Uzeri Rebellion

| Uzeri Rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

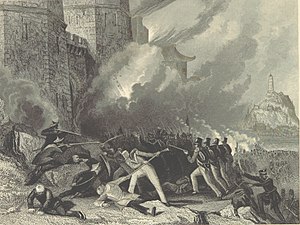

Anglian troops landing at Giju, 21 February 1824 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Uzeri rebels | Myŏn dynasty | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

General Edward Cunningham Admiral Charles Anderson Uzer Mahir I |

Janghŭng Emperor | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Expeditionary Force

Royal Navy

Uzeri rebels

|

Nine-Banner Army

Southwest Force

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Anglia

Rebels

|

Myŏn total

| ||||||

The Uzeri Rebellion, also known as the First Lakkien War of Independence and the Susanna War, was a rebellion in southwestern Menghe fought by members of the Uzeri ethnic group against forces of the Myŏn Dynasty. It broke out in 1822, when warlord Uzer Mahir organized a rebel army in the highlands of what is today the Lakkien Semi-Autonomous Province and began leading attacks on Myŏn military strongholds. Initially, the Myŏn dynasty appeared poised to crush the rebellion, but the seizure of the merchant brigatine Susanna in 1824 provoked the United Kingdom of Anglia and Lechernt to declare war on Menghe and increase support for the Uzeri rebels.

Unable to compete with state-of-the-art Anglian weaponry, Menghean land and sea forces suffered a string of humiliating defeats, culminating in the Treaty of Kee Chu in 1826. In addition to recognizing the independence of the Uzeri Sultanate, the Myŏn rulers agreed to major restrictions on the capabilities of their navy, and allowed Casaterran merchant ships limited trading rights in the cities of Giju, Sunju, and Dongchŏn. Both domestically and internationally, the swiftness of the war's conclusion shattered impressions of Menghean military strength, setting the stage for further efforts to pry open Menghe's lucrative trading market. Within the Myŏn court, it ignited a "Western Influence debate" which would shape Menghean politics for the next hundred years.

Background

Prior to 1820, the Myŏn dynasty controlled a stretch of territory similar in extent to modern-day Menghe, including a southwestern area in which Lakkiens, Argentans, and Daryz were the majority ethnic groups. This region was first integrated into Menghean rule in the 9th century BCE, and had experienced several stretches of independence since then, most recently from 1514 to 1547. In contrast to other areas, Meng cultural identity held little sway among the population, though some local elites had adopted Meng customs as a symbol of status. Previous rebellions had already shaken the area in the 18th century, though none of these spread beyond isolated rebel holdouts in the northern mountains.

Growing regional tension in the southwest took place in the context of a shifting geopolitical balance. In response to the memory of the Menghean Black Plague, which killed off at least half the country's population, emperors of the Myŏn dynasty had imposed a strict prohibition on any contact with foreigners, closing the country's ports to oceangoing trade and refusing to conduct diplomacy with Casaterran powers. Though viable in the early 16th century, when Casaterran explorers were still a small presence in the region, this stance was increasingly dangerous by 1820, as Innominada, Maverica, and much of the continent of Meridia had already been partitioned up by colonial powers.

Casaterran politicians, particularly in Anglia and Lechernt, saw Menghe as a lucrative market for exports due to its large population and reasonably healthy domestic economy. It was also the region's leading producer of silk, tea, and porcelain, which were only accessible in limited supply from Themiclesia. As the amount of uncolonized space in the New World steadily dwindled, many Casaterrans saw Menghe as a critical frontier in economic expansion, with major rewards for whomever could crack open its closed market.

Domestic origins

Uzer's uprising

The Uzeri Rebellion began in 1822, when a Taleyan religious leader named Uzer Mahir began amassing a rebel army in what is today the northern edge of the Lakkien Semi-Autonomous Province. Initially relying on bandits and bands of outcasts already hiding in the mountains, he soon became strong enough to draw volunteers from the general population, and in September of that year he led his forces against the outpost city at Hasavyurt and quickly overran its defenses. Hardly pausing to consolidate his gains, he proclaimed himself Sultan Mahir I, gathered more troops from the city population, and led his main force south, besieging the regional capital at Quảng Phả.

