Gentlemen (Themiclesia)

The Gentlemen (郎中, rang-trjung) are retainers of the monarch of Themiclesia and form a broad category of officials managing affairs tangent to the crown. Their original duties including protecting and accompanying the monarch, but subsequently they extended into several government departments. Their elective nature has been connected with the later development of Themiclesian democracy. First entering historical record around 100 BCE, they are by some regarded as one of the oldest military units in Themiclesia and Septentrion in general. Their leader is the Gentlemen-Marshal. As a guard of honour, they are now unusual in that they do not undergo military training.

Name and translation

The word rang (郎) is a graphical variant of the character 良, which in Menghean oracle script is a pictograph of a tunnel leading into a semi-underground dwelling, whence its meaning of "hallway". Since 良 is now borrowed according to the rebus principle to mean "good", an additional component varies it to produce 郎. The term rang-trjung means "[those] in the hallway, corridor".

Their name was translated as "gentlemen at arms", after Tyrannian practice, because Casaterran diplomats first noticed their most visible function, standing guard at the gates of the palace hall; however, this function (see below) has become one of a peripheral relevance for centuries.

History

Menghean sources

The provenance of the Gentlemen-at-Arms is ancient. During the Warring States Period of Menghe (7th to 3rd c. BCE), rulers typically resided in halls situated on elevated daises, with a peristyle around the edges thereof and terraces on its walls. Gates, flanked by terraces, were located on these corridors; these were a vital point of communication. The Gentlemen-at-Arms originated as cadets of the nobility, serving as retinue. With the unification of Menghe by the Meng Dynasty in the 3rd c. BCE, martial prowess became secondary to other talents. During this time, the Gentlemen-at-Arms not only provided protection but company as well, probably in competition with other retainers. These officials, serving the monarch directly, were distinguished statutorily from those in the bureaucracy. The former were called the retinue or servants (宦, ghwranh), and the latter officials (吏, rjegh).

Pre-dynastic Themiclesia

Themiclesian history provides fragmentary accounts of the early monarchs' retinues, prior to unification under the Tsjinh Dynasty (265 – 421). It is assumed that the more important states have imitated the political structure of the Meng State, though specifics are controversial. Bronze inscriptions, which were productive in Themiclesia after obsolescence in Menghe, demonstrated that Gentlemen-at-Arms existed in the Tsjinh State and the Kem State; whether this is a copy of one from another, or both directly are imitations of Menghean analogues, is not clear.

Dynastic Themiclesia

The unification of Themiclesia with the assistance of G′wjang Lus in the 260s lead to radical changes in its the political structure. Ghwjang himself possessed considerable knowledge of Meng Dynasty administration. His reforms brought Themiclesia's own government closer in line with that of Menghe by introducing a dedicated government council to centralize administration over the palatine states and a reinforced royal guard, based on militia levy. Since the gentlemen at arms were no longer the first line of defence against physical threats to the monarch, their military function gradually deprecated, encouraging their number to participate in the bureaucracy. Originally, this was clerical work, but proximity to the crown and familiarity to the procedures of government allowed their administrative functions to come to the fore.

It has been suggested that the Gentlemen-at-Arms of Themiclesia were originally hostages of vassal clans serving at the ruler's court. This view is challenged in that there is no explanation for placing individuals, from clans hostile or untrusted as to require taking hostages, in a position over the ruler's safety. Nevertheless, by the period immediately before G′jwang Lus' time, they were instead voluntarily sent by regional clans to serve the ruler, who had sufficient authority his favours were a worthwhile pursuit. Being a Gentleman-at-Arms was a financially unprofitable (for some, ruinous) activity: one paid for one's own armour, weapons, and mount, and those in higher ranks had to pay for chariots' maintenance. Yet it was an alluring opportunity for those who desired advancement and were unwilling to rise through normal clerical work.

While being a gentleman at court provided political possibilities in the Tsjinh court, that its members were not remunerated but charged for their service effectively limited these possibilities to the elite, most of whom were already invovled in public service. The gentlemen were a key institution in the reproduction of the elites, since successful bureaucrats could place their offsprings into the gentlemen at arms, where they enjoyed a considerable advantage over commoners who joined the bureaucracy. However, service did not guarantee to later success; the gentlemen were consistently assessed by superiors and peers for their character and abilities, and only those qualified acquired desirable appointments with better potential.

