Themiclesia

Themiclesia | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

| Anthem: Air of Curvilinear Clouds (慶雲歌) Royal anthem: Air of Mosses (南山有臺) | |

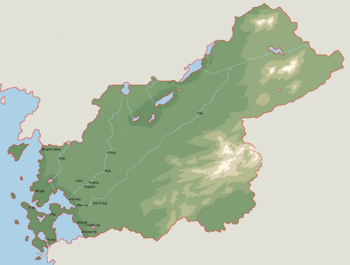

Map of continental Themiclesia | |

| Capital | Kien-k'ang |

| Official languages | Shinasthana |

| Recognised regional languages | Dayashinese Menghean language Hallian |

| Demonym(s) | Themiclesian |

| Government | Constitutional monarchy |

• Emperor | Current emperor |

• Prime Minister | Lja Le |

| Establishment | |

| 256 | |

• Current dynasty | 1558 |

| Area | |

• | 2,899,659.06 km2 (1,119,564.62 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 4% |

| Population | |

• 2019 estimate | 40.4 million |

• 2014 census | 39.2 million |

• Density | 10/km2 (25.9/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2017 estimate |

• Total | $1,791,000,000,000 (22) |

• Per capita | $44,340 (10) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2015 estimate |

• Total | $2,081,000,000,000 (11) |

• Per capita | $51,503 (2) |

| Gini (2015) | 25.7 low |

| HDI (2015) | 0.93 very high |

| Currency | Auric catty (鎰, ′jik) (€) |

| Time zone | UTC+4 – +6 (West, East, Remote East) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+1 |

| Yes | |

| Date format | mm-dd-yyyy (Gregorian) yy-cc-mm (official) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +2 |

| Internet TLD | .tm |

Themiclesia is a parliamentary democracy and constitutional monarchy situated on the east side of the Halu'an Sea. It borders Nukkumaa to the north, Polvokia to the northeast, Dzhungestan to the east, and Maverica to the south. It is typically received as stable, well-off, mid-sized country in Septentrion, rich in history and culture, which links it primarily to Menghe, though elements of other cultures are also represented. Themiclesia is internationally noted for its technological advancement and moderate foreign policy, though it is an active member state in multiple international organizations.

Name

There is no formal legislation stating what Themiclesia's name is in Shinasthana, the lingua franca of the country. The name tjerh-tanh (震旦) frequently is used in ordinary conversation, but the word "state" (邦, prong) is the typical term in legislation. In formal treaties, the name of Themiclesia appears as Tsjinh, the Patriarchs, and Barons and Manor-holders and Missions, and Houses, and Lords (晉邦伯眔侯甸任眔百姓眔君, tsjinh-prong-prak-n.rep-go-linh-njem-n.rep-prêk-sjêngh-kjur). During the 19th century, the term Shinasthana and the Barons and People thereof was sometimes used as well.

The country's official Anglian name, "Themiclesia" is far removed from its etymological origin. Much of modern Themiclesia was under the rule of the Tsjinh in the 300s, when Mavericans started to use Shinasthana as a portmanteau of Tsjinh + -sthana (locative suffix); more than a thousand years later, Shinasthana was borrowed into Hallian as Thimestheni, when either clerical error or arbitrary phonetic Sylvanization, or both, resulted in its surfacing as Themiclesia in central Casaterra. As eastern and northern Casaterran nations were not influenced by this change, their names for Themiclesia remain Thimestheni.

Meng Themiclesians originally had no name for their ethnic or cultural group; to denote all the Meng polities in Themiclesia, the word r′jêt-prong (徹邦) or "all the states" was used, since the word "state" implied a form of political organization peculiar to Meng settlers. Since the Mrangh, the Meng names trjung-prong (中邦) and mg′ra′ (夏), meaning "middle state" and "rightful, legitimate" respectively, came into general use. On the other hand, the exonym Shinasthana was reborrowed as tjerh-tanh (震旦), two characters simulating the Maverican pronunciation but meaningless. This name was favoured in geographic and diplomatic contexts, while those stipulating political legitimacy were used in political contexts.

By the 14th century, tjerh-tanh had overtaken the use of trjung-prong as a political name for Themiclesia, whose government gradually became less entrenched in the doctrine of Menghean imperial legacy. Part of this detachment came from growing hostility between the Yi dynasty of Menghe and Themiclesia in that century and the subsequent fact that Themiclesia became a vassal to Menghe in 1385.

