Kuchkabal Nalmoria

Kuchkabal of the Nalmerian Archipelago Kuchkabal Nalmeja | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1677–19th century | |||||||||

|

Flag | |||||||||

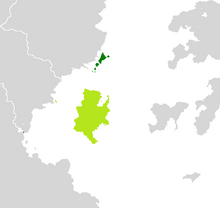

Namoria (dark green) inside the Yajawil of Barriset (light green) | |||||||||

| Capital | Nakkan / Qhor am-Sadaf | ||||||||

| Religion | White Path Azdarin | ||||||||

| Halak Winik | |||||||||

| Legislature | Nal Holpop | ||||||||

| Historical era | Mutulese Ochran | ||||||||

| 1677 | |||||||||

• Disestablished | 19th century | ||||||||

| Currency | Baat | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Kuchkabal Nalmoria was a subdivision of the Yajawil of Barriset created after the Nalmerian Archipelago was ceded to the Mutul following the devastating Ozeros War.

History

The Mutuleses first arrived in the Namorian Archipelago after the establishment of the Iifae Caliphate of Barriset. They found at first little interests in the islands, until the Ozeros War gave them a strategic importance as the natural "shield" of the Fahrani coast. By taking over Nalmoria, the Mutuleses gained greater leeway over the continental sultanate. Quickly, the Archipelago was reconverted as a forward base of the Mutuleses fleets and a source of food, repairs, and shelter.

Economy

Inland plantations cultivated various Resins and Citrus for export, and made extensive use of slave workers.

Administration

The Nalmorian elites were not replaced by the Mutuleses and kept an administrative role in the cities and their traditional communities, even as the Mutuleses merchant-aristocracy became more and more prevalent, but remained under the supervision of an Oxidentalese Halak Winik. The role of the Halak Winik was to collect taxes and to create and maintain the infrastructures necessary for trades, including roads, ports, docks, warehouses, aqueducs and cisterns.

Among the legal innovations introduced by the Mutuleses were the Code of Slavery, enshrining the rights and duties of both the slaves and their owners, and a dual legal system depending on religion. Sakbeists were judged by Mutuleses administrators and officers, and included both physical punishments and reparations to the wronged parties. Yens were judged by courts of religious scholars from the local communities, and followed traditional practices.