Crovanism: Difference between revisions

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

Crovanism is rooted in the {{wpl|romantic nationalism}} that surged after the [[Ambrosian Revolution]]. Crovan professed being "strongly moved" by the {{wpl|Transcendentalism|Ambrosian Idealist}} movement. However, he appeared to eschew the {{wpl|Individualism|individualist}} undercurrents of the movement in favor of the {{wpl|Old Hegelians|Absolute Idealists}}, particularly {{wpl|Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel|Cuthbert Campbell Brown}} who wrote that "the supreme duty of the individual is to his nation, which is itself the supreme {{wpl|Ideal (ethics)|ideal}}". | Crovanism is rooted in the {{wpl|romantic nationalism}} that surged after the [[Ambrosian Revolution]]. Crovan professed being "strongly moved" by the {{wpl|Transcendentalism|Ambrosian Idealist}} movement. However, he appeared to eschew the {{wpl|Individualism|individualist}} undercurrents of the movement in favor of the {{wpl|Old Hegelians|Absolute Idealists}}, particularly {{wpl|Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel|Cuthbert Campbell Brown}} who wrote that "the supreme duty of the individual is to his nation, which is itself the supreme {{wpl|Ideal (ethics)|ideal}}". | ||

In ''A Treatise on Good Government'', Crovan reiterated much of Campbell Brown's argument, calling nationhood "the ultimate creed towards which, consciously or unconsciously, all men strive. Infinitely more powerful than the abstract notions of avarice, charity, liberty, obedience, it is the driving force in every human experience." Crovan is usually identified with the tradition of {{wpl|civic nationalism}}, promoting the concept of the "the Common Ideal" rather than common ethnic ancestry as the vital component of nationhood. The "Common Ideal" was, in his view, a shared acceptance of legal, political, and cultural norms that was innate to social organization. He held that a nation could only grow as the "Common Ideal" neared "universality"—i.e. growing acceptance by its population. Conversely, those nations fractured by a diversity of acceptable political and legal "ideals" would inevitably wither and collapse at the hands of a stronger one. | In ''A Treatise on Good Government'', Crovan reiterated much of Campbell Brown's argument, calling nationhood "the ultimate creed towards which, consciously or unconsciously, all men strive. Infinitely more powerful than the abstract notions of avarice, charity, liberty, obedience, it is the driving force in every human experience".<ref name="treatise 1">Godfred Crovan, 1856. ''A Treatise on Good Government''. Elsbridge: Harcourt Publishing. p. 232.</ref> Crovan is usually identified with the tradition of {{wpl|civic nationalism}}, promoting the concept of the "the Common Ideal" rather than common ethnic ancestry as the vital component of nationhood. The "Common Ideal" was, in his view, a shared acceptance of legal, political, and cultural norms that was innate to social organization. He held that a nation could only grow as the "Common Ideal" neared "universality"—i.e. growing acceptance by its population. Conversely, those nations fractured by a diversity of acceptable political and legal "ideals" would inevitably wither and collapse at the hands of a stronger one. | ||

Blending the {{wpl|social contract}} theories of [[Bendiktas Klimantis]] and {{wpl|Thomas Hobbes|Edgard Wessex}}, Crovanists argue that, because the state is the natural outgrowth of the people (and thus, the nation), it should be empowered so as to most effectively fulfill the contract. In this sense, they are largely in favor of government centralization rather than decentralization—many influential early Crovanists, including {{wpl|John A. MacDonald|Samuel Gerrish}} and {{wpl|Gideon Welles|Richard Powell}}, were vocal proponents of a {{wpl|unitary}} system during the early years of the Republic. While modern day Crovanism is largely compatible with {{wpl|federalism}}, adherents nevertheless continue to push for a larger, all-encompassing state apparatus as vital in both promoting the ideal of nationhood and addressing its concerns. | Blending the {{wpl|social contract}} theories of [[Bendiktas Klimantis]] and {{wpl|Thomas Hobbes|Edgard Wessex}}, Crovanists argue that, because the state is the natural outgrowth of the people (and thus, the nation), it should be empowered so as to most effectively fulfill the contract. In this sense, they are largely in favor of government centralization rather than decentralization—many influential early Crovanists, including {{wpl|John A. MacDonald|Samuel Gerrish}} and {{wpl|Gideon Welles|Richard Powell}}, were vocal proponents of a {{wpl|unitary}} system during the early years of the Republic. While modern day Crovanism is largely compatible with {{wpl|federalism}}, adherents nevertheless continue to push for a larger, all-encompassing state apparatus as vital in both promoting the ideal of nationhood and addressing its concerns. | ||

