Papotement

Template:KylarisRecognitionArticle

| Papotement | |

|---|---|

| Gnun Tongo Karukais Kreòl | |

| Pronunciation | [ɲun ˈto.ŋo] [kʁeəl kaʁukais] |

| Native to | Carucere |

Native speakers | ~500,000 |

Gaullican-based creole

| |

| Solarian using the Papotement alphabet. | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Carucere |

| Regulated by | National Academy of Papotement |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | par |

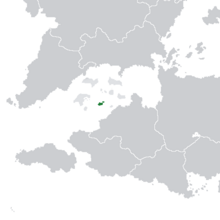

Location map of Carucere, where Papotement is spoken | |

Papotement (IPA: [pa.pɔ.te.mɑ̃]), locally known as Gnun Tongo (IPA: [ɲun ˈto.ŋo]), also known as Carucerean Creole (Papotement: Karukais Kreòl, IPA: [kaʁukais kʁeəl]), is a Gaullican-based creole language spoken by over half a million people in the Asterias. It is the most widely spoken language in Carucere, serving as the unofficial national language of the country.

Papotement has its origins from the Moutagnar creole spoken by enslaved Bahians on the Karukera colony in the 16th century, but the modern form of the language originates from the interactions between free Bahians and Gowsa workers, who mainly spoke Ziba, in the mid to late 19th century. The vocabulary of Papotement mostly originates from Gaullican, but its grammar draws influence from the Moutagnar creole and the Ziba language spoken by gowsa workers. Gaullican has played a major role in the creole since the mid-19th century, introducing the majority of the vocabulary as well as parts of the language's grammar, and methods of pronunciation. It is not mutually intelligible with standard Estmerish or Gaullican, and has its own distinctive pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar.

While Gaullican still remains the language of prestige, Papotement is the lingua gaullica of the Republic of Carucere. Carucereans tend to speak Papotement at home and in media; Gaullican is limited to administration and educational purposes. Though Carucereans are of numerous ethnic origins, including Southeast Coian, Bahian, and Euclean; Papotement has gradually replaced the ancestral languages of most the population to become the primary home language of the country.

Etymology

The word papute originates from Gaullican papoter ("to chat, chatter"). The word papotement is formed by adding the noun-forming suffix -ment. The word is ultimately derived from a colloquial term by Gaullican colonial administrators and settlers to refer to the new language spoken between Bahian and Gowsa workers in the late 19th century. The term was originally used to differentiate Papotement from the preexisting Moutagnar language spoken by Bahians, then known as Carucerean Creole by the Gaullicans. As the Moutagnar creole was subsumed into Papotement, some now use that term to refer to the latter.

The language's most common native name, Gnun Tongo (lit. "New Tongue"), also references its status and origin as a newer language. Other native names for Papotement include Karuku Tongo and Paputemanti.

History

Estmere was the first Euclean power to settle the island in the early 16th century after the destruction of the Karukera Confederacy. The decimation of the native population resulted in only a small portion of Papute vocabulary deriving from the Nati language. The population of the colony largely consisted of Euclean settlers and soldiers with some slaves. The language that developed was based on Estmerish, but differed greatly from the language spoken by the slave owners. This pidgin language eventually became the native language of the children of the slaves, where it developed into a creole.

Under Gaullican rule from 1724 to 1770, they rebuilt the plantation economy by importing additional slaves from across Southern Bahia to replace the slaves that escaped. There was only minor Gaulliacn influence on the creole as the size of the native Gaullican settler population on the island was small, the enslaved population was segregated from the colonissts, and the slaves lacked any kind of formal education. The new slaves learned the Estmerish-based creole from recaptured Maroons or those who never escaped, and adopted it as their main language.

