Etrurian First Republic: Difference between revisions

| (15 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

|s1 = United Kingdom of Etruria | |s1 = United Kingdom of Etruria | ||

|flag_s1 = Flag of the United Kingdom of Etruria.png | |flag_s1 = Flag of the United Kingdom of Etruria.png | ||

|s2 = | |s2 = Adamantina | ||

|flag_s2 = | |flag_s2 = Flag_of_Adamantina.svg | ||

|s3 = Gapolania | |s3 = Gapolania | ||

|flag_s3 = Gapolania flag.png | |flag_s3 = Gapolania flag.png | ||

| Line 217: | Line 217: | ||

* Introduction of the Nobilis Hospes (Noble Host) system of mass conscription. Purges of the officer corps of the Etrurian states is ended. | * Introduction of the Nobilis Hospes (Noble Host) system of mass conscription. Purges of the officer corps of the Etrurian states is ended. | ||

* TBD | * TBD | ||

=== Colonial unrest === | |||

=== Zenith === | === Zenith === | ||

| Line 222: | Line 223: | ||

=== Caltrini Restoration === | === Caltrini Restoration === | ||

== Government == | == Government == | ||

{{Main|Government of the Etrurian First Republic}} | |||

{{See also|Consistories of the Republic}} | |||

From 1784 to 1785, the Republic’s system of government was chaotic and poorly defined, with competition and administrative overlap between the Popular Convention and the Council of Nine, which formed a nascent collective executive and comprised of three members from three principal revolutionary factions. Vicious infighting and power struggles between the three factions would end in early 1785, with La Purga, the coup d’état launched by the Patheonisti. | From 1784 to 1785, the Republic’s system of government was chaotic and poorly defined, with competition and administrative overlap between the Popular Convention and the Council of Nine, which formed a nascent collective executive and comprised of three members from three principal revolutionary factions. Vicious infighting and power struggles between the three factions would end in early 1785, with La Purga, the coup d’état launched by the Patheonisti. | ||

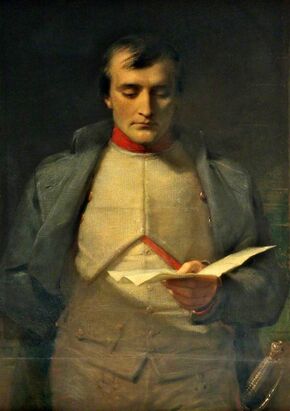

[[File:FrancescoCassioCaciarelli.jpg|290px|thumb|left|[[Francesco Cassio Caciarelli]] served as [[First Citizen of Etruria|First Citizen]] from 1785 to 1810 and exiled to [[Aeolia]] following the [[Caltrini Restoration]], he died a year later.]] | [[File:FrancescoCassioCaciarelli.jpg|290px|thumb|left|[[Francesco Cassio Caciarelli]] served as [[First Citizen of Etruria|First Citizen]] from 1785 to 1810 and exiled to [[Aeolia]] following the [[Caltrini Restoration]], he died a year later.]] | ||

[[File:Consilium.png|290px|thumb|right|The members of the Consilium from 1785 to 1810. Together, they formed the collective executive of the Republic and toward the end would exert total dominance over the political system.]] | [[File:Consilium.png|290px|thumb|right|The members of the Consilium from 1785 to 1810. Together, they formed the collective executive of the Republic and toward the end would exert total dominance over the political system. From top left-clockwise: [[Francesco Cassio Caciarelli]], [[Umberto Benedetto Scorsi]], [[Oliviero Giovanni Carafa]], [[Giovanni Battista Orsini]], [[Leopoldo Augustino Furfaro]], [[Giorlamo lodare-Dio Schiave]] and [[Giovanni Paolo Mancera]]]] | ||

Following their seizure of power and the Convention, the Pantheonisti, proclaimed the [[Devotion of the Republic to Heaven]] and forced through the Constitution of 1785, which had been written as early 1780. This constitution established the system of government that would remain in place near intact from its inception to the restoration of monarchy in 1810. [[Francesco Cassio Caciarelli]], who was the leader of the Pantheonisti served as [[First Citizen of Etruria|First Citizen]] for the entirety of the Republic's existence, his personal role and leadership has led to many to debate whether the Republic was dictatorship or a legitimate {{wp|directorial republic}}. | Following their seizure of power and the Convention, the Pantheonisti, proclaimed the [[Devotion of the Republic to Heaven]] and forced through the Constitution of 1785, which had been written as early 1780. This constitution established the system of government that would remain in place near intact from its inception to the restoration of monarchy in 1810. [[Francesco Cassio Caciarelli]], who was the leader of the Pantheonisti served as [[First Citizen of Etruria|First Citizen]] for the entirety of the Republic's existence, his personal role and leadership has led to many to debate whether the Republic was dictatorship or a legitimate {{wp|directorial republic}}. | ||

