Cassonne

The Seraphic Republic of Cassonne

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Capital | Citadelle Royán | ||||||

| Largest | Saint-Catherines | ||||||

| Official languages | Cassonnaise | ||||||

| Recognised regional languages | Pexio Arseneko | ||||||

| Demonym(s) | Cassonnaise | ||||||

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic with directional government | ||||||

• Chancellor | Eugène Thibodeaux | ||||||

• Collège du Conseil | Léonard Pasquier Laurent Berthelot Marie-Claire Beaudouin Anne Coulomb | ||||||

| Legislature | Parlement Cassonnaise | ||||||

| Senate | |||||||

| National Assembly | |||||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate | ||||||

• Per capita | $36,246 | ||||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate | ||||||

• Per capita | $23,132 | ||||||

| Gini (2020) | 28.5 low | ||||||

| HDI (2020) | very high | ||||||

| Currency | Franc (FCR) | ||||||

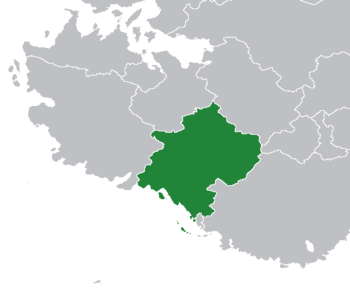

Cassonne, officially The Seraphic Republic of Cassonne (Cassonnaise: La République Séraphique de Cassonne; Pexio: República Serafí de Cassonne; Arseneko: Cassonnako Errepublika Serafikoa) and colloquially referred to as the Seraphic Republic, is a republic located on the South Teudallum continent of Astyria. It shares borders with Monsa and Alcantara to the south, Heideland to the north and Andamonia to the west. Its capital is Citadelle Royán, while the largest city is Saint-Catherines.

Although archaeological findings have shown that the territory has been continuously settled for ages, prominent artefacts prove the existence of settlements in the south and relations with the Mosetos, settled in the territory of Alcantara. The immigration flux from other territories of South Teudallum, the later contact with Hesperidesian merchants and the arrivals of Beriquois people, made the Cassonnaise develop forms of self-rule and a unique distinctive identity from other peoples in the area. The commercial relations and later the first Exponential settlements along the Cassonnaise coast brought modern forms of government and social structuration as well as the Catholic faith. For much of the middle ages, the territory would see the several disputes between self-proclaimed rulers and kings. As feudal kingdoms expanded their control, so did the discontent of the population, which lived under poor conditions and suffered the lack of governance. Stability would only come with the signing of the Treaties of Saint-Catherines and the partition of the territory, which started a period of direct control from Berique.

The end of the middle ages and the arrival of the enlightenment marked the start of a period of abundant production of literature, art and innovative political movements, that questioned the existing structures and the relation with Berique, among others. The period was crucial for the start of an independence movement that, although both saw an independent Cassonne as objective, later divided between monarchic and republican forces. In Berique, the fall of the monarchy created the right and needed circumstances for the explosion of their Cassonnaise counterparts. As Cassonne's monarchs involved in the Austral War with the Empire of Exponent, living conditions became incredibly inhumane for most of the population and the Principality of Cassone saw itself on the verge of the collapse. However, the monarchy remained in place, under different forms, monarchs and royal families, until the the republic sentiment became unstoppable. On May 19th, 1900, Alexandre Épouse Vivien declared the dissolution of the Seraphic Empire with the Château Floure Declaration that funded the new successor-state, the Seraphic Republic. Alexandre was declared the first Proconsul of the republic for the next 14 years. During July 1900, the young government also proclaimed the Accords de Liberté, which served as the first Constitution of Cassonne. Under the distinctive form of government of Cassonne, several political parties have surged since the mid-1800; however, Le Républicains and the Parti socialiste have formed most of the collective governments and dominated elections.

Cassonne functions as a Unitary semi-presidential republic with directional government, formed by four members that rotate every four years to occupy the presidency of the Collège du Conseil, the collective Head of Government, and a Chancellor, figure that serves as Head of State. The Seraphic Republic is an active player on the regional foreign relations and holds an important role on the south of Teudallum. It is member of several international organisations.

