Naikangese Civil War: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 95: | Line 95: | ||

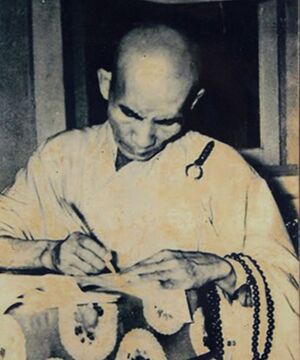

[[File:Xu-Ti-Na.jpg|thumb|left|[[Xu Ti Na]], a [[Naikanghi people|Naikanghi]] {{wp|Buddhism|Buddhist}} monk and one of very few Naikanghi permitted to attend the [[Tatchossey Conference]].]] | [[File:Xu-Ti-Na.jpg|thumb|left|[[Xu Ti Na]], a [[Naikanghi people|Naikanghi]] {{wp|Buddhism|Buddhist}} monk and one of very few Naikanghi permitted to attend the [[Tatchossey Conference]].]] | ||

The fairness of the Tatchossey Conference has been hotly debated in the conference's aftermath. Most of the conference's attendees highlighted that it | The fairness of the Tatchossey Conference has been hotly debated in the conference's aftermath. Most of the conference's attendees highlighted that it brought unity to groups which had previously been disparate, and even today, many Chengshengese and Myacha people hold it up as a triumph of ethnic cooperation over mistrust. Among Naikanghi, however, the reaction was almost universally negative. Xu Ti Na's response was among the more positive, with him saying that he felt that "dialogue has occurred which benefits all". However, in a work attributed to him in 1961, he is quoted as having said: | ||

{{quote|[The] conference was a balancing-act. I had been made a representative for all, but there would be those who I could not represent. I had been told that angry people and their angry views were not welcome at Tacusi. I considered it important, then, that I should go, as one who was not angry. I wonder, though, if the fearful men had been made unwelcome too, could I have justified staying?}} | {{quote|[The] conference was a balancing-act. I had been made a representative for all, but there would be those who I could not represent. I had been told that angry people and their angry views were not welcome at Tacusi. I considered it important, then, that I should go, as one who was not angry. I wonder, though, if the fearful men had been made unwelcome too, could I have justified staying?}} | ||

Among members of the Ashang, however, negative reactions were evident immediately. Many considered it an affront to basic decency that the Ashang was not invited, and protests against the conference occurred in major cities across Naikang, including at [[Tachusi]], where the conference was being held. In the end, however, the conference resulted in the [[Proclamation of Independence of the State of Naikang|Proclamation of Independence]] and the creation of the [[State of Naikang]]. | |||

{{Template:Naikang topics}} | {{Template:Naikang topics}} | ||

Latest revision as of 02:10, 15 October 2023

| Naikangese Civil War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Era of Civil Wars and the collapse of the Riamese Empire | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

Diplomatic support | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

≈###,### (1957) |

≈###,### (1958) | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Naikangese Civil War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Naikang from 7 March 1956 to the Treaty of Bano in August 1971. The war was fought between the State of Naikang (with critical support from Riamo) and the Ashang, with supporting groups on both sides. The war was one of the first wars in the Gulf of Kouma to be widely publicised, with film, news and photographic sources spread throughout Anteria.

With the victory of the nationalist movement in the nonviolent Lotus Revolution, led by the Chengshengese Blue Lotus Party, the State of Naikang became an independent nation in the region, though very soon the Blue Lotus Party established themselves as a dominant party in the fledgeling nation. The Naikanghi Ashang, a political group that had advocated (unsuccessfully) for a wide range of policies for guaranteeing independence for the Naikanghi people, argued for the rights of the Naikanghi minority within the country, and in the wake of the 1956 elections, when anti-Naikanghi corruption was seen as highest, the Ashang declared war on the State.

The following years were marked by increasing authoritarianism within the State of Naikang, as well as numerous human rights violations, acts of genocide and/or brutal massacres. Just over a year after war was declared, General Cheq Iangsu took over the state as its president, passing an emergency powers act to ensure his continued rule over the country. Beginning in September 1963, Gheu Zinzai took over the country in a period of democratisation, and formally disbanded the Blue Lotus party, aiming for unity at any cost, even reconciliation with the Ashang. This period saw a gradual decrease in outright fighting, as well as a warming of relations. From 13 June 1971, the Bano Peace Conference was held to determine the future of a Naikangese nation, with conciliations for each side. Eventually, the current federal situation was adopted, and on 27 August, the Treaty of Bano was signed, bringing an end to the war.

