Acrea

Kingdom of Acrea Kongeriket Nordrige Königreich Nordrige Royaume du Nordreyar | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Stöðug í tryggð" Elder Nordic: "In Loyalty Steadfast" | |

| |

| Capital | Rena |

| Official languages | Nordic Gothic Venetian |

| Demonym(s) | Acrean |

| Government | Federal Constitutional Monarchy |

• Monarchy | Leo II |

| Emma Valen | |

| Legislature | Riksdag |

| Area | |

• Total | 3,376,982 km2 (1,303,860 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2020 census | 170,849,563 |

• Density | 50.6/km2 (131.1/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | ƒ12,813,717,225,000 |

• Per capita | ƒ75,000 |

| Gini | 29.6 low |

| HDI | .929 very high |

| Currency | Mark (ƒ) (ARM) |

| Date format | dd-mm-yyyy CE |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +62 |

| ISO 3166 code | ACR |

| Internet TLD | .ar |

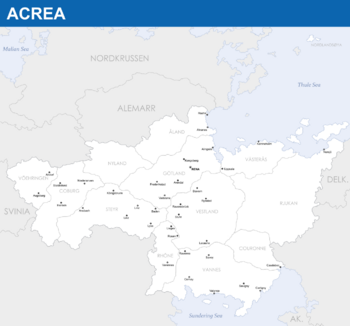

Acrea (Nordic and Gothic: Nordrige, Venetian: Nordreyar), officially the Kingdom of Acrea, is a country in Central Eracura, bordered by land to the west by Svinia, to the north by Alemarr, and to the east by Delkora. Its northern shore borders the Gulf of Åland, which opens to the Silent Sea while its southern coast borders the Gulf of Seyne, which opens to the Sundering and Bara Seas. Acrea has a diverse landscape, spanning from a warm mediterranean coast in its far south blending into a continental inland climate with lush forests, rolling hills, and snowy alpine mountains. Acre is the largest nation in Tyran by land area, with all of its territories encompassing over 3.7 million square kilometres. Its capital and largest city is Rena.

Since the Bronze Age, Acrea's primary inhabitants have been various Nordic tribes which originated in northern Acrea in what is modern-day Götland and Daneland. Ancient Acrea was one of Tyran's major cultural and economic centers, being one of the most important contributors to science, philosophy, and the arts in the ancient world. Cities such as Acre (modern-day Rena) and Ravenna are some of the continent's oldest continuously inhabited settlements, and served as nexuses of trade and travel in the region with their strategic positions along the Åare and Serre rivers. The rise of Acrean city states precipitated the rise of the Acrean Empire in the 3rd century BCE, which came to conquer and dominate the Eracuran continent. This influence led to the Nordicisation of many territories subjugated by Acrea, which was most prominent in far eastern provinces in modern-day Shalum and Æþurheim, and led to ethnic conflict with the slavic-dominated provinces of modern-day Svinia. The Empire would last as a unified political entity until Acrea fell into a brief civil war in 980. Rena won the conflict in 1016 under the war leadership of Erik Vaekarsson, but saw the old imperial dynasty deposed under the threat of a second coup and Vakaersson installed as king as Erik I. Acrea endured a politically turbulent period during the era of the Diarchy from the 11th to the 14th centuries. The system of government established under the diarchy divided political authority between the monarchy and the culminated in another series of major civil wars in the 14th century during the Acrean Wars of Succession. Acrea returned to a unitary monarchy under the Drage dynasty following the conflicts. The transition back to a strong central monarchy was led by a series of major reforms during the Ivorian Era of the late 14th century, which sparked a revitalisation of Imperial-era philosophy and ideals known as the Acrean Reformation. The Acrean Reformation had its roots in social and political philosophical developments made during the Wars of Succession and led to an explosion in liberal arts, science, mathematics, civic development, and economic development. The Reformation also led to a more imperialist attitude amongst Acrea's ruling classes; overseas conquests began during the Reformation, with both Serikos and Auroa coming under Acrean control. This period also formed the basis of Acrean-Aethurian and Acrean-Svinian enmity, which would come to partially dominate the continent's geopolitics for the next several centuries. Longstanding geopolitical conflicts in Eracura came to a head during the Great Eracuran War. Acrea and its allies emerged victorious from the war, establishing Acrea as the dominant continental power for a time and beginning a new era of relative peace in Eracura that persisted until the 2010s with the outbreak of the Midsummer War. Global Acrean influence grew in the postwar period as it became entrenched in Sidurian conflicts in support of its close ally Ruvelka.

