Uniforms of Themiclesian armed forces

This page catalogues the uniforms of Themiclesian armed forces. Early Themiclesian military bodies rarely possessed distinctive clothing, as state-issued body armour usually identified its wearer. After the obsolescence of armour, the government sometimes mandated certain emblems be used, though most soldiers and sailors had to supply their own clothes. Casaterran-style uniforms were introduced in the early 19th century, and dress uniforms since have followed Casaterran social norms. In more recent times, efforts have been made to standardize battle equipment and clothing for effectiveness and economy, though dress uniforms tend to be peculiar to the unit, more so if it had a long history or distinct role.

Terminology

Themiclesian armed forces use the same terminology as civilians to describe levels of formality in various uniform styles. Generally, there is only one uniform described as full dress applicable to any serviceperson, while there could be several half dresses and undresses. Note that this terminology strictly describes formality from a civilian perspective and does not describe how these forms of dress may be used for internal functions. In the 19th century, military uniforms switched to the Casaterran style and followed civilian standards of formality very strictly, creating little need to stipulate equivalencies between them; however, as they diverged at the start of the 20th, such stipulations were formalized.

Degrees of formality

- Court-dress (朝服, t.mru-bek): certain senior officers evolved from medieval, civil offices and thus retain the status of a member of the royal court. For these officers, it is required to wear court-dress when attending certain functions at court. These functions include state openings and prorogations of Parliament, royal audiences, birthdays, coronations, etc. The court-dress consists of a complex headgear and robe, which in modern practice is worn over a frock coat. The robe is black for public officials (as in the case of military officers) and other colours for individuals not serving at court.

- Dress (具服, kwa-bek): literally "full dress" (a chance similarity between Tyrannian and Shinasthana terms). It is equivalent to the white tie worn by civilians. Full dress in most units will include either a tailcoat, frock coat, or cutaway coat, worn with collars standing up. Many units in the 19th century recognized tailcoat as full-dress and frock coat as half-dress, but this distinction evolved with civilian fashion, and after 1850 the tailcoat became full-dress in evenings, and frock coats were promoted to full-dress for mornings. The Royal Guards, however, retain a tailcoat as full-dress even for mornings. While elaborate decorations were once common on full-dress, these became uncommon by the end of the Anglian Queen Catherine's reign (1837 – 1901). Austerity became the order of civilian wear and compelled the military to conform. Today, full dress in morning usage typically reflect the fashionable dark colours of this period, lapel pins and non-contrasting ornamentation on the waistcoat remaining acceptable.

- Undress (褻服, sngyat-bek): anything which does not categorize into the two above.

History

17th to 18th centuries

The use of identical pieces of garments was normalized in Themiclesia relatively recently, it previously being the prevailing notion that unit identity was sufficiently expressed through badges in the shapes of scarves, arm-bands, and ribbons on hats. In the civil context, the colour of one's over-robe took on some significance at the royal court: barons and royal retainers wore reds and purples, while bureaucrats wore black. But this practice did not spread to the armed forces until the 17th century and probably under Casaterran influence, when professional regiments were commanded to be dressed in distinct colours at various times. It is believed the practice originated as temporary designations in the order of battle, though reasons of economy may have the colours to become permanent.

The practice of wearing coloured coats was not universal and particular to the legion in which the regiment was placed. It should be noted that, while colours were regulated, the style or cut of the coat was not; uniformity principally arose in the interest of utility and fashion, as it had not been then though, as later it was, that morale could be encouraged via identification with badges. Casaterran-style coats became fashionable in parts of Themiclesia in the late 1600s to about 1730, when modified domestic designs influence again dominated, yet some units were certainly then outfitted in the Casaterran style. These major clothing changes were often financed by the royal treasury on the pretext of replacing attire worn on campaign but also for showing royal favour.

19th century

The awarding of clothing became obsolete in the long peace after 1796, but the colours of the regiments remained in effect. In the years following, cloth in the regiment's colour was a frequent and expected gift by commanders to their men. Precedents encouraged officers to redesignate necessities like uniforms and tools as the serviceperson's private responsibility, allowing officers to sell these articles to the servicepersons or the contracts to supply them. To create a monopolistic market for favoured manufacturers, uniform specifications were often excessively specific. Such practices created backlash during the 1840s. In 1847, officers were formally forbidden to profit in trade with "other officers and men assigned to their care", this being made grounds for cashiering.

