Clothing in Gylias

Gylias has a thriving clothing industry and permissive social attitudes towards clothing. Common traits of the industry include a fusion of utilitarianism and aesthetic quality, emphasis on personalisation, and a lack of dress codes and nudity taboos.

As well as one of the strongest industries of the Gylian economy, clothing is an important part of Gylian culture and social life. Gylian clothing styles have been influenced by climate, the impact of the Golden Revolution, and international trends. Gylians have a reputation in Tyran for good and eccentric tastes in clothing.

History

Emergence

Clothesmaking has existed as an industry since the Liúşai League, but it lacked its current importance during that period.

The conquest of the League by Xevden had a disastrous impact on clothesmaking, which entered a long period of stagnation. It did not receive significant benefits from the Industrial Revolution and transition to capitalism in the 19th century.

In Xevden, clothing mainly had the role of signalling social status. The contrast between the lavish clothing of the elite and the modest, ragged appearance of the poor reflected pervasive economic inequality.

During the Gylian ascendancy, clothing was used as a shorthand symbol for grievances about Xevden. Extravagant clothing came to be associated with oppression and injustice, and was largely viewed with disdain. Nevertheless, a debate occurred among Gylians even at this stage over whether it was possible to reclaim clothing from these associations.

Alscia

The textile industry first established itself in Alscia. As a province of the Cacertian Empire, clothing was used to reflect the province's accelerated development and greater freedoms.

Widespread access to clothing helped replace disdain with a favourable attitude. Alscian fashion was shaped by the province's synthesis of Miranian, French, and Italian ideals of elegance. Contemporary trends from Kirisaki, Akashi, Cacerta, and Megelan became significant influences.

Clothing attained an important presence in culture and daily life for the first time. Governor Donatella Rossetti and several of her female ministers used distinctive appearances to complement their policies, earning the nickname "coats and hats". The blurring of gender roles was reflected in fashion through the popularity of androgyny chic.

Free Territories

The Free Territories were instrumental in shaping Gylian clothesmaking, albeit in an indirect role. They were established on anarchist principles, and built a large network of supply distribution, implementing rationing to meet basic necessities. During the Liberation War, clothing became frugal and versatile by necessity.

Clothes rationing was based on materials and administered through a points system. Initially, various communal assemblies and cooperatives devised their own methods and guidelines to tailor production to availability. Gradually, this evolved into a system of voluntary self-regulation that aimed to preserve a minimum of quality standards while conserving materials.

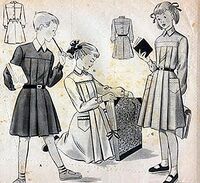

The result of this system came to be known as vêtements règlementaires (French for "regulation clothes") or vêtements utilitaires ("utility clothing"). All-purpose and one-piece garments became popular, such as shirtdresses and coatdresses. Skirts and trousers were reduced to around knee-length to save fabric. Unusual materials began to be used as substitutes for normal cloth. Garments with buttons came to be preferred due to their adaptability for Gylias' climate, and buttons and pockets were frequently used as decorations due to their functionality.

Despite initial fears, rationing incentivised clothesmakers to make do with limited materials, and some rose to the challenge of maintaining style within regulations with remarkable inventiveness. Many Gylians learned textile work in order to reuse, repair and customise their clothes, advised by campaigns and local publications. Rationing unexpectedly aided the Free Territories' social revolution: a shift towards unisex clothing took place, as various items lost gender connotations and came to be worn by everyone.

A spirit of stylish frugality came to characterise Gylian clothing during the period, with fashion accessories and headwear favoured for personal touches. The length of the Liberation War helped entrench public tastes.

Gylias

Clothing prospered as an industry since the transition from the Free Territories to Gylias. The end of rationing in 1961, radical economic reform, resumption of trade and entrance into the Common Sphere significantly benefited access to clothing.

The economic boom that coincided with the Golden Revolution shaped clothesmaking. The last vestiges of reticence towards extravagant clothing were removed through cultural reappropriation. The spread of an ideal of egalitarian elegance allowed universal access to what had been exclusive luxury goods.

