Geography of Menghe

| |

| Continent | Hemithea |

|---|---|

| Region | Septentrion |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3,719,849 km2 (1,436,242 sq mi) |

| • Land | 93.9% |

| • Water | 6.1% |

| Highest point | Mount Tae 4,537.5 m |

| Lowest point | (sea level) |

| Longest river | White River 3,029 km |

| Largest lake | Lake Hongsu 1,176 km2 |

| Climate | Generally temperate and continental climate, semi-arid in northwest, some alpine tundra; monsoon-influenced in central band, stable precipitation on east coast |

| Terrain | Mountains in center-west and along east coast, plains from northeast to southwest, steppe in northwest |

| Natural Resources | coal, iron ore, bauxite, uranium, oil, timber, arable land |

| Natural Hazards | earthquakes, floods, typhoons, tsunamis, landslides |

| Environmental Issues | air pollution, water pollution, desertification, deforestation, soil erosion |

Menghe lies on the southeastern section of the continent of Hemithea in Septentrion. Its northern border with Polvokia is defined primarily by the lower course of the White (Baek) River, and its southern border with Innominada, now Argentstan, is defined by the River Argun. Its other land borders, defined by treaty and generally not following waterways, are shared with Dzhungestan, Maverica, and the People's Republic of Innominada.

Menghe's geography is broadly defined by two major mountain ranges: the high Chŏnsan Range, which curves from the western border to terminate in the north, and the more moderate Donghae Range, which runs along the east coast and forms a fragmented highland pattern in the southeast. Between these mountain ranges is a large and relatively level plain, where abundant rainfall during the summer monsoon season feeds a rich network of rivers and lakes. Conventionally, this level area is divided between the Upper Meng Basin between the Chŏnsan and Donghae ranges, the Chŏllo Plain in Menghe's center-south, and the Kala-duzun plain in the southwest. The area northwest of the Chŏnsans, mainly comprised of arid steppe and scrubland, is known as Sansŏ, and the northern area of the country - usually demarcated by the boundary between the Meng and White River watersheds - is known as Bugrim.

Area

Several figures exist for Menghe's area, depending on how it is measured. The "official" figure, 3,492,396 square kilometers, includes all rivers and lakes, but does not include Menghe's coastal waters. Land area alone, excluding rivers and lakes, is 3,473,394 square kilometers. Menghe's internal waters and territorial waters add an additional 227,468 square kilometers, bringing the total to 3,719,849 km2. These figures, published in 2018 by the Ministry of Information and Statistics, include recent expansions to land area due to the use of coastal landfill to construct airports and container terminals.

The Ministry of Information and Statistics lists both of these figures as "administered area" (관제 면적 / 管制面積, gwanje myŏnjok). Altagracia, if included, would add another 597 km2 of land area and 2,762 km2 of sea area, but it is currently ruled by an independent government with commonwealth ties to Sylva. Menghe claims the entirety of Altagracia as the Goŭn Peninsula (고은 반도 / 高恩半島, Goŭn Bando), citing an 1853 treaty which only ceded it for a 99-year lease, while Sylva claims that the lease was extended indefinitely in 1951, an agreement which Menghe does not recognize as legitimate because it was not ratified by a sovereign Menghean government.

The territorial waters around Altagracia are also contested. Menghe claims the entire Daman Sea, from Channakale to Juman point, as internal waters, a claim which fully encloses Altagracia in Menghean internal seas. Menghe also claims all waters up to Altagracia's coast, but agreed to respect the 22.2 kilometers around the peninsula as a "safe exclusion zone" in 1992. Altagracia also refuses to recognize Menghe's claim to the entire Daman sea, treating it as international waters, while Menghe insists that it has the right to decline passage to any ship traveling between Altagracia and the open ocean. The 1992 provisional agreement set aside a 3-kilometer-wide transit route through Menghean waters, but Menghe still claims the right to inspect ships on this route, and since 2014 it has denied passage to Sylvan military vessels.

