Kembesa

Kingdom of Kembesa Ye'kembesiya Meseyoumeti | |

|---|---|

Royal Seal of the House of the Yegidonochi

| |

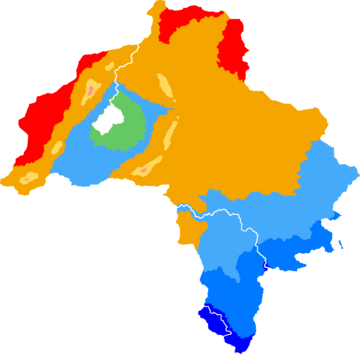

Map of Kembesa | |

| Capital | Azwa |

| Official languages | Kembesan |

| Recognised regional languages | Gharbaic Swahili M'bweni |

| Government | Confederal unitary constitutional monarchy |

• King | Selemoni XIV Gidoni |

• Lord Duke | Biniam Wolo |

• Speaker | Abreham Aklilu |

| Legislature | Royal Councils of Kembesa |

| House of the Rasochi | |

| House of the Commons | |

| Establishment | |

• Kingdom of Yebwi | 299 BCE |

• Christianization | 358 CE |

• Kingdom of Kembesa | 433 CE |

• Constitutional reform | 1948 CE |

| Area | |

• Total | 508,224 km2 (196,226 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 6.5 |

| Population | |

• 2018 census | 26,299,273 |

• Density | 51.75/km2 (134.0/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | estimate |

• Total | $491 billion (2018) |

• Per capita | $18,672 |

| Currency | Werik ( |

Kembesa, officially the Kingdom of Kembesa, is a country in Eastern Scipia. It is bordered to the north by Fahran, to the west by Charnea, to the south by M'biruna, and shares a maritime border across the Strait of Muketi to the east with Bemiritra in the Ozeros Sea. The capital city of Azwa is located in the country's north. Kembesans are the dominant ethnic group in the country, but there are major Gharib and Swahili enclaves within its borders.

Kembesan national identity is rooted in both linguistic and religious differences from its neighbours. The Kingdom of Kembesa became a Christian state in the 4th century CE. Over the next millennium and a half it remained independent from the Adzarin conquests and even the expansion of Mutulese Ochran. In the present, the Kembesan Orthodox Church is the state religion and is not in communion with Fabria. While a prosperous nation for much of its history, Kembesa declined in the 19th century. Under King Isaias III, the country liberalized in 1948, forming a constitutional monarchy.

The Kembesan economy is dominated by agriculture and mining sectors, exporting and importing goods north and south through Fahran and M'biruna respectively, as well as across the Ozeros. The country saw major a demographic expansion after the 1940's. Much of the country's power infrastructure was developed in that era and at present there is insufficient electrical production in many cities and villages.

History

Antiquity

Nomadic groups have inhabited the region of modern Kembesa for tens of millennia, though the oldest evidence of human settlement dates back to the fifth millennium BCE. The region fell under the influence of ancient Fahrani polities in the third millennium BCE. Speakers of ancient She'dje, the predecessor of modern Kembesan, formed the independent Kingdom of Ke'sem in the mid-10th century BCE. Ke'sem expanded over the next two centuries but collapsed around 750 BCE. For the next half-millennium warring states, each led by a Ras (duke), vied for power in the region. This era was known as the Rule of the Rasochi. Throughout this period, a king nominally ruled in Ke'sem, though the degree to which the Ke'semite kings exerted influence over the region waxed and waned.

The Rasochi were unified in 299 BCE by the House of Aizan which founded the Kingdom of Yebwi. The royal court was based in the ancient city of Me'lewa. The institution of the Rasochi was solidified in a permanent council, though the local rulers and the king were frequently at odds through this period and Yebwi succumbed to civil war numerous times in this era. The Aizanochi dynasty maintained power intermittently in the region until the 2nd century CE. During this era, Yebwi expanded and conquered the Tongo-Tongo Kingdom of M'bala to the south, expanding onto the coast and into the sphere of the Ozeros. When King Aizan VII died in 132 CE, the kingdom collapsed. King Girma V Endis consolidated his power in Yebwi, though M'bala wouldn't be restored until the mid-4th century CE.

Classical era

Christian proselytizers had ventured to Kembesa since the 2nd century, though it was not until after 320 CE when it became the state religion of the Latin Empire that missionaries began to arrive in droves, many from the Diocese of the East. While many local lords were hostile to Christians, the Ras of Anibesa accepted the first Christian community in Yebwi. As the faith gained traction in the region, the Ras was baptized as "Kaleb Yohoni" (known in Anglic as King Caleb John) and launched a war of unification which brought together Yebwi, M'bala, and the more arid northeastern reaches under the Christian Kingdom of K'idanibesa. King Kaleb I would be succeded by his son Kaleb II though the latter died without issue in 433 CE.