After the Asterian War of Secession, Estmere once again took control of the island. The abolition of slavery in the 1790s led many Bahians to leave the plantations and form their own communities, where the creole language continued to evolve. Meanwhile, splits in the Amendist Church in Estmere in the early 19th century, led to several evangelical and fundamentalist churches seeking to convert the free Bahian population to Amendism. As part of their mission, they also taught Estmerish to them to create an educated class of Estmerish speakers. Despite their attempts to suppress the Moutagnar creole, it continued to be spoken by the population.

Gaullica regained control of the island after the War of the Triple Alliance in 1854. Gaullica once gain sought to establish a plantation economy, but they could no longer depend on slavery. Instead indentured workers from modern day Dezevau known as gowsa were brought to replace the freed slaves and became the plurality population on the island by the 1870s. Unlike the Bahian slaves before them, the gowsas universally used Ziba to communicate with each other. Carucerean Ziba would undergo partial creolization throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

As a growing number gowsas were freed from their indentureship contracts, they began settling down and establishing communities across Carucere, where they began interacting with the pre-existing Bahian communities. Modern Papotement arose when the gowsas, who mostly spoke the Ziba language, and the Bahians who spoke their creole, created a pigin language to communicate with each other. Colonial administrators continued to discourage the use of any language other than Gaullican, but the Bahian creole, Ziba, Kachai, and Papotement continued to be spoken at home. This pidgin is considered to be earliest modern form of Papotement. Individual reports of communication between the Gowsas and Bahians date to as early as the 1860s and 1870s, but it cannot be concluded whether or not these were describing a pidgin or a creole, as the reports only contained small samples. Linguistics believe that during this time, the development of the pidgin into modern Papotement was underway; a full creole is generally agreed to have formed by 1900.

The Great War from 1927 to 1935 was a pivotal moment for the development of Papotement. The war brought the collapse of Gaullican rule on the island and the end of the Holistique movement as the education system collapsed. The poor circumstances forced the Bahians and Gosas to cooperate together, where they used Papotement to communicate with each other. Common practices such as leaving young Bahian and Gosa children together in early versions of day-care centers during working hours accelerated the development of the language. Roch Mathieu, who lived in Carucere during the Great War period, wrote:

The next generation of children [in Carucere] will have a mixed language; the Gowsas and Bahians speak different languages but work together during these hard times. The children pick up a little of each language, and know little of the one originally spoken by their parents.

By the late 1930s, nearly all Bahian and Gosa children born in Carucere learned Papotement during their childhood, which became the common language in Carucere of both ethnic groups alike. The original Bahian creole was gradually subsumed by Papotement and many younger Dezevauni and Kachai started favoring the language instead of Ziba. Although an education system was restored after the war, it was largely secular and the Holistique movement was never reimplemented.

Papotement played a major role in the Arucian Naissance in Carucere throughout the 1930s and 1940s. In order to communicate between Bahian and Dezevauni members, the multi-ethnic popular movements of the time used the language. Various political movements conducted its business entirely within the language. Papotement quickly became a symbol of Carucerean opposition, especially after the regional government began targeting the use of the language due to its association with the Carucerean opposition. As the governmental authorities were largely unfamiliar with the language, Papotement words and phrases were used as secret codes by them to conduct their activities.

After the independence of Carucere in 1953, efforts were made to standardize the language. The National Academy of Papotement, created to regulate the language, was founded in 1974 by President Jean Preval as part of his progressive policies. The Academy published the first dictionary starting in 1974, establishing definitions and pronunciations for many common words and phrases. However orthography remained unregulated, and spelling remained disparate. The Carucerean government began supporting an orthographic reform in 2003, with a system that generally follows Gaullican but eliminates silent letters and reduces the number of different ways in which the same sound can be written. It was codified in 2005 with the publication of the fourth edition of the Diksione Paputemanti.

Origin

Papotement is unique compared to other creole languages due to diverse influence by many different superstrate and substrate languages. The Gaullican language is generally considered to be the superstrate, despite it not being the primary language of the Bahians or the Gowsas, due to its high prominence and widespread use in the Colony of Saint-Brendan. The Moutagnar creole and Ziba, along with Estmerish to a lesser extent, are the substrate languages of Papotement and are adstrates to each other as they share the same lower status compared to Gaullican. The complex interactions of these languages led to the formation of Papotement in the late 19th century.

