Gauchic

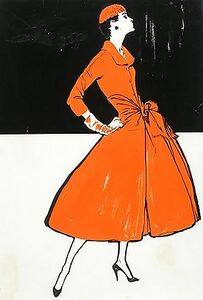

Gauchic (Gylic transliteration: Goşik) is a style of visual art that emerged in Gylias during the 1960s, and became one of the dominant styles of Gylian art. Strongly influenced by genres such as Art Deco and vintage fashion illustration, gauchic is a leading example of Gylian socialised luxury. It has had a significant impact on the country's popular culture and is identified with Gylias abroad, securing a degree of popularity and influence.

Etymology

The term is a French play on words combining gauche ("left") and chic, thus implying "leftist chic".

An alternate English term used with a similar play on words is Glossocialism ("glossy" + "socialism"; Gylic transliteration: Glosoşalisym).

Development

The roots of gauchic emerged in Alscia, which served as a gateway for numerous styles and movements that were disseminated and assimilated by Gylian artists. The most influential in this regard are undoubtedly Art Nouveau and Art Deco, whose identification with the "hurried province" earned them broad popularity among Gylians.

Other notable influences included then-contemporary fashion illustration, reinforced by the first roots of the clothing industry, Miranian ukiyo-e prints, and certain avant-garde movements.

Gauchic developed in the Free Territories. The length of the Liberation War largely isolated Gylian art, and while styles such as Art Deco fell out of fashion in Tyran, they remained popular in the Free Territories — aided in particular by the continued career and influence of Tamara Łempicka. The dominance of prefigurative politics and anarchism led to art that portrayed a hopeful future, and Art Deco provided a ready-made visual language for utopian socialism.

The style flourished after the end of the Liberation War. Annemarie Beaulieu is considered its founder. Her glamorously languid persona — explicitly modeled after Tamara's — and prolific self-portraits served as the "face" of gauchic. Her presence in the Groovy Gylias scene helped bring together the most influential artists into a bohemian, cosmopolitan clique, creating a conscious and trend-setting scene.

The end of the National Obligation period and subsequent economic boom allowed gauchic to reach its height. Its main vehicles became illustrations, posters, and paintings. It became the default visual language of much of the Gylian media, and its use in dedicated magazines such as L'Petit Écho, Silhouette, Downtown, and The Travelling Companion increased its exposure abroad.

Gauchic proved perfectly in tune with the exuberance and optimism of the Golden Revolution. As an artistic movement, it formed close ties with sympathetic movements, including demopolitanism and francité, and was praised by Tomoko Tōsaka as exemplary of her notion of "applied avant-garde". Marguerite Tailler heavily featured gauchic art in the Democratic Communist Party's newspaper The New World and the Revolutionary Communications Office, furthering its ties to social revolution.

Gauchic art played a key role in the Gylian Invasion and was one of its more popular aspects; the contrast between the style's utopian aspects and its classicist appearance drew some amusement or ridicule in avant-garde quarters.

Despite the later retirement or passing of gauchic's first wave of artists, the style has remained dominant in Gylian visual arts to this day. It experienced a notable rejuvenation in the 1990s, aided by a new generation of artists, the end of the wretched decade, a second Gylian Invasion, and the creation of the publinet.