Menghean reaction

Myŏn officials fleeing the fighting carried news of Uzer's actions to the Menghean capital at Junggyŏng, where the Janghŭng Emperor ordered a punitive expedition to suppress the rebels and restore central control. One army, under the command of Duke Mun, would gather at Hyŏnju and march on Quảng Phả to put pressure on the rebels and eliminate their base of operations. A second, under the command of Duke Chŭng, would gather at Namwi (today Pyŏng'an) and march on Quảng Phả to relieve the siege. As in previous anti-rebel actions, the Myŏn leaders hoped to use an overwhelming display of force to retake lost territory and break Uzeri morale in a swift and decisive operation.

Lengthy delays in gathering and mobilizing the necessary forces, however, soon upset this plan. Decades of embezzlement had drained the military's treasuries, and regional commanders were reluctant to contribute "their" troops to the operation. Quảng Phả's beleaguered defenders surrendered in April of 1823, before Duke Chŭng's army had even departed from Namwi, a profound embarrassment given the Emperor's proclamation that the city would be relieved. Worse still, other sympathetic rebels had risen up in other southwestern cities, spreading across the countryside to patch together a fragile Uzeri Sultanate with Mahir I as its putative monarch.

Foreign arms shipments

Initially, Sultan Mahir I saw no reason to change the isolation policy, which served his needs as well as it had served Menghe's. Consolidating control over some 350,000 square kilometers of territory was his main priority, followed by organizing a reliable defense to keep out the looming Myŏn intervention. Anglian diplomats made the first move, sailing a warship into Quảng Phả harbor and signaling via flags that they wished to initiate talks. Not understanding the signals, bands of rebels in fishing boats initially rushed after the ship to chase it off, but on the third attempt to enter the harbor a translator was able to make their intentions clear and they were given an audience with the newly-crowned Sultan.

Playing to Mahir I's fears about the coming intervention, the Anglian emissaries promised a steady supply of modern weapons to help support the Sultan's nascent army. In return, they asked that he allow Anglian-flagged trade ships free access to ports in his new kingdom, at all times of the year. Inexperienced at statecraft and concerned mainly with defense at this point, the Sultan enthusiastically agreed, especially after a cannon from the warship was brought ashore and fired as a demonstration.

In the months that followed, Anglian trade ships made regular voyages from Khalistan to the Uzeri Sultanate, bringing state-of-the-art field guns and flintlock rifles. Anglian army staff were also brought ashore to train Uzeri troops in the use of the new weapons, including large-formation volley-fire drills. Given the haste with which the rebels had thrown together their forces, and their lack of prior expertise in strategy, the resulting army was rather disorganized by Casaterran standards, but still much stronger than Myŏn commanders had anticipated.

The effectiveness of the new weaponry became clear in the autumn of 1843, when Duke Mun led his army toward Hasavyurt. Two attacks on the city walls were driven back by accurate rifle fire from the ramparts, forcing the Duke to withdraw upriver and wait out for reinforcements in a walled encampment. Even as he delayed the offensive, his scouts and supply lines came under persistent fire from rifle-armed skirmishers, who effectively waged guerilla warfare in the northern region around Dài Nióng. Duke Chŭng encountered stiffer resistance in his own westward drive in December, confronting cannon-armed rebels in the foothills around Hồng Xuyén and suffering heavy losses. Menghean morale, already eroded by the long delays in mobilization, seemed at risk of collapse, while Uzeri soldiers grew more and more enthusiastic about their battlefield successes.

Foreign involvement

The Susanna Incident

After word reached Junggyŏng that Uzeri rebels were armed with Casaterran rifles and cannons, the Janghŭng Emperor ordered the Namhae Fleet to enforce a blockade south of the Uzeri Sultanate and prevent any foreign aid from entering the country. As Menghe still lacked formal diplomatic relations with Casaterran countries, news of the planned blockade did not spread very far, nor were any specific provisions made for ships under neutral flags. The content of the blockade proclamation, which reflected Menghe's prior status as a regional hegemon, was significantly out of step with contemporary diplomatic procedure.

