Urban planning in Dezevau

Urban planning in Dezevau is the planning and design of cities in Dezevau. It has a history that stretches back two thousand years or more, though modern urban planning only emerged after Dezevauni independence in 1941. It is a key academic, governmental and political concern, influenced strongly in the present day by the nature of local and federal power, and by the ideal of a democratic and socialist economy; its importance relates to the high level of urbanisation in Dezevau, which is about 70%. The most significant urban planning agencies are the district planning commissions, but like many other political processes in Dezevau, consultation with and input from both higher and lower governmental strata are crucial.

History

Medieval city-states

The concept of the city (Ziba: Ju; CT: ju) had great cultural and political significance in premodern Dezevau. In some sense, the city's magnificence and history legitimised the city-state's position among other states (Ziba: Boga; CT: boga) in the region; settlements which were not the capitals of city-states or a province of the Aguda Empire are generally not referred to as cities in premodern Dezevauni history. As nexuses and seats of power, there was significant attention paid to ensuring cities were defensible, functional and beautiful. The city-state's ruling council or monarch generally had significant involvement in the city's design, layout and construction.

Perhaps the defining feature of the medieval Dezevauni city was the city wall. It was not only the most important line of defence, but was also the most symbolic delineator of the city, in contrast to its hinterland. It generally surrounded the city on all sides, including on sides facing water, as much if not most warfare was naval. The placement of the gates in the wall oriented the city's psychological sense of place and direction, and in some cases, gates had strictly prescribed uses; commonly, there was a single main gate for the waterfront (almost all cities had a marine or riverine port). Despite the importance of the wall, however, there were usually some areas just outside of the walls which were urban in character, though they were sometimes only temporary in nature. These included military camps, quarantine facilities, markets (sometimes set up to avoid regulations which only applied within the walls), port facilities, tanneries, slaughterhouses, or simply overflow urbanisation from an overcrowded city. When extending city walls, the city government was able to sell the newly enclosed land to generate funds, but it was also an important way for the government to shape the city's development and leave its mark on it for posterity.

The space within the city itself was generally densely built up and populated, with little or no greenspace. There were generally identifiable districts, which governments encouraged the development of at times, for utilitarian purposes. For example, markets tended to be located near the port and/or gates. Near the centre of the city was generally an open area, the civic ground, around which the city's most important civic institutions were located. Though normally just the most important thoroughfare, it was used for meetings, demonstrations and ceremonies; popular involvement in government was largely through this venue. The most powerful people in the city often lived in residences just behind the buildings surrounding the civic square, though in the later medieval period, and in cities where inequality was greater and civic politics weaker, there was a tendency to move to the edges of the city. There, land was more available and more defensible, and more private and luxurious residences could be constructed.

Land was owned by individuals, but private alienation of it was not always possible where restricted by custom or law. There was no concept of artificial personhood as with corporations, but some property was seen as belonging properly to institutions, on whose behalf individuals administered it. On death, the deceased's real property was generally not distributed by will, but by the appointment of a ngamuigounau, who would distribute it among the deceased's friends, supporters and relatives, considering their closeness, need and other social factors. The ngamuigounau had discretion in these duties, but legal proceedings could be brought against them if the discretion were exercised too capriciously. In this way, significant holdings did not concentrate in private hands over time, though renting and landlordism were by no means uncommon.

Some buildings or land became associated with families or institutions over generations, and acquired special significance or status in that way. Most property could be dealt with privately in the ordinary way by individuals, however. Governments sometimes compulsorily acquired private property for public purposes (such as when it was necessary to widen a congested road, or to strengthen the city walls), especially when it was seen as being improperly used or unused; compensation, if provided, might be negotiated in the form of land elsewhere, certain rights, or money. It was furthermore an everyday function of government was to prevent private protrusions onto public spaces such as roads. City buildings were generally built of stone, and thus fairly long-lived; this also played a role in fire prevention.

Urban civil infrastructure was a key concern of city governments, and included the paving and cleaning of roads, the maintenance of canals and port facilities, the provision of clean water, and dealing with traffic congestion. Water (apart from collected rainwater) was usually sourced from a nearby river, and was sometimes pumped or piped to fountains or canals in the city to make it more accessible. The management of the water supply was closely tied to drainage and sewage systems, which consisted of stone or brick-lined trenches (or sometimes pipes) which discharged outside the city, often downstream at a river. This system was comparatively advanced in the world for its time; ample combined sewers and drains both mitigated flooding and aided in sanitation, especially where running water kept them clean. Waste from households, business and from off the roads was often disposed off by sweeping into the drainage channels, even though this was often discouraged or prohibited as a nuisance which could contribute to blockages.

Aguda Empire

The Aguda Empire generally saw the continuation of medieval urban trends, albeit in a context of accelerated population growth, commercial activity and urbanisation. The capital, Dabadonga, was exemplary of this, and had a significant impact on later urban planning. Significant alterations to the typical layout of the city occurred in connection to the demands of imperial administration and defence, however. In the core regions of the empire, furthermore, the importance of the walls decreased, as they saw little use given political stability and the security of imperial hegemony.