Today, Acrea's size, favourable location for trade, and endowment of natural resources has allowed it to grow into Tyran's largest economy, and a leader in industrial, scientific, and technological sectors. Significant progress and expansion in new industrial technologies from 1730 to 1860 established Acrea as an industrial power, and a pioneer in technologies such as the steam engine and later automotives and aviation. Industry still constitutes a key part of the Acrean economy, with a major manufacturing and export sector focused around advanced manufacturing, technology, automobiles, and aircraft. The establishment of the Royal Exchange in Rena in 1567 laid the foundation for Acrea's modern financial industry, which grew rapidly after the Royal Exchange became the Rena Stock Exchance (RSE) in 1792, establishing a substantial post-industrial services segment of the modern Acrean economy. Acrea persists as a regional leader in several industries, particularly automotives, technology, electronics, defence, and energy. The Acrean government's extensive investment in renewable energy technologies has put Acrean energy firms at the forefront of this industry as pioneers in the production and use of renewable energy, with just over 45% of the nation's energy needs met via renewable energy sources in 2018 Oil, natural gas, and energy account for a large volume of Acrea's exports. Acrea is a developed high income country, and offers robust social security and universal healthcare systems, environmental protections, and low-cost university education.

History

Acrea is considered one of Tyran's cradles of civilization, being one of the first major cultures in the region with a major historical social, cultural, and economic impact on the Eracuran continent. The first Acreans were a diverse set of tribes split between the major ethnolinguistic groups; the Nordics originating in northern Acrea, and the southern Venetulani and Lucani, residing amongst and south of the Aarau mountains. Archaeological evidence points to a long history of friction and conflict between Venetulani and Lucani tribes, which was greatly exacerbated starting in 3000 BCE with the Nordic migration southward. Conflict with the Nordic peoples were split along ethnic lines, as Venetulani clans openly cohabitated, traded, and intermingled with newly arrived Nordic peoples in the south. and displaced the Lucanians, forcing them further east. Those that remained intermingled with the new southern Nordic tribes who gradually began to integrate their customs, culture, and language.

Archaic Era

Acrea's archaic period is generally thought to have begun around 900 BCE. By the end of the bronze age, numerous significant cultures and city-states had formed across Acrea, primarily focused around the Åare river in the north and the Serre river valley in the south. The cities of Acre and Ravenna were founded in these regions during this time, and were able to leverage their access to Eracuran waterways to establish persistent trade routes. While the north remained relatively insulated, contact and trade with the Sabrians gradually increased in the south over this period. The Old Latin-speaking Nordic Venetulani tribe rose to prominence from their strategic position in the Serre river valley, where they controlled most of the river trade between northern and southern Acrea. Over this time period, the increase in power of Acrean city-states led to different political entities consolidating as tribes joined together to leverage their collective strength. By the start of Acrean antiquity around 400 BCE, four consolidated cultures dominated Acrea: the Svaíar, Danír, Gothír, and Venír.

First Acrean-Sabrian War

The shift from the archaic period to the start of Acrean antiquity in Acrean historiography is usually marked by the outbreak of the First Acrean-Sabrian War around 400 BCE. Although usually described in the singular, the war was in fact a series of conflicts fought between the Sabrians and an ad-hoc alliance of Acrean groups throughout the 5th century BCE.

The Acrean Empire achieved stability through decentralised rule; it managed its vast territory through the appointment of Statthaltern, who were the locally-appointed governors of provinces throughout imperial territories. Several provinces would be combined into a region, frequently named for its most predominant local group, who would be overseen by an Acrean-born regnant. Though the empire maintained a standing army, security would be handled by local guard troops, similarly raised and paid for by the province. Taxation was often decided by a province's Statthalter, which rates related to the wealth of a given province. Though there were several attempts by Emperors to enforce a more rigid, centralised scheme to tax imperial territories, they were nearly always prevented by the senate. Perhaps the longest-lasting and most prominent feature of the empire, which would go on to be its most important legacy, was the vast network of trade and infrastructure that flourished within imperial borders. Large construction projects saw roads be built to connect far-flung corners of lands under Acrean control, and along with it the ability for merchants to move large stocks with no concern for extra taxes or legal complications.

Decline of the Empire

By the beginning of the 8th century CE, competition amongst regional rulers and major internal political strife plagued the Empire. A prominent effect of Acrea's longstanding nurturing of trade was the rise of numerous political within Acre, often tied to large families not just of noble descent, but of wealthy merchant background. Unlike before, these families did not just reside in Acre but across Acrea itself, providing greater power to regional rulers than had ever existed in Acrea previously. The broad decentralisation of power had grievous ramifications for the Empire. Strong control of the Empire had formed the basis for Acrean power across the expanse of Eracura for centuries. Effective and centralised civil and martial institutions had enabled the Acreans to efficiently and securely. The breakdown of these institutions precipitated a breakdown in Acrean control over its western territories, as well as the degradation of its military. This came to a head with the outbreak of the First Sundering War and subsequent conflicts, which saw numerous Acrean defeats in the west on Eracuran soil.

