Chaan Dynasty

Chaan Chaan Nimja | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 BC - 250 AD | |||||||||

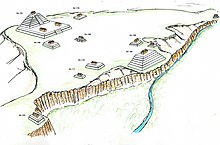

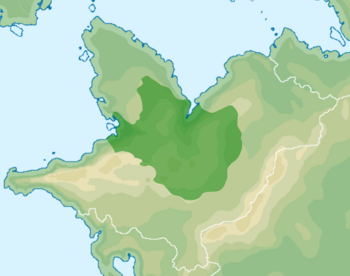

A map of the Chaan Mutul at its greatest extend | |||||||||

| Capital | Yux | ||||||||

| Common languages | Classical Mutulese | ||||||||

| Religion | White Path | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| K'uhul Ajaw | |||||||||

| Historical era | classical | ||||||||

• Personal Union of Yux and Izapak | 300 BC | ||||||||

| 315 BC–300 BC | |||||||||

| 266 BC-265 BC | |||||||||

| 250 BC-233 BC | |||||||||

| 250 AD | |||||||||

| |||||||||

The Chaan dynasty (Mutli : Chan Nimja) was the second divine dynasty of the Mutul, preceded by the 50 years long Nakabe Revolt, and then followed by the War of the Princes. It lasted for over 470 years, from 320 BC to 250 AD, and is considered a golden age of the Mutulese history.

The period saw a number of limited institutional innovations. The Chaan government centralized the prerogatives traditionally reserved to rulers, such as the control of the roads and of waterways, with strengthened control over marketplaces, banks, and various lenders, while the aristocracy continued to be responsible of the transport of goods and products from markets to markets, from the producer to the consumer. Science and technology during the Chaan period saw significant advances including the process of papermaking and the use of negative numbers in mathematics.

Etymology

The Dynasty was not named after its founding clan's name, but instead from it's glyph-emblem, representing a snake. The Ahk Family, so called because many of its members had the "Ahk" in their glyphic name, chose the snake, Chan or Kaan depending on the dialect, to honor the Vision Serpent, the gateway to the divine realm and a reminder of the family's origins in Divination.

History

Traditional Myth

According to traditions and the records kept by the Chaan, the Ahk lineage began when one of K'o's, the First K'uhul Ajaw, daughters gave birth to a son, Siyaj Ahk, fathered by a minor divinity of the underworld. After proving the veracity of her words to her father, by quoting in the Underworld's language her lover's titles, she was given the direction of a Temple covering a door to the Underworld. She gave birth during the travel, and the child was carried in a turtle shell. During his childhood, the half-god, great-grandson of Chak and son of a god of the Underworld, proved to be a great Oracle, capable of communicating with both the upper and under worlds. He became famous for his wisedom and prophecies, and was even invited to his uncle's, the new K'uhul Ajaw, court despite his unclear paternity and the possible threat he could become to the Divine Lord's authority. He nonetheless served as the main priest and oracle of the court, given the charge of Kaminyajunlyu main temple and the direction of the associated school for the elite. He notably became the personal teacher of the B'ah Ch'ok Ajaw and then his main advisor.

It was through Siyaj Ahk's origins that the Ahk Lineage explained their gift in divination and long held positions as oracles and seers. They would remain important nobles at the Paol'lunyu court for all of the Dynasty's duration. During the second half of the Dynasty, the Extensive Period, an Ahk and close friend of the Ka Lineage received lands from the latter in the recently conquered north, with the task of establishing a city capable of both protecting the western border of the Mutul against aggressors and serving as a trade hub with the Chik'inli. The legend says that it's in a ritually-induced vision that the perfect location for that city was revealed to the Ahk, who then founded the city of Yux. Yux would remain a major vassal to the Ka and their city of Nakabe, protecting their western flank against ennemies and serving as a major source of both funds and men for their wars.

But ultimately, Yux loyalty's to Nakabe was weakened by the latter's growing centralization, always increasing demand, incessant warfare, and complete abandon of its vassal against the Yakalmek Kingdom, a nominal allies of the Ka who nonetheless continued to raid and harass Yux. This led to Iztam K'an Ahk's rebellion in 340 BC, supported by Izapak, the rival of Nakabe.