Officers now unable to sell uniform or cloth, servicepeople would buy their clothing on the high street, a policy endorsed (and likely fortified by bribery) by tailors' guilds and merchants' associations. To avoid excessive charges, most soldiers and sailors chose to buy from each other or second-hand stores. To assist market competition, lobbyists demanded the armed forces remove "barriers to fair trade" such as excessively specific uniform regulations that were susceptible to become monopolies. In 1850, a notorious stamp duty imposed on transactions between soldiers seems to have been aimed at eliminating whatever profit skilled soldiers could have made in sourcing, making, or mending clothes for each other.

The reliance on second-hand clothing meant that fashionable new clothes gradually seeped into the soldier's wardrobe when handed to servants and sold. While there had been a large variety of clothing on the used market capable of satisfying all regiments' colours, black became the preferred and then sole correct colour for mens' coats after about 1865. Coloured coats were thus both rare and unfashionable, with A. Gro demonstrating that soldiers were quite conscious of fashion and attempted to incorporate them into uniforms whenever practical and affordable. Regiments therefore lost most of their distinctive colours by 1880. The Lord of Mik (b. 1802) remarked that in his youth, the regiments were "ablaze with colours", but in 1878 "are satisfied with their plain but personal purchases."

As it was now impractical to have coats in any colour other than black, regimental insignia shifted onto trousers, which were still worn with a variety of colours. Bold colours were translated as plaids or stripes that were particular to the regiment, but such trousers were rare at consignment stores and hence the prerogative of officers who tailored their clothes. To keep the men distinct, badges were first issued by quartermasters in 1877 and within a few years spread to all regiments. Early badges were rudimentary, often consisting of a rectangle, square, star, or circle in a given colour, and soldiers were expected to sew them onto their own coats. They reportedly found these badges convenient as they could discreetly remove them to resell the coat.

The appearance of department stores and mail-order catalogues in the 1870s influenced soldiers' sartorial expenditures. Mass-manufactured clothing in standard sizes reduced prices by as much as 35% in some cases. While this did not reduce dependence on second-hand goods, it promoted common practices and a basic quality in clothing and has been credited for fostering higher expectations of dress in society as well as the forces. To avoid collusion and abuse of power, regiments were not to specify which merchants' goods to purchase. While one might spend $28 in 1855 for a jacket (new one made to measure), this could be done for $20 in 1885; however, real wages actually decreased by about 30% between 1855 and 1875, with soldiers' salaries in tow.

In the 1890s, the trend in army uniforms turned towards utility, very likely influenced by foreign armies that fought in the era. As frock coats, which most regiments required, did not typically have external pockets, soldiers often made pockets and strung them up on their waists. These were sometimes called "lady pockets", as similar pockets were worn by contemporary women under dresses. In 1895, the War Ministry reviewed soldiers' gear and decided upon canvas backpacks for capacity and stability, compared to courier bags then in common use. The pockets were then attached to the backpack around 1898 and worn together whenever marching.

20th century

In the 19th century, most units had one uniform for all work, but a separate "field uniform" became common in the first decade of the 20th century. The field uniform was adopted in units for various causes: some negotiated with hotter summers or marshy areas where the knee-length frock coat was uncomfortable, and others desired utilitarian features like pockets, which were not available on frock coats typically bought from the second-hand market. For non-cavalry units, the field uniform was always a three- or four-button sack jacket, typically of a cheaper and coarser fabric, with external pockets, but different trousers were not typically provided. The unit insigne was applied to the sack jacket as to the frock coat. The frock coat, then, was promoted as a "dress" uniform.

At the behest of the Lord of Mik in 1916, Parliament legislated that all units were to wear drab or khaki "brownish" colours in the field, though the specific design and procurement was, as before, left to individual regiments. This rule solidified the distinction between dress and undress uniforms, as the khaki field uniform displaced the earlier dark field uniforms which many servicepeople wore in lieu of a frock coat. A khaki uniform was not considered sufficiently formal in contemporary society for regimental meals and public appearances. Additionally, the earlier dark field uniform consisted only of a jacket to replace the frock coat itself, while a completely new outfit was required by the mandatory colour.