The war's end led to some major demographic shifts, with many ethnic Naikanghi and Chengshengese moving away from areas with a majority of the other ethnicity. The reconciliation period after the war saw changes in laws that aimed to minimise ethnic nationalism and promote unity for the whole country.

Names

Various names have been used for the war. The term Naikangese Civil War is most common in Common, and is thus a common term in Riamo, where most of the international effects of the war were felt. Many veterans of the conflict from Riamo simply refer to it as Naikang or 'Kang. In Chengshengese and Myacha, the common term for the war is the Ashang War. In Naichinese, the war is commonly referred to as the Resistance War, the Resistance or the Second Independence Struggle. The official name promoted by the federal government in Naikang is the War of 1956.

Background

The primary military organisations involved with the war were the State of Naikang Armed Forces, with support from the armed forces of Riamo as well as Myacha paramilitaries, all of whom fought against the Naikanghi Ashang (commonly referred to as the Ashang), a union of various Naikanghi-majority political and military groups.

Naikang had been a Riamese colony prior to its eventual independence. The Great War saw Riamo defeated, and much of its colonial empire stripped away. With difficulty controlling the remaining portions of the Empire, the Nai Kang Independence Front (NKIF), headed by the Blue Lotus Party, began engaging in acts of civil disobedience and political pressure against the colonial government. Some time later, seeing the successes of the NKIF, numerous Naikanghi parties unified to create the Ashang, aiming to put more direct pressure on the colonial government, engaging in small-scale acts of violence and sabotage in order to advocate for the rights of the Naikanghi. While nominally on the same side during the struggle for independence, relations between the NKIF and the Ashang were known to be icy. There were political differences between the groups - the NKIF was largely right wing, and while the Ashang held some centre-right groups within its organisational structure, it skewed far more often to the left - though the main issues came down to the construction of a post-independence state. Members of the NKIF wanted to essentially transform the Riamese colony directly into an independent, unitary state, while the various organisations of the Ashang argued for solutions ranging from devolution of government or a fully-fledged federal system to independence for the Naikanghi portions of the country. There were also issues of racism between the groups. While the two groups never fully came to blows during this period, it was no secret that the Chengshengese saw the Naikanghi as backward savages, while the Naikanghi saw the Chengshengese as historical and continual oppressors.

This state of division only widened when the Riamese government announced a conference in the city of Tatchossey, with the rules for attendance being that individuals attending must not represent any group that has recently encouraged violence against the Riamese colony. The preceding period of peaceful protest and political demonstration conducted by the NKIF proved sufficient to the conference's organisers to permit the NKIF a seat at the table, while the only sanctioned Naikanghi representation were some independents led by Xu Ti Na, a Naikanghi monk who had long advocated for nonviolent protest. In the second week of the conference, the conservative and nationalist Myacha group, the Thunder Dragon Party, were also permitted to sit at the conference.

The fairness of the Tatchossey Conference has been hotly debated in the conference's aftermath. Most of the conference's attendees highlighted that it brought unity to groups which had previously been disparate, and even today, many Chengshengese and Myacha people hold it up as a triumph of ethnic cooperation over mistrust. Among Naikanghi, however, the reaction was almost universally negative. Xu Ti Na's response was among the more positive, with him saying that he felt that "dialogue has occurred which benefits all". However, in a work attributed to him in 1961, he is quoted as having said:

[The] conference was a balancing-act. I had been made a representative for all, but there would be those who I could not represent. I had been told that angry people and their angry views were not welcome at Tacusi. I considered it important, then, that I should go, as one who was not angry. I wonder, though, if the fearful men had been made unwelcome too, could I have justified staying?

Among members of the Ashang, however, negative reactions were evident immediately. Many considered it an affront to basic decency that the Ashang was not invited, and protests against the conference occurred in major cities across Naikang, including at Tachusi, where the conference was being held. In the end, however, the conference resulted in the Proclamation of Independence and the creation of the State of Naikang.