House of Commons (Themiclesia)

House of Commons 羣姓之省 gjun-sjêngh-st′ja-srêng′ | |

|---|---|

| Type | |

| Type | |

Term limits | unlimited |

| History | |

| Founded | January 2, 1845 |

| Preceded by | Council of Protonotaries |

| Leadership | |

Speaker | Kaw Rjem MP, Conservative since Mar. 15, 2009 |

Deputy Speaker | Lord P.rjang MP, Liberal since Jan. 4, 2017 |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 339 |

Political groups | Government

Liberals: 181 seats

Opposition Conservatives: 140 seats

Progressives: 9 seats

Independents: 9 seats

|

| Committees | Whole Appropriations Foreign Affairs Defence Industry & Commerce Transport Education Administration Rural Human Rights Minorities |

Length of term | Up to 5 years |

| Elections | |

| first-past-the-post | |

Last election | Dec. 27, 2019 |

Next election | Dec. 27, 2024 latest |

| Redistricting | itself; super-majority required per convention |

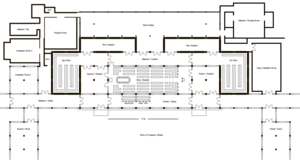

| Meeting place | |

| |

| House of Commons Chamber | |

The House of Commons is the elected chamber of Themiclesia's bicameral legislature, the other being the House of Lords. This house is the one to which the executive branch is responsible and where most government legislation is tabled; in political practice, it is the dominant chamber of the two.

Originally a writing office for drafting decrees and proclamations, historians have emphasized its representative character as the place where those elected by the gentry worked. This character has been exploited by both the crown and court potentates to bolster their political clout. In the Great Settlement of 1801, it was reformed as a representative chamber, with limited legislative powers, to check the crown and its ministers, in conjunction with the Council of Peers. The growing demand for public participation culminated in the Revolution of 1845 that transformed it as the lower chamber of a bicameral legislature.

Name

The House of Commons has several names reflecting the evolution of the organization. In the 15th century, the assembly was called the "lords of the land" (群辟), and in the 17th century it came to be called the House of Notaries (中治書省), as it often met in the buildings that originally royal notaries. The term "house of nobles" (群姓之省) then overtook the former terms in media to emphasize its elective nature. The word "nobles" in this context refers to the major clans that had enjoyed broad political and economic privileges and formed a nobility; the house was named after this class, but subsequently the franchise was expanded first to all who paid a certain amount in tax, and then to all adults.

History

Predecessors

In early Themiclesian politics, it was common for rulers to convoke a formal assembly of nobles to demonstrate his power. From formulaic language, which survives in modern legislation, the assembly usually included patriarchs, barons, and the "lords of the land", i.e. large landowners with recognized governing rights. These assemblies permitted rulers to demonstrate his wealth and the size of his following and to forge political agreements, such as loans or contributions for campaigns. They were irregularly held and not legislative. As far as the assemblies were concerned, there were no internal subdivisions in the fashion of the Anglian Parliament or the Sieuxxerian Estates general.

The first incarnation of the House of Commons is traced by textbooks to 1410, held to rafify the deposition of Emperor ′Ei. The emperor summoned prominent individuals from counties and cities to his increasingly unpopular court, in an effort to purchase support and suppress a firm opposition against him, but the assembly ultimately ratified his deposition, crating the Republic. Throughout the Republic, the general assembly of nobles elected the chief executive and was consulted taxation and war. During this period, the institution was either named by its meeting place, the former seat of the Royal Secretariat, or as "the lords" (群后 / 群辟, n.ghur-gwās / n.ghur-pīk), the term "lords" being a generic appelation for prominent individuals.

The relationship between the general assembly of nobles and the extant Council of Barons remains much-debated today. Some believe the barons acted as an executive or standing committee to the general assembly of nobles, during the period without a monarchy. Unlike in more modern times, barons who did not receive summonses to attend the crown in the Council of Barons were counted amongst the lords of the land and only attended the general assembly.

