Menghean famine of 1985-87: Difference between revisions

m (1 revision imported) |

Latest revision as of 17:07, 11 March 2019

The Menghean famine of 1985-87, domestically known as the Three Years of Hardship (고난의 3년, gonan-e sam nyŏn) and sometimes as the Ryŏ Ho-jun Famine (려호준 기근, Ryŏ Ho-jun gigŭn), was a famine that took place in Menghe during the years 1985 through 1987. It was most pronounced in the country's southern region, especially the provinces of Chŏnro, Hwangjŏn, Sanchŏn, and Uzeristan, and its effects were also felt elsewhere in the country. The proximate cause of the famine was a severe drought, brought on by the El Niño cycle of 1985-87, but it was intensified by the government's policy decisions, including agricultural collectivization, inefficiencies in the distribution of relief, and sanctions against the country's secret nuclear program.

Menghe's current government, led by Choe Sŭng-min, came to power in a coup motivated in part by the famine, and has fiercely opposed all cover-up efforts by former MPCP officials. Nevertheless, due to inconsistent record keeping in the wake of Ryŏ's "perpetual revolution," there is still disagreement over the exact death toll. Official figures endorsed by the current government lie at around 10 million deaths due to starvation; estimates produced by international organizations range from 200,000 to 35 million.

Background

Earlier agricultural organization

While certain members of the Menghean People's Communist Party had vowed during the Menghean War of Liberation to abolish the private ownership of land, upon coming to power they adopted a more moderate approach. Sun Tae-jun, the General-Secretary through the 1960s, instead decided to implement straightforward land reform, breaking up the large agricultural estates established under the Occupation and Republic periods and dividing the land into small plots for individual households. The Menghean Liberation Army had already carried out land redistribution while retaking territory during the war, a major source of its popularity among the general population.

Sim Jin-hwan, in his ambitious campaigns to import heavy industry, toyed with the idea of collectivization in his early years as General-Secretary, but ultimately decided that it would be impractical to implement it across the country and instead focused on developing the cities. Under his leadership, some localities organized "industrial farms" spanning large areas of land and employing locals as laborers, but these were relatively uncommon, and were mainly established on new or reclaimed land rather than atop existing villages.

Collectivization

Ryŏ Ho-jun, who came to power in June of 1980, sought to change course. Denouncing Sim's industrial farms as "agrarian state capitalism" and the redistributed small plots as a holdover from the Feudal age, Ryŏ decided in 1981 to convert to collective agriculture.

Initially, Ryŏ and his Populist faction (Minjungpa) believed that collectivization would unfold naturally, as peasants enlightened by Party speeches recognized collectives as a liberating form of agriculture. Actual implementation, however, was slow, and by February of 1982 only 10% of the country's land was organized into collectives.

Blaming the slow uptake on "obstruction by revisionists [i.e., members of the pro-Sim Progress faction]," Ryŏ decided to act more forcefully. He identified collectivization as one of the major goals of his perpetual revolution, but held off on implementing it until the winter of 1982-1983 so that he could first deal with his political opponents. When collectivization did come, it was swift and forceful; tens of thousands of Red Pioneers were sent to the countryside to persuade peasants to collectivize, a process that often involved violence and intimidation. By the end of 1983, perhaps 40-50% of the country's agricultural land had been collectivized.

Famine of 1983

The abrupt shift to collectives was followed by a 17.2% decline in agricultural output, according to official figures (which were generally unreliable). Collective workers were "underpaid, underfed, and unmotivated," in the words of one writer, and many refused to work under the new system, comparing it to the consolidated estates of the Occupation era. The perpetual revolution had also disrupted Menghe's transportation system through the arrest of railroad staff and the use of trains to move Red Pioneer units; survivors later recalled seeing heaps of vegetables or meat piled up beside train stations for weeks on end, often under armed guard.

Overall, the famine of 1983 was relatively minor, but only in comparison to what was to come. Post-1988 estimates determined that 200,000 to 400,000 people died of hunger in 1983 and early 1984, most of them in the inland provinces. Favorable weather cushioned the effect of collectives' inefficiency, and in areas where transportation failed, local villagers often found ways to smuggle out stored grain. Rationing in the cities, however, reached its peak level, and the year 1983 is widely remembered as a precursor to future hardship.

