User:Luziyca/Sandbox: Difference between revisions

m (→Governance) |

m (→Design) |

||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

===Zerubaseŕiak=== | ===Zerubaseŕiak=== | ||

====Design==== | ====Design==== | ||

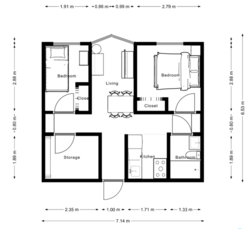

[[File:Zerubaseŕi_baten_antolamendua.png|250px|thumb|left|A typical layout of a zerubaseŕi]] | [[File:Zerubaseŕi_baten_antolamendua.png|250px|thumb|left|A typical layout of a flat in a zerubaseŕi]] | ||

The {{wp|khrushchyovka|zerubaseŕiak}} in the residential neighbourhoods of each hedapena were {{wp|prefabricated buildings}} made of concrete panels, designed for quick construction. This enabled each section to be built at a factory, and transported to the construction site. Most of the zerubaseŕiak were designed to be five storeys in height, as according to Lemovician building standards, this was the maximum number of floors that do not require an elevator, with any building higher than five storeys necessitating an elevator. However, in certain communities, primarily [[Goikoecija Beŕija]], [[Topagunea]], and [[Zubizurija]], zerubaseŕiak could go as high as twenty storeys in height, due to the higher populations in these areas compared to other municipalities in [[Lemovicia]]. | The {{wp|khrushchyovka|zerubaseŕiak}} in the residential neighbourhoods of each hedapena were {{wp|prefabricated buildings}} made of concrete panels, designed for quick construction. This enabled each section to be built at a factory, and transported to the construction site. Most of the zerubaseŕiak were designed to be five storeys in height, as according to Lemovician building standards, this was the maximum number of floors that do not require an elevator, with any building higher than five storeys necessitating an elevator. However, in certain communities, primarily [[Goikoecija Beŕija]], [[Topagunea]], and [[Zubizurija]], zerubaseŕiak could go as high as twenty storeys in height, due to the higher populations in these areas compared to other municipalities in [[Lemovicia]]. | ||

Revision as of 07:06, 29 December 2021

The Hedapenak (expansions) is the name for an early 1990s project by the separatist Lemovician government to build new cities to accommodate internally displaced persons as a result of the Lemovician War.

History

Background

At the end of the Lemovician War in June 1992, Lemovicia faced many challenges. One problem was that most Lemovician during the war fled from West Miersan-held territory, leading to the establishment of IDP camps to house the internally displaced Lemovicians. Conditions were poor, despite efforts by the Lemovician government to improve conditions in the camps, leading to the government beginning to draft plans for the scheme.

Another problem was that much of Lemovicia's infrastructure had been destroyed by the fighting during the Lemovician War, meaning that the supply of housing was low, while few industries were able to operate. This hindered the ability of the Lemovician government to resettle the internally displaced persons within Lemovician territory, while the lack of jobs meant that many Lemovicians in neighbouring countries, such as Bistravia, Champania, and East Miersa were less likely to return to Lemovicia.

Finally, due to its political status, few countries had diplomatic relations with Lemovicia, while sanctions imposed upon it by the West Miersan government hindered the ability of the Lemovician government to import necessary supplies to help rebuild the country. One official warned that "without coordinated international support, Lemovicians will continue to suffer the after-effects of the Lemovician War for generations to come."

Early planning

Planning for the scheme began in March 1988 after the fall of Hoikoćija (Goikoecija in Lemovician) in Operation Zemsta, as the fall of the city and of Ibaiak Province by the end of the year, due to virtually all the Lemovicians in Hoikoćija fleeing to Lemovicia. This influx, combined with the failure of the Revolutionary Defence Forces to recover Ibaiak Province put pressure on the Lemovician government to organise a "medium-term resettlement scheme," as the IDP camps were deemed to be "completely unsatisfactory for the development of a socialist society." Alac Muru would play a significant role in outlining plans for residential and industrial neighbourhoods.

