Restoration War

| Baiqiao Revolution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The siege of Rongshui in 1857 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| F | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 200,000 soldiers | 175,000 soldiers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 90,000 soldiers | 110,000 soldiers | ||||||

| Estimated civilian death: 100,000-150,000 | |||||||

The Baiqiao Revolution (Xiaodongese: 白壳革命; Báiqiào Gémìng, Literary Tuthinan: 慶紅起義, Kyenghwung Kiye "Qinghong's Uprising") was a military conflict from 1856-8 between Xiaodongese nationalists and the Toki dynasty that paid suzerainty to Tuthina which resulted in the unification of the Heavenly Xiaodongese Empire. It also saw the restoration of ethnic Xiaodongese rulers.

The Baiqiao Revolution can be traced back to decades of attempts to overthrow the ethnically Senrian Toki Sougunate which had taken power following the fall of the Jiao dynasty in 1687. The sougunate was increasingly seen as corrupt and unable to modernise and for disrupting Xiaodongese social harmony, moral purity and filial piety. This was heightened as Xiaodongese nationalism became more entrenched amongst the Xiaodongese elite who blamed cultural Senrian influence for holding Xiaodong back from modernisation and for disrupting Xiaodongese social harmony, moral purity and filial piety. In 1856 Ōtsubo Kyira, the appointed daimyō of Baiqiao, began to repress rice riots in the city of Baiqiao leading to the Southern Army led by Yao Qinghong to storm the city of Baiqiao and declare the Heavenly Xiaodongese Empire in the Edict of Sovereignty, with the intention of overthrowing the Toki Sougunate and taking the mandate of heaven with Yao declaring himself as the Xiyong Emperor.

Emboldened by an upsurge in nationalism, Xiaodongese forces were successful in fighting against the Toki and their collaborators, although in turn the Toki were able to mostly hold onto key strongholds. In 1857 the Xiaodongese Southern Fleet succeeded in capturing the city of Rongzhuo which marked a turning point in the war as Sougunate forces were unable to halt Xiaodongese forces. Sougunate forces were further paralysed as pogroms against ethnic Senrians and collaborators became common. In 1858 Sougun Toki Hayato unilaterally promulgated the Edict of Surrender which saw the dismantlement of the Sougunate.

The Baiqiao Revolution is commonly considered to being the birth of modern Xiaodong and continues to shape the nation. After the revolution the Great Cultural Rectification Movement saw Xiaodong modernise economically, entrench semi-constitutional government and lead to a blossoming of Xiaodongese culture. The Baiqiao Revolution also lead to the reinstatement of the Hokka System.

Background

Toki sougunate

In the late-1600's Xiaodong was ruled by the ailing Jiao dynasty, which had been facing internal rebellions, food shortages and widespread plague. In 1680 the dynasty collapsed after its last Emperor Jianying failed to produce an heir, triggering a civil war. A wealthy warlord, Liao Fuxiang, ruled a large dominion in southern Xiaodong and had plans to form a new dynasty. As such, he hired a Senrian rōnin, Toki Sinzō from the Mutumura prefecture to head a personal mercenary force to take over Xiaodong. Toki's family had previously helped Xiaodongese forces in the Soukou War and so was de facto exiled by the Senrian elite. Toki was instrumental in conquering much of Xiaodong on the behalf of Liao, but in 1687 Liao died of liver poisoning. Toki took command of Liao's forces imprisoning the rest of the Liao family before continuing his conquest of Xiaodong. Many former courtiers of the Jiao dynasty was compelled subsequently to pledge fealty to Toki who set up a new capital in Rongzhuo, which he renamed Otomari. Toki declared a sougunate with himself as sougun, declaring nominal suzerainty to the Senrian empire.