| Line 234: | Line 237: | ||

=== Democracy === | === Democracy === | ||

The First Republic introduced universal suffrage for men and women aged 21 and above in 1785, weeks after the La Purga. In the first major election of the Pantheonisti Domination, the revolutionary government put the [[Devotion of the Republic to Heaven]] to the people through a plebiscite. As the Tyrrhenian government pre-revolution lacked any certifiable record keeping of its own population, the government opted to utilise the Catholic Church as a means of organising democratic processes. As the churches across Tyrrhenus possessed maintained records of its congregants the Republic mandated that all votes be held on Sundays after Mass – this was further aided by the Senate Edict of the Liturgies which mandated church attendance. The Plebiscite was held on 10 April 1785 and saw just over 4.3 million votes cast across Tyrrenhus, with 88% of votes supporting the Devotion of the Republic. | |||

In practice this mass form of voting was the first within continental Euclea of its kind, though subject to abuse and questionable legitimacy. In the case of elections for the Senate of the Republic, candidates from the 300 constituencies would produce letters which were mass produced for every church in their constituency, this would then be read out by the parish priest. These letters served as campaign leaflets, with the candidates making their case for election. Once read, the priest would then ask the congregation to raise their hands for which candidate they supported, the results from each church would be collated and counted at the seat of the Archdiocese (the administrative divisions of the First Republic were established over the Archdioceses) and then revealed to the candidates. This would be repeated for plebiscites, though often in place of letters would be pamphlets produced by the Consilium with no counter arguments. | |||

Historians have long criticised the Pantheonisti’s approach to democracy, which more often than not relied upon parish priests to influence votes – documented cases by [[Matteo Giovanni Montecalvo]], one of the most reliable writers of the time, revealed that often priests would tell the congregants when to raise their hands, near exclusively in support of the Pantheonisti. However, democracy within the First Republic notably did not exclude women, nor between the propertied or peasant classes and by utilising a vote by hand, it removed any discrimination of the literate and illiterate. Other historians have viewed the use of Churches for the exercising of democracy as a secondary means of further wedding liberty, democracy and the republic to the Catholic faith. Francis George, a prominent historian on the 18th century revolutions wrote, “the Pantheonisti were masters of politics, by strongarming the dioceses into running their elections they truly wedded liberty and functions of the Republic to mass, to the {{wp|eucharist}} and the {{wp|liturgies}}, while also utilising an unparalleled organised network and structure of communal gathering.” | |||

During its 25-year existence, the First Republic held six parliamentary elections and four plebiscites, each resulting in a resounding victory for the Pantheonisti. | |||

=== Pantheonisti === | === Pantheonisti === | ||

{{Main|Pantheonisti}} | |||

Throughout the First Republic's existence, it was dominated at all levels by the [[Patheonisti|Society of the Servants of Christ and the Liberties]], though they were more commonly and popular known as the Pantheonisti (lit. Pantheonists), owing to the taverna they met at being beside the Pantheon of Sol Invictus in Tyrrenhus. The Pantheonisti were established in 1779 as a club for religious middle-class lawyers, merchants and academics. By 1782, it began to draw significant support from the city’s clergy and religious lay people. | |||

[[File:Pantheon Rom 1 cropped.jpg|290px|thumb|left|The Pantheonisti earned their popular name from the taverna they attended during the Revolution beside the Pantheon of Sol Invictus in Tyrrenhus.]] | |||

The Pantheonisti was a markedly united and cohesive faction, that was fiercely loyal to its “Charter of Universal Liberty and Salvation”, which was the modern equivalent of a political manifesto. The Charter detailed its principles (See the Canon of Heaven’s Devotions) and its plans, including the establishment of a “unitary, virtuous, Catholic and free republic.” Unlike its compatriots in the [[Amathian Empyreal Republic]], the Pantheonisti did afford a utopian end goal for its followers, but rather believed and championed the view of the “Heaven’s Republic shall be the chariot upon which we shall reach the Kingdom of God”, insofar that the Republic would provide a second redemption of mankind and erase the near heretical and sinful nature provided by monarchism. Though followings its decisive victories in the First and Second Wars of the League in the 1780s and the Capture of Solaria, the Pantheonisti sought to extend further its boundaries in hope of achieving [[Ecumenical Unification]], establishing a unified republic over all of Catholic Euclea and sister republics in the Episemalist west. | |||

