Civil-Military State: Difference between revisions

(→Turfan) |

|||

| (23 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

== Origins == | == Origins == | ||

{{Main|Union of Khazestan and Pardaran}} {{See also|Zorasani Unification}} | |||

The history of Zorasan including the period of [[Zorasani unification]] (1948-1980), through its predecessor state, the [[Union of Khazestan and Pardaran]], saw the military play the most prominent role in state-building and governance post-independence. The UKP was governed as a single-party state under the military, which organised and led the sole legal political entity. The UKP’s extreme {{wp|militarism}} and the establishment of a collective {{wp|cult of personality}} around the institution would be maintained post-1980 for a period of ten years. | The history of Zorasan including the period of [[Zorasani unification]] (1948-1980), through its predecessor state, the [[Union of Khazestan and Pardaran]], saw the military play the most prominent role in state-building and governance post-independence. The UKP was governed as a single-party state under the military, which organised and led the sole legal political entity. The UKP’s extreme {{wp|militarism}} and the establishment of a collective {{wp|cult of personality}} around the institution would be maintained post-1980 for a period of ten years. | ||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

=== Adoption === | === Adoption === | ||

{{Main|2006 Zorasani constitutional referendum}} | |||

The official campaign for the referendum began on the 1 March, thought notably the campaign for those against the new constitution, though registered with the Union Electoral Commission, failed to materialise, with many of those most able to lead it either in prison or missing, the pro-military camp led by State President Alizadeh competed against no meaningful opposition. The Zorasani press, which had been decimated in the aftermath of the election through military raids and the closure of hundreds of left-leaning outlets, meant that the media sector was near unanimous in support of the new constitution. | The official campaign for the referendum began on the 1 March, thought notably the campaign for those against the new constitution, though registered with the Union Electoral Commission, failed to materialise, with many of those most able to lead it either in prison or missing, the pro-military camp led by State President Alizadeh competed against no meaningful opposition. The Zorasani press, which had been decimated in the aftermath of the election through military raids and the closure of hundreds of left-leaning outlets, meant that the media sector was near unanimous in support of the new constitution. | ||

On 10 July, the referendum passed with 88% of the popular vote, though turnout was only an estimated 60%. Throughout the campaign, Alizadeh and his True Way allies repeatedly promised that the document would only be in force for a period of ten years, until the “economic damage wrought by the enemy from within could be repaired.” It would take force on 20 March 2008, the Zorasani new year, and ostensibly last until 2018. The constitution remains in force today. | On 10 July, the referendum passed with 88% of the popular vote, though turnout was only an estimated 60%. Throughout the campaign, Alizadeh and his True Way allies repeatedly promised that the document would only be in force for a period of ten years, until the “economic damage wrought by the enemy from within could be repaired.” It would take force on 20 March 2008, the Zorasani new year, and ostensibly last until 2018. The constitution remains in force today. | ||

== Civil-Military State Theory == | |||

In the years leading to its adoption, the Civil-Military System was subject to various analyses and explanatory works, mostly in response to repeated claims it was simple power-grab by the military in wake of the [[Turfan]], dressed up as a major peaceful constitutional revolution toward a new stability inducing political structure. | |||

In a televised speech to army cadets, the then brigadier general [[Ashavazdar Golzadari]] explained the system as a “restoration in this country of the [[Union Fathers]]’ wishes, to see our Union be a union between the worker, the cleric and the soldier. We abandoned that wish and it brought us to near ruin, by honouring the wish and uniting the three sectors of Zorasani civilisation, we will at last build a union-government that will provide the material, security and spiritual needs of the nation.” | |||

[[File:Central Command Council room.png|290px|thumb|left|The [[Central Command Council]], the top military body enjoys significant powers under the Civil-Military System.]] | |||

Other military figures described the theory as simply, “a system that provides the nation a means for its most trusted, revered and trusted institution to play a positive role. Be it moderating the elected government, aiding the electing government and anchoring the nation in our glorious martial past that birth our Union.” | |||

In the lead up to the 2006 referendum on the constitution, the conservative True Way government presented the new constitution as a “means to ensure the moderation of political parties and governments, with respect to the modernisation and reform processes. With the military’s watch, the Union can progress forward at a pace most sustainable and beneficial to the people.” | |||

And so while the military presented it as a realisation of the country’s founding fathers’ vision, the civilian elected government presented it as a stabilising development, repeatedly referencing the economic damage and social upheaval caused by the reformist governments prior. Following the constitutions formal adoption in 2008, and the steady seizure of the media by the state, Zorasani media began to propagandise the new political reality as a “restoration of Sattarism in our hearts and nation.” By 2010, the state media campaign designed to link the political system to the country’s revolutionary unification process escalated dramatically, with the message claiming that it was in fact the final step in unification, with State President Hamid Alizadeh proclaiming in his re-election speech that year, “what we have achieved in our Union is the realisation of the dream of our parents and grandparents, a Union of the Zorasani peoples and the union of the cleric, the worker and the soldier, in one harmonious state of prosperity, stability and harmony.” | |||

In 2012, one of the most regarded Zorasani political scientists, Masoud Mazarani wrote, “what quite possibly began as a military plot to ensure that never again would an elected government threaten their power and interests and welcomed by the conservative parties to sustain their incumbency of office, has evolved to become a declaration of faith in Sattarism. They believe that by introducing to Zorasan a constitutionally mandated political militarism, the fruits of the nation’s labours will only increase.” | |||