Toki's court of nobles soon created a new government with a daijō-kan as the highest organ of state. The Xiaodongese provinces were abolished and replaced with a system of daimyō's - however, these daimyō's were predominantly Xiaodongese feudal lords who had pledged fealty to Xiaodong and subsequently adopted Senrian customs promoted by Toki's court. The new sougunate had a mixed approach to ethnic policy - whilst the daijō-kan was entirely appointed of ethnic Senrians, ethnic Xiaodongese often took up other governmental roles and ruled most of the newly created daimyō although all were expected to adopt Senrian names.

Xiaodongese nationalism

During the decades of Toki rule after initial resistance Xiaodongese scholars had accepted the Sougun's hegemony, seeing the passover of power from the Jiao to the Toki as part of the natural order of harmony, and that resistance to Toki rule would result in social imbalance. As the Sougun began embracing elements of Senrian culture many Xiaodongese scholars accepted these changes as the Xiaodongese elite became more integrated into the Senrian nobility, adopting their customs and language.

In 1758 the Xiaodongese scholar Zhao Zhiguo wrote "The Blossom of Harmony" which attacked Senrian culture as being alien to Xiaodong and having disrupted the social harmony and moral purity of Xiaodongese society. Zhao compared the Toki to leeches, stating that the Toki were slowly destroying the social fabric of Xiaodong, which he predicted would be on a path to social collapse and anarchy if the Toki were not "removed from their positions and sent back to their lands". Zhao also stated that Toki rule had resulted in a "gross perversion" of the Hokka system, with Senrian aristocrats ruling above the natural Xiaodongese rulers. Zhao further advocated for the Toki to be replaced with an absolutist ruler that would restore natural harmony. Zhao's views were considered to be heterodox at the time, and he was executed on the orders of Lord Toki Ōtsubo in 1759 for treason, with The Blossom of Harmony quickly being forgotten. During the 1700's Xiaodongese scholars began to question Toki rule, with the writings of Zhao Zhiguo and the The Blossom of Harmony in particular reassessed as an accurate analysis on the dynamics of Toki rule. It was also during this time period that Neo-Confucianism was formulated by Xiaodongese intellectuals, who believed that traditional Confucianism as practiced by the Jiao dynasty had weakened Xiaodong.

Xiaodongese nationalism slowly developed amongst Xiaodongese scholars and nobles, which was exacerbated as later scholars - most notably Jiang Yunshan in 1841. Jiang was well travelled for his time, having visited Senria as well as western Esquarium, wherein he subsequently declared that Senrian ideals were inferior to Xiaodongese culture, which he attributed to the racial superiority of the Xiaodongese people. In his 1841 publication the Code of Benevolence Jiang accused the Senrians of being naturally barbaric and that Xiaodongese people were blessed with natural traits of filial piety which he claimed led to a harmonious, morally pure society. Jiang like Zhao before him believed in absolutism for the sovereign but also of the absolute moral and political supremacy of the Xiaodongese people over others. Whilst undercurrents of racism had been apparent in earlier Xiaodongese philosophy, Jiang was the first to incorporate it as the core of his teachings. Scholars like Jiang had imported concepts relating to racial hierarchy and eugenics from western Esquarium, and associated such concepts with modernity. Both the "The Blossom of Harmony" and "Code of Benevolence" would have a profound effect on the Xiaodongese intellectual and noble classes who would subsequently embrace the Xiaodongese nationalism endorsed by the philosophers as cynicism towards the Toki elite grew more apparent. Xiaodongese nationalism became defined by its jingoism, racialism and chauvinism as well as its extreme anti-Toki and anti-Senrian sentiment.

The upsurge in Xiaodongese nationalism amongst the nobles and scholar-bureaucrats meant that during the 1800's the scholarly class, landlords and mostly importantly local noble armies became influenced by Xiaodongese nationalist thoughts, believing themselves to be racially and morally superior to the Toki. As Xiaodong's population soared during the 1700 and 1800's the Toki to retain the support of the Xiaodongese nobility kept taxes artificially low, causing a growing financial crisis and more frequent riots and rebellions by peasant classes that in turn undermined the Toki souguns authority as they relied on local noble armies to suppress the revolts.