The decentralisation of power and the Sundering Wars led to the loss of control of Acrea's western territories. Although the lands of modern-day Svinia had been relatively peaceful, war caused widespread destitution, chaos, and disorder while decentralisation made it far more difficult to muster the strength to enforce order. Compared to the Empire at its peak, the use of professional soldiers was at a low point, with the use of regional levies in place of the concentrated, centrally controlled legions of the past. Although not of the quality of earlier legions, these levies remained effective soldiers; thanks to a longstanding warring culture, fighting and training to fight had become ingrained within the daily life for Acrean men. The technical skills to fight were widespread among Acrean levies but they lacked the standardisation of high-quality equipment and central command that Acrean legions of the past were known for. Varying levels of wealth from their regional rulers meant that there was no standardisation or large-scale production of particular arms and armour as in the past. Following the abandonment of Æþurheim, the loss of other territories came gradually. In a series of agreements in 865, 920, and 982 the territories of modern day Svinia, Nordkrusen, and Delkora separated from Acrea, marking the effective end of the Acrean Empire.

Viking Age

The first recorded events of the Eracuran Viking Age are a series of major raids along the coast of Symmerian Serikos in 742 CE. Although the practice of viking had long existed in Acrea, it had previously been practiced under the auspices of war or by known criminals, who would likewise raid trade and ports along the Acrean coast as well as foreign ones. By comparison, the raids of 742 were not only carried out by skilled warriors, but were largely ignored by any Acrean authorities (and in some cases ostensibly sanctioned due to the flying of banners).

Early Modern History

Ivorian Era

The ascension of Ivar III af Danneskjold as king in 1335 would prove to be a pivotal moment in Acrean history. Ivar III was educated from his youth; literate, and well-read in authors of all kinds from philosophers to historians, both foreign and Acrean. His understanding of the hierarchy of Acrean society led him to the conclusion that it was doomed to failure for the Crown, as the numerous estates and lands spread across Acrea's nobility were, in his view, fuel for personal gain over that of the Kingdom. Jarldoms, baronies, and counties existed independent of each other, each separated primarily by the amount of land which they occupied. Rather than the size of one's lands necessarily dictating their status, it was rather the wealth and power such land could bring them, and legal conflicts over resources and ownership was plentiful. Consequently, Ivar III instituted a series of major reforms beginning in 1358 to reconsolidate Acrean territory and reorganise noble society, creating the modern noble hierarchy which persists to modern Acrea. Initially a means of land ownership and hierarchical reform, his changes to the structure of Acrean territory proved to be useful for positively reforming governance.

Under the reforms, the traditional subordinate kingdoms of Acrea were formally restored as Archduchies (Acrean: Aarthertigdömen): Greater Götland, Daneland, Gothaland, and Venetia (also known as Vennesmark). Greater Götland was established as the Crown's archduchy, under royal governance as opposed to the archdukes and archduchesses which were to govern the others. Existing counties and baronies were consolidated into larger duchies, which replaced jarldoms. Definitions and importance likewise changed. Historically, all noble families of knightly rank were granted the title of Baron in a practice stretching back to the Acrean Empire. Under Ivorian reforms, this was changed. The rank of Baron and Baroness were separated from their association with military service though retained their connection to allodial governance of baronies (which were additionally abolished as a legal definition), and the ranks of Reiter and Kavalier formally created, with the latter in the same class as a Baron. The new hierarchical structure of the nobility not only established clear ranking by title among Acrean nobility where it had not existed previously, but also a formally defined system of governance for the nobility to follow alongside that which existed for non-nobility. Due to their closeness and familiarity with localities, Barons became the predominant nobles within the Riksdag, whilst Counts and Dukes remained more concerned with regional matters. The reforms additionally created ranks outside of this hierarchy- those of Royal Princes and Princesses, and Royal Counts and Countesses. These titles did not officially correspond to any distinct land holdings, and were instead indicators of status and favour as they answered directly to the monarch.

Among the most important of Ivar III's reforms was increasing the status of the Electors. Directly elected by the Landtag from the nobility, Electors are the only members of the nobility permitted to cast votes for the affirmation of a new Chancellor. With the Ivorian reforms increasing the closeness by which noble and non-noble governance worked together, the importance and prestige of being an Elector drastically increased, and is today still considered an immense honour.

Aside from immense reforms to the nobility, Ivar III oversaw substantial changes to other aspects of Acrean society with particular attention to education. His educational reforms focused on two goals he considered key; first was increasing the standard of literary, academic, and religious education across the kingdom, establishing rural schoolhouses for the children of agricultural workers to allow them education opportunities equal to those in cities and towns. Much like public schoolhouses in urban areas, these schools were opened and operated in close cooperation with the Storaasurshof, as the Temple not only was able to devote the necessary funding to their maintenance but provide highly literate priests and priestesses as educators. Access to such highly literate educators was what enabled the introduction of classical curriculums for pupils in these schools. The second goal was the creation of centralised trade schools, funded by the state. These trade schools allowed the formalisation of teaching methods and the creation of networks of tradesmen and apprenticeships, not only enhancing the education of aspiring trades workers but enabling other reforms in the areas of working and product standards.