Characteristics

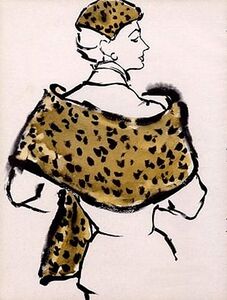

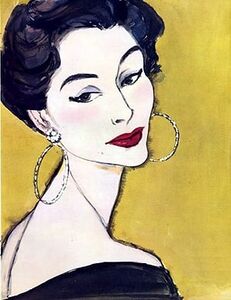

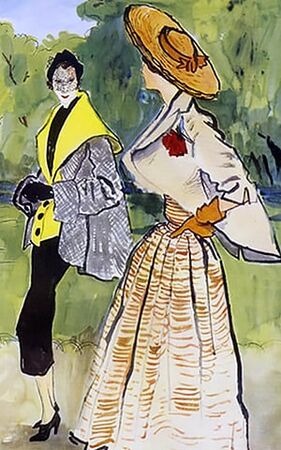

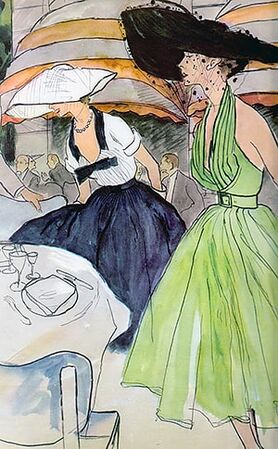

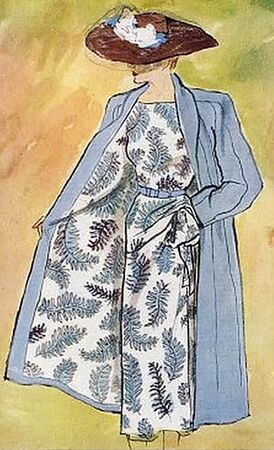

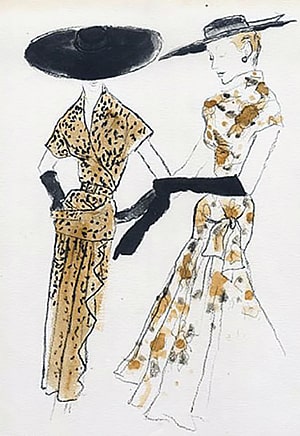

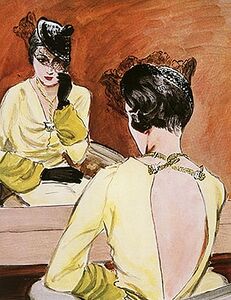

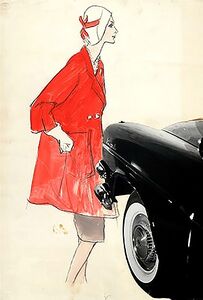

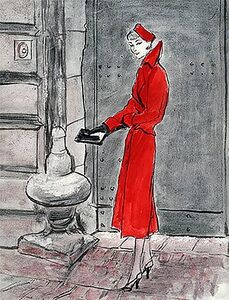

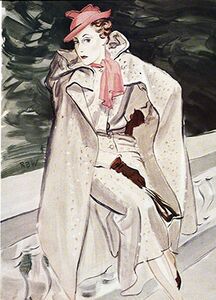

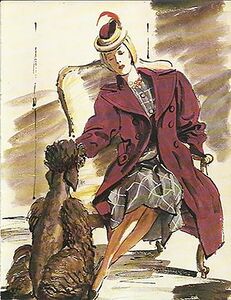

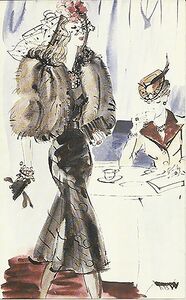

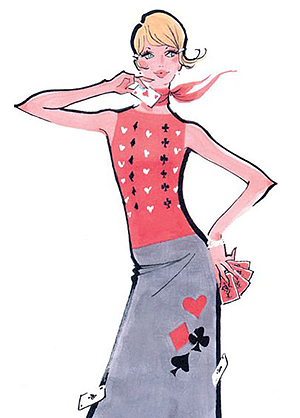

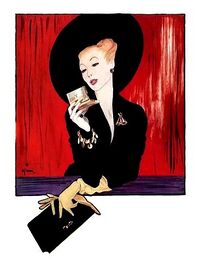

Gauchic art is characterised by its classicist elements combined with subtle avant-garde influences, a trait owed especially to Tamara Łempicka's neoclassical soft cubism.

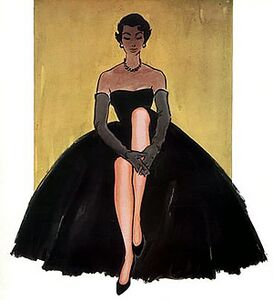

Its defining element is its focus on capturing an atmosphere of elegance and sophistication. Similar to demopolitanism in urbanism and Levystile for clothing, gauchic's conception of elegance is imbued with the anarchist and egalitarian legacy of the Free Territories, based on accessibility and equality instead of class-based segregation of high culture and low culture.

