Yajawil of Kehkal

Yajawil of Kehkal Yajawil Kehkal | |

|---|---|

| Motto: I am you, you are me | |

| Anthem: From your sea I shall emerge | |

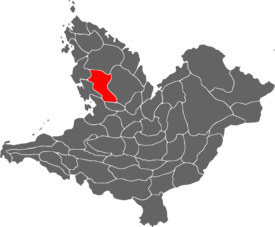

Location of the Yajawil in Mutul | |

| Capital and | Tiak |

| Official languages | Mutli Ket'an Etaan |

| Ethnic groups (2016) | Kehach |

| Demonym(s) | Kehach |

| Government | Absolute monarchy |

• K'eh Yajaw | Chel Tz'on Sip |

| Legislature | Tz'onch'ob |

| K'axpop | |

| K'axch'ob | |

| Province of the Mutul | |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | 800,000 |

• 2016 census | 790,911 |

The Yajawil of Kehkal is a landlocked province of the Mutul located art the heart of the Xuman Peninsula. It's the third largest province of the geographic region, and the second least populated. It's surrounded by the Yajawil of Mekuzb'e to the north, Nohixil to the east, Lakam Tun to the south, Yokok'ab to the south-west, Chakan to the west, and Kanayin to the north-west. It's capital and largest settlement is Tiak.

Kehkal location and remoteness isolate it from the main axis of communication of the Divine Kingdom, making it one of the poorer Yajawil nationwide.

Etymology

Kehach is the name by which the local populations identified themselves to others since the days of the Second Ytza Kingdom. It is derivated from the word Keh, meaning "Deer", and the suffix -ach which is generally used to denote abundance. When all Kehach towns and territories were gathered into a single Yajawil during the 19th century, this new territory was given a name relating to its people, but in Mutli: Kehkal, "Land of deers".

Geography

Kehkal consisted of a region of low hills with wide valleys that form swamplands during the rainy season, the region is also characterised by a number of small lakes, such as Lake Mokutun, Lake t'etek and Chann'ab. It lays at the border between the western coast (represented by the Yajawils of Chakan and Kanayin) and the K'ah Basin that occupy two-thirds of the Yajawil of Nohixil.

History

Classical Era

It is generally understood that the Kehach and the Ytze share a common ancestry. During the Paol'lunyu and Chaan Dynasties, the Kehach were located outside of the Mutul proper, being part instead of the Ytze Kingdom that laid on the Divine Kingdom's northern border. The lands of modern Kehkal were then part of the "Western Principality" of the Ytze First Kingdom, one of its four "sub-kingdom". The Western Principality represented a large sway of lands which, at the height of the Ytze expansion, went from their capital of K'ah to the east, to the shores of the Makrian Ocean to the west after the integration of what is today the modern Yajawil of Kanayin.

In AD 78, the Chaan Mutul defeated the Ytze, destroyed their capital in a Star War and forced its ancient inhabitants to flee northward. The part of the Western Principality located in the K'ah Basin was affected by this defeat and integrated to the Mutul just like the other core regions of the now-defunct Kingdom. It's less populated fringes, with their hills and swamps, would remain unconquerred by the Divine Kingdom but devolved into a collection of opposing tribes and small city-states. The Ytze rule over the coastal territories would not last much longer as in AD 80, as the Yok'ot'an population of the area revolted and founded the state of Tamaktun.

Between AD 80 and AD 110, the city-states in modern days southrn Kehkal would also be conquered by the state of Lakam Tun affiliated with the Mutul. Beyond the urban population of the state, most of its inhabitants were semi-nomads hunter-farmers, the majority of whom moved north to settle the barely inhabited forests and swamps now that the Ytze threat had been removed. Despite the formation of a short-lived league to stop this colonization, the last remnants of the Western Principality only encompassed the seasonal swamps and forests of northern Kehkal. It's during that time that the city of Tiak first appear as a leading power among the remaining settlements of the area.