The success of clothesmaker Esine Nærzyne and "clothes ideologist" Ðaina Levysti proved fundamental for the new industry. Esine's design philosophy synthesised the distinctive traits of Gylian clothing into a unified approach. Her work in designing uniforms for various public institutions helped impart a glamorous and exciting image to public service.

Ðaina advocated voluntarily maintaining restrictions similar to those that had created vêtements règlementaires. Her 1960 manifesto The Empire of Elegance summed up the ideal of socialised luxury. Its humorous suggestions to accompany radical social change with preserving neatly-dressed "classic" appearances unexpectedly struck a chord with the public.

Notable figures such as Rin Tōsaka, Sakura Tōsaka, Tomoko Tōsaka, Aliska Géza, Julie Legrand, Erika Ďileş, and Marguerite Tailler and the Revolutionary Communications Office helped set an example. The combination of political radicalism and sophisticated presentation came to be widely accepted, and became a popular emblem of revolutionary exuberance.

Socialised luxury had a notable impact on the public sphere. Public organisations adopted stylish uniforms for their workers, giving the public sector an image of glamour and patriotic service that became part of the Gylian consensus. Certain service occupations were preserved due to their contribution to sociality and quality of life, including elevator attendants, tray vendors, tea servers, filling station attendants, telephone operators, and paid dance partners.

Several subcultures formed which used elegant clothing as a symbol of defiance and resilience during the National Obligation period.

1960s–1970s

Left: A georgette reads a newspaper in Velouria, 1964.

Right: A student reading on the steps of Anca Déuréy University, Narsiad, 1966.

The clothing industry came to largely follow Esine's philosophy and example in the 1960s. Clothesmakers relied on personalisation over mass prodution, and aimed to produce clothing that was aesthetically pleasing, functional, and easy to customise. A spirit of frivolity and experimentation became the norm, with touches of eccentricity applied to otherwise sophisticated looks.

The ideals of socialised luxury and understated glamour propelled certain styles to great popularity. Significant among these were the Levystile traits advocated by Ðaina, which influenced the appearance of georgettes, merchants, and hétaïres.

Certain subcultures looked to 19th century fashion and Alscia as an inspiration, fashioning more eccentric and old-fashioned outfits. Gylias' first President Reda Kazan was notably supportive of this trend.

The success of The Beaties, The Watts, The Wells, and The Dandys, among others, inspired many musical artists to devise a common look to go with their music. During the Gylian Invasion, some would use outfits as a lighthearted shorthand for their heritage. The "psychedelic revolution" reached clothing in the late 1960s.

Clothing became a symbol of the liberated and colourful society engendered by the Golden Revolution. Gauchic artists often depicted well-dressed persons, providing inspiration and influence for clothesmakers. Orgone films and the demopolitan movement celebrated glamorous young Gylians and their lives in the cities. Clothing found a niche in Gylian pornography, which explored ways to visually eroticise clothing and dressing.

Saorlaith Ní Curnín waged an influential personal campaign to "beautify" public life, pushing film and television productions to ensure their lead actors at least were well-dressed, and for publications to similarly select only well-dressed images of celebrities to publish, with the aim of raising the average clothing standards of Gylians as a whole. Her efforts were aided by similar preferences among the leading figures of Gylian Television like Eija Nylund, Estelle Parker, and Cecilia Parker.

Certain foreign fashion trends gained acceptance after being adapted to prevailing tastes. The francité movement cultivated an appearance of French fashion to complement its promotion of French identity in Gylias. Other clothing items such as the combination of thin trench coats with berets also gathered a following due to their identification with French notions of sophistication.

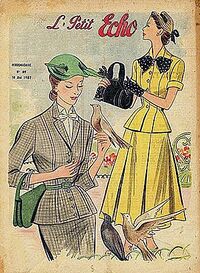

The do it yourself philosophy engedered by the Free Territories continued to be promoted by campaigns, magazines — including L'Petit Écho, Silhouette, teen —, and various advice books, pamphlets, and informal meetings. Gylian customers by and large bought their clothes from various companies and customised them to their tastes.

With additional exposure from the Gylian Invasion, clothing became a significant export. The low exchange rate of the þaler made exports cheap, and Gylian aesthetics attracted foreign customers who sought haute couture at affordable prices.