The Ras Nagash of Kaleb II's court, a man named Selemoni Gidoni (Solomon Gideon), received the assent of the Rasochi to assume the throne. King Selemoni came from uncertain origins and even the duchy he rules is lost to history. After assuming the throne, the legendary lineage of the judge and prophet Gideon was proclaimed. Prior to his ascension, Selemoni's identity and the location of his duchy are uncertain. Kembesan historiography regards the Christianization under the Yohonochi and early Gidonochi dynasties as the end of the classical era in Kembesa and the beginning of the middle ages.

Middle ages

Under the first Gidonochi rulers, the western borders of the kingdom were expanded into the realms of Hatherian Gharib tribes in modern-day Charnea. Prior to the accelerated desertification of the Ninva, several large towns existed in the region. By the 7th century CE, these towns relied heavily on fossil water in the ground but were still in decline. Even so, Kembesan rulers historically struggled to maintain their authority over these border regions. The rise of Azdarin in the latter half of the 10th century CE marked the beginning of a new era in Kembesa's history. Through Mubashir's reign, Kings Kaleb V and Kwastantinos I had to contend with Yen campaigns from the north. The latter experienced a great degree of success in repulsing these incursions and even gained ground after Mubashir's realm was sundered. After the proclamation of the Almurid Caliphate in 993, the Yen turned their attention to reclaiming lands lost to the Kembesans. After assuming the throne from his father in 1003, Kwastantinos II set about constructing a line of forts roughly along the line of the present-day border between Kembesa and Fahran. Hostilities between the Azdarin caliphates and Christian Kembesa persisted for centuries. Over the next three generations of Kembesan kings, the Kwastantinos Wall was reinforced in massive labour projects. To supply lumber for these projects, massive parts of the Me'balan jungle were deforested.

While the north was being shored up against the Yen, the expansion of the Tahamaja Empire to the south in the Ozeros posed another threat. Despite previous tensions with the maritime empire, the 11th century brought heightened hostilities and incursions by Kaiponu Tauā mercenaries, paticularly in the coastal swamps of southern Me'bala. Tahamaji settlers followed the mercenary warbands and set up forts and trading posts across the Kembesan coastline. The local Rasochi often tolerated or even cooperated with the Tahamaja, purchasing goods from across the Ozeros and selling their own goods for export as well. The Kembesan kings did not take the violation of their sovereignty lightly. Tahamaji forts were often sieged and captured by Kembesan land armies, only for Tahamaji fleets to retake them, perpetuating a rotation in custody of the forts. The Siriwang eruption at the end of 1353 ushered in the end of the Tahamaja empire. Most of the forts were destroyed by the tidal impacts of the blast. While the eruption wrought immense destruction in Me'bala and even into Ye'wenizi, in the kingdom's heartland of Degama the event was seen as divinely inspired. King Gidoni XII was canonized by the Kembesan Orthodox Church within his own life, a process which drew the ire of the church in Fabria and other Christian denominations.

Despite deteriorating relations with its historic allies, the generations following the collapse of the Tahamaja Empire were a golden age for the Kingdom of Kembesa. Despite the expansion of the Imuhaɣ up to the western borders of Kembesa in 1360, relations with the caliphates to the north normalized following the concession of post-Tahamaja Barriset to the Yen and the opening of trading routes. However, the warming of relationships between the Christians and the Yen was short-lived. The first edict that King Mika'eli VII issued upon his ascension in 1421 was to ban Yen ships from docking in Kembesan ports.

Early modern era

In the first part of the 16th century CE, Mutulese merchants and explorers expanded their influence to Ochran and eventually the southern reaches of the Ozeros by 1560. Two decades later and Mutulese influence in Barriset was growing. The new merchants received tacit rights to trade with Kembesa, bypassing the laws which discriminated against the Yen. The increasing influence of the Mutulese on Barriset and the erection of White Path temples angered the local Azdarin clergy who called for any worship aside from 'Iifae to be banned. The caliph's governor conceded to the demand, but was forced to retreat from it after protestation from the Mutulese who raised militias and warships as a threat. An insurrection of 'Iifae imams proclaimed their own caliph and led a war against the original governors and the Mutulese. By 1661 CE, the Mutulese officially undertook the administration of the island and proclaimed the Yajawil of Barriset.