Second Ytze Kingdom

In AD 250, the Mutul crumbled into anarchy and civil war. A situation that would last for the next 54 years until the K'uy Dynasty conquered most of the old Chaan territories. Both Tiak, its vassals, and its southern K'ol rival of Lakam Tun were spared by this conquest. Shortly after however, in AD 370, the Xib Dynasty of the Second Ytze Kingdom, re-conquered most of the old core region of their ethnies and rebuilt the old capital of K'ah. However, the Xib Dynasty had allied itself with the K'ol speaking principalities and tribes of the region to facilitate their conquest and presenting themselves as "liberators". As a result even after they raised Tiak and its dependencies to the rank of Province under the name of Yaxunkal, the Ytze K'uhul Ajaw refused to support any attempt they would make against Lakam Tun or to restore the old Western Principality. When, at the demand of Lakam Tun, the Ytze even moved militarily against their vassals to protect Lakam Tun, Yaxunkal revolted against the new Ytze Kingdom and seceded. Despite their superior military and victories on the battlefield, the Ka Ytze proved incapable of actually occupying the region because of logistical difficulties aggravated by the asymetric warfare practiced by the rebels which, for the first time, were called "Kehach".

K'uy Dynasty

In AD 440, the Kehach are mentioned among the auxilliaries and local allies of Kukulkan, the K'uy general who would conquer the Ka Ytze Kingdom and then the entire Xuman Peninsula. For their support, the Kehach were granted most of the old Western Principality to rule as the Yajawil of Yaxunkal, turning the tide of their centuries old rivalry with the K'ol. Despite this growth in size and status, the Kehach territories would remain at the periphery of the Mutul's trade routes and axis of circulation, greatly slowing its development and reducing its importance in kingdom-wide politics.

During the Cousins War, Yaxunkal would be in the unfortunate position to serve as a buffer state between the Xuman and K'ol Mutals. When the K'iche conquered the region, Yaxunkal lost its status of Yajawil only to be divided into a number of Kuchkabalob and grants entrusted to K'iche administrators. Their main problem was to reign in the conflicts between the Kehach and the K'ol as their opposition had only grown during the Cousins War has each ethnies ended up supporting opposing sides in their almost entirety.

Ilok'tab Dynasty

In 1318, the capital was transferred from K'umarkaj to K'alak Muul. In the process, the Xuman Yajawil was separated into a number of new Provinces. Yaxunkal was merged with the other Kuchkabals of the K'ah Basin to form a Yajawil of K'ahamil. To face the growing demand for foodstuff from urban settlements all around the K'iche Divine Kingdom, K'ah administrators ordered and financed landscaping projects all around modern Kehkal to exploit the local seasonal swamps and forests. A century later, these regions were net exporters of foodstuff, rare wood, and pelts. Large-scale chocolate exploitations even appeared during this period of economic growth, led by temples and other religious institutions who invested heavily into the area. By the 17th century, chocolate would be the main source of revenues for the Yajawil as an export to the Mutulese Ochran and the Vespanian Circuit.

Yaxunkal would remain part of the K'ah Yajawil for the next five centuries, but because of its remoteness and isolation it retained a distinct culture from the rest of the Province. With the exception of a few settlements like Tiak, urban agglomerations remained a rarity in the region which kept an essentially rural character. The regional aristocracy would continue to rule from hilltop-fortresses dominating large sway of seasonal swamps and forests exploited for their ressources. Villages were also built on top of these low elevations that kept them away from the more swampy grounds. These were used instead to create farmlands, the infrastructure required being financed by either cooperative of farmers, local noble lineages, or religious institutions. With time, the importance of the warrior-noble, and their wealth, decreased greatly and their castles fell into disrepair and ruin. In their stead, its the White Path temples and sanctuaries who grew until becoming the proeminent forces in local politics and economy, something the Halak Winik of Tiak had to compose with despite their control over the local marketplaces.

19th Century

During the Sajal War, both the K'ol and the Kehach rebelled against the new Noble Republic, with the support of the Clergy which had remained mostly loyal to the K'uhul Ajaw. For a few month they threatened the city of K'ah, but were quickly repelled and their main temples purged from their royalists elements. Pockets of resistance would remain for the entirety of the war.

After the victory of the Royalists forces, the regent Itzamnaaj B'alam divided the Yajawil of K'ahamil into three new Provinces. To the leaders of the Kehach resistance, he granted the new Yajawil of K'ehkal which represented more or less the old Kuchkabal of Yaxunkal but with new added territories so that the Province would comprise almost all wards where the Kechache were the majority of the population.

Despite this newfound autonomy, the reconstruction of the Province in the aftermath of the civil war proved complicated. Most of the investments were made into agriculture: cocoa,cotton,tobacco,rubber, and tear became the main cash crops of the region and the economy of Kehk'al became geared toward their exportation to the rest of the country. Manufactured products had to be imported from either the industrial centers in K'ah or from the portuary cities of Chakan. To support the growth of exchange, investments were made in the construction of new infrastructures. Nonetheless, the train first arrived in Tiak rather late, in 1866.