Some historians conclude that the gentlemen at arms, as an institution, combined both meritocratic and aristocratic elements. For the former, it discerned and nurtured talent, and for the latter, it gave privilege and opportunity to the elites to participate in a centralized government. The gentlemen at arms thus became a bonding, stablizing force between the monarchy and aristocracy, serving the interests of both and supporting a lasting, stable form of government.

Role

Bodyguards

Today, Gentlemen-at-Arms, as bodyguards, are purely ceremonial. It has been argued that their function as bodyguards has been marginal since the 4th or 5th centuries, and that their use of bronze arms demonstrates as much, though not all of their armoury is bronze. As opposed to the Royal Guards, who have consistently been armed with fit technology. However, in spite of evolution of the institution, they are still mustered every day and follow the sovereign. They are also stationed at the Gates of Rectitude, Thousand Autumns, and Myriad Springs, symbolically ensuring that the entrants are not armed.

Future civil servants

Though deprecated as a military force, their proximity to the throne and unique recruitment method has permitted them to retain an identity quite as long-lasting as major political institutions. Out of Themiclesia's prefectures, about 150 to 200 Gentlemen-at-Arms would be produced simultaneously to the members of the Protonotaries every three years. It is customary for Gentlemen-at-Arms, if they failed to acquire the largess of a government minister or similarly powerful figure during their six-year terms of service, to be appointed to minor positions in the civil service when that expires. A typical appointment is as a county's sheriff or alderman, at the very bottom of the civil service hierarchy. From this position, it is possible to work upwards, though successful ex-Gentlemen-at-Arms are few and far-between. As it was typical for regional clans to posit two or three candidates each triennial recruitment season, those that did not make it as Protonotary or Secretary to the Council were viewed their service as duty of the gentry and a necessary sacrifice; this did not stop them from complaining of poor salaries and prospect.

Courtiers

During their terms of service, the king (or emperor after 542) was at liberty to appoint his Gentlemen-at-Arms to certain position mostly at his discretion. One of the main ways for Gentlemen-at-Arms to acquire more influence was to be appointed as an official of the royal household, which at the time boasted a variety of offices that barely was second to the bureacracy. Commensurate positions also existed in serving the empress and the emperor's concubines. As retinue, however, they are junior to the Privy Council and Council of Peers.

Diplomats

Themiclesian diplomatic practice required the initial envoy sent to any polity to be of the 2,000-bushel grade in the civil service, so that more power and gravity of office could persuade the foreign state of Themiclesia's sincerity and willingness to negotiate. After their friendly intentions have been ascertained, however, lesser officials could be sent when no negotiation is required, only transmitting information. During the 5th through 14th centuries, gentlemen-at-arms have fulfilled these minor diplomatic offices and usually formed an ambassador's guards. Despite the assignment, they were still expected to perform diplomatic duties at the ambassador's direction. After the 14th century, the protection of diplomatic missions devolved to the Colonial Army in Columbia and Meridia and to the Marines in Meridia and Casaterra after 1325, when Themiclesia's market colony of Portcullia was taken by the Yi dynasty of Menghe. While no longer functioning as bodyguards, gentlemen-at-arms still remained as advisors to ambassadors. When consulates were established in the 18th century, they were usually filled by gentlemen-at-arms. The opportunity to see diplomacy in action was an important attraction to aristocratic enlistment with the gentlemen-at-arms.

Divisions

There are several groups of Gentlemen depending on the figure whom or place where they serve. When used alone, "Gentlemen" usually refers to the sovereign's retainers. When there is a empress or empress-dowager, their gentlemen usually take their mistresses' residences as a prefix to their titles. Due to their historic relationship with the monarch, gentlemen have been assigned to serve to various government departments. In many cases, they have become officials more closely connected to the department they service than the monarchy, taking on duties that other gentlemen cannot perform.

