Rail transport in Menghe

| Menghe | |

|---|---|

A passenger train on the Wihae-Daegok line. | |

| Operation | |

| National railway | Menghe Railways |

| Statistics | |

| Ridership | 1,467 million (2019) |

| Passenger km | 490 billion |

| Freight | 1.93 billion tons |

| System length | |

| Total | 106,085 km |

| Double track | 82,721 km |

| Electrified | 55,573 km |

| Freight only | 38,016 km (CargoMax) |

| High-speed | 21,314 km |

| Track gauge | |

| Main | 1,435mm and 914mm |

| High-speed | 1,435mm |

| 1,435mm | 77,234 km |

| 914mm | 10,209 km |

| Features | |

| No. tunnels | 3,021 |

| Tunnel length | 1,961 km |

| Longest tunnel | Kimhae Tunnel 12,301 m |

| No. bridges | 46,308 |

| Longest bridge | Myŏng'an Road-Rail Bridge 8,272 m |

| No. stations | 8,724 |

| Highest elevation | 13,232 m |

| at | Tusan Plateau |

Rail transport is a major mode of long-distance transportation in Menghe. With over 100,000 kilometers of track in operation at the end of 2020, Menghe has the largest rail network in Septentrion, and it is one of the leading countries in the number of passenger trips per year. It also has the region's largest high-speed rail network, with over 21,000 kilometers in operation and ongoing construction on an additional 3,000 kilometers, far surpassing the next-largest high-speed rail networks in Dayashina and Tír Glas.

Menghe Railways, a state-owned enterprise, has a monopoly on nearly all long-distance rail transport. The state railway monopoly has existed since 1964, though its organization has undergone several changes since then. Municipal public transportation systems are managed by local governments rather than the national railway corporation, with joint management of some commuter rail services. Other notable exceptions include tourist railroads and short-distance freight lines.

History

First railroads (1860-1901)

The first railroad in Menghe was built in 1860, after the Brothel War opened the country to additional foreign investment. It was a 600mm narrow-gauge railway which ran 49.1 kilometers from the west gate to the Sieuxerrian port cession on the coast of Hwangsa Bay. While ostensibly for moving passengers and light freight between the port and the city, it was also intended to garner Menghean interest in railroad construction, in the hopes of attracting future contracts from the Myŏn dynasty.

The Myŏn dynasty collapsed in 1867, ushering in the beginning of the Three States Period. At the start of this period, the State of Sinyi expelled all foreign advisors from the country, and the Namyang Government in the south was mainly concerned with consolidating its political structure and financing the Rebel Suppressing Army in the north. Seeing an opportunity, an Anglian rail company offered to build a medium-gauge (4 foot 8½ inch) railroad from Sunju to Insŏng with full foreign financing, in return for exclusive rights to civilian passenger and freight operations on the line. The Namyang leaders agreed, and the line began construction in 1869, opening in 1870.

In 1871, Namyang leaders laid out plans for a new long-distance railroad linking the front lines to the country's southern ports, to speed up the movement of arms and reinforcements. The 201-kilometer line from Yŏng'an to Hwasŏng was built first, as transport south of Hwasŏng could be conducted by canal. The 863-kilometer line from Hwasŏng to Insŏng opened in 1874, after three years of construction, allowing trains to cover in less than two days a journey that would take over a week on a river barge. The Chanam-Chŏnjin railroad, another Anglian venture, was built between 1876 and 1878, with a connection to the other mainline at Unchŏn added in 1880. Because the Meng and Ŭm Rivers were over a kilometer wide along their southern reaches, it was not feasible to run rail bridges over them at the time, and rolling stock had to use train ferries at Chŏnjin and Insŏng. This entire network was built in 4ft 8½ inch gauge (1435mm), though the Sylvan-built Altagracia North Line (built 1888-1891) used 1668mm gauge, and a mining route bringing coal to Changban used 2ft 6in (762mm) gauge.

The rival State of Sinyi was slower to embrace railroads, due to its origins as a movement against Western influence. But when faced with the urgent need to reopen shipping between the Meng River canal network and the coastal ports, the Gwangmu Emperor eventually authorized a rail link in the east. Engineers surveyed four possible routes: Ranju to Yŏngsan, Hyangchun to Yŏngsan, Anchŏn to Taekchŏn, and Kimhae to Taekchŏn. While the fourth route was longest, it required the shortest distance through mountainous terrain, and was therefore the least expensive. The section from Kimhae to Dongrŭng opened to traffic in 1877, and the overland section to the highest navigable point on the Gyŏng river opened in 1879; the full route to Taekchŏn was completed in 1880. Two years later, when the Sunchi Emperor ascended to the throne, he ordered that this line be extended to Junggyŏng and Sapo, and moved the capital to Donggyŏng (formerly Kimhae). A separate railway between Songrimsŏng and Baekjin was built between 1879 and 1881, and in 1887-1889 a railway between Songrimsŏng and Jinyi connected it to the rest of the network. Apart from a 760mm coal mine route in North Donghae province, all of Sinyi's railways were built in 914mm (3 foot) narrow gauge, which allowed for smaller and cheaper bridges, tunnels, embankments, and mountainside paths. Sinyi relied extensively on engineers from Fyrland to plan the routes and manufacture specialized equipment, but financed the railways from the military budget, and initially operated a state-run rail service to collect revenue. This service was later privatized in 1889, becoming the Donghae Railway Company.

Indpendently from the other two states, the Uzeri Sultanate built a 426-kilometer railway from Quảng Phả to Hồng Xuyên in 1884-1886. While this route carried some passenger services, it was mainly intended for freight, shipping coal and sugarcane from the northern side of the mountain range to the southern ports for export. The rails were built by a Sieuxerrian company in meter-gauge, and the rolling stock was Sieuxerrian in origin as well.

When the Three States Period ended in 1901, Menghe had roughly 6,600 kilometers of track, including track laid in the Uzeri Sultanate. Unfortunately, because it originated from a variety of independent projects, the network lacked a single unified gauge. Not counting streetcars, at least seven different track gauges were used in total: 600mm, 720mm, 762mm, 914mm, 1000mm, 1435mm, and 1668mm. Of the seven, 914mm and 1435mm were most common, as these were the official track gauges of the State of Sinyi and the Namyang Government, respectively.