History

Themiclesia possesses a tradition of written history starting from the 4th century, but prior to this time historical events are only recorded as annals or passing references. Traditionally, history is almost exclusively focused on the post-settlement part of history and the history of Menghe (which Themiclesia identified with), but a growing portion of studies incorporate give consideration to prehistoric societies that inhabited the country prior to Menghean presence.

Protohistoric period

Evidence of human habitation in Themiclesia dates to the 3rd millennium BCE, and extraction of turquoise and lapis lazuli is closely associated with the earliest people in Themiclesia. As there is no remnant of agricultural activity, it is often assumed that these people were nomadic. The cultural affinity of these groups remain uncertain. A Proto-Chikai tablet of the mid-2nd millennium BCE, unearthed in northwestern Menghe, identifies a certain westerly "place where sky meets earth" as the place where "sky-blue stones" and "deep-blue stones" are bought, implying that turquoise and lapis lazuli were by then consistently mined and can be bought from individuals who extract them.

For centuries, the Proto-Chikai and then the Achahan cultures controlled the Lapis Road, the trade route linking the Achahan heartland to Themiclesia, over Dzhungestan. The most notable commodity traded over the road was lapis lazuli, highly prized in Achahan and Meng cultures for its vibrant blue colour and association with the mythologized sky. The stones were applied not only in ritualistic contexts but also secular artwork that flourished in Menghe under the Gojun and Jun dynasties. The Achahan culture mysteriously disappeared in the 10th century, leading to a sudden shortage of the minerals in Menghe; this shortage is thought to have motivated Menghean kings to seek to recover its supply by re-opening the trade route.

Dark Ages

The majority of Themiclesian people are part of the Meng ethnic group, which inhabited and gives its name to Menghe. As a broadly-accepted date, Meng people first arrived in Themiclesia between 900 and 800 BCE. In Menghean historical canon, this movement was attributed to Meng kings' desire to establish control over the Themiclesia's lapis lazuli and turquoise veins, but some historians argue that the trade route was never fully abandoned, and populations have moved over it continuously, even if not travelling its full length.

It is not clear when the earliest Meng settlements actually appeared, though their development was undoubtedly slow, given the sparseness of material remains. Fringe scholars have argued that initial Meng settlements date to the 11th century, though their views have met little support from other scholars. The earliest remains that firmly demonstrate Meng affinity is a dagger-axe that dates to the 10th century, but it is an import from Menghe. Evidence for bronzeworking with the piece-mould casting method, a technique associated with Meng bronze working, appears in the 9th century. Mainstream historians ascribe a plausible date of Meng settlement in the 8th century. At this time, bronze artifacts are associated with inhabitation and agriculture, and most of them are cast from local bronze, implying a stable source of bronze has been found in Themiclesia.

The period following initial Meng settlement is conventionally called the Themiclesian Dark Ages, as no historical writing credibly describes this period and no meaningful written material has been archaeologically recovered. The earliest written words are ostraca or tablets that bear a single Mengja character, probably functioning as labels. The earliest bronze inscriptions date to the 7th century but bear only names. Though tortoise-shell divination was also practiced in Themiclesia, inscriptions appear in the 5th century BCE. This remarkable want of writing has once been interpreted as the absence of the same processes that give rise inscribed bronze vessels and tortoise shells in Menghe, but some scholars believe that is to mistake the phenomenon as the cause.

Recent archaeology has brought new light to study of the Dark Ages that once relied heavily on mythology and references in Menghean texts that may be more rumour than account. According to Nathan B., "the first walled settlements appeared during the so-called Dark Ages and with it probably the centres of authority that command the labour to erect them." In the 6th through 4th centuries, settlements expanded and showed divisions into commercial, craft, and residential districts. These facts are plausibly connected with revolutions in the economic relationships between city and rural areas. This development must be reckoned together with the emergence of writing in the next century. In this view, the Dark Ages were far from the "brutish time before civilization" but "the time when cities and states were born".

A recent study on Dark Ages history in Themiclesia makes the conclusion that "family trees and cultic activities, far from static facts of antiquarian interest, are the cornerstone of Themiclesian society and politics in the dark ages". The study found a high degree of similarity between individual names, clan names, and place names; that is to say, the same name can represent a person, his clan, or the place where his clan lives. It argues that "to understand family trees and sacrifices is to rediscover forgotten histories prior to the rise of geographic politics and spacial states" and "maps that purport borders and centres of power cannot be accurate because politics often occurred irrespective of geography."