- Gentlemen of the Front Hall

- Gentlemen-in-Waiting

- Cavalry-Gentlemen

- Gentlemen of the Privy Council

- Gentlemen of the House of Commons

- Gentlemen of the Kaw-men Hall (in service to the House of Lords)

- Gentlemen of the Court Hall

- Gentlemen of the Middle Palace (in service to the Empress-consort)

- Gentlemen of the Gweng-l′junh Palace

- Gentlemen of the Gwreng-ngjarh Palace

- Gentlemen of the Chancery (in service to the Cabinet Office)

Front Hall

The Gentlemen of the Front Hall (前殿郎中) are so named because they flank the Front Hall, in the Sk'ên'-ljang Palace, whenever it is in use. However, ceremonies at the Front Hall have decreased in importance since the 14th century, so the Gentlemen serving there have generally become officials of the royal household or members of the Privy Treasury's staff.

Gentlemen-in-Waiting

The Gentlemen-in-Waiting (寺郎中) form the retinue of the sovereign. Formerly, around 30 to 50 would have filled this position, but following the Pan-Septentrion War their numbers have fallen to between 10 and 20. These officials today reside at the palace and work in shifts for the sovereign.

Cavalry-Gentlemen

The Cavalry-Gentlemen (郎中騎) are the sole remaining militarized portion of the Gentlemen. Their tasks are to follow the monarch on horseback whenever he leaves the royal palace.

Privy Council

There are a number of gentlemen (給事中郎中) who are active in the Privy Council.

House of Commons

There are two distinct kinds of retainers in the House of Commons, both translated as "gentlemen" into Anglian. The first is the Gentlemen of the House (省郎中), who were originally the monarch's retainers that have been assigned duties at the House. These individuals today are the House's senior clerks who certify bills to the House of Lords, oversee the archival of original manuscript of laws, and sends the House's orders to other government agencies. These are now appointed by the House from a pool of legal professionals.

The second kind are the retainers of the members themselves (省舍人), whom the members appoint officially as their pages or valets and reside with the members themselves. Members' retainers are not public servants and have private compensation arrangements with their employers. Often, retainers are completely unpaid, offering their services for future favours, contacts, and experience in managing a legislator or (in select cases) minister's afairs. At one point, it was commonplace for aspiring politicians, from a more modest background, to begin their political careers as retainers to serving members. The Valet's Wing in the House of Commons complex is named for the place where these individuals stayed while the House sat.

House of Lords

The gentlemen of the House of Lords serve similar functions as those of the House of Commons, but there are fewer of them as certain analogous positions must be filled with peers rather than the monarch's retainers, who are usually commoners.

Council of Correspondence

One of the most important assignments the sovereign's retainers can obtain is in the Council of Correspondence, which became the chief administrative body of Themiclesia in the 6th and 7th centuries. These officials served under the secretaries of state, initially as copyists and clerks, but they eventually became advisors or assistants. By the 8th century, they were divided into bureaux overseen by the secretaries of state, as the Council's jurisdiction and secretaries' portfolios solidified.

How the gentlemen were assigned to portfolios in the Council depended on their relationship with prominent administrators and nobles. An active monarch may prefer to appoint his retainers whom he knows to have specific talents or connections to an appropriate position, but in other cases it seems the appointed secretary of state has the privilege of nominating his assistants from a pool of candidates the monarch believes is ready for serious political duties. The assignment to the Council is not only prestigious but also difficult to obtain; less talented gentlemen usually found themselves as a county's sheriff or in other minor offices. Despite this intimacy with the central administration, it was generally not possible for ministers' assistants to be promoted to ministerial office directly, as this violated the progression in civil service rank.

In modern Themiclesian, junior ministers are still called "gentlemen" in reference to this old practice.