Acrean Reformation

Ivar II's reforms were coupled with investment in industry and agriculture, and an increased awareness of the noble court to prominent inventors and tradesmen. The social and economic impact brought by Ivar I's reforms persisted well after his death in 1374 was marked by key inventions, such as the movable-type printing press in 1381. The social and economic development which immediately succeeded Ivar II's reign is known as the Acrean Reformation, a name attributed to Acrean philosopher and historian Lars-Henrik de Courcy in 1556. The term broadly covers the period in Acrea from the end of the 14th century to the beginning of the 17th century, during which Acrean culture was characterised by an effort to reintroduce and modernise ideas from antiquity as the center of contemporary Acrean society.

Leopoldine Era

Although founded in 1432, the Acrean Army traces its modern traditions to 1630 and King Leo I's martial and social reforms. The Leopoldine Era, in contrast to the Ivorian Era which came three centuries before it, was centered around power rather than the uplifting of society. Although a boon to the Kingdom, the social reorganisation of the Ivorian Reforms and economic prosperity of the Reformation brought a fundamental challenge to Leopold IV in the form of social conflict between a still-growing middle class, and the lower noble Junkers. Distinct from the middle and upper classes of the population, as well as from the higher titled nobility, the Junkers constituted their own tightly-knit group of elites who sought to maintain their growing economic dominance at the expense of the high nobility, as well as the middle- and upper-classes.

As the direct owners of much of Acrea's farmland and arable estates, the Junkers had been important in the raising of Acrea's standing army during the late Ivorian era. However, even by the early 1600s this force was still primarily composed of mercenaries in national service, alongside a small core of Acrean soldiers dedicated to the Crown. This force was both wholly unique and inadequate; the steady pay and merit-based hierarchy of the small professional army meant that military service was a genuine and desirable career option for Acrean men, just as the Empire's Army had been a millennia before. At the same time, it was too small to provide Leopold IV with the force that he needed to enforce his power, as mercenaries still provided the Junkers with the ability to create an army of credible threat to the Crown.

Although he and the high nobility possessed the power to take the wealth and estates of the Junkers, Leopold I was aware that using his power so tyrannically would undoubtedly lead to a very unhappy and potentially rebellious class of lower nobles, who would still possess considerable resources or could outright refuse the Crown's demands. The solution came from Donatien de la Serre, Comte du Villefranche-sur-Mer, a nobleman from Acrea's south. The son of the Archduke of Venetia, de la Serre's solution was termed the Sursis or Friste. In exchange for the payment of a huge sum to the Crown, the King would allow Junkers the ability to rule their estates without direct interference from the Crown or their high nobility.

The Friste was a success, and in turn Leopold I used this newly centralised bounty of wealth to re-acquire power and resources from the Junkers and upper class landowners. He first targeted the weaker and more rebellious of the Junker families; with each, they were stripped of much of their wealth, which was subsequently re-invested back in the growth of the army, until it had grown so powerful that the strongest of the Junker families did not need to be physically confronted or challenged to fall in line.

To a lesser extent, the Friste was extended to the high nobility as well. However, in compensation, Leopold generously offered positions and postings within the government and the new army. These positions were not only well-paid but prestigious, reflecting the high opinion of the new, wholly professional army under the Crown's command. For those Junker families who had not engaged in conflict with the common people or treasonous behaviour, they were offered lower positions. Through these actions, Leopold I successfully tied the well-being and success of the nobility to the state and the Crown. Thus, anyone who was anyone in Acrean society then had an interest in the well-being of the state and, by extension, the army.

With the goals of the Friste completed by 1644, his attention turned to reform of the army which although vastly expanded in size and repute, still followed the model of the Ivorian professional army that was now two centuries old. The army was, for the most part, considered the bastion of what became known of "Acrean Virtues"- traits such as discipline, loyalty, and modesty which had often been quite literally beaten into the men of the army. An army which, Leopold is noted as having observed, was inefficient for a continental power of Acrea's size. In 1648, he instituted the levy, or Landwehr, system. The Landwehr system was the first organised system of conscription in Acrea, and was created with the purpose of not only increasing the number of soldiers available at any given time, but also providing an immense, deep reserve of military-trained men which could be called upon in times of war. The reforms stipulated that all able-bodied men were required to serve at least two years under standard beginning at any point from their nineteenth to their twenty-third birthday, formed into Landwehr regiments which were based locally in the areas from which their manpower originated. These regiments would serve in support of the regular professional army, and would receive training equal to the regular army with the only fundamental difference being their shorter time of service.