The critical spark came on March 9th, 1823, when a Menghean war junk intercepted the Anglian brigatine Susanna off the southwest coast. After they searched the ship and found crates of Baker rifles and gunpowder, they set fire to the ship and took her twenty-six crew members aboard as prisoners. After being carried back to Giju, the prisoners were brought before the local magistrate, who pronounced that they were guilty of violating the prohibition on entry by foreigners and of conspiring to arm rebels against the Emperor. As both were crimes of the highest degree, the captain and first mate were sentenced to death by a thousand cuts for organizing the shipment, and the remaining crew members were beheaded for serving as accomplices. A proclamation describing their fate was passed on to rebel forces in the hopes of dissuading further arms smuggling.

News of the Susanna's fate spread like wildfire once it reached Hadaway. Anglian newspapers printed vivid, if speculative, illustrations of the execution, drawing on existing racial tropes to cast Mengheans as savages and barbarians. Under public pressure to respond, Parliament issued a proclamation of war, authorizing the Royal Navy to proceed to Menghe and conduct a punitive operation if reparations were not granted immediately.

General Edward Cunningham, Duke of Westminster, commanded the expeditionary land forces, which consisted of the 51st Royal Anglian Fusilier Regiment, Princess Anna's Royal Fusiliers, and the 1st Kings Dragoon Guard Regiment. Logistics and support troops would be drawn from Anglian-occupied areas of Khalistan. In total, the force totaled about 1,800 riflemen and 600 cavalrymen. Admiral Charles Anderson led the naval contingent, which included 900 marines to attack forts and coastal settlements.

During the months that followed, the Royal Navy gathered its troops and ships in Portcullia. The invasion force set off in early August 1823, making a course for Quảng Phả, where they were welcomed by Sultan Mahir I. By this time, Duke Chŭng was already leading his forces toward the rebel capital, and Duke Mun had redirected his forces northward to retake Dài Nióng, which had fallen to rebels in the meantime.

After unloading the land force and taking on supplies, Admiral Anderson led his fleet eastward along the Uzeri coast, seeking to roll back the Menghean blockade. Having received word that the Anglian fleet was moving, the Menghean naval force in the area, led by Pyŏn Dong-gŭn, gathered together an advance guard to attack it. A shadow of its oceangoing strength during the Yi dynasty, the Menghean Navy lagged far behind in firepower by the 19th century; its largest war junks carried eight cannons per side in a single deck, and these were bronze pieces of roughly 8-pounder caliber. The Royal Navy's expeditionary force, by contrast, included four ships of the line carrying dozens of 32-pounder guns.

On the morning of August 24th, the two fleets made contact off Sơn Hái Point. Lacking information on the enemy ships' capabilities, Pyŏn gathered his sixteen war junks and pressed forward in a wedge formation, hoping to split the enemy's line and commence boarding action. The Anglian line of battle hit the attackers with a fierce barrage of cannon fire as they approached. Realizing too late how seriously he was outgunned, Pyŏn Dong-gŭn ordered a retreat, but in the chaos of battle the command did not reach all ships in his group. The strong wind and current which had initially supported his attack now worked against him, continuing to push his warships toward the enemy line even as some of them struggled to come about. Only two light junks managed to disengage from the battle; of the remainder, nine were sunk and six were captured with serious damage. Pyŏn's body was found among the floating wreckage.

As news from the two surviving ships spread, Duke So, the Admiral of the Namhae Fleet, ordered all remaining ships south of the Uzeri coast to regroup at Namwi. With the blockade lifted, the regular flow of arms into Uzeri ports resumed.