===Northumbrian nationalism=== | ====Northumbrian nationalism==== | ||

Though Crovan himself was born into a mixed-race [[Northumbrian people|Northumbrian]] family, he rejected Northumbrian separatism and repeatedly stressed the indivisibility of the Ambrosian nation. Despite historical strife, he considered the union of Harwickers and Northumbrians in one state to be "[[Annwynism|divinely ordained]]". At his inauguration address in 1861, he stated that "I have no use for a government of yellow men, just as I have no use for a government of white men. I can only deliver a government of Ambrosians, for Ambrosians, for I am convinced that our union is the most holy, the most enlightened, the most natural on Earth." Crovan intentionally downplayed his own ethnic identity during his lifetime, and referred to the prominent Northumbrian nationalist [[William Casement]] as "the man most determined to bring about [Northumbria's] downfall since [[Richard the Terrible]]". Rhetorically, his administration was characterized by appeals to inter-ethnic harmony, and he instituted harsh penalties against those espousing {{Wpl|Separatism#Racial separatism|racial separatist}} views. | Though Crovan himself was born into a mixed-race [[Northumbrian people|Northumbrian]] family, he rejected Northumbrian separatism and repeatedly stressed the indivisibility of the Ambrosian nation. Despite historical strife, he considered the union of Harwickers and Northumbrians in one state to be "[[Annwynism|divinely ordained]]". At his inauguration address in 1861, he stated that "I have no use for a government of yellow men, just as I have no use for a government of white men. I can only deliver a government of Ambrosians, for Ambrosians, for I am convinced that our union is the most holy, the most enlightened, the most natural on Earth." Crovan intentionally downplayed his own ethnic identity during his lifetime, and referred to the prominent Northumbrian nationalist [[William Casement]] as "the man most determined to bring about [Northumbria's] downfall since [[Richard the Terrible]]". Rhetorically, his administration was characterized by appeals to inter-ethnic harmony, and he instituted harsh penalties against those espousing {{Wpl|Separatism#Racial separatism|racial separatist}} views. | ||

Despite Crovan's own ethnic | Despite Crovan's own ethnic background, Crovanism has been criticized as an ideology hostile to Northumbrian culture. Some commentators view it as justifying the limitation of Northumbrian cultural expression, including historical bans on Northumbrian {{wpl|Music of Nenetsia|music}}, {{wpl|Tadibya|religious practices}}, and [[Northumbric language|language]]. In the modern day, Crovanists have come under criticism for support of economic policies responsible for {{wpl|climate change}} and land reform, which Northumbrians view as threatening to destroy traditional cultural practices such as {{wpl|reindeer husbandry}} that have existed for centuries. The [[Free Soil Party]], a {{wpl|regionalist}} party based in the Northumberland, is the only major modern [[List of political parties in Ambrose|political party in Ambrose]] that does not claim part of the Crovanist tradition. | ||

===Militarism=== | ===Militarism=== | ||

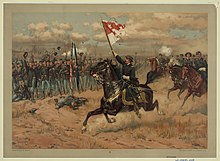

[[File:Sheridan's ride by Thure de Thulstrup 04047u original.jpg|220px|thumb|right|Crovan's military background influenced his stance on militarism]] | |||

Crovan, himself a career soldier, considered militarism one of the supreme virtues of the Ambrosian Republic that set it apart from other representative democracies such as [[Aucuria]] and [[Galideen]]. He believed that the armed forces were the "natural arbiters of social organization", largely due to a perception of the military as an apolitical governmental authority that was solely responsible to the nation, rather than partisan interests. | |||

{{quote|The armed services, thus, may be free to act independently of the petty influences of faction, from the personal ambitions and foibles that are all too common among the legislator or the bureaucrat. They may act, and indeed may ''only'' act, with the interests of the nation in mind. For the soldier's only master is his nation; there is no authority which is predicated on clearer principles than the one that has literally been forsworn with one's life.<ref name="treatise 2">Godfred Crovan, 1856. ''A Treatise on Good Government''. Elsbridge: Harcourt Publishing. p. 304.</ref>}} | |||