There is significant debate on the relationship between Papotement and the Moutagnar creole. The current consensus is that Papotement emerged as an independent creole language heavily influenced by the other languages, but still separate from the original Bahian creole. However some argue that Papotement directly evolved from the Moutagnar creole after the introduction of the Ziba and Gaullican languages. Nevertheless it is generally agreed that based upon the grammar of the language, Papotement formed as an independent creole.

Moutagnar creole

The direct predecessor of Papotement is the Moutagnar creole or the Old Bahian creole (OBC) that developed during the 16th and 17th centuries. During Estermish rule, colonizers produced tobacco, cotton, and sugar cane on the islands. Throughout this period, the population was made of roughly equal numbers of white workers, settlers, free people of colour, and slaves. The slaves spoken an Estermish based creole. The majority of the Bahian slaves brought to the colony spoke a Southern Bahian language, particularly the Rwizi and Sisulu languages. It began as a pidgin spoken primarily by enslaved Bahians from various tribes in Suriname, who often did not have an language in common. As a result, a pidgin was formed from which a distinct creole emerged by the late 16th century. Known as the Bahian Creole, the majority of its vocabulary was derived from Estmerish, but its grammatical structure contained many features similar to South Bahian languages. These included some agglutinative features, but it was already much more analytical than its origin languages.

After Gaullica seized the colony in 1715, they sought to rapidly expand sugar production. The sugar crops needed a much larger labor force, which led to an increase in slave importation from Bahia. During this period an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 Bahian individuals were enslaved and brought to Saint-Brendan, nearly doubling the slave population. Although the Gaullican colonial authorities interacted very little with the slaves, the Estmerish creole was significantly influenced by the introduction of the Gaullican language which contributed many loan words. A similar debate exists on whether Papotement should be classified as an Gaullican-based creole or an Estmerish-based one. These arguments gemerally mirror the points of the aformentioned debate; similarly the general consenus that it is a Gaullican-based creole.

Gaullican

The Gaullican language arrived in Carucere after the seizure of the islands in 1721, where it would be used as the main language of administration during the two periods of Gaullican colonial rule from 1721 to 1770 and 1854 to 1935, during the Arucian Federation from 1935 to 1945, and under the United Provinces from 1945 to 1953. During this time, the language has a significant impact on the development of the creole, especially in vocabulary; over 80% of the lexicon is of Gaullican origin. Gaullican has directly and indirectly influenced Papotement vocabulary.

Estmerish

During Estmerish rule of Carucere from 1770 to 1855, evangelical and fundamentalist churches arrived to Carucere following major denominational splits in 1811 and 1844. Alongside converting the free Bahians to Amendism, they sought to teach them Estmerish to create an educated class to further increase conversions. The greatest influence of Estmerish in Papotement is through loanwords, especially for words of a religious nature such as "Lord". While most Papotement words of Estmerish origin were borrowed from the Bahian creole, which in turn derived some of their lexicon from Estmerish, some words were directly loaned from Estmerish.

Ziba

Ziba was the main language spoken by gowsa workers imported to Carcuere in the mid to late 19th century. The gowsas were subject to gaullicanization efforts as part of the Holistique movement, which pressured them to adopt the Gaullican language. Thus by the time Papotement began to form, Ziba in Carucere was undergoing partial creolization. The majority of Ziba's contribution to the creole is in grammar, especially grammatical markers and sentence structure. In additional Papotement has many Ziba loanwords for concepts and items that originate from Southeast Coius.

Other Gowsa langauges

Although gowsas overwhelmingly spoke Ziba, the indentured workers were imported from a vast geographical area and usually spoke other languages. These languages include Kachai, Pelangi, Kabuese, and other South Bahian languages. However these languages gradually fell out of use as they primarily used Ziba to communicate and only has a minor influence in Papotement, although many loan words originates from these languages.