At its height, the Pantheonisti boasted an estimated 500,000 members across what is modern Etruria, and boasted 40,000 within the [[Poor-Fellow Soldiers of Sotirias and the Republic]], originally a collection of Tyrrenhus’ urban poor who served as the “fist of the revolution” and were the primary instigators of La Purga on behalf of the Pantheonisti. The Poor-Fellows would later be deployed with the revolutionary armies. | |||

The Pantheonisti are widely considered be a bourgeois radical faction, owing to its leadership being drawn exclusively from the professional class together with the clergy. Though, Francis George remarked, “though thoroughly bourgeois, its agenda and belief system transcended class and wealth divisions in 18th century Etruria, its appeal was the promise of political and spiritual salvation, while its outward egalitarianism dissuaded mistrust by the peasant poor, uniting the two halves into a fierce and cohesive mass.” | |||

Following La Purga, the Pantheonisti held total control over the Senate, the Consistories and by the mid-1780s, total control over the absorbed officer corps. It ruthlessly punished and persecuted its rivals and enemies, justifying such and its wars as the “second cataclysm of Sodom and Gomorrah.” The Pantheonisti also relied heavily on mass hysteria to sustain its various [[Bonfire (Etruria)|Bonfires]] and [[La Tempesta|the Tempest]]. | |||

=== Canon of Heaven's Devotions === | === Canon of Heaven's Devotions === | ||

{{Main|Canon of Heaven's Devotions}} | {{Main|Canon of Heaven's Devotions}} | ||

| Line 277: | Line 301: | ||

|{{wp|Romans 13|Solarians 13:1-7}}: "Let everyone be subject to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except that which God has established. The authorities that exist have been established by God." | |{{wp|Romans 13|Solarians 13:1-7}}: "Let everyone be subject to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except that which God has established. The authorities that exist have been established by God." | ||

|While opponents of the Republic attempted to cite this chapter of Solarians in defence of monarchy, the Pantheonisti reacted by claiming that God would not call for obedience to rulers who sinned against him and abused his gift of authority. They claimed further that Solarians 13:1-7 would only be viable for virtuous and moral governments chosen by the people through the gift of free will. While this Devotion would later be abused by the Pantheonisti, modern historians read it as a call for the respect of democratic results and at worse, a justification for ultra-{{wp|majoritarianism}} or a more draconian interpretation of the {{wp|general will}}. | |While opponents of the Republic attempted to cite this chapter of Solarians in defence of monarchy, the Pantheonisti reacted by claiming that God would not call for obedience to rulers who sinned against him and abused his gift of authority. They claimed further that Solarians 13:1-7 would only be viable for virtuous and moral governments chosen by the people through the gift of free will. While this Devotion would later be abused by the Pantheonisti, modern historians read it as a call for the respect of democratic results and at worse, a justification for ultra-{{wp|majoritarianism}} or a more draconian interpretation of the {{wp|general will}}. | ||

|- | |||

|{{wp|Fraternity (philosophy)|Fraternity}} - Fraternitās | |||

|The belief that shared citizenship of the Republic as well as the {{Wp|Kingdom of God (Christianity)|Kingdom of Heaven}} afforded fraternity between peoples. This was generally speaking one of the more ecompassing Devotions, in which it covered equality of citizenship, nationalism and desires for the united Ecumene. It sought to consolidate society into singular cohesive unit bound by faith, liberty and patriotism. | |||

|{{wp|Matthew 5:5}}: "Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the Earth." | |||

|Matthew 5:5 was widely perceived at the time to be the ultimate rallying cry of the revolutionaries under the Patheonisti, and was interpreted in two significant ways. The first, was to proclaim the inevitable dominion of creation by the powerless and common people, "the huddled masses on the pews" and inevitable victory of the powerless as they unleashed their liberty through liberation from tyranny. The second interpretation was the unity the common people enjoy through their shared submission to tyranny and despots - "only through unity can the powerless and the meek inherit God's Earth in true liberty." | |||

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 286: | Line 315: | ||

== Revolutionary Armies == | == Revolutionary Armies == | ||

{{Main|Etrurian Revolutionary Army}} | |||

The armies of the Etrurian Republic, since referred to as the Etrurian Revolutionary Army, though at the time, officially named by the Pantheonisti as the “Army of the Republic and Holy Faith in Jesus Sotirias.” It was first founded out of the remains of the Tyrrhenian Royal Army immediately after the execution of [[Alessandro IV of Tyrrhenus|Grand Prince Alessandro IV]]. | |||

[[File:Etrurian Revolutionary Army.png|290px|thumb|left|The "Army of the Republic and Holy Faith in Jesus Sotirias" swiftly reformed and reorganised in 1786 after a year of catestrophic defeats and losses to become one of the most capable and largest armies in 18th century Euclea.]] | |||