Tectonics

Menghe's terrain was shaped by the divergence of the South Hemithean and East Meridian tectonic plates. The South Hemithean Plate, which includes nearly all of Menghe's territory, is currently drifting northwest away from a divergent boundary at the bottom of the South Menghe Sea. The Chŏnsan Mountains, which run from western Maverica to northern Menghe, follow a convergent boundary tracing the opposite edge. In north-central Menghe, they terminate with a transform boundary that runs northwest to resume convergence again in Polvokia's Buksan mountains.

The forceful westward movement of the North Helian Plate, which formed the islands of Dayashina and raised Polvokia's Northeast Plateau, applied additional convergent pressure. Though originally part of the South Hemithean Plate, and often grouped together with it on maps, the East Menghe Sea Plate and the Polvokian Lower Plate drift at slightly different angles due to the North Helian Plate's pressure, forming minor plates with their own tectonic boundaries. In Menghe, the convergent boundary with the East Menghe Sea Plate traces the Donghae Mountain Range along the east coast.

Physical regions

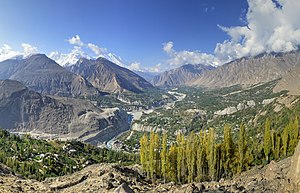

Chŏnsan mountains

The Chŏnsan mountains (천산 / 天山) are Menghe's most defining geographic feature, dividing the country between southeastern and northwestern plains. They are the highest area in Menghe, and among the highest areas in Hemithea, surpassed only by the Buksan mountains in Polvokia. The highest mountain in the range is Mount Tae, or Taesan, with a peak 4,537.5 meters above sea level. With their sharp ascent and high altitude, the Chŏnsans end the northward drift of the Intertropical Convergence Zone in summer, dividing the country between abundant seasonal rain to the south and semi-arid steppe to the north.

The upper valleys of the range are lined with glaciers, fed by annual snow from the monsoon pattern. Meltwater from the glaciers feeds the heads of several of Menghe's rivers, including the Ro river to the south, the White river to the north, and parts of the Sŭllŭnge river into Dzhungestan. Several of these rivers, particularly the Ŭm and White, have carved out vast valleys. Because of its high peaks, unique scenery, and isolation from urban life, the Chŏnsan region is becoming an increasingly popular destination for Menghean and foreign tourists and hikers.

During the Menghean War of Liberation, the Chŏnsan range was the site of the Chŏnsan Expedition, also known as the Arduous March, in which General Yang Tae-Sŏng led the Eighth Army from Suksŏng to Jinjŏng. The Eighth Army's recorded route today serves as an attraction for Menghean nationalists, some of whom have retraced the route on foot.

Donghae mountains

Running along the coast of the East Menghe Sea, the Donghae Mountains (동해산 / 東海山) are Menghe's other major mountain range. They are not as tall as the Chŏnsans; while a few major peaks, like Hasŏlsan (하설산 / 夏雪山), retain snowy caps year-round, most of the region is fairly temperate, with altitudes rarely surpassing 1,500 meters. Steady year-round precipitation feeds a large number of small rivers and brooks, but most run directly out to sea, with none of the large, interconnected river networks seen in western and central Menghe.

Much of the rock in the Chŏnsan range is soft limestone, which is easily eroded by heavy rain and mountain waterways. It includes a number of spectacular karst formations, particularly in the area around South Donghae and Central Donghae provinces, where erosion has shaped landscapes of narrow mountains and winding caves. North Donghae is lined with more conventional fold-like ridges, and the southern end of the range breaks into a maze of valleys and high-level basins, shaped by conflicting pressures from the South Hemithean and East Menghe Sea plates.

Central basin

The central basin, also known as the Meng River basin, is the name applied to the low-lying area between the Donghae and Chŏnsan mountains. Here, the terrain is relatively flat, gradually rising to the foothills of the mountains on either side. The basin is about 500 kilometers across and 1,000 kilometers deep, and nearly all of its precipitation drains into the Meng River, which runs along its center, fed by a sprawling network of tributaries and minor rivers.