Yux-Izapak Co-Dominion

Itzam K'an Ahk's son, Wabak'el Chaan married Lady Ek Janab, solidifying Yux's alliance with Izapak. When the K'uhul Ajaw of Izapak died without an heir, it's Lady Ek Janab who secured the throne for herself. Thus both Mutal ended up in a co-dominion, ruled by two K'uhul Ajaw married to one another, once Wabak'el Chaan rose to the throne of Yux too.

This joint rule would last from 327 to 300 BC and would see the defeat of the Ka Dynasty and the de-facto re-unification of the Mutul in 315 BC with the reconquest of Oxmal. However, it's not until the death of both monarchs that their son, Yax Chaan Ahk would unify both crown and claim the Divine Lordship of all of the kingdom, officialy starting the Chaan Dynasty.

Yax Chaan Ahk

At the beginning, Yax Chaan Ahk divided the Mutul into eighteen Ajawils. While he himself continued to rule Yux in person, he granted titles and positions to many of his family members. For example, Izapak was divided between two of his brothers, Oxwitik and the Eastern March was granted to a third one, Takalik was given to a cousin and so was Olpamal a new Ajawil matching more or less the borders of the old Kaminyajunlyu. Other Ajawils were granted either to generals and administrators that had proved their worth under his parents' joint rule, and some local dynasties of rulers were re-installed in their thrones in exchange for their allegiance to the Chaan.

Beyond these administrative reforms, Yax Chaan Ahk was mostly concerned with securing his kingdom's borders. In 296 BC, he conquered the Yakalmek kingdom, an old rival of Yux when it was still a vassal of Nakabe, and overthrew its royal family, turning the kingdom into a Kuchkabal and integrating it directly to his Ajawil. In 293 BC, he waged war against Lakam Tun, Man T'e, and Akol. Three northern neighbors and ex-vassals of Nakabe and thus ennemies of the Chaan. With these wars, Yax Chaan Ahk had pacified the northern border and was free to return to his capital, his rule secured. His prestige would also allow him to intervene in multiple conflicts between Tzib’ahal city-states to his west, securing precious allies and trade roads, placing them de-facto under his protection.

But the largest war Yax Chaan Ahk would lead would be against the Ytze Kingdom from the Xuman Peninsula. This northern state tried to place Akol, Lakam Tun and Man T'e under its hegemony. All three states called the Chaan for help, and Yax Chaan Ahk answered positively. This first Chaan-Ytze war would last from 280 to 277 BC, saw the final destruction of Akol, and the integration of Man Te' and Lakam Tun into the Mutul. A second Chaan-Ytze war began in 274 BC, but came to an abrupt stop with the death of the K'uhul Ajaw in 271 BC.

Three Princes Rebellion

The second K'uhul Ajaw, Ka Chaan Ahk, was unable to continue his father's war, as he was more concerned with his inimical relations with his cousins. In 268 BC, the young Ajaw of Takalik died alongside his lineage, distant relatives of the K'uhul Ajaw that had been placed in charge of the city 52 years (a "Mutulese century") ago during the Yux-Izapak co-dominion. Ka Chaan Ahk took the opportunity to claim back Takalik, despite the contestation of one of his cousins, Ikch'e Muwal, Ajaw of Izapak, who claimed that since he was more closely related to the late Takalik Ajaw he should be the Ajawil's inheritor. In 267 BC, the governor sent by the Divine Throne was ambushed while passing through the Central Valley, but managed to escape. The next year, he returned at the head of a small military contingent and the small Izapak garrison that had occupied Takalik was forced to leave the city. In response, Ikch'e Muwal organized a rebellion. Active participants included the Ajawils of Izapak, Ch'e, and Olpamal, all related to the K'uhul Ajaw, but also Malpimel and Jumpat, two Ajawils led by rulers not related to the Chaan Dynasty but nonetheless on friendly relations with the rebel Ajaws and opposed to the any threat to their de-facto independence. The Ajaw of Yajanite was forced by Ikch'e Muwal to offer supplies and weapons to the revolt after a Izapak army, made mostly of Ben 'Zaa mercenaries, besieged his capital. In the north, the Ajaw of Apikal also considered joining or supporting the rebellion, but ultimately decided to remain neutral. Of the lineages related to the Chaans, only the ruler of Oxwitik refused to join the rebellion. The last of the "southern principalities",Ujuxte, despite being surrounded by rebels, also refused to join.

