Tamara Łempicka: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

She lived a lavish, bohemian, and hedonistic lifestyle, which completed her fame. She bought a Bugatti racing car to live up to her self-portrait, worked in a luxurious apartment and studio in Senik designed by her sister, and owned a mansion in Valona, where she entertained extravagantly. | She lived a lavish, bohemian, and hedonistic lifestyle, which completed her fame. She bought a Bugatti racing car to live up to her self-portrait, worked in a luxurious apartment and studio in Senik designed by her sister, and owned a mansion in Valona, where she entertained extravagantly. | ||

Although she and Tadeusz drifted apart to an extent, they remained married and turned their relationship into an {{wpl|open marriage}}. Renowned for her libido, Tamara was {{wpl|bisexual}} and had a string of affairs, including a notorious one with [[Emilia Malandrino]]; she took mischievous delight in recounting that Emilia was more submissive in the bedroom than her public image. She became closely associated with prominent lesbian and bisexual women in Alscia's artistic circles, which included [[Adela Stein]]. | Although she and Tadeusz drifted apart to an extent, they remained married and turned their relationship into an {{wpl|open marriage}}. Renowned for her libido, Tamara was {{wpl|bisexual}} and had a string of affairs, including a notorious one with [[Emilia Malandrino]]; she took mischievous delight in recounting that Emilia was more submissive in the bedroom than her public image. | ||

She became closely associated with prominent lesbian and bisexual women in Alscia's artistic circles, which included [[Adela Stein]]. | |||

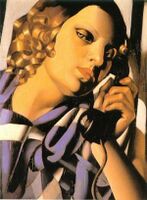

[[File:TamaraŁempicka-2.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Tamara's public image famously used aloofness to create sexual appeal]] | [[File:TamaraŁempicka-2.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Tamara's public image famously used aloofness to create sexual appeal]] | ||

| Line 72: | Line 74: | ||

Tamara was an ardent, lifelong opponent of {{wpl|Futurism#1920s and 1930s|Political Futurism}}. Although in private she was scathing about futurism as an artistic movement, she was a member and president of the [[Anarchofuturist Association of Alscia]], as she felt it was vital that Alscia's artists form a {{wpl|united front}} with leftists to reclaim futurism from the Megelanese and [[Æsthurlavaj|Æsthurlav]] regimes. | Tamara was an ardent, lifelong opponent of {{wpl|Futurism#1920s and 1930s|Political Futurism}}. Although in private she was scathing about futurism as an artistic movement, she was a member and president of the [[Anarchofuturist Association of Alscia]], as she felt it was vital that Alscia's artists form a {{wpl|united front}} with leftists to reclaim futurism from the Megelanese and [[Æsthurlavaj|Æsthurlav]] regimes. | ||

She was a strong supporter of the [[Free Megelanese]] community. She turned down offers to run for the [[Alscia#Legislative Council|Legislative Council]], but was elected mayor of Valona | She was a strong supporter of the [[Free Megelanese]] community. She turned down offers to run for the [[Alscia#Legislative Council|Legislative Council]], but was elected mayor of Valona in [[List of Alscian local elections#1930|1930]] and [[List of Alscian local elections#1932|1932]]. Her first election campaign used posters of ''Autoportrait'' emblazoned with the word ''SINDACA'' ("mayor"). In her victory speech, she paraphrased ''Risveglio Nazionale'', declaring, ''Cette femme est maire!'' ("This woman is a mayor!"). | ||

She took a mainly ceremonial role as mayor, leaving the ''giunta comunale'' to handle day-to-day governance, and focused on supporting the city's arts and nightlife. Although conceding she was best suited for a limited role, she took her mayoral duties seriously, and sought mainly to serve as a symbol of pride for residents, that they could boast the "baroness with a brush" as their mayor. She portrayed her terms as an advance for [[Alscia#Direct democracy|direct democracy]] in the city. | She took a mainly ceremonial role as mayor, leaving the ''giunta comunale'' to handle day-to-day governance, and focused on supporting the city's arts and nightlife. Although conceding she was best suited for a limited role, she took her mayoral duties seriously, and sought mainly to serve as a symbol of pride for residents, that they could boast the "baroness with a brush" as their mayor. She portrayed her terms as an advance for [[Alscia#Direct democracy|direct democracy]] in the city. | ||

Revision as of 17:19, 3 January 2020

Tamara Łempicka | |

|---|---|

Tamara Łempicka, 1933 | |

| Born | Maria Tamara Górska 16 May 1898 Toruń, Shalum |

| Died | 18 March 1980 (aged 81) Alba, Megelan |

| Nationality | |

| Style | Art Deco |

| Spouse(s) | Tadeusz Łempicki |

| Children | Kizette Łempicka |

| Relatives | Adriana Górska (sister) |

Tamara Łempicka (Gylic transcription: Tamara Uémpiţka; 16 May 1898 – 18 March 1980) was a Megelanese–Gylian painter, art patron, collector, and socialite. Born in Shalum, she spent the majority of her life in Megelan, Alscia, the Free Territories, and Gylias, and was mainly associated with them.