The relationship between the empire and its subjects was reflected in the trend of the construction of citadels, which provided an extra level of defence for and control over the city. They were areas of the city which were separate to and more fortified than the rest of the city, usually built at the edge of the existing walls where there was open space. They projected military power whether the threat was attack or revolt, and were also secure areas which isolated administrators from the rest of the city in a cultural and social sense. Citadels were not built in all cities, however; they were more common near the frontiers, where threats of either or both revolt and attack were more present.

In some regions, depending on local conditions, only provincial capitals had the privilege of maintaining city walls; other settlements, though they might have a citadel, were deprived of the security and status of a wholly walled city. In some cases, existing settlements' walls were razed, sometimes as a response to some provocation such as a rebellion, but also as part of routine governance at other times. Another way in which the Aguda Empire hamstrung unwanted urban development was by having the civic ground (if one existed) built over, depriving the populace of its traditional avenue of expression. This was rare, and usually a punishment; it seems to have been effective where implemented, though the success of the measure may also have been to do with other policies implemented simultaneously.

A trend related to citadel-building was the retreat of the ruling classes from public life, or the retreat of governance from public engagement. Where they did not live in the citadel, many of the richest and most powerful people, families and institutions came to occupy areas near the edge of the city, which were more isolated and defensible from the rest of the city, as citadels were. Some even came to live beyond the cities, in the countryside, as urban unrest became more of a threat than foreign attack; this was comparatively rare, as rural unrest was also a serious cause for concern, perhaps one even more difficult to deal with than urban. Further from the centre of the city, it was also less crowded and more comfortable; much of the grandest and most luxurious Aguda architecture that survives was a result of this trend. Overall, urban configurations reflected cities which were increasingly ruled by an empire-wide class, rather than which were polities in their own right.

Dabadonga was the zenith of Aguda Empire urban planning, being its planned capital, and for a time, its biggest city. Its regular and spacious layout benefitted organisation and logistics, and also encouraged grand architecture. It had the most advanced system of water supply and drainage of any city in the empire, as well as the most advanced canal system. Uniquely (when it was constructed), it had important internal walls, which were a kind of extension of the logic of city walls in other cities. The central walled governmental district reflected where power lay. Dabadonga influenced other cities in the empire, and other successive cities.

The dying days of the Aguda Empire saw deurbanisation and a decline in its governmental capacity. Despite this, its city governments largely continued to function until they were taken over by a greatly pared-down colonial government, which largely left the old cities alone outside of strategic areas such as ports, government buildings and fortifications. In a few cases, Aguda urbanism survived as influences in the present day, in Dezevau, Penduk and Surubon.

Colonialism

Though they retained formal importance, provincial capital cities were neglected in terms of governance by Saint Bermude's Company. Attention was paid mainly to securing key facilities and areas, such as fortifications, ports, administrative offices, canals and such. The Aguda Empire's political and economic decline saw urban governance become unable to carry out basic functions such as the maintenance of roads, while the cities themselves experienced deurbanisation. The artisanal classes and service workers who congregated in cities reoriented to serve the new Euclean or Euclean-affiliated ruling class, but overall experienced a decline in size and complexity as Euclea became the centre of global trade and manufacturing. Large areas of cities became picturesque ruins, occupied only where they were proximate to colonial activity, largely only by the lumpenproletariat unable to assimilate into the agricultural economy. Their occupation by bazaars, beggars, brothels, and generally non-capital intensive service industries, has been analogised to the situation in the developing world in dependency theory.

Bouches-de-Jouvence (present-day Naimhejia), Saint-Bermude (today a part of New Begia), Mount Palmerston, Crescent Island City and (to a lesser extent) Dhijivodhi were the main cities in Dezevau which were built up and governed in detail by Euclean administration until the 20th century. Centres of colonial governance, entrepots, and even residences or workshops for the Euclean regime, they were an exception to the decline of Dezevauni urbanism. There, urban planning was largely imported from the metropoles of the colonial rulers (Gaullica, except for Estmerish Mount Palmerston). As monuments, exemplars and models of Euclean urbanism, they were influential on later Dezevauni urban planning.

With the nationalisation of Saint Bermude's Company by the Gaullican government, change was slow, but the advent of the National Functionalist regime saw change accelerate. It is controversial what their intentions with regards to colonial policy were, but there are signs that it considered a significant change in the existing policy towards the industrialisation and governance of colonies. In any case, its plans largely went unrealised or were not detailed, owing to internal bureaucratic resistance and confusion, and then its defeat in the Great War.

Early independence, industrialisation and modernisation

In the wake of the Gaullican defeat, and the turbulence around the different groups trying to take power in the Estmerish mandate, not much attention was paid to urban planning. Some recently displaced peasants were able to return to their villages from the cities, but cities generally grew in size with population growth and the arrival of ethnic and political refugees from outside the proposed borders of Dezevau. Informal settlements sprung up haphazardly where there were jobs, such as near industry or port facilities. These were also the locations most crucial to those seeking to take power in Dezevau, and so they were often administered along military lines, with makeshift fortifications defining some cities for a time. Some deurbanisation occurred where industrial developments built by Gaullica were destroyed, abandoned, or dismantled and shipped away by Estmere.