The introduction of the Landwehr system was a balancing act for Leopold, but one which proved successful. Numerous changes had to be made to the way in which the army was run and trained, which are often referred to along with the creation of the Landwehr as the Leopoldine Reforms. Punishments were changed from physical ones to jail time and additional intensive drill. Likewise, prospects for advancement into the officer corps were made far, far better for individuals from any strata of society. These changes, combined with the existing prestige and socioeconomic prospects the army could offer, led to a drastic increase in the number of recruits for the professional army. The Landwehr is attributed with being the organisation that gave rise to the idea of "Acrean Virtues", as with the vast majority of men throughout Acrea spending time in the military, the population was gradually infused with these same virtues which came from martial education.

Geography

Acrea is the largest nation in Tyran by land area, with a total land area of 3,721,060 km². The majority of its territory is within continental Eracura, and it has several islands including the Marseillan Islands. Acrea's landscape is dominated by its varied climate and prominent mountain ranges. Two major mountain ranges run through Acrea: the Nordryggen mountains in the north which run along the border of Vännasö and Östergötland, and the Aarau-Voers mountains in the south which run along the border of Östergötland and Côte d'Or.

Climate

Running from north to south, Acrea has a varying climate owing to large shifts in elevation, mountain ranges, and the relative features of the northern Thule Sea and southern Sundering Sea. The Nordryggen and Aarau-Voers mountain ranges provide successive buffers the further south one travels. Northern Acrea, above the Nordryggen range, has a warm summer humid continental climate with the hottest summer temperatures scarcely exceeding 28°C.

Government

Acrea is a federal constitutional monarchy. Balance of power within the government, the limitations on the monarchy, and guaranteed rights of citizens are enshrined in a constitution called the Basic Laws of the Kingdom of Acrea (Kongeriket Nordriges Grundlagar). The Basic Laws were first codified as a single document in 1760, but fundamentally are a culmination of several landmark documents and laws created over centuries. They are divided into four main sections: the Instrument of Government (Regeringsformen), Instrument of Rights (Rättigheterformen), Instrument of Succession (Successionsformen), and the Instrument of Law (Domstolsformen).

The Instrument of government outlines the fundamental law which establishes the Acrean government. It describes the requirements of various offices as well as the basic limitations on those offices, as well as provides for how Parliament and the Monarchy work together to govern the nation. The Instrument of rights serves as a bill of rights, establishing the fundamental civil rights of Acrean citizens: these include freedom of press, freedom of assembly, freedom of expression, right to trial, and right to petition among other guarantees.

Acrean democracy is representative, with a unicameral parliament called the Riksdag. Initially, Acrean parliament was bicameral with two: the Riksdag and the Folketing. The Riksdag, composed of titled elected representatives including nobility called Electors, was the smaller and senior house of the legislature. The Folketing was the larger lower house, composed of common elected representatives. Aside from a difference in title, representatives between the two houses also serve different levels of constituency. The Riksdag served to review and revise legislation proposed and passed through the Folketing, had the ability to delay final passage of legislation by the King or Queen in order to present it for reconsideration in the Folketing, and could submit its own legislation for consideration. A major parliamentary reform in 1792 combined both houses into a single chamber as the Riksdag. The Chancellor, the head of parliament and the government, is effectively elected by agreement amongst the party or coalition of parties selected to form the government.

Law Enforcement and Security

Policing within Acrea is centralised, with the National Police (Rikspolitie) being the largest and most prominent police force under the Ministry of the Interior. The National Police operates divided by provinces, and is then further subdivided into districts. Primary police markings are dictated by region- officers in Daneland will wear equipment marked Politie or Polis, those in Gothaland are marked Polizei, and those in Venetia are marked Police. The Rikspolitie is subdivided into departments which can serve up to several local municipalities.

Proper national-level policing and security is organised under the Ministry for Internal Security (MIS), which is not a government ministry but rather an agency which is a component of the Ministry of the Interior. MIS is Acrea's predominant intelligence agency, and coordinates the efforts of the entirety of Acrea's non-military intelligence community. MIS has two subsidary agencies, the National Security Service (SAPO) and the National Intelligence Service (ONI). SAPO serves as a special security and intelligence service, focused primarily on counter-espionage, counter-terrorism, and counter-intelligence operations. It closely coordinates with ONI, which is focused on foreign intelligence and foreign clandestine operations. SAPO also works closely with the Rigspolitie to engage in crime prevention.

Military

Economy

The Acrean economy is a mixed model economy; it combines a broad free market with substantial state ownership and participation in key industrial sectors of the economy, and has been described as a capitalist welfare state. It benefits from a highly skilled labour force supported by an extensive and thorough vocational education system alongside its university education system, which is all held up by Acrea's generous social and welfare infrastructure which supports universal single-payer health care services, universal affordable higher education, and benefits such as guaranteed substantial paid parental leave. Acrea has a moderate birth rate but relatively low immigration rate, related to strict immigration requirements. Major sectors of the Acrean economy include energy, complex manufactured goods, pharmaceuticals, automotives, and defence exports. Acrea is richly endowed with natural resources that are protected under comprehensive environmental and climate laws; these regulations put practical constraints on Acrea's agricultural sector, which is not as major of an export sector of the Acrean economy and largely serves domestic demand. Manufactured goods, automotives, and energy are the major export sectors for Acrea.