== The state == | == The state == | ||

The Second Instrument of Union, Zorasan’s constitution was defined in a separate document produced by the [[Supreme Constitutional Committee]] in 2006. The “Delineation of the Civil-Military State Apparatus” sought to explain the powers and responsibilities handed to the military, and then mandating the elected government’s relationship to those afforded powers. | The Second Instrument of Union, Zorasan’s constitution was defined in a separate document produced by the [[Supreme Constitutional Committee]] in 2006. The “Delineation of the Civil-Military State Apparatus” sought to explain the powers and responsibilities handed to the military, and then mandating the elected government’s relationship to those afforded powers. Under the Second Instrument of Union, the [[Zorasani Irfanic Revolutionary Army]] was granted expansive powers and a formalised role within the state beyond its traditional provision of defence and power projection. | ||

=== Military === | ==== Executive ==== | ||

{{Main|Central Command Council}} | |||

The most notably provision was the establishment of the [[Central Command Council]], the most senior body of the armed forces, as part of the executive branch, yet independent of the elected government. This situation though on paper is meant to ensure the military only involves itself in matters defined in the Second Instrument of Union (defence, foreign policy and internal security), in reality, the Central Command Council has been known to exert its influence over social and economic affairs. Since 2008, the CCC has repeatedly stated that it would involve itself in all areas of government to ensure "moderation in reform", while not explicitly opposing any reforms. It has been known to champion certain reforms, including further pro-market reforms to the economy, social welfare, women's rights and has even led the elected government into reforms aimed at championing innovation and entrepreneurialism. | |||

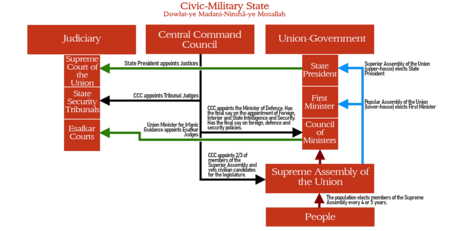

[[File:Zorasan Govt Diagram.png|450px|thumb|right|A diagram describing the Civil-Military State.]] | |||

The powers involving the executive branch afforded to the CCC are: | |||

* Provide advice and the final policy confirmation for matters relating to foreign, security, defence and internal security. | |||

* Approve or veto government policies relating to foreign relations, internal security and national defence. | |||

* Confirm or reject the First Minister’s appointments for the Union Ministries of Foreign Affairs, Internal Affairs and Justice. | |||

** Appoint the Union Minister for National Defence; nominally the [[Central Command Council|Chairman of the Central Command Council]], who also always concurrently serves as {{wp|commander-in-chief}} of the [[Zorasani Irfanic Revolutionary Army]]. | |||

* The military posseses the "Emergency Intervention Mechanism" within the constitution, which permits the Central Command Council to assume the full duties of the executive in the event of a national emergency or during war time. This would subordinate the [[Council of Union Ministers (Zorasan)|Council of Union Ministers]] to the CCC, which would constitute the head of government collectively. | |||

* The military's [[General Intelligence Service (Zorasan)|General Intelligence Service]] is granted the remit to operate domestically and may conduct operations relating to internal state security. | |||

* The military operates the [[Hasadar|Hasadar prison system]]. | |||

* The military's [[State Commission for Societal Defence]]'s remit and jurisidiction is extended nationally and beyond the armed forces. The SCSD is taksed with organising and managing the various patriotic grass-roots groups and organisations, the largest and most successful being the Wolves Organisation. The SCSD also serves as an anti-corruption task force, the official state censor and maintains the national telephone helpline for citizens to report "subversive behaviour." | |||

* The [[State Commission for Public Services]] is tasked with overseeing the civil service at the federal and state level. Its primary duty is to ensure the effecient implementation of government policies, but also to ensure the "patriotic service" of civil servants. This body is unique in that is managed equally by the CCC and civilian government. | |||

* The military is tasked with running the [[State Commission for All Media, Radio and Television]], the country's media regulator and censor. | |||

==== Legislative ==== | |||

The military's powers defined in the Second Instrument of Union in relation to the legislative branch are expansive and provide it with its dominating position within the political process. Owing to the liberal-reformist supermajorities seen in the 1990-2005 period, the Second Instrument was designed to deny any elected government the means to force through legislation that would "jeopardise the social and economic stability of the Union." This done by handing two-thirds of seats in the Superior Assembly of the Union (the upper-chamber) to the military’s political group, [[Zorasan Zendebad]]. These seats are held by officers appointed by the [[Central Command Council]] and are held for a single ten-year term. Among the 2/3rd members are {{wp|life-term|life-members}}, who are awarded these seats upon securing the rank of {{wp|general}} or its equivalent in other branches. As a further consequence to the military's position in the upper chamber, the election of a [[State President of the Union|State President]] (the {{wp|head of state}}), is dependent upon the candidates securing the backing of the military. This ensures that the head of state is both supportive of the military and compliant within the political framework. | |||

The military is also granted the right to appoint chairpersons to the joint legislative committees for foreign affairs, defence, internal affairs, law enforcement and intelligence. Specific to the defence and state security committees, the military possesses the right to withhold information or shut down meetings if inquiries breach areas of “national security that would endanger stability.” The military has been known to shut down committee meetings pertaining to human rights abuses by military agencies, while also utilising its appointed chairpersons to remove members who continue to push for investigations. | |||

One of the most controversial elements of the Civil-Military State is the military’s control of the [[Union Electoral Commission (Zorasan)|Union Electoral Commission]]. The Central Command Council is mandated to appoint the chair and deputy chair of the body which manages and organises all elections in the country; local, state and federal. The Union Electoral Commission is also mandated to vet candidates for public office at all three levels, enabling the military by extension to control those who are viable for public office. Nominally, the UEC vets candidates on the basis of criminal records, citizenship and their financial situation, however, the UEC also vets candidates on the basis of their public statements in regard to the Civil-Military State. In 2015 and 2019, the UEC blocked candidates who expressed criticism of the [[True Way]] government and particularly, First Minister [[Farzad Akbari]]. | |||