While by 1990, several sites were shortlisted for what would become Goikoecija Beŕija, including the Gereziondoa Cooperative Farm (named after the Wiśniowskis who owned the land prior to 1979), planning for other parts of the Hedapenak programme would only begin in earnest, as the Lemovician government began to work on post-war recovery plans: as many houses and factories were damaged or destroyed over the course of the Lemovician War, it was also important for the Lemovician government to provide quality housing to the Lemovicians. This meant that the government began eying vacant land (i.e. land owned by Miersans who fled during the war) or cooperative farms for repurposing into hedapenak for neighbouring towns and villages.

By July 1992, a preliminary plan was approved for the Hedapenak programme: with the exception of Goikoecija Beŕija, which was to be built on the Gereziondoa Cooperative Farm, new neighbourhoods were to be built in Topagunea, Zubizurija, Ecijehaŕa, Gotor, Sardeśkak, and Burdina, while certain communities that were "almost or entirely destroyed by the Lemovician War," such as Heŕibeŕija, were to be rebuilt entirely.

Construction

With the institution of the preliminary plan, time was of the essence: in October 1992, Ociote Sasiambarena held a groundbreaking ceremony on the site of Goikoecija Beŕija, with Sasiambarena saying that "we have an obligation to all Lemovicians whose homes and workplaces have been destroyed during the war to complete this quickly, so that they can live with dignity."

Construction began quickly, even before the plans for the hedapenak were finalised by the National Assembly in January 1993, as the Lemovician government prioritised reconstruction of the country following the Lemovician War. With the formal approval of the hedapenak programme in January 1993, the Lemovician government quickly began construction of other hedapenak throughout the country, with the primary priority first being towards reconstructing housing, and the secondary priority being to construct workplaces. Many of the zerubaseŕiak would be completed in a matter of months, due to the panel design of each zerubaseŕia, with several models of zerubaseŕiak being used.

On 21 November 1994, just over two years after the groundbreaking ceremony in Goikoecija Beŕija, Ociote Sasiambarena opened Goikoecija Beŕija to the internally displaced persons from Hoikoćija. At the time that it was opened, five residential neighbourhoods and one industrial neighbourhood were completed, with a designed population of 10,000 people, although several more residential neighbourhoods were under construction when Sasiambarena opened the city.

Despite the opening of Goikoecija Beŕija in 1994, construction continued in most hedapenak, although by 1996, construction began to slow down in the hedapenak as all the internally displaced persons have been resettled, and the housing shortage ceased being a significant issue to Lemovicia. By 1999, construction of new residential neighbourhoods had effectively ceased, and in May of that year, the Chairman of the Presidency at the time, Patryk Krawczak declared that "the hedapenak programme has fulfilled its purpose" in resettling Lemovicians in "better housing."

Layout

Neighbourhoods

Each area built in the Hedapenak programme is divided into neighbourhoods (Lemovician: auzoak). The neighbourhoods within each hedapena (expansion) were divided into two categories: the residential neighbourhoods (bizitegi-auzoa) and the industrial neighbourhoods (śemisoba-auzoa).

The residential neighbourhoods were to be arranged akin to a microdistrict in TBD. The residential neighbourhoods would contain zerubaseŕiak to be built in the neighborhoods, with shops, schools, parks, playgrounds, cafeterias, and clinics. Many of the zerubaseŕiak were five storeys in height, although in Goikoecija Beŕija, Topagunea, and Zubizurija, zerubaseŕiak could go as high as twenty storeys in height. The residential neighbourhoods were designed to accommodate between 1,000 and 2,000 people within an area between 10 hectares and 100 hectares.