History

Cassonnian Gaul and the Mince Espoir (1794-1814)

Under the watchful eye and firm resolve of the Bourbons, Cassonne had developed into a prized colony of Gaul, rich in material resources and fertile land. The relative prosperity of the dependency may have played a role in its selection as the destination of Charles Philippe, the brother of King Louis XVI, during the collapse of the House of Bourbon in Gaul during the last decade of the 18th Century. With the royal family all but wiped out by 1795, and the authority of the Gaulic monarchs wiped out, Cassonnian Gaul found itself without a parent nation. While the colonial government largely remained unaffected in 1794 by the growing distress in the homeland, by 1795 it became apparent that the colony was being indirectly forced into independence. This upheaval triggered the fostering of democratic revolutionaries, notably Michel of Preixan (1752-1796), Jean Roy (1743-1796) and Daniel Burgoyne (1731-1802). With powerful members of the aristocracy pressing for more authority, and the general population pleading for liberalization, the colonial government found itself embroiled in the largest domestic crisis in its history. This instability was brought to bear during a political protest in August 1795, when revolutionaries under Jean Roy sought to instigate a public uprising in Nor'Calais, at that time the largest city in the colony. Charles Philippe, by this time already beginning to assert more direct control over colonial officials, takes up residence in the Palais Bleu in Citadelle Royán, and organizes loyalist forces to put down the uprising. Brief-but-bloody clashes between loyalists and revolutionaries culminates in the Siege of Puichéric between October 1795 and January 1796, when Charles Philippe's loyalists overwhelmed and destroyed Jean Roy's partisan army of democratic revolutionaries in the city of Puichéric.

The demise of the civil uprising after the capture of Puichéric symbolizes the end of the major democratic protests in Cassonne during this era, though democratic reform movements prominent at the turn of the twentieth century trace their roots to these initial uprisings. The turmoil of the age, combined with the surviving members of Gaul's Bourbon dynasty, symbolizes the Mince Espoir, or Forlorn Hope in Cassonne—a period where the country's very future was frequently called into question due to political instability and the threat of incursion from the Gaulic mainland by the revolutionaries responsible for the collapse of the Bourbon dynasty. Between 1794 and 1814, Cassonne's political organization was tenuous at best, with the colonial authority hastily converted into an independent kingdom under the control of Charles Philippe, who adopted the royal styling Emmanuel I, Dauphin of Cassonne. As the first regent of the newly-christened House of Rossignol in the colony-turned-monarchy, much of Emmanuel's reign was devoted to repurposing the colonial resources of Cassonne into the new government, a slow and tedious process that would not be completed in his lifetime. Emmanuel would die in 1801 during an outbreak of Yellow Fever in Cassonne. His son and successor, Louis Antoine—Dauphin Antoine—was incapacitated during the same outbreak, and would succumb less than a year into his reign, further fraying the already-weak hold of the new monarchy on Cassonne. At this time, the country was alternatively known as Gaulic Cassonne (in a reversal of its colonial name), the New Gaulic Kingdom and New Gaul, though the country was officially the Principality of Cassonne from 1796 until 1814. Louis Antoine's young brother Charles Ferdinand (Dauphin Ferdinand) fared no better than his predecessors had.

By 1812, the fledgling Principality of Cassonne was on the verge of collapse. Civil unrest was growing in the north, where citizens frequently felt abandoned by the government, which was consumed in its management of the more affluent south. An inflationary economy had already soured the long-term prospects across the country, and the troubles were compounded when Ferdinand impulsively declared war on the Empire of Exponent in March 1812 shortly before he succumbed to cancer. Ferdinand's only son, fifteen-year old Frédéric—the last living link to the destroyed Bourbon dynasty—assumed the role of Dauphin. Though many assumed that the young Frédéric would parlay for terms with the much-more powerful Empire of Exponent, the young Dauphin shocked everyone by prosecuting the war vigorously, using Cassonne's scant resources to their fullest potential through exceptional leadership. The conflict with the Empire of Exponent, immortalized as the Austral War, would last for just two years, but it was a watershed moment for the Principality. Frédéric's strength of character and remarkable strategic successes rallied the Cassonnaise in a way that had been impossible under his three predecessors. And although the result of the war was a strategic draw, the tactical implications were immense: Cassonne gained possession of the lucrative city-state of Valle Crucis, and emerged from its troubled origins as a burgeoning young power in Southern Teudallum. The stalemate was viewed as an emotional victory, and a divine miracle from God. Thereafter, Frédéric proclaimed his new dominion the Seraphic Empire, of which he would become its first Séraphin. Frédéric would rule successfully during the Grand Âge (Great Age), and was immortalized in death as Frédéric the Great, the Empire's best Séraphin.