During the Prairie War, the khaki field uniform was adopted by cavalry units, all of which retained the more conservative tailcoat as associated with horsemanship. The Prairie War was Themiclesia's first formal war in over a century, and experiences therein were influential at the War Office, though not all interpretations of them were ultimately useful.

Land forces

Themiclesian land forces started to assumed their modern structure under the Army Acts of 1921. The ordinary rule of the modern era, since the Pan-Septentrion War, is that field uniforms are co-ordinated by duties and environment, irrespective of unit. Thus, an air force crew member is likely to be wearing the same fatigues as an army soldier stationed in the same facility. There may be minor variations according to manufacturer and issuing authority, but principal characteristics are similar across the armed forces.

Consolidated Army

The Consolidated Army (䜌兵, rwan-prang) issues uniforms to regiments that do not have peculiar uniforms. Those formerly of the Capital Defence Force, South Army, and Royal Signals Corps, and many founded before 1921, continue to issue peculiar uniforms. Since then, some have conformed to the army's standard patterns, though others retain distinctive attire.

The field uniform of 1922 consisted of a drab green wool sack jacket, waistcoat, trousers, linen shirt, undershirt, drawers, braces, cravat, helmet, wool socks, and boots. This combination was particularly close to the Western University Regiment's uniforms. Branch and unit affiliation and rank were indicated through located on caps, lapels, collars, shoulders, and sleeves. While servicepersons generally found satisfactory the uniform's durability and aesthetics, many suffered heat strokes marching through the desert in the summer of 1926 and 27. Some threw off jackets and waistcoats, shocking officers who considered shirts and braces underwear. The black cravat was reviled as it "created a noose of heat around their necks" and was not lauderable. Most officers permitted soldiers to add and remove articles as the climate dictated, and this practice was sanctioned in 1929 by the War Secretary's ordinance.

The field uniform was updated for comfort and economy with conscription imposed in 1936. The sack jacket and skirt of the dress shirt shortened considerably, and the waistcoat disappeared. Extra volume in drawers and sleeves were too minimized while permitting mobility. The cravat was replaced by a drab knit tie that was nominally worn over standing collars, but most soldiers tucked them into the shirt instead. The sack jacket acquired two chest pockets, not frequently used as webbing ran directly over them; the trousers acquired four pockets, two on the side seams and two pouches over the thigh. In 1940, the wool jacket and trousers were replaced by canvas, further adressing overheating and as a substitute when Themiclesia lost much of its wool supply.

A summer variation of the 1936 uniform was issued in 1941, with shorts instead of trousers and discarding the jacket and necktie entirely. This uniform was in consideration for at least two years, but conservatives voiced concerns that it exposed too much of the body "to be decent anywhere except the most extreme heat," as much as fearing soldiers would reject it. This reservation proved specious, and the summer variation was in use year-round in Dzhungestan and Maverica, where the heat, combined with humidity, was even more formidable for Themiclesians accustomed to colder climates.

Reserve Army

(聯戲, rin-ng′ars)...

Territorial Forces

The Territorial Forces (方兵, pang-prang)...

Militias

The Militias (郡兵, qur-prang; 邦兵, prang-prang)...

As with militias, naval personnel were historically responsible their own clothing, with few regulations applied. The navy was responsible for selling the fabrics to sailors, but the rights to sell goods onboard were usually auctioned, and the winner often inflated prices with an effective monopoly. As a result, most sailors preferred to bring fabric or make purchases on port calls.

The earliest Casaterran-style naval uniforms were more similar to a dress code than uniform in the modern sense. In 1819, officers and men were ordered to dress in a blue coat, white waistcoat, and trousers; as pictorial evidence demonstrates, any blue tailcoat was acceptable, mutatis mutandi. It was acceptable to add private clothing to the ensemble, as by custom a woollen jacket was worn over the waistcoat; as this article was not formally regulated, it was used as a canvas for a crew to identify sartorially with their vessel. The naval dress code of 1819 was not amended until 1920, when illustrations were promulgated to standardize the appearance of naval costumes.

