Easter Revolution

| Easter Revolution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the aftermath of the War of the Triple Alliance | |||||||

The burning of the Katterburg palace by the revolutionaries at the height of the revolution. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 130,000 |

150,000 (de jure) 20,000-40,000 (de facto) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 468 killed, 4,579 wounded, and 96 missing | 4,683 confirmed killed and buried; unconfirmed estimates between 8,000 to 10,000 killed | ||||||

The Easter Revolution (Weranian: Osterrevolution) sometimes known as the Wiesstadt Uprising (Wiesstädter Aufstand) was an anti-monarchist insurrection in Werania that occurred in 1856 from 27 April to it's suppression on the 19 June. Occurring in the aftermath of the War of the Triple Alliance it is generally considered to be the last major revolutionary action to establish a republic in Werania in the 19th century and its suppression heralding the end of the process of Weranian Unification.

The War of the Triple Alliance had radicalised the Weranian working class who endured widespread devastation wrought by the nations of the Triple Alliance, rapidly rising bread prices and high war taxes. The Torrazza Accords which were signed to end the war were not seen particularly by Weranian republicans as sufficient for the sacrifices Weranians had given to the war leading to the famous writer Bastian Fischart to call for patriots to "throw off the shackles of this Torrazza peace" to establish a revolutionary republican government. Although discontent of the Torrazza accords gave impetus for the revolution stagnant living conditions, a desire for political reform, the unpopularity of King Adalbert and republican agitation led to the conditions for the revolt.

The immediate cause of the revolution was the Tuesday Massacre when protesters in Westbrücken were suppressed by the National Guard who killed 21 people. Similar protesters backed by the police and army units stationed in the city soon stormed the Katterburg palace in Wiesstadt where they declared a revolutionary government. The veteran revolutionary Sebastian Mertz was given extraordinary powers to oversee the defence of the revolution as the revolutionaries began assembling forces to secure the rest of the country.

The Easter revolutionaries came from a broad spectrum of ideologies - although traditional republicans dominated the revolutionary government itself feminist, socialist, and anarchist elements were also present. The revolutionary leaders were mainly intellectuals, journalists and writers with only three figures - Mertz, the former head of the Wiesstadten garrison Fabian Vogelstein and the exiled Vedmedi revolutionary Ioseb Cherkezishvili - having substantial military experience. A falsified report that the revolutionaries had killed cardinal Conrad Clemens von August turned public opinion in the provinces hampered the revolutionaries appeal, leading to the Weranian government to seize the initiative and dispatch 130,000 troops under the command of Adolf von Hoetzsch to crush the rebellion.

Von Hoetzsch's strategy was to utilise attrition warfare to permanently destroy the revolutionary forces. This strategy backfired as the revolutionaries instead gained popularity being able to mobilise more volunteers. However an inability for the revolutionary leadership to organise an effective fighting force hampered their counter-offensive against von Hoetzsch's forces, particularly as there was infighting within the leadership. The burning of the Katterburg palace - the symbol of the monarchy - galvanised Adalbert to order von Hoetzsch to crush the rebellion more promptly.

Government forces would retake the city by mid-June with many revolutionary leaders either being killed or fleeing to Azmara. The subsequent repression of revolutionary forces by von Hoetzsch led to up to 10,000 deaths making them some of the worst massacres in east Euclea in the time period with women and children also being executed. The suppression of the revolution led to republican and socialist politics to decline in the following decade, emerging again in a less revolutionary form in the 1870's when the Weranian government issued an amnesty to the revolutionaries.

The revolutionaries in their brief time in power experimented with a wide range of policies ranging from the prohibition of child labour, the abolition of organised religion, the right of employees to take over an enterprise, the granting near equal rights to men and women and the restoration of the republic. The short lifetime of the Wiesstadt revolution however meant many of these policies remained only partly fulfilled.

The revolution and its failure would play a role in influencing socialist and republican thought in Euclea, notably for Weranian socialists Bastian Fischart and Ludwig Vollmar who directly participated in the revolution but also Yuri Nemtsov, xxx and xxx.