The Seraphic Empire and the Grand Âge of Cassonne (1814-1886)

The country's successful prosecution of the Austral War against considerable odds prompted a surge in national fervor in the years following. Frédéric's reign was marked by relative peace and stability, comparative to the reigns of his predecessors. It was during Frédéric's Premier Mandat that an egalitarian tax structure was first approved, and significant investment into the nation's infrastructure was made. The newly-christened Séraphin also made Citadelle Royán's first overtures towards the Northern Préfectures, where democratic protests had persisted even into the postbellum period, working to establish the country's first public welfare system to help sustain the more agrarian north. Frédéric also appropriated considerable sums of money toward beefing up the military in building up the Empire's burgeoning navy, which had sustained moderate damage in the naval clashes with the Empire of Exponent.

Much of Frédéric's reign post-Austral War passed by peacefully and prosperously, leading to the coinage of the phrase Grand Âge, or Great Age to describe the Seraphic Empire's remarkable growth and stability during this period. The monarch's consideration of all social castes in Cassonne was a hallmark of the era's rulers, who expanded on the notion that all Cassonnaise subjects were deserving of attention in Citadelle Royán. When Frédéric died in 1844, his daughter Yvonne became the first female Séraphin in the Empire, and immediately sought to fund the construction of public universities to provide educations for poorer citizens. The progressive idealism of the age was encapsulated in Séraphin Yvonne's Édit sur le Privilège, an 1853 speech which decried the growing stratification of social classes and the disparity of wealth between the aristocracy and the poorest. Her heirs would come to disagree. At the zenith of the Seraphic Empire's power, the stability of Citadelle Royán was rooted in the strength of two successive Séraphins: Frédéric and Yvonne. By the end of Yvonne's reign however, public antipathy towards the progressive tax code had begun to mount, especially among the elites. Her son and heir, Emmanuel II would set about repealing much of the country's welfare system during his short reign, which was carried on by his brother Édouard I after Emmanuel's sudden death in 1869. Under Édouard, the country's military power reached its highest level, as the Seraphic Navy emerged as a preeminent power in Astyrian waters. The wealth disparity significantly widened during this period however, and civil unrest began to fester in much the same way that it had seventy years before. The political group Démocratie Maintenant, or Democracy Now held its first gatherings in 1874 in the city of Montclair.

Édouard's only daughter Melisent became Séraphin upon his death in 1875, helping to stabilize the growing unrest that had begun to develop. As Séraphin, Melisent sought to strike a balance between the policies of grandmother and those of her father by increasing domestic spending on public works and healthcare, while keeping the military's funding at record-levels. The strain on the nation's coffers led her to redraw the nation's tax code, realigning with Frédéric's original policies. The first nine years of Melisent's reign represented Citadelle Royán's apex as an Imperial power in Astyria, with a booming economy and the softening of civil unrest that had begun under her father's reign. A series of crop failures in 1884 however created significant shortages of food, which reignited protests against the monarchy. This blight would spread to Valle Crucis in 1885, furthering the increasing troubles that Melisent faced. In an effort to appease the increasingly-wary population, Melisent sought to utilize government spending to curb the crisis as she had at the start of her reign. This time however, the increase in spending led to a significant debt crisis in the country. Taxes raised sharply, prompting severe economic downturns in South Cassonne, leading to the Panic of 1885-1886. With a stagnant economy and powerful opposition voices beginning to rally people against Citadelle Royán, Melisent sought to implement the Seconde Mandat in 1866, which would have established constitutional checks on the monarchy in an effort to keep the country unified behind the throne. This incensed the well-to-do and certain members of the military, who had come to rely on the monarch's power to retain their own stations. In 1886, the rich would take measures that would bring about the end of both the Grand Âge and the Empire also.