By the end of the Republic, it is known that elections of some kind occur in some cities that had a number of local lords who were eligible to be represented. While some towns were under the control of a sole lord, others, particularly large ones, were governed by multiple lords. 172 lords held land in or around the largest city, Kien-k'ang, and it is understood that they selected a smaller number amongst themselves to participate in the general assembly.

Ultimately, the general assembly ratified the restoration of monarchy in 1603, in return for the continued recognition for the political rights of the gentry. While all who owned a certain amount of land and participated in local government could be called a lord, barons were lords who had a hereditary and mutualistic relationship with the crown; thus, barons usually supported the crown and represented its policies in conversation with other lords, many of whom had interests against the crown. It should be noted that these councils were (at least technically) consultative, and the crown sometimes ignored them altogether, though invariably at steep political costs. Nevertheless, the general assembly was summoned for the appointment of chief ministers and the establishment of the crown prince.

While the Council of Barons was hand-picked by the crown, the right to participate in the general assembly was more fluid, and the latitude of these promises permitted merchants and early manufacturers to be recognized as part of the local gentry. The general assembly met frequently after the restoration, but absolutism then gained popularity, advocated by the crown's own political faction that drew on royal patronage and bribery. Between 1680 and 1750, the general assembly met only ten times, and the crown's policies often received "broad assent" after the house was packed by the crown's supporters.

The franchise reform of 1630 was considered a pivotal point in the development of the House of Commons. The crown commanded that the gentry of major cities were to raise his taxes amongst themselves, which prompted the aristocrats to sell the local franchise in order to distribute taxation to a broader base. This also meant that the franchise more accurately represented the current distribution of wealth or power, while the franchise had been confined to a single or several families in many towns. While this broadened the ability to participate in politics, it also enabled the crown's faction to develop in more cities and contribute to the 18th century as one of absolutism, pushing the power of the crown to its strongest since the 12th century.

Maverican War

The course of the Maverican Wars had a strong influence on the development of parliamentary democracy in Themiclesia, as the scale of the mobilization and the finances required to suppot policized and unified an audience much larger than any war before. In 1768, the question of Norfeld colonies gained public attention in Themiclesia. The Emperor wished to dedicate all its revenues to the upkeep of the army, while the general assembly tended towards opening the colony to foreign trade and settlement. No consensus was reached, so the Emperor relied on future promises to develop and maintain Themiclesian colonies in the subcontinent. When the Second Maverican War ended, the general assembly refused to fund the refurbishment of the army and navy, and a general sense of anger in the assembly was responsible for the success of the Lord of Gar-lang, who pushed for limits on royal authority in view of recent debacales.

In 1798, Gar-lang assembled the Emperor's barons, disgruntled by the Crown's inability to repay debts, at the Tor Gate and demanded the Emperor summon the the lords of the land to discuss the incredible debt that the nation's incredible debts. The Emperor perceived Gar-lang's demands as a prelude to abdication and so told him that "the time is not yet for that solution." Gar-lang, reportedly, replied that "we are well past that point." Thus on February 15, 1799, the barons and the lords of the land met in the palace and demanded that the Emperor surrender five of his six palaces and half his personal estate in exchange for forgiveness of his debts. The Emperor refused and instead asked for the aristocracy to support the reconquest of Columbia, the spoils and lands wherefrom will satisfy his creditors. His plans were resoundingly rejected by the lords that financed his campaign in Solevant and Camia, who would only support such a plan if defrayed entirely by the imperial estate.

Eventually, the Emperor obtained the lords' consent to retain his lands and three of the palaces, on condition that he divert at least 75% of his income to satisfy creditors and he appoint Gar-lang as prime minister. The lords formed a standing committee to ensure that profits from the royal estate were distributed accordingly. In 1799, the Privy Councillor Lord Mak advised the Emperor that the lords would have no option but to allow him to resume control over the nation's affairs once a new war started, as head of the bureaucracy he would have the option of filling the armies with his allies, who could expand the extend of the war and attempt to recapture lost lands. The prime minister must either then resign or support the war.