Consolidation and expansion (1901-1964)

After the formation of the Federative Republic of Menghe, the Ministry of Railways faced the daunting task of unifying this diverse rail network. The first step was to re-gauge the Sinyi Main Line, which now extended from Chŏnju to Baekjin. Because of the large difference in gauge, it was not possible to re-gauge the existing line using the same sleepers, and because of the high volume of freight, it was necessary to avoid prolonged closures. The eventual solution was to build a set of 1435mm tracks parallel to the original route, shift all traffic onto those tracks, then close down the 914mm tracks and replace them with 1435mm tracks on new sleepers. In the process, the already-crowded single-track route would be replaced with a dual-track corridor. This expensive undertaking began in 1903 and was not fully completed until 1909. Even then, only the main Baekjin-Insŏng portion was in 1435mm: because the original Sinyi route through the Donghae mountains relied extensively on tunnels, bridges, embankments, and switchbacks, all of them with a narrow loading gauge, it was not feasible to re-gauge this portion of the line or add a second set of tracks. Instead, freight and passengers would have to switch trains at a break of gauge where the two sections of track intersected.

During construction, Menghe also built rail bridges across the Ro river at Insŏng and the Meng river north of Hwasŏng. At 945 and 1440 meters long, respectively, these were the longest bridges ever built in Menghe. For the time being, Chŏnjin still relied on a train ferry.

Merging railroad networks also required administrative reforms. For service from Insŏng to Baekjin, the government financed the creation of a new private company, Menghean Federal Railway. Federal Railway was given control of the long-distance mainline, while other lines remained under the control of other private enterprises, such as the Donghae Railway Company. Initially, federal regions could also set their own regulations on track gauge and loading gauge for regional lines, allowing Donghae to keept its extensive 914mm network. This law was revised in 1917 to require 1435mm track and a standard loading gauge on new lines capable of long-distance service.

After re-gauging the Baekjin-Insŏng mainline and bridging the Meng and Ro rivers, Menghean Federal Railway turned its attention to a new project: the Great Northern Railroad, which would open up the interior to development and connect its coal mines to coastal ports and industrial centers. Construction began in 1910; when it finished in 1919, the single-track route covered a total of 1,843 kilometers, linking Suhait with Jinjŏng, Ryŏjin, Hapsŏng, and Songrimsŏng. Paired with new branch lines to coal mines, it contributed to a surge in heavy industry development in the northeast.

As expansion of the network continued, concerns over interoperability led to the so-called "gauge wars." In 1919, Federal Railway sued Donghae Railway on the grounds that its recently completed coastal extension from Anchŏn to Ranju created a "long-distance mainline" and should fall under Federal's ownership. This suit was unsuccessful, but another one in 1921 forced Unryŏng Rail in the southeast to suspend work on a 913mm line from Yŏngjŏng to Gyŏngsan and transfer ownership of the project to Federal, which expanded the gauge to 1435mm, planned a link to Chŏnju, and resumed construction. Meanwhile in the west, Federal built its own track from Insŏng to Pyŏng'an via Chimyang, as the Baekyong Gulf Line via Altagracia and Giju was built in Sylvan 1668mm gauge. The debate peaked in 1926, during a heated legal dispute over whether Federal or Unryŏng had rights to build a new line from Goksan to Musan via Daegok; Unryŏng already had 913mm tracks in the area, but Federal's managers insisted that the route should be built in 1435mm because it would be a strategic coal shipment route. After his coup in 1927, Kwon Chong-hoon decided the matter in Federal's favor, a decision which forced Unryŏng Railways into bankruptcy.

The resolution of the "Gok-gok" case marked the beginning of a harsher standardization policy under the Greater Menghean Empire. A military commander himself, Kwon believed that long-distance rail transport was vital to national defense, and ordered that all new tracks west of the Donghae Mountain Range be built in 1435mm gauge. To enforce this decision, he ordered that the Pyŏng'an-Quảng Phả and Pyŏng'an-Sunju routes be converted to 1435mm gauge. After Fenix Rail, a Sylvan company, refused to comply, Kwon nationalized its assets and transferred them to Federal. Kwon also launched a major nationwide railway building program in an effort to bring more marginal cities onto the line and improve supply lines near the frontiers. This included a separate 1435mm route from Jinyi to Donggyŏng, which finally linked the capital to the Federal network, and which was later expanded to Baekjin via Chŏngdo. It also included an ambitious 2,398-meter road-and-rail bridge at Chŏnjin, completed in 1938, which finally allowed direct service to Chanam.

The first few years of the Pan-Septentrion War brought a renewed boom in railroad construction, as the Greater Menghean Empire sought to boost industrial capacity and supply the front line. Of particular note are four rail lines built into Maverica and one built across Dzhungestan, all of them built with the help of Allied prison labor. As the war progressed, however, new construction and even regular maintenance rolled to a halt, as military planners directed more steel and manpower to military production. Allied bombing damaged many marshalling yards and bridges, including the long bridge across the Meng River at Chŏnjin. The Menghean War of Liberation brought additional damage to the network, as guerilla fighters sabotaged bridges, derailed trains, and pulled up rail spikes to melt down into homemade weapons. The Allied Occupation Authority carried out routine repairs of damaged lines, and even upgraded the Great Northern Railroad to double track, but as the war dragged on, the debt-laden Republic of Menghe government struggled to finance even basic maintenance.

| Track gauge | Distance of track |

|---|---|

| 1435mm | 23,937 km |

| 1000mm | 346 km |

| 914mm | 3,492 km |

| Dual 1435+1000mm | 773 km |

| Dual 1435+914mm | 945 km |

| Other gauges | 469 km |

| Total | 29,962 km |

Rail transport in the DPRM (1964-1987)

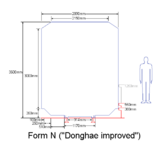

After their victory in 1964, Communist leaders concluded that urgent action was needed to repair the country's damaged rail network. Their first step was to nationalize all private rail companies in Menghe, placing their assets under the direct management of the Ministry of Railroads. Next, they set out to rationalize the private networks' wide variety of track gauges and loading gauges. By this time, nearly all meter-gauge track in the southwest was on dual-gauge lines; the middle rails were removed, and exclusively 1000mm lines re-gauged. In the east, economic planners concluded that the 914mm network was too vast to re-gauge, especially considering how much of it ran through tunnels. Instead, they condensed the many 914mm loading guages into two standards, one based on the oldest, narrowest lines (D) and one which was initially designed for dual-gauge tracks (N). All new construction would use Form N gauge, and all lines which could not be modified for Form N would use Form D. As many bridges and tunnels had been damaged during thirty years of war, new construction created an opportunity to rebuild damaged lines to Form N standard.