Battle of Làng Mới

Unfazed by news of the defeat at sea, Duke Chŭng continued to lead his main force southwest toward Quảng Phả. He still had some 14,000 men under his command, but had suffered skirmishing attacks on his flanks as he pushed through the highlands and forests north of the city, wearing down morale. Fewer than 1,000 of his soldiers carried firearms, and these were smoothbore matchlocks with less than half the effective range of the Anglian Baker rifle. The rest carried spears or swords, as it was expected that the rebels would have nothing more advanced.

General Cunnigham set up his forces in a clear, level area near the village of Làng Mới on September 19th, hoping to head off the Menghean advance as it descended from the highlands. The 52st Fusiliers formed the center of his formation, with freshly trained Uzeri riflemen forming the flanks and the Dragoon squadron held in reserve. About half a dozen 24-pounder cannon teams were dispersed along the rear of the formation on higher ground.

Seeing that he had the advantage in numbers, Duke Chŭng decided to press the attack, but his forces came under cannon fire while they were still assembling some 800 yards away. Caught off guard by the range and destructive power of the Anglian-made artillery, Chŭng issued an attack order before the force was finished regrouping, resulting in a hasty and disorganized charge toward the Anglian and rebel lines. As soon as they entered range, the Myŏn troops came under a withering and accurate crossfire, driving back the first wave of troops even as the second approached behind them. The Menghean right flank, supported by lancers, made contact with the Uzeri rifle unit on the side, but took heavy losses on the approach and soon came under fire from the rest of the formation. Anglian records describe two subsequent rushes by Menghean troops at the center of the line, neither of which made contact with the fusiliers, though the latter did suffer some casualties from crossbow volley fire.

Seeing that the Menghean attackers were wavering, General Cunningham ordered the 1st Kings Dragoons to lead a charge in support of the Uzeri left flank, which was still in hand-to-hand combat. The unexpected arrival of the Dragoons, whose approach had been shielded by smoke from the battle line, shattered the Menghean troops, who began to pull back. Chŭng signaled for his right flank to retreat, but this was interpreted as a general retreat, and the main bulk of his force began pulling back in a disorganized rout. Unable to rally his retreating forces for another attack, Duke Chŭng issued orders to regroup at the entrance to the pass and withdraw from rebel-held territory.

Fall of Fort Namdo and Battle of Baekyong Gulf

With the Myŏn force in retreat, General Cunningham and the joint Uzeri-Anglian force advanced behind them, making their way toward Namwi. Two smaller skirmishes followed during the pursuit, both ending in victory for the rebel side. Duke Mun's force, worn out by guerilla attacks and unable to reach Dài Nióng, turned about and withdrew as well.

After briefly returning to Quảng Phả to take on provisions, the naval squadron under Admiral Anderson cut ahead to the Baekyong Gulf southeast of Namwi, setting up a blockade across the broad inlet to prevent Menghean supplies and reinforcements from arriving by sea. This blockade had the double effect of trapping the Namhae Fleet under Duke So inside Namwi's harbor, where they waited out further orders.

In late November, the rebels and Anglians reached the Wŏl River and laid siege to Fort Namdo, which stood on the southern edge of the river mouth. Namwi itself lay on the far side of the river, but if the fort were to fall, Anglian cannons would be able to move within range of its docks. Even from their positions further inland, Anglian-made cannons outranged any defensive weapons on the Menghean side, allowing the attackers to bombard the city's fortifications with impunity.

Fearing that his fleet would be destroyed if the fort fell, Admiral So decided on December 17th to sortie from the city and attempt to run the gauntlet past Anderson's blockade to reach the South Menghe Sea. From there, he would sail to Dongchŏn and prepare to defend the wealthy port cities of the Rogang delta area. Well aware of Anglian naval superiority by this time, So was better prepared than his lieutenant at Sơn Hái Point, but the gap between forces remained severe. The Myŏn naval force was numerically larger, with over three times as many vessels, but its largest ship had only twenty cannons, again made of bronze and smaller in caliber than the Anglian guns. Hoping to balance the odds against him, Admiral So had several of his vessels converted to fire ships, packing their hulls with gunpowder and brushing their decks with oil. With a favorable wind and tide pushing his force ahead, he hoped to break the Anglian formation and quickly sail to open water, proceeding to Giju a short distance up the coast.

