Coian Evacuation: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (5 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

Etruria’s imperial history with Satria began in the late 16th century with the establishment of “Povelian Quarters” across several port cities for access to spices, textiles and resources. These Quarters would constitute the foundation of later direct intervention by the [[United Kingdom of Etruria]] beginning in the 1820s. In [[Zorasan]] and [[Rahelia]], colonial endevours were driven primarily by repeated conflicts with the [[Gorsanid Empire]]. Throughout the 1820s and 1830s, the focus was on establishing greater influence in Satria, with repeated localised conflicts and shifting alliances led by the [[Grand Satrian Company]], culminating in the outright annexation of its Satrian possessions in 1849, this was followed in 1860 with the [[Etrurian conquest of Zorasan]]. | Etruria’s imperial history with Satria began in the late 16th century with the establishment of “Povelian Quarters” across several port cities for access to spices, textiles and resources. These Quarters would constitute the foundation of later direct intervention by the [[United Kingdom of Etruria]] beginning in the 1820s. In [[Zorasan]] and [[Rahelia]], colonial endevours were driven primarily by repeated conflicts with the [[Gorsanid Empire]]. Throughout the 1820s and 1830s, the focus was on establishing greater influence in Satria, with repeated localised conflicts and shifting alliances led by the [[Grand Satrian Company]], culminating in the outright annexation of its Satrian possessions in 1849, this was followed in 1860 with the [[Etrurian conquest of Zorasan]]. | ||

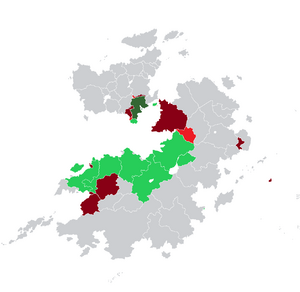

[[File:GreatBetrayal.png|300px|thumb|Etrurian war aims during the Great War and their result: {{color box|#346733|Etruria}}<br/>{{color box|#27cd59|Etrurian colonies}}<br/>{{color box|#ed1c24|Claimed territories transferred to Etruria}}<br/>{{color box|#880015|Claimed territories denied to Etruria}}]] | |||

In 1888, the [[San Sepulchro Revolution]] and establishment of the [[Etrurian Second Republic]] would result in a considerable overhaul of Etruria’s colonial possessions, resulting in the establishment of [[Etrurian Satria]], [[Free Satria]], [[Balesaria]], [[Cyracana]], [[Etrurian Rahelia]] and the two protectorates of [[Ninavina]] and the [[Sublime State of Pardaran]]. From 1888 until 1920, Etruria was averse to implementing a “settler colonialism”, instead focusing on operated relatively de-centralised colonial administrations that mostly managed resource extraction, regulated internal and external trade and security affairs. This changed in wake of the [[Great War (Kylaris)|Great War]] and the establishment of the [[Greater Solarian Republic]]. Between 1938 and 1943, an estimated 243,000 Etrurians settled across its Coian colonies. However, the GSR retained and continued the effort of “indigenising” colonial authorities as part of the [[Paxean Republic]] theory and establishing a {{wp|Pluricontinentalism|pluricontinental state}}. This led to the establishment of a transnational colonial elite, who found little support or legitimacy among their native peoples. This coincided with the decades-long effort and policy of industrialising Etruria's "fourth shore" and integrating the economies of its Coian colonies through the [[Via Imperia]] highway, which was constructed between 1910 and 1942, linking XX (modern day [[Patasura]]) with [[Sadah]] (modern day [[Irvadistan]], [[Zorasan]]). | |||

The direct origins of Operation Mercury lay with Etrurian war aims during the [[Great War (Kylaris)|Great War]]. Throughout the imperial era, Etruria's principal rivals in northern Coius were [[Estmere]] in Satria, and [[Gaullica]] in [[Rahelia]]. Etruria's belated entry to the war, was due to its lengthy negotiations with [[Estmere]] and [[Werania]], in which it laid claim to [[Tsabara]], modern day [[Ajahadya]] and [[Ansan]], as well as territories in Euclea. Despite playing a pivotal role in the Coian theatre, Etruria saw many of its claims denied during peace negotiations, leading to the [[Great Betrayal]] myth propagated by ultranationalist circles. Etruria's territorial gains post-war, ostensibly led to a nationalist revolt against the Second Republic during the [[Legionary Reaction]], which resulted in the establishment of a far-right regime known as the [[Greater Solarian Republic]]. The GSR upon its founding, began preparing Etruria for renewed conflict in the hope of "redeeming Etruria" and "course correcting its imperial destiny", through the conquest of its Great War-era claims. Despite being denied the opportunity to annex [[Ajahadya]] into Etruria's empire, it was instead granted a period of occupation, similar to the [[Etrurian Occupation Zone in Amathia]]. In 1942, the GSR annexed both into the Etrurian empire, in contravention of the Great War peace-settlement. | |||