During this period, the Kingdom of Kembesa became concerned by the expansion of Mutulese power. In 1646, King Isayasi I attempted to ban the presence of Mutulese traders in Kembesan ports after their victory in the First Shamabalese Great War. However, Mutulese merchants flaunted the laws and local dukes and administrators overlooked them out of fear of reprisals from the foreign traders. Fearing further expansion and marginalization, the Christian rulers of Vardana entered into a secret pact with the Imamates in 1667. King Gidoni XVI was thereafter persuaded to join the alliance against the Mutulese before the Ozeros War began in 1670. Kembesan knights and soldiers joined the Vardanan intervention on the Island of Barriset, landing and helping to establish a beachhead in the north. Poor communication and weather led to the Christian forces being caught unawares and repelled from the island, however. King Gidoni XVI was killed in the retreat while leading his men. The late king's son, Gidoni XVII, continued to prosecute the war against the Mutul, but Mutulese reinforcements from further south in the Ozeros forced the Christians to abandon the blockade of Barriset. Piracy and naval skirmishes persisted against the Mutulese for a number of years with little effect. In 1677, the Treaty of Samosata was signed leaving Barriset under Mutulese control and allowing the destruction of the 'Iifae Imamates.

Modern era

The late-17th and early-18th centuries in Kembesa were relatively peaceful, though the kingdom fell from prominence in the region compared to trading hubs to its east and north. Free from external conflicts, a succession of kings invested in civil works including castles and palaces but also paved roads and aqueducts. In 1711, a plague broke out which crippled the central regions. Thousands were killed before the epidemic broke in the late 1710's. While modern scholarship suggests that the disease was caused by local water contamination which spread through the newly constructed aquiducts, King Biniam IV apportioned the blame to foreigners and ordered the closing of Kembesa's ports and borders. The Tebaki'seyoum (Elect Guard) were reformed from the king's household guard to a standing army and separated into detachments to protect the borders with Fahran and M'biruna and to enforce the port closures despite the protests of the local Rasochi. In July of 1734, a cabal made up of over a third of the Rasochi executed a plot to overthrow King Biniam. Tebaki'seyoum barracks were burned in Arwas and Kima. The region of Me'bala effectively seceded from the kingdom as the local rulers appointed a Ras Tilik'u (Grand Duke) to lead the revolt. The civil war continued for several years before the leaders of the revolt were captured in 1737. Over 30 nobles were executed and condemned to have their names forgotten. Pockets of resistance to Kembesan central rule continued to cause problems for the state into the 1750's.

The next emergency to strike the Kingdom of Kembesa was the mobilization of Charnean tribes in the Ninva. The northwestern borderlands and control of the Hatherian settlements had been taken for granted for centuries. The onset of the warring states period of Charnean history saw the Hatherian settlements fall under foreigh control and eventually the Charnean Empire. Imuhaɣ warbands descended from the desert and raided Kembesan settlements. By the time the royal and ducal forces could be mustered, the capital of Me'lewa was nearly overrun. King Biniam V fled with his court before the royal palace was burned in the Fall of 1758. The royal court was reestablished in Azwa in the next year. The northern parts of Degama were retaken in the early 1760's but the new capital remained in Azwa to the present day.

The subsequent century brought on the first waves of industrialization across the world. Howver, Kembesa remained relatively isolated from these changes; serfdom and manual labour remained the dominant economic modes. Early steam engines and mechanization rarely permeated Kembesa's borders. Furthermore, departures from the traditional ways of life for peasants and serfs could be sanctioned by the church.

Contemporary history

In the 20th century, Kembesa began to face mounting internal an external pressure to liberalize. King Mika'eli X was assassinated by a serf abolitionist movement. King Gidoni XX suceeded to the throne and created a secret police detachment in the Tebaki'seyoum. The crackdown on dissidents was harsh but was followed by an era of industrialization. Electricity became more broadly accessible in the 1930s after a series of ambitious hydroelectric projects. Several of the dam projects had severe environmental impacts and displaced thousands of serfs, especially in Ye'wenizi and Me'bala.

Geography and climate

Kembesa is a country of hills and rivers. Tropical forests and highlands cover most of its area. The Kira River, which extends from Kembesa, through Fahran, Alanahr, and into the Periclean Sea, flows from Lake Gozzam, itself fed by several hundred rivulets in the Degama Region. The highest point in that Kingdom is at the peak of Mount Anibesa in the western reaches of the Degama Region. The greatest climatic variances are found in the Ye'wenizi region where tropical forests and marshes give way to savannah plains and even some areas of desert.

The Me'bala Region, which includes most of Kembesa's coasts, sees the most consistent rainfall of the three regions. The monsoon season is mitigated somewhat by calm winds and waters afforded by the island of Bemiritra which protects Kembesa's northern coasts from the open waters of the Ozeros. As the country is located in the northern hemisphere, most of its rivers drain southward toward the equator and the Ozeros. Much of the southern coastal area is saturated marshland.