Tamara's distinctive style came from a fusion of neoclassical discipline and cubist modernism. She was the leading exponent of Art Deco in Alscia, and gained renown in Tyran. At the height of her fame in the 1920s–1930s, she was known for her glamorous portraits of high society and highly stylised paintings of nudes.

Nicknamed the "baroness with a brush", Tamara's hedonistic private life and intense love affairs aroused scandal and bolstered her fame. She was a prominent member of the Megelanese and Alscian artistic scenes, and was politically active in both countries, serving variously as a member of the Credenza, president of the Anarchofuturist Association of Alscia, and mayor of Valona.

Although Tamara's style fell out of favour regionally in the 1940s, she had an immense impact on the development of Gylian art. She retained a strong following during the Free Territories and mentored artists, and was a fundamental influence on gauchic. Her career benefited from a resurgence in interest in Art Deco in the late 1960s, but by this time her style had become more abstract. She died in Megelan in 1980.

Early life

She was born Maria Tamara Górska on 16 May 1898 in Toruń, Shalum. She came from a wealthy family: her father was an attorney for a trading company and her mother was a socialite. She was the second of three children; her sister Adriana Górska was born a year later.

When she was ten, her mother commissioned a pastel portrait of her by a prominent local artist. She detested posing and was dissatisfied with the finished work. She took the pastels, posed Adriana, and made her first portrait.

She attended boarding school, but she was listless and feigned illness to leave. Instead, she accompanied her grandmother on a tour of Akashi and Cacerta, where she developed her interest in art.

Restless and increasingly distant from her parents, she spent time with other relatives instead. Aged 15, she fell in love with Tadeusz Łempicki — "a well-known ladies man, gadabout, and lawyer by title", according to a biographer. They married on her 18th birthday.

She changed her name on marriage to "Tamara Łempicka". She remained known as "Maria" among close family such as her sister.

Career

Tamara and Adriana moved to Megelan, where they followed their artistic pursuits. She was encouraged by Adriana to become a painter; boredom with her marriage and the birth of her daughter provided additional incentives.

The sisters moved to Alscia to escape the 1919–45 civil war and rise of the Futurist Political Party. Adriana became an architect, while Tamara sold and exhibited her first paintings in 1922.

She had her breakthrough in 1925, when she exhibited her paintings at the Cacertian Empire international exhibition in Cesena. This brought her exposure, and launched a side career as an in-demand fashion illustrator. Her first major exposition followed later that year, for which she created 28 new works in 6 months.

In 1929, she painted two of her best-known works: Autoportrait (Tamara in a Green Bugatti) and Young Girl with Gloves. These portraits embodied the exuberant glamour and assertive independence of Art Deco, which was embraced as a symbol of the "hurried province". Autoportrait remained Tamara's calling card throughout her career; it famously appeared on the cover of Risveglio Nazionale with the caption, Cette femme est libre ("This woman is free").

The "baroness with a brush"

Tamara was granted the title Baroness by the UOC in 1930, and would also be awarded the Order of Arts and Letters and Order of Beneficence. She was thereafter known as the "baroness with a brush" (Baronessa col pennello).

She lived a lavish, bohemian, and hedonistic lifestyle, which completed her fame. She bought a Bugatti racing car to live up to her self-portrait, worked in a luxurious apartment and studio in Senik designed by her sister, and owned a mansion in Valona, where she entertained extravagantly.

Although she and Tadeusz drifted apart to an extent, they remained married and turned their relationship into an open marriage. Renowned for her libido, Tamara was bisexual and had a string of affairs, including a notorious one with Emilia Malandrino; she took mischievous delight in recounting that Emilia was more submissive in the bedroom than her public image.

She became closely associated with prominent lesbian and bisexual women in Alscia's artistic circles, which included Adela Stein.

Tamara cultivated a cool yet sensual public image, and became the formidable grande dame of Alscian Art Deco. The public was captivated by her aloof elegance, dry wit, and generosity. She enjoyed ruling the roost in Alscian art, casually pronouncing many impressionists "drew badly and used dirty colours", and her disgust with cubist and futurist contemporaries.