Fleet

Sailors often sought to preserve the costly overcoat and waistcoat, and it become typical to wear only the shirt and cravat on normal duty. Though this was ostensibly out of order, it was tacitly permitted. Early portraits show sailors with closed collars and neatly-tied neckcloths, but by 1830 this had become uncommon. Under Casaterran influence, neckties loosened, allowing collars to open and flap down over their shoulders.

Around 1840, commentators remarked how much of a sailors could be seen unclothed, provoking the Admiralty to require sailors to fasten their neckties and wear a frock coat when publicly engaged. This ordinance had little effect, since neckcloths grew only looser through the decade. By 1850, the neckcloth was similar in function to a scarf, and the bow was abandoned for a four-in-hand knot. It is not clear why sailors preferred this knot, but it is possible that loops on a bow was seen as a hazard with the rigging. In the 1905 uniform update, the obsolete tail coat was withdrawn for enlisted men, though officers were still expected to supply their own tail coats for formal functions.

Marines

The Admiralty's Army, which existed between 1703 and 1801 and is the source of 2 of the marine corps's 29 modern regiments, had a uniform described as "melon coloured", but it is unclear whether it was yellowish, i.e. the colour of a cantaloupe, or greenish, i.e. of a honeydew melon, because Shinasthana used the same term to identify both fruits.

The Marines other regiments' had no standard uniform coming into the 19th century, it being regulated on a regimental basis as is the case in the unreformed army. Some regiments adopted Ostlandic-style uniforms in the late 1700s, but others wore robe-style uniforms up to the 1820s. Tailcoats were widely adopted in the 1810s as they were popularized. The six regimental authorities in the Marines each adopted pecular colour combinations for their tailcoats, and in the following decade frock coats were issued in the same colours. With the ban on regimental uniform contracts coming into effect in 1847, each soldier including marines was expected to procure and maintain his own wardrobe, and this remained true until 1916.

Aerial forces

The uniforms of the Themiclesian Air Force were revolutionary in the domestic military sphere that it was an imported design. This formerly was somewhat taboo in the same way direct imitation of another nation's military precepts was in the Army Academy.

Aviators

The initial pattern of the Air Force dress uniforms was heavily influenced by the Tyrannian Royal Air Force, which showed influence from the Royal Army. It consisted a shirt with fold-down collars, necktie, trousers, suspenders, belt, Sam Browne belt, waistcoat, and overcoat, the latter two with standing, closed collars. The trousers were deep, greyish-blue with a bold indigo stripe on the sides, with a slight blouse where it tucked into boots. The waistcoat and overcoat were both "air force teal", a creamy teal colour so-called due to its ubiquity on Air Force uniforms. The collars on the overcoat were a slightly deeper hue of the same colours. Aviators wore black, knee-length boots, with the top two inches customarily folded down for tighter fit.

Sartorial editor M′rjang wrote that this forced the boot to hug the contours of the wearer's calf muscles, which created a sharper and "literally more muscular" appearance that was intentional. Some historians believed that early Air Force leaders were overidingly concerned with predatory War and Navy Ministries hoping to annex the Air Force, leading it to adopt an aggressive and impactful style that broadcasted its independence from either, whose uniforms were both characterized by following civilian fashions. The Sam Browne belt was worn by aviators, who carried pistols for self-defence; other services, ordinarily not permitted to carry weapons off duty, envied this privilege. It was also a contravention of Themiclesian social etiquette, which demanded disarmament in urban areas (邦中); this included not only weapons but their accessories, such as scabbards, holsters, pouches, and belts. Only the Gentlemen-at-Arms and high-ranking civil servants were excepted from this rule, and its extension to the Air Force was perceived as the government's vote of confidence in them.