Temperatures in the country vary by season and location. In Ye'wenizi and Me'bala, seasonal temperature variations are extremely low, averaging less than 5 degree centigrade. However, rainfall is very different. The more eastern and northerly region experiences more dramatic dry and rainy seasons. Most of the precipitation only falls in the midsummer. Ye'wenizi, by contrast, experiences steadier rainfall, though the summer months are considerably wetter than the winter. In the west, the Degama Region experiences a multitude of microclimates owing to the inconsistent mediating effect of water systems, valleys, and small rain shadows. Seasonal temperatures exceed those in the other two regions and can vary between 10 and 15 degrees centigrade seasonally. The rainy season is also about as long as it is in the Ye'wenizi Region - about 7 to 9 months of the year.

Government and politics

Branches of government

The Kingdom of Kembesa in a confederal unitary constitutional monarchy. That is to say, it operates as a confederation of unified regions in which the central government has ultimate authority and a constitution defines roles for both the monarchy and democratic institutions. In effect, the monarchy and the traditional nobility of Kembesa wield the majority of the power. The commoners, the nobility, and the monarch are each represented in the tricameral parliament known as the Royal Councils of Kembesa. Any bill must receive the assent of all three houses to be enacted as law. The upper two houses (the Rasochi and the monarch) also enact the judiciary and executive functions of the government.

The lowest house is the House of the Commons. The Commons is made up of 150 representatives divided evenly among the 3 regions. Representatives are elected proportionally through a party list system in each region. A Speaker is subsequently elected by the Commons. Terms in the Commons last 8 years.

The House of the Rasochi (dukes) is the middle-to-upper house of the parliament. There are 62 seats in the house, one for each duchy. The title of Ras is hereditary and the monarch surrendered the right to unliaterally appoint new members to the Rasochi in the 1948 constitution. Instead, both the Rasochi and the monarch must assent to any new members. The House of the Rasochi is also the highest court of the Kingdom. In this function, the monarch keeps a panel of three Rasaki Danya (Ducal Arbiters) to hear cases. The monarch also appoints a Ras Nagash (Lord Duke) to manage the affairs of the house. Both the Ducal Arbiters and the Lord Duke serve 8-year terms before the monarch must make another appointment.

Though often not considered a house in the same sense as the Commons or the Rasochi, the Royal House of the Yegidonochi completes the tricameral structure of the Kembesan government. The monarch themself executes most of the functions of the house in providing or withholding assent for bills and functioning as the head of state. The monarch also appoints advisors and officers for the functioning of the executive branch of the government. In general, the monarch has a great deal of discretion in how they organize their government, though there are constitutional limits placed on their ability to make unilateral orders. Outside of the executive function and the ability to make appointments, the monarch has no unilateral means of enacting law.

Law

Kembesan law is a patchwork of customary, religious, and statutory laws. Royal edicts and bills passed since 1948 form the basis of the statutory regime which applies across the Kingdom, mostly in the domain of criminal law and public safety. While the Kembesan Orthodox Church has little official influence aside from a customary executive appointment from the monarch, Kembesan canons and ordinances inform many customary laws and according to precedent they hold legal authority. Customary laws are usually unwritten and specific to certain regions and duchies. They can cover different legal areas including tort law, morality crimes, and property. In these areas, the court system has generally preserved local traditions rather than impose a single law across the Kingdom.

Administrative subdivions

The Kingdom of Kembesa is divided into three kililochi, or regions which represent cultural, linguistic, and geographic polities. The three regions are Degama in the west, Ye'wenizi in the east, and Me'bala in the south. Each region admits 50 representatives to the House of the Commons. The area of the Kingdom also encompasses 62 ye'ras meretochi, or duchies, the borders of which do not readily correspond to those of the regions. Municipalities and incorporated communities must be established through tripartite assent between the Royal House, the House of the Rasochi, and the House of the Commons. As a result, only 5 new municipalities have been incorporated since the induction of the new constitution in 1948 and many people reside in unincorporated communities.

Military

Economy

Kembesa has a mixed economy with heavy reliance on agriculture and resource extraction. Subsistence activities also make up a significant part of the economy. Over the past decade, economic growth has stagnated but thus far an outright crash or recession has been averted. Present-day challenges include an insufficient electricity grid and barriers to movement. Income inequality is high with the vast majority of wealth concentrated with a small segment of the population. Over the 20th century, Kembesa's rapid population growth was a major driver of its economy but also a massive burden upon its infrastructure. Liberalization in the mid-century formally redefined property rights and private industry, but the substantive ordering of the economy resembles the pre-1948 status quo to the present day.