Ill fortune beset Admiral So's force from the moment it left port. Two of the ships, both crewed by survivors from Sơn Hái Point, broke formation as soon as they passed Kimmun Island, racing north to the Menghean shore. As the rest of So's sailors watched, the two junks beached themselves off the coast, their crews swimming the rest of the distance to shore and running inland. Rather than pursue the deserters, So ordered his remaining ships to press onward.

After a forward sloop brought news of the attempted breakthrough, Admiral Charles Anderson split his heaviest ships into two battle lines, which diverged to either side of the approaching enemy. Caught in a crossfire from both sides, the densely packed war junks suffered heavy losses, and could not maneuver to bring their cannons to bear without scattering the formation or colliding. Chaos erupted early on as one of the fire ships exploded in the midst of the formation, apparently after being struck by a cannonball, and proceeded to throw burning debris over the rest of the fleet. Admiral So issued the order to continue pressing onward and pass between the sides of the enemy pincer, but his drum-based commands were drowned out in the noise and smoke.

By the time the battle ended, the Namhae Fleet had been almost entirely destroyed, save for a handful of ships which retreated back to Namwi. Admiral So was captured from a lifeboat amidst the wreckage and taken prisoner, as were many other Menghean sailors. The Royal Navy had only one ship put out of action - the frigate HMS Osprey, which was struck by a fire ship and set ablaze on her bow - but the crew managed to put out the fires before they could spread to the magazine room, and the Osprey managed to return to Quảng Phả under power from her mainmast only and undergo repairs.

The loss of the Namhae Fleet, which took place within view and earshot of Fort Namdo, struck a severe blow to morale. Later on the same day, the leader of the garrison opened the gates and rode out to offer a surrender. Having occupied the fort, the Anglians moved their cannons onto its ramparts and began a sporadic bombardment of Namwi's docks, shattering the remaining trade ships and war junks there. As the monsoon dry season had already been underway for a month, fires from the docks spread quickly among wooden buildings in the city, causing serious damage.

Port raids

After returning to Quảng Phả to take on supplies, Admiral Anderson sailed to Giju, where the crew of the Susanna had been imprisoned and executed. The city's forts had been badly neglected, and were in serious disrepair; by some accounts, only one arsenal had a stockpile of matchlocks, and it had no remaining cord for fuses. After a two days of fighting (February 21st-22nd), the Anglians captured the city's forts and coastal batteries and received a surrender from the city government. The magistrate who ordered the execution of the Susanna crew was taken prisoner and placed in an iron cage on the flagship's deck, and later moved to a cell in the brig.

Concerned about a counterattack, and aware that the remains of the local forts were indefensible over the inland approaches, Anderson paraded his troops through Giju one last time before setting sail for the nearby city of Sunju. While en route, he noted in his journal the strategic importance of the (virtually undefended) Koh-eun peninsula, which Sylva would later annex as Altagracia.

Sunju's defenses were even weaker than Giju's, consisting only of a series of small forts and watchtowers strung along the Rogang estuary. Not sure if a larger naval force lurked upstream, Anderson proceeded cautiously upriver, seizing the coastal forts one by one over the course of several days. On March 8th, his fleet reached the docks of Sunju itself, and found the city nearly undefended - the small local garrison had apparently deserted their posts. An expedition sent ashore to seize supplies on the 11th quickly degenerated into unrestrained looting, followed by sporadic street fighting as local militias rose up against the small marine force on shore. As at Namwi, fighting on the night of the 12th started a series of fires in the still-dry city, and the marines on shore withdrew under the cover of the smoke. As he departed the docks, Admiral Anderson ordered his ships to open fire on the anchored trade and fishing junks along the coast as a way of denying them to any pursuing force. He retained his hold on the Rogang's coastal forts, however, and brought in reinforcements from the 51st Royal Anglian Fusilier Regiment to defend them in the event of an inland attack. Having thus set up a blockade across the main branch of the Rogang River, a vital trade conduit for southern Menghe, Anderson regrouped with his main force and set sail for the river's eastern mouth at Dongchŏn.