The rebels fortified the passes of the Central Valley and sent troops to siege down Takalik. Small contingents were sent in punitive expeditions against Ujuxte and Oxwitik. The rebels counted mainly on Ben 'Zaa and Tzib’ahal mercenaries to defend the northern border of Izapak, while their main force were busy around Takalik and the Central Valley, where they were expecting the blunt of the Chaan response. However, Ka Chaan Ahk sent his elite forces directly on Izapak, reinforced by the Ch'ichwitz army, and defeated the Rebels there, capturing Izapak in less than a month. Ka Chaan Ahk was then joined by the Ajaw of Yajanite, and their bostered forces marched on Ch'e, the real core of the rebellion. The Principality fell three months later. All in all, the Rebellion lasted only 9 months before the remaining principalities surrendered, and the K'uhul Ajaw himself entered Takalik.

Following the Rebellion, the power of the Blood Princes were greatly reduced in favor of local dynasties of rulers. New Ajawils were carved out of the Rebels' lands to reward those who had been loyal to the Divine Lord. The Ajaw of Ujuxte for example, received the entirety of Malpimel and was titled "Administrator of the Southern Expansion", greatly reinforcing its prestige and wealth.

Eastern Expansion

Almost since its creation, the city of Oxwitik had been at war with the Lencas to its east. It notably faced many coalitions, the most proeminent of which were led by the cities of Yarumela, Ullu, or Yajo. During the Expansive Period of the Paol'lunyu Dynasty, Oxwitik had managed to conquer most of the Lenca Bassin, turning its most proeminent city, Yarumela, into its vassal. But when the Nakabe Revolt began, it quickly lost its hegemony over the region and Yarumela was reconquered. Ultimately, Oxwitik fell and was only recovered by the Mutul in 315 BC. After that, the Chaan Dynasty was unconcerned with the Eastern Border.

When he became K'uhul Ajaw, Yax Chaan Ahk offered the city to the eldest -after him- of his brothers. This lineage of their House became known as the Ox Chaan. 30 years later, the same brother would refuse to join the rebellion against his nephew of the main line and even fought back against Rebels "Punitive expeditions". As a reward for their loyalty, the Ox Chaan were granted control over more lands, and were exempted from paying tribute to Yux for 9 years.

Using this opportunity, the Ox Ajaw allied with a number of other Ajawils and with the distant agreement of the K'uhul Ajaw, launched a serie of campaigns against the Lencas. He took Yajo in 262 BC, and defeated the next year a confederation of Lencas led by Yarumela. While he made tributaries of the Lencas towns and cities that surrendered to him, the Ox Ajaw also established colonies, as was done on the southern border., to further secure his control of the region and improve production of the luxury goods he could export to the rest of the Mutul. However, these nine years of expansion were only the beginning of a century of warfare, slow expansion, and colonisation.

Tzib’ahal Wars

The Tzib'ahal city-states had been placed under the protection of the Chaan Dynasty by Yax Chaan Ahk. But because of the Three Princes Rebellion, they were able to regain their political autonomy. The city of Ixmul became the figurehead of a league of minor cities opposed to the control of the Chaan-friendly Honochtun. The League took and plundered it in 265 BC, to the surprise of their contemporary. Following this success, the League further united by forming the Kingdom of Maktun, with the lord of Ixmul, Itzam Kan Ek, being proclaimed as their ruler. In 264, Itzam Kan Ek re-occupied Honochtun, turning it into its new capital.

Placed in front of the fait-accompli, Ka Chaan Ahk did not oppose to the rise of this new kingdom. In 260 BC, Itzam Kan Ek died and his son, Balam Kan Ek, took the portuary city of Chelnal from the Island-kingdom of Ox Amul T'e. This was the beginning of a five years long war from which Maktun emerged victorious, turning Ox Amul T'e into a tributary.