Toki Reform Movement

Under the rule of Toki Hayato (1833-1858) an ambitious policy of industrialisation was pursued by the Toki government that aimed to dismantle feudalism. Hayato was aware that the turmoil that had gripped his predecessor, Toki Seizi and believed that the Toki government relied to much on the support of Xiaodongese landlords to enforce control over Toki holdings, and during the 1840's came into contact with traders from western Esquarium to learn of western ideas. Toki hoped modernisation on the Toki's terms would quell Xiaodongese nationalism and destory the power of opposing Xiaodongese landlords.

In 1853, Hayato began the Toki Reform Movement (土岐改革; Tǔqí Gǎigé; Toki Kaikaku) which aimed to modernise the Sougunate in technological and administrative terms. The Reform Movement aimed to assert the power of the Toki Daijō-kan over its Xiaodongese counterpart, the Council of Princes and High Officials and to replace the feudal domains with a system of prefectures. The reforms in all were -

- To create a centralised state under the Sougun.

- Creation of national prefectures.

- Dismantlement of feudalism and promotion of capitalism.

- Creation of a modern military and a military-industrial complex.

- Rapid modernisation via commerce and manufacturing.

The proposed reforms by Hayatao were considered radical, with Hayato working with a clique of close supporters to introduce these reforms. The first of these reforms was the development of a modern capitalist economy which Hayato and the reformers believed would cripple the power of the Xiaodongese aristocracy and create a new class of pro-Toki capitalists who would support further reforms.

In 1855, the government passed an edict allowing them to enclose land and have peasants employed by local landlords, which would break peasant ties to the land and thus de facto dismantle feudalism. This measure was heavily opposed by the aristocracy, whilst the central government continued reforms financing the creation of textile mills which intended to start the move to industrialise Xiaodong. This led to a growing disconnect between the aristocracy and the Toki who were increasingly seen as undermining the aristocracy.

Yao dynasty

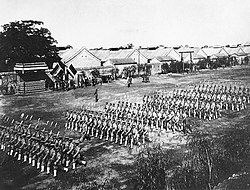

Many of these local armies were undergoing a process of modernisation during the mid 1800's, most notably the Southern Army under the command of Yō clan, who had long been collaborators with the Toki. Under the command of Yō Seiji the Yō's Southern Army was chosen by the Toki to be amongst the first in Xiaodong to modernise in 1847, with Yō creating the Baiqiao Military Academy which his own nephew Yō Fushō (Yao Qinghong) attended and which was under the control of scholar-general Zhang Qiemei a staunch Xiaodongese nationalist. Those within the Southern Army who were trained at the Baiqiao Military Academy were thus more allied to the then-nebulous concepts of a Xiaodongese nation and a Xiaodongese race then any tangible loyalty to the Toki. The Yō clan used its large personal fortunes and connections to Xiaodongese merchants who held regular contact with Aininian and Luziycan traders to import rifles as well as developing cannons.

By the 1850's the Southern Army was recognised as the premier fighting force on the Xiaodongese mainland second only to the Toki's personal regiment that was entirely staffed by Senriana. Nevertheless as the Southern Army became more powerful the Toki souguns relied more on its cooperation in settling revolts and restoring Toki authority - whilst under Yō Seitechi the Southern Army acquiesced, his death in 1853 led to Yō Fushō, his nephew, to take control of the army. Yō appointed his own men such as Jiang Mingguo and Zuo Chaogui - both of which had connections to the Baiqiao Military Academy - to take senior roles within the army whilst increasingly using nationalist rhetoric in its modernisation, with recruits swearing allegiance to Xiaodong before the Sougun. The Southern Army was also split into a land based force and the Southern Naval Forces, under the control of Yao Jingsong.