Accelerated collectivization

After falling in 1983, harvests appeared to rise again in 1984. Whether they actually did rise has been debated; some historians attribute the change to enthusiastic reporting or self-preservation among village officials reporting figures, while others find signs of a small recovery. Whatever the case may be, this came as a sign of relief to Ryŏ and his Populist faction, who promptly used it to argue that while the disturbance of collectivization might initially lead to a fall in output, in the long run collectives would produce more than feudal farms "due to the liberated enthusiasm of the workers."

For this reason, central planners chose 1985 as the year in which collectivization would be extended to the whole country - or at least, as much of the country as possible. This time, Red Pioneers bound for the countryside were joined or followed by agents of the Ministry of State Security, as an added measure against any "old-minded reactionaries" who resisted the confiscation of land. By the end of the year, over 80% of land was collectivized; reliable figures are impossible to find for the two years that followed.

Nuclear testing and embargo

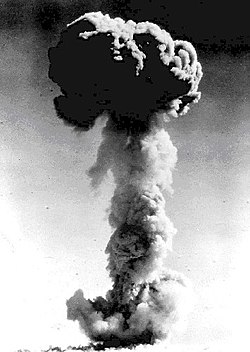

The third proximate cause of the 1985-87 famine was also political. On November 4th, 1984, Menghe detonated a 2-kiloton nuclear device at Naran Gacha in the Sŏsamak desert, the first above-ground nuclear test in twenty years. In a bellicose statement that followed, Ryŏ Ho-jun threatened a first strike on Dayashina, and announced plans to develop missiles capable of hitting the Organized States.

Under the terms of the STAPNA agreement, all other signatories, making up nearly all countries in the world, placed Menghe under a strict embargo until it agreed to nuclear disarmament - a policy which Ryŏ staunchly opposed. Boasting of Menghe's capacity for self-reliance, he vowed to continue with the nuclear program until the core nuclear powers agreed to host a revision of STAPNA, something at which all countries balked.

On November 29th, 1984, all imports to Menghe, including imports of food, ceased. From that point onward, neither international trade nor foreign relief would be available.

Timeline

1985

1985 turned out to be a poor year for agricultural reform. The El Niño of 1985-1987, which nearly coincides with the period of severe famine, was a particularly severe one in East Hemithea, described by some meteorologists as a "hundred-year event." Menghe's climate, especially in the south, is heavily influenced by the monsoon cycle, with relatively dry winters and a period of heavy rain in the summer as the intertropical convergence zone drifts north and draws in humid air from the South Menghe Sea. During an El Niño cycle, however, the shift of the ITCZ is less pronounced, and the heavy storms they bring take place further south, over the open ocean.

What this means in practice is that the summer rains, a reliable and necessary source of water on the southern plain, can arrive intermittently or cease altogether, as they did in 1985. In his journal, a military official in Chŏnro Province described "a completely cloudless blue sky, utterly bare, like an empty rice bowl inverted over the world... in spite of the summer heat, it made the world feel cold... grass dried up and trees shriveled, as though it were already November." By August, it was immediately apparent that crops in the hardest-hit areas would be lost before harvest.

To his credit, when news of the first drought arrived, General-Secretary Ryŏ did make an effort to organize food aid. Surplus grain from the east coast, which was less hard-hit, would be shipped west to the southern plain and the Haesŏ region. Yet for a variety of reasons, long-distance food aid did not materialize. The train network was struggling with embargo-related fuel shortages, and commune leaders in the East could only dispatch grain for relief after they had surpassed their quotas for local production - and few did.

On hearing that relief was delayed, Ryŏ ordered the Red Pioneers to take charge of food distribution in drought-stricken areas. Reviving rhetoric brought out during 1983, he blamed the shortages on traditionalist peasants and speculators, whom he accused of selfishly hoarding grain. Red Pioneer "popular action units," most of them brought in from the cities or other areas of the country, stormed through villages, confiscating any stockpiled grain they could find and bringing it to county governments. In many cases, eager to meet their own quotas, they confiscated seeds kept for next year's planting, as well as any livestock which individual households had retained after collectivization.