20th century

During the Eastern Wind that followed the two Belfro-Mutuleses wars, Kehkal was shaken multiple time by protests and riots against the policies of the Orientalists government in K'alak Muul. Tensions rose around the privatization of many temples agricultural lands, as well as a policy of consolidation of lands that were owned by local Wards into large exploitations. While in the south of the Province and in Tiak, the Orientalists remained in power through the support of the local populations which were essentially dependent economically on the extraction of Kaolinite, Limestone, and the mining industry as a whole which was unaffected by the Orientalists reforms. Similarily, owners of and workers in intensive poultry, deer, and snail farms remained supportive of the Orientalists reforms. But in the north, the Orientalists were unable to repress the opposition movements because of the strong supports they enjoyed from the population.

Politically, three concurring phenomenon organized the protests: popular religious figures known as Chilanob or Oracles which exorted the rural population to resist, the protestations of the local administrators to their political Patrons as they were the traditionaly given the responsability of managing their Nalil' agriculture and saw much of their powers reduced, and finally the Mam, the Elders elected to various representative roles by their Municipalities and lobbyied at the regional and even national level against the reforms. By the 40s, the situation had degenerated and led to the death of many protesters, rioters, and police officers. The botched assassination of K'uch B'alam, a venerated Kehach Oracle, led to weeks of deadly riots and tensions and provoked a national scandal, strengthening the Traditionalist and religious resistance against the Orientalists.

During the Sunrise, Kehkal violence would be quickly focused and controlled by the local administrators and religious figures against the Yajaw and his closest friends and relations, many of which were arrested and a few even killed by mobs of rioters. Kehkal was in many way an exception during that period of the Mutul' history, as the Sunrise was the conclusion of years of opposition to the Orientalists and represented a few weeks of extreme, but controlled, violence with no real follow-up. A real contrast to Provinces like Yokok'ab where violences would continue, unchecked, for a year.

Nowhere was the Cohabitation between the Occidentalists and Traditionalists factions better incarnated than in Kehkal. There, farmers and agricultors had already proved to be strongly attached to both their Oracles and other figures of "popular religion" incarnated by the most fundamentalists elements of the Traditionalists, but also to the structure of rural society based around Agricultural cooperatives, with at its core the "technician farmer" educated in the latest practices in Agronomy. As a result, the Cohabitation Government naturally chose Kehkal as the testing ground and posterchild of their agricultural and educational reforms, known as the First Green Revolution in the Mutul, which was received with enthusiasm by the Kechache.

With such strong grassroot support coupled to the investments from the top, the First Green Revolution in Kehkal was a success mediatized thorough the Divine Kingdom, strenghtening the credibility of the Cohabitation Government. This image of a perfect fusion between a traditional society and modern practices was so strong, the Occidentalists would never be able to purge the Traditionalists from Kehkal as they would end up doing in the government and in other provinces with the help of the internal dissensions between the various Oniyists movements. In fact, as the Occidentalists themselves would lose power to other factions at the Court, Oracles and sorcerers would only gain more power thorough the Province.

Government and politics

Kehkal is ruled by the Keh Yajaw, nominated by the K’uhul Ajaw and confirmed in his functions by the Tz'onch'ob. Executive and judicial powers over the Yajawil reside in him, but it’s the Ch’ob that is competent over matters like the development and growth of the province and divide the allocated budget.

As they went through the Eastern Winds, the Sunrise, and the Cohabitation, the Kehache created around themselves a strong rural and religious identity. Since the end of the First Green Revolution, conservatism has been the main project of the rural and perirural populations as they try to protect what they have acquired during the sixties, and preserve their lifestyle. Oracles and Temples remain especially strong in the north of the Province, where nostalgia for the hayday of the Green Revolution remain high.

Because of its most diverse background, greater connectivity with the rest of the country, and lesser reliance on agricultural products for their livelihood, the populations in southern Kehkal remain torn between the protection of the model acquired from the Green Revolution and the wish to improve the Province's economic and social situation by modernizing the system to be more in phase with the current society of the Mutul. Politicians from these Kuchkabals thus tend to favour positions and policies crloser to Rezeism and Meridionalism and are often accused by the province's conservators of being "Modern Orientalists".

Economy

Agriculture

Kehkal' environment is typical for the Xuman Peninsula: it is dominated by a geological karstic topography of limestone, coral and dolomite with little or shallow layers of topsoil. In this situation not a lot of agricultural modifications are possible and Kehkal remain dominated by one system of production: the Xukalpuh.