The years that followed saw a breakneck campaign of new railroad construction. Between 1964 and 1988, the length of railroad track in Menghe increased 65%, with most of the increase taking place during the 1970s under the productionist leadership of Sim Jin-hwan. In the east of the country, this included the completion of the Donghae Mainline, planned since the 1930s: a 1435mm, double-track railroad which ran the full distance from Baekjin to Gyŏngsan with no break of gauge. Further inland, the New Frontier Route linked Suhait to Sunju via Suksŏng, though it saw disappointingly little traffic. Two new railroads across the Donghae Mountains greatly increased the volume of passengers and freight which could move between the east coast and the central plains, relieving pressure on the existing bottlenecks in the line.

Because railway construction was part of Sim Jin-hwan's campaign to promote rapid industrialization under a state-socialist model, there was a particularly heavy emphasis on building rail lines which would serve mines, refineries, and factories. Construction also gave disproportionate attention to the interior region, which was better protected from Dayashinese bombing or invasion in the event of a war. Intercity passenger transportation was a secondary priority, and there was little advancement in commuter rail, as the Household Registration System prevented rural residents from working in the cities. In general, any workers able to afford daily rail transport to the cities already had state-owned dormitories near their workplaces.

Ryŏ Ho-jun's ill-conceived rural industry campaigns stalled several railway construction plans, undercutting plans to reach 50,000 kilometers of track by the 20th anniversary of victory in the War of Liberation. There are several reports of local governments ordering villagers to pull up rail spikes and even steal entire sections of track in order to meet arbitrary quotas for steel ingot production. A route from Mindong to Yanggang, already under construction, was torn up in 1986 to punish locals for attempting an uprising during the Menghean famine of 1985-87. In 1987, the Communist Party even ordered that workers in the east coast tear up strategic rail lines to hamper any invasion from Dayashina, though these plans were never fully implemented. Despite the political instability, the 1980s did see the construction of some new railway links, especially strategic routes through the mountains to reinforce the coast.

| Track gauge | Distance of track |

|---|---|

| 1435mm | 43,075 km |

| 914mm | 3,703 km |

| Dual 1435+914mm | 2,557 km |

| Total | 49,335 km |

In the economic miracle (1987-present)

Menghe experienced its largest railway building boom after 1987, when Choe Sŭng-min came to power and ushered in a series of economic reforms. Rapid industrial growth led to a surge in the demand for freight and passenger transportation, and provided additional funds and resources for infrastructure building. There were also some continuities with the DPRM's policy, as the Socialist Party ordered the construction of more rural commuter trains and stopping trains to serve disadvantaged areas in the east. In 2003 control of the rail network was transferred to Menghe Railways, a mixed-motive state-owned enterprise, part of an effort to improve service and efficiency.

Freight lines were an early focus in post-'87 railroad construction. The transition from a self-reliant economy to an export-focused one required a major re-orientation of the freight network, which previously served the inland cities rather than the coastal ones. In an effort to link these two areas, the Ministry of Railroads ordered the construction of new tracks with an enhanced "CargoMax" loading gauge (6200 by 4800 mm), to allow the use of double-stack rail cars and large autoracks as well as other types of oversize freight. Because the minimum height of overhead wires was set at 6400mm, this required grade separation of oversize and electrified routes. The diplomatic crisis with Maverica and Innominada following the Ummayan Civil War added military exigency to economic demand, leading to the building of new rail routes in the southwest to bring supplies to an increasingly militarized border.

The crowning achievement of Menghe's railroad modernization was the construction of an expansive high-speed rail network. Throughout the late 1990s, engineers worked to speed up trains on existing core mainlines, installing new track and ballasting equipment to allow speeds of up to 200 kilometers per hour. The first dedicated high-speed line, linking Sunju and Insŏng, opened on December 14, 2006, and was built with extensive Themiclesian support. Over time, as construction continued, Menghean engineers gained their own experience in high-speed rail construction, and by the early 2010s were building new lines and designing new rolling stock without foreign aid. As of mid-2020, Menghe has 21,314 kilometers of operational high-speed track, the longest high-speed network of any country in Septentrion.

Administration

Ownership

Nearly all long-distance railway service in Menghe is controlled by Menghe Railways (멩국 철로 / 孟國鐵道, Mengguk Chŏldo), which is sometimes shortened to Gukchŏl or National Rail. Prior to 2003, railways and rolling stock were directly administered by the Ministry of Railways and financed out of the government budget. As part of the 2003 ministerial reorganization, the Ministry of Railways was rolled into the new Ministry of Transportation and Communications, and formally renamed as the Railroad Regulatory Agency (RRA). Ownership of railways and rolling stock was transferred to Menghe Railways, a state-owned enterprise.

Menghe Railways is formally designated as a mixed-motive state-owned enterprise. This means that its finances are separate from the Ministry of Transportation's budget, and the promotion of managerial staff incentivizes profitability, but the corporation is still required to meet public service requirements set by the Ministry of Transportation. Examples of these requirements include:

- Building strategic freight railroads as directed by the Ministry of National Defense;

- Building projects proposed and financed by the Ministry of Economic Development;

- Operating passenger service in rural or marginal areas; and

- Charging affordable ticket prices, as designated by the Railroad Regulatory Agency.

For example, many frequent-stop railway lines in rural areas are not profitable and would be shut down by a private carrier, but Menghe Railways continues to operate them in order to provide adequate transportation to rural residents.

Private companies are forbidden from building or operating intercity railway lines, except where the RRA explicitly authorizes them to do so. Most of these exceptions cover foreign trains which stop at Menghean stations, including through service on the Trans-Hemithea High-Speed Railway. Since 2011, Menghe Railways has experimented with allowing investors to buy and sell stock, but the Menghean government retains a 55% controlling stake.

While its budget and accounts are separate from the national budget, and although managers are rewarded for reducing cost-revenue gaps, Menghe Railways still operates at a loss, and receives subsidies from the national government. These subsidies can be divided into financing for new construction, per-ticket subsidies to incentivize ridership, and support for low-volume lines in marginal areas; most high-volume passenger routes, including the Baekjin-Gyŏngsan HSR route, make money and do not themselves require subsidies.

Classification of tracks

Railway tracks in Menghe are divided into three types, each with different ownership laws.

National railways comprise most of the network, including Inter-city rail, commuter rail, regional rail, and high-speed rail, but also industrial spurs, sidings, classification yards, rail yards, and other supporting infrastructure for the national system. This network is exclusively owned and operated by Menghe Railways, with the exception of some cross-border foreign trains which use its tracks.

Municipal railways are local passenger services confined to a given metropolitan area, in other words urban rail transit. Examples include trams, light rail, and rapid transit, but not commuter rail, which is classified as a National Railway. The category also includes rail yards which serve these systems. Municipal railways are owned and managed by prefecture-level municipal governments, and regulated by each municipality's Transportation Bureau.