The grain confiscations sparked resentment and confrontation around the country, but especially in the southern plain and Haesŏ region. Once county governments received confiscated food, they distributed rations to soldiers, Party members, and Red Pioneers first, only later sending it to commune canteens - and when it arrived there, only villagers who had met their own production quotas had enough ration cards to buy it. Reports of deaths from starvation began filtering up through the ranks of administration.

1986

By the following spring, it was already clear that the crisis would only grow worse. All weather data pointed to another year of drought, possibly a more severe one. Moreover, the share of land actually under cultivation had dropped: many peasants were too hungry to tend to the fields, and there was precious little seed grain remaining. Party members, including allies of the Minjungpa faction, began writing impassioned letters to the upper leadership, describing the state of the crisis and demanding real solutions - organized redistribution, foreign aid in exchange for nuclear disarmament, even a return to household farming.

These complaints terrified Ryŏ more than news of the famine did. Fearful of a within-Party uprising against his authority, he tightened his grip on the Central Committee, silencing any voices of opposition. Then, on May 23rd, he issued a "Central Notice" to the general public. In it, he acknowledged that there had been food shortages the preceding year, but attributed them to backward-thinking peasants, reiterating the (dubious) statistic that yields had dropped in 1983 and recovered in 1984. On that basis, he argued, with enough hard work the peasantry could overcome the current shortage and surpass the 1982 harvest - and for that reason, famine relief of any kind was unnecessary and would not be provided.

In Chŏnro Province, the famine relief of the preceding year, while meagre, had at least kept the population strong enough to resist - and resist they did. Just days after the Central Notice was published, local Party officials reported riots across the drought-hit areas, with peasants storming the communal granaries and distributing last year's stored rice. In at least a dozen counties, they broke into militia stockpiles and armed themselves with automatic rifles. Resistance in Haesŏ was more muted, as the initial famine had struck harder there, but it was sufficiently strong to disrupt mining in the coal-rich area.

Most of these riots and rebellions were entirely spontaneous, with no clear leadership or motive even within individual villages; one particularly large militia force, inspired by legends of 12th-century resistance to Sunghwa Dynasty misrule, gathered around a self-appointed "warlord" and marched on the county seat, but most were only concerned with seizing food in their own villages. To Ryŏ Ho-jun, however, the uprisings confirmed his worst fears: blaming them on reactionary agents and foreign spies, he ordered the Menghean People's Army to suppress them immediately.

The commander of the Southern Military District, General Chang In-su, refused to carry out the order; Gang Byŏng-chŏl, the ruling Premier, had him arrested for insubordination, and passed on command to Lieutenant-General Gwak Gi-yŏng. The initial crackdown was accomplished in less than two weeks, with half of that time spent mobilizing the necessary forces. Although the summer and fall to follow would bring the highest number of famine deaths, from that point onward the rural population was either too weak or too terrified to resist in force.

Ryŏ and Gang, who at this point were governing as a pair, did not see it that way. Fully attributing shortages to domestic and foreign saboteurs, they ordered a new round of emergency measures to confiscate hidden grain, and began imposing collective punishment against any village that fell below its grain quota. Motivated by a hunt for class enemies and a ten percent share of any food they found, Party activists swept through the countryside in an even more brutal way than they had last year. From this point onward, invoking the danger of rebellion and invasion, Ryŏ and Gang relied on the Ministry of State Security; the Red Pioneers, who by now had seen emaciated peasants with their own eyes, could no longer be trusted. Indeed, during the summer of 1986, the "perpetual revolution" gradually ground to a halt.

1987

By the winter of 1986-87, the situation was dire. Estimated rice harvests in late 1986 were less than half of their normal level, even lower in the south and west. Confiscation continued, but food distribution ground to a halt. Countless reports emerged that villagers were eating anything they could get their hands on - grass, tree bark, spoiled sweet potatoes, various wild plants, even birds and mice if they could catch any. More troubling reports attested to cases of cannibalism.

The year 1987 also saw the most striking neglect by Party officials. Ryŏ Ho-jun continued hosting lavish banquets for his friends and allies, at one point staging propaganda photographs of the proceedings to prove that the famine had come to an end. Across the country, Party members and nuclear scientists were given preferential access to food, in implicit exchange for their continued loyalty. Official policies also reserved set quotas of rice and meat for Army personnel, though in practice rations for individual soldiers fell below the nutritional minimum and military units were expected to set up communes of their own outside their bases.