Manufacturing

Complex goods and advanced manufacturing form the pillars of Acrea's manufacturing sector. Machine equipment and robotics (especially medical equipment), technological components (such as semiconductors and advanced chips), appliances, automobiles, aircraft, and pharmaceutical goods constitute Acrea's manufactured goods that are critical to its export market.

Energy and Natural Resources

Energy is one of Acrea's most important sectors, and a key area of investment for the Acrean government. A net exporter of energy, the bulk of Acrean electricity is produced with nuclear power. An early adopter of nuclear energy, Acrea's first power-generating nuclear plant began operation in 1954, with the first full-scale nuclear power station following in 1955. The large-scale adoption of nuclear power served more than one purpose; in addition to being a cleaner source of energy, it also allowed Acrea to prioritise its large sea hydrocarbon reserves for export. Beginning in 1990, the Acrean government embarked on an energy diversification program, looking to phase out hydrocarbons completely for large-scale power generation. This diversification effort focused primarily on wind and hydro power, with solar power considered a secondary source. A renewed effort with more ambitious goals was started by Chancellor Hans-Christian Sørensen in 2005. This effort aimed to completely phase out the use of hydrocarbons by 2025, and achieve a 50/50 mix of nuclear and renewable energy by 2030.

In 2020, the breakdown of energy production was:

- Nuclear power (57%)

- Renewables (43%)

- Hydrocarbons (1%)

Oil Industry

Acrea's hydrocarbon industry grew rapidly from the first tapping of offshore oil reserves in the late 1960s. Production of natural gas and oil had taken place since the mid-19th century, but Acrea possessed few underground reserves. The first discoveries of offshore reserves in the Thule Sea didn't occur until the early 1960s. It took until 1967 for the first offshore wells to begin construction into vast offshore reserves. The project was met with considerable opposition despite the opportunity; fishing has long been an important part of Acrea's agricultural sector, and was threatened by the risks of offshore drilling. Under pressure from the fishing industry, the Acrean government passed very strict safety, maintenance, and oversight regulations for the oil industry in 1969 which initially slowed the industry's growth. By 1976, however, Acrea became one of the region's largest oil-producing nations, with most of Acrea's oil production controlled by the state-owned Nordic Oil Corporation.

Demographics

Ethnicity

The concept of ethnicity in Acrea is ostensibly complex to an observer, owing to its size which results in rich cultural and linguistic diversity. Acreans today generally identify with one of three main ethno-linguistic groups: Danes, Goths, Venetians. These are derived from the four Nordic cultures which occupied ancient Acrea; the Danír and Svaíar of modern-day Daneland and Götland, the Gothír of modern-day Gothaland, and the Latin-speaking Venír of modern-day Venetia. The Hellenic Arcaneans, who most commonly identify as Venetian, are the only non-Nordic ethnic group native to Acrea, as descendants of the mass migration of hellenic peoples from Kydonia who settled in modern-day Venetia in pre-antiquity.

Since the early modern period, identification with different ethnolinguistic groups has been replaced by a singular Acrean ethnic identity, simply subdivided amongst various regional cultural identities. Although integration amongst Acrea’s various groups had been a matter of policy since antiquity, the end of the Wars of Succession created a new period of even stronger cultural amalgamation. Inversely, a solidified single Acrean ethnic identity also led to traditional inclusivity turning into exclusivity.

Current academic consensus among anthropologists argues that a single Acrean ethnicity existed even prior to societal consciousness of it in early modern Acrea. Syaran anthropologist Dr. Zdravko Dragomirov Pironev, who began discourse on the topic in 1988, was one of the foremost foreign proponents of the concept of an earlier single Acrean ethnicity. Gylian anthropologist Dr. Rueda Lasfæ further supported Pironev's proposal, agreeing with Pironev's four identifying traits which support the classification of a single Acrean ethnic group that existed at least as early as late antiquity:

- A common history which distinguishes it from other groups.

- Shared cultural traditions, including both social and family customs.

- A common religion which distinguishes it from neighbouring groups.

- A shared language, owing to the common use of Nordic in all parts of Acrea.