The central basin's southern edge is conventionally drawn through the city of Hwasŏng, where the Meng River reaches the Chŏllo plain. Its northern boundary is less clear. Some regard it to continue all the way to the Polvokian border, over a stretch of elevated land between the ends of the Chŏnsan and Donghae ranges, while others limit it to the Meng River's watershed. In the latter measurement, the remaining northern area, roughly corresponding to the provinces of Songgang and Girim, is known as the Mengbuk region ("north of the Meng").

Chŏllo

The Chŏllo Plain refers to the low-lying area between the Chŏnsan Mountains and the South Menghe Sea. Its western boundary is conventionally set at the Wŏl river, and its eastern boundary has been variously defined as the lower Meng watershed, the lower Meng river, or the foothills of the Donghae highlands. At its center is the Ro river, which, like the Meng, branches outward to link a historical network of barge-trading cities. The Chŏllo basin is slightly hilly, pushed upward by tectonic movement to the south, and gradually ascends to the foothills of the Chŏnsan range, where it abruptly rises to some of the country's tallest peaks.

The name Chŏllo (천로 / 千鷺) dates back to at least the 3rd century BCE, and means "thousand herons," likely a reference to the large flocks of marsh birds that visitors saw in its marshes and swamps. Note that this is written as chŏn-ro, but under Standard Menghean pronunciation, combined to form an "l" sound. Chŏllo's herons also brought the Ro river (로강 / 鷺江, Rogang) its current name, though prior to conquest by the Meng dynasty, locals knew it as the Wŏl river (越江).

Like the central basin, the Chŏllo plain is heavily influenced by monsoon patterns, but it is also warmer and drier in the winter. In ancient times its population was largely nomadic, especially in the north, but under Menghean imperial rule it developed into an agricultural region with a vast irrigation system feeding flooded rice paddies.

Kala-duzun

Geographically, Kala-duzun is a continuation of the Chŏllo plain, which sweeps westward across southern Maverica to the Meridian Ocean. It shares a similar climate and similar topography. The boundary, usually drawn along the modern Wŏl river (월강 / 粵江), is largely cultural, as the Kala-duzun area is mainly inhabited by Daryz, Uzeri, and Argentan ethnic groups rather than Meng. This area also lacks navigable river or canal connections to the rest of Menghe, which historically limited its integration. Most of its area feeds the Seyhan River, which flows westward across the Maverican border, preventing shipment out to sea and along the coast.

Due to a combination of relatively level terrain and less attention to canal management, the Kala-duzun portion of the plain is characterized by poor drainage, with much of the monsoon rain gathering in seasonal marshes and lakes rather than flowing out to sea. Many of these marshes then evaporate in the dry winter months, or drain out more gradually. In the last several decades, efforts to reclaim more arable land on the Menghean side of the border have led to a loss of marshland, with the once-meandering Seyhan river routed into a relatively straight and stable course.

The Menghe-Maverican border, which runs through the Kala-duzun, is one of the most heavily militarized international borders in Septentrion, and the plains themselves would be the site of significant fighting if a war broke out.

Sansŏ

The Sansŏ region (산서 / 山西, "west of the mountains") lies northwest of the Chŏnsan range, and is part of the Central Hemithean Steppe. On Menghe's side, the land gradually slopes downward from the foothills of the mountains, in a rugged pattern of folded hills and small valleys. Though not a true desert, this area receives relatively little rain even during the summer months.

The eastern half of the Menghean Sansŏ is defined by the upper White River, which flows north from the Chŏnsan mountains into the Sanhu basin before turning east to the Menghe-Polvokian border. Farming along the river's floodplains historically supported a small sedentary population. Further west, the land slopes steadily westward, with the Sŭllŭnge river system flowing across the border to Dzhungestan. Historically, this area was the frontier of Menghean administration, and while some dynasties like the Yi extended their control across Central Hemithea, most exercised little authority beyond the White River watershed.