Between 1784 and 1786, the initial revolutionary army was noted as being crippled by incompetence, disobedience and disorganisation. Many Tyrrhenian officers had either fled north to other Etrurian states or been imprisoned, exiled or executed by the Popular Convention. This was made apparent during the early stages of the [[War of the First League]], when the revolutionary army disintegrated in battle against the [[Unio Trium Nationum]] and the combined armies of the Duchies of Dinara and Peravia. These early defeats resulted in the [[Nobilis Hospises|Edict of the Nobilis Hospises]], which instituted general conscription and the establishment of a wartime economy. Together with the Edict, came a series of efforts to rehabilitate royalist Tyrrhenian officers held in prison, through public takings of the “Devotion Oath” and the deployment of Representatives of the Republic to every regiment, as well as reform of the officer corps, enabled the revolutionary army to reorganise and score key victories. | |||

The 1786 reforms enabled the revolutionary army to utilise the experience and discipline of royalist officers, while utilising the fervour and zealotry of the rank and file. While the revolutionary army was outnumbered 3:1 during the War of the First League, its fervour and commitment overwhelmed its enemies. As the Republic scored victories it would inevitably expand its borders, annexing Carinthia, Novalia, Carvagna and Torrazzia by 1788, before annexing Povelia without firing a shot the same year. By 1789, the entirety of modern Etruria, with the exception of the [[Ecclesiastical States (Kylaris)|Ecclesiastical States]] had fallen to the republic. In November 1789, the republic captured Solaria, ending the Ecclesiastical States and forcing the Papacy into exile in [[Gaullica]]. Eager to replenish its ranks, the republic expanded the jurisdiction of the Nobilis Hospises edict across Etruria, while also absorbing officer corps when viable. | |||

By the onset of the First War of the Grand Coalition, the republic was able to field an army of 1,200,000 soldiers, one of the largest in the world at that time. The republic throughout its various wars would suffer from continued shortages of cannon and horses, limiting its artillery and cavalry corps, though historians have long lauded the republic’s infantry for its discipline, organisation and fervour. That the republic was able to confront its enemies and score victories even when isolated and surrounded on three sides has also been lauded by historians. | |||

The initial revolutionary wars of the late 1780s, produced many of the generals who would go on to lead the republic to major victories in the 1790s against the Euclean monarchies. These included [[Giorlamo lodare-Dio Schiave]], [[Augustino Cesare Santoro]] and [[Caio Teme-Dio Trellini]]. However, the tide would turn in the early 1800s, with defeats at the hands of Gaullica, while the collapse of the [[Weranian Republic]] in northern Euclea, would enable the entry of [[Estmere]] and [[Soravia]] into the conflict against Etruria, which in turn soured public support for the republic and the eventual restoration of monarchy in 1810. | |||

=== Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Sotirias and the Republic === | |||

==Society== | ==Society== | ||

=== Religion === | === Religion === | ||

{{Main|Solarian Catholicism and the Etrurian Revolution}} | |||

=== Virtus === | === Virtus === | ||

=== Nationalism === | === Nationalism === | ||

=== Canon of Heaven's Devotions === | === Canon of Heaven's Devotions === | ||

== Etrurian colonies == | == Etrurian colonies == | ||

=== Gapolonia === | |||

=== Adamantina === | |||

== Legacy == | == Legacy == | ||

Latest revision as of 22:49, 27 November 2022

Etrurian Republic Republic of Heaven Reppublica Etruriana Repubblica del Cielo | |

|---|---|

Motto:

| |

Anthem:

| |

| Capital | Tyrrenhus (1784-1787) Solaria (1787-1810) |

| Religion | Solarian Catholicism |

| Demonym(s) | Etrurian |

| Government | Directorial republic (1784-1785) Theo-directorial republic (1785-1810) |

| President of the Convention | |

• 1784 | Aurelio Polizzi |

| Member of the Aventine Triad | |

• 1784-1785 | Francesco Cassio Caciarelli |

• 1784-1785 | Massimiliano Malaspina |

• 1784-1785 | Giovanni-Paolo Danova |

| First Citizen | |

• 1785-1810 | Francesco Cassio Caciarelli |

| Legislature | Senate of the Republic |

| History | |

• Established | 20 January 1784 |

| 9 September 1783 | |

| 3 November 1783 | |

| 20 January 1784 | |

| 10 July 1784 | |

• La Purga | 18 July 1784 |

| 20 July 1784 | |

| 12 August 1810 | |

| Population | |

• 1784 | 18,398,200 |

• 1810 | 19,998,200 |

| Currency | Etrurian piastra |

| Today part of | Etruria Gaullica Piraea Galenia |

The Etrurian First Republic (Prima Repubblica Etruriana), officially known as the Etrurian Republic (Repubblica Etruriana) and co-officially known as the Republic of Heaven (Repubblica del Cielo), was founded on 20 September 1784, during the Etrurian Revolution. The First Republic would end with the Caltrini Restoration on 18 August 1810. Throughout most of its existence, the First Republic was governed by the Pantheonisti faction, under a theocratic directorial republican system. The period of the First Republic was characterised by the overthrow of the Grand Principality of Tyrrenhus, the establishment of the Popular Convention, the Aventine Triad, the Pantheonisti led La Purga, its subsequent domination, the Republic of Heaven period, the Revolutionary Wars, La Tempesta and finally, its demise with the Caltrini Reactions and the Caltrini Restoration.

