Rang Dara

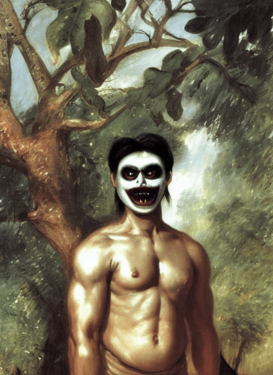

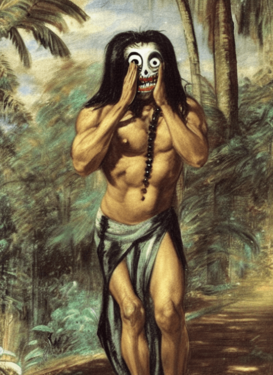

Rang Dara is a vengeful spirit in the folklore of Hindia Belanda. He is the malevolent spirit of a commoner man who was sentenced to death for courting an Anjanian noblewoman during the Anjani Empire. Resembling a muscular human male with a grotesquely deformed white face and hollowed eyes, the Rang Dara is a creature that, according to legend, can be found on certain nights in the jungles of Anjani island. He wears a traditional sarong skirt and a necklace made with dried flowers. When he appears, he remains eerily still and quiet until he attracts the attention of an unsuspecting victim and elicits fear, at which moment he lunges towards them whilst screaming a ghastly screech and cackling hysterically. He preys on lost travelers, killing them by clawing out their hearts. It is said that the best method to prevent being attacked by this creature is to avoid looking at him directly, pretending he is not there, and not being afraid of him.

Some versions of the legend state that the Rang Dara may sometimes disguise himself with the face of an attractive man. One could supposedly tell if a male-seeming person was really the Rang Dara in disguise by asking him to blow out a candle, as the Rang Dara cannot blow out a flame. Still another version of the legend states that the Rang Dara would flee if one were to utter the name of Hantu Pemandu, a benevolent ghost who guides lost people to safety and guards them from dangerous beings. The Rang Dara is said to be so dreadfully powerful that the people of Anjani island in the colonial era warned against uttering the name out loud and would not speak it even in the safety of their own homes.

Legend of Rang Dara and Melati

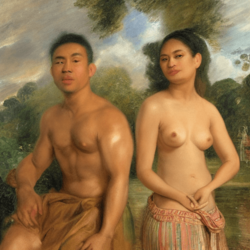

According to legend, Rang Dara was a bricklayer who fell in love with an Anakdatin named Melati, the daughter of Dato Setiaharta, supposedly an Anjanian lord. Rang Dara courted Melati secretly, but he learned that she was engaged to be married to the son of another Anjanian lord. The couple vowed to marry no matter what, eventually revealing his courtship to her father. Angered by the young couple's defiance, the lord sent his daughter away to a nearby island, where she was put under the watch of a relative until the time for her marriage with her betrothed. Rang Dara rowed to the island despite the risk to himself, broke into the residential complex where she was being held, and freed her. The couple ran away together, jumping from the island in a small outrigger and sailing for a short time before arriving to a secluded lagoon at the base of Mount Kaserahan. They settled into a small hut in the hills of Kuala Tinggi; this was Rang Dara's childhood home and where his father had practiced bricklayering before him.

It is said that the couple lived happily for a while before Melati fell ill from a disease. Knowing he had neither the skill nor the wherewithal to treat her properly, Rang Dara arranged for her to be transported back to her hometown. Upon arriving at Dato Setiaharta's kraton (palace), Rang Dara was seized by palace guards and thrown into prison at the command of Melati's father. Melati pleaded her father not to harm Rang Dara, a wish that her father granted. He promised not to harm Rang Dara only as long as Melati was in residence. Melati recovered from her illness after receiving treatment for several months, but she was unable to live without Rang Dara. She slipped out of the palace late at night to see him in prison. At the prison, Melati and Rang Dara rekindled their love, but Melati's father heard of their reunion and had them both brought before him. The story took on a tragic turn when Melati's father, Dato Setiaharta, announced that Rang Dara was to be executed, as the love between a common bricklayer and a noblewoman was a disgrace to Melati's family. The next day, as punishment for his 'transgressions', Rang Dara met his fate; his face was flayed alive, his body disposed of in a nearby jungle.

Melati was devastated by Rang Dara's death and blamed herself for his death. She committed suicide by drowning herself in the palace pond. Her suicide is thought to be the origin of yet another ghost in Hindia Belandan folklore, the Hantu Anakdatin, who is said to haunt ponds.

Ahistorical method of capital punishment

This method of punishment has no historical basis in Anjanian history, as Imperial Hyangism, the state religion of the Anjani Empire, forbade the killing of criminals by 'disfigurement, decapitation, dismemberment, or immolation'. Furthermore, capital punishment was considered a privilege of the Anjani Emperor and was only employed for the "most horrific acts," such as treason and murder, by the Emperor. Imperial capital punishment involved the drinking of a potent poison but not at a dose strong enough to kill the condemned, only to paralyse the muscles and render the criminal unconscious. Whilst unconscious, the criminal is stabbed with a kris through the heart. The punishment for murder meted out by the Emperor's vassals were significantly milder than the punishment for murder in territories of Imperial immediacy, as the punishment for death was usually exile or life-long servitude as a Frontier's Guard.