Archaic Period (385 BCE – 315 CE)

The Archaic Period is the general name for the 700 years between 385 BCE to 315 CE when writing was practiced in Themiclesia but not in sufficient quantities or contexts to permit a very comprehensive study of the period at depth. For chronological reasons, the first 600 years are divided into 3 periods, named the Early, Middle, and Late Archaic, and the remaining 100 years is usually considered as a separate Transitional Period, heralding the arrival of the Classical Period when literature experienced an explosive growth and thereby allowed a completely different level of study.

The 700-year Archaic Period was once held as a largely static, unchanging era with few remarkable or worthwhile events, and the subsequent explosion in literature and political dynamic in the Classical Period was esteemed as revolutions in society and statecraft. But since the 1940s, there has been a change in the majority view, now describing the Archaic Period as a dynamic period in its own right and only appearing static under the genre of historical material. On the one hand, important changes must be assigned to this epoch if conventional retrojections of the Classical Period into the Dark Ages are to be abandoned. On the other hand, the increasing abundance of archaeological information has expanded historians' horizon into this period.

The earliest Meng settlers lived in clans-like settlements of around 100 – 500 people and usually left only oracular records of their cultic activities, from which only quotidian events and genealogies could be reconstructed around the turn of the 4th century BCE. Thence emerges a picture of dozens of settlements engaged through marriage, diplomacy, and warfare. Some describe these settlements as primitive city-states and analogize them to those in Classical Kyraia, noting the use of clans as sub-units of the state. But it is the majority contention that this over-appriases the sophistication of most settlements in the Early Archaic. The period is principally known from Springs and Autumns of Six States (六邦春秋, ruk-prang-ktur-skwe), dating to the 390s, transducing extant oracular records into writing.

The Early Archaic conventionally from around 385 to 250 BCE, is archaeologically difficult to tell apart from the last phase of the Dark Ages; there were no significant breaks in the transition from the Dark Ages to the Early Archaic anywhere in Themiclesia. This means that the records available from the Early Archaic may well be reflective of the latter part of the Dark Ages as well.

Around the start of the Middle Archaic in 250 BCE, many settlements simultaneously showed signs of rapid growth for a reason not yet understood. New quarters were established around existing ones, and in them, more types of houses as well as separate areas for communal religious precincts not clearly connected to any one household. The burial record shows an "explosive increase" in quantity and quality of grave goods around the same time. This increase in wealth is such that a rich burial in 450 BCE is hardly distinguishable from a middling one around 150 BCE.

The practice of human sacrifice, once a rarity, became routine in large burials; the largest are commonly interred with 50 – 150 victims. In terms of other grave goods, the quantity of bronze buried with the principal deceased has been used as a metric to illustrate the explosive wealth of the Middle Archaic Period. A grave with 50 kg of bronzes would be considered exceptionally rich only 3 centuries ago, but over 47 graves with more than 1,000 kg of bronzes have been discovered in this period and at several sites.

The oracular text as transduced has also been demonstrated to document this phenomenon: sacrifices to ancestors in the Early Archaic are rarely accompanied by the quantities of victims but are routinely thus in the Middle to Late Archaic. This mehses with the archaeological conclusion that most sacrifices in the Dark Ages and Early Archaic were small in scale, with fish being the most common offering and later consumed; later, offerings could encompass dozens or even hundreds of humans and cattle, and these were not consumed but completely given to the divinities.

The exceptional growth in wealth in the Middle Archaic Period has been subject to much speculation, some holding that an emerging notion of kingship was responsible. Those rich burials would, under this paradigm, belong to quasi-kings who were not only paterfamilias but also became high priest and warlord at the same time, thus granting them effectively the right to possess their settlements as chattels. If this development of kingship was the genuine reason behind the phenomena observed, it would have developed very rapidly and absolutely, with relatively little time for authority to develop, noting that the aggregation of royal authority was usually a gradual process in other societies. In response, such authorities usually appeal to external influence at work, even though no dynasties were overthrown.

The Late Archaic Period (1 – 215 CE) is also known as the Heroic Age owing to the summary comparison made by Lord Brem to Kyraian legend in the 1800s. Contemporary records are still poor in this period, but more narratives pertaining to individual rulers who are dateable to this period exist. Many of these are associated with individual states from later times.

The Late Archaic, archaeologically, is a transformative period with the widespread adoption of iron in tools and weapons. Iron-smelting technology appears to have originated in Maverica and spread from the south to the north. The impact of iron agricultural tools was immeasurable as iron was much more available than bronze and permitted many more fields to be opened. Thus, not only was there an increase in wealth during the Late Archaic but also a general increase in wealth.