A cabal of wealthy financiers and military leaders—who by this time had become well-ingrained in the country's trade empire—formed a secret organization known as the Restaurationnistes, or Restorationists, in order to try and 'restore' Citadelle Royán's absolute authority. At first, the movement was designed simply to check the Séraphin's platform and rally support against her. When Melisent began a country-wide speaking tour denouncing wealth inequality however, their goals became more sinister. With the complicity of the Séraphin's heir apparent and ultraconservative son Maxime, the Séraphin Melisent was assassinated in a coup d'état on August 25th, 1886 while traveling on holiday to Villesèquelande Préfecture. While in her carriage, her bodyguard Commandant Maurice Henry fatally stabbed her after a posse organized by the conspirators had besieged her. She was the only Séraphin to be assassinated.

The Decline of Cassonne's Empire in the Dernier Âge (1886-1900)

Though Melisent's reign had endured the most serious domestic challenges the Empire had faced since before the Austral War, her death was a considerable blow to the population, who had come to view her as an ally in the fight for liberty and freedom. Her martyrdom, and the public outcry against the apparent coup, signified a dramatic escalation in the public outcry against Citadelle Royán, and marks the official end of the country's Grand Âge. The ensuing period was marked by continued democratic resistance against increasingly autocratic mandates from Citadelle Royán, ultimately culminating in the arrest of a Séraphin and the final surrender of the monarchy a scant fourteen years later. This interruption between the Great Age and the first years of the Seraphic Republic has become known as the Dernier Âge, or Last Age of the Seraphic Empire, and a lost era of promise for Cassonnaise people.

The reign of Maxime was tainted by the inauspicious way in which he rose to power. Though proof of his participation in the coup to assassinate his mother was not found during his lifetime, the accusations were quickly leveled by protesters led by non-compliant members of Melisent's court, including Lord Alphonse of Auberon and Admiral Clément Trausse, who would go on to become two of the Seraphic Republic's founding fathers. Particular derision was cast from a meeting hall in the city of Montréat called Château Floure, which had become a rallying center for the country's young democratic movement. Maxime responded with brutal force, using the military to clamp down on protests, which by this time had begun to disrupt official business even in southern cities such as the aforementioned Montréat and Pradelles-Cabardès. The capital of Cahuzac, Ricaud was put under martial law due to a protest in 1891. The situation began deteriorating in earnest in 1893, when the second economic Panic in ten years, the Great Panic of 1893 further eroded what fleeting loyalty Séraphin Maxime still enjoyed from the general population. Unlike the recession of his mother, this Panic sparked a full-blown depression that was made worse by exorbitant spending on the military, which Maxime had initiated in order to buy off the loyalty of his generals, who themselves had begun to resort to desperate measures to keep the army in line. The practice of decimation was briefly instituted in 1894, and again in 1897 to prevent rebellion amongst the ranks. In the case of the former, the threat was enough to keep troops in line. In the latter case, the threat prompted an even greater backlash, resulting in its rapid repeal. Public reprisals against civilians remained however through the actions of a cadre of loyalists known as the Marteaux.

Despite the increasing violence on the homefront—or, perhaps because of it—Séraphin Maxime began to ratchet up the Seraphic Empire's military aggression in the region. These actions quickly led the Empire afoul of the Constitutional Monarchy of Aquitayne in 1888, who became a target of Maxime's aggression. Using drummed-up evidence that implicated Aquitayne's royals in fostering democratic revolution in Cassonne—a dubious, albeit controversial claim today—Séraphin Maxime became only the second regent of Cassonne to declare war. During the prosecution of the war itself, it was referred to by Citadelle Royán as the War of 1888, but historians have since come to label the six-year campaign as the Guerre de l'Usurpateur, or War of the Usurper following the revelation of his participation in the assassination of his mother. Despite Maxime's aim to wage a limited war, more than 100,000 died. Despite vague ideas over gaining territorial concessions from Aquitayne, the tactical stalemate which followed any marginal gains from the outset turned into a strategic defeat by the war's end. Faced with crippling public opposition to the war, and the military's own difficulty in maintaining order, Maxime was forced to accept what was to him a humiliating mediation in 1894. The terms of the peace treaty required the Seraphic Empire to cede autonomy to Valle Crucis within ten years, which the Seraphic Republic would honor in 1901. Though he claimed victory in the negotiations, the public and the military viewed the stalemate as a defeat, which weakened Maxime's prestige in the region. The Séraphin stewed bitterly over the loss, and by 1896 had convened a War Council in a vain effort to restart the war with Aquitayne. A massive heart attack ended these plans, along with his reign and his life in April 1896.