In the hardest-hit areas, extreme hunger gave way to despair or resignation. A visitor to Andong-ri, just a few dozen kilometers east of Insŏng, wrote of "hundreds of victims, not even recognizably human, like skeletons or ghosts... they were too tired to even beg, many lay in their own homes waiting for death... corpses lined the roads, sometimes sitting for days, as the survivors limped over them... there were probably more dead than alive." Scenes in the center-north could be even starker. In the absence of food and medical care, disease set in, accounting for perhaps half of the overall death toll.

While in the first two years famine was mostly limited to the Chŏnro and Haesŏ regions, by 1987 hundreds of thousands and perhaps millions of internal refugees had flocked to the country's cities and to the eastern region, where weather had remained more stable and food was readily available. State Security Forces attempted to restrain the flow of migrants, fearing it would disturb political stability, but other individuals in the vast state bureaucracy offered them shelter or protection, either due to kinship ties or general sympathy. By the end of the year, large crowds of famine survivors had settled in public spaces across the country, most notably in the capital, Donggyŏng.

Effect on regime change

In the early morning hours of December 21st, 1987, Major-General Choe Sŭng-min led his troops into the heart of Donggyŏng, allegedly after receiving orders to carry out a massacre against hungry migrants and urban protesters gathered in People's Square. Instead of following those orders, Choe launched an attack on the Party headquarters hall and sent troops to secure radio stations and government buildings around the city. By noon on the following day, the coup was complete, and the Menghe People's Communist Party had been removed from power.

In a speech from the steps of the Donggwangsan palace, and later a televised statement broadcast on state television, Choe listed the MPCP's cruel response to the famine as his leading motivation for taking power. Soon afterward, the Interim Council for National Restoration signed an agreement to scrap the country's nuclear arsenal and open the borders to international aid organizations. Complicity in the famine was a prominent theme in [[Ryŏ_Ho-jun#Final_years|Ryŏ Ho-jun's show trial}}, at times eclipsed by his role in political purges against his opponents. Official histories by the Menghe Socialist Party have largely remained true to this narrative, emphasizing the hardship of the famine as justification for Choe's decision to seize power, and contrasting rural poverty in the 1980s with economic development in the decades that followed.

Dissidents living abroad have contested this account, arguing that the coup conspirators exaggerated the importance of the famine in subsequent accounts in order to gain more legitimacy for their seizure of power. In particular, many note that the seizure of power took place two and a half years after the first signs of famine became apparent, and six years after the precursor famine associated with the collectivization campaign. Thomas Lee, a prominent figure in the Menghean government in exile, noted in a 2006 speech that "when the [Communist] Party destroyed the factories, or purged the moderates, or brought about the famine, the nationalists in the Army did nothing. Only when the Party threatened to deprive them of their jobs and pensions did they take up arms 'in the name of the people' to put themselves in charge."

Other critics have noted that while the Choe regime openly denounced the famine, it did not make an organized effort to hold the local officials behind it accountable, allowing many of them to remain in their positions as long as they vowed loyalty to the new leadership. The trials which did happen in the late 1980s and early 1990s were usually brief and politicized, targeting only individuals who had opposed Choe or presented themselves as rivals. Similarly, there is still debate over the extent to which Army troops were involved in the suppression of rice rebellions, and the commanding officers involved.

Death toll

After the Socialist Republic of Menghe was officially formed in May 1988, the new government ordered an investigation into the causes and extent of the famine, and declared that all demographic records would be made open to the public. Early speeches by leading politicians exaggerated the cost of the famine, regularly citing death tolls as high as 20 and 25 million in order to justify the coup and emphasize the need for agricultural reform.

The Menghe Socialist Party's official fact-finding investigation, published somewhat hastily in 1990, concluded that "slightly upwards of 10 million people died as a direct result of starvation or due to starvation-related problems, including illness due to enfeeblement." Additionally, it used census birth data to determine that collectively, parents had foregone an additional 10 million children during the three famine years. Subsequent enumerations by state bodies have narrowed the death toll to 11.2 million, which remains the official state figure.