In 1943, the [[Solarian War]] began with the [[Etrurian invasion of Piraea|invasion of Piraea]], which was followed by a declaration of war upon the GSR by the [[Community of Nations]]. The inclusion of [[Estmere]] within this coalition enabled the GSR the justification to invade [[Tsabara]] and [[Padartha]], making rapid gains in the former, but slower gains in the latter. With the majority of Etruria's war effort being focused on Euclea, third parties such as the [[Green Bashurat Movement]] in modern [[Ajahadya]] and the [[Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command]] in modern day [[Zorasan]] seized the opportunity to attempt national liberation campaigns. Localised uprisings also took place within [[Etrurian Satria]], [[Etrurian Rahelia]], [[Cyracana]] and revolts against its protectorates in [[Pardaran]] and [[Ninavina]]. The greatest uprising took place in modern-day [[Ajahadya]], which rapidly destabilised Etrurian control and forced a retreat by Etrurian forces in mid-1945. The year of 1945, would mark the steady decline of Etruria's fortunes in Coius; CN Forces successfully landed in [[Manara]], northern Tsabara, while Estmerish, Senrian and Soravian forces successfully broke Etrurian forces in the [[Battle for Patasura]]. Though its lines began to collapse in Coius, the Comando Supremo felt confident it could establish a fortifiable position centred around Cyracana, Pardaran and western Khazestan, however, the [[Soravia|Soravian offensive]] in [[Amathia]] broke the Etrurian [[Praetoriano Line]] and threatened to see Soravian forces advance on western Etruria, this provoked sufficient fear for the homeland's defence that the Comando Supremo authorised plans to begin evacuating Etrurian forces and settlers from Coius to then be deployed in defence of Etruria proper. | |||

=== Planning === | |||

Planning for an evacuation of Coius began in August 1945 at the behest of the [[Supreme Command of the Republic|Comando Supremo]], responsibility was delegated to [[Giorgio Urbano Ademollo]], the Minister for Ordinance and Industry, [[Sotiriano Gennaro Vinci]], the Minister for the Navy and [[Aurelio Alessandro Cannavale]], the Minister for the Merchant Fleet. The trio with the assistance of army and navy officers, as well as civil servants initially opted for an immediate operation, proposing the immediate dispatch of communications to colonies ordering them to begin transporting Etrurian civilians to [[Bhalsera|Balesaria]] (modern day [[Rajyaghar]]). This would then be followed by a hopefully organised and steady withdrawl of military forces to Etruria from several locations. However, this was plan was rejected by the Comando Supremo, who wished for the evacuation of machinery, resources and an operation that would not require such an intense logistical chain. | |||

In early September, the group reconvened and instead work on a "staged and methodical withdrawal" that conversely, would be dependent on a longer-term defence by Etrurian forces. The new plan also included more than one port to reduce the logistical strain and time consumption. The group identified and selected [[Balesaria]] ([[Bhalesrah]]), [[Chaboksar]], [[Bandar-e Sattari|Virgilia]] ([[Bandar-e Sattari]]) and [[At-Turbah|Porto di Scippio]] ([[At-Turbah]]). These were the deepest ports of the empire on the Acheolian coast of Coius and were the most developed, guaranteeing a high density of those civilians needing evacuation. The group planned the operation to take place over the course of four months; four weeks for evacuating factories and resources, six weeks to evacuate civilians and wounded servicemen and seven weeks to evacuate military forces and equipment. The group ordered Aurelio Alessandro Cannavale and a smaller committee of civil servants to identify the civilian and military vessels needed for the operation. Over the course of several weeks, the Cannavale Group comandeered up to 200 vessels, ranging from ocean going liners, tankers, freighters to National Republican Navy warships. Admiral Vinci was forced to retask the Solarian and the Acheolian Fleets to maintain combat patrols at the Aurean Straits and eastern Acheolian Sea respectively, as well as conduct escort duty for the convoys traversing back forth between Coius and Etruria - this would place great strain upon the Etrurian Navy and would lead to serious loss of life in several incidents during the operation. | |||