Maxime's inexperienced son Édouard II would succeed him to a Throne which was rapidly losing control. In the first year of Édouard's rule alone, more than twelve popular uprisings were beaten back in Arzens and Pexiora alone. By the summer of 1899, the unrest had spread to the south, with organized labor strikes occuring frequently in Cazalrenoux, Saint-Gaudéric and Tréville-Villespy. Édouard, a hedonist who had never concerned himself with ruling the Empire, responded with cruelty. The Séraphin authorized the Marteaux militias to establish concentration camps for political prisoners, and other citizens guilty of committing treasonous acts. The act proved to be the final straw; with democratic groups organizing under the leadership of Château Floure, the Républicain movement was begun, calling for the Séraphin's overthrow. The Républicains would realize the century-old democratic dream of the Cassonnaise.

The Crowned Sortition and the First Seraphic Republic (1900-1936)

Throughout much of the Dernier Âge, democratic protests were limited to calls for constitutional restraints on the monarchy. With the Républicains now mobilizing militias to oust him from power, Édouard attempted to have the ringleaders arrested and thrown into prison camps. But the military, having endured its own troubles following the war with Aquitayne, refused, and the Séraphin was forced to flee Citadelle Royán for his coastal estate on Île Saint-Étienne in October 1899. Though he was well-protected on the island by loyalist militias and army units, the Seraphic Navy pledged its allegiance to the Républicains and Château Floure. Over the next six and a half months, Île Saint-Étienne was blockaded, preventing the Séraphin from governing. Finally, on May 14th, 1900, facing possible starvation, Édouard yielded to the inevitable and surrendered, abdicating the throne to his fourteen-year old son Alexandre. Alexandre's mother, Séraphin Épouse Vivien had been a secret benefactor of the Républicains, and had fled from Édouard and escaped to the Empire of Nikolia in 1897 with Alexandre's younger sister, Catherine—the future wife of Emperor Petar VII of Nikolia. The young heir was not able to escape with them, and had been kept under virtual house arrest by his father to prevent him from fleeing with them. As a result, when Alexandre was taken into custody on the orders of Château Floure when Édouard surrendered Île Saint-Étienne, he shocked the Républicains and the country at large by condemning his father as a traitor, ordering loyalists to lay down arms, and formally abdicated. Alexandre's speech on May 19th, 1900, the Château Floure Declaration marked the formal dissolution of the Seraphic Empire. That same day the Républicains declared the Empire's new successor-state, the Seraphic Republic.

While preparations for the transition to a democratic form of government had been discussed for years, Château Floure had only begun planning for the scenario since the rise of the Républicain Movement in the summer of 1899. Though Alexandre's declaration had managed to defuse some of the immediate tension, there was still a fear that loyalists would attempt to organize some type of revolt against the new government. To this end, the former Séraphin aided the Républicain cause by formally negotiating foreign powers' diplomatic recognition of the new government. The first head of state to do so was Tiberius Reich of Aquitayne, who officially recognized the Républicain government in June 1900. This recognition was followed shortly thereafter by Milan I of Nikolia, who may have been convinced by Alexandre's mother, Vivien to recognize the new state, weakening the loyalists' position immensely.

In the end, the diplomatic recognition of Aquitayne and Nikolia would prove to be a coup for the young government. Bolstered by international recognition, the delegates of Château Floure had the political leverage necessary to introduce the nation's first constitution, the Accords de Liberté on July 19th, 1900, which authorized the creation of a Sortition Couronné, or Crowned Sortition to replace the defunct monarchy. The new government would be directed largely under the pretenses of a Sortition, with each Préfecture sending representatives selected on merit to attend the national legislature on their behalf. On behalf of his service to new Republic, Alexandre was partially restored as the young Republic's first Proconsul, a hereditary position designed to serve as the 'caretaker' of the new Sortition and serve as the Republic's top ambassador, a post he would successfully represent for fourteen years. The Accords de Liberté were formally submitted to the fifteen individual Préfectures on July 20th, 1900, with ten of the fifteen needed to ratify the constitution and make it law. The tenth Préfecture to ratify it, Cenne-Monestiés did so on February 8th, 1901. Royán Préfecture, the historic seat of the Seraphic Empire, and perhaps the most resistant party overall to change, became the fifteenth and final Préfecture to ratify, choosing symbolically to do so on May 19th, 1901—exactly one year to the day after Alexandre's abdication. By then, the first session of the new national legislature, the Congrès Républicain had already been seated at the new Salle de Congrès building in Citadelle Royán, to forge a continuity of government with the defunct Empire. Despite the abuses endured by the people, and the intense threat of Civil War, not a drop of blood would be spilled in the creation of the new Republic.