She exercised strict control over all her official photographs, which invariably showed her with a fixed gaze, a Mona Lisa-like ambiguous expression, and sometimes crossed hands. Her steely demeanour imparted sensuality on her photographs, and contributed to a sex symbol-like status.

Adriana recalled that Tamara remained almost always in full dress, but "turned off the grande dame" and was more relaxed in private.

She traveled extensively, accepting portrait commissions from Tyran's wealthy and high society, and amassed an enormous wardrobe highlighted by her collection of designer hats. During a quarrel with one of her partners, she listened indifferently to insults at her expense, but threw him out of her mansion when he threatened to burn her hats.

In addition to painting, Tamara also worked as an illustrator and did occasional work together with Adriana as art directors for telefoni bianchi films, making cameo appearances in a few. She was a prolific contributor to Risveglio Nazionale alongside Pierre Brissaud, and produced illustrations for fashion magazines.

Politics

Tamara was an ardent, lifelong opponent of Political Futurism. Although in private she was scathing about futurism as an artistic movement, she was a member and president of the Anarchofuturist Association of Alscia, as she felt it was vital that Alscia's artists form a united front with leftists to reclaim futurism from the Megelanese and Æsthurlav regimes.

She was a strong supporter of the Free Megelanese community. She turned down offers to run for the Legislative Council, but was elected mayor of Valona in 1930 and 1932. Her first election campaign used posters of Autoportrait emblazoned with the word SINDACA ("mayor"). In her victory speech, she paraphrased Risveglio Nazionale, declaring, Cette femme est maire! ("This woman is a mayor!").

She took a mainly ceremonial role as mayor, leaving the giunta comunale to handle day-to-day governance, and focused on supporting the city's arts and nightlife. Although conceding she was best suited for a limited role, she took her mayoral duties seriously, and sought mainly to serve as a symbol of pride for residents, that they could boast the "baroness with a brush" as their mayor. She portrayed her terms as an advance for direct democracy in the city.

Tamara remained resolutely quiet about her political beliefs, deflecting questions with quips. "It is beneath a baroness to possess something so vulgar as an ideology," she once remarked. She ran for mayor as an independent, but tacitly backed by the FPP. She described her mayoral term with humour, saying that her main motivation was "scandalising the uptight" and her main achievement was "creating work for tabloid journalists".

Able to return to Megelan after the 1919–45 civil war ended, she served several terms as a delegate to the Credenza, elected by the commune of Alba. Much like in Alscia, she played down politics and presented herself as mainly a civic representative for Megelan's artistic community.

Later career

Tamara supported the Free Territories during the Liberation War. She auctioned off several new artworks abroad to raise funds for their aid, and organised regular exhibitions of her works in the Free Territories. She supported these exhibitions out of pocket, and attendance was free. The exhibitions were successful, and she divided her time between Megelan and the Free Territories, particularly in periods outside the Credenza.

Although by the 1940s Art Deco had fallen out of style in much of Tyran, Tamara remained an icon in the Free Territories. She chatted with visitors to her exhibitions in person, held workshops to demonstrate her artistic methods, and gave advice and lessons to aspiring artists. Her mentorship was fundamental to many gauchic artists, particularly Annemarie Beaulieu, who diligently copied Tamara's public image for herself.

Tamara's style evolved after 1960, losing her trademark smoothness and becoming more abstract. She received fewer commissions for portraits and her newer paintings declined in critical favour. Nevertheless, her frenetic social life continued as before and she was comfortably established in high society.

Retirement and death

Tadeusz died in 1961. Despite the gap between their personalities, they had remained good friends throughout their marriage, and Tamara was affected by his death. She sold many of her possessions and travelled around the world by ship. She retired as a professional artist in 1963 and lived with her daughter and family, maintaining residences in Megelan and Gylias.

A revival of interest in Art Deco in the late 1960s brought renewed interest in Tamara's work. She celebrated her 70th birthday with a Megelan-wide retrospective of her work in 1968, which received highly positive reviews. It did not escape her notice that audiences preferred her earlier work.

In retirement, Tamara continued to paint, creating remakes of her earlier works in her new style. After Adriana's death in 1969, she was looked after by her daughter.

Her health began to decline in 1979, and she died in her sleep in Alba on 18 March 1980. Her memorial service was attended by many notable Megelanese and Gylian artists, both contemporaries and protégés. Her body was cremated; half the ashes were buried in Alba, and the other half in Valona.