The TAF led Themiclesian forces to adopt the blazer as a half-dress uniform, for the entire branch, in the early 20th century. While unit characteristics, decorations, and badges had all but been purged from formal dress codes to conform to civilian norms in the late 19th century, the forces in general sought to transfer their insignia onto garments in ways that would not conflict with those. The TAF, after encountering resistance against colourful dress uniforms in formal settings, started wearing blazers that were common for clubs and sports teams, for informal settings. In 1921, the TAF hosted the first inter-service sports tournament and commanded its attending officers to appear in a uniform blazer. This idea soon spread as blazers were sufficiently informal that unit insignia and decorations could be worn in full colour without stirring social condescension. In the 50s, this blazer was legitimated as a working uniform for the TAF.

Ground crew

Air infantry

Themiclesia's air force ground forces, the Themiclesian Air Force Regiment, were originally ordered to wear a blue frock coat, teal cravat, and grey chequered trousers as their dress uniforms.

Coast Guard

In 1918, the Coast Guard was formed by amalgamating the prefectural revenue marines, other maritime safety apparatūs, and certain militia units under the Home Office. However, as coast guardsmen were expected to work in uniform, pockets were added, and dress shoes were replaced with boots that could be polished to a patent finish as required. The hat was also changed for naval officers' peaked caps in the case of guardsmen at sea, or pith helmets for those on land patrols. The uniform was also the first dress uniform in Themiclesia that did not include a waistcoat.

In 1945, the Coast Guard's uniforms were overhauled to acknowledgement the (then) two branches of the service. Guardsmen of the Land Force were to wear a navy blue, wool peaked cap with a red wall, and the Coast Guard emblem in gold plate upon it; they wore trousers of the same colour, with a red gallon on the trousers. Guardsmen of the Sea Force instead wore a white peaked cap and plain white trousers instead. The navy blue tunic and white belt was shared between the two branches. In 1975, guardsmen operating aircraft formed a third branch, the Flying Service, and their caps and trousers had blue accents in place of the red of the Ground Force. As was the accepted custom, enlisted guardsmen wear their trousers tucked into boots, while officers wear them over boots.

While Home Office regulations require guardsmen wear a dress shirt and necktie under their tunics, this is not always done as such. Some Coast Guard units discourage their men from following uniform regulations to a fault, while others consider strict adherence a point of pride. As the tie is never visible with the tunic fully buttoned, many guardsmen button an easily-laundered detachable collar to the interiors of their tunics' collars, giving the illusion that a well-starched shirt is worn. Other Coast Guard officers believe that showing collar is wholly unnecessary, and that pursuits like this are contrary to the Guard's duty-oriented style that symbolizies resoluteness. However, it is generally agreed that it is never acceptable to leave buttons undone, such as the Royal Guards do.

Themes

Women's uniforms

The official role of women in the armed forces expanded in the 19th century. The Convalescence Service, set up in 1863, employed women in considerable numbers and appointed female officers on the grounds of professional knowledge as early as 1870. A sprinkling of female officers existed in other locales, but many did not discharge their offices personally, leaving it instead to a male lieutenant. The Convalescence Service did not employ military uniforms in the modern sense of the word, it being judged inappropriate for a convalescing environment, yet a standard nursing attire was used under an apron. Female officers did not usually wear a nursing attire, but ordinary daytime outfits. Some female officers in other places wore uniforms, but most did not.

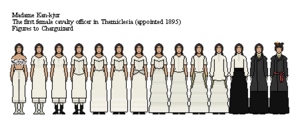

The oldest surviving set of uniforms worn by a female officer who did personally discharge office belonged to Lady Kan-kjur (1854 – 1911), a cavalry captain between 1895 and 1899. Her uniform can be described as a feminized version of that of her unit, the 410th Signals Cavalry. She wore a grey redingote and white chemisette approximating male officers' frock coats and shirts in like colours; underneath, she wore all layers typical in a daytime outfit belonging to a woman of high status.[1] While the undergarments are formally reminiscent of civilian clothing, they were specialized and ruggedized to accommodate her professional requirements. The fact that these items were in a trunk together with her uniform, and not with her other garments, also suggests she considered the undergarments part of the uniform. Similar measures are often found on uniforms belonging to other aristocratic women in the armed forces, but there also exist examples without.