The Xukalpuh is a crop-growing system used throughout the Mutul. the Xukalpuh cycle is made of four stages: an intensive exploitation of the three sisters, followed by a transition stage were Quick-yielding fruit trees, like plantain, banana, and papaya are planted and cultivated within a year. Fruit trees that need more time to produce are planted amidst the maize, beans, and squash to bear fruit in five years. Their maturation, and the resulting canopy, mark the beginning of the third stage where fruits are harvested for a few years while hardwoods, such as cedar and mahogany, are planted to mature over the next decades. Finally, in the final stage of the cycle, the forest is left to regenerate. The hardwoods rise above the fruit trees to create a high canopy. Farmers generally leave deers and turkeys to roam in the forest to add more values to their production. When the time is considered right, remaining animals are hunted for their food and hides while the precious essences of wood are collected. Remaining trees are cleared and burned to enrich the soils and the cycle can start anew.

The core of this system has remained mostly unchanged since prehistorical times, although the Green Revolution has introduced new practices, improved crops, mechanisation (whenever possible), fertilizers and so on, the Xukalpuh' popularity as an agricultural system and its success can be resumed in a few points:

- Genetic diversity: the Xukalpuh is a form of Polyculture. High diversity within a field (a documented 95 varieties from 28 different species in use in Xukalpuh) minimize the risk of crop failure due to diseases or bad weather, two ever present threats in a tropical region.

- Dispersed settlement-pattern: Kehkal' population is mostly dispersed in a network of low-density hamlets with very few settlement that can be referred to as "urban". This dispertion maximize the cultivated land area and thus minimize the risks of all farmlands being affected by the same climatic conditions.

- Availability of land: one of the factors favourable to high production is that all land in Kehkal are dedicated to the XUkalpuh. Very few other production systems are promoted and only in very specific conditions.

- Communal land: Farmers rarely -if ever- own the lands they exploit beyond their residence's garden. Farmlands belong to the Nalil, or "District", who then grant usufruct rights to individuals, who then farm their plot and collectively maintain communal holdings. It is the role of the District-leader, the Aj K'uch K'ab, to handle the rotation of crops and lands. Once again, the purpose of this collective ownership of the land is to maximize the cultivated area so to minimize the risk of catastrophic failures' involving all of the farmlands. This role of the District-leader in the management of the system lead directly to the final reason for the Xukalpuh' high yields:

- Involvement of the Elites: because of their involvement, the ruling class has yet to try hard to eradicate or substitute the Xukalpuhob with other production systems less adapted to the Province' environement. Instead, Xukalpuh reliable production year-to-year is used by the Divine Throne to build up its strategic food reserves to distribute across the Mutul in case of shortages.

3.534 million of the 4.363 million hectares in Kehkal are exploited following the Xukalpuh system, with farmlands at different stages of exploitation. The main productions are thus maize, beans, and squash of different species and varieties. Other products include melons, tomatoes, chilis, sweet potato, jícama, mucuna, plantains, banana, papaya, avocado, mango, citrus, allspice, guava, cherimoya, breanuts, hardwoods, venison, poultry, and honey among others.

Culture

Religion

Cuisine

The Kehach cuisine is famous for three elements: venison, chocolate, and snails and Kehach dishes do not betray this reputation. As part of a broader campaign to revitalize the tourist industry, Kehach Snails have been proclaimed to be the "Provincial Dish" of the Yajawil in 2013. They are prepared by boiling the snails, extracting them from their shells, washing and filling the shell with chocolate-spice paste, put back the snails into their shell and covering them with the same paste, and then roasted before serving. They are considered to be part of the Province's Haute cuisine which is promoted by the Yajawil authority as a way to break the "backwater" image associated to Kehkal.

Because of a strong hunting tradition, poultry game and venison are common source of meat in Kehkal. Meat is much more present in Kehach cuisine than it might be in other part of the country, especially before the 20th century when the Kehache were famed for their hunting skills and strong stature given by their meat-rich diet which, incidentally, solidified their image as the "Savages of the Xuman". The most popular and famous of their venison recipe is the B'oxk'eh (if prepared with deer meat) or B'oxch'iich (if prepared with dark-meat poultry). Ingredients include a marinade made with either Pineapples and Papaya or Lemon juice and sour orange, and a sauce prepared with chili powder, cinnamon, and chocolate.

But despite these strong characteristics, Kehache cuisine nonetheless share a number of elements with other Xuman traditions. These include dishes like turkey stews, lime soup, and peculiar methods of cooking known as Pibil and Pok Chuk.