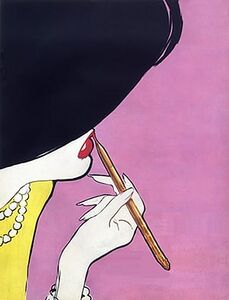

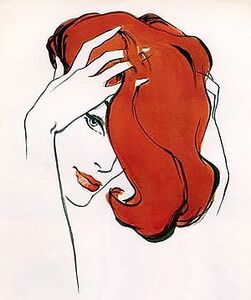

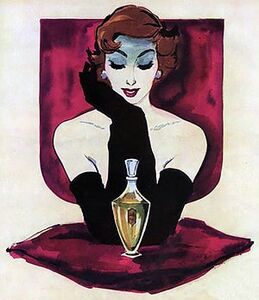

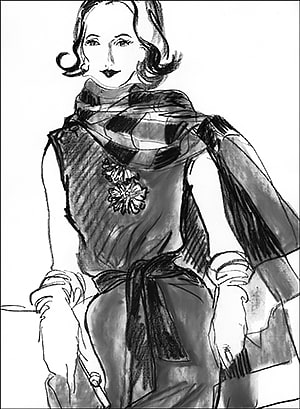

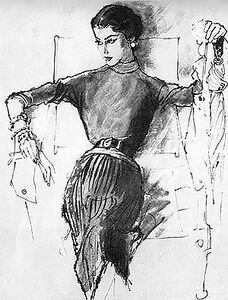

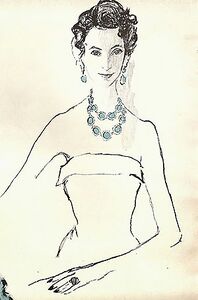

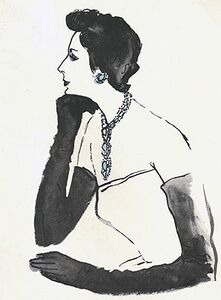

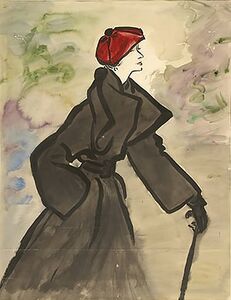

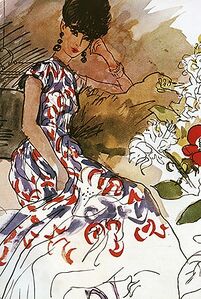

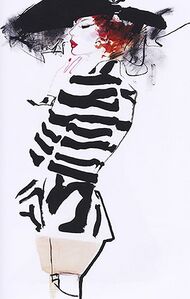

Common methods used to capture this quality include delicate and stylised figures, curving and flowing lines, asymmetric print, alternately muted and striking colours. The subtle influence of futurism and cubism can be detected in the poses, smudged backgrounds, and sharp angles artists sometimes employed to give energy and dynamism to their work.

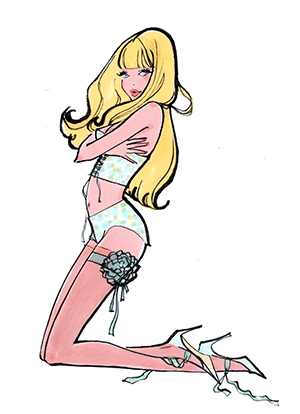

The overwhelming majority of gauchic works depict women, or agendered people with a largely feminine presentation. Images of men are comparatively rarer, and tend to be dandies. Regardless, they are united by their highly idealised depiction: a world of handsome, well-dressed, elegant, and charming Gylians, regardless of gender, representing glamour and modernity.

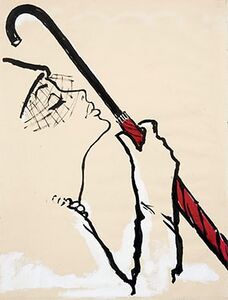

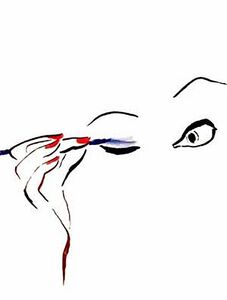

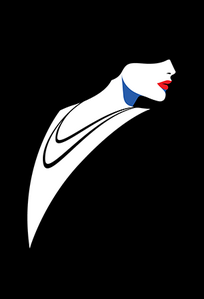

Some artists, particularly of the 1990s generation, famously dispensed with background and depicted their subjects mainly through empty space and few lines, giving their work a dreamlike effect. The use of empty space is also symbolic, inviting the viewer to envision themself in the artwork or adapt it to their own preferences.