The | The most criticised point of the UEC is its right to invalidate elections, granting the military the power to invalidate the results of elections not seen to be in their interest. While the UEC has not invalidated any election since 2008, it did invalidate several constituency results of several prominent human rights activists who ran for office in 2015. The opposition press claimed this was work of the Central Command Council, who wished to avoid [[Shoreh Kadivar]], one of the most high-profile activists gaining a loudspeaker by virtue of being a member of parliament. In 2020, several opposition politicians revealed their fears that the UEC would invalidate a national election in the event of the [[True Way]] government being defeated. | ||

==== Judicial ==== | ==== Judicial ==== | ||

Ever since the establishment of the Union in 1980, the country’s judicial system has been divided into three distinct districts – Civil (constitutional, civil and criminal courts), Esafkar (Irfanic religious law courts) and State Security (matters relating specifically to terrorism, sedition etc). However, between 1980 and 2008, the State Security Tribunals fell out of use as the country both stabilised and successive governments sought to utilise the more accountable civil courts for cases. | |||

The 2008 constitution however, restored the Tribunals to prominence and handed responsibility of their running and administration to the military, furthermore, the State Security Justices would be appointed by the [[Central Command Council]]. In matters relating to national security and their corresponding laws, the Tribunals would take precedence over the civil courts, meaning any and all future charges of terrorism, sedition, treason or any violation of national security would be prosecuted before the Tribunals. The State Security Prosecution Service would also be able to lodge charges independently of the wider Federal Prosecution Office. The State Security Tribunals since 2008 has been utilised to prosecute charges against a variety of figures, including sitting members of parliament, business people and critics of the civil-military system. Notably, in the lead up to the 2019 election, over 30 members of centre-left and left-wing parties were brought before the Tribunal for “crimes against the Union.” | |||

== In practice == | == In practice == | ||

Since the adoption of the 2008 Constitution, the system of government has sparked a fierce debate as to whether in practice it protects or undermines Zorasan’s parliamentary democracy. In the 13 years since its adoption, the growing consensus has been that the civil-military system has produced in the country, a unique {{wp|constitutionalism|constitutional}} {{wp|Military dictatorship|military regime}}, in which the military, behind a vast bureaucratic network is the ultimate political authority yet constrained by constitutional limits. A secondary consensus has emerged that the system has promoted a restoration of authoritarian rule, with serious breaches of human rights and civil liberties by the military with the civil-elected government’s support or acquiescence. | |||

Masoud Mazarani, a prominent political scientist wrote in 2014, “the entire system is fuelled by the fraternal love between the military and the Zorasani right, which has been in government since 2005. The system is mutually beneficial, as it empowers the military once more, and enables the Right to remain in office, through the military’s use of their powers to preserve a compliant government.” | |||

Sharieh Khodapavar for her part in 2016 wrote, “to many Zorasanis the system is one that has provided stability, in comparison to the chaotic years of the reformist governments (1990-2005), while it has also provided increasing incomes, improved standards of living, sustain economic growth and better services. Conversely, to many, the system still provides them with the democratic outlet, while it is hard to see how the military impedes government when looking at the legislative process, it provides and protects and that fuels acceptance or at least resignation to the new normal.” | |||

=== Constitutional military regime === | === Constitutional military regime === | ||

The interpretation of the civil-military system as a “constitutional military regime” has grown in popularity among commentators since 2008. [[Estmere|Richard Fontaine]] wrote in 2011, “what we see in Zorasan bares the hallmarks of all military governments of history, statism, militarism, a supine civilian political structure, backed by draconian secret police actions, but with a functioning, if controlled and flawed democratic process.” The provisions within the 2008 constitution, which delineate the limits of the military’s role within government has been mostly observed, lending further credence to the description of military constitutionalism. The [[Supreme Constitutional Court of the Union]], has been successful in curtailing military excesses of its remits and powers since 2008, while studies have shown that the military has been active in observing its constitutional duties. Conversely, the Zorasani elected government has been successful in observing its constitutional limits in relation to the military. | |||

The democratic processes conducted in Zorasan have been repeatedly criticised by international bodies, governments and NGOs as “flawed and managed” toward the goal of “electing a government that would neither jeopardise the system or attempt to compete with the military once in office for power.” Several NGOs have cited the military’s overwhelming control over the nation’s press and the near blatant bias of these outlets toward the right-wing [[True Way]] electoral bloc. The military has also timely intervened, detaining opposition MPs and figures who pose the greatest challenge to the True Way. | |||

The system’s prolonging of conservative rule has led to a case of {{wp|state capture}} of key institutions by True Way. In the immediate aftermath of the [[Turfan]], thousands of civil servants were purged from their positions and replaced with conservative aligned employees. The most senior civil servants in permanent positions were replaced with True Way party elites. The military’s seizure of the media by both direct and indirect means has also led to a narrowing of debate within the media, to the extent that almost 90% of outlets produce pro-government, pro-military messages. At the 2010, 2015 and 2019 elections, the media was accused of bias and denying airtime to opposition parties, while the military-owned media group repeatedly spread misinformation and conspiracy theories about key opposition individuals and their parties. In all three elections, True Way was returned to office in landslides, though NGOs reported that the counting process was “incident free.” The relationship between the military and True Way specifically has been described as “blurring the lines between the military and state”, with several retired officers running and winning parliamentary seats for the party in the 2019 election. The close coordination of the military and True Way governments has led to some commentators to describe Zorasan as a {{wp|dominant party state}}, and others have gone further to describe it as a {{wp|single-party state}} in all but name. Virtually all commentators agree that the likliehood of True Way or any other major right-wing party or group seeking to undermine the system is virtually nil, enabling the military to full exercise its powers and dominant position. | |||