The plan also resulted in the reorganising of [[Centuripe]], [[Accadia]], [[Porto di Sotirio]] and [[Solaria]] into being the receiving ports, this would place considerable strain on the outgoing supply of Etrurian forces deployed in Coius. This in turn degraded the defensive lines the operation dependened upon, leading to chaotic scenes in the final stages of the evacuation. | |||

Solarian War historian, Stefano Riolo remarked, "Operation Mercury was ironically, the best operation planned and executed by the GSR during the entire conflict, in contrast to virtually every military operation, but it was also the one that stretched the maritime services and capabilities to their absolute limits. Ostensibly, it would prove to be an operation well planned but beyond the limits of a besieged nation, which in turn would lead to serious excesses and decisions beyond the pale." | |||

== Operation Mercury == | == Operation Mercury == | ||

| Line 73: | Line 85: | ||

== Controversies == | == Controversies == | ||

==== Sinking of SS Marco Loredan ==== | ==== Sinking of SS Marco Loredan ==== | ||

==== Liquidation Process ==== | |||

==== Massacres of Etrurian settlers ==== | ==== Massacres of Etrurian settlers ==== | ||

==== Reprisals against collaborators ==== | ==== Reprisals against collaborators ==== | ||

Latest revision as of 13:11, 11 December 2022

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

| Coian Evacuation Operation Mercury | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Solarian War | |||||||

Chaboksar during the evacuation of Etrurian civilians and soldiers in early 1946. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Etrurian Dominions and Protectorates |

Community of Nations Forces Template:Country data Estmere Other forces | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

22,430 killed 39,600 injured 18,992 captured | |||||||

|

10,340 Etrurian civilians killed 13,489 Satrian and Zorasani civilians killed | |||||||

The Coian Evacuation (Vespasian: Evacuazione Coiana), also known as Operation Mercury (Operazione Mercurio), was the evacuation of more than 500,000 Etrurian soldiers, civilians and colonial elites in Coius during the latter stages of the Solarian War, from various beaches and harbours across Etrurian Satria, Etrurian Rahelia and the Sublime State of Pardaran. The operation took place between 2 November 1945 and 5 February 1946 and commenced following the Battle for Patasura and the breakthrough of Soravian forces in Amathia. Fearful of losing vast quantities of manpower to the Community of Nations Forces in Coius, the Greater Solarian Republic leadership ordered a mandatory evacuation of all Etrurian nationals and colonial elites from its colonies, followed by military forces. The evacuation saw the complete abandonment of territories, alongside economic assets, documents and the entire political leadership, resulting the collapse of law and order in Etruria's erstwhile colonies, enabling the emergence of new nations from its colonial empire.

The Solarian War begain 1943, with the Etrurian invasion of Piraea, though part of its wider wargoals was the annexation of former Gaullican colonies that Etruria claimed but was denied in wake of the Great War. Owing to Estmere being granted mandatory control over Gaullica's possessions, Etruria invaded Padartha from Etrurian Satria, expanding the conflict to Satria, this coincided with an invasion of southern Tsabara from Etrurian Rahelia. However, the Solarian War swiftly resulted in the Community of Nations establishing a unified command, resulting in the entry of Senria, Soravia and several Asterian powers. Notably, Ajahadya backed by Shangea also intervened against the Greater Solarian Republic, greatly worsening the balance of forces in Satria. Despite initial success in Padartha and Ajahadya, Etrurian forces were stalled throughout 1944 in Satria, while its greater gains in Tsabara were reversed with the Estmerish-Rizealander amphibious landing at Manara and the rapid collapse of Etrurian forces in Tsabara. Throughout much of 1945, Etrurian forces were struggling to maintain defensive positions in Satria and Rahelia, and in the summer, GSR regime agreed on plans to possibly evacuate Coius and abandon its posessions there. This situation was forced with the successful Soravian offensive in Amathia, which broke through Etrurian lines and came to threaten Etruria proper. In October 1945, the GSR Supreme Command (Comando Supremo) authorised plans to evacuate Coius for the defence of Etruria itself.