Delimited railways are special-purpose railways serving a confined area. Examples include mine railways, funiculars, and people movers inside airports, parks, and malls, as well as rails used to move goods within the property of a factory, shipyard, or other industrial complex. Heritage railways are also included in this category. These railways are owned by whatever entity owns the plot of land they serve; thus a mine railway may be publicly owned or privately owned, depending on whether the mine is publicly or privately owned, but even in the former case it is owned by the state-owned enterprise which operates the mine. Like municipal railways, delimited railways may be linked to the national railway network - for example, to allow the delivery of rolling stock - but they cannot operate on the national railway's tracks outside the owner's property.

Integration of commuter rail service

Since 2010, Menghe Railways has worked to promote integration between nationally-run commuter rail and municipal rapid transit. Originally, becauses these systems were run by separate governments, they had their own maps, schedules, and ticketing systems: passengers transferring from a commuter train to a metro line would have to leave the station and buy a separate ticket. This caused a great deal of inconvenience for passengers, especially as municipal governments began to implement rechargable transit cards and smartphone payment apps which allowed integrated ticketing between metro, bus, and tram lines, but not commuter rail.

Donggyŏng was the first city to experiment with integrated ticketing of commuter rail and municipal transit, introducing a single card and a single app which could be used on both systems. Metro-rail transfer points were modified to allow free passage between platforms without a ticket check, and at the end of a passenger's journey, the total fare was calculated from the shortest route between the stations where the passenger swiped in and out. Revenue was then split between Menghe Railways and the Donggyŏng Metro based on the separate fares for each part of that trip. Other changes were purely superficial, to aid passenger navigation: commuter rail routes were added to metro system maps, and in some cases given Line numbers, with the metro system's logo added to stations. Insŏng, Hyangchun, and Haeju - all cities with large metro and commuter rail networks - followed up with similar experiments.

In 2017, the National Assembly passed a document urging all local governments with municipal railways to pursue integrated ticketing on the Donggyŏng-Insŏng model. Further expansion of integrated ticketing is expected to go hand-in-hand with the expansion of the One-Stop smart card and app, which as of June 2020 is valid for use in 64 cities and on all commuter and regional rail lines.

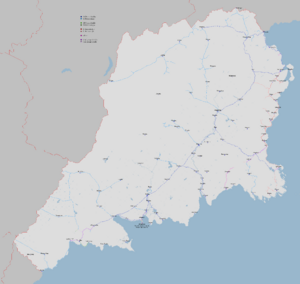

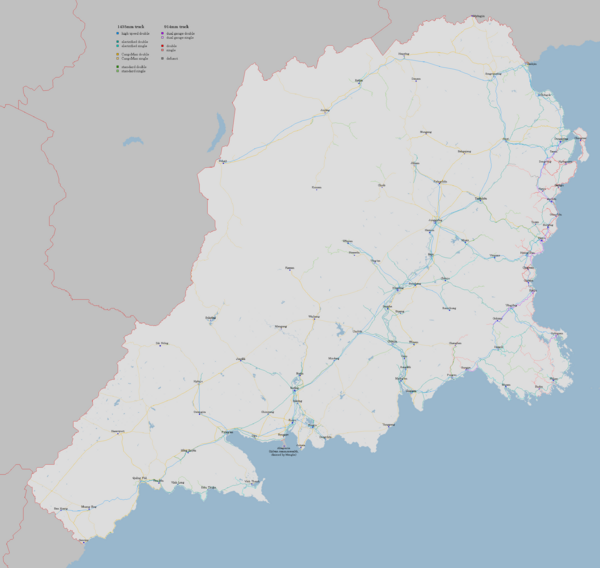

Track network

Menghe has the longest rail network in Septentrion, with 106,085 kilometers of track in operation in 2020. Of this total, 21,314 kilometers are dedicated high-speed tracks with AC overhead wires. When including dual-gauge track in both totals, there are 77,234 kilometers of standard-gauge (non-high-speed) track, and 10,209 kilometers of narrow-gauge track. Overall electrification of the network stands at 52%, but this figure is misleading because CargoMax and narrow gauge tracks cannot be electrified under the Railway Regulatory Agency's safety and clearance laws. When counting only high-speed and conventional 1435mm track, electrification covers 92.3% of the network.

The table below shows the total length of Menghe's rail network at the end of the year in 2020, when the high-speed link between Sunchang and Ramchung begins operational. It only includes "national railway" tracks which are operated by Menghe Railways. Thus, municipal public transit systems, delimited railways in mines and factories, and disused sections of rail are excluded. Tourist rail is excluded, except in situations where tourist trains use the national rail network. These totals also exclude three small sections of 1676mm rail which cross over from Polvokia before entering stations and bogie exchange yards; these add up to less than 10 kilometers of track.

It should also be emphasized that these totals do not include sections of track which are in testing, under construction, or in late-stage planning. Three major high-speed routes are still under construction, and several major cities are in the proces of expanding commuter rail links to their suburbs. As such, the actual total track distances will continue increasing after 2020.

| Type | Single track | Double track | Electrified | Pct Elect. | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High speed 1435mm | none | 21,314 km | 21,314 km | 100% | 21,314 km |

| Conventional 1435mm | 4,348 km | 32,198 km | 32,064 km | 88% | 36,546 km |

| CargoMax 1435mm | 14,899 km | 23,117 km | none | 0% | 38,016 km |

| Dual gauge | 86 km | 2,586 km | 2,195 km | 82% | 2,672 km |

| Narrow gauge 914mm | 4,031 km | 3,506 km | none | 0% | 7,537 km |

| All types | 23,364 km | 82,721 km | 55,573 km | 52% | 106,085 km |

Categories of rail transport

High-speed rail

With over 21,000 kilometers of double track, Menghe operates the largest high-speed rail network in Septentrion, covering three times as many kilometrs of track as the next-largest high-speed operator, Dayashina. As of 2020, this network is still expanding, with ongoing construction on three major high-speed routes: Jŏksan-Nungang-Danam-Hapsŏng in the center-north; Ramchung-Changban-Pungsu in the southeast; and Hyŏnju-Dài Nióng in the southwest. A high-speed shuttle service from Insŏng to Busin is also undergoing testing, though the extension of this route to Wichang and Kaesan has been postponed, and a link from Winam to Onju will open in 2022.