Civil strife appears to have been more common in the Late Archaic than in preceding periods. On the one hand, the increasing size of settlements the extent that some might be called cities (with estimated populations surpassing 10,000) could have meant increasing complexity in settlements where existing arrangements were no longer protected by family ties. On the other hand, some have also reasoned that the introduction of iron tools destroyed the royal monopoly on productive tools and thus also on affluence. At any rate, royal genealogies show that depositions and expulsions became increasingly common, and extant rulers had a newfound interest in emphasizing their lineage.

The burial record testifies to the increasing importance of military power in rulership. While earlier burials have contained weapons, the newest fashion in the 1st century BCE was apparently for weapons to be buried close to their users, and so there is generally a one-to-one relationship between subsidiary burials and weapons during this period. This is a revolutionary form compared from earlier practice, which placed hundreds of weapons into jars and buried them in the treasury of the ruler, in the sense that there are no transitional forms of the deposition of burial goods.

This pre-occupation with military capability in burial contexts could has been argued to symbolize royal insecurity, endemic during the Late Archaic. Others have firmly asserted that these military accoutrements also attest to the enlarging scope of royal authority as a city's defender, which is now firmly beyond a single extended family group. Those of the social history school has argued that the transition from the Middle to Late Archaic burial demonstrates that royal power not only expanded but also grew in humanity, treating those buried within the system of a royal burial not as chattels but as an integral part of the royal power. Thus, by the end of the period, the character of government had become distinct from possession, and a king was now a different kind of person than a mere slave-owning clan leader.

Classical Period (315 – 380)

While cities in the sense of physical settlement have existed for centuries, political power began to grow around the city during the Hexarchy, at the expense of clan leaders' powers. All six states experimented with redistributions of power between clans and states. Some created hybrid governments, like the Tsjinh, whose unity is often attributed to moderate policies, and others, like Kem, sought to concentrate power more absolutely. While Kem became a very powerful state, maintaining a standing army of several thousand, it was also isolated and opposed by the other states through alliances, whose ruling class feared loss of power and wealth should Kem's political system spread. Kem's reforms have shown a degree of Menghean influence and remained a major school of thought even after defeat.

In the 1st c. CE, Kem expanded to its maximal extent but was defeated by a coalition of four states in 51, practicing fabian tactics that stretched Kem's supply trains beyond their reach. Tsjinh was the chief beneficiary as Kem settlements and clans defected, with their lands and population, to it. The state welcomed the fealty of clan leaders and nobles, recognizing their autonomy for commercial freedom and troops. Some scholars believe the Tsjinh sought hegemony through economic volume, though this is not universally recognized. By 200, Tsjinh controlled half of Themiclesia-proper and led a four-state alliance, stirring up fear about Kem's intentions. It infiltrated the other courts with allies and married princesses to their courtiers.

Ultimately, Kem's fall came not from military weakness against a massive, hostile alliance, as its leaders feared, but geography. It needed tin from Sjin for its forges, but Tsjinh imported tin to improve irrigation, which made itself more productive and able to outbid Kem's offers in Sjin's markets. In 231, King Gawh of Kem reversed policy and sought to open new farmland to the north and east to compete with Tsjinh, but it did not progress quickly enough to erode their relative power. Instead, it provoked the aboriginal societies hunting and trapping there, who were traditional allies with Kem. Ensuing warfare required a navy, which further taxed dwindling mineral supplies. In 256, Kem capitulated to Tsjinh, resulting in the Treaty of Five Kings, which formally established the Tsjinh king as hegemon over all five states.

Ancient sources provide that the cultures of the states differed from each other. This is generally borne out by archaeological evidence.

Tsinh hegemony (380 – 432)

The Treaty of Five Kings was described in historical canon as the starting point of a dynasty that governed all Themiclesia, though this characterization shows heavy influence from Menghean historiography introduced in the 6th century. Diplomatically, the hegemonic system persisted through the 3rd century, the Tsjinh ruler requiring an annual meeting between kings where they endorse his position as hegemon. State borders were disarmed, and internal tariffs were reduced, but each state retained its government and forces. The Tsjinh hegemony was otherwise hardly perceptible.

