K'uy Dynasty

Chaan K'uy Nimja | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 304 - 895 | |||||||||||

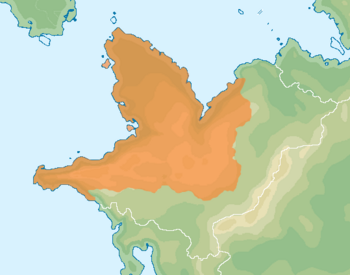

A map of the K'uy Mutul at its greatest extend | |||||||||||

| Capital | Danguixh Uaxakatz'am | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Classical Mutulese | ||||||||||

| Religion | White Path | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| K'uhul Ajaw | |||||||||||

• 304 - 326 | Yax Nuhn Ahin | ||||||||||

• 326 - 353 | Siyaj Chan K’awiil | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

| 304 | |||||||||||

| 895 | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The K'uy Dynasty (Mutli: K'uy Nimja) was the third dynasty to rule the Mutul uncontested. It was preceded by the period of civil war known as the War of the Princes and was followed by another period of internal turmoil: the Cousins War. The K'uy were the first dynasty of foreign origin to conquer the Divine Kingdom and had an important impact over the Mutul's culture. They introduced religious elements such as the Feathered serpent, architectural practices like the talud-tablero, and urbanism as it was practiced in Danguixh.

The K'uy Dynasty was plagued by internal instability. The main divide line of its early history was between the Tatinak aristocracy in Danguixh and the Tatinak-Mutulese aristocracy in Uaxakatz'am which had adopted many aspects of the Chaan culture. Later on, it's the Kayamuca Empire aggressive expansion which would prove to be the main threat to K'uy rule. Despite its apparent long lifespan, the Dynasty can be divided into five lineages: the K'uy, Tzamk'uy, Nehn, Oxk'uy, and Chank'uy. All claimed to be direct descendents of Jatz'om K'uy, last ruler of the Chik'in Kingdom and mastermind of the conquest of the Mutul.

History

Jatz'om K'uy was the mysterious ruler of Danguixh, then known as Tullan-Puh. Historical records and chronicles paint him as the God-king of the city, but don't match historical evidences which tend to show the city as being ruled by an impersonal religious oligarchy, with very few leading figures known by names. Modern historians have proposed the theory that Jatz'om K'uy might have been a dictatorial figure, who took power either through plotting or by force, and became the de-facto lord of the Chik'in Kingdom. it was also said that Jatz'om's mother was of Mutulese origin, being the daughter of the Tzib’ajab K'uhul Ajaw, a claimant to the title of K'uhul Ajaw following the downfall of the Chaan Dynasty. Tzib'ajab had become a tributary state of Tullan-Puh, but revolted sometime during Jatz'om Kuy's rule, which prompted the latter to invade the state, sacrifcing the "Western Pretender", and then proclaiming himself K'uhul Ajaw. Then, a faction of aristocrats from Yux, the old capital of the Chaan, asked for his help in overthrowing the current ruler of the city. A successful campaign led by Jatz'om K'uy most trusted general, Siyaj K’ak, allowed the Tatinak lord to install his son as the new Ajaw of Yux. The "Door of the East" now open to the Tatinaks, Jatz'om K'uy was free to press his claim on all the other successor-states of the Chaan Mutul.

Jatz'om K'uy died before he could rule a truly unified Mutul and its his son, Yax Nuhn Ahin, who would oversee the last few conquests.

Yax Nuhn Ahin returned to Danguixh following his father's death and divided his empire among his generals and family members. His rule was dominated by the figure of the K'aloomte' (High General) Siyaj K'ak, who had been Jatz'om K'uy most trusted general and the one who conquered Yux. Siyaj K'ak had been rewarded, beyond his position in the court as de-facto Prime Minister, with the Ajawil of Waka. His brother, Siyaj Chan K’inich, would become the main teacher and regent of Yax Nuhn Ahin's son: Siyaj Chan K'awiil in his capacities of Ajaw of Yux and Izapak. For his services, Siyaj Chan K'inich was rewarded with Izapak after his pupil rose to the throne, and the city remained in the possession of his family thereafter.