The growth of the Maktun Ajawil was favored by the Ytza Kingdom, which wished for a poweful ally to help them fight against the Chaan Dynasty. In 254 BC, ambassadors from cities in Southern Tzib'ajal, threatened by the rise of the Maktun Kingdom, were present at the coronation of the K'uhul Ajaw Yuknom Ch'en, possibly to urge him to help them against their menacing northen neighbor. If so, the new Divine Lord heeded their words, as he sent an ambassy to Balam Kan Ek in 251 BC, announcing that the major city of Joy Chan was considered by the Mutuleses as an ally and would be protected in case of an invasion. This does not seem to have deterred to the Muktun monarch, as he laid siege to the city in 250 BC. Yukn'om Ch'en then led three campaigns against the Muknal kingdom : in the first one, he went to Joy Chan's assistance. In the second one, the next year, he defeated Balam Kan Ek on the battlefield and plundered Ixmul. Finally, the third campaign was a pre-emptive war against Balam Kan Ek launched in 247 BC, capturing the Tz'ibahal king, and then sacrificing him back in Yux. This was not the last of Yuxnom's campaigns however, as he then waged war against Ox Amul T'e between 245 and 242 BC, as the latter had attempted to retake the cities they had lost to the Muktun Kingdom, something the K'uhul Ajaw opposed. Fearing what this decision meant, the encroachement of the Mutul in Tzib'ajal and the loss of their autonomy, Joy Chan and other southern cities betrayed the Mutul, joining Ox Amul T'e in their war. In this they were joined by many of the late Muktun kingdom's cities, who couldn't bear the Mutulese hegemony. In 240 BC, all of these insurgencies officialy united and formed the League of B'ahakal. It would take seven more years for Yuknom Ch'en to defeat the League, taking over all of Tzib'ajal.

The treatement of the region after the wars was surprising: Yuknom Ch'en decided to run contrary to the tradition, which was to divide conquered territories among family members and generals. Instead, The K'uhul Ajaw retained all rights over the conquered lands, and administered them as part of his own territories. In that, Yuknom Ch'en was truly a successor of his father, who had seeked to reinforce the K'uhul Ajaw position inside the Divine Kingdom. And so, despite having given up all of the recently reconquered southern regions and divided them between his brothers, Yuxnoom was able to strenghten and consolidate the K'uhul Ajaw' powers, paving the way toward a more central and bureaucratic Mutul and slowly abandoning the feudal practices of the Paol'lunyu Dynasty.

One Lord Two Princes

The rule of Ix K'ultun, daughter of Yuknom Ch'en and his successor, is often referred to in poetic chronicles as the era of Hun Ajaw Ka Ch'ahom, officialy translated as the era of "One Lord and Two Princes". The name come from the three dominant figures of this quarter of a century: Ix K'ultun herself, the Ajaw of Apikal: Chan Ta Batz', and the Ajaw of Oxwitik: B'ah K'awak.

Ix K'ultun continued her father's policies after his death in 225 BC, reinforcing the royal administration and structures of the monarchy. In 222 BC, she sent "Inspectors" to control the market prices and handling of justice in her cousins territories. This was only the beginning of a long serie of political actions aimed at re-establishing royal control over the southern territories of the Mutul. By 220 BC, all her cousins had been deposed and their Ajawils were reformed into two new "Yajawil", non-inheritable titles granted by the Divine Queen to replace the dynastic Ajawils. Futhermore, the title of "Administrator of the Southern Expansion" was taken away from the rulers of Malpimel and granted to a new Inspector. Similarily, in 219 BC, the rulers of the Ajawils of Ch'ichwitz and Xultun exchanged their principalities by the order of Ix K'ultun, de facto turning them into Yajawils. However, neither of their clans opposed the decision as these two families held their power and wealth from their military and civil services to the Throne.

This growth was vehemently opposed by the eastern Ajawtak. Chief among them was B'ah K'awak, Ajaw of Oxwitik and relative of Ix K'ultun, and Chan Ta Batz', also known as the "White Lord", of Apikal. Both defended the privileges of the Ajaws and of their lineages against the centripetal forces in Yux. Their opposition was mostly done through diplomacy and court intrigues but when B'ah K'awak began to be called "B'ah Ajaw" by the other princes in his orbit, Ix K'ultun supported the revolt of the Lencas against Oxwitik in an attempt to diminish her cousin's powers.