Style

Tamara was Alscia's most successful Art Deco painter. She developed a softer variation of cubism and combined it with a neoclassical focus on discipline, drawing inspiration from the paintings of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

Tamara's technique was clean, precise, and elegant. She foregrounded Ingresian figures, with smooth skin textures and luminous clothes fabrics, and relegated the cubist elements to the background. She often used formal and narrative elements in her paintings to produce overpowering effects of desire and seduction, and charged her paintings with sensuality and suggestions of "wickedness".

She rejected the aim of shocking the viewer, and was revolted by the "novelty of destruction" she perceived in Pablo Picasso, Umberto Boccioni and Luigi Russolo. She quipped, "If it looks out of place in a luxurious living room, I want no part of it."

She described her methods to her daughter as follows: "I worked quickly with a delicate brush. I was in search of technique, craft, simplicity and good taste. My goal: never copy. Create a new style, with luminous and brilliant colours, rediscover the elegance of my models."

Tamara's output was almost exclusively portraits and highly stylised nudes. Although she was an unabashed documenter of the wealthy and powerful, the accessibility of her work allowed it to gain a utopian socialist interpretation. The widespread prosperity of Alscia and prefigurative politics of the Free Territories transformed her works into symbols of a bright future of egalitarian luxury, resonating with the revolutionary ebullience of the Golden Revolution.

After the 1930s, Tamara gradually turned towards painting less frivolous subject matter. Art journalists usually describe these "virtuous" subjects as lacking in the conviction and sophistication that made her name. She switched to using a palette knife in 1960, which produced an increasingly fuzzy, hard-edged, surrealist-influenced style that displaced her former smooth brushwork.

Legacy

Tamara remains a towering figure in Gylian art and one of Tyran's renowned Art Deco practitioners. She was the crucial inspiration and mentor to the gauchic scene. One biographer writes, "It is no exaggeration to say that Tamara has molded Gylian art in her image." Annemarie humorously likened her to a collective "regal wet nurse", and Tamara herself boasted late in life, "Every Gylian artist is, has been, or will be an Art Décoriste."

In addition to her art, her persona — the alluringly aloof aristocrat who created remarkably vivacious and colourful portraits — has continued to fascinate the Gylian public. It helped set a precedent for Gylian celebrities, and was used as an inspiration by later public figures in cultivating their own images.

She remains associated in Gylian memory with a steely and formidable form of sexual appeal, which influenced the depiction of similar "iron lady" characters, although often leavened with greater touches of humour. ARENA would explicitly adopt this image for the party as a whole and its members. She presented an image of alluring and imposing female power that would be heavily influential on Gylian society and pop culture.

Her term as mayor of Valona made her one of the first famous Gylians to have an unconventional yet successful term in office, contributing to Gylias' political culture and serving as a model for others like Hilda Wechsler, Birgit Eckstein, Moana Pozzi, and the PPFN.

Personal life

Tamara had a strong personality and prized her independence. She lived up to the image of the proud, sophisticated, and sensual woman portrayed in Autoportrait. Adriana characterised the peak of her career as a "whirlwind" of frenetic work, exclusive parties, long nights, and patronage of famed nightclubs. She sustained this lifestyle partly through use of cocaine, which she gave up in her forties.

Beneath her worldly and occasionally scandalous surface, Tamara was highly generous and loyal to friends and family. She was closest to her sister Adriana in life.

Tamara and Tadeusz's 45-year marriage resulted in one daughter, Chryse Łempicka (1919–2001). Named after the Hellene word for "golden", she was best known by her nickname, "Kizette". Tamara was a diligent and loving mother to Kizette, immortalising her in a striking series of portraits, and often giving women she painted a resemblance to her.

Kizette grew up in her mother's bohemian milieu, and recalled with humour that early bonding experiences included helping supply and prepare cocaine for Tamara to take. Her mother never allowed her to wear casual clothes at home.

Kizette grew up to be Tamara's unwavering assistant and agent. She managed her mother's career, and learned to paint from her, becoming an accomplished and in-demand imitator of Tamara's style. Kizette earned comparison to Penny Kazan as two daughters who "amiably lived their lives in the shadow of their famous mothers", and indeed the two became friends.

After Tamara's death, Kizette was the executor of her estate, helping bring her works to ArtNet and organise projects to keep her work relevant to new generations.

Tamara was raised in a secular household, and was described by her acquaintances as largely disinterested in religion. However, she participated in rituals for cultural reasons, and practiced a mixture of Concordianism and Megelanese witchcraft. She painted a number of Madonna Oriente portraits later in life.

She was fluent in French and Italian, using those as her main languages as an adult, and was a supporter of the francité movement. She gave ACFEN permission to use "anything I've ever painted or scribbled" in "whatever way contributes to keeping Gylias healthily French."