Those who argue that Zorasan is a constitutional military regime have also cited to the socio-cultural effects of the 2008 constitution. In a study on {{wp|militarism}} by the [[Caldia|University of Garrafrauns]], it was found that Zorasani society ranks as one of the most militarised in the world. Culturally speaking, veneration of the military (propagated by the media and education) has reached near religious levels, with individual soldiers treated as “saintly beings” and the members of the [[Central Command Council]], approached as “{{wp|demi-gods}}” in the state media. The traditions of the military are treated as traditions of the nation, while the values instilled in the soldiery is also instilled in school-age children, principally, “obedience, discipline, collectivism (being an integral piece of a larger machine) and nationalism.” State media and the education system celebrate the military through fixed annual events, such as “Defend the Union Day”, in which soldiers visit schools and host events or lead military style training. | |||

In 2019, the University of Garrafrauns studied Zorasani media productions, television series and feature length movies and reported 55% of productions involve a military plot or sub-plot. [[Pâyiz-dan Pâyiz]] (Autumn to Autumn), Zorasan’s longest running {{wp|soap opera}}, has six main characters who are active serving military members, and the soap which is watched by an estimated 13m people weekly pushes pro-military messaging through its episodes. The UG also studied {{wp|propaganda}}, including the usage of billboards, radio and televised commercials and found that the military would be spending an estimated €200 million a year on advertising. These are usually conflating the national interest with that of the military, or promoting the military as the “ultimate manifestation of the Union’s progress.” | |||

=== Authoritarianism === | === Authoritarianism === | ||

{{Main|Human rights in Zorasan}} | |||

One of the most profound consequence of the 2008 constitution and adoption of the Civil-Military System, was the systematic increase in human rights abuses and authoritarian governance. In wake of the 2005 union election, in which the right-wing conservative True Way alliance won in a landslide, they passed a series of security laws aimed at “re-stabilising the country and resuming economic development.” These laws would go on to form the legal basis for many abuses since. | |||

The 2005 Security Laws passed within the first 100 days of the True Way government restored {{wp|capital punishment}} for various crimes previously under its remit. This includes {{wp|sedition}}, {{wp|drug dealing}}, {{wp|smuggling}} and {{wp|separatism}}. {{wp|Torture}} was legalised under the title of “extreme interrogation processes”, while {{wp|detention without trial}} was restored, notably without any time limits. The same laws preceded the 2008 constitution by permitting domestic operations by the [[General Intelligence Service (Zorasan)|General Intelligence Service]] and the transfer of administration of the [[Hasadar system|Hasadar]] prison system to the military. The Hasadar prison system has been widely condemned by human rights activists since its first established in 1953, where prisoners are subject to {{wp|hard labour}}, {{wp|torture}}, {{wp|starvation}}, {{wp|emotional abuse|emotional}} and {{wp|psychological abuse|psychological}} abuse. | |||

{{wp|Forced disappearances}} are a common feature of life in Zorasan, where an estimated 1,200-1,500 people are disappeared annually, though a minority return after periods of time. The [[National Register of Subversive Subjects]], is a publicly accessible database of individuals who have been questioned or found guilty of various crimes against the state, the NRSS is used by private and state-owned companies to vet candidates for job positions, which has been condemned by NGOs to humiliate and deny opportunities for perceived enemies of the state. | |||

Mass surveillance and cyber-surveillance is also a permanent feature of the civil-military system and permitted under the constitution. There is an estimated 20.28 CCTV cameras every 100 individuals in Zorasan installed across the country, while select departments of the [[Union Ministry of State Intelligence and Security]] (MSIS) and the [[General Intelligence Service (Zorasan)|General Intelligence Service) (Akhidat), are dedicated solely to the surveillance of online activity of its citizens. | |||

[[Category:Zorasan]] | |||

Latest revision as of 15:56, 27 February 2021

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Zorasan |

The Civil-Military State (دولت شهری آرتشی; Dowlat-ye Šahri-e Arteši), also known by the neologism of Nezam (سیستم; lit. System), is a term used to describe the structure of government of the Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics. The term refers specifically to the system of government introduced with the 2008 Instrument of Union, the country’s constitution.

The system was devised and adopted for the purpose of providing stability in wake of the Turfan (2005-06), both in terms of society and the economy, which had been destabilised years prior by overzealous and poorly executed reforms under two successive liberal governments. By providing an constitutionally mandated space for the military within the central government, it was seen to provide a strong and popular check on the ambitions and agendas of the elected government.

Officially, the system delineates the powers and responsibilities afforded to the military and does so in the aim of fusing these together with the elected government, ostensibly to preserve the country’s multi-party parliamentary democracy. The system places the Central Command Council within, but independent of, the executive branch, and grants the military body significant influence over the judiciary and a dominating position within the legislative branch. These powers provide a separate check and balance on the elected government from within its own branch but through the other two, while this does achieve the stated goal of the system to restrain a reformist government, in reality it undermines the elected government and secures the Zorasani military as the true final arbiter of the political process.

Within Zorasan, the system divides opinion, generally along political party lines, with those of the centre-right and right-wing seeing it as a manifestation of the Union Fathers vision of a Union between the “Mazar, Barracks and Street”, and a guarantee of economic, political, and social stability, those of the centre and left see it as constructing an authoritarian, albeit constitutional military regime.