This almost open conflict led to Chan Ta Batz' sending diplomatic missions to the Ytze Kingdom with the express purpose of negociating a secret alliance against the Chaan. The crisis was averted when, discovered, Chan Ta Batz immediately dropped all ties with the Ytze. This angered the four Kan Ek Ajawtek, the leaders of the Ytze, greatly and in response sent raiding parties into the Mutul. It would be the start of the 18 Pax 2 Ajaw Ytze-Mutulese War, a serie of military campaigns and back-and-forth that would last from 215 to 202 BC.

Ix K'ultun and Chan Ta Batz had been de-facto allies against the Ytze. During and after the war, both established, or rebuilt, forts and garrisons across the northern borders to prevent further assaults from the Ytze and help spring their own military campaigns into the northern kingdom if necessary. However, after the war came the question of maintaining and financing these garrisons. Ix K'ultun tried to put all of them under her direct command while also demanding that Chan Ta Batz pay a greater tribute to support them, still not trusting him. the White Lord, meanwhile, wanted to pay for and command the garrisons he himself established, leaving the others to Ix K'ultun.

Ix K'ultun died in 199 BC but her son, Il Chan, continued to demand that Chan Ta Batz hand over his northern garrisons. But, taking advantage of the transfer of power, the White Lord had claimed more garrisons and troops, seizing their forts, and refused the new K'uhul Ajaw' demands.

In preparation for a war, both the Divine and White Lords courted the aging B'ah K'awak, who had resumed his control over the Lencas states, for support. But before he could chose whom to support, having deliberately stalled diplomacy so to better control negociations, events happening in the north would turn out to have dramatic consequences.

Puy had been a vassal city of Apikal. It's rulers were appointed directly by the Lords the latter city. During the 18 Pax-2 Ajaw War, Chan Ta Batz' established T'e K’inich II as ruler of Puy, maintaining the local ruling dynasty in power. T'e K'inich II proved his bravery and military strength during the war, serving as an officer in Apikal' army. But after the war, relationship between the lord and his vassal soured when T'e K'inich II began protesting Chan Ta Batz' taxe raised and aggressive policies toward the K'uhul Ajaw in Yux. As a response, in 200 BC, Chan Ta Batz' send punitive expeditions to raid Puy', devastate its countryside, and capture T'e K'inich II. However the latter managed to flee and take refuge among K'ol clans allied to his family.

Chan Ta Batz' arbitrary punishment shocked his vassals and potential allies, but allowed him to continue his military and financial reforms unopposed. In 197 BC, he had de-facto acquired B'ah K'awk support, who himself had gathered a strong military and was secretly almost ready to proclaim himself Divine Lord, and had a standing military far larger than that of the Chaan Dynasty. Il Chan sent orders for all private militaries in the north of the Mutul to disband, but the White Lord ignored these orders and continued his aggressive preparations. In reaction, Il Chan declared his vassal a rebel and sent a punitive expedition toward Apikal.

Il Chan was defeated at the battle of the Snake Pass in 196 BC, after which he retreated to the northern garrisons that were still loyal to him. Instead of marching directly toward Yux, which would've left his flanks at the mercy of potential raids and attacks from the Chaan troops, Chan Ta Batz' began to lay siege to the Northern Garrisons, to take them one by one as a way to definitively secure his future march on the capital. During these operations, the White Lord managed to gain the support of the Ỳtze Kingdom which wished to see these threatening fortifications on its border destroyed as promised by their new ally.

Surprise came when T'e K’inich II re-appeared at the head of a large army made of K'ol clanmen who joined his cause, but also of Chaan loyalists and veterans, survivors of the Snake Pass or of the first garrisons to have fallen to the White Lord who couldn't rejoin with the K'uhul Ajaw. In the previous years, T'e K'inich II and Il Chan had managed to contact one another and make an alliance. T'e K'inich retook his fief of Puy without a fight in 195 BC and then the following year, proclaimed a Star War against Apikal. He took over and devastated the city. Chan Ta Batz' was forced to retreat and march back to his fief to try and stop his ancient vassal, but he fell into a trap and was captured, ending his rebellion.

Society and Culture

The Chaan became a prime example of the Mutulese Trifunctional hypothesis, which postulate that at least until the Ilok'tab Dynasty, if not after, the Mutul was divided into three classes or castes : the priests-scribes, the trader-nobility, and the artisans-commoners. The K'uhul Ajaw was at the apex of that society. Ranked immediately below were the Yajawob, generally translated as "vassal lords", "Princes", or "Dukes" depending on the authors. Yajawob could be from the same dynasty as the K'uhul Ajaw or from local lineages, a common case in remote regions where the central powers had difficulties imposing itself. The rest of society was composed of nobles lower than the Yajawob and all commoners, plus the slaves.