Rivers and canals

Meng river

Though not the longest river in Menghe - a title which belongs to the White - the Meng river (멩하 / 孟河, Meng Ha) is the most famous. Etymologically, its name can be translated as "eldest river" or "most eminent river," as it is much wider than the other rivers on its lower route and absorbs water from all tributaries in the middle of the country. The Meng river has a drainage area of approximately 978,000 square kilometers, including the entirety of the Meng plain, and much of that area receives heavy rainfall during the summer monsoon season. Glacial meltwater from the Chŏnsans and runoff from the West Donghae range feeds it during the drier months. It produces an average annual discharge of 20,638 cubic meters per second, but this can rise to 80,000 cubic meters per second during an El Niño flood season. Shortly before breaking up at its delta, the Meng reaches a width of 9 kilometers.

Historically, the Meng river formed an important cradle of Meng civilization. All three present-day Menghean-language names for Menghe - Dae Meng (大孟 / 대멩), Mengguk (멩국 / 孟國), and Menghwa (孟華 / 멩화) - refer to the Meng dynasty, which was named for the State of Meng, which in turn took its name from the river at its southern edge. Owing to its long length and many navigable tributaries, the Meng river system formed a vital transportation network in the days before the introduction of railroads, allowing barges to cheaply carry supplies between any major cities on the central plain.

The Meng river's many branches and winding course have led to some debate about its ultimate source. For much of history, only the 1,400-kilometer section south of Pyŏngchŏn was known as the Meng River; there, it divided into the Yi and Wu rivers. The first international figures for its total length used the Yi and Jang branches that flow through Bakgajang, for a total length of 2,191 kilometers; but in 1922, the official waterhead was moved to the foot of Mount Godongsan in North Donghae Province, and the entirety of the Yi river through Jinyi, which raised the overall length to 2,285 kilometers. This is generally accepted as the longest possible distance from the Meng river's mouth to any of its various sources.

From the early 20th century onward, the breadth of the Meng River posed challenges for transportation. South of Sapo, the river averages over 1.5 kilometers across, and while there are occasional reports of temporary pontoon bridges built during military campaigns, for centuries there were no permanent bridges on the Meng river proper. The two-level Junggyŏng Grand Bridge, built between 1925 and 1929, was the first modern crossing, and at 1,135 meters it was the longest bridge in Menghe at the time. In recent decades, a flurry of road and rail construction has overcome this barrier, and the longest Meng River crossing is over 8 kilometers in length.

Ro river

The Ro River (로강 / 鷺江, Rogang), or Heron River, formerly known as the Wŏl River (월강 / 越江, Wŏlgang), is the main river on the center of the Chŏllo plain. It begins north of Kaesan in the Chŏnsan mountains, and runs southward through Wichang, Busin, Insŏng, and Sunju. Like the Meng river, it is fed by a combination of glacial meltwater and monsoon rain, and its discharge rate varies over the course of the year. Though less extensive than the Meng, it does serve a broad area over its tributaries and branches, and it played a major role in shipping within the Chŏllo region, especially after linked to the Meng via the Two Rivers Canal.

The Ro River terminates in a broad, flat, and fairly marshy lowland area, where it branches into a wide river delta surrounded by large lakes. Over the centuries, residents added a network of canals for irrigation, shipment, and flood control, eventually linking the Ro River to the Ryang at Tongju. High levels of sediment discharge from the base of the river keep the soil fertile, allowing for rich harvests of deepwater rice, but they have also accumulated as sediment on the sea bottom; the large gulf south of Sunju is known as Hwangsa Bay (황사만 / 黃沙灣) for the yellow sandbars around which expert pilots had to navigate incoming ships.