The founding of the socialist republic in 1941 established a modicum of order, and most cities were organised as municipalities or as a small number of closely related municipalities. Mostly, the attentions of the new regime were on the agricultural countryside, but cities were natural hosts to nascent industrial development, especially as they continued to play hosts to unemployed, displaced populations. Industry was focused on domestic consumption and development, and so was dispersed across cities across the country, as so to service local areas. Universities were also established in cities in a similarly dispersed way.

Federal and state governance focused mainly on cities for their industry and role as centres of education, largely leaving other matters to local self-governance. For about a decade up until around 1955, local democracy flourished. Municipal politics became an incubator for popular understanding of and participation in council democracy. The importance of industry and universities in cities meant that unions and students were particularly significant participants in urban politics. Policies that emerged in this period include the formalisation of informal settlements, being not only popular at the grassroots level, but the most realistic option for cities with limited funds and administrative capacity. Running water and sanitation were another key and popular priority for cities, but progress was slow in other areas except where it was able to piggyback off industrial development (e.g. for electricity, paved roads, mechanised firefighting). While primary education was not a municipal responsibility, generally speaking, less formal schools run at the municipal level contributed significantly to its accessibility during the period when its implementation was still patchy.

Rise of urban planning paradigm

From the 1950s onwards, as the political, diplomatic and sectarian situations stabilised, much greater political emphasis came to be placed on industrialisation, modernisation and planning, with concomitant centralisation. The maturation of urban planning as a discipline internationally greatly influenced higher-level governments in Dezevau, which came to see it as an important tool for the development. Along with the mechanisation of agriculture (reducing labour needs) and population growth, industrialisation drove urbanisation at an accelerating rate. Land disputes between periurban villages and urban immigrants intensified in tenor, as did social conflict between established urbanites and new immigrants (primarily Juni and Geguoni). Such problems were the juncture at which higher level governments began to assume stricter control of the cities. At the same time, this drove conflict between the representatives of local urban democracy and those more concerned with overall development, or the needs of would-be immigrants and the countryside.

Municipal powers were increasingly overridden and assumed by planners, many of them university-educated, and many overseas at that. State economic commissions (and subsequently various federal commissions) became the main governing entities for urban development, controlling things such as the construction of housing, electrification, sewage processing, the placement of factories and transit systems. They tended to bring modernist ideologies to their work, planning to mathematically optimise productivity and efficiency in all things, and being quick to discard the old (though it is argued that they inherited a sense of the city as essentially politically and economically central). This approach saw the loss of certain historic buildings and areas which were subsequently mourned by the preservation movement. It also drove grassroots opposition, which chafed against bureaucratisation, micromanagement and alienation. This was especially the case with regards to more radical proposals, such as some disurbanist concepts which were never put into practice; the relative political difficulty of displacing villages continued to keep urban footprints small. Fierce local opposition, however, was often politically naive, and local democrats often politicised rapidly or were easily swept aside by centralisers, at least at law. However, planning commissions continued to consult locally where convenient and applicable, such as for traffic management, and also maintained numerous existing practices such as neighbourhood formalisation (as part of the policy disputes known as the "Housing Wars"); there was never a complete rupture in the urban governance system.

In part because of conflicts with existing power structures and populations, as well as because of the demands of industrialisation, numerous new settlements were established in this period in remote areas. Tightly planned modernist towns were built around factories, mines or other key economic locations, especially in the Stirani Highlands where areas were opened to deep mining or agriculture via irrigation. Many of these settlements did not work out, either for practical reasons or because their political backing evaporated, but those which remain are unique exemplars of historic urban planning today.

On the whole, the 1960s-70s saw rapid economic growth and complexification of urban governance structures, helping to burgeon a managerial class in the process. Many institutions of urban life date from this period, including the gogou. Various contemporary assessments of the period differ in their emphasis on the curtailment of democracy and mismanagement, as opposed to the necessity of central management during a period of complex development. In any case, grassroots urban grievances would subsequently find expression in the upheavals of the Cultural Revolution and in the Localist movement.

Bazadavo

It was decided shortly after independence that the capital should be a new, planned, centrally-located city. However, with political and economic pressures, little was done on this front while Dhijivodhi was maintained as the temporary seat of government for a number of years. The city began to be planned and built in earnest in the 1950s, however, seeing input from a variety of political and planning ideologies, and the experience of planning the new city in turn influenced other cities across the country. Because of its origins, Bazadavo is unique among large cities in Dezevau for its highly regular layout, wide open spaces and entirely modern core. However, reactions against modernist urban planning have seen the edges of many of these innovations softened over the years, especially as Bazadavo grew beyond being merely the seat of government institutions into a major city in its own right.