Mak's plot nearly fruited at a border skirmish in June 1800, but Gar-lang found out about this plan and confronted the Emperor with it. The lords, returning in October to be outraged by the Emperor's plot, reformed the Council of Barons, requiring at least twenty barons in attendance to ratify the Emperor's orders. Formerly with a quorum of five, the Emperor was able to select his allies to rubber-stamp his orders, but the new limit would require broader knowledge amongst the barons and inevitably involve those who opposed the Emperor. Accusing the Emperor of "betrayal of the people of Themiclesia", the lords gave serious consideration to suspending the monarch or even deposing him in favour of his son, but ultimately decided against it in view of the ambiguous positions of P.ran, the crown prince.

Early 1800s

The post-1804 assembly had both hereditary and elective components and functioned as a legislative body to which the executive was responsible. While some business was transacted by acclamation, counted votes became more common in the 18th century, and as a result the precise number of members also more important.

Through the Council's enhanced powers were primarily designed to check the crown, the spread of democratic political philosophies enticed the mercantile class to support further political reforms that would provide them with political influence. Economic liberalization in the wake of the war also encouraged gentry families to take advantage of their assets and participate in the expanding economy. By 1830, the alliance that instituted the anti-crown reforms had split between hardline conservatives and reformists, the latter of which would join the mercantile lobby and remnants of the Imperialists, who supported a more active monarchy. Merchants and junior administrators staged two important strikes the paralyzed the government in 1841 and 1844. Combined with fear of revolution, the general assembly evolved into the House of Commons.

It has been noted that the House of Commons was not envisoned as the Council of Protonotaries with an enlarged electorate. Themiclesian leaders did not consciously incorporate any significant separation of powers; the Council of Protonotaries and the Council of Peers jointly exercised the sovereign power. Their powers were limited only by the unity and political inclinations of the political class, which comprised of less than 0.1% of the country by population. Criticism for this form of govenrment, however, waxed after the ascension of Emperor K.rjang, who touted the argument that restrictions on royal power established due to his father's incompetence should not apply to himself. K.rjang's machinations, however, did nothing except inspire renewed resistance against royal authority, which many Conservatives believed should be permanently limited.

During the fora between the crown and the two councils, several schemes for the future constitution were tabled. Emperor Ng′jarh sided with the Reformists, hoping that some authority might be restored to the throne through a constitutional monarchy; however, the hardline conservatives were against any "independent power" vested in the crown. The government sent a mission to Anglia and Lerchernt and Sieuxerr to study their respective governments, and the former, characterized by the mission as moderate and anti-revolution, dominated the Reformist cause. Ultimately, their primary demand of a "public franchise" was achieved in exchange for not establishing a written constitution and implicitly acknowledging the sovereighty of the future legislature. The reforms came into effect on Nov. 10, 1844, when the Protonotaries were dissolved for the last time.

19th century

While the House of Commons is so translated in Tyrannian, its Shinasthana name, "House of Many Lineages", reflects its original position as a deliberative assembly of recognized elites, many of whom possessed hereditary titles but were not peers (who sat in the House of Lords). In the first election for the new Commons, held in December 1844, 108 out of 125 members held titles, recognizing their or their relatives' public services. The granting of these titles, though now honourary, still possessed a singificant impact on the democratic process. Amongst candidates of similar views or qualifications, the titled are more likely to be selected and elected. This is particularly true for holders of the highest non-peerage title, the titular lords (倫侯), who could pass down their titles indefinitely.