White river

The White River (백강 / 白江, Baekgang) is also known as the Baek River. With a total length of 3,029 kilometers, it is the longest river to lie entirely within Menghe, but because much of its course runs through semi-arid terrain, its discharge rate at the mouth is only 11,540 cubic meters per second, including water from Polvokian tributaries that join near the mouth. The White River originates in the Chŏnsan mountains, and for some time runs in a valley parallel to their peaks, before turning northward through Sanhu province and then running east toward the East Menghe Sea. Along the final 1,121 kilometers of its length, the White River delineates Menghe's border with Polvokia.

Along its central course, roughly from the city of Ryŏjin to the Polvokian border, the White River carves canyons and gorges through the soft sandstone rock. Next to the city of Hapsŏng, it plunges sharply in the Great Northern Waterfall. Both the waterfall and the canyons around it are popular sights for tourists, drawing millions of visitors every year.

During several dynasties, the middle stretch of the White River defined Menghe's frontier with the Central Hemithean nomads. Its waterfalls and rapids made it an unreliable shipping route, and in most winters it froze over in large sections, allowing nomadic invaders to cross on horseback. Fortresses, watchposts, and walls on the southern bank were necessary to bolster its natural defenses. The northern province of Gangbuk (강북 / 江北), meaning "north of the river," was incorporated during the Myŏn dynasty after a war with the East Dzungar tribes, and its own northern border was a subject of dispute with Polvokia until 1937.

Canals

Because river barges were the most efficient method for transporting passengers and bulk goods before the introduction of the railroad, engineers in Imperial Menghe expended great effort to make tributary rivers navigable, building dams, weirs, and locks to help barges move upstream.

The highest culmination of this effort came in large-scale projects to link different river systems through manmade canals. These revolutionized early transport by allowing barges to more easily move around the country, and were particularly important in ferrying tribute and bulk trade goods between the Imperial capital, usually located on the Meng river, and cities elsewhere in the country.

Two Rivers Canal

The Two Rivers Canal lies in Hasŏ province, where it links the Min River, a tributary of the Ro, with the Punsu river, a tributary of the Meng. The excavated canal itself is only 44 kilometers long and crosses fairly level terrain, with no weirs, locks, or elevation changes. The main engineering challenge in its construction was the broader water management system needed to make the passage navigable for barges. Both the upper Ro and the upper Punsu were widened, straightened, and deepened, with work teams dredging out sediment into embankments on either side. A permanent connection between Lake Tae and the upper Min, with floodgates on its upper course, allowed the vast lake to be used as a storage reservoir, reducing flood risks in the summer and providing a steady supply of water in the dry season. When altered sections of river are included, the canal is 276 kilometers long.

The core components of the Two Rivers Canal were built at the height of the Meng Dynasty under Emperor Mu Je, who used the new connection to pull the newly acquired Chŏllo plain into Menghe's economic orbit. Over the centuries that followed, it would be regularly repaired, reinforced, and expanded, with special attention to the water management system feeding it. Today it remains a strategic route for barges and watercraft, and is particularly attractive for its lack of lock gates south of Lake Tae.

Grand Gangwŏn Canal

The Grand Gangwŏn Canal was built later, under the Sung dynasty, though attempts at digging it began under the Meng and Kang. It links the Jade River in Ryŏngsan with the Anchun river in Gangwŏn, and lies directly on the present Ryŏngsan-Gangwŏn border. Though the Jade river is shorter than the Ro, and was only navigable out to two cities, Yŏngjŏng and Ranju, it provided a direct shipping route from Hwasŏng to the East Menghe Sea. This helped integrate the Donghae region into Menghean water trade, avoiding the long and hazardous route along the Ryŏngsan coast.

The Grand Gangwŏn canal required only five and a half kilometers of digging, but it ran over much more challenging terrain. Though it began at the least challenging curve along the Jade river's bank, it required engineers to dig the initial spillway through solid rock, in some places twenty meters deep. The canal's remaining stretch, 41 kilometers long, mostly followed the course of a stream winding through the valleys, but had to be widened and reinforced to handle the large inflow of water from the Jade. Due to the 76-meter elevation difference between the two rivers at the connection points, the canal required a series of pound locks, among the first in the world at the time.