There were no firm regulations over what a female officer's uniform should look like relative to that of her male peers until the Pan-Septentrion War. For enlisted female servicepersons, who found work as clerks after 1901, regulations establishing colour and cut appeared in different units the 1910s. Early designs typically included bodices approximating mens' coats but a floor-length skirt. Women were expected to conform to contemporary precepts of modesty, though these were not uniquely military requirements. Structured undergarments, like the corset, remained in use by some, if not most, female servicepersons. Enlisted women were expected to acquire undergarments privately, as most were commuted from home rather than lived at a garrison. For fear of voyeurism, female servicepersons were cautioned in 1921 against fashionably shortening their skirts, but some nevertheless did so with no great objection from above, as womens' clothing had dramatically changed since the 1890s.

The woman in military uniform became a cultural symbol of female independence in 1920s Themiclesia, as the armed forces offered stable employment and some opportunities for advancement irrespective of her origins or marriage.

Enlisted uniforms

Historians note that the vast majority of uniforms surviving from the 1800s belonded to officers, with but a minuscule number of enlisted examples, in spite their obvious numerical superiority. Several factors may have contributed to this imbalance. Officers often made new uniforms when they took new commissions and retained the older sets as mementos, and their privileged economic condition enabled them and their successors to preserve old uniforms, often unconsciously in an attic or crawlspace at a large house, for many years. In contrast, enlisted men often modified their uniforms for civilian use or sold them at discharge to a clothier, where another serviceperson might buy it, or it may be altered for civilian purchase. Uniforms worn beyond mending or selling might be cut into rags, and when even that failed, they became candlewicks or filled blankets and winter coats.

Despite the paucity of enlisted uniforms, they show salient differences from officers' uniforms, allowing historians to interpret their often-different attitudes in military employ. In an era without strict uniform regulations or those outright ignored, officers uniforms were not only newer but frequently more fashion-forward, while enlisted uniforms showed signs, with or without remodelling, from older designs. When officers' uniforms darkened according to civilian fashion in the 1870s, enlisted uniforms were often unfashionably colourful, remaining blue, red, green, and yellow; some were dyed to pursue a more fashionable colour, while officers' uniforms are almost always made in a fashionable colour. The quality of fabric and workmanship also differed dramatically between officers and enlisted rates.

Holes from repeated use suggest that enlisted soldiers used more pins, possibly to hold medals, than officers, who preferred a cleaner appearance. These differences are frequently reflected in the diaries of enlisted soldiers, one commenting about officers' omission of insignia "to appear superior". In a similar vein, a well-cut coat in a good fabric was often seen as the privilege of an officer, while the enlisted man often contended with anything that provided adequate warmth. "The fashionable, clean, and well-made coat was the badge of an officer, like it was to the middle-class man," writes historian A. Gro, "no amount of chevrons, bars, or shiny brass could displace the symbol of social superiority. There is even a letter written by a private in 1873 begging his comrade not to wear his new medal, because that exposes his 'attachments'."

Ostlandic influences

In the second half of the 18th-century, Ostlandic consultants became influential in the Themiclesian army's tactical development and, in the course of their employ, introduced certain dressing habits to some Themiclesian units. One is the leather stock, which in its most basic form is a piece of leather fastened around the wearer's neck with a buckle. According to popular understanding, an Ostlandic king invented it to keep his soldiers looking forwards and force an upright demeanour, and by the late 1700s many Casaterran armies used it. Initially, Emperor Ku ridiculed it as a "dog collars", but under his ministers' advice he nevertheless did not prevent its use in the four regiments under Ostlandic training. In 1763, officers from them were ordered staff four newly-raised regiments, also dressed in like manner.

None of these regiments survive in their original forms today. The Highlands Musketeers (山射) were merged with the City of Tups Musketeers (濧邑射) to form the Mid-Themiclesia Regiment (中辰旦族) in 1797, while two companies from the West Isthmus Footmen and Tin Mountain Grenadiers were consolidated and renamed the Ostlandic Musketeers, to survive the Admiralty cuts of 1801. The Mid-Themiclesia Regiment expanded into the 22nd Division in the Pan-Septentrion War, while the Ostlandic Musketeers remained in that form in the 11th Mechanized Battalion of the Marine Corps. With the end of state-issued uniforms in 1847, the leather stock remained as a regimental insigne, but, replaced in that function by badges around 1890, it disappeared around the turn of the century. Photography shows that the leather stock was worn not on the shirt collar directly, but over a necktie.