Localism and the Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution of 1980 kicked off a period of intense scrutiny on the Dezevauni Section of the Workers' International and centralised state organs in general, including the state economic planning commissions and federal planning entities. Progressive and radical movements and proposals gained currency rapidly, spreading through the direct democratic neighbourhood councils, municipal council meetings, universities and demonstrations. This affected urban planners as well, who found their backers in the central government suddenly reticent or unable to act. Urban planning largely responded to the Cultural Revolution positively, with the younger generation of planners stepping up to lead the implementation of more consultative, locally-oriented policies and processes; an older generation of urban planners, however, were displaced to some extent, leading to what some considered a loss in inherited technical knowledge. A greater sense of pluralism was also established; the idea of a single public interest was dismantled into seeing urban planning as a more explicitly contestative, political process. Political changes resulting from neighbourhood and municipal assertions of power saw the main institutions of urban planning become the district planning commissions (at a city scale), as opposed to higher-level bodies; this was one of the most significant formal changes from the Cultural Revolution era.

However, beyond the comparatively uncontroversial democratisation of institutions, the Cultural Revolution was also the birth of the Localist movement, which might be considered anti-urban planning altogether. Localism brought together heterogeneous movements and impulses, often previously apolitical or politically naive, whose main cause is greater local power. While they are not opposed to community organisation, Localists oppose all that the higher-level planners represented, from economic plans to uniform regulations to immigratory neighbourhood densification. Permeating politicisation has long been a feature of Dezevauni public institutions, but the rise of the Localists escalated the level of conflict present in urban planning contexts. At the same time, the Localist movement is substantially heterogeneous and situational, and as such, constructive efforts to reconcile Localism and urban planning have yielded fruit at various levels of governance; a particularly significant aspect is understandings around the duties local governments take on when they assume more power, in the wider contexts of the city, region and country.

Information Revolution

The Dezevauni approach to urban planning could be identified as linked to and integrated with internationally recognised approaches such as participatory planning and communicative planning by turn of the millennium. Significant new changes were thus possible as the flow of information was heightened and changed by the Information Revolution, involving greater and faster input from the public, as well as much more data input and processing from other sources. A soft rebound from Localism was also seen, as a grassroots internationalism emerged with links to Internet youth culture. It may be noted that to an extent, the Internet leapfrogged other telecommunications technology in Dezevau, things like landlines having never become widespread.

While face-to-face meetings are still the primary method for participation, decisionmaking and community-building, a great deal of information can now be transmitted and received online. On one level, it can be a logistical support for meetings; complex or lengthy information can be sent before or during a meeting, reducing the need for physical transport of paper, and votes can also be taken more quickly using electronic devices. On another level, however, there is the potential for transformative changes. For instance, in some cases, consultation has been limited to online information and polling, with comparatively little discussion in person; this trend emerged as a result of authorities cutting corners with regards to the normal process, but it has since become recognised as a potentially independent way of doing things, with fiercely debated positives and negatives. The Internet has also become an alternative public forum; where in the past, neighbourhoods tended to achieve consensus easily or have only a few main material interest groups represented, national or international theoretical debates now play out more often at the local level. Few see greater connectivity as an unmitigated negative, but there are considerable practical and theoretical conflicts, including at a generational level (though such is already decreasing with the natural progression of time).

Less controversially, much greater processing power has also allowed for planning in much greater detail, at greater speed, and with better technical specifications. Dezevauni urban planners have widely adopted geographic information systems and other computerised, Internet-linked tools. Modelling is another important aspect, widely adopted and practiced; it has humorously been referred to as a sacrament in Dezevauni urban planning culture. Some have warned of a new iteration of the state economic planning era, in terms of technically adept but out of touch planners gaining too much power, as far as many opaque algorithms have gained political credence; this has been tied to broader debates in democratic backsliding.

Governmental and consultative framework

Urban planning in Dezevau is a process carried out by a variety of institutions with differing roles to play. Efforts are made to seek input from all relevant stakeholders, such that consultation is extensive compared to the processes adopted in other systems around the world. The primary urban planning bodies are the district planning commissions, but they are significantly beholden both to certain state and federal bodies and to municipalities, in specified subject areas such as intercity transport, industrial land use, eviction, and so forth.

Districts

Districts (Ziba: Vonibadhe; CT: vonibadhe, also translated as federations) are administrative units of varying size, generally formed by the voluntary confederation of municipalities, though certain higher level governments have indirect powers to induce or prevent such. Districts are approximately contemporaneous with cities' metropolitan areas, though being the result of legally voluntary association, boundaries can be inconsistent; district populations range between from the tens of thousands to Bagabiada at 6.8 million. Special quasi-districtal structures exist for interstate cities, though districts can also technically cross state lines. Most municipalities are part of districts, but those which are not retain most of the powers normally held at district level. Considerable power is held at the district level, including most of the responsibilities that fall under urban planning, such as arterial roads, commuter transit and public plumbing; being able to arrange for and secure these services is the main reason for associating to a district. District councils (districts' top-level governmental body) are filled by the delegates of municipalities.