Middle Palace

Gweng–l′junh Palace

Gwreng–ngjarh Palace

Chancery

Ranks

| Position | Salary | Class | Rank | Typical title | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gentleman Marshal | 郎中令 | 2000 | III | 13 | Counsel |

| Gentleman Secretary | 郎中丞 | 600 | VI | 10 | Officer |

| Chief Usher | 大謁者 | 1000 | IV | 10 | Officer |

| Gentleman Captain | 郎中司馬 | 800 | VII | 8 | Officer |

| Captain of Gentlemen-in-waiting | 侍郎中司馬 | 800 | VII | 8 | Officer |

| Gentleman Falconer | 郎中左弋 | 600 | VIII | 5 | |

| Gentleman Hunter | 郎中左田 | 600 | VIII | 5 | |

| Gentlemen of Protonotaries | 中書郎中 | 500 | VII | 6 | |

| Gentlemen of Correspondence | 尚書郎中 | 600 | VI | 7 | |

| Gentlemen of Peers | 門下郎中 | 500 | VII | 6 | |

| Gentlemen of the Privy Council | 中大夫郎中 | 500 | IX | 6 | |

| Gentlemen of the Chancery | 府郎中 | 400 | IX | 2 | |

| Gentleman Treasurer | 郎中廷府 | 500 | IX | 2 | |

| Gentelmen Cavalry | 郎中從騎 | 300 | 1 | ||

| Gentlemen | 郎中 | 250 | 1 | ||

Recruitment

Entitlement

Any bureaucrat who attained to the rank of 2,000 bushels could furnish one of his sons or junior relative (蔭) within five generations as gentleman. This could be done only once by the bureaucrat in his career.

Donation

Aside from triennial civil elections and entitlement, it was possible to enter through donation (貲). While entitlement allowed a senior bureaucrat to enter one of his sons, he had to donate if any of his other sons wished to join the gentlemen at arms. This was also available to the lower-ranked bureaucrats or gentry living in the countryside, not currently in office. However, donation was only available to those who were already gentry; commoners without at least a token connection to gentry could not donate to obtain entry. It is estimated that a majority of the gentlemen, during the Tsjinh to Mrangh dynasties, actually bought their positions. Different prices existed for various positions according to the fashion of the day or potential of gaining the Emperor's attention. The first listing of prices are found in the Ran-lang Collection, which date to the 1st c. BCE. The prices of Gentlemen position at later points in time are also provided.

Election

The most highly-regarded way to enter was the civic election (選). Every three years, the gentry of a prefecture met before a returning officer, after candidates registered with him. The candidates then canvassed the gentlemen for their support. At the end of the election season, the returning officer summoned the gentry to the prefectural capital and asked them to rank the candidates from First Class to Ninth Class. Those ranked Second Class would be appointed to the civil service immediately, while those Third and Fourth Classes were selected as gentlemen at arms.[1]

Substitution

One son of a bureaucrat who died in public office was customarily appointed as gentleman at arms (繼), to continue his family's legacy in public service. This is provided the bureaucrat who died was himself eligible to be a gentleman at arms.

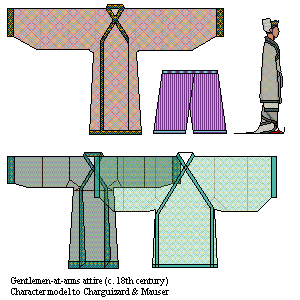

Uniforms

Traditional costumes

The gentlemen-at-arms have no uniforms such as understood in a modern, Western military context; however, there were and are still sartorial standards to which members of the body should adhere. Some characteristics of acceptable attire were defined by sumptuary laws, on which gentlemen-at-arms, unlike soldiers of other kinds, were highly positioned, while other characteristics were only fashionable.

Before 1847, most gentlemen-at-arms still dressed in the traditional costumes of robes. There was no stand number of layers, though three seems typical in summer and four or more in winter. The topmost layer, the over-robe or p′ru (袍), was invariably made of a light, semi-transparent fabric that showed the layer immediately beneath it; its colour varied with court positions and the seasons. On the summer and winter solstices, the courtiers wore yellow and black respectively, and the vernal and autumnal equinoxes blue and white. On other days, royal retainers like the gentlemen-at-arms wore crimson, while bureaucrats, lawyers, and accountants black. The over-robe, loosely tied about the wearer's body, had much excess room, which was supposed to give the wearer a floating appearance.