Background

Weranian Unification had been completed in 1842 through an alliance between the Cislanian monarchy under Rudolf IV and his minister-president Ulrich von Bayrhoffer and an assortment of radicals and republicans such as Klemens Müller and Sebastian Mertz who were members of the Septemberist secret society that advocated for a restoration of the Weranian Republic. The process of unification meant that the unified state was a federal monarchy rather then the unitary republic favoured by many Weranian nationalists. Nevertheless Rudolf IV's adroit management of the political system was able to ensure that a liberal, anti-clerical majority where able to govern placating republican sentiment. Rudolf IV's successor, Adalbert, was more absolutist in his character but unlike Rudolf IV was more supportive of annexing the Eastern Marches of Kirenia (Zinngebirge basin, Garz, Zittau, Delland and Ruttland), areas coveted by Weranian nationalists.

Adalbert's pan-Weranic views were informed by his belief that if Werania was unable to annex the Eastern Marches republicanism amongst the burgeoning middle classes would increase and that by decisively defeating Kirenia the Cislanian monarchy would secure its status as the representative of the Weranian people as a whole. This diagnosis was shared by the centre-left within the Bundestag led by von Bayrhoffer who Adalbert restored to the premiership shortly after his coronation. Of particular note was the widespread perception that large elements of the military supported a republican government modelled on that of Balthasar Hötzendorf's "republic of colonels" that governed Werania during the revolutionary wars. Many members of the military were former members of the Central Revolutionary Federation, commonly known as the Septemberists, who had spent much of the pre-unification period agitating for revolutionary action to achieve unification.

Post-unification Werania was marked by a discrepancy between the rural countryside and rapidly industrialising urban centres. Urban centres were seen as bastions of republicanism with the middle classes and proletariat fondly remembering the legacy of the republic and resenting the conservative order imposed on Werania in the aftermath of the revolution in the 1810's. The cities also tended to have stronger feelings of a shared Weranian identity due to the influx of Weranians from different parts of the country into them as they rapidly expanded. Urban centres such as Westbrücken, Wiesstadt, Ostdorf am Main, Gothberg and Frankendorf had been major centres of revolutionary, republican and nationalist agitation in the pre-unification period. Comparatively rural areas remained more conservative due to the continued influence of the Solarian Catholic Church, higher rates of illiteracy, greater provincialism and negative memories of the republican period which was remembered more for the violent suppression of monarchist sentiments and the destructive effects of the massenaushebung.

Republicans and revolutionaries

Following unification republicans continued to remain politically active. In the Bundestag they sat in their own parliamentary group, the far-left Republican Bloc whilst they remained influential in the public sphere in their Wiesstadt-based newspaper, Der Herold. The traditional republicans were mainly based in Westbrücken, the historical centre of radical politics in Werania, but were divided between a more revolutionary and reformist faction. The reformist faction, which was stronger within the Bundestag, supported the creation of a federal republic based on Asterian nations such as Ardesia and Marchenia, essentially replacing the monarchical federal presidency with an elected president, whilst maintaining a liberal and anti-clerical position. The revolutionary faction, influential in Der Herold and amongst army officers, was more appraising of the old republic supporting the restoration of a centralised, radical regime predicated on dirigisme and the Cult of Rationalism.

Whilst traditional republicans were more influential in elite circles newer strains of radical republicanism were emerging as Werania industrialised. Socialist movements had begun to emerge across Euclea as activists and writers began to criticise the inequality and social deprivation associated with industrialisation. Early Weranian socialists generally were utopian in character based on advocacy of meritocracy and social and economic relations based around consumers' co-operatives rather then profiteering. Utopian socialists such as Fritz Möhring also influenced the early trade union movement which tended to be radical in their demands for workplace militancy but less ambitious in terms of broader political reform.

A key figure in the development of socialist republicanism in Werania was the writer Bastian Fischart. Fischart had come to prominence in 1843 for his play I. Amort but had become by the early 1850's an increasingly influential social critic who abhorred what he saw as the moral failings of the unified Weranian state. His 1855 continuation of Amort was noted to comment more broadly on social phenomena reflecting Fischart's increasingly left-wing views. Fischart in the 1850's was a regular writer at Der Herold and advocated for a synthesis between the revolutionary republican politics dominant within intellectual circles with socialist ideas of worker militancy and the creation of a "social republic". Fischart's advocacy of a republican-socialist union helped introduce both socialist ideals to the republican movement whilst encouraging socialists towards more revolutionary action.