Origins

The history of Zorasan including the period of Zorasani unification (1948-1980), through its predecessor state, the Union of Khazestan and Pardaran, saw the military play the most prominent role in state-building and governance post-independence. The UKP was governed as a single-party state under the military, which organised and led the sole legal political entity. The UKP’s extreme militarism and the establishment of a collective cult of personality around the institution would be maintained post-1980 for a period of ten years.

The first five years of the UZIR’s existence, the military regime was retained, even if it did so to steadily prepare for democratic elections and a new constitution in 1985. The constitution adopted that year, while introducing a multi-party parliamentary democracy, provided the military certain rights and privileges, including it producing its own budget, retaining its vast business interests and exemptions from some laws. The military’s extensive media empire was vital in the continuation of the “army cult” (Arteš-ye Ferqe), this in turn secured the military as the most popular and trusted institution in the new state.

In 1990, the liberal-centre left Peace and Harmony Alliance won that year’s elections, sweeping into power Abdelraouf Wazzan as State President. Wazzan sought to modernise and expediate Zorasan’s economic and social liberalisation, however, he was cognisant of the military’s conservative nature and worked to co-opt the armed forces into supporting his reformist agenda. Between 1990 and 2000, the Wazzan government succeeded in doing so, mainly by avoiding the military’s business interests and media empire, he gained their support in expanding privatisation, softening the left-over policies of the Normalisation and promoting a more open and vibrant press. Wazzan also preserved the role of the Irfanic clerical establishment and the military’s role in society. His economic reforms though designed for long-term durations, succeeded in unleashing record breaking sustained economic growth and lifted an estimated 55 million people out of poverty.

In 2000, with Wazzan forced to leave office owed to term limits, he was succeeded by Ekrem Dalan, who’s National Reform Front had seized control of Peace and Harmony. Unlike Wazzan, Dalan was more identifiable as a neo-liberal and sought to expel the military entirely from government and society in the hope of establishing Zorasan as close to a modern liberal democracy as he could. This also involved his desires to secularise Zorasan and expel the Irfanic clergy from politics and governance. Ignoring calls for restraint from his predecessor and erstwhile mentor, Wazzan pursued his reforms with little to no regard to opposing opinion or input. By 2002, he had entered a fierce power-struggle with the military, with the latter aided and supported by conservative parties.

In 2002, a group of unnamed military officers produced a short book formulating a proposed “system of government, that would be built upon the single word: moderation.” This government would provide a constitutional role for the military in executive, legislative and judicial matters, while preserving popular democracy. The book caused a sensation among political commentators but had little effect on the wider population. However, the book would later re-emerge in 2005 as a progenitor for the Civil-Military System.

Turfan

In 2004, Dalan’s economic reforms and extensive, yet rapid privatisations of major state-owned enterprises sent shockwaves throughout Zorasan’s economy. Poorly executed reforms to the Zorasani General Petroleum Corporation (ZORGEN), disrupted oil and gas productions, fluctuating the global energy price. Dalan’s reforms prior to 2004 also served to fuel a meteoric rise in income inequalities, while the privatisation program sent over 1.2 million workers into unemployment in the space of a year. In response to attacks and criticisms from the Irfanic clergy, Dalan announced plans to ban clerics from being elected to public office, provoking a backlash from the conservative urban and rural poor. This anger and division led to the Sangar Incident, a foiled plot by mid-ranking army officers to stage a coup.

By 2005, the military owned media outlets began to attack the government and spread conspiracy theories. These outlets repeated claims that Dalan sought to sell ZORGEN to Euclean companies mobilised popular anger on the right, while the military’s own condemnations of inequality garnered the support of the urban and rural poor. Numerous nationalist and Sattarist societies, clubs and groups began to agitate against the government, demanding its resignation. To which Dalan rejected and insulted the unemployed in a series of gaffes.

In February 2005, mass protests erupted at several universities, where Sattarist student groups occupied campuses and conducted mock trials of academics who they accused of being neo-liberal sell outs. The student protests then escalated into a national protest movement, uniting the working and middle classes with the conservative parties, military, and clerics against Dalan’s government. The military repeated vowed not to intervene to restore civil order, while the police forces in Zorasan also showed restraint. Even as the protests began to torch businesses, institutions, and symbols of “Dalan’s upper-class”, the military’s media outlets continued to peddle conspiracy theories aimed at further fermenting unrest.

In June, the military for the first time lauded the idea of a new “civic-military state apparatus,” which saw welcoming and supportive rhetoric from right-wing parties. That month, Hamid Alizadeh, a right-wing neo-sattarist was elected candidate for state president for the True Way electoral group, which was immediately lavished with military support. In July, Dalan’s government was swept aside in a colossal True Way landslide, aided by the disappearance of over 60 MPs and candidates for Dalan’s Peace and Harmony alliance. Of the 60, 11 were reportedly assassinated or attacked by protesters, while the remaining 49 remain missing to this day.

On the first day of Alizadeh’s term, the military was deployed to cities across the country, restoring order with little to no resistance from the protest movements. The military media outlets began to focus their news stories on the potential of the new government.

Supreme Constitutional Committee

On 3 August 2005, Alizadeh announced the establishment of a Supreme Constitutional Committee, comprised of leading True Way figures and key individuals from the military. The task of the SCC was to devise a “temporary yet stabilising basic law that would restore Zorasan to the path of prosperity.” On the 4 August, Sadavir Hatami was appointed Chairman of the SCC. Hatami, a prominent general, was widely suspected of being one of the authors of the 2002 book that theorised a “civil-military state.”