Market Network System

The Chaan relied on a strong middle class of skilled and semi-skilled workers, artisans, and landowners. Governing these "Commoner-producers" was a smaller class of specially educated merchant governors who would direct regional economies based upon simple supply and demand analysis. This aristocracy would thus ensure both the circulation of trade goods and its protection, legitimizing their rule. At the top of the structure was the K'uhul Ajaw and an his array of advisers who would manage trade between Yajawils but also with other kingdoms, ensure that regions remained stable, inject capital into specific sectors and authorize construction of large public works (even if that last prerogative was devolved to regional governors). Advisors and government agents came from a specialist class, called nowadays the "Priests-scribes", which included clerics but also professions like artists, mathematicians, architects, advisers, and astronomers who would sell their services and create luxury goods based upon their specific skill set.

Market economy was predominant during the Chaan Dynasty. Cities were highly integrated and urbanized. Small towns did not need to take part in long-distance trading and limited trade to local exchange. This created a multitiered structure, where locally produced goods would be exchanged at local markets, to be exported to regional ones, and then be spread all thorough the kingdom depending on the analysis of the demand made by the merchant-aristocracy. The most important markets were also the political centers of the Chaan Dynasty as the seats of the Yajawob. There is a strong parallel between economic and political structures, as Yajawils corresponded roughly to a "Regional Market" and all the associated smaller "local markets". This structure was given the name of the "Market Network System", highlighting the dual nature of the Mutulese aristocracy, both political and financial.

Justice

Under the Yajaw was the Halak Winik and then the Batab. The Batabs were administrators of smaller towns or of urban districts in the larger cities. They were responsible for carrying out the laws issued by the K'uhul Ajaw or the decrees of the Yajaw and Halak Winik above them. They also served as judges for their towns and adjudicated civil and criminal cases. Court cases were generally handled swiftly in public meeting houses known as popilna, generally located near or at the market. Witnesses were required to testify under oath and the parties were represented by individuals who functioned as attorneys. Decisions made by the Batabs could be appealed and the case would then go the Halak Winik, but it seems to have been an uncommon procedure. The victims could pardon the accused, thus reducing their punishment. Sentences were carried out immediately by the tupiles as the Chaan did not maintain prisons and preferred corporal punishments on public spaces, up to and including the capital punishment.

If a crime occurred that affected an individual in another town, the batabs in the two towns would work together to ensure that issue was resolved. The Batabs generally acted independently, but would consult with the Halak Winik on serious cases. Halak Winiks and Yajaws could decide to personally handle a case, but this was a procedure generally reserved for cases involving the nobility.

The Chaan criminal laws were severe. Murder, rape, incest, treachery, arson, and acts that offended the gods were punishable by death. However, it distinguished between intentional and accidental acts. For example, individuals who were found guilty of homicide were sentenced to death. If an individual was found guilty of manslaughter however, he was sentenced to repay the family of the victim by giving up one, or more, of his slaves. If the criminal was a minor, he could be sentenced to slavery. Nobles who were found guilty of crimes were forced to have their faces permanently tattooed as a symbol of their crimes.

Adultery was considered a criminal offense. Married women who committed adultery were publicly shamed and their lovers were stoned to death. Their husbands had the option of leaving the marriage and finding a new spouse. Married men who committed adultery were sentenced to death unless their extra-marital affair was with an unmarried woman.

Pardons were available for criminals. Adulterers could avoid punishment by being pardoned by the injured husband, and families of murder victims could demand restitution in lieu of capital punishment.

Food

Chaan cuisine was varied and extensive. Much of the food supply was grown in agricultural fields and forest gardens, known as pet kot. Their diet focused on four domesticated crops maize, squash, beans and chili peppers. Maize was the central component of the diet and had a profound influence on the Mutulese culture. It was used and eaten in a variety of ways, but was always nixtamalized.