South Chŏllo Canal

The South Chŏllo Canal links the Ro and Ryang rivers near their mouths, running from Sunju through Tongju to Dongchŏn. Unlike the other canals, which were state projects to improve infrastructure, the South Chŏllo Canal began as a series of independent minor canals which had originally been dug to irrigate longwater rice fields and bring harvests to the nearby cities. The existing canals were linked and widened under the Sŭng dynasty, resulting in 72 kilometers of canal navigable by freight barges. To shorten the distance, the canal passed through several lakes, and used others as reservoirs to replenish water flows during the dry season.

Climate

Menghe sits between the 26° and 50° latitude lines, in a generally temperate band of Septentrion, but its climate varies considerably across its land area. In general, the climate runs on a spectrum from cold in the northeast to warm in the southwest, and from dry in the northwest to humid in the southeast. Ancient Menghean writers and philosophers attributed each of these tendencies to a primordial deity.

The real source of climate patterns in Menghe is the East Septentronian Monsoon System, a seasonal oscillation in weather patterns which is driven by the warming and cooling of inland Hemithea and Meridia. In the summer months, a low pressure system over the Central Hemithean Plateau draws warm, humid air from the South Menghe Sea over the country's southeastern mountains and plains, resulting in higher temperatures and heavy rainfall. In the winter, a high-pressure system in Central Hemithea reverses this effect, driving cold, dry air from the inland steppe over the south. This seasonal oscillation of wet summers and dry winters has major effects on climate and agriculture, particularly on the Chŏllo plain, where it is most pronounced. It also leaves Menghe vulnerable to multi-year oscillations in the intensity of the monsoon system; El Niño years result in severe drought, as the summer rain systems do not move far enough inland, and La Niña years result in heavy rainfall and inland flooding.

These seasonal shifts are less pronounced in the Donghae region, which benefits from close proximity to the East Menghe Sea. Here, southerly and southeasterly winds in the winter months still draw humid air from over the sea, bringing additional precipitation which compensates for milder rain in summer. In the south, around Ryŏngsan province, this precipitation falls as a second rainy season, allowing for two or even three rice harvests a year; further north, in North and Central Donghae, it falls as heavy snow.

The Sansŏ region is not only further inland than the coast, but also located beyond the high Chŏnsan mountains, which cause any remaining clouds to drop the rest of their moisture as they rise to pass overhead. As a result, its climate is markedly more arid, with under 300 millimeters of precipiation per year in most areas. The cold, semi-arid climate is not a true desert, but supports a scrubland landscape of shrubs and grasses, growing on yellowish soil blown across the steppe.

Natural disasters

Earthquakes

Menghe lies on several active tectonic faults, mainly in the east of the country but also running through the Chŏnsan range. The complex network of faults stems from the pressure created by the East Helian Plate's movement into the side of the South Hemithean Plate, fragmenting the latter into minor plates and microplates and generating less systematic fault lines.

In some areas, minor earthquakes measuring below 4 on the Richter scale are measured almost weekly, though they cause little damage. Larger earthquakes, of magnitude 7 or above, tend to occur every 20 years on average, though they are concentrated in the most severe fault areas. Along the mountainous Donghae region, earthquakes can also set off landslides, especially after heavy rain or snow. Transform faults off the southwest and along the middle of the South Menghe Sea also create a risk of Tsunamis, though most Menghean earthquakes occur inland and tsunami damage is less common.

Serious earthquake damage in the late 20th century led to steady improvements in building codes, particularly near known areas of tectonic activity. No major high-rise buildings collapsed in the Haeju Earthquake of 2016, which reached 8.7 on the Richter scale, though some had to be marked for repair or demolition afterward. Yet in poorer areas, codes are not always enforced as well, especially where corruption is prevalent. Deaths in school, apartment, and roadway collapses are a frequent source of protest against the regime, and particularly against local governments.