Early 20th century

Late 20th century

Current composition

Role

Traditions

Meals

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the assemblies that preceded the House of Commons enjoyed the Emperor's hospitality that was calculated at every turn to reflect grandeur and impress attendees. Gradually, a kitchen department arose around the institution of Parliament to provide food for meetings that were increasingly frequent, and food for hundreds of MPs, always prepared at a presentable quality, became a considerable outlay of the emperor's privy purse. In 1808, Parliament voted money to reimburse the Emperor's expenditures on MPs' food. The current kitchen of the House of Commons was built in 1836 and is now overseen by the Clerk of the House. The kitchen provides three meals, tea, alcohol, and snacks throughout the day.

In 1989, it was discovered that the meals served to MPs amounted to 9,500 kCal a day, more than four times the recommended intake of the average adult, and the figure did not include tea or snacks that may be ordered at leisure. However, the study goes on to say that this is assuming that every morsel in the three set meals is consumed, which is rarely the case.

Premises

Inner Court

The Inner Court (上省), or formally the Inner Court of Protonotaries, is the heart of the House of Commons, containing its main chamber, three large committee chambers, common areas, senior administrative offices, and waiting areas for servants. The Inner Court is a walled compound on the inside of the second layer of walls of the Sk'ên'-ljang Palace and west of the Front Hall; it measures around 140 metres on each side, opening into the Commons Corridor, which divides it from the Front Hall. A peristyle is built around the inside of the compound.

The main building (堂, ntang) of the House is centre-north within the Inner Court. First built in the 800s, the current building dates to 1400 and encompasses around 1,970 m², ten bays in width and four in depth. The current meeting chamber is around 14 meters wide and 35 metres long. Benches are laid along the long axis in four rows on each side, accommodating eight MPs per bench. The Speaker's chair is located on the west end, and the addressing podium is opposite on the east. Before the speaker's chair, there is a long table where the officials of the house sit.

East of the far end of the main chamber lies the addressing chamber, which spans the width of the chamber and extends one bay long. Those summoned by the House to deliver reports to the house itself or the Committee of the Whole speak from this position. When Parliament accepted direct petitions from the public, petitions were also read here. Neither measure is common in modern practice, but 19th-century reports were frequently addressed to the House of Commons from members of the House of Lords serving as ministers, who could not speak from within the house. Within the addressing chamber, there are further benches and boxes for the addresser and his assistants or other waiting individuals.

Flanking the main chamber on the south side is the visitors' gallery. A scaffolding for visitors originally existed over the benches, but in 1898 they collapsed, killing four MPs and at five visitors; the remaining stands were subsequently demolished and functionally suppleted with the south corridor. Within the corridor, there are two private boxes, one for royalty and the other for peers. Conventionally, only peers who were government ministers may use this box; other peers sit with ordinary visitors. These boxes accommodate at most a dozen spectators comfortably.

There are two square rooms to the east and west end of the chamber. They were originally the aye and no lobbies, but were later converted into sitting areas for members. The western one is now the Speaker's Chamber, reserved for members, and the eastern is the Visitors' Chamber, available for all of the house's scheduled visitors, which opens directly into the addressing chamber. Members may enter and exit the house through either of these two chambers. Further east and west are the current aye and no lobbies. These two rooms are notoriously stuffy, originally being storage spaces, but they are physically larger than the areas they replaced. There are seats in these rooms for division voting.

To the north of the house is the Members' Gallery, which is normally reserved for members. There is a side door in the chamber that opens into the Members' Gallery. This part of the building opens into the East Chamber, West Chamber, the Grand Gallery, and the two voting lobbies. The East and West chambers are used as seating areas for members.

North of the two chambers sits the Grand Gallery, which is located off the dais that supported the main building. It was built in 1857 out of imported steel girders and glass, spanning the whole width of the main building before it. The Grand Gallery is now used as a corridor and dining area. Breakfast was usually served as a buffet, with serving tables laid out by staff on both ends, while lunch and dinner were served as formal meals; non-members may dine here with an MP's invitation, which by the rules of the house must be kept on record.

