fitted with individual armrests, while first-class seats were lined with velvet and embroidered with the company's monogram. Unlike the conventional railway, first class was patronized about equally as well as second class. As older second-class stock cascaded into third class, second-class furniture grew closer to first-class, with the result that, by the 30s, first- and second-class accommodations were nearly identical on the Urban, Metropolitan, and Central lines. The lingering difference was in colour: as a rule, second class was funished in blue, and first class in red.

Metropolitan line

Compared to the Urban network's rolling stock, built to main-line standards of the 1880s, the Metropolitan line's loading gauge was restricted by the financial wherewithal of its principal patrons led by Lord Bu and turned out smaller than normal. Owing to the curvature of the underground tunnels, coach length was likewise reduced to 50 ft without chamfering, and platforms were restricted to 330 ft. These dimensions accommodated six coaches if the engine is to be on the platform. The coaches themselves were laterally divided into compartments, opening directly onto platforms on either side. Third-class coaches were 5 ft long—slightly longer than Urban's compartment to compensate for the reduced lateral width. Second- and first-class accommodation were available.

After the 1913 Syar Manor disaster heightened fears of being trapped in tunnels, Parliament legislated in 1914 that all new coaches running on underground railways must have a pathway permitting passengers to detrain at either end of the train, in case transverse doors are blocked. This had already been achieved on main-line express trains, though for access to amenities and not consciousness of danger. The legislation had a five-year grace period ending on Dec. 31, 1919 and mainly applied to the Metropolitan railway where the disaster occurred. Due to their newer completion date, the Central line and deep-level lines never operated with compartment-style coaches.

Central line

Central line was served by notably larger rolling stock retired from main-line service, because the line was owned by Themiclesian Railway, a main-line operator. In the 1890s, mainline gauges were increasingly defined by the dimensions of the Central Junction Railway, through which many trains were expected to pass in services to the capital city; older main-line stock, not quite up to the size limit, were retired from service to make way for more competitive stock. Themiclesian Railways hoped to enter the expanding market of rapid transit and found that its old, wood-bodied stock were still considerably roomier than the Metropolitan's. To gain market notoriety, it heavily marketed its roomier and modern open-style coaches, which did not require retrofitting to conform to the 1914 legislation mandating walk-through carriages.

When the line opened in 1916, the main coach style was its 1878 and 1890 stock, which measured 50 and 60 ft in length respectively. Third-class coaches had unpadded wooden benches, sitting in 3+2 rows facing each other. Second-class seats were padded and sat in 2+2 rows arranged likewise.

EMU

Metropolitan

Urban

Central

Underground Electric

The Underground Electric Railway, which owned and operated the City line and Southern line, commenced services in 1921 with electric multiple units on their deep-level network. This was done as regular ventilation shafts to the surface was impractical along the network, and there were fears that coal fires would struggle for oxygen at the network's depth. Moreover, the UER looked to international successes with underground electrification and marketed its "fireless" network as safe, fast, and reliable. Their early rolling stock, called Class 10, consisted of two three-car sets electrically coupled together and could be separated into constituent sets for operating on branch lines, though this never occurred as the company did not open any branchs. Cabs were located at either end of each three-car set. Due to limited width, coaches had longitudinal seating and sliding doors. Cabs were located off to one side, allowing a connection to be made between two sets in case of emergency; however, passengers were not permitted to venture between sets when the train was in motion.

Because the electric motors did not generate any exhaust, Class 10s were designed with a shortened clerestory window, which measured just 6 inches in height to conform to the loading gauge. These can be controlled by strings in the carriage and angled so as to force air into the carriage. Conversely, because the engine did not rely on steam, the Class 10 did not have heating facilities in the winter, which lines like the Metropolitan and Urban were able to provide.

Accidents

1913 fire

In 1913, the Metropolitan Railway was being extended from Syar Manor with a branch line coming off the tracks just past that station. On January 10, workers travelled in the tunnel via a handcar and set the switch towards the unfinished branch to enter it. Train 62 on the Metropolitan Railway left Syar Manor station at 7:18 a.m. with Nathan Kya as fireman and Mit-nem Pats as engineer, very soon entering the unfinished branch by mistake. Unaware that they had taken an incorrect route, there being little to no visibility in the unlit tunnels, the train rammed into the end of the tunnel. It appears that, realizing that a collision was imminent, the fireman dumped the engine fire; however, cinders from the ashes may have contributed to the subsequent fire. Almost immediately, the wooden coaches caught fire, and passengers could not escape because the doors, swinging outwards, were blocked by the tunnel wall.