Domestically, the Tsjinh state remained a patchwork of directly-governed (the demesne) and alienated land held by aristocrats; the demesne expanded primarily by colonizing new territory. A landless peerage was set up to combine the perceived virtues of aristocracy and bureaucracy; it granted a share of state revenue to bureaucrats, who would then have an interest in the state's stability and prosperity. Royal cadets also periodically received titles to settlements, though their fiefdoms usually smaller than non-royal ones, to protect the demense against alienation as much as possible.

While a meritocratic bureaucracy is said to have flourished under the Tsjinh, public access was restricted. Recruitment and promotion valued administrative effectiveness, but since were no public schools that spread literacy or taught aspiring bureaucrats, the requisite knowledge was passed from generation to generation.[1] By the 3rd century, families holding bureaucratic positions also became dynastic, obtaining vast tracts of land and hosting hundreds or even thousands of tenants and clients. The gentry class that later dominated Themiclesian politics begun in the Hexarchy but flourished under the hegemonic system. Ambitious commoners often started their careers as clients and earned their lord's recommendation.

In 317, King K.r′ang of Tsjinh (晉康王) sought to stem the increasing noocratic power, which was customarily nepotistic. Conceding that there was no way to break the monopoly on knowledge, he decided to systematize bureaucratic recruitment by asking the gentry of each prefecture to assemble and rank, by consensus, local candidates from First to Ninth Class. The recruit's future career depended on his showing here. An officer represented the crown and dissuaded bribery and intimidation. Each house granted a voice, the policy redistributed the inlfuence from more powerful houses to less powerful ones, making the crown popular in the meantime and limiting the most powerful of houses. Though a political device, it proved one of the most resilient institutions and gave rise to the House of Commons, fifteen centuries after initial implementation.

Pre-modern historians generally write of the Tsjinh period as one of great achievement, stability, and a political model for later dynasties. Even under the imperial order, dynasties paid lip service to the Tsjinh's hegemonic political order, symbolically erecting the palatine states as successors to the four states that politically dissolved in the 5th century and maintaining a peerage that was far less influential than it was under the Tsjinh. Some have criticized this image as romantic and assert that social mobility during the Tsjinh was extremely poor, and a commoner, even one educated, faced insuperable barriers in seeking office.

Sungh hegemony (432 – 492)

The Sungh (宋) dynasty replaced the Tsjinh though a bloodless coup in 420. The causes of this coup are not well-understood, though infighting amongst princes of the blood (諸子) has marred the throne's prestige in the late 4th century. The Antiquities of Themiclesia (震旦故事記) was presented to the royal court in 432, the oldest, surviving publicly-sanctioned historical work in Themiclesia.

Rjang (492 – 543)

The Rjang replaced the Sungh in 492 through a coup led by King Ngjon (梁元王), whose reign lasted nearly the entire dynasty. King Ngjon pursued military dominance across the palatine states, which were commanded to disband their forces. While the princes were willing to comply, their barons on the peripheries opposed the change. They conspired with each other, citing the Treaty of Five Kings, and pressured their princes to rebel in 497. King Ngjon anticipated this and went on the offensive, promising his barons were the rebelling barons' lands. Rather than allowing the barons' troops to lead his campaign, he interspersed them amongst peasant levies, which initially resulted in considerable gains. However, a defeat in 499 diminished those gains and opened the diplomatic phase of the war.

After a victory in early 500, he offered baronial leaders positions at his court and increases in their fiefs.

Meng (543 – 752)

Being the first dynasty to bear the imperial title in Themiclesia, the Meng (domestically, mrangh) court encountered an unprecedented need to assert itself as a legitimate continuation of the Meng Dynasty of Menghe. This dogma was to define the Meng court and shape many of its policies. Immediately after the abdication of the Rjang monarchy, Emperor Ngjon, who fled to Themiclesia after his home state Chollǒ fell, began reforming the Themiclesia to support his rule, with mixed results. In his construction projects, the court support him, but in concentrating more power in the throne, the court resisted. The Chollǒ aristocracy that arrived with him possessed few resources to fortify him and were more interested in re-establishing their economic position locally. Moreover, in Chollǒ, they were accustomed to a nominal ruler and did not desire to see change. To Emperor Ngjon's chagrin, they and the Themiclesian aristocracy entered a stable relatioship and jointly dominated government.