Even without ongoing state efforts to conceal the scope of the famine, however, establishing a reliable death toll remains difficult. From 1981 onward, rural doctors in the Democratic People's Republic of Menghe were forbidden from listing starvation or malnutrition as the cause of death on death certificates, making it difficult to separate famine deaths from other forms of elevated mortality. During the chaos of the "perpetual revolution" and the crackdown on peasant insurrections, detailed and credible record-keeping all but disappeared: both births and deaths went unreported, and deceased individuals were sometimes erased from the existing record.

The greatest disagreement concerns the meaning of the "missing triangle" in contemporary census data, pictured at upper right. Beginning in 1976, the number of surviving individuals with that birthyear steadily declines, until returning to a peak of 11 million in 1989. The total area of the missing section is roughly 35 million persons, corresponding to those who were 10 or younger (and therefore the most at-risk) during collectivization and famine. This figure has been cited by both current regime supporters and foreign critics to claim that the true death toll may have been as high as 70 million once adults are factored in. Most credible demographers have dismissed the 70 million figure as extrapolation, partially attributing that the decline in fertility during the late 1970s to Sim Jin-hwan's birth control programs and to families' decisions to have fewer children in times of hardship, but in light of poor recordkeeping in birth and death certificates, it is difficult to distinguish foregone children from those who died - or were killed by their parents - shortly after birth.

Long-term effects

By the time international food aid arrived, many famine survivors were severely emaciated, and required direct medical care before they could eat solid food again. A large number required psychological treatment. Later in life, members of this generation were at higher risk for chronic health problems.

Concerned that many villages lacked a physically fit labor force to sow the fields, the new government dispatched military brigades to take over planting and harvesting in 1988. With the help of aid workers, the government purchased draught animals and mechanized farm equipment from the east coast and distributed them to recovering areas.

The famine also had a lasting impact on Menghean demography. The dip in children born 1980-1987, a result of foregone children and early deaths, had a lasting effect on schooling and the labor force down the road; by 2005, when this cohort reached the age of 18, the Menghean Army experienced a shortage of conscripts at the same time it was expanding its forces to confront Maverica. In the five years after the famine, hospitals recorded a surge in births, as rural families in particular sought to recover. The 2015 census counted 11,061,230 individuals who were born in 1989, an all-time high.

In the hardest-hit regions, the effects described above were especially severe. In South Chŏnro, which hosted some of Menghe's first special economic zones, voluntary migration made up for the population deficit. In the Southwestern provinces, which were the most neglected, the government offered financial incentives for resettlement, attracting an influx of ethnic Meng to areas once predominantly populated by regional minorities. Upper Chŏnro and Haesŏ never fully recovered, and in the decades to come, millions more would leave to seek better work in the coastal cities.

The drought in other countries

Maverica

Maverica shares with Menghe the monsoon-dependent humid subtropical climate of the South Hemithean Plain, and it was equally hard-hit when the monsoon rain failed in 1985 through 1987. In terms of rainfall, the drought in eastern Maverica was actually more severe than the drought in Menghe, causing unprecedented crop losses.

Unlike Menghe, however, Maverica had been undergoing opening-up reforms, and in 1985 it welcomed relief organizations and food imports from capitalist countries. Maverica's communist leadership had also refrained from collectivizing agricultural land: small household farms remained the norm throughout this period. Mandated sales of grain to the state had been in effect during the preceding years, but the availability of imports and foreign credit allowed the government to relax this requirement and lift it altogether in the east during 1986 and 1987. For these reasons, deaths due to starvation in Maverica were relatively rare during the late 1980s, though still higher than normal.

Innominada

As the southernmost country on the continent of Hemithea, Innominada experienced the least destructive climate effects; the southerly ITCZ rains fell directly on the country in 1985 and 1987, bringing floods, but only 1986 brought drought. As in Maverica, the country remained open to international aid and conventional imports, and no famine as such was reported.

Polvokia

The actual drought in Polvokia was less severe, but the southerly El Niño cycle brought longer, colder winters in 1986-87 and 87-88, which interfered in the spring harvest (the main staple crop in Polvokia is winter wheat). Famine never reached the same extent it did in Menghe, but rationing in the cities and the loss of herds in nomadic areas contributed to a civil war in 1990.