Gauchic portraits are also notably charged with discreet or overt sensuality, whether in the eroticisation of clothing and luxury or explicit depictions of nudes and sexual acts.

When not depicting people, gauchic artists still favour socialised luxury as a subject, exemplified by choices of subject such as clothing, cosmetics, champagne glasses, umbrellas, trains, bicycles, and similar objects.

East and west schools

The Eastern school (French: L'école d'est) and Western school (French: L'école d'ouest) are jocular terms invented by Silhouette founder Nan Şernéy to contrast the different art styles of L'Petit Écho and Silhouette:

- The Western school was represented by L'Petit Écho, headquartered in Maveás, Tomes. It has a stronger Art Deco influence, characterised by classicist appearance and frequent use of full colour.

- The Eastern school was represented by Silhouette, headquartered in Senik, Alţira. It has stronger influences from futurism and psychedelia, characterised by sharper angles, restricted splashes of colour, and striking use of empty space.

The concept is seen as humorous rather than a serious classification, but it has found some use. Certain artists may declare themselves mainly inspired or adhering to one of the "schools".

Political aspects

Dating back to its origins in the Free Territories, gauchic has had political connotations. It is informed strongly by anarchism and prefigurative politics. Its widespread adoption and popularity also served as a rejection of socialist realism, high modernism, and other aesthetic styles perceived to be variously totalitarian, grey, or dull, and thus not to be associated with the left.

The preference for depicting female or feminine-presenting subjects is a legacy of Gylian feminism, particularly its strong pushes for female equality and equal representation in the public sphere. Preference for "feminine" aesthetics also accords with the transformation of gender and sexuality norms: with gender being perceived as a spectrum, "feminine" aesthetics are often appreciated primarily on their own merits and resonance with Gylian tastes.

Although primarily leftist in its sympathies, gauchic's utopian aspects have also allowed it to be used at times by Gylian conservatism, which cultivates an identity based on "urbane pragmatism and benign nostalgia", and a slyly buttoned-down image comparable to public figures such as Isabel Longstowe and Cathy French.

The political elements of the style are mainly implicit, and thus have been sometimes missed or misinterpreted by foreign audiences, who would assume gauchic is no different from typical fashion illustrations or advertising art — which indeed was an influence on the style.

Artists

Although gauchic art was dominated by depictions of women, the ranks of its creators were more equal among genders. Cultural commentator Hanako Fukui observes that the first male gauchic artists cultivated images as bons vivants: they appeared impeccably dressed in public and led playboy lifestyles, matching the relaxed sophistication of their subjects.

Most artists took French professional names, reflecting the influence of francité. French had been a prestige language since Alscia, and the francité movement's redefinition of French identity to foreground sophistication and stylishness fit perfectly with the ethos of gauchic. Others used Italian professional names, reflecting the similar prestige of Italian and ties with Megelan's arts scene.

Notable artists

Annemarie Beaulieu (1934–2003) is seen as the founder of gauchic. In contrast to her colleagues, she was mainly a photographer, and set up a large studio, L'Usine, hiring many assistants to help produce her work. The bulk of her oeuvre is glamorous self-portraits, whose playful detachment made her the "face" of gauchic to many, and portraits of both ordinary and famous Gylians, marked by an amused yet generous worldview.

Romain Goudreau (1937–) was a major figure in gauchic illustration, credited with codifying the style. His bold lines, controlled colour, and fluid compositions produced strongly stylised portraits that defined socialised luxury in the visual arts.

Pierre Simon (1938–) is the closest in style to Romain Goudreau, and the two would humorously imitate each other's work on occasion. Pierre's early work features elongated faces and hands on relatively short figures, while his later drawings show realistically proportioned faces with stretched bodies.