Under the traditional paradigm, shared by the Themiclesian and Chollǒ aristocracy, a dynasty that enjoyed the mandate of heaven should see tribute from other states. In Ngjon's reign, under pressure to prove his legitimacy, his sent emissaries with gifts to natives in Columbia with promises of more largess if they appeared in Kien-k'ang with a token tribute.[2] While Ngjon never meant this as a permanent measure, aristocrats' reluctance to use military power confined the dynasty's future rulers to this measure. As the number of tributary states rose, expenses mounted. In the 8th century, these expenses sometimes amounted to 30% of annual outlays.[3]

Dzi (752 – 1089)

The Dzi Dynasty was established by Tong Kruh-ljoi (董鋯陲) after a struggle for power against the final Mrangh emperor, Kjung (孟恭帝). In the respect of foreign policy, Dzi pursued expansionism and involved the state in intermittent warfare. Domestically, its politics was generally divided along the lines of the aristocracy (士族) and the commoners (庶族). The "commoners" refers to aristocratic but new clans that have risen to prominence during the second half of Meng rule. A smaller faction sometimes surrounded the Emperor, that did not belong to either group. Conflict between these two groups and the Emperor's struggle for power, defined the Dzi court.

While the Meng emperor protected his position by strategically appointing aristocrats, often creating debate and inviting input from the throne, the Dzi emperor sometimes circumvented his court in financial and military affairs. Organizationally, this translated to an expansion of the Inner Court.

One key development is the institution of the Themiclesian Navy, incorporated from the merchant marine that existed under the Mrangh, then having some diplomatic functions. The navy, unlike the army, was not funded by the public moneys, which were firmly under aristocratic control, but by the privy purse. Equally, revenues from the Navy flowed into it too. Additionally, since the Navy posed no threat to the land-based aristocracy, they generally did not interfere with its operation, allowing the emperor to field them according to his whims. Under Emperor M′jin (齊昏帝), the Navy was able to subjugate the Arokwa and Minuaka nations of Columbia and force them to do homage, as a second fork of the prime minister Gwjang Tjep's (王執) expedition to the continent.

Drjen (1089 – 1410)

Themiclesian Republic (1410 – 1507)

Civil War (1507 – 1531)

Modern Era

Geography and administration

Administrative divisions

Government

The Themiclesian political system is a modified Hadaway-style government. There is no codified constitution.

Executive

The executive branch is the Government. As a whole, it is politically responsible to Parliament and ceremonially to the crown. Because the House of Commons is the dominant house in modern practice, the Government must be able to maintain a working majority in this house to remain in power; the same is not as true of the House of Lords, without a majority wherein the Government may still govern. The Government consists of about 100 ministers, whose tenures in office is wholly dependent on its ability to maintain the confidence of Parliament. It is responsible for enforcing laws and issuing ordinances that are required by primary legislation.

The Cabinet, or domestically Council of Correspondence, is a committee of the most senior members of the Government. While there are subordinate ministers within the Government, the Cabinet is a council of peers. Procedurally, any Cabinet minister may put forth a proposal to make Cabinet resolutions, which are binding upon the entire Government, but all members of the Cabinet must assent to give it effect. The prime minister holds slightly more influence than his colleagues. Without a department of his own, the PM oversees interdepartmental policy, granting him more weight in general discussions; over a specific policy area, the responsible minister is expected to be dominant. If a lone minister cannot assent to a policy, he is expected to resign. If he is the responsible minister over the disputed policy, he has the option of asking his colleages to re-start discussions or to wait for further information; this option cannot be abused. If the Cabinet cannot come to an agreement internally or with Parliament, the Government also resigns by custom. Such a situation is infrequent, as most governments are composed of like-minded individuals.

Legislative

House of Commons

The House of Commons, or Council of Protonotaries, are elected by the people and represents their will in the political process. Because of the principle of democratic government, it is the source of political legitimacy and the chamber to which the executive is most frequently held responsible. The modern Commons, having taken shape of a legislative chamber in 1801, consists of 210 members directly elected by the first-past-the-post method in single-member constituencies. Both candidate and elector must be above the age of 18, of sound mind, not an undischarged bankrupt, and not a member of the armed forces. Currently, scholars of politics describe Themiclesia to have, primarily, a two-party system.

House of Lords

The modern House of Lords forms, together with the House of Commons, the Parliament of Themiclesia. The House of Lords consists of the peers of Themiclesia. Members are nominated by the Prime Minister and appointed by the Emperor; when a member dies, the seat is inherited by his or her heir as part of the title. Since the House of Lords is not democratically elected, it is by convention less powerful than the House of Commons. The Government may continue to govern without its confidence because it does not have power to reject spending bills. Since the end of the Pan-Septentrion War, the upper house has never rejected a bill, but it retains the function of debating measures passed by the Commons. Since it is not elected, some believe its views are less politically-motivated and may reveal shortcomings in the Commons' decisions to the public.