Despite arguably ruling as an {{wpl|autocrat}}, Crovan rejected outright {{wpl|military dictatorship}}; after rising to power, he restored limited civilian rule in local and [[Administrative divisions of Ambrose#Thanedreds|thanedred]] governments, and relaxed the government's national restrictions on {{wpl|civil liberties}}. Scholars have speculated that he intended to fully {{wpl|Democratization|democratize}} the country after the conclusion of the [[Great War of the North]]. In his ''Treatise'', Crovan called for the military's role in government to be bound by "strict rules and precedents"; the precise extent of this role however, has been subject to various interpretations by both proponents and critics of Crovanism, ranging from {{wpl|guided democracy}} to {{wpl|stratocracy}}. | |||

The modern-day Ambrosian political system incorporates many aspects of Crovanist militarism: since 1888, four seats of the [[House of Burgesses]] are reserved for active-duty military officers, selected by the Department of War. The Undersecretaries of the Army and of the Navy also must be active-duty officers; this stipulation may terminate the candidacy of a prospective Secretary of War, who is responsible for filling both positions prior to their confirmation. Additionally, the Ambrosian General Staff operates independently of civilian oversight, save the [[President of Ambrose]]. Additionally, two active-duty officers have been freely elected to the position of President: Generals [[Frederic Townsend]] (1935-1941) and [[John Frederick Cleburne]] (2013-present). | |||

===Republicanism=== | ===Republicanism=== | ||

===Populism=== | ===Populism=== | ||

Revision as of 21:17, 23 October 2019

Crovanism, also termed Crovanic democracy, is a Nordanoconitian political philosophy based on the writings and policies of Field Marshal Godfred Crovan, who served as President of the Ambrosian Confederal Republic from 1858 to his death in 1865. Doctrinally it is characterized by a democratic framework maintained through military support, with emphasis on populist, progressive social policies and centralized authority rooted in a charismatic leader. Crovanists may also hold interventionist outlooks in foreign policy, though this is less universally prevalent.

The movement has been a major player in Ambrosian politics since the mid-19th century. Today, the Conservative Party of Ambrose officially considers Crovanism a central tenet of their ideology; other major parties such as the Reform and Union Labor Parties espouse various aspects of Crovanism to differing degrees. In other Nordanian countries, particularly Sjealand and other NOSDO member-states, the movement is highly controversial due to its association with Ambrosian imperialism; however it enjoys limited mainstream popularity in Cradebetia and Swastria.

Crovanism has been the subject of both praise and criticism from political thinkers across the spectrum. Adherents claim to be the heirs of an evolved democratic tradition that began with the Ambrosian Revolution; indeed, during the Great War of the North Crovan characterized his regime as a bastion of democracy, standing against the autocratic monarchies of Nordania. Critics, however, contend that the ideology rejects the classical liberalism central to the revolution, and instead label it as a form of managed republicanism; Charles-Jérôme Persigny called it "an erosion of liberal democracy by martial rule", while Jigór Małinowski labelled it "a demagogic charade [perverting] popular sovereignty by masking reactionary anocracy with half-hearted reforms and pretensions."

Prominent modern-day Crovanists include John Frederick Cleburne, incumbent President of Ambrose, and Agueybana Humacao of Capantan.

Components

Nationalism

Crovanism is rooted in the romantic nationalism that surged after the Ambrosian Revolution. Crovan professed being "strongly moved" by the Ambrosian Idealist movement. However, he appeared to eschew the individualist undercurrents of the movement in favor of the Absolute Idealists, particularly Cuthbert Campbell Brown who wrote that "the supreme duty of the individual is to his nation, which is itself the supreme ideal".

In A Treatise on Good Government, Crovan reiterated much of Campbell Brown's argument, calling nationhood "the ultimate creed towards which, consciously or unconsciously, all men strive. Infinitely more powerful than the abstract notions of avarice, charity, liberty, obedience, it is the driving force in every human experience".[1] Crovan is usually identified with the tradition of civic nationalism, promoting the concept of the "the Common Ideal" rather than common ethnic ancestry as the vital component of nationhood. The "Common Ideal" was, in his view, a shared acceptance of legal, political, and cultural norms that was innate to social organization. He held that a nation could only grow as the "Common Ideal" neared "universality"—i.e. growing acceptance by its population. Conversely, those nations fractured by a diversity of acceptable political and legal "ideals" would inevitably wither and collapse at the hands of a stronger one.

