Choe Sŭng-min: Difference between revisions

m (1 revision imported) |

No edit summary |

||

| (9 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox officeholder | {{Infobox officeholder | ||

|name = Choe Sŭng-min | |name = Choe Sŭng-min | ||

|image = | |image = Horii_Tomitaro.jpg | ||

|caption = Official portrait of Choe Sŭng-min, taken in 1988 | |caption = Official portrait of Choe Sŭng-min, taken in 1988 | ||

|honorific-prefix = His Excellency | |honorific-prefix = His Excellency | ||

| Line 11: | Line 10: | ||

|primeminister = | |primeminister = | ||

|term_start = 25 May 1988 | |term_start = 25 May 1988 | ||

|term_end = | |term_end = 17 February 2021 | ||

|predecessor = ''Position created'' | |predecessor = ''Position created'' | ||

|successor = | |successor = [[Kim Pyŏng-so]] | ||

|office1 = General-Secretary of the Menghean Socialist Party | |office1 = General-Secretary of the Menghean Socialist Party | ||

|order1 = 2nd | |order1 = 2nd | ||

|president1 = | |president1 = | ||

|term_start1 = 23 July 1992 | |term_start1 = 23 July 1992 | ||

|term_end1 = | |term_end1 = 17 February 2021 | ||

|predecessor1 = Go Hae-wŏn | |predecessor1 = Go Hae-wŏn | ||

|successor1 = | |successor1 = [[Mun Chang-ho]] | ||

|office2 = Supreme Commander of the Menghean Armed Forces | |office2 = Supreme Commander of the Menghean Armed Forces | ||

|order2 = | |order2 = 1st | ||

|term_start2 = 25 May 1988 | |term_start2 = 25 May 1988 | ||

|term_end2 = | |term_end2 = 17 February 2021 | ||

|predecessor2 = | |predecessor2 = ''Position created'' | ||

|successor2 = | |successor2 = [[Kang Yong-nam]] | ||

|office3 = Chairman of the Interim Council for National Restoration | |office3 = Chairman of the Interim Council for National Restoration | ||

|order3 = | |order3 = 2nd | ||

|primeminister3 = | |primeminister3 = | ||

|term_start3 = 1 March 1988 | |term_start3 = 1 March 1988 | ||

| Line 41: | Line 40: | ||

|successor4 = | |successor4 = | ||

|birth_name = Choe Jun (최준 / 崔俊) | |birth_name = Choe Jun (최준 / 崔俊) | ||

|birth_date = {{Birth date|1939| | |birth_date = {{Birth date|1939|12|12|df=y}} | ||

|birth_place = Gyŏngwŏn-ri, upper Chŏnro Province, Menghe | |birth_place = Gyŏngwŏn-ri, upper Chŏnro Province, Menghe | ||

|blank1 = Ethnicity | |blank1 = Ethnicity | ||

|data1 = [[Meng]] | |data1 = [[Meng]] | ||

| | |death_date = {{death date and age |2021|2|17 |1939|12|12 |df=yes}} | ||

| | |death_place = [[Donggyŏng]], Menghe | ||

|death_place = | |||

|restingplace = | |restingplace = | ||

|restingplacecoordinates = | |restingplacecoordinates = | ||

|spouse = | |spouse = Cho In-hye (1971-1972) | ||

|partner = | |partner = | ||

|children = none | |children = none | ||

|occupation = {{wp| | |occupation = {{wp|Revolutionary}} {{wp|Aide-de-camp|aide-de-camp}}, {{wp|Officer_(armed_forces)|military officer}}, {{wp|Politician|statesman}} | ||

|party = [[Menghean Socialist Party]] | |party = [[Menghean Socialist Party]] | ||

|allegiance = {{flag|Menghe}} | |allegiance = {{flag|Menghe}} | ||

|branch = Menghean People's Army (1963-1987)<br>[[Menghean Army]] (1988-present) | |branch = Menghean People's Army (1963-1987)<br>[[Menghean Army]] (1988-present) | ||

|serviceyears = | |serviceyears = 1963-2021 | ||

|rank = Supreme Commander | |rank = Supreme Commander | ||

|commands = Menghean Armed Forces | |commands = 24th Mechanized Division (1983-1988)<br>Menghean Armed Forces (1988-2021) | ||

|battles = [[Menghean War of Liberation]]<br>[[Decembrist Revolution]] | |battles = [[Menghean War of Liberation]]<br>[[Decembrist Revolution]] | ||

|awards = | |awards = | ||

| Line 67: | Line 65: | ||

''This is a [[Meng]] name; the family name is Choe.'' | ''This is a [[Meng]] name; the family name is Choe.'' | ||

'''Choe Sŭng-min''' ([[Menghean_language#Sinmun|Menghean Sinmun]]: 최승민, [[Menghean_language#Gomun|Menghean Gomun]]: 崔承民, pr. [t͡ɕʰwe̞.sɯŋ.min]; | '''Choe Sŭng-min''' ([[Menghean_language#Sinmun|Menghean Sinmun]]: 최승민, [[Menghean_language#Gomun|Menghean Gomun]]: 崔承民, pr. [t͡ɕʰwe̞.sɯŋ.min]; 12 December 1939 - 17 February 2021), known in his early life as '''Choe Jun''' (최준 / 崔俊), was a military commander and statesman who served as the {{wp|Supreme_leader|supreme leader}} of [[Menghe]] for 33 years from 1 March 1988 until his death in 2021. He played a pivotal role in the [[Decembrist Revolution]] of 21 December 1987, which established the Socialist Republic of Menghe with Choe as its first leader. While in office, he oversaw a period of rapid economic growth known as the [[Menghean economic miracle]], as well as the modernization of the Menghean armed forces. Because of his role in founding a new state and strengthening the country's military and economy, Choe is widely regarded in Menghe as the country's greatest modern leader, though he remains controversial internationally for his role in engineering an authoritarian regime. | ||

Choe began his career in the military, | Choe began his career in the military, serving as a message-runner for General Baek Gwang-hyun during the [[Menghean War of Liberation|War of Liberation]]. It was during this time that he adopted the given name Sŭng-min. After a brief return to civilian life, he enrolled in the [[Menghean National Defense Academy]] in 1967, graduating into the Menghean People's Army. Despite fighting in the War of Liberation and serving in the armed forces, Choe was an ardent nationalist who disagreed with many of the cultural policies of the Menghean People's Communist Party, which ruled what was then the [[Democratic People's Republic of Menghe]]. After [[Ryŏ Ho-jun]] came to power, Choe began circulating dissident literature through the Menghean People's Army under the pen name Suk Su-dŏk, earning a reputation among other nationalist officers. | ||

In the early morning hours of December 21st, 1987, Choe Sŭng-min disobeyed an order to clear out a crowd of famine refugees, instead dispatching troops of his 12th Tank Division to storm the headquarters of the Menghean People's Communist Party in a coup widely known as the [[Decembrist Revolution]]. In the [[Interim Council for National Restoration]] which led the country after the coup, Choe was second in command to Marshal Baek Gwang-hyun, who had played a less prominent role in the events of December 21st but held a higher military rank. He ousted Marshal Baek in a {{wp|self-coup}} on March 1st, emerging as the most important post-coup leader when the new government formed on 25 May 1988. In the years that followed, Choe continued to expand his monopoly on political power, purging potential rivals and anyone suspected of loyalty to Ryŏ Ho-jun's ousted Populist faction. In 1993, he took direct control over the [[Menghean Socialist Party]], cementing his position as an entrenched absolute ruler. During the late 1990s, he built a strong [[Choe Sŭng-min's cult of personality|personality cult]] which emphasized his leading role in the Decembrist Revolution and the [[Economic reform in Menghe|economic reforms]] that followed. This period coincided with the [[Disciplined Society Campaign]], Choe's effort to reshape society in his image. | |||

After losing face in the [[Polvokian Civil War]], the [[1999 Menghean financial crisis]], and the [[Chimgu nuclear accident]], Choe transitioned to a more decentralized leadership style in the mid-2000s, allowing his subordinates to take a more active role in policymaking while he withdrew to a somewhat more symbolic role. Nevertheless, Choe Sŭng-min concurrently held the posts of [[Supreme Council of Menghe|Chairman of the Supreme Council of Menghe]], [[Menghean Socialist Party|General-Secretary of the Menghean Socialist Party]], and Supreme Commander of the Menghean Armed Forces until his death, and state propaganda widely credited him with engineering the country's military and economic achievements in the 2000s and 2010s. In the late 2010s, his health began to worsen, and he periodically disappeared from public view for weeks at a time, leading to a covert power struggle as his various number-two officials vied for influence. Choe Sŭng-min was pronounced dead on 17 February 2021 at 11:52 PM, after suffering a series of heart attacks; at his [[Death and state funeral of Choe Sŭng-min|state funeral]], he was pronounced a [[Chŏndoism#S.C5.8Fngindan|Sŏng'in]], and later that year, work began on several temples in his name. | |||