In case of an irresoluble difference between the two chambers over Government legislation, Lord L′ong-mjen's convention allows the prime minister to dissolve the lower house and seek a general election immediately. If the Government retains a majority, the upper house would pass the Government bill, or the prime minister may advise the sovereign to appoint as many peers as will carry the Government bill. This convention has limits: the lower house must be dissolved near the date of the bill's rejection that the ensuing election be a true test of public opinion upon the issue, and the prime minister may not seek to create more peers than would carry the bill. This convention has been successfully invoked only twice after 1900, once to pass the Income Tax Bill of 1905 and another time for the Conscription Bill of 1936. In every other case of disagreement between the two houses, one has relented sooner or later. Since the House of Lords does not usually challenge the Government save on controversial legislation, the threat of a general election called upon it has provided "a serious check on Government power" in the eyes of some commentators.

Judiciary

The judicial branch consists of the House of Lords, the Court of Appeal, and other high courts headed by the Supreme Court. Themiclesian jurisprudence is a mixed system that incorporates an existing canon of laws with many elements of Tyrannian common law. Courts of law may engage in judicial review to test the legality of devolved legislation and administrative decisions, but parliamentary statutes cannot be reviewed by the judicature.

Economy

The Themiclesian economy is founded primarily on the service industry, which accounts for over 64% of its national product; main services in which Themiclesia has a noted position internationally are those of finance, education, technology, business consultancy, and insurance. Nevertheless, the nation is still involved in agriculture and industry, but has focused, after the Pan-Septentrion War, on high value-added or specialized goods.

Agriculture

For most of its history, Themiclesia's economy was one of subsistence agriculture. Most dynasties openly promoted this form of production, sometimes even at the expense of suppressing commerce, as it fostered social stability and order by securing peasants to their land; this was further supported by land policies that protected a minimum allotment of arable land to each male and female subject. By the early 20th Century, high production costs meant it competed poorly with the industrialized agricultural market. Failing prices in agricultural goods forced many peasants to migrate towards the city, causing much unrest and tension, and also industrial wages to drop precipitously. In 1932, the government introduced a program to lease machinery to the peasantry, but it hardly made a dent until after the war. The traditional fishing industry also suffered a similar collapse, until an injection of funding in 1952 to modernize and revive it.

Modern agricultural in Themiclesia produces only a handful of cash crops, namely rice, wheat, and millet. The temperate climate of Themiclesia's heartland supports growing a wide variety of high-value cash crops, such as exotic fruits, premium vegetables, flowers, and spices. Themiclesia has a large fleet of fishing boats that utilize trawling nets to harvest the rich seafood that was previously inaccessible to manual divers and thus untapped. Further from coast, the natural current of the Halu'an Sea brings tuna and several other commercially viable species close enough to the coast that fishers do not need to brave the high ocean tides. Themiclesia's many long and peaceful rivers is also the reproductive habitat of salmon and herring. Inland lakes have sections closed off for the purpose of fisheries that produce halibut and sole, species suited to intensive farming.

Agricultural and rural tourism is now a hot topic and booming industry in Themiclesia. Service providers establish hotels and lodges in farming communities and provide the opportunity for tourists to acquire in-depth and hands-on knowledge of traditional agriculture; revenues from this industry is shared in co-operatives with the local community for perpetual development.

Mining and Industry

Themiclesia possesses a wide gamut of mineral deposits that command value on the international market, exploited since prehistoric times. With the introduction of modern technology, previously exhausted mines were re-developed in the 19th century; many investors value them higher than new mines, as existing shafts and tunnels could be re-used, drastically reducing the costs of initiating operations. Of these, copper and tin are the most intensively mined metals in this country. While Themiclesia may be one of the first users of a blast furnace, which creates cast iron, a key component of steel, this has never developed into a steel industry in Themiclesia prior to the modern period. There are uranium oxide deposits in Themiclesia, in the northeast of the nation.

Service, IT, and Finance

Demographics

Income and Income Distribution

Themiclesia produces roughly OS$1.86 trillion worth of value annually at the previous statistics announcement, for fiscal year 2018. Spread across the nation's population of 40.4 million, each citizen produces accordingly $46,000 of value; this is next to the Organized States of Columbia and (recently) Dayashina-proper. Income is distributed fairly equitably, with a Gini Coefficient of under 30.