Unlike Giju and Sunju, Dongchŏn boasted impressive fortifications, including a 10-meter-thick wall running around the central area of the city. These defenses had been comprehensively refurbished eight years prior, ironically as a mostly cosmetic misuse of funds allocated to naval construction, and the faces of the walls were paved over in heavy stones joined by mortar. The defenders also had a reasonably large stockpile of firearms, though as in the southwest they were smoothbore matchlocks which lacked the range of the Anglian rifles.

Anglian warships arrived outside the city on the evening of March 22nd. They were immediately met by a force of war junks, including fire ships, which attempted to sneak close under the cover of darkness but were spotted by a sentry and fired upon. The bulk of the force managed to slip away upstream, as the fire ships drifted south under the river's current and forced the Anglians to break their formation. The following day, after it became clear that no second naval attack was coming, Anderson landed marines along the shore south of the city. He proceeded with the rest of his force to cautiously sail upriver, bombarding coastal positions from outside the range of their light bronze cannons.

Dongchŏn proved to be the most difficult battle for the Anglian landing force, and the most costly. The garrison at the colossal south-facing Yŏnghwa Gate, led by Wu Man-sŏk, held out against repeated assaults, earning a place in Menghean political history as a symbol of resistance against Imperialism. Off the shore, Menghean warships commanded by Jang Sŏn-yŏng made repeated counterattacks against the approaching Anglian force, even requisitioning river barges for use as drifting fire ships. It was here that the Royal Navy lost its only vessel, the sloop-of-war HMS Sparrow, which was boarded at night by soldiers who had drifted close on rafts and scuttled by the side of the river as a warning. By March 26th, however, the west-facing Pyŏng'an Gate was breached, and Royal Marines were able to disembark at the docks and move into the city. Menghean soldiers in the city's narrow streets continued to resist, but with the loss of the wall, morale finally began to crumble. The last holdouts at the Yŏnghwa Gate surrendered on the morning of the 29th, having already run out of food and ammunition, and the city was declared secure. Impressed with the tenacity of the defenders, Charles Anderson went to the gate to meet the commander of the garrison, but Wu Man-sŏk did not come forth - he had committed suicide upon receiving the invitation, after telling his subordinates that he would rather die than stand before the barbarians who had bested him. His remains were cremated using wood from the gate's collapsed roof, and enshrined in the Temple to the City God.

Standoff and negotiations

With the coastal fortifications at Sunju and Dongchŏn under their control, the Anglians were able to stop all boat traffic in and out of the Rogang, Ŭmgang, and Ryanggang rivers, bringing most of the once-thriving commerce in Southern Menghe to a halt. As March gave way to April, the first round of annual monsoon rains began washing over the southern coast, prompting Anderson to keep his fleet at Dongchŏn rather than risk sailing out into stormy weather.

Despite Anglian concerns that a large counterattack was imminent, the situation on the south coast remained at a stalemate. The still-intact Donghae Fleet, based further eastward, refused to set sail for Dongchŏn, its commander asserting that the southern ports were not his area of responsibility and blaming the loss on the poor performance of the Southern Fleet. Meanwhile on land, the Myŏn dynasty struggled to put together a large ground force, as local commanders dragged their feet in handing over troops and new recruits declined to sign up. Rumors about "man-eating sea barbarians" were already washing through the country, sending shockwaves through garrisons even in the far north. More fundamentally, the Myŏn treasury, long drained by embezzlement and tax hoarding, was already running empty from the costs of attempting to finance the war, and with the collapse of Southern Triangle commerce revenues were at an all-time low.