By November that year, the SCC produced a preliminary outline of its proposed temporary constitution. In which it stated, “the basic premise of this temporary instrument of union, is that the military and elected government, as chosen by the people, would work hand-in-hand, concentrating on areas of respective expertise to provide stabilising good governance, with moderation and discipline in all matters.” During the immediate aftermath of the July elections, thousands of people were disappeared or arrested by the military’s General Intelligence Directorate. These included former politicians under the previous government, its supporters, as well as thousands of human rights activists, journalists, artists and academics.

On 1 January 2006, the SCC officially presented its completed document to the Popular Assembly of the Union. The document was well-received by the all-dominant True Way alliance and the centre-right parties. The centrist and left-wing opposition condemned the document as a return to military rule. On the 5 January, the Alizadeh government proposed a referendum on the new constitution to the Popular Assembly, to be held in July that year. The motion passed with only the left-wing parties voting against the referendum.

Adoption

The official campaign for the referendum began on the 1 March, thought notably the campaign for those against the new constitution, though registered with the Union Electoral Commission, failed to materialise, with many of those most able to lead it either in prison or missing, the pro-military camp led by State President Alizadeh competed against no meaningful opposition. The Zorasani press, which had been decimated in the aftermath of the election through military raids and the closure of hundreds of left-leaning outlets, meant that the media sector was near unanimous in support of the new constitution.

On 10 July, the referendum passed with 88% of the popular vote, though turnout was only an estimated 60%. Throughout the campaign, Alizadeh and his True Way allies repeatedly promised that the document would only be in force for a period of ten years, until the “economic damage wrought by the enemy from within could be repaired.” It would take force on 20 March 2008, the Zorasani new year, and ostensibly last until 2018. The constitution remains in force today.

Civil-Military State Theory

In the years leading to its adoption, the Civil-Military System was subject to various analyses and explanatory works, mostly in response to repeated claims it was simple power-grab by the military in wake of the Turfan, dressed up as a major peaceful constitutional revolution toward a new stability inducing political structure.

In a televised speech to army cadets, the then brigadier general Ashavazdar Golzadari explained the system as a “restoration in this country of the Union Fathers’ wishes, to see our Union be a union between the worker, the cleric and the soldier. We abandoned that wish and it brought us to near ruin, by honouring the wish and uniting the three sectors of Zorasani civilisation, we will at last build a union-government that will provide the material, security and spiritual needs of the nation.”

Other military figures described the theory as simply, “a system that provides the nation a means for its most trusted, revered and trusted institution to play a positive role. Be it moderating the elected government, aiding the electing government and anchoring the nation in our glorious martial past that birth our Union.”

In the lead up to the 2006 referendum on the constitution, the conservative True Way government presented the new constitution as a “means to ensure the moderation of political parties and governments, with respect to the modernisation and reform processes. With the military’s watch, the Union can progress forward at a pace most sustainable and beneficial to the people.”

And so while the military presented it as a realisation of the country’s founding fathers’ vision, the civilian elected government presented it as a stabilising development, repeatedly referencing the economic damage and social upheaval caused by the reformist governments prior. Following the constitutions formal adoption in 2008, and the steady seizure of the media by the state, Zorasani media began to propagandise the new political reality as a “restoration of Sattarism in our hearts and nation.” By 2010, the state media campaign designed to link the political system to the country’s revolutionary unification process escalated dramatically, with the message claiming that it was in fact the final step in unification, with State President Hamid Alizadeh proclaiming in his re-election speech that year, “what we have achieved in our Union is the realisation of the dream of our parents and grandparents, a Union of the Zorasani peoples and the union of the cleric, the worker and the soldier, in one harmonious state of prosperity, stability and harmony.”

In 2012, one of the most regarded Zorasani political scientists, Masoud Mazarani wrote, “what quite possibly began as a military plot to ensure that never again would an elected government threaten their power and interests and welcomed by the conservative parties to sustain their incumbency of office, has evolved to become a declaration of faith in Sattarism. They believe that by introducing to Zorasan a constitutionally mandated political militarism, the fruits of the nation’s labours will only increase.”

The state

The Second Instrument of Union, Zorasan’s constitution was defined in a separate document produced by the Supreme Constitutional Committee in 2006. The “Delineation of the Civil-Military State Apparatus” sought to explain the powers and responsibilities handed to the military, and then mandating the elected government’s relationship to those afforded powers. Under the Second Instrument of Union, the Zorasani Irfanic Revolutionary Army was granted expansive powers and a formalised role within the state beyond its traditional provision of defence and power projection.

Executive

The most notably provision was the establishment of the Central Command Council, the most senior body of the armed forces, as part of the executive branch, yet independent of the elected government. This situation though on paper is meant to ensure the military only involves itself in matters defined in the Second Instrument of Union (defence, foreign policy and internal security), in reality, the Central Command Council has been known to exert its influence over social and economic affairs. Since 2008, the CCC has repeatedly stated that it would involve itself in all areas of government to ensure "moderation in reform", while not explicitly opposing any reforms. It has been known to champion certain reforms, including further pro-market reforms to the economy, social welfare, women's rights and has even led the elected government into reforms aimed at championing innovation and entrepreneurialism.

The powers involving the executive branch afforded to the CCC are:

- Provide advice and the final policy confirmation for matters relating to foreign, security, defence and internal security.

- Approve or veto government policies relating to foreign relations, internal security and national defence.

- Confirm or reject the First Minister’s appointments for the Union Ministries of Foreign Affairs, Internal Affairs and Justice.

- Appoint the Union Minister for National Defence; nominally the Chairman of the Central Command Council, who also always concurrently serves as commander-in-chief of the Zorasani Irfanic Revolutionary Army.