Age

The average age of Themiclesians is 40, and this figure is set to increase on any ten-year outlook. The government is concerned if this trend is not corrected in the long term, but income shows a stronger correlation with age in Themiclesia than in other countries, as older people tend to be better-paid, which explains the relatively high retirement age in Themiclesia. The average retirement age in Themiclesia is 67.2 years.

Urbanization

Themiclesia is highly urbanized; over 80% of its population resides in urban areas. The most populous city is the capital city of Kien-k'ang, with a population of 2.65 million; counting the metropolitan area around it, around 8 million or 1/5 of the nation's population live close to the capital city. The second and third most populous are Ghwap-bo and Kwang-tshiu, each with 8 and 6 pepole residing in their respective metropolitan areas. There are 12 cities in Themiclesia with a population greater than 1 million.

Culture

Language

The official written language of Themiclesia is Shinasthana, though no law formally recognizes this. It is the de facto national language of Themiclesia, as it is the main language of instruction in primary and secondary schools as well as a mandatory subject in literature courses. This language belongs to the Menghic Family, sharing much of its vocabulary with the Menggok languages.

Aside from Shinasthana, various varieties of Menghean and Dayashinese are spoken natively by immigrants or their second- and third-generation descendants; they account for around 10% of the total population of Themiclesia. These two languages are also intensively studied by native speakers of Shinasthana, due to commercial and cultural relationships between these countries. Behind these two languages, Tyrannian is widely spoken as a second or third language by individuals of all backgrounds, but it is not usually a first language in Themiclesia. Rajian is spoken by a smaller but more distinct community residing in Themiclesia's far north, along the Nukkumaan border; formerly, it was farther north, but when Sngrak-tju was ceded to Nukkumaa in 1857, they decided to remain in Themiclesia.

Etiquette

Religion

Medicine

Records of illnesses are first attested in the Springs and Autumns of Six States, an anthology of divination records from 385 BCE to 256 CE. Oracles were used to identify the sources of complaints regarding parts of the body or the whole body, and sacrifices were performed to placate the soruce of the illness. For much of Antiquity, the curing of illnesses was deeply connected with divination and sorcery, which dealt with supernatural influences. A common ceremony associated with the removal of illness was Propitiation (禦), which was also used against omens like tilting roofs or falling musical instruments. Medicine as a secular discipline was first seen at the Sjin court in the late 2nd c. CE.

Foreign Relations

Armed forces

Themiclesia maintains standing and reserve forces to defend home territories and national interests, to fulfill military commitments to allied states, and to maintain international peace according to foreign policy. The Themiclesian emperor is personally the commander-in-chief of the Themiclesian Air Force, but the Emperor-in-Council, as head of the civil service, exercises ultimate authority over the Consolidated Army and Themiclesian Navy. In practice, the Cabinet acts as commander-in-chief, though the Secretary of State for Defence and junior ministers under him. The Ministry of Defence directly administers all the armed forces under the central government and indirectly those under prefectural or ethnic governments. The forces are conventionally divided into the three branches above, plus the Themiclesian Coast Guard, considered a fourth branch.

The Themiclesian forces slowly evolved from a nebulous and unconnected agencies, services, and units in the 19th century. Two-party politics stunted long-term leadership and broad reforms, while favouring piecemeal ones and creating new, dedicated units to address specific defensive needs. The absence of imminent external threats also contributed to this lethargy. In 1900, Themiclesia possessed one of the smallest (relative to population) and most fractured militaries in the world. In the 1870s, graduates of the Army Academy began building consensus amognst themselves and political parties to unify the army, fruiting only in 1921. While the forces are divided into the three conventional services, what constitutes a service branch remains very much a matter of custom and tradition. Each of the three services consist of a number of sub-branches with varying forms of autonomy from their parent service, from operational jurisdiction, to training and recruitment, to unit culture and uniforms, and to and rank and pay structure.

Notes and references

- ↑ "Appointment is at the royal court, but learning is in private houses" (簡在公廷,學在私門).

- ↑ According to state records, a single blade of grass was acceptable as tribute, since grass was used in filtering alcohol used at the Emperor's ancestral temples.

- ↑ In 732, the Secretary of State for Finance wrote to the Emperor, "[...] may it please Your Majesty, to have pity upon your subjects, when half their remission to Your Majesty is exchanged for silk, gold, and artifacts, made by tireless artisans who are not compensated for their services, and shipped abroad for the enjoyment of barbarous princes. None can doubt Your Majesty's great stature amongst the states and generosity to foreigners..."