The industrial neighbourhoods were generally designed around one or more factories, mills, coal and iron mines, or offices, with facilities catering to the workplaces in these neighbourhoods being concentrated within industrial neighbourhoods, such as transport hubs, cafeterias, and dormitories for temporary workers not resident within the area. To ensure the most efficient distribution of these neighbourhoods, and to reduce the likelihood of unemployment, the preliminary plan stated that there was to be one industrial neighbourhood for every five residential neighbourhoods, so that there were enough workers to work within the industrial neighbourhoods: this suggests that the ideal population needed to fill the labour pool in an industrial neighbourhood is between 5,000 and 10,000 people.

In addition to these two main types of neighbourhoods, there is a central neighbourhood (erdiko-auzoa) in areas which had no discernable city centre prior to the hedapenak programme, or were otherwise "completely devastated" during the Lemovician War, with the intention of serving as city centres for the community as a whole. The central neighbourhoods feature amenities such as hospitals, town halls, department stores, a plaza, a stadium, and a Lemovician Episemialist church.

Zerubaseŕiak

Design

The zerubaseŕiak in the residential neighbourhoods of each hedapena were prefabricated buildings made of concrete panels, designed for quick construction. This enabled each section to be built at a factory, and transported to the construction site. Most of the zerubaseŕiak were designed to be five storeys in height, as according to Lemovician building standards, this was the maximum number of floors that do not require an elevator, with any building higher than five storeys necessitating an elevator. However, in certain communities, primarily Goikoecija Beŕija, Topagunea, and Zubizurija, zerubaseŕiak could go as high as twenty storeys in height, due to the higher populations in these areas compared to other municipalities in Lemovicia.

The typical layout of each flat within a zerubaseŕi include two bedrooms with closets attached, a bathroom, a storage room, and a combination living room and kitchen, with hallways connecting the rooms with one another. Overall, the average area in an individual zerubaseŕi two-bedroom flat is 46 square metres (501 square feet). However, smaller zerubaseŕi exist with only one bedroom, bathroom, and a combination living room/kitchen, and larger zerubaseŕi exist with three bedrooms, a bathroom, a storage room, and a combination living room/kitchen. All flats in a zerubaseŕi have a connection to water and sewer systems, electricity, central heating, and to waste disposal.

On the lower floors of zerubaseŕiak, primarily the ground floor, space is often made for the use of the residents within a zerubaseŕi. Common amenities include a conference room for the board, a rec room and a gym, although libraries, internet cafes, daycares, and convenience stores are often found in many, but not all zerubaseŕiak.

Governance

While zerubaseŕiak were built by the Lemovician government as part of the Hedapena programme, when residents settled in a zerubaseŕi, ownership was transferred from the state to a board (Lemovician: zerubaseŕiko-taula) elected by all residents in a given zerubaseŕi 16 years or older, to serve a one year term.

The typical composition of a board is comprised of five members, with four representing the floors inhabited by residents in a given zerubaseŕi, and one being elected at-large by all the residents in a given zerubaseŕi. However, in cases where a zerubaseŕi has more floors than the average five storeys, it may have as many as twenty members, of whom nineteen represent the residents on a given floor. Regardless of the circumstances, all members are equal, although in practice, each session is chaired by someone who rotates among the members with each session.

The responsibility of each board is to maintain the building "to government standards," to organise activities for the residents within a given zerubaseŕi, to approve of businesses or cooperatives to operate on the ground floor, and to implement restrictions, such as the prohibition of smoking or drinking within a zerubaseŕi. As well, members of the board can select a delegate from any of the residents to represent their particular zerubaseŕi on the district council.

Like all elected officials in Lemovicia, including the National Assembly, board members are bound by imperative mandates, and if enough residents are dissatisfied with either their "floor representative" or their zerubaseŕi representative on the board, recall elections must be held. Despite these safeguards against abuses of power, complaints have arisen over the years of boards in certain zerubaseŕiak becoming "too entrenched" and unwilling to address residents' concerns, which have led to proposals for reform to eliminate the "little lords" as some derogatorily call the boards, or to otherwise curtail their powers.

(TBC)