Districts can also be associated with each other in larger groupings called regions. Districts can be associated with several or no regions. Such associations have replaced many of the functions association with the old states; regions are focused around working out solutions to issues which may affect a few districts, such as water distribution or regional rail. Governance regions should not be confused with other usages of the term region, as a purely informal or strictly technical-geographical term.

District planning commissions

District planning commissions are the bodies with primary responsibility for most aspects of urban planning. Appointed by district councils, they are executive agencies mainly staffed by professionally trained urban planners, designers, architects, etc. Though district councils have oversight and are the formal delegators of power, district planning commissions have the legal power to carry out their plans otherwise. District planning commissions do not themselves operate most systems of the city, but rather have a privileged position among the other district agencies (such as those managing water, sewage, parks, drainage, roads, etc.) They are usually the coordinators of construction at the district level where resources are needed from higher levels of government. The head of a district planning commission is known informally as the chief planner.

While district planning commissions are the vehicles for urban planning in urban districts, many non-urban districts have them as well in a similar capacity—their role is often similar in terms of managing land use and spatial organisation, though their daily concerns are quite different than in urban contexts.

State and federal commissions liaison

District-level planning is significantly imposed on by federal and state policy, mainly in spheres where governance at a greater scale is deemed appropriate. Relevant areas are dealt with through liaison staff (on both ends) between the district planning commission and the relevant state or federal agency. This structure creates a degree of "vertical" continuity for particular policy areas (as opposed to "horizontal" integration between different levels of government, such as the federal or municipal); the internal structure of district planning commissions may also reflect the different areas. Such a structure has been assessed both positively and negatively, as maintaining continuity and institutional robustness by cross-bracing against friction between different levels of government, or as unnecessary duplication and complexity in government. Efforts to reduce federal-state conflict can benefit districtal governance by reducing the number of duplicative liaisons.

Relevant areas of federal or state power include non-strategic industries (e.g. logging, light manufacturing, civil construction), regional roads, healthcare and the labour market. Water (as in rivers, canals, dams) was traditionally a state responsibility, but as a result of interstate disputes and a growing recognition of a global water cycle, has increasingly become a federal responsibility. Electricity has also increasingly become a federal responsibility as integration and economies of scale have intensified. Relevant areas of federal power include defence, telecommunications and international transportation. Generally, state agencies have more impact on urban planning than federal. Not all agencies have liaisons, while some districts may vary in terms of what they liaison about; for example, crematoria, though typically a state responsibility, might require very little attention in a small and youthful district.

Historically, state and federal government were more able to dictate to district governments, doing so mostly through the state economic commissions, which were preeminently agencies for industrialising, imports and exports, and maintaining agricultural and other extractive activities. However, districts gained greater power after the Cultural Revolution, and a more continuous, decentralised, consensus-based model was adopted even in key areas of economic management.

Though not an executive commission in the same way, interactions between the judiciary and district planning commissions largely follow the same model.

Municipal government and liaison

Municipalities (Ziba: Zangenedhai; CT: zangenedhai, also translated as communes) are the lowest independent level of government, with their creation and subsistence being constitutionally protected where they are voted upon by their residents; decisionmaking is substantially direct-democratic in municipalities. In an urban context, municipalities are roughly equivalent to a neighbourhood or suburb. Municipal meetings are held every week, with it being common under normal circumstances for the municipal business to be delegated to the weekly building or sub-municipal neighbourhood meeting; at such meetings, every resident has a vote on business matters, so that vote counts must be reported back to the municipality. Municipalities can delegate to sub-municipal neighbourhoods (Ziba: Mhobi; CT: mhobi), generally doing so only in large municipalities for minor matters like garden plot allocation or litter.

Municipalities generally confederate to form districts, as aforementioned. Many municipal powers are thus exercised by district government, but municipalities retain significant power locally, and are also important for their ability to affiliate to or disaffiliate from districts, and their legal ability to subsist or come into existence without the approval of higher administration.

District-level planning must take into account retained municipal powers, over such matters as the allocation of housing, buildings' rights of way, childcare and noise limits. Ceded powers usually include local roads, public transport, firefighting, parks and shops. However, in practice, districts consult municipalities even where not strictly necessary, while municipalities see the necessity of district-level governance for key functionality. To some extent, the dependence of some urban municipalities on built-up district governance is seen as leaving them powerless and pointless. However, at times, municipalities have exercised their independence to try and improve their position vis-à-vis districts, often with some success. The most significant cases in which municipalities have been an obstacle to urban development are generally where viable rural municipalities unaffiliated with the urban district have resisted urbanisation, despite their land being important for urban growth. In these cases, the legal status and political organisation of erstwhile urbanising squatters has often taken on an outsized importance, and state and federal governments have sometimes gotten involved. This tendency has driven up the density of Dezevauni cities, as it has not been straightforward to acquire land for new urban development even at the best of times.