Under the p′ru was the single-robe or tan (單衣, tan-′jer). This garment had no standard colour or patterns, but the quantity of materials used were regulated. For the emperor, palatine princes, and peers, this was 7.2 drjang′ (丈) or 17.64 m of material; for other courtiers, it was 7 drjang′ or 17.15 m. From reconstructed models and excavated examples, the court robe was inevitably much taller and wider than the wearer: a usual example recovered from a 7th-century burial measures 2.54 m from collar to bottom rim and 3.02 m from one sleeve tip to the other tip. The robe usually wrapped around the wearer twice and formed a train behind him, even after allowances for drape over the sash. This formed the characteristic silhouette of Themiclesian civil servants' "uniforms" that many Casaterran visitors commented on.

Unlike the tan, which was always single-layered, the under-robe (中衣, trjung-′jer) could be quilted for warmth. Like the tan, this layer also has no standard colour or pattens but has regulated dimensions. Since the collars and bottom edge of this robe will peep out from under the tan robe, they are typically made with a colour that contrasts with the body of the garment that is kept plain for reasons of cost. For the emperor, princes, and peers, this robe consists of 5.4 drjang′ or 13.23 m of materials; for other courtiers like gentlemen-at-arms, it was 5 drjang′ or 12.25 m. The waist of this garment is cut a little higher than on the tan, forming a slightly longer train. This is to protect the tan from dragging on the ground; in turn, the trjung-′jer has resilient materials on the under-side for its own protection.

Unlike the robes, the hoses are virtually unregulated, most likely since the robes are long enough to obscure them. Themiclesian courtiers typically wore two layers of hoses for warmth. For footwear, wooden cleats were usual, but in most court events they would be wearing socks instead.

The primary indicators of position and rank are headwear, sash, and seal. Gentlemen-at-arms wear the "martial headwear" (武弁, mja-brjonh) that is typical of military officers up to the equivalent of a Western colonel. Until the middle of the 19th century, most Themiclesian men wore their hair in buns behind their heads; a cloth coif, the kjen (巾) was wrapped around the bun to keep hair from tangling with other parts of headwear. Then, the tsrêk (幘) or fillet was added. The fillet evolved out of soldiers' headband to keep hair from coming loose, which was apparently a hazard, or metal helmets from grazing against the forehead. This garment has subsequently rigidified and was expected from virtually all courtiers, since it also formed a firm foundation for a coronet, if wearing one.

Most gentlemen-at-arms have not yet earned the right to wear coronets while in this position; as such, they only wear a cloth covering over the fillet starched for a more sturdy appearance; the corners of this cap end in strings that may be tied under the wearer's chin. Captains of divisions are entitled to an one-arch tsjin-kin-korh, while the principal counsel responsible for the entire body wears one with two arches, both shared with commensurate ranks in the civil service. The same is true of the sash and seal: the sash will be grey, the lowest grade, for the vast majority of gentlemen-at-arms. Captains wear yellow or black, and the Marshal, blue. A seal of office is only granted to office-holders, which most gentlemen-at-arms are not. The Marshal wears a silver seal, while captains wear bronze or iron.

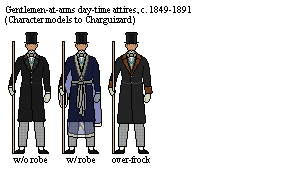

Modern

Following Emperor Ng'jarh's preference for Western-style clothing, his gentlement-at-arms started experimenting with that style beginning in the 1830s.

Notably, this followed certain military units that have already made that change earlier in the century. Ng'jarh's court was one of laxness and the power of prime ministers, some of whom were eager to show understanding and openness to foreign ideas as a device to garner respect or support. The emperor himself sometimes dressed in Casaterran style to entertain foreign guests in the Casaterran Annexe. However, the switch was not complete until the 1840s, since there was never any directive on what royal retainers might wear. One's prestige and royal patronage could be expressed through sartorial refinement since the beginnings of the institution, carried forth into the modern era. Many gentlemen would have converted to show support for various senior figures who were so dressed.