Fischart's protégés such as Ludwig Vollmar went further in this synthesis calling for workers' organisations to become the basis for revolutionary action and for the creation of a räterepublik based around workers' councils, a forerunner to syndicalist and councilist ideologies. Vollmar was credited for helping create a network of cells within worker movements around Werania in the 1850's that were trained and armed a professional revolutionaries based on the Septemberist model whilst being embedded into worker movements.

Additionally Werania's relatively liberal political climate compared to its neighbours meant particularly in its urban centres it hosted members of nationalist diasporas exiled from their homelands which were ruled by foreign powers. Most notable of these in Werania were people from the Soravian Empire, predominantly Vedmedis and Miersans. These individuals were often close to the republican movement who often supported their independence from Soravia and Gaullica and were considered to be amongst some of the more professionalised revolutionaries in Werania.

The rural to urban migration encouraged by industrialisation and terrible living conditions for workers' in most major cities made the spread of socialist ideologies more pertinent throughout the late 1840's and early 1850's. Trade unions were strictly illegal and in many cases employers often utilised violence to destroy them which helped lead to revolutionary groups such as Vollmar's "neo-Septemberists" gain more leeway due to their secretive nature over reformist groups. Many workers' supported a more just way of managing the economy and alleviating social ills. Whilst they didn't necessarily support the precise goals of the republican and socialist movements these movements were able to articulate worker discontent with the status quo and the failure of the Weranian government to improve social inequality.

War of the Triple Alliance

The spectre of a social crisis engulfing Werania alongside widespread support for pan-Weranicism meant that in April 1852 Adalbert and von Bayrhoffer engineered a diplomatic crisis with Kirenia with a proposal to create a condominium in Ruttland. When this triggered widespread rioting across Ruttland the Weranian government issued the Elmsberg ultimatum that demanded the entirety of the Kirenian Eastern Marches, an ultimatum Kirenia rejected leading to Werania to declare war on the former on the 24 May 1852. The declaration of war against Kirenia led to the republican and pan-Weranicist movement to temporarily support the government - the republican legislator Reiner Neuhäusser commented upon the news

"What a joy! What a delight! We are on the cusp of righting the wrong of 1801, of finally ending the unbearable fiction of Kirenian sovereignty of Weranians. Werania did not wish for war, but it is now our solemn duty to prosecute it with the utmost enthusiasm and rigour until the corpse of Kirenia lies at our feet."

The Weranian army would in the initial months of the war win decisive victories over Kirenia prompting the latter to activate the so-called "Triple Alliance" of itself, Gaullica and Soravia which itself prompted Estmere to enter the war in support of Werania. Ultimately the war would last for three and a half year from May 1852 to December 1855. The decisive defeats of the Soravian army at the battle of Trierbeg and siege of Rokrika would lead to the latter to conclude a white peace leading to the Triple Alliance to lose their numerical advantage resulting in the war to enter a stalemate between the Gallo-Kirenian and Estmero-Weranian forces. Attempts to break the stalemate such as a failed attempt to goad Etruria into joining the war (known as the Augsberger Affair) led to the two sides to after the inconclusive siege of Aimargues organise a conference in the Etrurian city of Torrazza to determine an equitable peace between the powers.

Prelude

Congress of Torrazza

The Congress of Torrazza, presided over by the Gallophile King Caio Onorio and Weranophile premier Leopoldo d'Azeglio, was fraught with difficulties in terms of coming to a just peace. In practical terms the Estmero-Weranian forces had defeated the Gallo-Kirenians but as the Gaullican army still remained strong in the field the Gaullican government insisted it would not pay an indemnity nor oversee large scale territorial transfers. Premier von Bayrhoffer had prior to the congress boasted that Werania's success on the field entitled it to the entire Eastern Marches of Kirenia stating any other outcome would be farcical. However the reliance on Estmere in the latter stages of the war alongside the more skilled diplomacy of [Lord Crumpet] and the [duc de Baguette] meant that these demands were seen as unreasonable by other members of the congress.