Varieties

Standard Papotement is defined by the Diksione Paputemanti and the Papotement Guide both published by the National Academy of Papotement. Standard Papotement was declared the national language in 1996 during the reforms throughout the 1990s and early 2000s that standardized its grammar, spelling, and pronunciation. However the National Academy has stated that the standardized language does not replace the various dialects of Papotement and was only standardized for use in formal situations such as education and media. However in the past few decades standardisation, mass media, and education has had a noticeable impact on the diversity and depth of the language's dialects which has caused some controversy and discussion.

Dialects

Unlike many other languages, Papotement's dialects correspond to Carucere's ethnic groups rather than geographic location, although due to the geographic distribution of ethnic groups there is some correlation. Although the Edward Strait forms a natural barrier between the two main islands, Carucere's size and population density means that dialects cannot be meaningfully distinguished from each other and instead are blurred together. Papotement forms a multi-polar dialect continuum between Carucerean Ziba, Moutagnar creole, Estmerish, and Gaullican, corresponding to the country's ethnic and religious groups. Nevertheless four broad categories can be ascertained determined by the amount of influence of their parent languages has on the dialect. Influences largely manifest as distinct accents and the use of loanwords of slang from parent languages, which increase the greater the influence is. At the most extreme examples, the dialect is mutually intelligible with its parent language, even if standard Papotement is not. In recent decades, linguists have argued that Moutagnar creole was not completely subsumed by Papotement, but continues to exist as a modified form that closely resembles the Papotement Bahian dialect or is in fact the main Bahian dialect.

Phonology

Consonants

Papotement has a total of 20 consonants largely drawn from its source languages the Moutagnar creole and Ziba, but it has developed a distinct inventory unique to the language. Notable features include distinguishing between voiced and unvoiced consonants, the usage of affricates, and a lack of breathy voice and sibilants as distinct phonemes. The phonology described here is for standardized Papotement; the language's distinct dialects include greater phonological influences from its substrate languages.

| Bilabial | Labio-dental | Alveolar | Postalveolar / Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | Voiced | b | d | g | ||||

| Voiceless | p | t | k | |||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||||

| Fricative | Voiced | v | s | ʁ | ||||

| Voiceless | f | z | ʃ | h | ||||

| Affricates | d͡ʒ | |||||||

| Approximant | ʋ | j | ||||||

| Lateral Approximant | l | |||||||

Vowels

Papotement has seven vowels, not including three nasal vowels; /ɑ̃/,/ɛ̃/, /õ/.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Close-mid | e | o | |

| Mid | ə | ||

| Open | a | ɒ |

Papotement has fourteen diphthongs, two vowels in a single syllable that form one sound. Papotement diphthongs are based on Gaullican and Ziba diphthongs.

| Diphthongs | |

|---|---|

| IPA | Papotement orthography |

| ao | ao |

| oa | oa |

| ia | ia |

| ua | oua |

| ai | ai |

| oi | oi |

| io | io |

| uo | ouo |

| au | auo |

| ou | oou |

| iu | iou |

| oiu | ui |

| iːə | iò |

| uːə | uò |

Phonotactics

Papotement allows a syllable structure of (C)3V(C)3. The largest consonant cluster allowed in Papotement are three consonants like in Estmerish.

Grammar

Papotement is a highly analytical language. Papotement's grammar is based upon Moutagnar creole, which in turn is derived from Estmerish, with significant influence from Ziba. Words are rarely inflected in Papotement and are instead noted by grammatical markers or the context. Grammatical markers are special words that are used to modify a word's or phrase's meaning or state and is widely used in the language. Although the markers originates from Bahian Creole, many grammatical markers in Papotement are derived from Ziba grammatical affixes and suffixes.