Urban planners, in practice, have considerable influence on the makeup of municipalities, however. Greenfield development (where rural land has been secured for urban purposes) can provide an opportunity to essentially determine the layout of communities before anyone actually lives there. Furthermore, when densification occurs, district-level governance may take the lead in suggesting lines along which to split large municipalities, though a popular vote is still necessary.

Public consultation

Though there may be the exercise of direct democratic powers at the municipal level, and to a lesser extent at higher levels of government, urban planning generally also involves direct consultation with the public. Direct feedback and communication can help provide clarity and transparency. Direct consultation with the public is more about communication and information than about formal decisionmaking powers, but it nonetheless has considerable significance in the process. Methods of consultation include through media (such as television, posters, the Internet), through meetings with planners and their representatives in person (often in tandem with municipal, neighbourhood or building meetings), focus groups, polling, temporary information kiosks and so forth; different agencies use different methods depending on the circumstances. Perhaps the most civically central method of consultation is still through the information and materials provided to weekly municipal/neighbourhood meetings.

Key principles and ideology

The discipline and consequently the practice of urban planning in Dezevau is aligned with a number of key ideas, some prescribed by government, some variable between urban planners. Internationally, the urban planning consensus model within Dezevau is identified as the Dezevauni school; it is characterised by the prominence of radical elements such as local power and socialist egalitarianism, planned in detail. There is significant contact between Dezevauni and international urban planning, especially the socialist world, such that foreign theory is key. To an extent, the Dezevauni academy and federal government encourage cross-pollination or homogeneity within urban planning in Dezevau. There is, however, significant internal variation, by region, by level of government, by political ideology, and so forth.

Equity

Perhaps the most important principle is that of equity, a key part of the socialist ideological system overall. Its exact application can be difficult because of variation by person and place; the principle is balanced with practical outcomes, which ought not be hamstrung by overzealous ideological fastidiousness. Debates between equality of opportunity and outcome also play into urban planning as they do in Dezevauni politics generally, undergirded by the concept of human rights; this is especially prominent because of the significance of urban planning to the governance system in Dezevau. In the past, a more productivist ethos has been overtaken by a focus on quality of life, as Dezevau has developed into a demographically stable and industrialised society.

Informed by studies of urban issues around the world including environmental classism and racism, ghettoisation, privatisation of public space, segregation, suburbanisation, urban decay and gentrification, urban planners consider a wide variety of potential impactors on urbanism. It has been suggested (at times, to its detriment) that urban planning is more international a discipline in Dezevau than anywhere else in the world because of these kinds of studies. Equity in an urban context is closely connected to the concept of the freedom of the city (discussed below), though it raises more points which are specific to the scale of the city, whereas equity is a more general, overarching concern.

Another key concern when considering equity is the differing needs and experiences of different people and groups. Closely related to the concept of pluralism, difference is not necessarily inequality where opportunity was duly afforded. Mobility in employment, residential location, household structure, culture (and generally other aspects of political geography) are therefore important to urban planning, as ideally affording but not determining different urban experiences.

Though not strict categories, urban planners commonly consider characteristics such as age, culture, gender, location, migratory status (i.e. whether one is a resident of the city or not), familial situation and class to ensure that equity is being done. Public consultation is an important way of discovering and raising concerns which might fail to be expressed via government.

Autonomous placemaking

A formal principle of Dezevauni urban planning is that places should essentially created under the power of the communities that inhabit them. This general principle developed, through the influence of radical, participatory notions of democracy in the 1980s and 1990s, out of older policies and principles such as settlement formalisation and democratic municipal founding.

The principle is contested insofar as municipalities do not get absolute power, and also insofar as the legal definition of municipalities does not necessarily map well to concepts such as community and place. However, it is generally given that basic decisions about places, such as its layout and decoration, should be made by the community of inhabitants, whensoever possible. The undergirding point is not that such decisions are crucial to the actual characteristics of a place, but that true democracy and freedom involve having a say about such things. Autonomous placemaking is held to be a good decisionmaking process for the makeup of the physical environment, as far as inhabitants know their own wants and needs well, but the irreplaceable aspect of autonomous placemaking is the psychological and political impact—of a space being turned into a place for its inhabitants, and one in which they have an investment, an attachment, and a sense of ownership. The discourse used by local communities to argue for expansions or maintenance of their powers tends to merge both justifications.

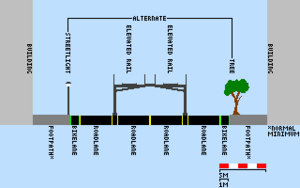

Settlement formalisation has been the most visible aspect of autonomous placemaking, even as it was first a significant phenomenon in the 1940s owing to a lack of resources to pursue physical development. The maintenance and upgrading of what were previous informal settlements, squats or slums has shaped Dezevauni cities perhaps more than any other single policy, as well as having significant implications for topics such as neighbourhood or municipal politics, riot policing, localism, infrastructural development, demography and tourism. Even after many decades, it is visible in terms of the organic shape, locally distinct style and community continuity of neighbourhoods; the archetypal Dezevauni urban neighbourhood tends to be dense, medium-rise, mixed-use, walkable, interspersed with public spaces, and tightly interwoven with local public transit. International interest in this highly visible practice has intensified in recent years, arguably a result of global trends in institutional decentralisation.