Tz'amk'uy Lineage

Kan Ak Tz'am was the third ruler of the K'uy Dynasty. He began his rule in 353 in Tullan-Puh but on February 1rst 357 (LC: 8.16.0.0. /8 Kankin / 3 Ajaw), exactly 60 years after Jatz'om K'uy declared himself K'uhul Ajaw, he proclaimed the foundation of a new lineage, the Tz'amk'uy. He also began alternating capitals every nine months between Tullan-Puh and Uaxakatz'am, a new settlement he had built. Tullan-Puh remained the main capital of the Mutul only to appease the Tatinak aristocracy, as he was very sympathetic to the Mutulo-Tatinak and to the Mutulese culture as a whole. He notably stopped representing himself in Tatinak clothes and adopted more Mutuleses customs.

His son, B'alamb Jolom, continued the tradition of alternating capitals. His rule (from 373 to 395) is often described as an artistic golden age, but remained politicaly in the continuation of what his father had laid down, including the continuous growth of the Mutulo-Tatinak aristocracy. Because he didn't had any son, powers went to one of his daughters, Ix Wakchan, who had first ruled under the regency of K'aloomt'e B'alamb, an important general of Mutulese origin.

Ix Wakchan's rule was when the divide between the two capitals reached its paroxism: she had been chosen as K'uhul Ix Ajaw without the participation of Tullan-Puh, K'aloomt'e B'alamb was the figurehead of the Mutulese faction, and her court had been filled with partisans of K'aloomt'e and courtisans of Mutulese, or at least Mutulo-Tatinak, descent. Once Ix Wakchan became an adult, she married her regent's nephew, Tz’unun Ich’ak. Her rule was long, her government famed for its fairness, and her authority was uncontested even by the Tatinak aristocracy. But beside this period of relative peace and prosperity for the Mutul, court intrigues had also reached their paroxism. For example, Tz'unun Ich'ak had two of his cousins executed and potentially a third one murdered, for being potential threats to his own power and secure the influence of his lineage.

When Ix Wakchan died in 454, she only had three of her daugthers still alive to inherit her position. Her husband was distrustful of them, and would have prefered that his very young grandson, Muwan Nikte, take the throne so he could maintain his power over the court as regent. But before the eldest of his daughter could take the throne and oppose him, he decided to proclaim himself as K'uhul Ajaw, sparkling a civil war. He was captured and ritually sacrificed in 462, after 7 years of conflict. Ix K'ab, the new K'uhul Ajaw, nonetheless tried to have her nephew executed to secure her position but Muwan Nikte managed to escape and fled to the eastern regions, establishing his own capital in Kajaka and continuing the civil war until 470 when his own partisans betrayed him and delivered him to Ix K'ab to be sacrificed. Ix K'ab died the following year and its her son, Wak Chan K’awiil who inherited the title of Divine Lord unopposed.

Wak Chan K’awiil returned to the old tradition of changing capital every nine months. His rule saw a temporary rise in influence for the Tatinak aristocracy, a tendency continued under his son Wak Chan K'awiil II who certainly planned to move back the capital to Danguixh permanently. But the Maize Bread Insurrection of 515 forced him to flee the Tatinak city back to Uaxakatz’am where he was deposed and sacrificed after a palace coup of the Tatinako-Mutulese Aristocracy. In his stead, they placed his brother: K'inich T'e.

Chank'uy Lineage

K'inich T'e rule is mostly remembered for his gestion of the Maize Bread Insurrection through nation-wide Price controls, recordings of the quantities of grains and tubers circulating on the markets, and massive state-buy or requisitions of these products in regions spared by the droughts so they could be distributed in the most-affected provinces, such as Danguixh and the Yajawil of Kanol. He also encouraged migration and clearing of the borderlands, to reduce the pressure on said affected provinces. This active policy of the government was celebrated by K'inich T'e partisans, but heavily critcized by farmers and traders, the latter demanding a return to a purely demand and supply system without such heavy state interventionism and the former being deprived of a large share of their income, which could be devastating for small landowners. K'inich T'e policy is sometime credited for the growth acceleration large agricultural domains knew at the time, buying or occupying the land abandoned by farmers who could no longer afford them, even after they had sold some of their children to slavery, and ultimately themselves in many cases.