Nouns and adjectives

In Papotement, grammatical markers are placed next to nouns to determine number and possession. For example, possession is indicated by the marker so placed before the noun; Sarah so liv ("Sarah's book"). Although the high degree of compounding and affixes found in Ziba is largely absent in Papotement, noun phrases are commonly used to express complex concepts. In addition certain markers can be used to create adjectives from nouns. For example, the adjective-forming suffix -bo ("made of", "full of") in Ziba is used in Papotement as an general marker in front of the noun. Compare Ziba zuanibibo ("made of sandstone") with Papotement bo gre ("[made] of sandstone") and bo deside (lit. "[full] of decision", "decisive"). Papotement's definite article la is placed after the noun. The Papotement indefinite article en is placed before the noun. Reduplication is a common morphological phenomenon in Papotement, where a part of a word is repeated to modify the meaning of a word. It is commonly used to indicate frequency or intensity of the action indicated by the original verb stem. For example, frape means "to hit", frape frape means "to hit repeatedly". In addition it can be used to emphasize the meaning of the repeated word in the context that it is used. For example So kouri kouri vit ("He runs fast") means that he has been consistently running fast, while So kouri vit vit ("He runs fast") emphasizes the speed of the running. Words can be repeated more than twice to further emphasize the meaning.

Pronouns

Papotement's singular and plural personal pronouns lacks grammatical gender entirely. For example so , which also functions as possessive pronoun, is equivalent to "his/her". Papotement also has the pronoun, li which can cover all plural pronouns and the third-person singular pronoun, regardless of case or gender. Thus li can be translated as "he, she, it, him, his, her, and hers" depending on the context. Reflexive personal pronouns are created by agglutinating the suffix mem (same) to a pronoun; to ("you") tomem ("yourself").

Number and plurals

Nouns do not change according to grammatical number; whether a noun is singular or plural is usually determined only by context. For instance, bann vit is "many books"; while vit individually implies a singular book, including the term bann ("many") implies there are multiple books. The particle grup (from groupe) is sometimes placed to create a plural word for emphasis or if a plural word cannot be determined by context. The Papotement indefinite article en also is the number one, so "one book" and "a book" are both translated as en vit in creole.

Demonstratives

The word sa ("this" "that") is used as a demonstrative after the noun that it modifies. It may also be used as a pronoun, replacing a noun.

Verbs

Verbs in Papotement are not inflected for voice, mood, number, or person. Tense is determined by an appropriate grammatical marker placed next to a noun or pronoun. No markers are needed to indicate present tense, but Papotement's three additional tenses are; pe marking progressive aspect, pou marking the future tense, and ti marking the past tense. Tense markers can be combined to create combination markers to create more complex phrases. For example, combining the markers ti with pe creates the marker ti pe, which signifies an ongoing event but in the past. Two major verbs are ena ("there is", "there are", "have") and pena the negative of the former. Ex: Ena en vit ("There is a book"), Pena vit (There is no book). Adverbs and participles are formed using the same system. Examples are the negative marker pa, which changes the verb's meaning to the negative and the marker ju equivalent to Estmerish "-ly"; both are placed before the word it modifies.

Copula

There is only one copula in Papotement, the word ete which is only used when the subject of a sentence is a person. Otherwise copulas such as the verb "to be" are entirely absent in Papotement.

Syntax

Papotement largely uses subject–verb–object word order. The language allows complex noun phrases, which can include long relative clauses, within a SVO sentence. This is similar to Ziba grammar with grammatical markers taking the place of conjunctions and compounding. Paoptement more commonly uses double object constructions ("The woman gave her son the money.") than indirect object constructions ("The woman gave the money to her son."), although the latter is used when the indirect object is the focused element. Relative clauses are created with the marker sa ("that") placed in front of the clause.

Lexicon

Over 80% of Papotement's vocabulary is derived from Gaullican from the late 19th century, albeit with significant changes in pronunciation and morphology. Due to its complex history, many Papotement words that originate from different languages share similar definitions. For example, the Papotement words rele ("to call by name") and heil ("to greet informally") both have similar meanings but are derived from different languages; the former comes from Gaullican héler ("to call over loudly") and the latter from Estmerish hail ("to greet"). Some Gaullican words originate from the first period of Gaullican colonial rule, although this is limited to very few words. The remainder of Papotement vocabulary originates from its two main substrate languages, the Moutagnar creole and Ziba.