Temporal planning

An early innovation in Dezevauni urban planning, influenced by then-novel concepts such as the 24-hour city and shift work, is the idea of planning on a temporal (and not just spatial) scale. Plans, of course, consider what may happen over years in terms of demography, economic growth, environmental variations and so forth, but temporal planning made the aspect of time more explicit, and asked how planning was to account for variations over minutes, hours, days and seasons. In the 1950s, this was a relatively novel and radical concept; what might be a single space (e.g. a hall) was seen as capable of doubling up as several places (e.g. a conference room, a ballroom, a nightclub, a shelter), especially given the lack of the strictures of private property. At first, temporal planning was mainly seen as a way to multiply the efficiency of the built environment, but it quickly became about a broader conception of different people's differing usages of space over time. This principle was conceptually connected to the traditional functions of the ganome, which was an institution which was a place for childcare, cooking, eating, recreation and sleep at various times of the day, involving different numbers and kinds of people at different times even as it was an institution which touched virtually everyone in the immediate community.

Radical notions about 24-hour shift work arose but were quickly discarded in the 1950s, as concerns about social cohesion and solidarity joined with scientific concerns about the effects of daylight and the necessity of regular rest. Since then, temporality has been a relatively uncontroversial but explicit consideration in Dezevauni urban planning. Though the flexibility of space is now much more widely considered internationally, and is especially uncontroversial in more civically-minded systems, the ubiquity and fundamentality of the consideration in Dezevauni urban planning culture is credited with its strong urban planning in areas such as nightlife, planning for diversity (such as by age or neurodiversity), civil freedoms (such as protest) and transport accessibility.

Urbanism and urbanisation

Urban planning in Dezevau, because of the presence of certain radical trends, had to contend with questions of what a city was, and whether they should exist at all (in a politico-economic sense). Early on (up until the 1960s), alternative models for development included decentralising industry and commerce to towns and villages, or aligning them linearly, to aid in accessibility and transport access. There were also less fundamental debates about how big cities ought to be, whether it was better to have them benefit from the greatest economy of scale or to distribute more smaller cities. All of this was influenced by a sense of urban identity and cultural and political significance which survived from the premodern period.

Modern Dezevauni urban planning has receded from seriously debating the existence of cities at all, given their establishment. However, it still considers the function and purpose of cities in a societal context, in contrast to non-urban places and spaces such as agricultural countryside, parks and industrial installations. Cities are seen as necessary to house a large and growing population at an acceptable standard of living, at a density which will allow for the preservation of other land uses (such as farming and conservation). Urbanisation also promotes a concentration of available goods and services which benefits its inhabitants. The kind of intense development seen in cities is also necessary for the complex and highly productive processes of industry and research to occur; cities are engines for the manufacture of modern goods and knowledge. Hence, urbanisation is promoted and seen as desirable as far as it fulfils these goals, but may be curtailed where it does not serve these purposes (such as when sprawl intrudes on agricultural land).

Such broad considerations about the role of urbanisation were historically often made at the state level, but are now made at a federal or similar level; such large-scale decisions require high-level balancing. However, the overall level of control over urbanisation has greatly reduced, as rates of urbanisation and population growth have slowed, and emphasis on individual choice and local power has increased. The critique has been made that urbanisation is no longer examined, with the political centrality and accessibility of cities meaning that they are conceived of as "default" spaces for any and all development and human activity.

Freedom of the city

The concept of freedom of the city was a relative newcomer, emerging among other radical ideas in the leadup to and during the Cultural Revolution. It developed primarily out of the idea of the right to the city (the terms being the same in Ziba). It came into the mainstream as the notion of the city became more and more secure under a maturing system of urban planning. It argued that cities were communities themselves, and spaces with special positive social characteristics, not merely hosts to dense populations and high-intensity economic activity. The emergence of the freedom of the city was a rebellion against the enclosure of spaces for gated communities, industry, military or other special uses, and so forth; at its core, it was about the idea that people in a city had a fundamental right to move around it and interact with its life. Cities, it was proposed, were places uniquely suited to the exercise of radical freedom, for the majority of the population, and thus it was important to plan cities for more than production and the provision of services to localities. Policies related to this include free (or low cost) public transportation at all spatial scales, and allowing for unrestricted urbanisation via the gogous.

Freedom of the city was influential and popular among urban planners and urban populaces from the 1980s onwards, but its nebulousness meant that it began to lose coherence as a concept quickly, in the same way that the right to the city became diluted. As a theoretical tool, it began to be supplanted by the more sober idea of freedom of movement as early as the 1990s, as well as a refocusing on non-urban living as urbanisation slowed and lifestyle deurbanisation grew in significance. Nonetheless, it remained an important rallying cry and waypoint in the history of urban planning ideology; it is still studied at the tertiary level by urban planning students.