Menghe had a late start at high-speed rail construction, with its first dedicated high-speed route beginning construction in 2002 and opening at the end of 2006. As a result of this late start, Menghe Railways was able to import a number of modern features from the beginning, designing tracks on level terrain to support speeds of up to 350 kilometers per hour. Following a major high-speed construction boom in the 2010s and early 2020s, Menghe has emerged as a leading nation in the design and construction of high-speed rail, and has offered to export high-speed technology to other nations.

Long-distance high-speed rail lines in marginal areas have seen little passenger traffic since their opening, prompting Menghe Railways to halt new construction projects until the current in-progress routes are completed. This is partly because air travel is more competitive at these distances; the 3,808-kilometer route from Baekjin to Ban Xoang costs ₩14,982 ($662.04) for a first-class sleeper and takes 14 hours to cover the full route when stops are included. Short-distance routes, however, successfully out-compete air travel, with lower fares, faster boarding times, and only a slight reduction in travel time. A high-speed train from Donggyŏng to Dongrŭng costs just ₩290 ($12.81) with a second-class seat and covers 141 kilometers in under 40 minutes, including a 5-minute stop in Taean. Combined with stops in some minor cities and good mass transit connections in major ones, this makes the east-coast route usable for commuter travel.

Passenger transport

Passenger trains in Menghe are divided into eight types based on speed and route, plus the special category of tourist trains. These range from the 300-kilometer-per-hour G trains which run on the high-speed network to single-car railbuses which serve rural lines in the east. In 2019, Menghe Railways recorded 1.467 billion passenger trips covering 490 billion passenger-kilometers, a figure which includes suburban commuter rail (To trains) but excludes urban rapid transit (D trains).

As on the high-speed network, passenger fares are relatively low, partly to encourage train over car travel and partly because average incomes in Menghe are lower than in developed countries. Electronic fare integration, however, is relatively advanced: in addition to the Menghe Railways smartcard and app, passengers can also swipe into trains with the OneStop smartcard and app. In addition to working on Menghe Railways trains, OneStop can also be used on rapid transit and bus systems in all major Menghean cities. Both card-app systems can be used to substitute for a ticket purchased online for Tier I and II trains; on Tier II and Tier III trains, a passenger can swipe on to the train at one station and swipe off at another, with the fare calculated and deducted automatically.

Menghe's large passenger stations are also considered world-class, particularly the new stations built according to architect Im Do-yŏn's design principles. These principles include spacious, well-lit waiting halls, separation of waiting spaces from platforms, and bridges and hallways which are laid out for the smoothest possible flow of large crowds. Large stations are also built to support the annual Lunar New Year migration, in which more than a hundred million people travel around the country to spend the Spring Festival with their families.

| Tier | Letter | Menghean name | Translation | Speed (1435mm) | Speed (914mm) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tier I | G (高) | 고속 여객 렬차 / 高速旅客列車 Gosok Yŏgaek Ryŏlcha |

High-speed train | 300-350 km/h | N/A | Direct service between major urban centers on dedicated high-speed track. |

| K (快) | 쾌속 여객 렬차 / 快速旅客列車 Kwaesok Yŏgaek Ryŏlcha |

Fast express train | 200-250 km/h | N/A | Direct service between major urban centers on tracks upgraded for increased speeds. They sometimes run on dedicated express track. Includes trains that exclusively run between two cities, e.g. the Sangha-Hwasŏng fast express. | |

| Tier II | J (直) | 직통 여객 렬차 / 直通旅客列車 Jiktong Yŏgaek Ryŏlcha |

Express train | 160 km/h | 120 km/h | Direct service between urban centers at standard or slightly increased speeds. |

| Tŭ (特) | 특급 여객 렬차 / 特急旅客列車 Tŭkgŭb Yŏgaek Ryŏlcha |

Limited express train | 140 km/h | 120 km/h | Limited-stop service between major urban centers, usually stopping at edge cities, county-level cities, and rural transfer hubs. | |

| W (緩) | 완행 여객 렬차 / 緩行旅客列車 Wanhaeng Yŏgaek Ryŏlcha |

Stopping train | 120 km/h | 100 km/h | Regional rail which stops at all stations along a route. Usually covers a long route in a rural or rural-urban area. | |

| Tier III | To (通) | 통근 여객 렬차 / 通勤旅客列車 Tonggŭn Yŏgaek Ryŏlcha |

Commuter train | 120 km/h | 100 km/h | Stops at all stations on the suburban portion of the route, but only stops at major transfer stations within the urban center. |

| D (都) | 도시 여객 렬차 / 都市旅客列車 Dosi Yŏgaek Ryŏlcha |

Metrotrain | 100 km/h | 80 km/h | Classification for urban rapid transit which is controlled by Menghe Railways rather than the municipal rapid transit corporation, usually because it runs on the national railway network. | |

| Ch (車) | 궤도공교차 / 軌道公交車 Gwedo Gonggyocha |

Rail bus | 120 km/h | 80 km/h | Railbus or railcar trains (sometimes multiple units) on rural or suburban routes with low passenger traffic. Not to be confused with trams, which are operated by the municipal government. | |

| Tier IV | Y (旅) | 여행 렬차 / 旅行列車 Yŏhaeng Ryŏlcha |

Tourist train | varies | varies | Trains for dedicated tourist service. |

Freight transport

Because many of Menghe's export processing zones are close to the coast, where they can be shipped by sea, railroads account for a smaller proportion of Menghean freight shipment than one might expect. Official statistics show that in 2019, 11.2% of Menghean freight tonnage was shipped by rail. Despite the low usage of freight rail service, the Railway Regulatory Authority has encouraged Menghe Railways to expand freight service, in the hopes of reducing traffic on roads and pollution from heavy lorries. It is also hoped that refurbishment of the Trans-Dzhungestan Railway will create demand for international rail freight.

Ton per ton, a majority of Menghean rail freight is bulk cargo, which accounted for 53.8% of rail tonnage in 2019. A majority of this bulk cargo is coal, which is shipped from large inland mines and deposits to power plants and factories in the central region and coast. Metal ores are the next most common type of bulk cargo, followed by grain and fertilizer. Container traffic accounts for 5.9% of rail freight.

To allow the use of Form M "CargoMax" railcars, most freight trains in Menghe travel on non-electrified rails, as overhead wires would not leave space for double-stack container cars and other oversize cargo. This has the advantage of separating long, slow freight trains from most passenger traffic, allowing the use of faster passenger trains on electrified lines. Conversely, it also means that Menghe has invested little effort in purchasing or developing powerful electric freight locomotives.