As trains on the the Metropolitan Railway were not permitted to leave the station until the train ahead had left the next station, Train 68 was left standing at Syar Manor with the next station, Nam-lin, never reporting the arrival of Train 62. At 7:48, ten minutes past the scheduled departure, the entire eastbound line came to a halt. Permission was granted to Train 68 to proceed with the guidance of a lantern signalman eastwards, and the signalman discovered that the switch was not correctly set, and that a draught had developed due to the conflagration at the end of the tunnel. He entered the unfinished branch and discovered the carriages ablaze. Sounding the alarm, Train 68 was led to Nam-lin, and the fire brigade was brought to the scene with breaking tools. The fire brigade was flustered by the absence of nearby water sources, resorting to an inpromptu hose led from a water main, through Syar Manor station, and into the branch tunnel.

The rescue effort was severely hampered by the coaches on the rear of the train, which, without pressurized steam from the engine, were breaked by the failsafe valve. The fire brigade severed the air pipes and started to drag the intact coach by hand out of the station; however, every time a coach was severed, the fire brigade had to leave the tunnel that an engine could enter it to haul the coach out. As this was in progress, the fifth coach was removed to reveal the fourth coach with a visibly damaged body. It was judged unsafe to pull the coach out, the extent of the damage ahead unknown. Fire brigade members therefore demolished the body to reach trapped passengers, but therein they were impaired by walls between compartments. With the frame of the fourth coach removed, the smouldering wreck of the first three required the water hose to access.

Only after five hours, the fire was fully extinguished, revealing the extent of the casualty. 152 had perished in the fire, with another 75 suffering serious burns. Amongst those who died, 27 were children. The six workers and two train staff were also killed. The workers' handcar was crushed by the force of the impact. The frame of the first coach was completely shattered, having telescoped with the engine, while those of the second and third were badly mangled. The fire had reached the fourth coach by the time the fire brigade worked its way to it.

As word of the disaster spread, shares of the Metropolitan Railway plunged in the L'odh Stock Exchange. Already mired in debt from new construction, it was eventually required to pay over £100,000 in damages after the courts adjudged it responsible for poor supervision of workers; this liability prevented it from undertaking expansions in a relatively prosperous decade. In its annual general meeting of 1913, General Manager and Chief Engineer A. Mar, who had held these positions since the opening of the railway in 1899, was dismissed. Due to public discontent, a special act of parliament was passed in 1916 forbidding Metropolitan from paying dividends until it improved its coaches and discharged liabilities to the injured. The company petitioned Parliament several times to remove the inability, claiming that it reduced the value of its shares and thus ability to borrow money, further hindering efforts to improve its coaches; the inability was not lifted.

A commission was issued to study the causes of the accident that remains the most deadly on the KRT to date. Recommendations of the commission include more effective signalling, tunnel lighting, less flammable coaches, gangways to permit internal movement, electric adhesion, emergency doors, and water sources in case of fire. Despite the severity of the accident, electrification of the underground network would not occur until 1928, and Metropolitan, cripped by liabilities, was unable to modify its fleet of compartment coaches until 1925.

The Syar Manor branch line was, contrary to popular imagination, abandoned due to the company's financial straits, not due to a desire to commemorate the dead. By the time the company had recovered financially, the area the branch line hoped to serve was already served by the City Line, which operated with electric locomotives. In 1953, on the 40th annversary of the disaster, a memorial stele was erected at the entry of the abandoned tunnel, listing the names of those killed. A lamp, always powered, stood next to the stele. When Syar Manor was redecorated in 1961, the stele was moved from into the station, but the lamp remains in place.

1948 collapse

On the morning of October 15, 1948, a span of the elevated Urban Crossover line between Cobble and Cobbler Lane suddenly collapsed way under the weight of the train. It was discovered that the pillar supporting it "shattered like glass", cleaning breaking into two segments. The first two coaches plunged 20 foot to the street level and left the third and fourth suspended in the air. The first two coaches, weighing 45 tons each, crushed the vehicles that stopped under it for a red light. 28 passengers were killed, and 115 injured; on the road, 8 individuals were killed, injuring 27.