Death of the city

While not an accepted principle, or a principle per se, a number of approaches within Dezevauni urban planning have deemphasised the traditional importance or conception of the city, as an identifiable space surrounded by non-urban space. It has been pointed out that advancements and changes such as high speed rail, air travel, the Internet, remote work, automation, suburbanisation and a general increase in population density have erased many of the normal boundaries of cities. Distance means less when travel from one city to another is rapid, and depends more on infrastructure than distance, while these kinds of commutes as well as remote and automated work means that they are also not labour markets composed of their inhabitants. In an informational sense, telecommunications have near erased city boundaries. These, combined with cities which are increasingly large, sprawling, polycentric areas, which sometimes touch each other or are broken up internally, have inspired alternative visions.

Perhaps the most mainstream method, recognised in many government processes and plans, is megalopolitan planning. Recognising the practical erasures of urban limits where they exist, megalopoleis are governed as collocations of urban area. There are still important elements in a spatial sense, such as for commuting, water supply and sanitation, environmental conservation, provision of services such as health and so forth. Megalopolis-scale planning has run up against political impediments because of district and state boundaries, but it is seen as better capable of tackling some regional issues in a coherent way. The most prominent megalopolis in Dezevau by far is Gavujuju, also known as the Bay of Lights megalopolis; a secondary one is the Doboadane megalopolis in the northeast (Mount Palmerston, Crescent Island City, New Begia, Biunhamao, etc.).

More radical notions also exist. The "death of the city" may be an overstatement for many of these notions, insofar as few argue for the total irrelevance of the city as a concept, only its decreased importance. Nonetheless, ideas such as "actually existing internationalism" examine globalisation, the Internet, climate change and so forth as everyday matters which should hence be the focus of everyday planning, as opposed to urban affairs. There is a general agreement among planners that there are broader issues which should intersect with urban planning, but these new approaches have generally not been politically or legally clarified, and may not be without the involvement of legislative authorities.

Communalisation

Though not an explicit principle so much as a trend, the progressive political tendency in Dezevau of communalising everyday life (away from atomic, family or private institutions) has been reflected throughout urban planning. Urban planning which assumed progressive and communal lifestyles was a self-fulfilling prophecy when people adjusted to their built environment, such as in terms of common spaces in housing or public recreational spaces. This was linked to the relatively communalised lifestyle common to Geguoni villages, from where most urban immigrants came. Urban planning as a form of advocacy or tutelage later on (after the Cultural Revolution or so) later became an explicit approach among some urban planners, though such an approach was not without critics. Gradually, as urban planning has become more democratic and less the preserve of a small and select professional caste, planning has taken on a less politically educatory position and a more popular one; this has seen urban planning reflects the dominant extent of communalisation (and thus reinforce it), while it has receded in other topics which are not so popular.

Evaluation

Dezevau is generally considered to be a positive example of the application of urban planning, in terms of the degree of care put into the configuration of the urban environment, and in terms of the democratic process involved. It is prominent internationally for both the way in which urban planning is done, and the prominence which it has in the administrative and governmental process. However, there are also significant criticisms, especially internally, of the costs and unsystematic results which Dezevauni urban planning involves. Disagreements between municipalities, districts, regions or states can produce unnecessary reduplication or costly conflict, and in general there is a lot of expenditure and time spent on the planning process which some argue could be put to better use. Some studies suggest that Dezevauni economic growth is hampered by the strength of the urban planning perspective, as opposed to emphasis on environments for productivity. These criticisms, it has been noted, are generally similar to those levelled at other systems (including in non-socialist countries), especially federal ones, around the world. Some have labelled such criticisms anti-democratic.[1]

Influence internationally

Dezevauni urban planning, its consensus stances known internationally as the "Dezevauni school", has some influence in socialist and developing countries, such as Asase Lewa and Nirala. Though not as associated with specific visionaries or architectural styles, Dezevau has stood as an example of the viability of democratic urban planning, in contrast to modernist grand plans. It has been a model for socialists and democrats both for its political nature as well as its economic characteristics, representing a stabler and less risky course to development.

Approaches to urban planning indigenous to the Global South took some time to mature (though there were early links with places like Rwizikuru), but after the 1980s, places like Asase Lewa adopted some of the essential characteristics of the Dezevauni school in ongoing urbanisation, such as autonomous placemaking prominently. Dezevauni planners played a prominent role in the planning of Amit Rahul Sidhu City, the capital of Nirala, including chief planner Godhoume Zengeve.

In Dezevau's immediate vicinity, however, most liberal states have pursued more modernist models, perceived as better for tourism and closer to the models of sponsors such as Senria and Euclean states. There have been elements which have been taken up, incompletely, however, such as temporal planning in Mabifia.

Gallery

See also

Bibliography

- Ziba Harmonisation Agency of Dezevau. 2019. Complete Harmonised Ziba Dictionary (2019). Government of Dezevau Press. <https://ziba.org/>.

References

- ↑ Modazo (2016). A Little Red Book: Council Democracy in Dezevau. University of Biunhamao. p. 95.