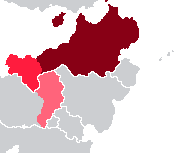

Ultimately Werania would gain from the war the entirety of greater Ruttland (modern day Ruttland plus the Zinngebirge Basin located in modern-day Kirenia) whilst Gaullica ceded Hennehouwe in return for Gaullica and Kirenia paying no indemnity and Werania disavowing the use of force as a method for gaining territory in the future. The Torrazza Accords as they became known were seen by the nations of the Triple Alliance as excessively generous to Werania whilst both Adalbert and von Bayrhoffer saw the territorial acquisitions as sufficient to ward off criticism from republican opposition. Shortly after their signing foreign minister Ludwig von Augsberger confidently predicted that "with the Torrazza Accords we can be sure that the republican protestations will have exhausted themselves".

Radicalisation of the workers'

During the war the Weranian government implemented a variety of measures to sustain the war effort including the raising of war taxes and control over food distribution via rationing. During the war the population of urban centres suffered from shortages of food, firewood, coal and medicine especially as conscripts were raised to defend strategic points. These shortages led to worsening living conditions - during the war itself an outbreak of cholera decimated Wiesstadt leading to 10,000 dead and arousing further discontent with the federal government. The war also saw the government harshly repress domestic dissent censoring the press and repressing workers movements which protested about the rising costs of rent and bread.

The activation of the conscript system meant that by the end of the war there were many working class men armed and trained (albeit poorly) in military drill. Those in cities such as Wiesstadt which had avoided much of the war were radicalised by the increasingly poor working conditions and repressive government attitude, a sentiment exacerbated by the calls from revolutionary factions to oppose the Weranian government. As well as this there was an exodus of upper and middle class people from the cities during the war to the countryside whilst refugees and army garrisons went into the cities, further leading to a base of armed and radicalised groups within urban areas.

The government had during the war operated an effective propaganda network that had sustained consistent public support for the war effort despite government repression. However this propaganda often led to supporters of the war effort to have unrealistic expectations of the gains Werania would secure in the event of a victory, with the feeling that Werania would annex the entirety of the eastern marches being seen as all but assured, a sentiment buoyed by republican and radical voices lending conditional support to the government.

The resultant Torrazza accords were seen as a capitulation by much of the population who saw their signing as a reversal of promises made during the war in particular to the demands of Gaullican and Estmerish negotiators. Der Herold in particular criticised the Torrazza accords as a "disgrace" with Bastian Fischart writing -

"Once again the narrow bourgeois mentality of von Bayrhoffer and his tragicomic liege Adalbert has denied the Weranian proletariat in Kirenia the liberty they have fought for in favour of maintaining bondage to Estmerish aristocrats...it is only natural that we patriots feel betrayed by this continued spurning of the people. But it is not enough to simply state our opposition to this dreadful state of affairs. Patriots - who believe in the values of Werania and the revolution, freiheit, gleichheit, brüderlichkeit - we must throw off the shackles of this Torrazza peace and restore our rightful freedoms! Long live Werania, long live the republic!"

Public discontent was soon voiced through a series of protests held throughout Werania, mainly in its cities. These protests were seen to effect the results of the 1856 federal election - the Republican Bloc won the most seats in urban areas seen as evidence as a repudiation of the Torrazza accords and the general unpopularity of the monarchy. The limited franchise overrepresented landowners however meaning the republicans remained a minority in the Bundestag with conservatives dominating the assembly which further exacerbated tensions between republican and radical elements and the political establishment.

In these early protests although revolutionary elements were active they were relatively unorganised at this stage being unable to convert the protests into actual revolutionary action. Most of the prominent republican and revolutionary figures congregated in Wiesstadt due to the city holding the offices of their mouthpiece, Der Herold, rather then Westbrücken were republican and radical sentiment was strongest.

Tuesday Massacre

Continued protests in Westbrücken shortly after the holding of elections saw protesters issue a series of demands to the federal government to stem the now widespread discontent with government policies. These demands included but were not limited to the immediate resignation of von Bayrhoffer and his entire government, the repeal of wartime taxes, a moratorium on outstanding rents and a repudiation of the Torrazza Accords in favour of the unilateral annexation of the entire Eastern Marches. The protesters assembled outside the Bundestag to voice their demands, although where generally not seen as possessing a republican or revolutionary agenda.