==Early life== | ==Early life== | ||

Choe Sŭng-min's father, Choe Jŏng-sŏk, was a mid-size {{wp|Land_tenure|landowner}} who employed {{wp|Tenant_farmer|tenant laborers}}, but in a relatively impoverished area of the country: Gyŏngwŏn-ri, Gangsŏng County, in upper Chŏllo Province near the city of Kaesan. As military service was the most promising route up the social ladder in the [[Greater Menghean Empire]], | Choe Sŭng-min's father, Choe Jŏng-sŏk, was a mid-size {{wp|Land_tenure|landowner}} who employed {{wp|Tenant_farmer|tenant laborers}}, but in a relatively impoverished area of the country: Gyŏngwŏn-ri, Gangsŏng County, in upper Chŏllo Province near the city of Kaesan. As military service was the most promising route up the social ladder in the [[Greater Menghean Empire]], Choe Jŏng-sŏk applied for the Imperial Menghean Naval Academy in 1933, but his application was turned down. He applied again in 1935, after the outbreak of the [[Pan-Septentrion War]] led to a surge in the demand for officers, and was accepted. After graduating in 1939, he married his fiancé, Pak Su-hyi, whom he had met in Sunju. That fall, while his wife was pregnant with his first son, he was summoned to a new post on the {{wp|heavy cruiser}} ''Chobosan''. | ||

His son, born on December 12th of that year, was named Choe Jun (최준 / 崔俊), in keeping with his father's wishes. As the war began to escalate in this period, Choe Jŏng-sŏk's {{wp|Leave_(military)|leaves}} became less and less frequent, but he wrote regular letters back to his wife. At home, Pak Su-hyi used her husband's stipend and officer status to hire a tutor for their son, and managed the family estate with her husband's elder brother, Choe Hae-sŏng. Tragedy struck in 1944, when the ''Chobosan'' was sunk | His son, born on December 12th of that year, was named Choe Jun (최준 / 崔俊), in keeping with his father's wishes. As the war began to escalate in this period, Choe Jŏng-sŏk's {{wp|Leave_(military)|leaves}} became less and less frequent, but he wrote regular letters back to his wife. At home, Pak Su-hyi used her husband's stipend and officer status to hire a tutor for their son, and managed the family estate with her husband's elder brother, Choe Hae-sŏng. Tragedy struck in 1944, when the ''Chobosan'' was sunk off the coast of Innominada. Choe Jŏng-sŏk, never found, was presumed dead. The economic situation on the home front added to Pak Su-hyi's hardship; skyrocketing inflation reduced her Military Widow stipend to a pittance and wiped out the value of her savings, and the conscription of Homeland Defense militia pulled more and more workers off of her farm. | ||

At the time of Menghe's surrender in November 1945, Choe Jun was nearly six years old and his family was already facing serious hardship. The situation intensified under the Occupation Authority's campaign to remove | At the time of Menghe's surrender in November 1945, Choe Jun was nearly six years old and his family was already facing serious hardship. The situation intensified under the Occupation Authority's campaign to remove elite families connected to the old regime, a policy which the rival Kim family exploited to confiscate the Choe family's land and property. Choe Jun's best friend, Meng So-hyi, died of hypothermia in January 1952, and his mother fell severely ill the same year. | ||

In | In March 1952, at the age of twelve, Choe left his hometown to seek out the 8th Army, which was resisting an Anglian offensive in Suksan province. By the time he had crossed the mountains to Wŏnsan, he was frail and sick as well as underage, and despite his protests the local partisans refused to allow him into their ranks. Purely by chance, however, Major General Baek Gwang-hyun was passing through the partisan camp at the time and heard news of the determined would-be recruit. Taking pity on the boy, Major General Baek upheld the judgment that he was unfit for front-line combat, but permitted him to serve as his personal messenger and {{wp|aide-de-camp}}. | ||

Unfortunately, Choe Jun's arrival coincided with a major Anglian offensive, and after one year of steadily ceding ground, General Yang Tae-sŏng decided to lead his remaining troops on the [[Menghean_War_of_Liberation#The_Eighth_Army.27s_retreat|Chŏnsan expedition]] to safe territory. Owing in part to his position at a top officer's side, Choe Jun survived the journey, arriving in the Sanhu region in September 1953. Propaganda accounts of this period credit the young Choe with a number of combat and commanding feats, including engineering an encirclement of Republic of Menghe Army forces in 1959, though independent histories of the period agree that he remained an aide-de-camp throughout the period and most likely never saw combat. Even so, Choe Jun (who adopted the given name Sŭng-min in 1959) impressed other officers with his vigor and determination, and his time in the headquarters of the 8th Army and the Menghean Liberation Army allowed him to forge ties with a number of other current and rising officers. | |||

==Under the DPRM== | |||

===At the Menghean National Defense Academy=== | |||

Choe Sŭng-min was 25 years old in July 1964, when the Republic of Menghe government formally surrendered to the Communist and Nationalist forces, ending the [[Menghean War of Liberation]]. Due to his military experience and extensive political connections, Choe was fast-tracked into the first postwar class of the [[Menghean National Defense Academy]]. This first graduating class, known as MNDA 1, was comprised of a mix of noncommissioned MLA veterans, the children of MLA officers, and other politically-connected individuals like Choe Sŭng-min himself. This once again proved essential in allowing Choe to to forge new ties and build up his reputation. | |||

Under the terms of the [[Sangwŏn Agreement]], then still in force, control of the Menghean National Defense Academy passed to the Nationalist faction among the officers, many of whom were veterans of the [[Pan-Septentrion War]]. While formally staying within boundaries set by the Menghean People's Communist Party, cadets' education also focused on nationalist themes, retelling the stories of military heroes in the last century and copying many training standards used under the [[Greater Menghean Empire]], including [[Fluid Battle Doctrine]]. Marxist ideological education, by contrast, was nearly absent from the curriculum during this period. | |||

This proved fortunate for Choe, who, according to one classmate, "actively modeled himself on the rigorous ideal of an officer in the Imperial Menghean Army, and even kept a portrait of [[Kim Myŏng-hwan]] in his dormitory, bowing to it every morning." He also had a framed photograph of his father in [[Imperial Menghean Navy|IMN]] uniform; though the two had only met intermittently in the years before the father's death, Choe Jŏng-sŏk was a profound role model for his son due to his determination to serve through the military and his sacrifice aboard the ''Chobosan''. Academy instructors, many of them veterans of the Pan-Septentrion War, admired Choe Sŭng-min's patriotism and discipline, and regarded him as a model cadet. | |||

Some biographers have argued that experience in the MNDA, especially in its earlier classes where veteran officers still exercised full control over training, was a deeply formative experience for Choe Sŭng-min and many of his fellow coup conspirators. In addition to instilling a strict sense of duty and diligence, MNDA experience brought a political message: that even with the People's Communist Party in control, the Army remained the backbone of the nation, and its soldiers and officers had a special responsibility to defend the nation's well-being. | |||

===In the Menghean People's Army=== | |||

The MNDA 1 class graduated in the spring of 1968. While on leave before his first assignment, Choe Sŭng-min visited his hometown in Gyŏngwŏn-ri, only to find that his mother had died in a counter-partisan {{wp|Search_and_destroy|search-and-destroy}} mission during the War of Liberation and his family's land had been taken over by the village revolutionary committee. Moreover, Gyŏngwŏn-ri and the surrounding area had experienced a bout of bubonic plague in the late 1950s, killing off close to a fifth of the population. With no living next-of-kin, Choe returned to Dongrŭng in a state of despair. | |||

After his return, Choe Sŭng-min was assigned to work as a regimental staff officer in the 48th Infantry Division. This unit was posted in Hyangchun, part of the 1st Army defending Menghe's northeastern coast. A rear-area division posted in a major city, the 48th Infantry was a common assignment for the well-connected and a comfortable place to be stationed; Choe often found himself heading into the famously beautiful city on temporary leave or official business. Still distraught from his return home, he chafed at this comfortable assignment, and repeatedly asked to be transferred to one of the divisions then intervening in [[Dzhungestan]]. His requests were denied, but they earned him the respect of his superiors. | |||

Choe Sŭng-min | |||

While stationed in Hyangchun, Choe Sŭng-min met Cho In-hye, the daughter of a local tailor. The two married in 1971, but Cho died of pneumonia the following year while pregnant with their first child, a daughter. Choe Sŭng-min once again fell into a state of depression, and was even granted medical leave to grieve his loss. During this period, he went into isolation in the mountains southeast of the city to watch over his late wife's grave. Having lost his childhood friends, his mother, his wife, and his daughter, he took an oath that he would not remarry, instead devoting the rest of his life to improving the country. | |||