Military transport

In addition to its civilian service, Menghe's rail network has a number of strategic military roles. One is to move supplies, military vehicles, and heavy weapons to the front line in the event of a war. As part of its duty as a "mixed-motive state-owned enterprise," Menghe Railways must comply with requests from the MoND to support the armed forces' personnel and freight needs, even when these services are not profitable. A prime example is the dense network of freight tracks in the southwest. Built in a relatively poor and sparsely populated area of the country, lines see very little civilian passenger and freight traffic, but they are crucial to supplying the front lines in any war against Maverica.

The CargoMax and Extra Wide loading gauges were specifically chosen to allow main battle tanks with a width of up to 3.7 meters to safely move on flatcars at this gauge. In addition to moving reinforcements, military trains also move heavy vehicles from their bases to exercises, from factories to bases, and from bases to the capital city during the annual Victory Day parade.

Menghe's conscription policy means that twice a year, in the span of a few days, close to 500,000 new recruits have to report to training bases scattered across the country's inland region. During the biannual conscript summoning periods, many trains run with extra carriages, or with temporary (imsi) passenger trains added to the schedule. If troops in the Mobilization Reserve were called up for service, Menghe Railways would bring an even larger number of temporary military trains into service to move them.

Per national regulations, military freight and military personnel travel free of charge on Menghe Railways, provided that they are moving due to military orders. Menghe Railways can, however, seek reimbursement for these trips from the Ministry of Transportation. Thus, the cost of moving military personnel and freight by rail appears under the budget of the Ministry of Transportation rather than the military budget.

Standards and regulations

Track gauges

During the late 19th century, Menghe's rail network contained seven different types of track gauge, the result of political fragmentation and privatized construction. Of these types, 1435mm, 1000mm, and 914mm were the most common, with the latter two concentrated in specific regions. Following the rationalization of the rail network in the late 1960s, the number of gauges was reduced to two: 1435mm and 914mm.

Of the two gauges in service, 1435mm is the most common. This is the gauge used by all rail traffic outside the east coast, as well as new freight and intercity lines within the east coast region. All high-speed trains in Menghe use 1435mm gauge. Because this gauge is shared with Polvokia, Themiclesia, Dzhungestan, Dayashina (high-speed only), and, after re-gauging, Argentstan and the Republic of Innominada, it allows for convenient international transportation.

Narrow-gauge 914mm is exclusively found in the eastern region of the country, specifically the provinces of Central Donghae, South Donghae, Ryonggok, and Unsan, as well as Donggyŏng directly-governed city. This track gauge was first adopted by the State of Sinyi, and later used by the privately-run Donghae Railways, earning it the name "Donghae gauge." Like other narrow-gauge railways, it allows for smaller tunnels, narrower bridges, and a lighter track bed, which are useful features in Eastern Menghe's rugged terrain. Construction of new 914mm gauge branch lines continued until well into the 2010s.

Some tracks in eastern Menghe use a dual gauge layout, with the outer rails spaced at 1435mm and a central rail spaced 914mm from one of them. At stations, both trains share the rail adjacent to the platform, though on some routes the narrow-gauge train switches to the inner rail in between stations.

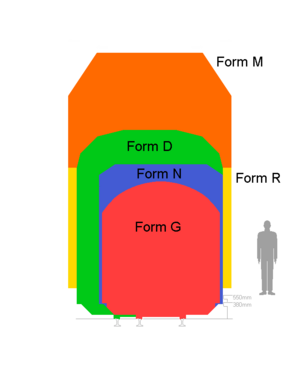

Loading gauges

There are six standard loading gauges on Menghe's national railway network, up from three following standardization in 1965. The loading gauges are labeled alphabetically with letters of the Menghean Sinmun alphabet, i.e. G, N, D, R, M, and B. These loading gauges are set by the Railroad Regulatory Agency, which keeps a centralized record of which loading gauge each track can support.

- Form G ("Donghae legacy")

- Form G was devised to fit the narrowest tunnels, platforms, and obstacles on the pre-existing 914mm Donghae Railways network. With a maximum height of 3200mm, a maximum width of 2750mm, and a highly curved roof, it is the smallest Menghean loading gauge, and it cannot transport intermodal containers as the corners would protrude.

- Form N ("Donghae improved")

- Form N was devised to offer the maximum possible width and straight-side height which would fit on dual-gauge track with Form D. That is, when a Form D and a Form N train are both using the left rail, they will protrude the same distance to the left. This became the new standard loading gauge for all 914mm track laid after 1965. It can carry both standard-height and Hi-Cube intermodal containers.

- Form D ("Federal")

- This loading gauge is based on the standard dimensions used on by Federal Railways in the early 20th century and built into Menghe's western rail network. With a height of 4400mm above the rails, it is tall enough to run bilevel cars, though this requires lowering the bottom level's floor below the 550mm platform height. As mentioned above, Form D trains are able to use platforms built for Form N trains, when sharing the platform-side rail.

- Form R ("Extra wide")

- This is a modified version of the Form D loading gauge. It differs only in that it allows a protrusion of 200mm from each side of the Form D template, for a total width of 3800mm. This loading gauge was originally developed to transport JCh-5 main battle tanks, which were too wide for Form D flatcars. Due to the dimensional restrictions on the overhang space, Form R cars can safely travel past 550mm platforms, as long as there are no fences, signs, or other objects above the platform floor.

- Form M ("CargoMax")

- This loading gauge was introduced in 1995, as Menghe's rapid economic growth accelerated. It allows for the use of double-stack container cars, with either a low flatcar or a well car. When a well car is used, it is possible to load a Hi-Cube container on the top position. Unfortunately, because CargoMax trains require a maximum height of 6200mm above the rail, they cannot travel under live overhead wires while maintaining a safe buffer zone. They also require larger tunnels and higher bridges than Form D and Form R trains. As such, most railway track in Menghe has been either electrified or approved for Form M use, with separate Federal and CargoMax tracks linking cities.

- Form B ("High speed")

- This loading gauge was inherited from Themiclesia, after Menghe purchased 700 Series high-speed trains for use on its network. It has the same width as Form D, but differs in having a squared-off top (for aerodynamic guard structures around the pantographs) and slightly different dimensions at the base. Form D trains are able to use Form B approved track, but the reverse is not always true.

Platform heights

There are three standard platform heights in use on Menghe Railways's network: 380mm, 550mm, and 1250mm. Other platform heights existed in the early 20th century, especially on private lines with non-standard track gauges, but all have been rebuilt to one of these standards or removed from use.

- 380mm platform

- This was the original standard used by the State of Sinyi in 1875. It was widely built in eastern Menghe during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, due to its low cost and the low height of Donghae Railways's passenger cars. This platform height is no longer used in new construction, but it is still present on some rural routes in the east, especially those using Form G loading gauge.