Though the initial revolution within Tyrrenhus established the Popular Convention, infighting between the three principal factions over the direction of the newly formed Republic would escalate into the La Purga, a violent coup d’état instigated by the Pantheonisti. This group, defined by its esoteric mixing of enlightenment ideals and Catholicism immediately issued the Devotion of the Republic to Heaven, which instilled their ideals in the nascent Republic. This was followed by various Bonfires, with each constituting the targeting of a specific culture or supposed threat to the Republic.

Almost instantly in wake of the La Purga, the Republic found itself at war with its fellow Etrurian states, in what became known as the War of the League. The Kingdoms of Novalia and Carinthia together with the Duchies of Dinara and Peravia dispatched armies to restore the Principality, they were successively defeated by the Republic and suffered counter-invasion, resulting in the collapse and annexation of Carinthia and Novalia by 1786. In 1787, the War of the Northern League began, with the recently re-proclaimed Etrurian Republic launching invasions of Carvagna, Torrazzia and Povelia, annexing them with little to no resistance. Fighting between the Republic and the two northern Duchies ended with their annexation in 1789. This was followed from 1790 onward with numerous wars against Etruria’s neighbours, including Paretia and Gaullica. In one of the most pivotal moments in Eastern Euclean history, in 1789, republican armies invaded and occupied Solaria, with the aim of forcing the support of Pope Alexander XVIII, who however, fled to Gaullica. Solaria was duly proclaimed the capital of the Republic, restoring the city as the capital of a united Etruria for the first time since the Solarian Empire’s demise in 475.

During its existence, the Etrurian First Republic instituted numerous reforms. These included the introduction of universal suffrage for men and women aged 21 and over, the abolition of slavery, equality before law, communal property, the banning of interest rates and introduction of debt forgiveness and a codified law system, while a highly modified version of Werania’s Code of the Rights of Man was enforced through law. However, the Republic due to its own paranoia and state promoted mass violence also took to more radical decisions, such as the attempted effort to abolish currency and restore a bartering based economy, price controls and the enforcement of the Declaration of Rights of State, which proscribed the state’s right to use violence against its population. The most contentious issue of the First Republic was its formulation of the Canon of Heaven’s Devotions, a document which served to encapsulate the ideology of the revolution.

Throughout the 1790s, the Republic scored major victories against its royalist enemies. Its capable officer corps, including Giorlamo lodare-Dio Schiave, Augustino Cesare Santoro and Caio Teme-Dio Trellini and the expertly used Nobilis Hospes, providing the Republic with significant numbers of conscripts, all combined to enable the establishment of Ecumenical Republics in Paretia, Piraea, Amathia and Gaullica. However, economic mismanagement, zealotry and ever-increasing violence domestically began to undermine the Republic. Coupled with growing resistance by the Papacy to what it officially described as an “blasphemous and apostatic science”, popular support began to crumble. In 1802, the Weranian Republic collapsed, enabling the other major Euclean monarchies to aid Gaullica. From 1806 through to 1810, the exiled Etrurian aristocracies united around the House of Caltrini, who returned with a sizeable force in early 1810 and overthrew the Republic as the republican armies disintegrated.

The United Kingdom of Etruria was established several weeks later, though as a constitutional monarchy, rather than absolutist. The legacy of the Etrurian First Republic would live on through parliamentarianism, social welfarism, civic virtue enforced by law, egalitarianism, and a deference of state to the Church. The Republic’s wedding of Catholicism with republicanism and nationalism would play a prominent role within Etrurian society through to the 1880s, when the Caltrini monarchy was overthrown, and would leave marks on neighbouring Gaullica and Paretia.

The First Republic would leave a profound legacy in both Etruria and the wider world, ideologically, politically, economically and religiously. It united the territories of Etruria for the first time since Solarian times and would export its unique theocratic republicanism across much of Southern Euclea, leaving an indelible mark on the evolution of the Catholic Church. In comparison to its rival Weranic Republic, the Etrurian Republic’s ideals and principles of popular universal suffrage, utilitarianism, egalitarianism and a Catholicism-infused Etrurian nationalism, would live on almost a century through the clergy and academic circles, ultimately being reconstituted in some form with the Etrurian Second Republic, following the San Sepulchro Revolution in 1888 that overthrew the Caltrini monarchy.