Consequently, the Acrean government traditionally does not distinguish between ethnicity amongst its own native-born citizens during a census, considering all Acreans with predominantly Dane, Goth, Venetian, or Arcanean ancestry as Acrean. It collects ethnographic information from foreign-born residents within Acrea as well as their descendants. As of the 2020 census, 93% of the population was Acrean with 7% having immigrant background. Moravians, a slavic ethnic group from the border regions of Acrea and Svinia, constitute the largest non-Acrean ethnic group in the nation, with Shalumites and Quenminese close behind. Due to the economic devastation in Shalum during the war, large numbers of refugees and job-seekers migrated to Acrea in search of work and economic well-being. Significant numbers of Shalumite women also immigrated to Acrea after marrying Acrean soldiers who had fought in and occupied Shalum after the war. Extramarital relations between Acrean soldiers and Shalumite women proved substantial enough that the Acrean government instituted a birthright policy in 1965 which allowed migration of children born as a result of these affairs to migrate to Acrea, and which still exists today. Quenminese immigration has held at a high rate, but was especially significant in the late 19th and 20th century where many migrated to Acrea to pursue new educational and economic opportunities.

Settlement of much of the continent by Acreans has led to several states in Eracura tracing their lineage back to Acrean settlement of their current territory. This is especially prevalent in the cases of Nordkrusen, Æþurheim, and Delkora, both of whom attribute settlement by Dane settlers as significant parts of their national formation. The prevalence of what could be considered Acrean ethnic groups in states other than Acrea has challenged the current mainstream definition of Acrean ethnicity, especially as centuries of efforts sponsored by Acrean rulers has led to the creation of a very strong Acrean national identity which would oppose the inclusion of foreign Nordic groups into the Acrean identity.

Language

Acrea is one of the most multilingual states in Tyran thanks to its size and unique national makeup. The Acrean government recognises three official languages: Acrean Nordic, Venetian, and Gothic. For official uses, any one of the three is accepted. Acrea's modern linguistic diversity is a consequence of its founding in antiquity which united the Norse-speaking North with the Latin-speaking south, and the equal importance of both languages in every iteration of Acrea's government since.

There is an extremely high rate of multilingualism amongst the Acrean population, for both practical and policy reasons. Beyond being a practical necessity of daily life in Acrea, language education is legally mandated. Language education is compulsory for all Acrean pupils beginning in kindergarten, and often by the secondary school level full classes are taught in a non-primary regional language of the region. Nordic classes are a requirement for all students, whilst Venetian and Gothic are optional but usually dependent on where a school is located. In addition to extensive linguistic education, Acreans are also heavily exposed to all three languages in their daily life through media.

Religion

Health

Culture

Sport

Athletics is intrinsic to Acrean culture as a consequence of cultural tradition as well as centuries-old royal and state sponsorship of athletics programs, leagues, and events across the country. Acrea's cultural affinity for sports is traced to the traditions of the Miðsumarsleikir, or Midsummer Games, and Jólsleikir, or Yule Games, a pair of festivals held once every two years (alternating) in the city of Uppsala to honour the gods Thor, Tyr, Aela, Freyr, and Freyja. The Miðsumarsleikir festival lasted from the holiday of Midsummer, in late June, until the first of August which was celebrated as Freyfest. The Games would begin one week after Midsummer and last until the end of July and featured a host of events. Events known to have been featured since at least 400 BCE included foot races (both sprints and long distance), javelin throwing, pentathlon, archery, boxing, wrestling, horse racing, and blunt weapon dueling. The popularity of the Games was such that victorious athletes became some of Acrea's earliest known celebrities.

Jólsleikir was held on a similar schedule, beginning one week after the celebration of Yule in late December and lasting until the end of January. Though smaller in scope than the summer Games, the ancient Yule Games featured events such as cross-country skiing, short-distance ski races, dog sled racing, ski jousting (in which competitors demonstrated the use of various weapons on targets whilst using skis), and ski archery.

Track and field, skiing, biathlon, and archery are sports considered to be traditional in modern Acrea. Competition shooting and archery form a key part of Acrea's national identity. Many parts of Acrea have a strong hunting traditions, which is built upon by competition marksmanship tied to local annual shooting festivals known as Skyttefestivaler (German: Schützenfeste, French: Festivals de tirs) which hold numerous competitions and are celebrated across Acrea. Shooting clubs are a frequent part of communal life outside of major cities in Acrea. Modern competition shooting, track and field, and combat sports are considered to be an evolution of similar practices during communal celebrations in ancient and medieval Acrea, where martial competitions such as axe-throwing, javelin-throwing, jousting, and fencing were common. These celebrations were often held in order to select competitors to represent a community at the Midsummer or Yule Games, if the community could afford it.

In the modern day, association football and Formula One racing are Acrea's two most popular sports by league revenue and number of spectators. Organised association football in Acrea is divided into five tiers, with the first three comprising a professional football league known as the Allnorskanliga. The fourth tier is the Regionalliga, which is a mixture of professional and semi-professional clubs, and fifth is the entirely semi-professional Föreningsliga. Acrea's governing football body, the Nordriges Fotballförbund, is the country's largest single-sport athletic organisation in Acrea with 15 million members.