François Jaurès of Cahuzac Préfecture was chosen as the new Republican Congress's first Contrôleur, or Controller—the senior-most position of leadership in the Congress, a position that he would be reappointed to three times. The Sortition's political respect and clout grew over time, as it managed to successfully navigate the young Republic's early growing pains. Cassonne's frayed relationships with her neighbors in Astyria slowly healed as the country focused inwardly on balancing its budget and working to industrialize the hitherto-agrarian northern Préfectures. Yet the politics of Astyria were evolving, and the Seraphic Republic's isolation would not last. The regional peace was shattered with the commencement of the Great Astyrian War in 1920. The Republic, like many countries, would join the fight; yet it would emerge from war under duress internally. The years following would prove critical to the Republic.

Libéralisation and the Second Seraphic Republic (1925-1970)

In the consideration of the Seraphic Republic's government history, analysts and historians sometimes bequeath the colloquial sobriquet Second Seraphic Republic to denote the country's system of government after 1936. While in some respects, the Republic has remained the same since its inception, the changes that did occur in 1936 were considered in some circles to be just as revolutionary as the creation of the Republic itself. The eleven-year period of intense internal debate and evolution following the conclusion of the Great Astyrian War would be among the most transformative eras in the history of Cassonne. This era, known as the Libéralisation, or Liberalization, ushered in significant changes to the Seraphic Republic, and forged the democratic institutions which remain in place to this day. Libéralisation emerged in the wake of the Great Astyrian War; a byproduct of the Crise des Classes. As early as 1910, discontent had begun to fester among the Plébéiens, a caste of Seraphic society that was above the abject poverty of the Mendiants, but well below that of the Noblesse and Patriciens, through whom the Sortition was governed and, thus, controlled. As the Republic entered its second decade, some of the old problems related to the original causes of the Républicain movement began to reappear, most notably a growing wealth gap. Petitions for a redress of grievances in the Congrès Républicain failed to reach a successful settlement, though Conseiller (and future Contrôleur) Armand Karoutchi was sympathetic to their plight, confronting the topic by issuing the Été Décret (Summer Decree) in 1715, addressing Congress's need to consider the plight of all Cassonnaise, lest the young Republic be "shackled with a macabre guilt, levied upon the worst of abusers of the dying Empire in the eyes of posterity."

The deterioration of peace in the region would table the issue indefinitely. As the prospects of war increased, the Seraphic Republic began to mobilize its military forces through conscription, which disproportionately affected the Plébéiens. Two distinct draft riots incited by impoverished Cassonnians—one in the ghetto district of Douzens, the other in the northern agrarian village of Les Martys—had to be suppressed by military force, demonstrating the severity of the burgeoning class conflict. During the war, a seditious Private named Richard Cuxac convinced an entire company to walk off the line. After being arrested and tried by court-martial for desertion, the Socialist-oriented Cuxac coined the phrase 'Crise des Classes', meaning a 'Crisis of the Classes', that he felt was inevitable due to the oppression of the wealthy. The fall of Heideland to Communist revolutionaries in 1924 legitimized this warning. After the war's successful conclusion in 1925, a wave of cautious national optimism was undercut by the realization that the fate of Heideland was a threat anywhere inequality was allowed to fester. Though Cuxac was discredited as a traitor in the years following the war, some of his principled arguments were used by the Réformateurs, or Reformers, led by Contrôleur Armand Karoutchi. The successful prosecution of the war, and Karoutchi's exceptional leadership of the Congress therein, had earned him the status of a national hero, lending considerable clout to the cause. Between October 1925 and April 1928, three distinct conventions were held in Citadelle Royán to discuss the inclusion of 'all men of repute' into the national discourse (a fourth meeting in Saint-Catherines in July 1928 was cancelled due to the Seraphic Flu Outbreak of 1928-1929). Women's Suffrage came to the forefront during this period as well.