- The military posseses the "Emergency Intervention Mechanism" within the constitution, which permits the Central Command Council to assume the full duties of the executive in the event of a national emergency or during war time. This would subordinate the Council of Union Ministers to the CCC, which would constitute the head of government collectively.

- The military's General Intelligence Service is granted the remit to operate domestically and may conduct operations relating to internal state security.

- The military operates the Hasadar prison system.

- The military's State Commission for Societal Defence's remit and jurisidiction is extended nationally and beyond the armed forces. The SCSD is taksed with organising and managing the various patriotic grass-roots groups and organisations, the largest and most successful being the Wolves Organisation. The SCSD also serves as an anti-corruption task force, the official state censor and maintains the national telephone helpline for citizens to report "subversive behaviour."

- The State Commission for Public Services is tasked with overseeing the civil service at the federal and state level. Its primary duty is to ensure the effecient implementation of government policies, but also to ensure the "patriotic service" of civil servants. This body is unique in that is managed equally by the CCC and civilian government.

- The military is tasked with running the State Commission for All Media, Radio and Television, the country's media regulator and censor.

Legislative

The military's powers defined in the Second Instrument of Union in relation to the legislative branch are expansive and provide it with its dominating position within the political process. Owing to the liberal-reformist supermajorities seen in the 1990-2005 period, the Second Instrument was designed to deny any elected government the means to force through legislation that would "jeopardise the social and economic stability of the Union." This done by handing two-thirds of seats in the Superior Assembly of the Union (the upper-chamber) to the military’s political group, Zorasan Zendebad. These seats are held by officers appointed by the Central Command Council and are held for a single ten-year term. Among the 2/3rd members are life-members, who are awarded these seats upon securing the rank of general or its equivalent in other branches. As a further consequence to the military's position in the upper chamber, the election of a State President (the head of state), is dependent upon the candidates securing the backing of the military. This ensures that the head of state is both supportive of the military and compliant within the political framework.

The military is also granted the right to appoint chairpersons to the joint legislative committees for foreign affairs, defence, internal affairs, law enforcement and intelligence. Specific to the defence and state security committees, the military possesses the right to withhold information or shut down meetings if inquiries breach areas of “national security that would endanger stability.” The military has been known to shut down committee meetings pertaining to human rights abuses by military agencies, while also utilising its appointed chairpersons to remove members who continue to push for investigations.

One of the most controversial elements of the Civil-Military State is the military’s control of the Union Electoral Commission. The Central Command Council is mandated to appoint the chair and deputy chair of the body which manages and organises all elections in the country; local, state and federal. The Union Electoral Commission is also mandated to vet candidates for public office at all three levels, enabling the military by extension to control those who are viable for public office. Nominally, the UEC vets candidates on the basis of criminal records, citizenship and their financial situation, however, the UEC also vets candidates on the basis of their public statements in regard to the Civil-Military State. In 2015 and 2019, the UEC blocked candidates who expressed criticism of the True Way government and particularly, First Minister Farzad Akbari.

The most criticised point of the UEC is its right to invalidate elections, granting the military the power to invalidate the results of elections not seen to be in their interest. While the UEC has not invalidated any election since 2008, it did invalidate several constituency results of several prominent human rights activists who ran for office in 2015. The opposition press claimed this was work of the Central Command Council, who wished to avoid Shoreh Kadivar, one of the most high-profile activists gaining a loudspeaker by virtue of being a member of parliament. In 2020, several opposition politicians revealed their fears that the UEC would invalidate a national election in the event of the True Way government being defeated.

Judicial

Ever since the establishment of the Union in 1980, the country’s judicial system has been divided into three distinct districts – Civil (constitutional, civil and criminal courts), Esafkar (Irfanic religious law courts) and State Security (matters relating specifically to terrorism, sedition etc). However, between 1980 and 2008, the State Security Tribunals fell out of use as the country both stabilised and successive governments sought to utilise the more accountable civil courts for cases.

The 2008 constitution however, restored the Tribunals to prominence and handed responsibility of their running and administration to the military, furthermore, the State Security Justices would be appointed by the Central Command Council. In matters relating to national security and their corresponding laws, the Tribunals would take precedence over the civil courts, meaning any and all future charges of terrorism, sedition, treason or any violation of national security would be prosecuted before the Tribunals. The State Security Prosecution Service would also be able to lodge charges independently of the wider Federal Prosecution Office. The State Security Tribunals since 2008 has been utilised to prosecute charges against a variety of figures, including sitting members of parliament, business people and critics of the civil-military system. Notably, in the lead up to the 2019 election, over 30 members of centre-left and left-wing parties were brought before the Tribunal for “crimes against the Union.”

In practice

Since the adoption of the 2008 Constitution, the system of government has sparked a fierce debate as to whether in practice it protects or undermines Zorasan’s parliamentary democracy. In the 13 years since its adoption, the growing consensus has been that the civil-military system has produced in the country, a unique constitutional military regime, in which the military, behind a vast bureaucratic network is the ultimate political authority yet constrained by constitutional limits. A secondary consensus has emerged that the system has promoted a restoration of authoritarian rule, with serious breaches of human rights and civil liberties by the military with the civil-elected government’s support or acquiescence.

Masoud Mazarani, a prominent political scientist wrote in 2014, “the entire system is fuelled by the fraternal love between the military and the Zorasani right, which has been in government since 2005. The system is mutually beneficial, as it empowers the military once more, and enables the Right to remain in office, through the military’s use of their powers to preserve a compliant government.”

Sharieh Khodapavar for her part in 2016 wrote, “to many Zorasanis the system is one that has provided stability, in comparison to the chaotic years of the reformist governments (1990-2005), while it has also provided increasing incomes, improved standards of living, sustain economic growth and better services. Conversely, to many, the system still provides them with the democratic outlet, while it is hard to see how the military impedes government when looking at the legislative process, it provides and protects and that fuels acceptance or at least resignation to the new normal.”