History

Origin

- Grand Principality of Tyrrenhus is ruled incompetently by successive Grand Princes.

- Near two-decades of war between Tyrrenhus and Povelia over central Vespasia has bankrupted Tyrrenhus and become unpopular

- Successive agitation by clubs, societies and groups.

- Bread riots begin over a taxation on wheat

- Bread riots escalate

- March of the Widows, sees guards open fire on war widows demanding better pensions.

- Mass revolt and overthrow of the monarchy.

Popular Convention

- New national convention is established by former parliamentarians and the three prominent revolutionary groups.

- Groups; Rispettabili (gentleman revolutionaries + cult of reason types), Scugnizzo (radical poor, San Coulettes types), Pantheonisti (theo-republicans)

- Inter factional fighting and disagreements

- Grand Prince's execution

- Rising tensions between the Rispettabili and Pantheonisti over atheist and cult of reason

- Scugnizzo destroyed by Pantheonisti

La Purga

- Pantheonisti stage a coup, capturing, exiling or killing the Rispettabili

- Pantheonisti assumed complete control of the Popular Convention and begin building a loyalist base within the republican armies.

- Secures the backing of the Archbishop of Tyrrenhus and the Principality's clergy (overwhelming majority)

Devotion of the Republic to Heaven

- The Pantheonisti devote the republic to Heaven and vow to instil their ideological tenets.

- First Bonfire of the Heresies is launched, destroying brothels, gambling dens and coffee houses used by the upper-classes.

- War of the League begins with Carinthia, Novalia and the northern states invading Tyrrenhus.

War of the Leagues

- The League makes good progress in the north, though the Republican Armies in the west defeat the joint Carinthian-Novalian invasion at the Battle of Valle Gioviana and Battle of Villa Sirena.

- Republican Armies defeat the northern states at the battles of Santa Cecelia, Margo and Ponte di Rubicon.

- Senate issues edict for the counter-invasion of the western Kingdoms.

- Republican Armies invade Novalia toward Supetar and Dubovica, defeating the Novalian armies at the Battle of Paladini and the Battle of Krosvari, the death of King Petar IV from influenza forces a surrender.

- Republican Armies crush the Carinthians at the Battle of Podraga and capture Propoce, destroying the Kingdom of Carinthia.

- The defeat of the two Kingdoms forces the end of the War of the League.

- War of the Northern League begins in 1787, with the Republican invasion of central Vespasia and Povelia - the latter's forced to surrender due to weak governance and popular support for the revolutionary ideals of the Republic. The surrender of Povelia marks the end of the Exalted Republic and the cedeing of its Asterian colonies to the Republic. It also marks the fall of Euclea's most influential maritime republic.

- Duchies of Dinara and Peravia are defeated at the Battle of Nuovo Marena, with near 6,000 dead - this is followed by their surrender to the Republic and their annexation. The Republic controls the entirety of Etruria excluding the Ecclesiastical States in the south.

Fall of Solaria

- Pantheonisti Senate seeks the acquiesence of Pope Alexander XVIII and his official blessing of the Republic of Heaven, as well as his endorsement of its ideology.

- The Senate issues an edict proclaiming the need for a renewed state church and the unification of the Ecumene under a singular political authority. Pope Alexander rejects the Senate's edict and issues an excommunication order for the entire Republic.

- Republican armies cross the Pomerio River into the Ecclesiastical States, they capture Solaria without firing a shot a week later.

- Pope Alexander and a number of cardinals flee to Gaullica by ship, proclaiming the Papacy to be in exile. Cardinals and bishops that remain offer their support to the Republic - pivotal "Blessing of the Soldiery" takes place.

- Senate proclaims Solaria the capital of the Republic, marking the first time the city governed a united Etruria since the fall of the Solarian Empire 1,314 years ago.

La Tempesta and the Bonfires

- Began immediately after the La Purga.

- Various uprisings and revolts in support of monarchies for the restoration of annexed nations would be persistent.

- In response, the Pantheonisti Senate issued various edicts detailing what constituted "counter-revolutionary behaviour", also began mass public events and efforts to police virtuous behaviour.

- Bonfire of the Heresies was a wide term used to describe the crackdown on opponents and rebels, though it would devolve in the targeting of religious minorities, the landed gentry and various enlightenment works and authors deemed outside the "devoted citizenry."