Nevertheless the Weranian government panicked, believing the demands particularly for the resignation of von Bayrhoffer were cover for the start of a republican insurrection. Generalfeldmarschall Karl von Littitz, the inspector-general of the army, warned Adalbert that he could not confirm all elements of the army would support the monarchy in the event of an attempted republican coup and recommended that the government make an example of "rabble rousers" to assert its authority. Von Bayrhoffer who suspected that Adalbert was already aiming to remove him from power was eager to assert his authority and so authorised the head of the city's military constabulary Josef Kronthaler to send in troops to suppress the protesters.

Kronthaler sent the heavy cavalry to break up a crowd of 300 protesters on the 22 April 1856. The cavalry killed 12 people and injured many more leading to the protesters to disperse as Kronthaler also order other members of the military constabulary to break into republican haunts arresting anti-government activists. The "Tuesday Massacre" as it became known inflamed public opinion with anti-government papers and activists harshly criticising the government which was increasingly labelled as dictatorial. The government scrambled quickly to attempt to crackdown further on anti-government sentiment but was unable to control public opinion in other urban centres which were increasingly becoming revolutionary in character. Far from assert their authority the Westbrücken crackdown was seen to do the opposite showing the brittle nature of the governments support and its increasing reliance on the politically divided army to maintain power.

Establishment

Seizure of Wiesstadt

The Tuesday Massacre incensed the population across Werania with large scale protests being held in every major city across the week. Outside Westbrücken protests were strongest in Wiesstadt where the deliberating cholera outbreak during the War of the Triple Alliance had decimated support for the government and where the mayor, Olaf Krieger, was a liberal sympathetic to the radicals. The republican journalist Artur Schönfeld in the Wiesstadt-based radical paper Die Stimme der Elenden called for an "atmosphere of rage" to permeate the population until the government was displaced and replaced with a radical administration. The government responded on the 24th April to ban seventeen radical and republican papers including Der Herold, the majority of which were based in Wiesstadt and Westbrücken.

Believing the revolutionary threat to be greater in Westbrücken von Bayrhoffer declared martial law in the city and sent the military constabulary to raid the offices of radical papers. Meanwhile the authorities in Wiesstadt moved more slowly due to a belief that the revolutionary movement was smaller and the failure to realise that key republican and radical leaders were now based in the city and actively politicising elements of the population and armed forces. The commander of the Wiesstadt garrison, oberst Fabian Vogelstein, wrote a letter to the central government on the 25th April that was intended to warn them that the forces stationed in the city were almost entirely compromised in terms of their loyalty to the government but the letter was never delivered. Of the 204 battalions stationed in the city each consisting 1,500 men each (a total of 306,000 overall) Vongelstein estimated that around three quarters of that number were politically compromised.

On the 25th mayor Krieger unilaterally ordered the evacuation of the Cislanian government and members of Landtag from the city in fear of their safety. Krieger's decision was heavily criticised by the central government and only a fraction of both the government and the landtag left the city believing Krieger fears to be overblown. The president of the Landtag, the conservative Konrad von Blumenfeld, however was amongst those who were smuggled out the city declaring that the Landtag's official duties would be undertaken in the neighbouring city of Siegberg whilst revolutionary unrest continued to engulf Wiesstadt.

On the 27th April at midday members of the Wiesstadten police fired on protests in the Charlotte-Marie Square in central Wiesstadt. In the confusion that followed numerous members of the military garrison deployed in the city turned on their commanders and joined the protesters. Protesters soon descended on the Weißenhaus which housed the Cislanian Landtag taking its members hostage with the deputy commander of the garrison Moritz Gottlieb declaring them hostages of a revolutionary government. The seizure of the Weißenhaus led to other units of the army and military constabulary to seize positions around the city including government offices, the mayor's mansion and the railway station. At the Weißenhaus the military units officially formed a revolutionary committee of 19 members to temporarily administer the city.