Along with maize, beans—both domestic and wild—and squash were relied on. With time, manioc cassava was added to the roaster of staple crops of the Divine Kingdom, almost equaling maize in importance. Cacao was especially prized by the elite, who consumed chocolate beverages.

Sunflower and cotton seeds were grounded to produce cooking oils.

Dogs, terror birds, turkeys, and ducks were raised for their meat while deers were mainly obtained through hunting. Maritime resources, including fish, lobster, shrimp, conch, and other shellfish, would also be used to supplement the diet, especially in coastal area but also deeper inland, as fishes were delivered to aristocratic houses far from any coast alive, as supported by archeological evidences.

Government and politics

Under the Chaan, the position of the K'uhul Ajaw took its modern prerogatives, being the supreme judge and lawgiver, the commander-in-chief of the armed forces and sole designator of official nominees appointed to the top posts in central and local administrations. Theoretically, there were no limits to his power.

Below the K'uhul Ajaw was his cabinet of close advisors and ministers, known as the Bacabs or Bolon Tz'akabs depending on the time period and their numbers. An exception was the position of supreme military commander, the Chak Nakom, which wasn't counted among the ministers despite his responsibility as he only served for a three years term. Many other adivsors and courtisans frequented the K'uhul Ajaw's court, the K'uhul Holpop, which ultimately was the organ that limited the Divine King's powers.

Local government

The political units of the Chaan Dynasty were, in descending order of size, the Yajawil, the Kuchkabal, and the Batabil. A Batabil was then divided into multiple wards, known as Nalil. Each Nalil was led by an Aj Kuch Kab.

The head of a Yajawil was a merchant-governor known as the Yajaw acted as semi-independent rulers of their own petty kingdoms. They were nonetheless under the tutelage of the K'uhul Ajaw in a far greater extend to that of the previous dynasty, as it was the Divine Lord who chose who could inherit a Yajawil, even if customs mandated that the candidate had to be from the same lineage as his predecessor. Each province also had a high-priest who led a hierarchy of priests, determined the dates for festivals and ceremonies, and foretold auspicious events.

The Yajaws appointed the Halak Winiks, the rulers of the Kuchkabals under them. The Halak Winik’s power was limited by his council, the Holpop, made of the nobles of elite lineages from his Kuchkabal.

Economy

Agroforestry

Forests supplied essential ressources for the Chaan, such as fuel, construction material, habitat for game, wild plant foods,and a pharmacopoeia from medicinal species. By far the heaviest demand on the forest was firewood needed for cooking. The firing of ceramics also required substantial amounts of fuel. The production of lime, essential for plaster, also required considerable fuel input and it was estimated to require 5kg of wood to produce a kilogram of lime. Wood required forconstruction timbers and artifact manufacture created an es-sential, but less voluminous demand.

During the Chaan Dynasty, the Mutuleses could've compensated shortages in forest productivity through the importation of pine wood from the the West or tropical wood from the jungles in the south, east, and sometime even from the north, as well as temporarily using intensive forestry techniques to a fixed-plot agroforestry system.

Most of the Chaan wood production came from Managed forests and managed fallows. Most commonly found on slopes and ridges, these forests controlled erosion and protected the watershed. They could also be found alongside streams where they created shady Riparian zones. Different parts of the forests were managed for different groups of ressources: a small stand for trees useful for construction, a parcel of avocado trees, a stand of copal trees, a chocolate grove, a patch for firewood trees... the composition and size of each reflected the objectives of the individual farmer or of the landowner.

In the Xuman Peninsula, where rivers and surface waters were rare, the Chaan and other Mutulese peoples not necessarily under the Chaan's hegemony built patches of man-made jungles known as Pet Kot (Utaan: "circular stone wall") so called because of the characteristic low walls that surrounded them. These enriched patches of tall forests contrasted, and stil do, with the surrounding low deciduous trees that dominate the region. Introduced species sometime came from local forests, homegardens, or even from distant humid jungles to the south of the Mutul. Pet Kot near areas of shifting cultivations also provided farmers with a shady, ressource-rich place for rest when out in the fields.

Other types of enriched forest orchards were also created around cenotes, scattered patches of deep soils in karst areas. These tended to be far smaller, often called "micropatches" of forests, but they were also a significant source of fruits and wood in areas that were otherwise droughty.