Under Operation Mercury, four Coian harbours were selected, Belisaria (Bhalesrah), Chaboksar, Virgilia (Bandar-e Sattari) and Porto di Scippio (At-Turbah), these ports were the largest and deepest within the Etrurian Colonial Empire and all were located on the Acheolian coast and all were linked by the Via Imperia highway. Beginning on November 2 1945, the first four weeks were dedicated to extracting and transporting factory machinery, resources and financial assets (including gold bullion and jewels stolen from local Satrian elites during the Etrurian Second Republic). Beginning in late December, the operation began to evacuate Etrurian civilians, auxiliaries and select Satrian and Zorasani elites who served in the colonial administrations. By January, Belisaria had fallen to Estmerish forces and Porto di Scippio faces the threat of Rizealander forces, ending operations in those two locations. By this time, it was becoming known among colonial peoples that the Etrurians were fleeing and chaos began to spread in Virgilia and Chaboksar. This had a detrimental effect on the evacuation of Etrurian soldiers and their equipment, though a majority were successfully withdrawn.

In total 503,602 people were evacuated, including 320,155 soldiers, 156,862 Etrurian civilians and 26,585 Satrians and Zorasanis. However, an estimated 41,422 Etrurian soldiers were killed or captured during the operation, while 10,340 Etrurian civilians were killed, over 8,000 of whom died aborad the SS Marco Loredan, a cruise liner which was sunk by a Soravian submarine. A further 2,000 were killed in a series of massacres in southern Patasura and Khazestan. The extraction of entire factories and financial assests has been described as one of the "largest state-backed thefts" in history, while the legacy of how Satrians and Zorasanis were evacuated remains a controversial legacy. The greatest impact of Operation Mercury was from the rapid abandonment of colonial possessions, leaving tens of millions of Satrians, Pardarians and Rahelians without any organised governance, the evacuation also led to the emergence of fledgling national movements that go onto form Patasura, Rajyaghar, the Kingdom of Khazestan, Emirate of Irvadistan, Confederation of Riyadha and the Kexri Republic, as well as spark civil war in Pardaran. The operation also marked the collapse of one of the largest empires in history and the demise of Etruria as a great power, as part of the wider collapse concluding the Solarian War.

Background

Etruria’s imperial history with Satria began in the late 16th century with the establishment of “Povelian Quarters” across several port cities for access to spices, textiles and resources. These Quarters would constitute the foundation of later direct intervention by the United Kingdom of Etruria beginning in the 1820s. In Zorasan and Rahelia, colonial endevours were driven primarily by repeated conflicts with the Gorsanid Empire. Throughout the 1820s and 1830s, the focus was on establishing greater influence in Satria, with repeated localised conflicts and shifting alliances led by the Grand Satrian Company, culminating in the outright annexation of its Satrian possessions in 1849, this was followed in 1860 with the Etrurian conquest of Zorasan.

In 1888, the San Sepulchro Revolution and establishment of the Etrurian Second Republic would result in a considerable overhaul of Etruria’s colonial possessions, resulting in the establishment of Etrurian Satria, Free Satria, Balesaria, Cyracana, Etrurian Rahelia and the two protectorates of Ninavina and the Sublime State of Pardaran. From 1888 until 1920, Etruria was averse to implementing a “settler colonialism”, instead focusing on operated relatively de-centralised colonial administrations that mostly managed resource extraction, regulated internal and external trade and security affairs. This changed in wake of the Great War and the establishment of the Greater Solarian Republic. Between 1938 and 1943, an estimated 243,000 Etrurians settled across its Coian colonies. However, the GSR retained and continued the effort of “indigenising” colonial authorities as part of the Paxean Republic theory and establishing a pluricontinental state. This led to the establishment of a transnational colonial elite, who found little support or legitimacy among their native peoples. This coincided with the decades-long effort and policy of industrialising Etruria's "fourth shore" and integrating the economies of its Coian colonies through the Via Imperia highway, which was constructed between 1910 and 1942, linking XX (modern day Patasura) with Sadah (modern day Irvadistan, Zorasan).

The direct origins of Operation Mercury lay with Etrurian war aims during the Great War. Throughout the imperial era, Etruria's principal rivals in northern Coius were Estmere in Satria, and Gaullica in Rahelia. Etruria's belated entry to the war, was due to its lengthy negotiations with Estmere and Werania, in which it laid claim to Tsabara, modern day Ajahadya and Ansan, as well as territories in Euclea. Despite playing a pivotal role in the Coian theatre, Etruria saw many of its claims denied during peace negotiations, leading to the Great Betrayal myth propagated by ultranationalist circles. Etruria's territorial gains post-war, ostensibly led to a nationalist revolt against the Second Republic during the Legionary Reaction, which resulted in the establishment of a far-right regime known as the Greater Solarian Republic. The GSR upon its founding, began preparing Etruria for renewed conflict in the hope of "redeeming Etruria" and "course correcting its imperial destiny", through the conquest of its Great War-era claims. Despite being denied the opportunity to annex Ajahadya into Etruria's empire, it was instead granted a period of occupation, similar to the Etrurian Occupation Zone in Amathia. In 1942, the GSR annexed both into the Etrurian empire, in contravention of the Great War peace-settlement.