- Bonfire of the Vanities was aimed at disuading sinful behaviour, such as vainity - burning of make-up, perfumes, mirrors and exuberant clothing

- Bonfire of the Treasonous was the targeting of individuals within the Republic who professed loyalty but worked to restore royalty.

- This would escalate dramatically into mass denounciations, score settling and general hysteria. Worsened by the Pantheonisti's reliance on religious hysteria, such as enabling accusations of witchcraft, devil worshiping and heresy, notably without the authority of the Church to do so.

Liberation Crusades

- 1789, Senate issues its Proclamation Ecumenical Liberation, with the clear intent of "uniting the Ecumene under Heaven's Republic."

- Republican armies launch invasion of Piraea, Amathia and Paretia, this is also a pre-emptive strike to prevent the rumoured effort by Gaullica to establish a coalition against Etruria.

- Introduction of the Nobilis Hospes (Noble Host) system of mass conscription. Purges of the officer corps of the Etrurian states is ended.

- TBD

Colonial unrest

Zenith

Decline

Caltrini Restoration

Government

From 1784 to 1785, the Republic’s system of government was chaotic and poorly defined, with competition and administrative overlap between the Popular Convention and the Council of Nine, which formed a nascent collective executive and comprised of three members from three principal revolutionary factions. Vicious infighting and power struggles between the three factions would end in early 1785, with La Purga, the coup d’état launched by the Patheonisti.

Following their seizure of power and the Convention, the Pantheonisti, proclaimed the Devotion of the Republic to Heaven and forced through the Constitution of 1785, which had been written as early 1780. This constitution established the system of government that would remain in place near intact from its inception to the restoration of monarchy in 1810. Francesco Cassio Caciarelli, who was the leader of the Pantheonisti served as First Citizen for the entirety of the Republic's existence, his personal role and leadership has led to many to debate whether the Republic was dictatorship or a legitimate directorial republic.

The Pantheonisti maintained the collective executive through the Supremum Consilium (known more widely as just the Consilium). This body was led by the First Citizen, who in turn was subordinated by the Citizen Superiors. While members of the Consilium were to be elected by the Senate, there was only one recorded election, with the members of the Consilium holding their positions throughout the Republic’s existence.

The Republic was further governed through an immensely powerful unicameral Senate of the Republic, which had the powers of decrees (Edicts), which were inviolable and not subject to review by courts. These edicts only required a majority vote by its 300 members. All members were popularly elected by citizens, with their “constituencies” being formed out of Ecclesiastical dioceses.

The Republic also established a semi-independent judicial branch, comprised of multiple courts with competing and overlapping responsibilities. The most prominent was the Consistory of the Canon, which took a role roughly similar to a supreme court or constitutional court in the modern day. The Consistory of the Canon was tasked with ensuring that legislation by the Republican senate adhered to the principles of the Canon of Heaven’s Devotions. Alongside this court was the Consistory of Virtue, which regulated and police public virtues and punished those in office who failed to live up to them, notably issuing proscriptions of senators. The Consistory of Public Safety was the equivalent of a revolutionary tribunal and was the most expansive court of the Republic, playing a prominent role in La Tempesta and the various Bonfires. And lastly there was the Consistory of the Citizenry, which was a court devised to enable citizens to take the state to task over the violation of their rights, this Consistory however, was abolished in 1796 as it was seen to impede the ability of the Republic to deal with domestic threats, real or perceived.

Democracy

The First Republic introduced universal suffrage for men and women aged 21 and above in 1785, weeks after the La Purga. In the first major election of the Pantheonisti Domination, the revolutionary government put the Devotion of the Republic to Heaven to the people through a plebiscite. As the Tyrrhenian government pre-revolution lacked any certifiable record keeping of its own population, the government opted to utilise the Catholic Church as a means of organising democratic processes. As the churches across Tyrrhenus possessed maintained records of its congregants the Republic mandated that all votes be held on Sundays after Mass – this was further aided by the Senate Edict of the Liturgies which mandated church attendance. The Plebiscite was held on 10 April 1785 and saw just over 4.3 million votes cast across Tyrrenhus, with 88% of votes supporting the Devotion of the Republic.

In practice this mass form of voting was the first within continental Euclea of its kind, though subject to abuse and questionable legitimacy. In the case of elections for the Senate of the Republic, candidates from the 300 constituencies would produce letters which were mass produced for every church in their constituency, this would then be read out by the parish priest. These letters served as campaign leaflets, with the candidates making their case for election. Once read, the priest would then ask the congregation to raise their hands for which candidate they supported, the results from each church would be collated and counted at the seat of the Archdiocese (the administrative divisions of the First Republic were established over the Archdioceses) and then revealed to the candidates. This would be repeated for plebiscites, though often in place of letters would be pamphlets produced by the Consilium with no counter arguments.