Shortly after he returned to active duty, Choe Sŭng-min was promoted to Major and transferred to a battalion command position in the 12th Tank Division, which was posted outside the capital city of [[Donggyŏng]]. From there, personal connections, along with a continuing reputation for strict obedience and rigid discipline, helped Choe Sŭng-min climb through the ranks. In 1981 he was promoted to Colonel and assumed control of the 1202nd Regiment, and in 1984 he was promoted to Major-General and placed in command of the entire 12th Division. | |||

In anonymous interviews taken during the 2000s, soldiers who served under Choe described his leadership as "strict, but not ruthless." He had high expectations for his troops, and ran relentless drills, but never ordered beatings of soldiers under his command, a practice which was formally outlawed in 1964 but remained commonplace among more conservative officers. During the 1990s, though not often thereafter, Menghean propaganda credited Choe Sŭng-min with pioneering advances in Menghean military doctrine, but most foreign scholars consider his actual tactical expertise to be fairly minor, especially in the absence of actual combat experience. Carl Teller, a major historian of the early Choe era, described Choe as "the ideal peacetime officer - diligent, obedient, and able to pass review, if not combat." | |||

===Involvement in politics=== | |||

While stationed in the capital, Choe Sŭng-min grew more engaged in politics, which he saw as the best route to correct the dire poverty and inadequate medical services which had killed off his next of kin. He was highly supportive of [[Sim Jin-hwan]], who had assumed the post of General-Secretary in 1971. Sim's economic policy stressed rapid industrialization through the construction of large-scale state-run factories, which echoed the wartime policies of the Greater Menghean Empire. Though initially uninterested in the MPCP's ideology, Choe Sŭng-min grew enamored with Sim's brand of socialism, and considered leaving the military to join the Communist Party. His MNDA 1 classmates persuaded him to stay in the Army and to remain out of politics; the [[Sangwŏn Agreement]] was still in force, and under its terms, the Army and its active personnel were forbidden from engaging in politics. The Sangwŏn Agreement, however, was already under strain by the mid-1970s, and many other officers joined Choe in expressing support for the General-Secretary's work. | |||

Predictably, then, Choe Sŭng-min and his allies were deeply unsettled by the June 1980 internal coup in which [[Ryŏ Ho-jun]] replaced Sim Jin-hwan as General-Secretary. A member of the MPCP's Populist Faction, Ryŏ immediately set to work breaking up Sim's centralized factories and replacing them with a system of collectively owned small workshops. Still protected by the fragile Sangwŏn Agreement, the armed forces largely escaped Ryŏ's purges, but nationalists and statists in the MPA's upper ranks were infuriated by these changes. | |||

In 1981, after assuming command of the 1202nd Tank Regiment, Choe Sŭng-min began circulating a series of pamphlets under the {{wp|Pseudonym|pseudonymous}} name Suk Su-dŏk (숙수덕 / 肅修德). In these writings, he openly criticized Ryŏ's poor decisions, including his promotion of backyard steelmaking, his attacks on traditional culture, his relentless purges of Progress Faction members in the MPCP, and his [[Menghe and weapons of mass destruction|pursuit of nuclear weapons]]. Though the Suk Su-dŏk pamphlets were officially pseudonymous, their true provenance was something of an open secret among MNDA 1 graduates close to Choe Sŭng-min, and Choe avoided punishment mainly because nationalists higher in the Army's ranks stauchly blocked investigation efforts by the Ministry of State Security. | |||

==Rise to power== | ==Rise to power== | ||

{{main|Decembrist Revolution}} | {{main|Decembrist Revolution}} | ||

There is some disagreement over how important a role Choe Sŭng-min played in early preparations for the coup that would become Menghe's [[Decembrist Revolution]]. Official Menghean sources, and many of the co-conspirators who followed Choe to the new inner circle, assigned him a prominent role from the start, noting that although he was only a Major-General at the time, his pseudonymous writings were widely read and he had a strong reputation for disciplined loyalty to the country. Others, especially foreign historians, have argued that while Choe did have some importance in the pre-December conspiracy, he remained secondary due to his rank, and only emerged as the ringleader after he consolidated his power | There is some disagreement over how important a role Choe Sŭng-min played in early preparations for the coup that would become Menghe's [[Decembrist Revolution]]. Official Menghean sources, and many of the co-conspirators who followed Choe to the new inner circle, assigned him a prominent role from the start, noting that although he was only a Major-General at the time, his pseudonymous writings were widely read and he had a strong reputation for disciplined loyalty to the country. Others, especially foreign historians, have argued that while Choe did have some importance in the pre-December conspiracy, he remained secondary due to his rank, and only emerged as the ringleader after he consolidated his power in the interim government that followed. | ||

What is known is that Major-General Choe played a pivotal role in the 1987 coup as it actually unfolded. After his 12th Tank Division, stationed near Donggyŏng, was ordered to suppress protesting farmers in People's Square, Choe refused, knowing that compliance would lead to a massacre. In the pre-dawn hours of December 21st, he moved his troops toward the center of the city, but instead ordered them to seize control of Communist Party headquarters and related political buildings. With this improvised act, he moved the coup timetable ahead of schedule without waiting for the approval of higher officers, and quickly emerged as its de facto leader. | What is known is that Major-General Choe played a pivotal role in the 1987 coup as it actually unfolded. After his 12th Tank Division, stationed near Donggyŏng, was ordered to suppress protesting farmers in People's Square, Choe refused, knowing that compliance would lead to a massacre. In the pre-dawn hours of December 21st, he moved his troops toward the center of the city, but instead ordered them to seize control of Communist Party headquarters and related political buildings. With this improvised act, he moved the coup timetable ahead of schedule without waiting for the approval of higher officers, and quickly emerged as its de facto leader in the eyes of the public. | ||

After the so-called "revolution," Menghe fell under the leadership of the [[Interim Council for National Restoration]], a temporary body composed of the leading officers involved in the initial coup plot. Formally, this body was led by Marshal Baek Gwang-hyun, the highest-ranking officer among the conspirators. Despite their close relationship and past history in the War of Liberation, beneath the surface Baek and Choe soon fell into a tense struggle for political supremacy. Baek believed that his seniority in age and rank entitled him to the higher leadership position, while Choe, who had won greater public recognition for his role in the events of December 21st, feared that he was being sidelined amidst a return to the pre-coup order. The two also disagreed on the direction of the post-coup government, and in particular whether it was better to implement radical changes to the political and economic system or simply to restore the surviving members of [[Sim Jin-hwan]]'s faction. | After the so-called "revolution," Menghe fell under the leadership of the [[Interim Council for National Restoration]], a temporary body composed of the leading officers involved in the initial coup plot. Formally, this body was led by Marshal Baek Gwang-hyun, the highest-ranking officer among the conspirators. Despite their close relationship and past history in the War of Liberation, beneath the surface Baek and Choe soon fell into a tense struggle for political supremacy. Baek believed that his seniority in age and rank entitled him to the higher leadership position, while Choe, who had won greater public recognition for his role in the events of December 21st, feared that he was being sidelined amidst a return to the pre-coup order. The two also disagreed on the direction of the post-coup government, and in particular whether it was better to implement radical changes to the political and economic system or simply to restore the surviving members of [[Sim Jin-hwan]]'s faction. | ||

Tensions within the Interim Council came to a head on March 1st, 1988, when the headstrong Baek, impatient with Choe's constant resistance and feeling betrayed by his former loyal aide-de-camp, ordered his troops to arrest Choe Sŭng-min for insubordination. Informed of the plot | Tensions within the Interim Council came to a head on March 1st, 1988, when the headstrong Baek, impatient with Choe's constant resistance and feeling betrayed by his former loyal aide-de-camp, ordered his troops to arrest Choe Sŭng-min for insubordination. Informed of the plot by an MNDA 1 classmate in Baek's inner circle, Choe pre-empted the Marshal by organizing a news editorial excoriating Baek for his tacit approval of the suppression of the [[Menghean_famine_of_1985-87#1986|Chŏllo peasant uprisings]] in 1986. The day before Baek's arrest order went out, the state-run ''Labor Daily'' newspaper published the article as a front-page feature, and Choe ordered an investigation into the matter. This left Marshal Baek in an uncomfortable position; both the remaining Council insiders and the public at large suspected him of orchestrating a {{wp|self-coup}} to oust a widely popular revolutionary leader and prevent an investigation into his role in the famine. Chang In-su, the General famously stripped of his post after refusing to suppress the uprisings, weighed in against Baek, still resentful that the latter had not come to his aid in 1985. In defiance of Marshal Baek's orders, soldiers from the 12th Tank Division gathered outside the Donggyŏng residence where Choe Sŭng-min was staying to prevent his arrest, and crowds of protesters returned to People's Square to express their support for the Major-General. Outright opposition soon boiled over in the Interim Council itself, as even neutral and Baek-leaning officers accused the Marshal of abusing his power to eliminate one of their own. | ||