Volcanic activity

Despite its high tectonic activity, Menghe has only three volcanoes which have been active in the last 500 years, and all are currently dormant, with the most recent eruption in 1835. The subduction zone along the Chŏnsan mountains is a collision between two inland plates, rather than an undersea subduction of the kind driving Dayashina's volcanic activity, and in other areas like the Donghae range there is no clear subduction of one plate under another.

Flooding

Menghe's monsoon-influenced climate makes certain areas prone to serious flooding, especially during the rainy season. In some coastal areas, monthly rainfall exceeds 200 millimeters in April through August, and particularly big storms can deposit several centimeters in 24 hours. Heavy rainfall is intensified by flat terrain on the central basin and Chŏllo plain, and especially around the low-lying Ro river delta, which can also be inundated by storm surges that follow incoming typhoons. The Meng and Ro rivers themselves, which have large, monsoon-fed watersheds and follow relatively level terrain, were historically prone to flooding, which could be devastating for canal cities further downriver.

Flood control represented a major priority for many past Menghean governments, with large reinforced dikes and embankments built along flood-prone rivers and canals to contain high water. Irrigation and transportation canals also served as drainage ditches in low-lying areas of the countryside, directing excess rainwater into lakes which could be used as reservoirs. In the 20th century, hydroelectric dams brought further improvements in flood control in some areas. Nevertheless, many Menghean climate scientists have expressed concern that anthropogenic climate change will result in more intense rainy seasons, causing more severe floods upriver in addition to rising sea levels along the coast.

Typhoons

Much of Menghe's summer monsoon rain comes in the form of typhoons, which sweep westward over the warm waters of the South Menghe Sea before curving northward onto Menghe's southern coast. In rare instances, typhoons may even enter the East Menghe Sea, though this is rarer, as the mountainous coastline tends to break them up en route. As with seasonal rainfall, there is growing domestic concern that warmer surface temperatures in the South and East Menghe Seas are contributing to more powerful typhoons and a longer typhoon season.

Human geography

Population distribution

Menghe's population is densest along the coastlines and along the lower sections of major rivers. Historically, waterways were the only cost-effective way to transport bulk goods, and all Menghean cities developed in areas with some minimal level of water transport. Agricultural yields also led to variation in population distribution, with the central basin and Chŏllo plain supporting the most people on sophisticated farming and irrigation systems. By contrast, Suksan and Sanhu provinces support fewer people, while the Dzhungar Semi-Autonomous Province is only sparsely populated.

During the 20th century, and especially from the 1990s onward, Menghe's demographic center of gravity has shifted away from the central basin, as citizens migrated to coastal areas seeking industrial work. Although Menghe no longer has any special economic zones - their policies were applied nationwide in the early 2000s - major coastal cities like Sunju, Haeju, and Donggyŏng still offer better access for cargo ships, and have seen faster job growth than former inland cities like Hwasŏng and Junggyŏng.

Even as it worked to house the growing urban population with an ambitious public housing initiative, the Menghean government has also made an effort to control the pace of rural-urban migration with a household registration system. The NSCC has repeatedly pressed for household registration reform, and in 2018 the Menghean government laid out a timeline for removing barriers to residency changes.

Ethnic groups

The largest ethnic group in Menghe is the Meng, who make up 88% of the overall national population and 97% of the population outside the Semi-Autonomous Provinces. In the past, regional variations in Meng culture were recognized as distinct ethnic groups - Chŏllo and Suksan, for example, were identified with different dress and customs, as was North Donghae. It was only in the 1920s that "Meng" was formally expanded into an umbrella term for all Menghean natives not part of other designated minority groups, not just as a designator for people living in the Meng river basin.