Treaty of Kee Chu

After it became clear that they could not triumph over Anglian forces, Myŏn officials agreed to a concessionary peace on June 14th. The treaty negotiations were held in the city of Giju, then Romanized as Kee Chu, and amounted to a listing of Anglian demands. In no position to resume the war, Myŏn emissaries were forced to accept the first of several "unequal treaties" opening Menghe to trade but curtailing its sovereignty.

Under the terms of the treaty, the Myŏn Emperor would formally recognize the Uzeri Sultanate as an independent state with its eastern border defined by the Hyangpo River, and relinquish all claims to retaking that area. Menghe would also grant limited trade access at the three southern ports of Giju (Kee Chu), Sunju (Soon Chu), and Dongchŏn (Tong Tsun), allowing ten Anglian ships to visit each port over the course of a given year and purchase goods freely from local traders. To avoid further miscommunications, Menghe would also establish formal diplomatic relations with Anglia and Lechernt, Sylva, Sieuxerr, and other major Casaterran trading powers, through the opening of consulates in the three trade cities.

Other provisions were more restrictive. Menghean warships were forbidden from traveling more than 10 nautical miles (or 38 Ri) from Menghean territory on land, and could not sail along the coast of the Uzeri Sultanate or any other country. As the Namhae Fleet had already suffered grave losses, and as palace politics had pointed to overzealous captains as the cause of the lost war, the Myŏn negotiators had little choice but to agree. Another provision, drawn up in response to the execution of the Susanna's crew, granted special judicial status to foreigners in Menghe: any citizen of a Casaterran country found guilty of committing a crime in Menghean territory or within Menghean territorial waters would be extradited to their home country for trial and punishment.

Legacy

The Treaty of Kee Chu was a critical event in Menghe's relations with the rest of the world. Trade between Menghe and the major Casaterran powers increased from a small, illicit trickle to a steady (if still constrained) flow, with large Anglian trade ships hauling heavy cargoes of silk, tea, and porcelain out of the treaty ports. When Casaterran wool and iron met with little demand in Menghean markets, Anglian merchants turned to the practice of cultivating poppies in Khalistan and selling opium in Menghe, leading to a rise in opium addiction in the southern regions.

Far from satisfying interest in the Far East, the partial opening in trade only deepened the Casaterran appetite for Oriental luxuries. A "porcelain frenzy" swept through the Casaterran nobility, and even among the general public tea drinking continued to climb in popularity. Anglia and Lechernt's effective monopoly on the Menghean luxury trade supported its hegemony over 19th-century maritime commerce, but also fueled jealousy among rival merchant powers, who sought to forge their own inroads and compete for control of the lucrative trade flows.

Within Menghe itself, the effects of the treaty were felt even harder. The decisiveness of the defeat and the clear one-sidedness of the concessions that followed came as a shock to officials accustomed to viewing Menghe as the world center of civilization, technology, and political authority, and spawned a contentious palace debate about how to respond. A reformist faction advocated for the study Western medicine, science, and technology in order to modernize the country, while a conservative faction argued that Menghe should limit foreign influence at all costs in order to prevent the decay of Menghean morals and culture. The interpretation of a treaty prohibition on the importing of Casaterran weapons became the lynchpin of debates on whether to train a Western-equipped army unit.

In the early 1830s, anti-Western anger escalated into a series of assassination attempts against Anglian traders and sailors, particularly in the city of Dongchŏn. Fearful of igniting another conflict, the Myŏn government agreed to set up "Western districts" in the three trade cities, promising additional security within their boundaries but prohibiting Casaterrans from venturing beyond their boundaries except on official diplomatic business. After two more murders within these districts, the Myŏn leadership signed a deeply unpopular agreement in 1835 granting Anglian guards and soldiers responsibility for the protection of their nationals within these areas. Meanwhile, rats coming ashore from trade ships led to a spike in localized disease outbreaks, stirring conservative isolationists' fears that a second plague epidemic could wash over the country. As tensions between Meng conservatives and foreigners continued to rise, and efforts to modernize the Myŏn military failed to gain traction, the stage was set for a second confrontation with Sylva in 1851.