Aware that he had been outmaneuvered, Baek Gwang-hyun ordered his soldiers to stand down later in the afternoon, and resigned from his post as Chairman of the Interim Council. Three of his co-conspirators did the same, under pressure from Choe's soldiers. The remaining Council members held a special session immediately afterwards, unanimously electing Choe Sŭng-min as the new Chairman. Thus, while Marshal Baek had intended to eliminate one of his own rivals, his effort backfired: by the end of March 1st, Choe had emerged as the ''de jure'' leader of the Interim Council for National Restoration, with an even greater reputation among the officers and the general public. | Aware that he had been outmaneuvered, Baek Gwang-hyun ordered his soldiers to stand down later in the afternoon, and resigned from his post as Chairman of the Interim Council. Three of his co-conspirators did the same, under pressure from Choe's soldiers. The remaining Council members held a special session immediately afterwards, unanimously electing Choe Sŭng-min as the new Chairman. To ensure that no other higher-ranking officers might challenge him, the Council also promoted Choe to the specially created rank of ''Dae Wŏnsu'' (Supreme Marshal) and appointed him as Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. Thus, while Marshal Baek had intended to eliminate one of his own rivals, his effort backfired: by the end of March 1st, Choe had emerged as the ''de jure'' leader of the Interim Council for National Restoration, with an even greater reputation among the officers and the general public. | ||

The new government of the Socialist Republic of Menghe, formed on May 25th, 1988, gave Choe broad-reaching powers as Chairman of the [[Supreme Council of Menghe|Supreme Council]] | The new government of the Socialist Republic of Menghe, formed on May 25th, 1988, gave Choe broad-reaching powers as Chairman of the [[Supreme Council of Menghe|Supreme Council]]. Even so, it would take another five years before he fully consolidated his power as Menghe's "supreme leader" - a process which involved popular reforms such as the [[Agriculture_in_Menghe#Agricultural_reforms|decollectivization of agriculture]], targeted purges against DPRM loyalists and potential rivals, and a direct takeover of the [[Menghean Socialist Party]]. | ||

==Leadership== | ==Leadership== | ||

===Consolidation of power=== | ===Consolidation of power=== | ||

Choe Sŭng-min emerged in 1988 as Menghe's official head of state, but behind the scenes he remained something of a {{wp|Primus_inter_pares|first among equals}}. Despite his abrupt promotion to Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, he was still the youngest member of the [[Supreme Council of Menghe|Supreme Council]], in a culture that assigned great importance to seniority. He also faced a number of political rivals, including Go Hae-wŏn, the General-Secretary of the [[Menghean Socialist Party]]; Chang In-su, | Choe Sŭng-min emerged in 1988 as Menghe's official head of state, but behind the scenes he remained something of a {{wp|Primus_inter_pares|first among equals}}. Despite his abrupt promotion to Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, he was still the youngest member of the [[Supreme Council of Menghe|Supreme Council]], in a culture that assigned great importance to seniority. He also faced a number of political rivals, including Go Hae-wŏn, the General-Secretary of the [[Menghean Socialist Party]]; General Chang In-su, who had refused to suppress peasant uprisings during the [[Menghean famine of 1985-87]]; and Ro Gwang-hyi, a former colleage of [[Sim Jin-hwan]] who retained support among [[Sim_Jin-hwan#Industrialization_effort|''Jinjŏnpa'']] loyalists. | ||

Behind a facade of national unity, Choe carefully moved to eliminate the remaining threats to his power. He began by placing close allies and former subordinate officers in control of key ideological posts, including state media, which trumpeted Choe's role in the Decembrist Revolution and the return to household agriculture. He also organized the Inspect the Ranks Campaign, a sustained effort to identify unrepentant members of [[Ryŏ Ho-jun]]'s camp and remove them from public office. These moves still had strong support from his inner circle of rivals, who shared the goal of rooting out Populist-faction hardliners and drumming up public support for the new regime. | Behind a facade of national unity, Choe carefully moved to eliminate the remaining threats to his power. He began by placing close allies and former subordinate officers in control of key ideological posts, including state media, which trumpeted Choe's role in the Decembrist Revolution and the return to household agriculture. He also organized the Inspect the Ranks Campaign, a sustained effort to identify unrepentant members of [[Ryŏ Ho-jun]]'s camp and remove them from public office. These moves still had strong support from his inner circle of rivals, who shared the goal of rooting out Populist-faction hardliners and drumming up public support for the new regime. | ||

| Line 128: | Line 134: | ||

In September 1988, the special tribunal created to investigate Marshal Baek's crimes found him guilty of tacitly allowing the Chŏllo peasant uprisings to proceed, and of conspiracy to overthrow a fellow Council member. The latter crime was [[Capital punishment in Menghe|punishable by death]], but Choe Sŭng-min intervened and commuted his sentence to life under house arrest, allegedly in a show of mercy for his former mentor. This move temporarily reassured officials who had grown concerned about Choe's ambitions, and set the tone for the expanded purges which would follow. | In September 1988, the special tribunal created to investigate Marshal Baek's crimes found him guilty of tacitly allowing the Chŏllo peasant uprisings to proceed, and of conspiracy to overthrow a fellow Council member. The latter crime was [[Capital punishment in Menghe|punishable by death]], but Choe Sŭng-min intervened and commuted his sentence to life under house arrest, allegedly in a show of mercy for his former mentor. This move temporarily reassured officials who had grown concerned about Choe's ambitions, and set the tone for the expanded purges which would follow. | ||

Moving cautiously at first, Choe Sŭng-min steadily expanded the Inspect the Ranks Campaign to draw in higher-ranking officials, including some whose connection to Ryŏ was only indirect. In 1990, he orchestrated the arrest of over a hundred high-ranking government officials, claiming to have broken up a | Moving cautiously at first, Choe Sŭng-min steadily expanded the Inspect the Ranks Campaign to draw in higher-ranking officials, including some whose connection to Ryŏ was only indirect. In 1990, he orchestrated the arrest of over a hundred high-ranking government officials, claiming to have broken up a reactionary cell which had infiltrated the government. In their place, he appointed his own trusted allies, including a large number of MNDA 1 ex-classmates. For more entrenched rivals, he relied on other approaches; General Chang In-su, another popular hero, was pressured to retire in 1991 on account of his advanced age, and shortly afterward the [[National Assembly (Menghe)|National Assembly]] passed a law requiring that officers of General-grade ranks retire after turning 72. Choe's faction promoted this reform on the basis that it would prevent the military leadership from becoming senile, but its most important political effect was to free up a string of command and administrative positions in the coming years, displacing DPRM veterans and bringing in younger reformists. | ||

These shakeups in the government staff narrowed down the scope of potential rivals to Ro Gwang-hyi. The former Vice Chairman of the Politburo under [[Sim Jin-hwan]], he had been imprisoned in 1982 for his "productionist sympathies," and Choe himself had arranged for his release after the revolution. Initially the two men worked together, with Ro appointed Vice Chairman of the Supreme Council in 1988. Ro, having been forced out of power prior to the coup, needed a way to edge back into a position of influence, and Choe initially needed his endorsement in order to ensure the support of ''Jinjŏnpa'' supporters in the Communist Party. Yet by the early 1990s, Ro Gwang-hyi had shifted to an economically conservative stance, criticizing Choe's pragmatic swing toward pro-market reforms and the legalization of small private enterprises. These standoffs persisted until October 1992, when Ro was abruptly arrested on charges of exploiting the reform-era pricing system to enrich himself through the sale of plan-allocated goods on the market. Once again, state media sided overwhelmingly with Choe, revealing in dramatic terms Ro's hypocrisy in criticizing the widely successful reforms even as he engaged in corruption and embezzlement. Whether the charges were exaggerated remains unclear; such "dual-track resale" was widespread in the early reform period, and few officials in economic management positions could claim to have been innocent. | These shakeups in the government staff narrowed down the scope of potential rivals to Ro Gwang-hyi. The former Vice Chairman of the Politburo under [[Sim Jin-hwan]], he had been imprisoned in 1982 for his "productionist sympathies," and Choe himself had arranged for his release after the revolution. Initially the two men worked together, with Ro appointed Vice Chairman of the Supreme Council in 1988. Ro, having been forced out of power prior to the coup, needed a way to edge back into a position of influence, and Choe initially needed his endorsement in order to ensure the support of ''Jinjŏnpa'' supporters in the Communist Party. Yet by the early 1990s, Ro Gwang-hyi had shifted to an economically conservative stance, criticizing Choe's pragmatic swing toward pro-market reforms and the legalization of small private enterprises. These standoffs persisted until October 1992, when Ro was abruptly arrested on charges of exploiting the reform-era pricing system to enrich himself through the sale of plan-allocated goods on the market. Once again, state media sided overwhelmingly with Choe, revealing in dramatic terms Ro's hypocrisy in criticizing the widely successful reforms even as he engaged in corruption and embezzlement. Whether the charges were exaggerated remains unclear; such "dual-track resale" was widespread in the early reform period, and few officials in economic management positions could claim to have been innocent. | ||

| Line 136: | Line 142: | ||

===Personality cult=== | ===Personality cult=== | ||

{{main|Choe Sŭng-min's cult of personality}} | {{main|Choe Sŭng-min's cult of personality}} | ||