- 550mm platform

- This was the original standard used by the State of Namyang in 1871, and it became widespread under the Greater Menghean Empire. In 1965, the Ministry of Railways required that all new standard-gauge platforms be built to a height of 550mm, and required that all new rolling stock have a 550mm floor height at the entrance. Some 380mm platforms were also rebuilt to a height of 550mm, especially on platforms serving dual-gauge track.

- 1250mm platform

- This platform height was first bought into use in the 2000s, when Menghe built its first high-speed rail line. Because the Themiclesian high-speed trains sold as part of the project had 1250mm floors, it was necessary to build new platforms to this height to accommodate them. Because high-speed trains had separate platforms from other passenger trains, this was not an issue. Since the early 2010s, Menghean fast intercity trains (K type) have also used this platform height.

While trains with 1250mm floors run routes with exclusively 1250mm platforms, there are a number of routes in the eastern part of the country where a train with a 550mm floor serves both 550mm and 380mm platforms. The Ministry of Railroads rationalization committee concluded that the 170mm (6.7-inch) difference, about the height of a stair step, was small enough for passengers to board the train without difficulty, and did not require 380mm platforms to be raised unless it was part of a larger station overhaul. The vertical gap does, however, make these platforms inaccessible for passengers with wheelchairs or other mobility constraints. This problem has become particularly acute in recent years, as Menghe's narrowing demographic pyramid and its high rural-urban youth migration have contributed to a growing share of elderly in the population in the rural areas served by 380mm stations.

Beginning in the late 2010s, some elderly rights groups have lobbied the Ministry of Transportation to eliminate the vertical gap, either by raising the remaining 380mm platforms or by purchasing rolling stock with a ramp or elevator mechanism. Opponents of changing the regulation have pointed to the high expense of these measures, especially given the low and declining ridership on the remaining 380mm platform routes and the possibility that Menghe Railways will eliminate service to some of them in the next decade. As of June 2020, the Ministry of Transportation is still conducting feasibility studies of these options, and while some new trains slated for delivery in 2021 will feature a wheelchair-elevator car for trial service, there are no plans to make these features mandatory.

Coupling

Early Menghean trains used buffer and chain couplers, which remained in production for new rolling stock into the 1960s. Following the Menghean War of Liberation, the Menghean government sought to upgrade its new trains with semi-automatic couplers to allow faster and safer coupling. Because of its close relations with Kolodoria, Menghe adopted the SA3 coupler, which was installed on all new rolling stock and retrofitted to some older locomotives and cars.

Recently, Menghe has begun transitioning to the C-AKv coupler. This design is mechanically compatible with the SA3 coupler on existing rolling stock, but it also features built-in, automatically-connecting plugs for electric power and pneumatic brake lines.

Menghean EMU trains, including urban rapid transit trains, W2 stopping trains, commuter trains, and G and K class high speed trains, use Scharfenberg couplers, with a national standard for the coupler's height above the track and the placement of the electrical and pneumatic connections. Because it cannot bear heavy loads, the Scharfenberg coupler is not used on freight trains, and there are no plans in Menghe to adopt it on other types of passenger train.

Electrification

Menghean railway electrification systems are also based on Kolodorian standards, with a 3 kV DC overhead line hung from a tensioned catenary system over the track. The 3 kV DC system, however, only applies to non-high-speed routes. High-speed (G) track uses a 25 kV AC overhead wire at 50 Hz, as the first trains and overhead wires were purchased off-the-shelf from Themiclesia. Because Menghean high-speed trains run on dedicated track and have separate platforms at stations, the use of incompatible voltages is not a serious issue, though it does require special planning to ensure that parallel and intersecting routes do not generate electrical interference. A few K-type fast express routes use multi-system trains capable of running on both 3 kV DC and 25 kV DC at 50 Hz.

Menghean safety standards require a clearance of at least 400mm between the train roof and charged electric wires; thus, trains with the "Federal" Form D loading gauge rely on an overhead line with a minimum height of 4,800mm above the track, though the maximum height can run as high as 6400mm for slow-moving trai. This allows Form M ("CargoMax") oversize carriages to pass under the wires, but only when the power to that section is shut off, which is sometimes necessary where two tracks cross. The average height of the overhead wire sits at 5800-6000mm for most sections of track, and at 5300mm for high-speed track.

Because the powered overhead line is supported by a catenary wire, additional clearance may be needed when determining the structure gauge for tunnels and bridges. The electrification of the '20s-vintage Jindong tunnel, for example, required a special mounting system to attach the tensioned wires to the tunnel roof.

Notably, railway electrification in Menghe only serves trains with a track gauge of 1435mm. All narrow-gauge (914mm) trains must use some other form of power. This is because the overhead wires are too far above the track to allow a reasonably-sized pantograph to draw electricity from them, and because narrow-gauge trains are not centered on dual-gauge track, requiring a special pantograph design. Narrow-gauge trains must also pass through tunnels with a very low structure gauge, making electrification difficult. The use of dual-gauge track also rules out a third rail system, as depending on the stretch of track, the narrow-gauge train is either using the left rail, using the right rail, moving between the two, or, in some cases, running in the center. As such, narrow-gauge routes typically use diesel propulsion, either in the form of a diesel locomotive, a diesel railcar design, or a diesel multiple unit.

Menghe Railways is also experimenting with battery electric multiple units on some narrow-gauge routes, though their reduced power-to-weight ratio, 300-kilometer range, high cost, and long charging time at specially designed stations all represent severe problems on Menghe's narrow-gauge rural tracks.

Cross-border connections

Menghe has a number of cross-border rail connections with neighboring countries, though not all of them are currently operational. The list below covers Menghe's neighbors in clockwise order, starting in the south.

Altagracia

The Sunju-Altagracia Railway was one of Menghe's first railroads, built during the Three States Period by the Namyang Government. It also holds the record for the largest number of gauge changes. It was originally built by a Sylvan company in 1668mm gauge, and expanded to connect to Pyŏng'an and Giju. Between 1931 and 1932, the Greater Menghean Empire re-gauged the Bonggye-Pyŏng'an section in 1435mm gauge. After the fall of Altagracia, the remaining section between Sunju and Altagracia was re-gauged, as was all non-tram track on the Altagracian peninsula itself. Following Menghe's defeat in the Pan-Septentrion War, Sylva re-gauged the Sunju-Altagracia segment back to 1668mm to support Sylvan rolling stock; after the Communist victory in the Menghean War of Liberation, the DPRM re-gauged the line back to 1435mm all the way to Bonggye-ri. During the 1990s, the Sunju-Bonggye section was converted to dual-gauge 1435mm and 1668mm track to allow direct travel between Altagracia and Sunju without disrupting travel via Giju on the standard-gauge mainline. During the Innominadan Crisis, however, Menghe cut off all travel across Altagracia's land border in protest against Sylva's aggressive conduct and its refusal to negotiate on Altagracia's status. As symbolic measures to back up this stance, Menghe Railways stripped away the 1668mm third running rail on the former dual-gauge track, and the Menghean Army used explosives to blow a gap in the final 1668mm segment approaching the border.