Blending the social contract theories of Bendiktas Klimantis and Edgard Wessex, Crovanists argue that, because the state is the natural outgrowth of the people (and thus, the nation), it should be empowered so as to most effectively fulfill the contract. In this sense, they are largely in favor of government centralization rather than decentralization—many influential early Crovanists, including Samuel Gerrish and Richard Powell, were vocal proponents of a unitary system during the early years of the Republic. While modern day Crovanism is largely compatible with federalism, adherents nevertheless continue to push for a larger, all-encompassing state apparatus as vital in both promoting the ideal of nationhood and addressing its concerns.

Northumbrian nationalism

Though Crovan himself was born into a mixed-race Northumbrian family, he rejected Northumbrian separatism and repeatedly stressed the indivisibility of the Ambrosian nation. Despite historical strife, he considered the union of Harwickers and Northumbrians in one state to be "divinely ordained". At his inauguration address in 1861, he stated that "I have no use for a government of yellow men, just as I have no use for a government of white men. I can only deliver a government of Ambrosians, for Ambrosians, for I am convinced that our union is the most holy, the most enlightened, the most natural on Earth." Crovan intentionally downplayed his own ethnic identity during his lifetime, and referred to the prominent Northumbrian nationalist William Casement as "the man most determined to bring about [Northumbria's] downfall since Richard the Terrible". Rhetorically, his administration was characterized by appeals to inter-ethnic harmony, and he instituted harsh penalties against those espousing racial separatist views.

Despite Crovan's own ethnic background, Crovanism has been criticized as an ideology hostile to Northumbrian culture. Some commentators view it as justifying the limitation of Northumbrian cultural expression, including historical bans on Northumbrian music, religious practices, and language. In the modern day, Crovanists have come under criticism for support of economic policies responsible for climate change and land reform, which Northumbrians view as threatening to destroy traditional cultural practices such as reindeer husbandry that have existed for centuries. The Free Soil Party, a regionalist party based in the Northumberland, is the only major modern political party in Ambrose that does not claim part of the Crovanist tradition.

Militarism

Crovan, himself a career soldier, considered militarism one of the supreme virtues of the Ambrosian Republic that set it apart from other representative democracies such as Aucuria and Galideen. He believed that the armed forces were the "natural arbiters of social organization", largely due to a perception of the military as an apolitical governmental authority that was solely responsible to the nation, rather than partisan interests.

The armed services, thus, may be free to act independently of the petty influences of faction, from the personal ambitions and foibles that are all too common among the legislator or the bureaucrat. They may act, and indeed may only act, with the interests of the nation in mind. For the soldier's only master is his nation; there is no authority which is predicated on clearer principles than the one that has literally been forsworn with one's life.[2]

Despite arguably ruling as an autocrat, Crovan rejected outright military dictatorship; after rising to power, he restored limited civilian rule in local and thanedred governments, and relaxed the government's national restrictions on civil liberties. Scholars have speculated that he intended to fully democratize the country after the conclusion of the Great War of the North. In his Treatise, Crovan called for the military's role in government to be bound by "strict rules and precedents"; the precise extent of this role however, has been subject to various interpretations by both proponents and critics of Crovanism, ranging from guided democracy to stratocracy.

The modern-day Ambrosian political system incorporates many aspects of Crovanist militarism: since 1888, four seats of the House of Burgesses are reserved for active-duty military officers, selected by the Department of War. The Undersecretaries of the Army and of the Navy also must be active-duty officers; this stipulation may terminate the candidacy of a prospective Secretary of War, who is responsible for filling both positions prior to their confirmation. Additionally, the Ambrosian General Staff operates independently of civilian oversight, save the President of Ambrose. Additionally, two active-duty officers have been freely elected to the position of President: Generals Frederic Townsend (1935-1941) and John Frederick Cleburne (2013-present).

Republicanism

Populism

Interventionism

List of Crovanist political parties

Please feel free to add your own political parties to the list, in alphabetical order.

✝ indicates a party that is currently defunct

Ambrose

Ambrose

Swastria

- Free Conservative Party✝

- National Liberal Party[3]

- National People's Party[3]

- Swastrian People's Party✝