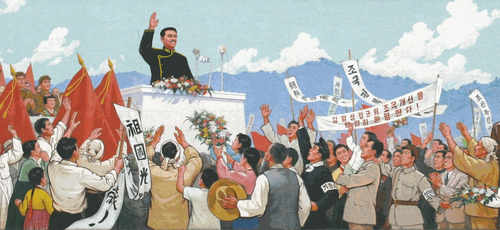

[[Image:Choe_Propaganda_Poster_2022-02-04.png|500px|thumb|right|"Marshal Choe Sŭng-min Greets the People at Anchŏn," a propaganda painting made in 1995.]] | |||

After consolidating his power, Choe Sŭng-min moved to capitalize it by developing a powerful {{wp|cult of personality}}. This was most notable in the wake of the Second Party Congress, which cemented his control over Party teachings, but even in the late '80s state media already presented idealized accounts of his role in the Decembrist Revolution and the privatization of agriculture. | After consolidating his power, Choe Sŭng-min moved to capitalize it by developing a powerful {{wp|cult of personality}}. This was most notable in the wake of the Second Party Congress, which cemented his control over Party teachings, but even in the late '80s state media already presented idealized accounts of his role in the Decembrist Revolution and the privatization of agriculture. | ||

| Line 143: | Line 150: | ||

While foreign intellectuals have generally derided Choe's personality cult as exaggerated and blatantly propagandized, it has gained very real support among the Menghean population. This is especially true in rural areas, and among freshly minted members of the emerging middle class. Remarking on the durability of Choe's support, political scientist Robert Immelman noted that "[a]ny Menghean citizen born long enough before 1987 to have experienced the hardship, shortages, and turmoil of this period would have seen an almost incomprehensible change in the national economy during their lifetime, with the divergence taking place soon after Choe Sŭng-min came to power... it is hard to exaggerate the impact which this transformation had on people's views of the new leadership, and the extent to which belief in the 'Choe myth' has survived to the present." | While foreign intellectuals have generally derided Choe's personality cult as exaggerated and blatantly propagandized, it has gained very real support among the Menghean population. This is especially true in rural areas, and among freshly minted members of the emerging middle class. Remarking on the durability of Choe's support, political scientist Robert Immelman noted that "[a]ny Menghean citizen born long enough before 1987 to have experienced the hardship, shortages, and turmoil of this period would have seen an almost incomprehensible change in the national economy during their lifetime, with the divergence taking place soon after Choe Sŭng-min came to power... it is hard to exaggerate the impact which this transformation had on people's views of the new leadership, and the extent to which belief in the 'Choe myth' has survived to the present." | ||

=== | ===Return to power-sharing=== | ||

On July 14th, 2002, a group of high-ranking officials met with Choe Sŭng-min in private to confront him about the excesses of the [[Disciplined Society Campaign]]. In the "July discussion" that followed, Choe initially accused his counterparts of refusing to comply with a central intiative, but he was unwilling to threaten arrest and dismissal against a group that included some of his most trusted advisors and subordinates. In the end, he conceded to them that the strictly enforced campaign was having counterproductive results, and agreed to let them scale it back. | On July 14th, 2002, a group of high-ranking officials met with Choe Sŭng-min in private to confront him about the excesses of the [[Disciplined Society Campaign]]. In the "July discussion" that followed, Choe initially accused his counterparts of refusing to comply with a central intiative, but he was unwilling to threaten arrest and dismissal against a group that included some of his most trusted advisors and subordinates. In the end, he conceded to them that the strictly enforced campaign was having counterproductive results, and agreed to let them scale it back. | ||

At the Fourth Party Congress in 2003, Choe Sŭng-min announced an end to the Disciplined Society Campaign, under the covering excuse that it had succeeded in reshaping popular morals "at the foundational but not the superficial level." In a more open bow to his inner circle, he also introduced the "three ups and three downs" (''samsang samha'') principle. According to this principle, ideas and proposals from the general population would filter up to the Party staff, then to the central administrative organs, and finally to the Supreme Council, which would deliberate on them and formulate policy while taking them into account; after making a decision, the Supreme Council would pass this down to the central administrative organs, the Party staff, and the general population for implementation. Choe framed this approach as a core component of "Menghean-style democracy" (''Mengguk-tŭksaek minjujuyi''), which combined the respective strengths of centralized authority, technocratic specialization, and popular input. | At the Fourth Party Congress in 2003, Choe Sŭng-min announced an end to the Disciplined Society Campaign, under the covering excuse that it had succeeded in reshaping popular morals "at the foundational but not the superficial level." In a more open bow to his inner circle, he also introduced the "three ups and three downs" (''samsang samha'') principle. According to this principle, ideas and proposals from the general population would filter up to the Party staff, then to the central administrative organs, and finally to the Supreme Council, which would deliberate on them and formulate policy while taking them into account; after making a decision, the Supreme Council would pass this down to the central administrative organs, the Party staff, and the general population for implementation. Choe framed this approach as a core component of "Menghean-style democracy" (''Mengguk-tŭksaek minjujuyi''), which combined the respective strengths of centralized authority, technocratic specialization, and popular input. | ||

Another marked retreat on Choe's part followed Menghe's disastrous involvement in the [[Ummayan Civil War]], which brought it to the brink of open conflict with neighboring [[Maverica]] and [[Innominada]] and brought little in the way of strategic advantage. Choe's first response was to order deep-reaching reforms of the military's command structure and offensive {{wp|military doctrine|doctrine}} with the aim of creating a more competent fighting force. In the process, he delegated extensive authority to Marshal Jŏng Tae-ho, the Supreme Commander of the Army, and High Admiral Wu Hyŏng-jun, the Supreme Commander of the Navy, both recent appointments who had previously won renown for their doctrinal writings and planning work. The resulting 2005 military reforms set the Menghean armed forces on the path to improvement, but at a cost to Choe's authority: both Jŏng and Wu took deliberate steps to edge the Supreme Commander's influence out of their respective branches, believing that excessive political interference was one of the reasons the Menghean military had performed poorly in previous years. Choe Sŭng-min had little choice but to comply with their resistance, as the Maverican and Innominadan military threats demanded a competent force. | Another marked retreat on Choe's part followed Menghe's disastrous involvement in the [[Ummayan Civil War]], which brought it to the brink of open conflict with neighboring [[Maverica]] and [[Innominada]] and brought little in the way of strategic advantage. Choe's first response was to order deep-reaching reforms of the military's command structure and offensive {{wp|military doctrine|doctrine}} with the aim of creating a more competent fighting force. In the process, he delegated extensive authority to Marshal Jŏng Tae-ho, the Supreme Commander of the Army, and High Admiral Wu Hyŏng-jun, the Supreme Commander of the Navy, both recent appointments who had previously won renown for their doctrinal writings and planning work. The resulting [[2005 Menghean military reforms|2005 military reforms]] set the Menghean armed forces on the path to improvement, but at a cost to Choe's authority: both Jŏng and Wu took deliberate steps to edge the Supreme Commander's influence out of their respective branches, believing that excessive political interference was one of the reasons the Menghean military had performed poorly in previous years. Choe Sŭng-min had little choice but to comply with their resistance, as the Maverican and Innominadan military threats demanded a competent force. | ||

Consistent with these trends, the 2008 Fifth Party Congress saw a further embrace of "Menghean-style democracy;" the words "consensus," "harmony," and "collective (leadership, governance, etc)" appeared more frequently in Choe's opening speech here than in any of his other Party Congress events. The Fifth Party Congress also included longer speeches by other leading officials, including Kim Pyŏng-so, the recently-appointed Vice-Secretary of the Party. Increased attention to Kim at and after the event, as well as his ascent to two high-ranking posts, led many observers to identify him as Choe's presumed successor, a marked contrast to Choe Sŭng-min's earlier practice of preventing any single official from being able to claim second-in-command status. | Consistent with these trends, the 2008 Fifth Party Congress saw a further embrace of "Menghean-style democracy;" the words "consensus," "harmony," and "collective (leadership, governance, etc)" appeared more frequently in Choe's opening speech here than in any of his other Party Congress events. The Fifth Party Congress also included longer speeches by other leading officials, including [[Kim Pyŏng-so]], the recently-appointed Vice-Secretary of the Party. Increased attention to Kim at and after the event, as well as his ascent to two high-ranking posts, led many observers to identify him as Choe's presumed successor, a marked contrast to Choe Sŭng-min's earlier practice of preventing any single official from being able to claim second-in-command status. | ||