1980s

The crises of the wretched decade affected clothing. The loss of the Golden Revolution's exuberant atmosphere led to a modest turn in designs.

Various trends gained a degree of popularity in the 1980s, some in reaction to the wretched decade, such as the flamboyance of new wave, New Romantic, and cyberpunk.

The designer Kaede Nakano began her rise to fame in the decade. She created a style based on the appearance of feminine white-collar workers, including bright shirts or blouses, dark suits, and bows and waistcoats. Her company initially built a following among Miranian Gylians, coming to be jokingly described as their "national uniform".

1990s–present

Economic recovery and renewed national optimism rejuvenated the clothing industry in the 1990s, heralding a return to more flamboyant experimentation.

Aishwarya Devi's work in the Mathilde Veira government to restrain consumption and reduce waste caused the industry to devote more attention to exports, and cemented the predominance of sustainable clothing. Textile recycling also assumed greater importance.

Influenced by events like the Decleyre Summit and the establishment of the Social Partnership Program, cultural attitudes towards entrepreneurship grew more positive. As a result, Kaede Nakano designs grew in popularity nationally, and businesswomen such as Agathe Sanna, Marie-Agnès Delaunay, Saira Telyn, and Kanna Miyashita became style icons.

Maki Nomura, Stella Star's lead singer, also became a style icon during the decade, helping popularise a trend towards retro style and vintage clothing. Her versatile and diverse wardrobe contrasted with pop stars with a more constant appearance, like Asuka, Misato Katsuragi, Elena Tessari, and The Chrysalides.

Another trend to emerge in this period was "levieillestyle", a variant of Levystile that emphasises highly elaborate dressing to cultivate an elegant appearance in old age, and frequent use of black–white contrast. Notable practitioners and popularises included Carmen Dell'Orefice, Esua Nadel, Electra Galanou, Liisa Salmela, and Jane Birkin.

The growth of the internet in Gylias led to a controlled, gradual shift towards online retail by clothesmakers and retailers.

Characteristics

Gylian clothing is generally defined by casual elegance and quirkiness. Garments are made to be both functional and aesthetically pleasing. Eclectic combinations of different styles in a single wardrobe are common. Garments are usually made out of thinner fabrics, in order to maintain comfort in the tropical climate.

While Gylias has a strong clothing industry, it does not have a fashion industry based on cyclical changes of style or practices such as fashion weeks and runways. The expectation is that individuals will have their clothes tailored or customised to their preferences.

The industry is known for preferring illustration of clothes over photography. This is helped by the widespread popularity of illustration, its close ties to the industry, and the enduring influence of gauchic. Illustration is seen as showing proposals that can be modified, while photography is perceived as normative.

A strong do it yourself culture exists around clothing. Homemade clothing and knowledge of textile work is common. Many magazines and media outlets publish patterns for outfits, and customisation of bought clothing is widespread.

Gender

Gylian clothing is unisex. However, during the Golden Revolution's shift of attitudes towards gender, the practice of reclaiming and socialising notions of elegance and luxury have produced a trend towards androgynous appearances. The non-gendered prevalence of female-indentified clothing such as dresses and skirts is due to their suitability for the country's climate.

Illustrations for Gylian clothing always use character models that are androgynous or ambiguous in appearance, reinforcing the principle that clothes are suitable for all to wear.

Journalism

Clothes journalism in Gylias is based on a combination of consumer protection-oriented unbiased product testing and commentary reminiscent of arts criticism. Common hallmarks include technical details, attempts to describe the item being reviewed as objectively as possible, and often literary-influenced passages that attempt to convey the feelings produced, with clear demarcations between each section.

Organisation

There are two main organisations governing clothesmaking:

- The Association of Clothesmakers and Textile Workers — a trade union representing clothing industry workers affiliated with the General Council of Workers' Unions and Associations.

- The Gylian Clothing Federation — a trade group and governing body affiliated with the National Cooperative Confederation.

The GCF is responsible for coordination within the clothing industry, quality standards and control, promoting it at home and abroad, and organising specialised education in the field.