Constitutional military regime

The interpretation of the civil-military system as a “constitutional military regime” has grown in popularity among commentators since 2008. Richard Fontaine wrote in 2011, “what we see in Zorasan bares the hallmarks of all military governments of history, statism, militarism, a supine civilian political structure, backed by draconian secret police actions, but with a functioning, if controlled and flawed democratic process.” The provisions within the 2008 constitution, which delineate the limits of the military’s role within government has been mostly observed, lending further credence to the description of military constitutionalism. The Supreme Constitutional Court of the Union, has been successful in curtailing military excesses of its remits and powers since 2008, while studies have shown that the military has been active in observing its constitutional duties. Conversely, the Zorasani elected government has been successful in observing its constitutional limits in relation to the military.

The democratic processes conducted in Zorasan have been repeatedly criticised by international bodies, governments and NGOs as “flawed and managed” toward the goal of “electing a government that would neither jeopardise the system or attempt to compete with the military once in office for power.” Several NGOs have cited the military’s overwhelming control over the nation’s press and the near blatant bias of these outlets toward the right-wing True Way electoral bloc. The military has also timely intervened, detaining opposition MPs and figures who pose the greatest challenge to the True Way.

The system’s prolonging of conservative rule has led to a case of state capture of key institutions by True Way. In the immediate aftermath of the Turfan, thousands of civil servants were purged from their positions and replaced with conservative aligned employees. The most senior civil servants in permanent positions were replaced with True Way party elites. The military’s seizure of the media by both direct and indirect means has also led to a narrowing of debate within the media, to the extent that almost 90% of outlets produce pro-government, pro-military messages. At the 2010, 2015 and 2019 elections, the media was accused of bias and denying airtime to opposition parties, while the military-owned media group repeatedly spread misinformation and conspiracy theories about key opposition individuals and their parties. In all three elections, True Way was returned to office in landslides, though NGOs reported that the counting process was “incident free.” The relationship between the military and True Way specifically has been described as “blurring the lines between the military and state”, with several retired officers running and winning parliamentary seats for the party in the 2019 election. The close coordination of the military and True Way governments has led to some commentators to describe Zorasan as a dominant party state, and others have gone further to describe it as a single-party state in all but name. Virtually all commentators agree that the likliehood of True Way or any other major right-wing party or group seeking to undermine the system is virtually nil, enabling the military to full exercise its powers and dominant position.

Those who argue that Zorasan is a constitutional military regime have also cited to the socio-cultural effects of the 2008 constitution. In a study on militarism by the University of Garrafrauns, it was found that Zorasani society ranks as one of the most militarised in the world. Culturally speaking, veneration of the military (propagated by the media and education) has reached near religious levels, with individual soldiers treated as “saintly beings” and the members of the Central Command Council, approached as “demi-gods” in the state media. The traditions of the military are treated as traditions of the nation, while the values instilled in the soldiery is also instilled in school-age children, principally, “obedience, discipline, collectivism (being an integral piece of a larger machine) and nationalism.” State media and the education system celebrate the military through fixed annual events, such as “Defend the Union Day”, in which soldiers visit schools and host events or lead military style training.

In 2019, the University of Garrafrauns studied Zorasani media productions, television series and feature length movies and reported 55% of productions involve a military plot or sub-plot. Pâyiz-dan Pâyiz (Autumn to Autumn), Zorasan’s longest running soap opera, has six main characters who are active serving military members, and the soap which is watched by an estimated 13m people weekly pushes pro-military messaging through its episodes. The UG also studied propaganda, including the usage of billboards, radio and televised commercials and found that the military would be spending an estimated €200 million a year on advertising. These are usually conflating the national interest with that of the military, or promoting the military as the “ultimate manifestation of the Union’s progress.”

Authoritarianism

One of the most profound consequence of the 2008 constitution and adoption of the Civil-Military System, was the systematic increase in human rights abuses and authoritarian governance. In wake of the 2005 union election, in which the right-wing conservative True Way alliance won in a landslide, they passed a series of security laws aimed at “re-stabilising the country and resuming economic development.” These laws would go on to form the legal basis for many abuses since.

The 2005 Security Laws passed within the first 100 days of the True Way government restored capital punishment for various crimes previously under its remit. This includes sedition, drug dealing, smuggling and separatism. Torture was legalised under the title of “extreme interrogation processes”, while detention without trial was restored, notably without any time limits. The same laws preceded the 2008 constitution by permitting domestic operations by the General Intelligence Service and the transfer of administration of the Hasadar prison system to the military. The Hasadar prison system has been widely condemned by human rights activists since its first established in 1953, where prisoners are subject to hard labour, torture, starvation, emotional and psychological abuse.

Forced disappearances are a common feature of life in Zorasan, where an estimated 1,200-1,500 people are disappeared annually, though a minority return after periods of time. The National Register of Subversive Subjects, is a publicly accessible database of individuals who have been questioned or found guilty of various crimes against the state, the NRSS is used by private and state-owned companies to vet candidates for job positions, which has been condemned by NGOs to humiliate and deny opportunities for perceived enemies of the state.

Mass surveillance and cyber-surveillance is also a permanent feature of the civil-military system and permitted under the constitution. There is an estimated 20.28 CCTV cameras every 100 individuals in Zorasan installed across the country, while select departments of the Union Ministry of State Intelligence and Security (MSIS) and the [[General Intelligence Service (Zorasan)|General Intelligence Service) (Akhidat), are dedicated solely to the surveillance of online activity of its citizens.