Evolution

The earliest account of the legend is from the 9th-century Annals of Otherworldly Beings, which is an account of Anjanian mythological stories authored by Hang Kalaika, a prolific court historian of the Anjani Empire. In the 13th-century, it was mentioned in an anonymous apologetical work of Esoteric Shi'ism, On the Boundaries of the Profane and the Sacred ('Ala'l-Hududa'l-Dans wa'l-Muqqaddas), which constituted one of the earliest Esoteric Shia attempts at ridding superstitious beliefs in the regions where the faith had begun to take a foothold. The tale was again mentioned in a similar apologetical work of the 18th-century, this time by a Javanese Lutheran missionary, Romo Kalis, who quoted the story from the Esoteric Shia account and with which he agreed on the harm that superstition had to society.

During the colonial era, the tale of Rang Dara permeated the common consciousness of the Hindia Belandans, particularly with the growth of literature and drama using mythological Anjanian imagery in the later half of the nineteenth century.

In popular culture

The Rang Dara has featured in numerous artistic works, including paintings, music, theatre, literature and cinema.

Colonial theatre and early cinema

The story of Rang Dara was first dramatised into a play in 1789, titled Penghoeni Belantara (The Jungle Dweller), which was positively received by the colonial audience. It was adapted for film in the silent era, producing three separate works between 1913 and 1918. The most popular of the silent adaptations was directed by Njoe Sekar in 1918, earning him substantial critical recognition and a star of the Order of the East from then-Governor-General J.P van Limburg-Stirum.

Literature

The story of Rang Dara had a great effect on colonial Hindia Belandan literature, as evidenced by allusions in the works of Theodoor de Amboyna, Antoon van der Meer, and Mochammad Djajakoesoemah, as well as current Hindia Belandan authors such as Elna Natalie and Damar Amatsenang. The tale is also alluded to by the Hindia Belandan sociologist Mardjono van Dries in his seminal book Keatas, Kebawah (upwards, downwards) which provides a commentary on social class and habitus.

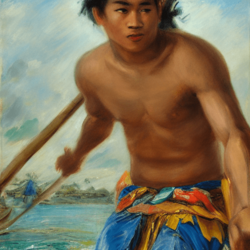

Paintings

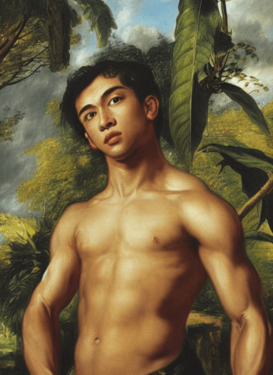

Numerous paintings have been produced of Rang Dara, both portraying him and Melati happily in life, and as the malevolent spirit that he became after death. The iconic Rang Dara In His Kingdom, a painting by Eduard de Eerens, currently hangs in Noordwijk Gallery in Jakarta, and was seen by the poet Diana Kamaloeddin, who was inspired to write her famous poem Look Not Upon My Mangled Face, My Love. The century-old painting has been exhibited in numerous galleries and museums, but remains best known for a series of urban legends about what has happened to those who have seen it in person. Owing to the tragic tale of Rang Dara and Melati, one urban legend holds that couples who visit Noordwijk Gallery should not look at the painting for more than a few seconds, lest they break up within the year.

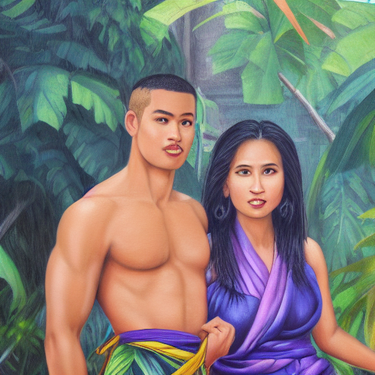

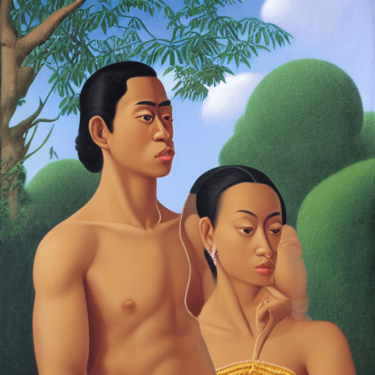

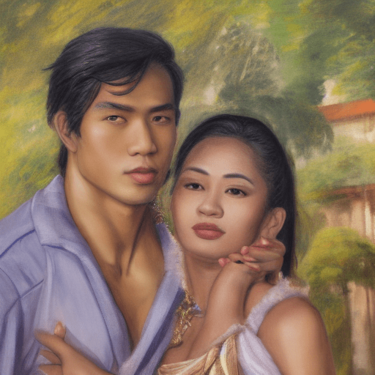

Rang Dara dan Melati, by Boerhan, 1978

Rang Dara dan Melati di Taman, by Niken Soekarja, 1968

Pasangan Dalam Hidup dan Mati, by Koentjara, 1963

The Attack of Rang Dara, by Sylvia Amatkarim, 1989

Contemporary cinema

In contemporary cinema, the tale of Rang Dara spawned an entire subgenre of jungle horror films, the most successful of which was Hijau Kelam (1987), which had a limited international release in select Astyrian countries. Djoewana Setia's award-winning film Sang Rang Dara (2006) became a cult-classic by exploring Rang Dara's inner life and attempting to humanise his character. The trend of humanising Rang Dara continued with Melati Jangan Pergi (2009), and the TV series Rang Dara dan Melati (2018), which centred around the tragic love story of Rang Dara and Melati, without incorporating the mythological elements of the traditional tale.

Music

A song by the Hindia Belandan indie pop group Vendredi sur Terre titled The Emperor referenced the Rang Dara.