Controversies

Abuses

It is held by Pwa, Prut, and Bi JJ. in R. v. Mak (1975) that "by the mere public wearing of regimental or naval uniforms or of apparel that exactly resemble those (of that kind) established by statute or ordinance under statute, no offence of the kind of c. 5 Dreng 12 is committed," citing R. v. Krens (1887), a case about impersonation of judges by wearing their vestments in public, prosecuted under c. 5 Dreng 12. In that case, the judges ruled that because a judge's office is in a courtroom, the wearing of a judge's robes outside of the courtroom does not constitute an abuse of authority. Even though Pwa, Prut, and Bi JJ.'s judgement does not mention the air force or coast guard, their judgement here is believed to show that civilians may wear military uniforms of any kind legally, as long as it is not done as part of another illegal act.

The emblems of some high dignitaries, like those of the Sovereign, were protected against misappropriation. It is held to be repugnant to the supremacy of Parliament, and prosecutions are had by order from the Clerk of the Parliaments. But as far as the armed forces are concerned, only the seals of generals appointed by act of parliament fall under this protection. Inferior officers' (up to the rank of lieutenant-general and generals appointed by order-in-council) seals and other emblems were not protected this way. At any rate, this special protection was abolished by statute in 1952, and now it is not uncommon to see Themiclesians wearing plush, cartoonish versions of the imperial crown to show support for the monarchy.

The wearing of military uniforms may be part of an offence of abuse of authority, e.g. impersonating a particular officer as part of an attempt to exercise that officer's authority over those personnel assigned to them. The scope of authority has been circumscribed by case law in the 20th century. Because authority is an appurtenance to a real and particular office, there from the start exists no authority abused by symbols that suggest the existence of a fictitious office. For example, in 1967 the Court of Error and Appeal held that the invention of a fictional regiment and pretention of an office therein cannot be an abuse of authority. Yet if it is demonstrated that an intention exists to abuse authority, an offence is committed as soon as any act that "in those under said authority, creates confidence and credibility in the pretense" is performed, even if the abused authority has not been exercised.

The standard of "confidence and credibility" has been held to be rigorous by courts. Judge Nep said in 1991 that a conviction can only obtain by the jury if "the readiness to fulfil the legal duty of obedience has been created and was indeed so created by that pretense." This proviso was pertinent to the 1991 case because a person seeking instruct certain soldiers to hand over confidential documents did not create confidence and credibility specifically by means of his pretense (which included the act of wearing the uniform and appearing before those bound to obey the abused authority), but fortuitously by the instructions of a different superior officer, whose incorrect judgement was not effected by the pretense.

The wearing of military uniforms may be cited as part of an abuse of identity in the case of a member of the armed forces, e.g. by collecting the paycheque of a serviceperson by wearing their uniform, forging their seal or signature, etc. This is more generally addressed and penalized under the heading of criminal fraud. It appears as of 2020 this offence has been committed mostly by servicepeople against other servicepeople, and only one prosecution, unsuccessful, has been of civilians against servicepeople.

Though civilians may wear military uniforms nearly without restriction, it is a disciplinary (non-criminal) offence of active servicepersons in the Consolidated Army, Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard knowingly to wear a uniform with incorrect insignia, even without the intention of fraud or abuse of authority. Severer penalties are imposed if those are the ends sought and obtained by the wearing of incorrect insignia. The definition of insignia is held to be narrow and exact by both military and superior courts: a mere similarity or partial co-incidence cannot constitute this offence, as all servicepeople have a basic obligation to ascertain the orders they follow to be legitimate. Likewise, insignia here contemplates only those that convey an office and its appertaining authority, not to those that record qualifications, service history, or honours. While insignia is plural, the abuse of a single insigne satisfies an offence, since the word's plurality is an artifact of Anglian translation.

Notes

- ↑ Altogether, her outfit for meeting other officers consisted of drawers, linen shift worn against the body, stockings, garters, whalebone corset, two under-petticoats, padded bustle, over-petticoat, corset cover, chemisette, over-skirt, redingote, boots, gloves, and tricorne.