In 1943, the Solarian War began with the invasion of Piraea, which was followed by a declaration of war upon the GSR by the Community of Nations. The inclusion of Estmere within this coalition enabled the GSR the justification to invade Tsabara and Padartha, making rapid gains in the former, but slower gains in the latter. With the majority of Etruria's war effort being focused on Euclea, third parties such as the Green Bashurat Movement in modern Ajahadya and the Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command in modern day Zorasan seized the opportunity to attempt national liberation campaigns. Localised uprisings also took place within Etrurian Satria, Etrurian Rahelia, Cyracana and revolts against its protectorates in Pardaran and Ninavina. The greatest uprising took place in modern-day Ajahadya, which rapidly destabilised Etrurian control and forced a retreat by Etrurian forces in mid-1945. The year of 1945, would mark the steady decline of Etruria's fortunes in Coius; CN Forces successfully landed in Manara, northern Tsabara, while Estmerish, Senrian and Soravian forces successfully broke Etrurian forces in the Battle for Patasura. Though its lines began to collapse in Coius, the Comando Supremo felt confident it could establish a fortifiable position centred around Cyracana, Pardaran and western Khazestan, however, the Soravian offensive in Amathia broke the Etrurian Praetoriano Line and threatened to see Soravian forces advance on western Etruria, this provoked sufficient fear for the homeland's defence that the Comando Supremo authorised plans to begin evacuating Etrurian forces and settlers from Coius to then be deployed in defence of Etruria proper.

Planning

Planning for an evacuation of Coius began in August 1945 at the behest of the Comando Supremo, responsibility was delegated to Giorgio Urbano Ademollo, the Minister for Ordinance and Industry, Sotiriano Gennaro Vinci, the Minister for the Navy and Aurelio Alessandro Cannavale, the Minister for the Merchant Fleet. The trio with the assistance of army and navy officers, as well as civil servants initially opted for an immediate operation, proposing the immediate dispatch of communications to colonies ordering them to begin transporting Etrurian civilians to Balesaria (modern day Rajyaghar). This would then be followed by a hopefully organised and steady withdrawl of military forces to Etruria from several locations. However, this was plan was rejected by the Comando Supremo, who wished for the evacuation of machinery, resources and an operation that would not require such an intense logistical chain.

In early September, the group reconvened and instead work on a "staged and methodical withdrawal" that conversely, would be dependent on a longer-term defence by Etrurian forces. The new plan also included more than one port to reduce the logistical strain and time consumption. The group identified and selected Balesaria (Bhalesrah), Chaboksar, Virgilia (Bandar-e Sattari) and Porto di Scippio (At-Turbah). These were the deepest ports of the empire on the Acheolian coast of Coius and were the most developed, guaranteeing a high density of those civilians needing evacuation. The group planned the operation to take place over the course of four months; four weeks for evacuating factories and resources, six weeks to evacuate civilians and wounded servicemen and seven weeks to evacuate military forces and equipment. The group ordered Aurelio Alessandro Cannavale and a smaller committee of civil servants to identify the civilian and military vessels needed for the operation. Over the course of several weeks, the Cannavale Group comandeered up to 200 vessels, ranging from ocean going liners, tankers, freighters to National Republican Navy warships. Admiral Vinci was forced to retask the Solarian and the Acheolian Fleets to maintain combat patrols at the Aurean Straits and eastern Acheolian Sea respectively, as well as conduct escort duty for the convoys traversing back forth between Coius and Etruria - this would place great strain upon the Etrurian Navy and would lead to serious loss of life in several incidents during the operation.

The plan also resulted in the reorganising of Centuripe, Accadia, Porto di Sotirio and Solaria into being the receiving ports, this would place considerable strain on the outgoing supply of Etrurian forces deployed in Coius. This in turn degraded the defensive lines the operation dependened upon, leading to chaotic scenes in the final stages of the evacuation.

Solarian War historian, Stefano Riolo remarked, "Operation Mercury was ironically, the best operation planned and executed by the GSR during the entire conflict, in contrast to virtually every military operation, but it was also the one that stretched the maritime services and capabilities to their absolute limits. Ostensibly, it would prove to be an operation well planned but beyond the limits of a besieged nation, which in turn would lead to serious excesses and decisions beyond the pale."