The revolutionaries position however hung in the balance as they had not seized the headquarters of the city garrison which was still under the command of oberst Vogelstein whose position to the revolutionary demonstrations was still unclear. At around 2 o'clock Vogelstein agreed to meet representatives of the revolutionary committee to discuss the status of the garrisons position. Vogelstein was himself a political moderate considered neither to be a conservative or a republican but was deeply struck by the extent of republican and radical sentiment in the army and the anger felt by his charges towards the political establishment. In a move that surprised observers Vogelstein declared he would offer his services to the revolutionary forces unconditionally due to his perceived duty to remain loyal to those under his command. Vogelstein's position wrongfooted those within the garrison who had hoped he would crush the rebellion and led to the conservative units within the military and police garrisons to become confused enabling revolutionary units to easily neutralise them.

Vogelstein and Gottlieb as the heads of the military garrison were as such the de facto dictators of the city which was still beset by revolutionary violence. The revolutionary committee quickly reached out to the radical press and prominent republicans to serve in a larger council of bezirke to be formed through a mixture of elections and appointments. At this stage the revolutionary committee was unclear as to whether its purpose was to serve as an alternate city administration, a replacement for the now partly exiled, partly imprisoned Cislanian government or as a springboard for a more national revolution for the country.

The next day on the 28th saw the revolutionary militia's go throughout the city shutting down conservative papers, occupying churches and disarming soldiers suspected of harbouring anti-revolutionary sentiments. Weranian flags were torn down from government buildings being replaced with the republican tricolour or red flags, often emblazoned with "freiheit, gleichheit, brüderlichkeit". Many of the revolutionary militia's introduced officer elections which saw the garrison of the city fully converted into supporters of revolutionary action. On the morning of the 28th additionally the Archbishop of Wiesstadt and Siegberg Conrad Clemens von August was detained by revolutionary forces being locked in the wine cellar of Wiesstadt cathedral removing the last prominent anti-republican voice within the city confirming the rapid takeover of the city by revolutionary elements.

Establishment of a revolutionary government

By noon on the 28th notable radicals and republicans had converged on the Weißenhaus to meet with the military revolutionary committee. This included Der Herold journalists Niels Uebelhoer and Alexander Neumayer, Artur Schönfeld and Ludwig Vollmar. Mayor Krieger who had been detained was pressured to either accept the authority of the revolutionary committee or resign - realising the increasingly radical direction of the revolutionary committee would inevitably lead to conflict with the central government Krieger officially resigned from his post handing power to Vogelstein as head of the city garrison, who subsequently turned over the city responsibilities to the revolutionary committee. For all intents and purposes the revolutionary committee was now the de facto and de jure government.

Fischart, who had been recovering from a hangover in the initial hours of the revolution, soon assembled a crowd in the Rudolfplatz in the east side of the city where he called for the resignation of the revolutionary committee and the formation of a new republican government that would replace the de facto deposed Cislanian provincial administration. Fischart called on the revolutionaries to support the ordinances of the revolutionary committee lionising Vogelstein as a "model Weranian, committed to the people rather then the king". Considered an excellent orator and propagandist Fischart's strong approval won over many republicans and socialists who distrusted the revolutionary committee due to its leaders being military officers who had served in the monarchist armies and had displayed no obvious republican leanings.

With the revolutionaries having concentrated power in the Weißenhaus revolutionary militia's had dispersed throughout the city to seize control of district councils. Local workers councils soon declared their loyalty to the revolutionary committee which was urged to formulate a more permanent governmental structure. The workers' and soldiers councils overwhelmingly supported the notion of installing Fischart as head of state of a revolutionary government and urged Vogelstein and Gottlieb to declare a dictatorship of the proletariat under Fischart's rule.

Fischart alongside a handful of his supporters met in the Weißenhaus with Vogelstein and Gottlieb where in became clear that despite his popularity Fischart had little appetite to govern as a dictator, claiming he would only take the role if the revolutionary government mobilised the garrison to instantly begin a march on the capital. Fischart predicted that the immediate mobilisation of a republican army would be able to trigger a wave of defections similar to what occurred in Bonnlitz during the Septemberist Revolt in 1836 and that if the revolutionaries dithered they would lose momentum. However recognising his scant support within military circles Fischart implored Vogelstein and Gottlieb to order the general mobilisation to put his plan into action.