Official Menghean statistics recognize six other "native minority groups." The Uzeris, Argentans, Daryz, and Siyadagis live in the southwestern region of Menghe, and all are predominantly Shahidic, while Sindoism and Chŏndoism predominate among the Meng. The Ketchvans and Dzhungar, native to northwestern Menghe, are two historically nomadic groups which lived at the boundaries of Menghe's political control until the 20th century. Each of these six mative minority groups has a Semi-Autonomous Province in its name, with partial autonomy in policymaking relating to culture, education, and resource use. Gangbuk Ketchvan SAP, the most recently-formed of the six, has two metropolitan cities and one prefecture which are majority-Meng, with reduced cultural autonomy.

Internal migration has led to a great deal of demographic mixing in Menghe, bringing together people from distant regions of the country. This mixing actually began in the 1950s, with an emergency PCOM policy that relocated urban residents to rural areas, and it has contributed to greater homogeneity in the Meng ethnic majority. The last few decades have also seen large-scale migration from the rural Southwest to Meng-majority cities, a historical first, and Meng migration in the other direction. MSP doctrine formally teaches that all ethnic groups are equal and deserve equal cultural rights, and discriminatory or secessionist language is outlawed under national law, but tensions between Meng and Shahidic-majority groups in particular have risen in recent years, especially as cross-migration leads to greater mixing of populations.

Administrative divisions

Menghe is divided into thirty first-level adminsitrative units. These are composed of twenty provinces (도 / 道, do), six semi-autonomous provinces (준자치도 / 準自治道, jun-jachido) or SAPs, and four directly-governed cities (직할시 / 直轄市, jikhalsi). The current provincial boundaries were finalized in 1968, through modifications to earlier provincial boundaries. Groups of provinces form Menghe's eight regions: Mengjung, Chŏnsan, Sansŏ, Mengbuk, Donghae, Dongnam, Chŏllo, and Sŏnam. Regions do not have executives, legislatures, or other local government organs, and are mainly used for administrative purposes by national-level bureuacratic bodies.

Below the provincial level, there are three more levels of administrative divisions. Third-level divisions are either Prefectures (현 / 縣, hyŏn) or Metropolitan Cities (도시 / 都市, dosi), with the latter controlling a broad swath of surrounding rural land. Fourth-level divisions are either Counties (군 / 郡, gun), in rural areas, or Districts (구 / 區, gu), in urban areas, with local names for each in Semi-Autonomous Provinces. Fifth-level divisions, the lowest of all, are called Blocks (면 / 面, myŏn) in urban areas, Villages (리 / 里, ri) in rural areas, or Gaja (가자) in parts of the Dzhungar and Gangbuk Ketchvan SAPs.

Land use

Environment

Rapid economic growth in the wake of Menghe's far-reaching reforms has placed heavy strain on the environment, adding to existing environmental pressures from prior industrialization efforts in the 20th century. Air pollution is an especially serious issue, with emissions of carbon dioxide and particulate matter steadily increasing from 1988 to the present. While the Menghean government made aggressive moves to promote nuclear power, most of Menghe's electricity production still comes from its abundant coal reserves, often in facilities with low-grade equipment. Increased car ownership has also contributed to smog in major cities, as has a surge in the production of steel, glass, and concrete.

In the countryside, high-intensity farming and changing rain patterns have intensified soil erosion and desertification, particularly in the Sansŏ region. Drought conditions have worsened, though due to increased agricultural productivity, better distribution infrastructure, and reduced trade barriers, Menghe has not experienced a famine since regime change in 1987. This high productivity has required the highest per-acre pesticide and fertilizer use rates in Septentrion, fueling concerns over food safety and sustainability, especially as water pollution and soil pollution eat away at arable land.

In response to serious enviromental problems, the Menghean government recognizes the threat of climate change and has taken increasingly ambitious steps to control pollution. Generous subsidies and research efforts have made Menghe a key player in efficient energy technology, driving steady cost reductions in wind and solar production while leading cutting-edge research into alternative forms of nuclear power. Nevertheless, Menghean carbon emissions are projected to continue to rise in the next ten years, driven by economic growth and rising consumer spending.