Argentstan

Menghe has four railroads which cross the border to Argentstan, though two of them use the same port of entry facility in Ban Xoang. One of the two Ban Xoang border crossings is part of the South Sea High-Speed Route, a high-speed rail line which links Argentstan's two main cities to the Menghean high-speed rail network (and, by extension, to Polvokia). The other is a single-tracked, non-electrified route. A third rail link, this one double-tracked, runs throuugh the northwest corner of Viengkham Prefecture, and was built between 2016 and 2018. The fourth rail link is in Samtay, and is also double-tracked and non-electrified, though it sees a greater volume of regular service.

Menghe invested a great deal of resources in building up its road and rail links to Argentstan (then part of the People's Republic of Innominada) after invading the territory in 2014 during the Innominadan Crisis. Rail links were seen as especially important for moving large volumes of military equipment into Altagracia, as a Maverican attack aimed at the opposing coast could cut off the Menghe-Innominada supply route if successful. As part of this logistics-streamlining effort, all national railroads in Argentstan and the People's Republic of Innominada were re-gauged from 1668mm to 1435mm, and local rolling stock was re-gauged to fit them. Following the completion of the gauge-change effort, there is no longer a break of gauge at the Menghe-Argentstan (formerly Menghe-Innominadan) border.

People's Republic of Innominada

There is a lone, non-electrified, single-tracked railroad running through Kenethau Prefecture to Menghe's 61-kilometer border with the People's Republic of Innominada. This stretch of railroad was built during the Pan-Septentrion War to supply the advancing Imperial Menghean Army in Maverica, and it saw some freight service in the postwar era. Since 2004, it has been closed to civilian traffic and the port of entry at its northern end is abandoned. Menghe Railways conducts the bare minimum maintenance required to keep the line usable for shipping supplies and armored vehicles.

Maverica

Menghe has three railroad connections with Maverica, all of them single-tracked and all of them built during the Pan-Septentrion War. During the 1950s, the section which connects to Hasavyurt was briefly part of the Trans-Hemithean Railway with service from Sunju to Kien-k'ang. Freight service kept these routes open during the time of the DPRM's socialist alliance with Maverica, and into the 1990s, but after the breakdown of Menghe-Maverican relations in 2005, these border crossings were closed to regular traffic. Like the lone rail link to the People's Republic of Innominada, they are today used almost expressly to support Army units on the highly militarized border.

Dzhungestan

Menghe has four railroad connections with Dzhungestan. One is a double-tracked, non-electrified route from Suhait to Dörözamyn, which was built and expanded during the Pan-Septentrion War as part of the Central Hemithean Railway. The other two low-speed lines are single-tracked, and run to Khazaarkhot (in the south) and Höryynbataar (in the north). Because of Dzhungestan's small population and low incomes, passenger service on these lines runs relatively infrequently and sees a limited travel volume, though from 2010 onward Menghean cross-border migrant workers have begun moving to Dzhungestan to train to manage mining operations. Most traffic on these rail links comes in the form of freight, especially ore and lumber, which are in high demand in Menghe's industrial economy. To improve the flow of resources, Menghe has invested heavily in improving rail links to new and existing mines in Dzhungestan, as part of its "Northern Road" regional infrastructure initiative.

A portion of the Trans-Hemithea High-Speed Railway also runs between Suhait and Dörözamyn, on separate track from the low-speed route. To encourage thru travel, passengers on the THHSR do not have to pass through customs when their train crosses the border, only when they disembark at their final destination. Trains on the other routes must pass through customs checks at joint Menghean-Dzhungestani border facilities.

Polvokia

Working west to east, there are five railroads which cross the border between Menghe and Polvokia. The first is a single-tracked, non-electrified line in Gokhap Prefecture; the second, a double-tracked bridge in Myŏngjin; and the remaining three cross the border at Baekjin, and consist of a single-tracked freight bridge, a double-tracked electrified passenger bridge, and a double-tracked high-speed bridge, also part of the Trans-Hemithean High-Speed Railway.

During the early 20th century, Polvokia adopted 5 foot 6 inch (1676mm) gauge, one of the widest broad gauge options in use at the time. Foreign engineers believed that this would make for a more stable sleeper bed on sections of track running through seasonally freezing and melting mud, and it also allowed the use of larger and heavier locomotives, better suited to pulling heavy cargo and ore trains or pushing snow plows over the track. As a result, all of Polvokia's standard-speed border crossings with Menghe include a break of gauge. The high-speed route is the one exception, as it was built in 1435mm gauge for its entire course in Polvokia. Because it used new-build, high-speed-only track, this did not create compatibility issues for Polvokia.

At all of the other routes, trains crossing the border must pass through a special transfer facility. The westernmost transfer facility is on Polvokian facility, while at the three remaining crossings, Polvokian broad-gauge track crosses into Menghe over a bridge but immediately diverts into a rail yard after the bridge ends. Originally, transferring passengers and freight at these facilities was a time-consuming process, but the containerization of freight and the development of bogie exchange rolling stock sped up the process. On the Menghean side of the Baekjin passenger bridge, there is even an automated gauge change mechanism, allowing trains with variable gauge wheelsets to cross between narrow and broad gauge sections without stopping (though the train must reduce speed when passing over the mechanism). A similar facility was added to the Myŏngjin crossing, but only for lighter passenger trains. Along with the electrification of the Baekjin-Yŏjin and Baekjin-Ryŏngdo routes, and rising incomes in both countries, these changes have increased the flow of passenger traffic between Menghe and Polvokia.

Menghe's rail links with Polvokia provided a strategic source of coal, lumber, and grain during the Pan-Septentrion War, and also supplied Menghean Communist forces during the late phase of the Menghean War of Liberation. For the DPRM, they represented a strategic source of resources, and the flow of goods on these railroads has continued through the Menghean economic miracle. As in Dzhungestan, Menghe has invested heavily in Polvokian infrastructure as part of its Northern Road campaign, linking more remote factories and mines to the rail network. On average, these changes have increased rail traffic, but some projects - like the building of new oil pipelines and tanker loading sites - have reduced it.