Famine of 1855

Over the 1850's Xiaodong suffered from consistently suffered from poor harvests - flooding in the south of Xiaodong meant that much of the rice crops for the 1854 and 1855 harvests were destroyed. Bad weather exacerbated the situation, as did centuries old farming techniques that led to low productivity meaning that food prices in the cities increased substantially. The Toki facing massive rice shortages implemented a policy of requisitioning wherein peasants were forced to give the majority of their rice to local authorities to be exported to Otomari to feed the growing industrial population the Toki was cultivating in pursuit of their reforms. Local Toki collaborators and their forces were deployed across the country being set quotas of rice to requisition from local townships, with the quotas often not taking into account the conditions unique to each township. The requisitioning policy galvanised hatred for the Toki rulers amongst the peasant classes, who hoarded large amounts of rice or buried them in defiance of the Toki orders. This widespread resistance to the policy spurred the authorities to raze entire villages in search for hoarded rice with peasants often being executed if they showed defiance towards the policy. The disastrous effects of requisitioning combined with an already poor harvest resulted in over 350,000 peasants to starve the death in what was then the most devastating famine in Xiaodongese history.

The brutality of the requisitioning policy and the accompanying famine led many nobles to question the competency of further Toki rule as resistance to the policy became more widespread. In the port cities of Rongzhuo, Baiqiao, Shenkong, Heping, Hongbu and Renpou riots against the policy were widespread as news of the famine spread across the country. Baiqiao saw some of the worst violence with dock workers deliberately burning ships full of rice bound for Rongzhuo in protest of the requisitioning policy as well as Toki officials often being openly lynched in the streets as ethnic tensions led to further violence. These riots led to the Toki authorities to lead to further crackdowns using local militias.

Opening conflict

Battle of Baiqiao

- Main article: Battle of Baiqiao

The requisitioning policy resulted in widespread unrest in southern Xiaodog as riots against the policy became common in port cities such as leading to more frequent crackdowns. On the 8th February 1856 rioting dock workers in Baiqiao attempted to storm the house of the governor of the city, Chuden Jiro (田中七郎) who requested to Sougun Toki Hayato in Rongzhuo that he use decisive force to repress the riots. Toki agreed, leading to Chuden on the 12th to order his own small army of 2,000 men to put down the riots whilst requesting to the Southern Army for assistance.

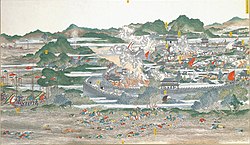

The intense economic crisis, brutal requisitioning policy and fervour of Xiaodongese nationalism led to the Southern Army's leadership to conclude that the Toki had to be removed from Xiaodongese territory. Yao Qinghong and his chief admiral, Jiang Mingguo, travelled to Baiqiao on the 14th with several warships and 10,000 men, ostensibly to aid Chuden's forces - however upon entering the harbour they attacked the city, quickly firing their cannons at the local garrison and deploying the Southern Army into the streets, where they fired upon all Toki collaborators. The battle lasted three days - in the first over 120 of the Toki collaborators were killed, some by the Southern Army and others by the local residents of Baiqiao. The Toki collaborators were not only completely outnumbered by the Southern Army and taken by surprise, but they were also largely armed with swords and old fashioned rifles which paled compared to the more modernised Southern Army.

On the second day the majority of Toki collaborators retreated to the Palace of Heaven, the former residence of the Jiao dynasty and a Taojiao temple, as the Southern Army secured the majority of the city despite the Toki collaborators attempting to retain Xieguo Castle which fell to the southern army. The Southern Army demanded that the Sougunate forces under Chuden surrender, promising them that they would not face retribution. A failed Toki counter offensive later that day led Chuden to commit suicide as his forces surrendered to the Southern Army on the 17th. The Southern Army subsequently entered the Palace of Heaven and gave Chuden's men the option of either being absorbed into the Southern Army or to be executed.