The Banquet Room is nestled in the corner created by the Grand Gallery and aye lobby. It measures about 15 m on each side and is the site of formal meals hosted by the Speaker or other officials in the name of the House. Occasionally, large-scale publicity events are also hosted here. Diagonally northwest of that room is the Commons Tower, which (despite its name) is only as tall as the other buildings in the compound, currently laid out as a sitting area. South of the Tower is the Members' Bar, which is another dining area that serves snacks and informal meals. This facility, added in 1908, is open throughout the night and is understood to be especially patronized when sittings run into the evenings. Visitors may snack here with an MPs invitation.

Next to the Bar is Committee Room 2, whose seats are laid out in a horseshoe shape, with the presiding officer sitting on the west side. This building was added in 1876. To its south stands Committee Room 1, which was built in 1344 and originally used as a storage area. It is a square room measuring 14 metres on each side, but as it has a pillar at its centre, somewhat obstructing views, it is not frequently used.

To the east of the Grand Gallery is the Members' Reading Room, which is surrounded by bookcases populated by donated volumes. The Reading Room has two flanking chambers added in the 1890s to function as private studies, which any member may use. South of the Reading Room is the Large Committee Room, which was a wooden building designed only as a temporary home for the House when the main chamber was undergoing renovations. The House chose to retain the building after it realized it needed a new, large committee room. Directly south of that facility is the Visitors' Block, which was the original east wing of the compound. Finished in 1464, this building is still very much a vacant corridor with seats and bookcases, so that visitors may sit here before viewing proceedings.

The Inner Court is rich in political symbols and architectural language. The Speaker of the House sits in the west end, the tradition place of honour in an interior setting. The House of Commons bench sits six to eight MPs under normal circumstances, while each member of the House of Lords has a personal bench; the latter reflects the privilege of peers during royal audiences.

Commons Libraries

Outer Court

Custody house

The House of Commons possesses a custody house (考室) that housed the members, officers, and visitors detained by order of the House. These individuals may be "under custody" of the House or "committed to prison" by the House, the latter phrase used when the individual has been convicted by the House of an offence against itself. The House has historically held individuals under custody for a variety of reasons, including prolonged committee hearings for which the witness will be convenienced by a nearby lodge or for fear of executive interference. During impeachment proceedings, the defendant may also be held under custody to prevent escape or tampering with evidence or witnesses.

The physical building that serves as the custody hosue has varied from time to time and is now Building S4 located in the southwest corner of the Inner Protonotaries Court. This building was formerly accommodation for the Housekeeper and his staff. The custody house has six suites that stand empty most of the time but may be used as dormitories if accommodation elsewhere is not available. Each suite consists of a bedroom, en suite, and sitting room, the last opening into the corridor. Until 1988, prisoners ate from the same kitchen that produced MPs' meals, the Gentleman-Captain causing the food to be delivered; since MPs abolished their dining service for austerity, food is brought from the Cabinet Office kitchen instead.

The custody-house is not considered a prison under the Prisons Act that regulate most of the country's correctional facilities. For this reason, inmates here do not have certain rights that ordinary prisoners do, such as correspondence and visitation with family or legal counsel, access to open space, or medical attention. However, the Gentleman-Captain, has discretion to allow any of these benefits. Historically, only the prisoners deemed honourable—either an MP, a titled person, or official of the House—were allowed to walk in the House's grounds, without an accompanying official.

A. R. Johnson, a foreign correspondent working in the Themiclesian Parliament, once commented "the custody house is a black site of a kind. You have no right to communication, counsel, or even fresh air, you are not entitled to be informed of charges against you or to an open trial where you may contest them, and the House of Commons can arbitrarily extend your imprisonment, technically forever. That is implausible but legally possible. The Themiclesian government does not acknowledge your detention because the custody house does not belong to it."