There was a hybrid dress code that dominated the court from around 1830 to the 1850s, where one wore Western clothes under the p′ru over-robe, as a nod to cultural continuity and domestic fashion, still active in circles that have not switched to Western clothing yet. Many Conservative ministers insisted upon wearing the p′ru at court, but it was never mandatory at any point; Liberals, on the other hand, wore it for major occasions and not others.

In general, the introduction of Western clothing was attended by Western social etiquette and lifestyles as well. In the 1830s, standard formal day-wear was the tailcoat, and indeed tailcoats were seen at court as reported by domestic and foreign sources; Emperor Ng'jarh was famously partial to mustard-coloured coats. By 1850, the tailcoat was confined to evenings, and the frock coat took its place during day. Gentlemen-at-arms mostly followed this trend, though tailcoats were still used while attending upon the sovereign as an expression of deference.

Recent reforms

The series of assassination attempts in 1940 – 41 on Emperor L′abh-tsung by Dayashinese infiltrators in the Themiclesian Marines caused a panic amongst the Privy Council abour security around the palaces. The gentlemen-at-arms on duty around the palace were unable to prevent the ingress of an infiltrator, who made it as far as the throne itself, where the emperor dinnered with his court. It was discovered that half of the gentlemen on duty perished resisting by melée weapons highly-trained operatives armed with rifles and pistols, while the other half sought refuge in a storehouse.

Themiclesian views about social classes prevented ordinary soldiers from coming into contact with the monarch or even setting foot in his vicinity. Such was punished as lèse-majesté. At the same time, Parliament was against legitimating military presence around itself, for fear of any form of military influence on its deliberations. Since it sat inside the palace hall, soldiers were legally barred from nearing Parliament as well. During previous emergencies, either the emperor left the palace hall to seek refuge in other palaces, or Parliament voted for to permit soldiers in the palace hall. These rules were not broken during the reign of Emperor Goi (1886 – 1919), believed to be a strong Liberal about traditions like these, and starting in Emperor Hên′s reign in 1921, Conservatives surrounded the throne, eliminating any suggestion that the traditional arrangement might be changed.

Foreign influence

Camia

Until 1881, the Camian president and parliament were both protected by forces known as gentlemen-at-arms. Camian gentlemen-at-arms were structurally different from their Themiclesian counterparts but had a largely similar function initially. Into the mid-1800s, they became more detached from civil service and were more akin to protégés to politicians, though they were always recruited from families of reputation like in Themiclesia.

However, President Acker III had few allies in politics and grew paranoid of their cadets. Acker formed new units from the best-trained men of the army and marines to stand guard at the president's mansion, that his security would not be entrusted to either the War or Navy Secretary. The units could further check each other. When the Camian Air Service was founded, they were likewise added to the guard of the president. Since then, gentlemen-at-arms were retained only as ushers and then not always filled. While some have called for their revival in the 1950s, the practice was criticized as anachronistic and against the principles of equality.

Privileges

Nomen audiundum

The privilege of nomen audiundum (智名, trjêh-mjêng) literally means having one's name heard, i.e. introduced by name to the emperor. The Ran-lang Collection shows that individuals above the rank of 600 bushels and members of the royal household with nomen audiundum may not be imprisoned except for flagrant offences or with the assent of the monarch; when they are arrested, they were placed under house arrest instead. Traditionally, gentlemen-at-arms serve terms of six years before embarking on their bureaucratic careers, and after the fifth, a lord in waiting introduced them to the emperor with the recommendation that

the noble youth has diligently attended Your Majesty's levée and coucher and moreover stood guard in the galleries through rain and snow; he has excelled amongst peers for his knowledge of laws and rules of accounting. Before he leaves Your Majesty to enters Civil Service, the secretaries of state pray Your Majesty may be pleased to look upon his face and remember his name, so that five years of difficult and unpaid services may be compensated by Your Majesty's acknowledgement.

Notably, it was ultimately up to the Ministry of Administration to decide who was introduced to the emperor, and the candidate gentlemen-at-arms would have been hard-pressed to come up with interesting conversations to attract the attention of the ministry.

Notes

- ↑ First Class was not available by tradition.