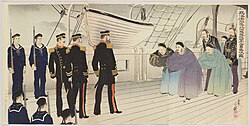

Edict of Sovereignty

With the Palace of Heaven under their control, the Southern Army moved to legitimise their rebellion. After taking control of the Palace of Heaven Qinghong summoned several of his concubines, officers, local landlords and Taojiao priests to the Palace of Heaven where he read the Edict of Sovereignty which stipulated that Xiaodong was no longer under Sougunate rule. This declaration of independence also saw the congregation overwhelming name Qinghong as the divinely appointed Emperor of Xiaodong giving Qinghong the authority to claim the Taojiao's heaven decree and was bestowed the right to reign over the tianxia of Xiaodong as the Xiyong Emperor. In response to the Edict of Sovereignty the Southern Army began to mobilise its forces around its new stronghold in Baiqiao. The Toki government in Rongzhuo rejected the Edict of Sovereignty and called upon the daimyō to aid the Sougunate.

Slaughter of Kuoqing

After taking Baiqiao the Southern Navy under the command of Yao Jingsong advanced onto the neighbouring Kuoqing under the control of daimyō Fukumura Jiichirō. Kuoqing was a symbol of Toki rule in Xiaodong having being built to commemorate the invasion of Xiaodong and had a substantial Senrian population, but like Baiqiao was lightly defended, possessing only a small garrison with little chance of reinforcements. Despite this Yao Jingsong ordered for the bulk of the Southern Navy's fleet to advance on Kuoqing to oversee the wholesale destruction of the Toki elite and subsequently a bastion of the Sougunate's dominance in Xiaodong.

The daimyō, Fukumura, was offered the choice of surrender but refused, spurring the Southern Navy to begin firing upon the city. The small ironclad Xiaodongese fleet quickly destroyed the wooden ships of the local forces whilst their cannons reduced Kuoqing's stone walls to rubble, enabling a force of 8,000 Xiaodongese soldiers to quickly overrun the city. Unlike in Baiqiao where enemy combatants were treated with respect if they surrended, in Kuoqing they were slaughtered on the spot with local residents encouraged to lynch any collaborators. Local Senrian lords were buried alive on the orders of Yao Jingsong, who razed the edifices of Sougunate rule whilst a public "de-Tokification" campaign was launched within the city. Senrian women were raped by the invading forces, whilst children were slaughtered in the streets. Feudal lords who had collaborated with the Kuoqing daimyō were flayed and their bodies hung in the streets of Kuoqing. The harsh measures applied in Kuoqing were censored in territory held by the Southern Army, but served as a powerful tool of psychological warfare amongst Toki elites and the daimyō who supported the Sougunate, with the Southern Army declaring that the treatment of Sougunate collaborators in Kuoqing would be applied to those who resisted Xiaodongese rule.

Middle War

With Baiqiao and Kuoqing under their control, in the spring of 1856 the Southern Army began to advance northwards. The city of Hongbu was given an offer of surrender in April 1856 which they accepted, with the local daimyō terrified of being treated like his counterpart in Kuoqing was. Similar surrenders occurred in Yinbaolei and Zhonghe, enabling the Southern Army to occupy much of south east Xiaodong by the summer of 1856.

Eastern Advance

Battle of Lukeng

The Southern Army faced its first real defeat in September 1856 when it attempted to take the city of Lukeng. Rakuyama Katsumoto, the commander of the Sougunate naval forces to oppose a Xiaodongese takeover of Lukeng. On the 14th September the Southern Fleet met Toki forces at the mouth of Lake Yuezhou which runs through Lukeng, beginning the battle for the city. The larger Sougunate force defeated the Xiaodongese fleet after a week of fighting which resulted in the Xiaodongese fleet to retreat to Kuoqing. However, the success saw the Sougunate fleet decimated despite the Toki's clear naval superiority. The local Xiaodongese sailors on board the Sougunate ships were undisciplined, with rubbish being dumped in gun barrels, weapons sold to local merchants and ships were rarely maintained. The Xiaodongese forces, despite being smaller and less well equipped, were in contrast well disciplined with high morale thanks to a mix of propaganda and a sense of ultranationalism that lent their loyalty to Xiyong Emperor who they had sworn an oath to. Despite the loss, this discipline and loyalty would persist in the Xiaodongese forces to a much greater extent then their Toki counterparts.