Analysts and observers have disagreed on the extent to which the events between 2002 and 2008 brought about a genuine reduction in Choe's political power. Amelia Dunn claims that by the end of the Fifth Party Congress, Menghe had returned to a status of "contested autocracy," in which Choe was no longer able to make important decisions without the approval of other key elites. A similar theory portrays an ongoing transition toward institutionalized decision-making, in which formal rules and procedures serve as constraints on both Choe and the other members of his inner circle. Prominent political scientist Victor Kowalski disagrees, instead asserting that "Choe Sŭng-min's power is now sufficiently entrenched that he can comfortably delegate tasks, solicit input, and strengthen the [[Menghean Socialist Party|MSP]]'s institutional structure without fearing that rival cliques will perceive this as weakness and edge him off the throne. There are, quite simply, no rival cliques capable of contesting his authority in any meaningful way." | Analysts and observers have disagreed on the extent to which the events between 2002 and 2008 brought about a genuine reduction in Choe's political power. Amelia Dunn claims that by the end of the Fifth Party Congress, Menghe had returned to a status of "contested autocracy," in which Choe was no longer able to make important decisions without the approval of other key elites. A similar theory portrays an ongoing transition toward institutionalized decision-making, in which formal rules and procedures serve as constraints on both Choe and the other members of his inner circle. Prominent political scientist Victor Kowalski disagrees, instead asserting that "Choe Sŭng-min's power is now [in 2010] sufficiently entrenched that he can comfortably delegate tasks, solicit input, and strengthen the [[Menghean Socialist Party|MSP]]'s institutional structure without fearing that rival cliques will perceive this as weakness and edge him off the throne. There are, quite simply, no rival cliques capable of contesting his authority in any meaningful way." | ||

=== | ===Health issues and waning power=== | ||

In the early 2010s, while he was in his mid-seventies, Choe Sŭng-min began to suffer from a variety of health issues. He briefly disappeared from public view in March-April 2012 and again in June 2014, but neither of these disappearances received any state media attention, with official government spokespeople explaining that the Chairman was busy taking care of state issues. In late August 2017, however, he disappeared for close to a month, fueling speculation too large to ignore. Opposition media outlets in [[Altagracia]] claimed that he had died, and some foreign think tanks theorized that he may have been sidelined by a group of his advisors. Eventually, Choe made an unusual appearance on September 17th, holding a televised interview with the state-run ''Jung'ang Ilbo'' while reclining in a hospital bed at the Bŏdŭl-ri Medical Center in Hyangchun. He continued to rule from Bŏdŭl-ri for a month and a half, returning to Donggyŏng on November 4th. | |||

During this period, state media reported that the Chairman was experiencing medical issues related to his heart and chest, but official reports consistently described the problem in vague and general terms. The symptoms described in these reports are consistent with some form of {{wp|angina}}, though the root cause remains unclear; Choe Sŭng-min was never a smoker, he gave up drinking in the mid-90s, and he was not overweight. As the months passed, official propaganda shifted from dismissing Choe Sŭng-min's illness to praising it, explaining, again in vague terms, that the Chairman's health problems were a result of "thirty years of stressful days and sleepless nights tirelessly managing all national affairs." | |||

Minor, brief disappearances continued until 5 January 2019, when state media announced that Choe Sŭng-min had slipped and fallen while descending a flight of stairs in Donggwangsan and was undergoing emergency treatment. He ultimately survived this accident, but never made a full recovery. In the two years that followed, he almost always walked with a cane, and sometimes relied on other top leaders to support him while walking longer distances. Already relatively thin, he lost a significant amount of weight, becoming gaunt and frail. For most of 2019 and early 2020, he avoided any appearance of weakness in public, but during the second half of 2020 he made a number of domestic and foreign media appearances in a wheelchair. | |||

== | Choe's worsening health set off a quiet power struggle in the top ranks of the Menghean government. From 1994 onward, Choe Sŭng-min had concurrently held all of Menghe's three top government positions, and on multiple occasions he had purged possible successors, leaving the [[Menghean Socialist Party]] thoroughly unprepared to handle a stable succession. [[Kim Pyŏng-so]], his successor-in-waiting since 2008, was only slightly younger than the incumbent Chairman and famous mainly for being unremarkable and agreeable. [[Mun Chang-ho]], a veteran economic policymaker, made a flurry of public appearances during Choe's 2017 hospitalization, positioning himself as a plausible competitor. Choe tacitly endorsed this unprecedented move, and at the 7th Party Congress in 2018 he elevated Mun Chang-ho to the rank of Vice Secretary of the MSP. Subsequently, he encouraged Mun and Kim to rule as partners during his periods of hospitalization, apparently believing that he could improve both men's performance by creating some degree of competition. This did not sit well with [[Kang Yong-nam]], the Supreme Commander of the Menghean Army, who saw Mun Chang-ho as overly liberal. Choe Sŭng-min did not promote Kang to any civilian political posts in the 2018-2019 government turnover, but he did not discipline Kang either, possibly because he did not appreciate the extent of Kang's aspiration for power and possibly because he was afraid to cause any instability. | ||

{{main|Death and state funeral of Choe Sŭng-min}} | |||

Choe Sŭng-min suffered a heart attack on the evening of 12 February 2021, and was subsequently rushed to Sinsuk Central Hospital for treatment. There, medical staff were able to stabilize his condition somewhat, but he did not regain consciousness and his condition rapidly worsened. He was pronounced dead at 11:52 PM on February 17th. In a ceremony apparently planned long in advance, Choe's body {{wp|Lying in state|lay in state}} in a glass coffin on Heroes' Square for ten days while ordinary citizens and government officials filed past to make offerings and pay their respects. On February 17th, his body was transported to the Sudŏk Temple for cremation, in accordance with [[Chŏndoism|Chŏndo]] religious tradition. | |||

==Policy and ideology== | |||

===Economic policy=== | ===Economic policy=== | ||

Choe Sŭng-min's economic policies are difficult to classify on the conventional {{wp|Left–right_political_spectrum|right-left spectrum}}. The core imperative of his time in power was | Choe Sŭng-min's economic policies are difficult to classify on the conventional {{wp|Left–right_political_spectrum|right-left spectrum}}. The core imperative of his time in power was {{wp|economic development}} - epitomized in such slogans as "build up the economy" (''gyŏngje-ŭl jŭngganghae'') and "enrich the country, strengthen the military" (''[[Choe_Sŭng-min_Thought#Buguk_Gangby.C5.8Fng|buguk gangbyŏng]]''). In the 1990s and 2000s, this grew into an approach some foreign scholars termed {{wp|Gross_domestic_product|GDP}}-ism," in which government officials were rewarded and promoted based primarily on their ability to generate economic growth. | ||

Given that Menghe entered the late 1980s as a {{wp|Socialism|socialist}} state with a {{wp|planned economy}}, Choe's [[Economic | Given that Menghe entered the late 1980s as a {{wp|Socialism|socialist}} state with a {{wp|planned economy}}, Choe's [[Economic reform in Menghe|economic reforms]] involved a relative shift toward {{wp|Economic_liberalization|economic liberalization}}: allowing {{wp|Market_(economics)|markets}} to naturally determine prices, converting {{wp|state-owned enterprise}}s into semi-private [[Jachi-hoesa]], and [[Agriculture_in_Menghe#Agricultural_reforms|decollectivizing agriculture]]. Choe also oversaw and defended a campaign to roll back "{{wp|Work_unit|work unit}} socialism," dissolving job security and welfare benefits for hundreds of millions of workers, and outlawed the formation of independent {{wp|Trade_union|labor unions}}. | ||

At the same time, however, Choe Sŭng-min opposed {{wp|Laissez-faire|laissez-faire}} economics in his personal writings and official policymaking, and insisted on maintaining a {{wp|Dirigisme|dirigiste}} role for the state in the new economic order. He regularly invoked military discipline and [[Choe_Sŭng-min_Thought#Selflessness|selfless austerity]] to criticize excessive displays of material wealth among the emerging elite, especially during the 1990s and 2000s, and in 2015 he pushed through [[Taxation_in_Menghe|comprehensive tax reform]] which imposed a heavily {{wp|Progressive_tax|progressive}} {{wp|Income_tax|income tax}} and a 40% {{wp|Inheritance_tax|inheritance tax}} on large estates. | At the same time, however, Choe Sŭng-min opposed {{wp|Laissez-faire|laissez-faire}} economics in his personal writings and official policymaking, and insisted on maintaining a {{wp|Dirigisme|dirigiste}} role for the state in the new economic order. He regularly invoked military discipline and [[Choe_Sŭng-min_Thought#Selflessness|selfless austerity]] to criticize excessive displays of material wealth among the emerging elite, especially during the 1990s and 2000s, and in 2015 he pushed through [[Taxation_in_Menghe|comprehensive tax reform]] which imposed a heavily {{wp|Progressive_tax|progressive}} {{wp|Income_tax|income tax}} and a 40% {{wp|Inheritance_tax|inheritance tax}} on large estates. | ||