Moutagnar creole's vocabulary originates from 16th century Estermish and thus often maintains archaic definitions and pronunciations. For example, the "silent" consonants found in the consonant clusters of modern Estmerish in words as knot, gnat, sword continued to be pronounced Moutagnar creole and left an influence in modern Papotement. Another notable contribution is bledi from Estmerish "bloody", although it is only used as an intensifier and completely lacks any profane connotations. The majority of Moutagnar vocabulary in Papotement are for everyday objects and local geography.

Ziba is the second largest source of words in Papotement. The majority of these loanwords were concepts, objects, and ideas introduced by the gowsas and their descendants from their place of origin. These include contributions such as Papotement veg from Ziba venge ("breadfruit"), dobo mede from daubo mhedhui ( "congee"), zibu ("several"), and debu ("many; more than twenty") from dhebu ("twenty" "many"). Many inflected Ziba words were directly borrowed with root and suffix to form whole words such as . In addition many grammatical markers originate from Ziba grammatical suffixes.

There are minor influences from Southern Bahian languages, such as makutu from eOnikhuma makhwatta "(running sore)" and other Southeast Coian languages, such as kawo niòu ("sticky rice") from Kachai ເຂົ້າໜຽວ (khao niāu). Other minor sources include Champanian, Nati, and various regional languages.

Orthography

Papotement is written in the Solarian script with a phonemic orthography with highly regular spelling, except for proper nouns and foreign loanwords. According to the official standardized orthography, the Papotement alphabet is composed of 32 letters.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sociolinguistics

Although both Gaullican and Papotement are official languages in Carucere, Gaullican has long enjoyed greater social status and is main language in government, business, and education. While Papotement is considered to be the low language in the diglossic relationship between the two languages in society, the vast majority of Carucereans speak the language on a daily basis, especially in informal situations. The government has promoted the use of Papotement in media; The Strait, Carucere's paper of record, publishes its primary edition in Gaullican and Papotement. However in other formal situations, Gaullican is highly encouraged; these situations is one of the few instances when the use of Papotement is stigmatized.

Literature and culture

Carucere's national anthem, "Karuke Tere Nou", is in Papotement. The newspaper Diario and The Strait Times publishes an edition in the language.

Zegodu letter

The oldest surviving written text in Papotement is a short letter dated from 1886, discovered in a private book collection in Pointe Henri in 2007. The letter was sent by a young Gosa woman named Zegodu to her friend Elise, inviting her to her birthday celebration. Although their lineage can be traced from their modern descendants, little else is known about the two women or their relationship to each other. It is believed that it was written by the first generation of native Papotement speakers, and thus contains archaic vocabulary and grammar. The letter is currently stored at the National Library in Jameston and a reproduction is on display at the National Museum of History.

| Papotement | English | |

|---|---|---|

|

Mi reme et kamarad, Mo donn to tied et envitasyon pur selebrasion de mo aniveser 14 Septanm. Mi avid ju atadr to vizit, pur i rann pou mi lizour plu plu agreyab. Mi heila pou debu kamarad tu fete pou de midi jeme tu kontan dajab. Bonzour to mama pur mi, et tou to fanmi. Mi papa et mama avoy bann-laz zot bonzour. Ziska lè sa a pouvwa Ou Dieuc donn to sante. Au revoir, orevwa cheri. |

My dearest friend, I give you the warmest invitation for the celebration of my birthday on 14 September. I eagerly await your visit, for it would make my day much more enjoyable. I will call many friends to celebrate from noon until we are happiest. Greet your mother for me, and all your family. My father and my mother send them their greetings. Until then may your God give you health. Au revoir, goodbye sweetheart. |