Acrea has historically been a leading nation for motorsport as a hub of automotive design and manufacture. Formula and endurance racing are its two most popular forms of motorsport. Acrean motorsport is unique in that there are almost no spec series currently running, making each motorsport a competition not just between drivers, but between engineers and manufacturers as well. The Nordriges Motorsportförbund, or Acrean Motorsport Federation, is the country's governing motorsport body and oversees regulations for all motorsport within Acrea.

Cuisine

Acrean cuisine is well-known and renowned. It is often cited as the origin of modern restaurant service and haute dining. It is composed of a wide variety of regional and local cuisines reflecting Acrea's wide climate range, and its rich and diverse cultural history. Acrean cuisine is perhaps best known abroad for number of its exported staples; its wide array of cured meats and sausages, chocolate treats from its alpine chocolatiers, and its high quality and abundance of certain types of seafood. Acrea is also well known for its vast selection of alcohols. Beer, wine, cider, and mead are all incredibly popular throughout the country, with beer being predominant in most regions with the exception of Acrean Venetia, where wine is more popular. It is estimated that among Acrea's approximately 3,000 beer breweries, there are nearly 7,000 varieties of beer brewed in Acrea nationwide with a wide selection of regional varieties. While beer, cider, and mead breweries are located all over the country, wine production is centered primarily in Acrea's central and southern agricultural regions. A wide variety of wines are produced, many of which are considered unique to Acrea and protected by place of origin laws. The most common varieties of red wines produced are pinot noir and cabernet sauvignon, while the most common variety of white wine is riesling.

One of the earliest known Acrean recipe collections was the 6th century Um emnið att Matreiðsla (On the Subject of Cooking), written by Audo Evorikssen, a gourmet of the Late Imperial era. Later recipe collections and cookbooks from the 8th century onwards have provided culinary historians with a clear evolution and development of Acrean cuisine over time.

Beginning in the 1400s, Acrean society began to see the development of haute cuisine, distinguished from regular cuisine not by who could eat but rather in the nature of its preparation. Although dedicated chefs had existed since antiquity in Acrea, it wasn't until the establishment of the country's first dedicated culinary school in Baden in 1436 that truly professionally educated chefs became commonplace in the courts and estates of Acrean society. Culinary arts had long been considered a trade alongside those such as carpentry and masonry, however where these professions had long had their own dedicated institutions, culinary arts had not. Professional chefs quickly became a staple amongst higher society, with chefs taking up positions not simply as the head of their estate's kitchen but also serving as the individual in the household staff responsible for planning lavish events such as parties, feasts, and weddings. "High" cuisine became known as such because of the meticulous planning, deliberately selected ingredients, use of extravagant presentation, and complex cooking techniques which was used by these chefs.

Although only the upper class were able to truly afford exotic ingredients or the extravagance that professional chefs had become known for in Imperial Acrea, most aspects of traditional haute Acrean culinary techniques, flavour profiles, and presentation have long since trickled down to be widely accessible due to their pervasiveness within culinary education in Acrea. Like other trades, there was little cost associated with attending school, and so aspiring chefs of different socioeconomic backgrounds could attend, widely disseminating culinary knowledge across Acrea.

Folklore

Owing to the age of its culture and its strong religious traditions, Acrea has a deep and rich folkore. Acrean folk tradition is strongly linked to religious mythos, and as a consequence has directly influenced both religious practice and religious traditions in many parts of Acrean society. The pervasiveness and popularity of Acrean folklore has led to it spreading in many variations across Eracura, as well as across Tyran. Traditional Acrean folklore is derived almost entirely from sagas. Acrean sagas are classified into two types: the first type comprises religious scripture, and are collectively referred to as the Æsirsögur (often capitalised as Sagas to distinguish them from non-scripture sagas) . These sagas are definitive Asuryan religious scripture upon which strict religious tradition is founded. The earliest written fragments of these sagas date to ca. 1100 BCE, though they are believed to have originated much earlier. Some creatures and entities in Acrean folklore, such as the dragon or ghostly Disir, originated with these Sagas. The second type comprises religiously-adjacent stories, poems, and epics which although have decidedly religious themes and influence, are not a part of scripture. These sagas have a wide variety of dates of origin, but their enduring popularity among Acreans through centuries has led to them being an important part of Acrean folk tradition.

One of the most enduring and popular of these latter type of sagas is the Vampírunnarsaga, which gave rise to the legend of the vampire in Tyran and cemented such creatures as one of the most prominent in Acrean folklore. While many scholars point to the saga's literary excellence as one source of its popularity, as well as the mystery and mystique surrounding its subject matter, others also note the unique way in which the legend has been intertwined with other parts of Acrean society throughout the centuries. In one example, legends surrounding the venerated Templar Order were directly connected to the myth of the vampire since at least 100 BCE. Acrean, Makedonian, and Sabrian literary sources often contained common descriptions of Templars on the battlefield as fighting in a trance-like bloodthirsty state, during which they were said to have been unharmed by any weapon or element like fire.