The City was thoroughly mystified as to the cause of the collapse, as the line had been running without obvious problems for the last six years. A re-analysis in 1972 and testimonies from locals provided that a bomb had dropped near the faulty pillar in the Battle of Kien-k'ang in 1940, and the blast was considered to have compromised the pillar's integrity; however, the cracked pillar was hastily painted over during the city's eager reconstruction efforts in 1942, concealing the crack and signs of metal fatigue. After the incident, the city suspended the operation of the elevated lines for two weeks for a thorough inspection. In the end, 156 pillars were replaced, and the lines were tested by heavy loads in the following month before re-opening.

2003 poisoning

The millenarian Gek-luq cult conducted simultaneous sarin gas attacks on two KRT trains in December 2003, killing 39 travellers and injuring another 2,189, as well as leading to another 11 deaths and 189 injuries by stampeding. The attacks were part of the same scheme, later revealed, as the hijacking of the Twa-ts'uk-men Station on the same day. The lethal gasses were simultaneously released by cultists from inconspicuous dewars on trains near Lin-men and Sram stations respectively, at 7:00 a.m. Due to ventilation and the piston effect, the gasses permeated at least 44 stations and emerged onto street level via shafts, and casualties were exacerbated by confusion and congestion.

The toxin was not identified until a toxicologist diagnosed it from one of the most severely affected victims, and consequently the two trains containing the toxin ran for another 71 minutes after the release of the gas, before service was suspended across the network and evacuation undertaken. After a toxicology report was wired to KRT, it instructed all train drivers on nearby lines to release passengers at the nearest stop. Train drivers and station masters were instructed to broadcast that "a dangerous and deadly substance" was present in trains and stations and to urge all passengers to leave as quickly as possible; however, eleven were crushed to death in the ensuing stampede in two stations' stairwells.

The network control centre had, prior to the toxicology report, believed that the initial victims suffered "acute cardiac conditions", judging by by-standers' observations, before widespread discomfort was reported, but did not suspect the presence of a toxic agent. According to testimonies, reports of medical emergencies "trickled in" to the control centre, and it was unable to identify which trains were the source of the toxin or the extent of its distribution, leading to a general suspension of services across two lines. As nearby stations offered transfers, some victims did not report their discomfort until they had boarded a train on another line, causing confusion at the control centre.

After the attack, KRT continued to suspend services across the whole network for the remainder of the day, when trains and stations were tested for traces of the toxin. Two dewars containing it were discovered in the bellows between carriages, where they were hidden from view but poisoned those standing nearby, and a further dewar was found on the tracks. Services resumed midday on Dec. 31, but at this point Twa-ts'uk-men Station had been hijacked, preventing resumption on sections of the four lines entering it. Emergency buttons were upgraded following the attack, that the control centre would be informed of the reporting person's location.

The Ministry of Transport superintended an investigation in KRT's response to the attack and concluded that a number of its reactions may have contributed to the number of casualties. The investigation asserted that the heart of the issue was the control centre's inability to locate the source and extent of the toxin, which led responsible officers to conclude that an immediate evacuation across the entire network was the only possible recourse. The evacuation then caused panic amongst the passengers, who not only rushed through narrow exits but also collided with passengers entering the station from outside. In response, the Secretary of State for Transport, Lord Syip, and the Governor of the KRT, Mark Plet, resigned.

Culture

Ticket collection

KRT's tickets, particularly old Edmondson railway tickets, are collected by some. These tickets are rare because it was standard practice until the 90s to collect tickets from travellers at the end of the journey, and only stamped tickets can be retained as proof of payment.

Games

- Train Driver 2022 includes four lines on the KRT.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Convenience fee of 5% or 2 ma. applies, whichever the higher.

- ↑ Prior to electrification by third rail in 1927, passengers could cross tracks with the guidance of station staff.

- ↑ While the Metropolitan line was also supposed to run on coke, which did not produce smoke, the company's poor finances resulted in a degrading fuel supply that caused much pollution, and the stations, not designed for coal-burning locomotives, became infamous for their lingering smoke.