Riding on a wave of returned economic prosperity after the 1928 Recession, Congress became more inclined to facilitate the needs of the poor into the business of the state. This, coupled with a wave of Progressivism in the wake of the Great Astyrian War, triggered the acceleration of the Libéralisation movement that had begun under Karoutchi. In 1930, the first Convention de Constitutionnel Réforme was organized by the Congress to discuss amendments to the Accords de Liberté. While no consensus was reached at the first convention, a Second Convention in 1931 produced the Traité sur Droits Civils, the Treatise on Civil Rights—a series of amendments designed to protect the rights of citizens irrespective of their class. This included the right to peacefully assemble, the freedom to petition the government for a redress of grievances, and most notably, the right of women to participate in the Cassonnaise Sortition. The most pronounced change in Cassonne, and by far the biggest victory for the Plébéiens, came at the Third Convention in 1935. Two matters in particular which had long-loomed over the national discourse—universal suffrage in the Sortition, and the desire for a popularly-elected head of government—were at the forefront in 1935. Thanks to the efforts of prominent reform voices like Louis Noiret and Gaspard Piccoli, the Convention rescinded the requirement of land ownership for participation in the Sortition, instead requiring only one to have completed their national term of military service.

Séparation Politique and the Modern Seraphic Republic (1970-Present)

Though Libéralisation was largely concluded with the Third Convention in 1935 and the changes effected in 1936, the politics of Libéralisation persisted well into the 1960s. Certain political stability coincided with a period of economic prosperity known as the Ère de Bienveillance, or Era of Benevolence. Median incomes for the poorest thirty percent of Cassonnians rose every year between 1939 and 1959, then again from 1962 to 1969. By the end of the 1960s, the national average life expectancy, literacy rate and income per capita were at their highest-ever levels; meanwhile, the poverty rate in 1969 fell below 3.5% for the first—and last—time in the history of the Republic. This robust social age was among the greatest in Cassonne's history, a 'second Grand Âge' that would drive the Seraphic Republic forward into the new millennium as a preeminent Astyrian power.

By 1970, however, the Chancellor Alexandre had developed lung cancer. As his condition worsened, a public vigil was held in his honor, demonstrative of the country's affection towards him. Alexandre died on March 11th, 1970, at the age of 48; his son, Marquise Colau assumed the position as interim Head of State. Yet Marquise would not retain the title for long: less than a month after ascending to the rank, Marquise left the office and called for elections. The city-state of Valle Crucis, to which the Seraphic Republic had been formally allied with since 1901, threatened in April 1970 to freeze the assets of the Democratic People's Republic of Heideland it held in Valle Crucian banks, following reports of widespread human rights abuses and a famine resulting from government mismanagement and corruption. The Heider government responded after months of failed negotiations by sponsoring a series of terrorist attacks in Valle Crucis, including a car bombing at the Port of Valle Crucis, killing 271 people—including 12 Cassonnians. The Seraphic Republic threatened military intervention against Heideland, leading the Communists to counter by mobilizing their nuclear rocket corps, threatening to enact a 'launch-on-warning' policy should the Seraphic Republic risk an invasion.

The three-week long 1970 Heider Missile Crisis reached a peaceful, albeit scandalous end in May 1970, when both sides agreed to international mediation from the Evenguard of Azura. The relief over the easing of tensions was irreparably smashed when the Montréat Gazette revealed that Conseiller Catherine Baer, at the urging of the Congressional leadership, had secretly arranged for the payment of a series of bribes, both to the Valle Crucian banks to release Heider assets, and to the Heider Government to expedite a quick-conclusion to the standoff. The scandal, known as the Affaire Honteuse (Shameful Affair) severely crippled the Republic's prestige around the region, and led Valle Crucis to suspend diplomatic ties with Cassonne. Coupled with the severe economic recession which followed the conclusion to the Missile Crisis, Cassonne withdrew from all of its international commitments. The government retreated into a policy of Séparation Politique, or Political Separation, having not only suffered the sting of an international scandal, but also having pushed itself to the brink of nuclear war. Hit with the trifecta of the so-called Mega-Recession which would linger throughout the next decade, Cassonnaise will to intervene in foreign affairs was wholly sapped. A rash of resignations in Congress completed the so-called Année de l'Enfer (Year of Hell), sending the Seraphic Republic down a path on which it remains on to the present day. While certain economic reforms enacted in the 1980s and 1990s—including a push to increase international trade after a twenty-year slump—helped finally spur a financial recovery in the mid-'90s, the country remains locked into a condition of armed neutrality.