Many scholars of {{wp|Comparative_politics|comparative politics}} have identified Choe's economic order as a quintessential {{wp|Developmental_state|developmental state}} or developmental dictatorship, in which strong but indirect state control over the economy is used to mobilize the whole society for economic growth. A few have even suggested that the Menghean term ''Sahoejuyi'' (사회주의 / 社會主義), as used by Choe Sŭng-min and the [[Menghean Socialist Party]], is better translated through its literal meaning of "society-ism," a {{wp|corporatism|corporatist}} ideology in which all social classes must cooperate for the well-being of the nation. Critics of the Menghean regime, especially those in [[Maverica]], contend that Choe's economic ideology is a disguised form of {{wp|Fascism|fascism}} or "national | Many scholars of {{wp|Comparative_politics|comparative politics}} have identified Choe's economic order as a quintessential {{wp|Developmental_state|developmental state}} or developmental dictatorship, in which strong but indirect state control over the economy is used to mobilize the whole society for economic growth. A few have even suggested that the Menghean term ''Sahoejuyi'' (사회주의 / 社會主義), as used by Choe Sŭng-min and the [[Menghean Socialist Party]], is better translated through its literal meaning of "society-ism," a {{wp|corporatism|corporatist}} ideology in which all social classes must cooperate for the well-being of the nation. Critics of the Menghean regime, especially those in [[Maverica]], contend that Choe's economic ideology is a disguised form of {{wp|Fascism|fascism}} or "national socialism," in which production is organized for the benefit of the {{wp|Nation_state|nation-state}} or even the [[Meng]] ethnicity. | ||

===Nationalism=== | ===Nationalism=== | ||

Few among Choe Sŭng-min's supporters and detractors would contest that he was an ardent {{wp|Nationalism|nationalist}}, a trait strongly influenced by his service in the War of Liberation and his time in the National Defense Academy. Indeed, his economic policy was strongly informed by a sense, shared by many of his contemporaries, that Menghe had fallen behind its rightful place as the hegemonic power of the Eastern Hemisphere and needed to expand its economy and military in order to restore the geopolitical balance that had existed before [[Menghean Black Plague|1508]]. In speeches and writings, Choe referred to this project as the [[Choe_Sŭng-min_Thought#The_Path_of_National_Reconstruction|Path of National Reconstruction]]. | Few among Choe Sŭng-min's supporters and detractors would contest that he was an ardent {{wp|Nationalism|nationalist}}, a trait strongly influenced by his service in the War of Liberation and his time in the National Defense Academy. Indeed, his economic policy was strongly informed by a sense, shared by many of his contemporaries, that Menghe had fallen behind its rightful place as the hegemonic power of the Eastern Hemisphere and needed to expand its economy and military in order to restore the geopolitical balance that had existed before [[Menghean Black Plague|1508]]. In speeches and writings, Choe referred to this project as the [[Choe_Sŭng-min_Thought#The_Path_of_National_Reconstruction|Path of National Reconstruction]]. | ||

There is greater disagreement on the degree of continuity between Choe Sŭng-min and earlier Menghean nationalist leaders [[Kim Myŏng-hwan]] and [[Kwon Chong-hoon]]. Under veteran Army officers in the National Defense Academy, Choe was undoubtedly trained in the attitudes of the former Imperial Menghean Army, and many in his generation felt deep humiliation and resentment over Menghe's defeat in the [[Pan-Septentrion War]]. Some of Choe's former MNDA | There is greater disagreement on the degree of continuity between Choe Sŭng-min and earlier Menghean nationalist leaders like [[Kim Myŏng-hwan]] and [[Kwon Chong-hoon]]. Under veteran Army officers in the National Defense Academy, Choe was undoubtedly trained in the attitudes of the former Imperial Menghean Army, and many in his generation felt deep humiliation and resentment over Menghe's defeat in the [[Pan-Septentrion War]]. Some of Choe's former MNDA 1 classmates, speaking anonymously in recent years, have asserted that he showed a strong attachment to the [[Greater Menghean Empire]] and its former leaders, including Kwon Chong-hoon, who is currently portrayed somewhat negatively in official Menghean accounts of the war. | ||

In contrast to General Kwon, however, Choe promoted a peaceful (if still militarized) approach to reconstruction, characterized by a long-term focus on development. In his first diplomatic meeting with foreign leaders, he reassured the world that Menghe did not and would not lay claim to any territory beyond its existing borders, with the notable exception of [[Altagracia]]. Choe Sŭng-min has also repeatedly stressed that national restoration is first and foremost an economic project, and that he would not embark on the same kind of aggressive expansionism which Kwon and Kim had favored - a promise which did not stop him from intervening in Innominada during its [[Innominadan Crisis|political crisis]]. | |||

Choe also formally declared his opposition to {{wp|Supremacism|racial supremacism}}, including claims that the [[Meng]] are ethnically superior or that they deserve a privileged role in Menghean governance. After Menghe entered the [[Ummayan Civil War]] and experienced a resurgence in [[Lac people|Lakkian]] and [[Argentans|Argentan]] secessionism, he also ordered blanket censorship of {{wp|Islamophobia|Shahidophobic}} speech, or any other expression which "seeks to undermine pan-ethnic brotherhood." Nevertheless, many critics contend that Menghean cultural supremacy and anti-Western biases remain prominent subtexts in Choe's rhetoric, never openly stated but frequently implicit. | |||

===Foreign relations=== | |||

Choe Sŭng-min's approach to foreign relations was surprisingly pragmatic in light of his childhood and upbringing. His early writings, especially the Suk Su-dŏk pamphlets, show strong anti-foreign sentiment reminiscent of the [[Greater Menghean Empire]], including outspoken support for the Empire and its policies. Upon actually coming to power, however, Choe realized that Menghe would have to repair its relations with the rest of the world in order to stabilize its ailing economy and secure access to famine relief. He promptly announced plans to dismantle Menghe's nuclear weapons stockpile in return for humanitarian aid, and after establishing the Socialist Republic of Menghe, he opened embassies with [[Dayashina]], Banbha, Hallia, and Anglia and Lechernt, among others. | |||

Choe's most pragmatic foreign policy move was a 2001 memorandum in which he relinquished Menghe's claim to the [[Renkaku Islands]], which had been owned and occupied by Dayashina for the last several centuries. Though controversial with many Menghean nationalists, this move allowed Menghe to strengthen ties with Dayashina and its allies, even securing permission to import foreign arms. In the decade that followed, Choe Sŭng-min played an active role in re-aligning Menghe away from its old socialist allies and toward Hallia, Dayashina, and Banbha. In the last years of his life, he actively strove to organize a tripartite alliance between Dayashina, Banbha, and Menghe, but the three countries were only able to agree on bilateral defense cooperation. | |||

During the same period, Menghe experienced a worsening of relations with [[Maverica]], [[Innominada]], and the [[Entente Cordiale]], nearly escalating to a large-scale conflict over the [[Ummayan Civil War]]. Though largely forgiving, or at least passing over, the historical imperialist projects of his newfound allies, Choe Sŭng-min redirected his anti-imperialist fervor against the Entente Cordiale, deriding it as a thinly veiled front to maintain Casaterran civilizational supremacy in the Eastern Hemisphere. He was especially hostile toward Anglia and Lechernt, as his mother and many of his comrades-in-arms had been killed by Anglian soldiers during the War of Liberation. Choe Sŭng-min was also personally distrustful of labor-centric socialist movements, including the ones that held power in Maverica, Innominada, and the Allied Nations of Maracaibo, comparing them to Ryŏ Ho-jun's misrule in the DPRM. | |||

Choe | Among smaller countries, Choe advanced a rhetoric of anti-imperialism and mutual cooperation, transforming [[International United Front for Opposing Imperialism|IUFOI]] from an arms shipment and advisory body for anti-colonial movements into a far-reaching organization for promoting Menghean soft power. His diplomatic strategy toward the continent of Meridia centered on building ties with the country's indigenous-run states while supporting opposition movements in its apartheid states and neocolonial puppet regimes, in the hopes that these states would tip toward Menghe after regime change. Choe backed up this rhetoric with periodic state visits and offers of lucrative infrastructure spending, including the [[Northern Road and Southern Circuit]] initiative, which would turn Menghe into a key trading nexus in the Eastern hemisphere. | ||

==Personal life== | ==Personal life== | ||

While Menghean state media and educational propaganda reported extensively on Choe Sŭng-min's public activities, little specific information is known about his personal life, which he firmly kept out of the spotlight. | |||