The two successors of K'inich T'e had to face another crisis, in the form of the Mixutz Plague. K'inich Muwaan Jol I died because of the spread of the disease in 556, after only 10 years of rule and the throne went to his brother, who also took the name of K'inich Muwaan Jol II. Like his father before, his rule was characterized by an active gestion of the crisis, with quarantines, the erection of "Healing Stones" and temple-hospitals, and multiple wars at the borders to capture more slaves. Most of these slaves were then mass-sacrificed in an attempt to win back the protection of the gods against the forces of Xibalba but a large portion were instead sold to large landowners, giving them a slight edge once more and further reinforcing them even if many historians have come to contest this interpretations, showing that this influx of slaves was not large enough to influence the income of their masters as a whole. Once again, K'inich Muwaan Jol II interventionism was hotly contested during his lifetime, which led to a serie of minor revolts and insurrections. He died in 571.

Nuhn Ujol Ch'ak rule was 22 years of peace and recovery after the tumultuous reigns of his father, uncle, and grandfather. He mostly left his mark on the Mutul through large architectural works he ordered in various cities of the Divine Kingdom, including temples, observatories, and ball courts. He was content abandoning the interventionist policies of their predecessors and only waging small wars against the other kingdoms to their south and east, as a way to gain tributes and slaves. The long reign of his son, Jasaw Chan K'awiil I, is considered to be the summit of the K'uy Dynasty. He died in 645, after 52 years of rule.

Kayamuca Wars

But the 7th century also saw the rise of a new threat to the Mutul: the Kayamuca Empire. Created in 632, it would expand quickly from modern Ayeli, conquerring entire regions to the east of the Divine Kingdom and establishing colonies in Norumbia. Under the rule of Yik'in Chan K'awiil, in 702, the Lenca peoples that had remained independent on the eastern fringe of the K'uy hegemony pledged alliegeance to the Kayamucans and encouraged other tribes in the K'uy sphere to do the same. This led to the Lencas Wars. Yik'in Chan K'awiil died of old age in 717, and his son Yik'in Chitam died in combat against the Kayamuca Empire a mere two years after. His defeat was the end of the K'uy hegemony in the east, abandoned to the Kayamuca.

However, conflicts with the Kayamucas did not stop. Yax Nuhn Ahin II (717 - 733), Nuhn Ujol K'inich (733 - 749), and Tz'an Chen (749 - 788) all attempted to regain control of the eastern region and of the Lakamja river, the heart of the Lencas kingdoms. None succeeded. Kan Pet K'awiil (788 - 808) even began to build a fleet capable of contesting the control of the sea, but this led to the defeat of his son Jasaw Chan K'awiil II in 810, the destruction of the Mutulese navy, and the occupation of the eastern coast of the Xuman Peninsula.

This century of permanent conflicts left the Chank'uy greatly diminished in prestige, wealth, and power. They would depend more and more on local hegemons, generally from other K'uy Lineages, for the control of the Eastern Lands and the Northern Peninsula, while they would keep a direct rule on the Western Provinces, the old Chik'in Kingdom, from Uaxakatz'am. The last ruler of the dynasty was Nuhn Ujol K'inich II who died in 895 without an heir, leading directly to the century long succession crisis-turned-civil war known as the Cousins War and the fragmentation of the Mutul.

Culture

Spirituality and religion

The K'uy imported and merged their pantheon to the one of the Chaan Dynasty and of its successors. The main deity was the Mother Goddess, the uniting mother figure of the Dynasty and goddess of the Underworld, darkness, the earth, water, war, and creation. It's from her blood that allowed the first World Tree to grow, bringing maize to mankind once it was opened. It was also her that birthed the first mountain that emerged from the Underworld. However, by the end of the Chank'uy she had already greatly diminished in importance, replaced by other figures, and she completely dissapeared from the religious scene of the Mutul sometime during the Cousins War.

Another K'uy divinity that had a more lasting impact on the Mutul was the Feathered Serpent.

The factionalism of the royal court, its many bloody feuds, and constant plotting of the early K'uy led to young aristocrats retreating to the comfort of artistic endeavors to escape the political spheres. Scholars, poets, painters, sculptors, they formed their own circles, sharing their creations to similar minded friends. Their lifestyle also included hedonistic cults to various local spirits and gods, giving their movement a bad reputation especially among the Tatinak aristocracy.