Lucien Couturier (1931–2016) was considered a master of gauchic minimalism, being able to portray confident and engaging characters with just a few brush strokes and limited lines and colour.

Émeric (1929–2010) began his career with minimalistic illustrations before moving to a softer, fully-painted style. He was known for the discreet eroticism of his drawings, often showing elegantly-dressed women whose faces were not visible to the viewer.

Melissa Magnani (1933–2001) was one of gauchic's most prolific artists; her finished works required a multitude of preliminary sketches, and she never drew without a model. Her work is characterised by soft lines, subtle charcoal edges, and an atmosphere of aristocratic elegance and light-hearted celebration of femininity. The latter drew on her lesbianism, and its tone was summed up by one of her art books: Femmes — quelles belles créatures (Women — what lovely creatures).

Fabien Bissonnette (1932–2010) was Melissa Magnani's husband, and the two collaborated closely. Their styles were notably similar. Fabien used a pen, producing crisper lines and more precision, and his work was softer and more fluid. He maintained a deliberately classicist style for most of his career, producing work heavily evocative of Alscian-era Art Deco, and his and Melissa's mentor Pierre Brissaud.

Héloïse Favre (1937–) is known for her pencil and charcoal illustrations of delicately slender women, which made her particularly in demand for clothing illustrations.

Euclide Silveri (1935–2000) was famous for his celebrity portraits and close observation of life. His style evolved throughout his career, from accurate monochrome drawings to crayon and watercolours. His most recognised phase is characterised by vibrant colours, large patterns, and abstract forms. His final years saw a shift towards charcoal drawings, without colour, features emerging from patterns of lines.

While not usually classified as gauchic herself, Ðaina Levysti's art style was strongly influenced by it and is very similar to the style, and she was seen as an "honourary member" of the scene: she was close friends with many gauchic artists, socialised with them frequently, praised their work and described them in interviews as "esteemed colleagues".

Alessandro Rocca (1958–) is one of the key figures of the new generation of gauchic. His style is strongly influenced by Romain Goudreau, to the point that he joked he wished to be Romain's successor. His work features fluid composition, restricted lines, and psychedelic splashes of colour against a stark background.

Mireille Fontaine (1982–) earned fame for her minimalistic and Eastern school-influenced style, characterised by bright colours, use of negative space, elegant layouts, and abstract patterns. She has been praised for her ability to convey sensuality through serene facial expressions and close-ups, particularly of lips with red lipstick. She is currently the art director of Silhouette.

Miyuki Morimoto (1958–2013) was an illustrator and photographer. Her work was critically acclaimed for its lively characters, stylised portrayals, and playful spirit. Her specialty was clothing illustrations, and she drew on influences from anime and psychedelic art. She reached her greatest fame as Stella Star's collaborator, handling the art of all their releases from Sweet Stella Star to their retirement, and creating artwork for Readymade Records as well. She was strongly associated with the Neo-Gylian Sound scene, as her visual style matched the scene's demopolitan and musical aesthetics.

Impact

Gauchic's impact on Gylian society and popular culture is immense. It is a dominant style of Gylian art and has achieved widespread popularity and influence. The popularity of illustration ensures that the majority of Gylian books and publications feature gauchic illustrations. The more psychedelic and futurist variation of the style proved an especially good fit for New Wave science fiction.

Through its additional links to similarly influential movements such as francité and demopolitanism, gauchic has secured a prevailing presence in daily life.

Gauchic's role in the Gylian Invasion ensured it was strongly identified with Gylias in Tyran. Its accessibility, refined qualities, and association with iconic Gylian traits such as socialised luxury guaranteed it a significant audience, as well as a degree of influence on foreign artistic scenes.

Eleanor Henderson, who modelled for many gauchic artists during her Gylian career, reflected on the style's enduring popularity in her memoirs:

"Gauchic is a great summary of why the Golden Revolution succeeded and what made it so distinctive. Alone among Tyranian leftist revolutions, it stood for making life brighter and more cheerful, and marshalled its people's considerable ingenuity to achieving that goal. That gauchic became commonplace is the credit of its artists for finding a vision that enchanted a nation: a world of urbane sophisticates, calmly resilient and radical, leisurely strolling about their cities. It is hard to resist such an invitation."