True to his pledge, Choe Sŭng-min did not remarry after Cho In-hye's death, instead remaining single up until his own death in 2021. Consequently, he had no children. This fact may have shielded him somewhat from allegations of {{wp|nepotism}} and favoritism, which dogged other top figures in the MSP during the 2010s and 2020s, thereby upholding his public image as selfless and incorruptible. State propaganda attribute this lifestyle to Choe's devotion to political affairs, often referencing a 1993 quote in which he explained that he would rather devote his full time and energy to becoming a father figure for the entire nation, but Choe's real motives for not remarrying remain unclear. | |||

Choe Sŭng-min also made no public visits to his extended family during his time in office, a similarly unusual omission given the emphasis on family in [[Meng]] customs. Both his parents are known to have died before 1964, and he had no siblings, but he is known to have cousins on his father's side. Official news media have never directly commented on this side of Choe Sŭng-min's family, and even the names of his relatives are unknown; Choe is one of the most common surnames in southern Menghe, making independent verification of his family line difficult. To date, the only public appearance of any of Choe Sŭng-min's relatives occurred [[Death_and_state_funeral_of_Choe_Sŭng-min#Funeral_and_cremation|at his funeral]], when four unknown individuals, believed to be a cousin's descendants, proceeded past his glass coffin immediately after a group of top officials. Some experts speculate that Choe was unwilling to share the spotlight out of a fear that someone else in his family might vie for power or humiliate him; others group it alongside his single status as part of an effort to cultivate an image as the full-time father of the nation. In any case, this relative isolation helped bolster Choe Sŭng-min against allegations of nepotism, and the policy against reporting on Choe's family appears to have continued after his death. | |||

In his own personal living arrangements, Choe Sŭng-min cultivated an image of military asceticism, both out of preference and as part of his personality cult. He never took up smoking, despite its popularity in top military and Party circles in the 1970s and 1980s, and he gave up drinking in 1996 as part of the [[Disciplined Society Campaign]]. Though he lived in the [[Donggwangsan]] Palace for most of his time as Chairman of the Supreme Council, on most nights he slept in the servant's room in the northeast corner of the building, rather than the master bedroom on the floor below. | |||

Throughout his entire time in office, Choe Sŭng-min never appeared in public in a {{wp|Suit|Western business suit}}, instead wearing a military uniform or {{wp|Mao_suit|sinmengsam}}. From the early 1990s onward, he typically wore a gray or black uniform to signify his status as the combined commander of the Army and Navy, rather than a commander of the Army alone. | |||

==Titles and terms of address== | ==Titles and terms of address== | ||

[[Menghean language|Menghean]] is a language which gives great importance to {{wp|Korean honorifics|honorifics}} when addressing a social superior. As such, any time Choe Sŭng-min | [[Menghean language|Menghean]] is a language which gives great importance to {{wp|Korean honorifics|honorifics}} when addressing a social superior. As such, any time Choe Sŭng-min was addressed directly, his name must be followed by the suffix ''gak'ha'' (각하 / 閣下), equivalent to the Themiclesian ''klak-ghra’'' and the Dayashinese ''kakka''. ''Gak'ha'' may also be used by itself in address. In {{wp|English language|Anglian}}, ''gak'ha'' is usually translated to "His Excellency," which conveys roughly the same rank of respect. Thus in foreign policy documents and diplomatic meetings, the proper Anglian term of address would be "His Excellency Choe Sŭng-min," or "Your Excellency" in direct address. | ||

When referred to in the third person, Choe's surname or full name | When referred to in the third person, Choe's surname or full name was almost always followed by one of his titles (e.g., ''Choe Sŭng-min (dae)wŏnsu'', "(Supreme) Marshal Choe Sŭng-min") or (''Choe yijang'', "Chairman Choe"). When such titles were used in isolation, they generally received the formal suffix -''nim'', i.e. ''(dae)wŏnsunim'', ''yijangnim''. ''Choe Sŭng-min dongji'' ("Comrade Choe Sŭng-min") has appeared in some contexts, most notably patriotic songs and propaganda posters, but in general "comrade" is considered an insufficiently formal term of address and it is not used in news announcements or official documents. "Marshal" was his most widely used title from 1993 to the mid-2000s, after which "Chairman" once again became dominant; he has held both posts continuously and concurrently since 1988. | ||

A 2007 foreign book ''The Choe Sŭng-min Personality Cult'' enumerated the following list of titles and {{wp|epithet}}s which had been used over the previous twenty years: | A 2007 foreign book ''The Choe Sŭng-min Personality Cult'' enumerated the following list of titles and {{wp|epithet}}s which had been used over the previous twenty years: | ||

* ''Choego | * ''Choego Saryŏnggwan'' (Supreme Commander) | ||

* ''Choego Suryŏngnim'' (Supreme Leader) | * ''Choego Suryŏngnim'' (Supreme Leader) | ||

* ''Danggwa Jŏngbuwa Gundae-e Suryŏngnim'' (Leader of the Party, State, and Army) | * ''Danggwa Jŏngbuwa Gundae-e Suryŏngnim'' (Leader of the Party, State, and Army) | ||

| Line 196: | Line 225: | ||

* ''Chinaehanŭn Yijangnim'' (Dear Chairman) | * ''Chinaehanŭn Yijangnim'' (Dear Chairman) | ||

* ''Bulsechul-e Suryŏngnim'' (Unparalleled Leader) | * ''Bulsechul-e Suryŏngnim'' (Unparalleled Leader) | ||

* '' | * ''Gukga Gyŏngje Gijog-e Sangjing'' (Symbol of the [[Menghean economic miracle|National Economic Miracle]]) | ||

* ''Jongyŏnghanŭn Yijangjim'' (Respected Chairman) | * ''Jongyŏnghanŭn Yijangjim'' (Respected Chairman) | ||

* ''On Nara-e Hyangdosŏng'' (Guiding Star of the Whole Nation) | * ''On Nara-e Hyangdosŏng'' (Guiding Star of the Whole Nation) | ||

| Line 207: | Line 236: | ||

* ''Midŏg-e Gwigam'' (Paragon of Virtue) | * ''Midŏg-e Gwigam'' (Paragon of Virtue) | ||

== | ==Awards and decorations== | ||

==Legacy== | |||

Choe Sŭng-min held power for just shy of 34 years, starting with his self-coup on 1 March 1988 and ending with his death on 17 February 2021. On the eve of his death, he was one of Septentrion's longest-serving heads of state, excluding ceremonial monarchs. Even after his death, he remains one of the longest-serving non-monarchical rulers of the 20th century. During his time in office, Menghe grew from a mostly rural impoverished country to a middle-income economy, even surpassing Banbha to become the largest economy in Septentrion by GDP. Economic growth also allowed Menghe to sustain the world's largest military budget and the largest military by number of active personnel. His early rule was characterized by an extreme concentration of power, especially in the 1990s, but over the course of the 2000s and 2010s he oversaw a partial political thaw. | |||

In Menghe, Choe Sŭng-min is overwhelmingly seen favorably, celebrated most often for his role in orchestrating the [[Menghean economic miracle]] and transforming Menghe into the world's strongest military and economic power. Under his rule, real (inflation and PPP-adjusted) GDP per capita rose tenfold, from $3,390 in 1987 to $37,773 in 2021. Economic estimates credit him with lifting over 300 million people out of dollar-a-day poverty, more than any other ruler in human history. As such, Choe is especially popular among older generations who experienced the hardship of the occupation era and the recurrent famines of the DPRM only to see their surroundings entirely transformed under Choe's leadership. Nationalist education and state propaganda have also intensified Menghean support for Choe, who is widely regarded as the founding father of the current Menghean state. Choe Sŭng-min's death appears to have elevated the late Chairman's status even further, in part by severing his ties to the problems of the current leadership. An independent survey conducted in 2021 found that Menghean citizens overwhelmingly selected Choe Sŭng-min as the greatest Menghean leader in modern history, though most of the competitors on that list were autocrats as well. | |||

Critics of Choe Sŭng-min, both in Menghe and abroad, regard him as a repressive dictator who promised liberalization upon coming to power but instead delivered an iron-fisted personality cult. He staunchly opposed free speech and free elections throughout his time in office, and he criticized the [[Elections_in_Menghe#2019_National_Assembly_elections|2019 National Assembly elections]], in which independent candidates were allowed to run for the first time. During his rule, the [[Internal Security Forces (Menghe)|Internal Security Forces]] and [[Internal Intelligence Agency (Menghe)|Internal Intelligence Agency]] detained untold numbers of dissidents and constructed a high-tech system of surveillance and censorship. Younger generations in Menghe, especially those born after Choe came to power, tend to be more critical of his role in blocking democratization, though young nationalists identify him with the country's return to world prominence. | |||