Agriculture

Crops used at the time of the Chaan in agricultural fields included Maize, three species of beans, two of squashes, and several species of root crops, including sweet potato, achira, and macal. There are evidences that the culture of Manioc, imported from Sante Rezeand the Ucayare forest, already reached the Mutul at the time. Orchards of Acrocomia aculeata, sapote, jocote, nance, and avocado were also maintained. These Orchards were planted adjacent to household compounds, sometime even directly inside cities where they belonged to a specific neighborhood.

cacao was cultivated not only in its original humid forests, but also in regions were it couldn't grow naturally, in artificial sinkholes where they wereprotected from the heat and could be watered during the day. The culture of cacao was helped by leguminous trees symbionts providing cover for the shade-loving cacao, and also helping fix nitrogen in the soils and fertilizing it.

Intensively managed fields of maize, other seed crops, and root crops were found all around the main settlements and villages. Studies show that the Chaan required 0.18 hectares to support an individual using the techniques of their time. As a result, especially around large urban areas, a short fallow system was used, with ratios of planting to fallow years of either 1:3 or 3:5. In areas less populated and with more lands, more sustainable long fallow systems that were used instead. To facilitate production in a short fallow system, Chaan farmers practiced multicropping with leguminous annual crops to help prevent yield decline.

Phosphorus was a critical element often in short supplies in densely cultivated areas, especially in the North of the Chaan Mutul. soils may have been naturally renewed via the capture of windblown soot, dust, and volcanic ash from central and western Mutul.

Uplands were not the only areas cultivated. both permanent and seasonal wetlands were active areas of intensive culture, especially their margins. Chert-lined terraces, created to prepare planting beds and prevent soil erosion, were ubiquituous. It is estimated that as much as 40% of the wetlands were exploited for agriculture during the Chaan Dynasty.

Pottery

The central highlands of the Mutul has a rich geological history comprised mainly from a volcanic past. The metamorphic and igneous rock, as well as the sand and ash from the pumice areas provide many types of tempering. In the area, there are a range of clays that create varied colors and strengths when fired. During the Paol'lunyu and Chaan Dynasties, the Mutuleses located their clays in the exposed river systems of the highland valleys. Once the clay and temper were collected, pottery creation began. The maker would take the clay and mix it with the temper (the rock pieces, ash, or sand). Temper served as a strengthening device for the pottery. Once worked into a proper consistency, the shape of the piece was created.

The Chaan did not invent the Potter's wheel. Instead, they used coil and slab techniques. Once the pot was formed into the shape, then it would have been set to dry until it was leather hard. Then, the pot was painted, inscribed, or slipped. The last step was the firing of the vessel. Kilns were used to fire the vessels, and they were normally found outside in the open air. they were fired by wood, charcoal, or even grass.

Polychrome pottery was a luxury item not commonly available to the general population. Figural Polychromes were an elite prerogative, probably produced by and for other elites. The lidded basal flange bowl was a new style of potter to add to the already growing repertoire. This type vessel usually had a knob on top in the form of an animal or human head, while the painted body of the animal or human spreads across the pot. Many of these pots also had mammiform supports, or legs. These unique vessels served ritual functions, during sacrifices, offerings to the spirits, and dedication rituals. They are also found among burial goods.

Textile

One of the two most common occupation for Chaan women was weaving clothes for their family. Some villages became so famous for their cloths that women there formed large cooperatives aimed solely at exporting their production to the rest of the Divine Kingdom. They had two natural types of cotton to work with, one white and the other light brown, called Kuyukat'e, both of which were commonly dyed. The preparation of cotton for spinning was very burdensome, as it had to be washed and picked clean of seeds. The cotton was usually associated with the elites.

Elite women were also given the opportunity to work with the most expensive feathers and pearl beads. However, women of the elite not only had to prepare the best clothing for their families, but they also had to be talented in weaving tapestry, brocade, embroidery, and tie-dyeing for tribute to other families and rulers.

Beside cotton, weavers also worked with maguey. It was of major value as a cordage material, but was also used to create nets, hammocks and bags. Other fibers more rarely used included human and animal hairs, and Chich'ikatze.

There were two kinds of looms used for weaving, the foot loom and the back-strap loom. The latter is still in use in some regions of the Mutul today, where women attach one end of the loom to a tree or post and fix the other end behind their lower back.