Historians have long criticised the Pantheonisti’s approach to democracy, which more often than not relied upon parish priests to influence votes – documented cases by Matteo Giovanni Montecalvo, one of the most reliable writers of the time, revealed that often priests would tell the congregants when to raise their hands, near exclusively in support of the Pantheonisti. However, democracy within the First Republic notably did not exclude women, nor between the propertied or peasant classes and by utilising a vote by hand, it removed any discrimination of the literate and illiterate. Other historians have viewed the use of Churches for the exercising of democracy as a secondary means of further wedding liberty, democracy and the republic to the Catholic faith. Francis George, a prominent historian on the 18th century revolutions wrote, “the Pantheonisti were masters of politics, by strongarming the dioceses into running their elections they truly wedded liberty and functions of the Republic to mass, to the eucharist and the liturgies, while also utilising an unparalleled organised network and structure of communal gathering.”

During its 25-year existence, the First Republic held six parliamentary elections and four plebiscites, each resulting in a resounding victory for the Pantheonisti.

Pantheonisti

Throughout the First Republic's existence, it was dominated at all levels by the Society of the Servants of Christ and the Liberties, though they were more commonly and popular known as the Pantheonisti (lit. Pantheonists), owing to the taverna they met at being beside the Pantheon of Sol Invictus in Tyrrenhus. The Pantheonisti were established in 1779 as a club for religious middle-class lawyers, merchants and academics. By 1782, it began to draw significant support from the city’s clergy and religious lay people.

The Pantheonisti was a markedly united and cohesive faction, that was fiercely loyal to its “Charter of Universal Liberty and Salvation”, which was the modern equivalent of a political manifesto. The Charter detailed its principles (See the Canon of Heaven’s Devotions) and its plans, including the establishment of a “unitary, virtuous, Catholic and free republic.” Unlike its compatriots in the Amathian Empyreal Republic, the Pantheonisti did afford a utopian end goal for its followers, but rather believed and championed the view of the “Heaven’s Republic shall be the chariot upon which we shall reach the Kingdom of God”, insofar that the Republic would provide a second redemption of mankind and erase the near heretical and sinful nature provided by monarchism. Though followings its decisive victories in the First and Second Wars of the League in the 1780s and the Capture of Solaria, the Pantheonisti sought to extend further its boundaries in hope of achieving Ecumenical Unification, establishing a unified republic over all of Catholic Euclea and sister republics in the Episemalist west.

At its height, the Pantheonisti boasted an estimated 500,000 members across what is modern Etruria, and boasted 40,000 within the Poor-Fellow Soldiers of Sotirias and the Republic, originally a collection of Tyrrenhus’ urban poor who served as the “fist of the revolution” and were the primary instigators of La Purga on behalf of the Pantheonisti. The Poor-Fellows would later be deployed with the revolutionary armies.

The Pantheonisti are widely considered be a bourgeois radical faction, owing to its leadership being drawn exclusively from the professional class together with the clergy. Though, Francis George remarked, “though thoroughly bourgeois, its agenda and belief system transcended class and wealth divisions in 18th century Etruria, its appeal was the promise of political and spiritual salvation, while its outward egalitarianism dissuaded mistrust by the peasant poor, uniting the two halves into a fierce and cohesive mass.”

Following La Purga, the Pantheonisti held total control over the Senate, the Consistories and by the mid-1780s, total control over the absorbed officer corps. It ruthlessly punished and persecuted its rivals and enemies, justifying such and its wars as the “second cataclysm of Sodom and Gomorrah.” The Pantheonisti also relied heavily on mass hysteria to sustain its various Bonfires and the Tempest.

Canon of Heaven's Devotions

The Canon of Heaven's Devotions was authored by Leonardo Metello Gruttadauria and Vittorio Arcangelo Maiolo between 1784 and 1786 and was a collection of treatises and pamphlets produced by the Pantheonisti during this time. It detailed the ideological tenets of the Revolution post-Purga and sought to detail the Republic's goals and purpose. It was mass produced for consumption by the literate population and was read out in public gatherings, Masses and feast days.

In Chapters 1-3, the Canon illustrates the dogma of the Pantheonisti and the First Republic. It's most fundamental element is the extension of free will into the political realm by arguing that the gift of free will from God was also the gift of liberty. The Pantheonisti attempted to justify their view of liberty via the Catechism, in which "God willed that man should be 'left in the hand of his own counsel,'" to the Pantheonisti, this manifested the right of man to be the ultimate arbiter of his own life, which was incompatible with the tyranny of absolute monarchy. Numerous Pantheonisti simplified this by arguing that humanity could not theoretically achieve salvation nor exercise its need for good works if condemned to control by others, they questioned the right of control by those without the "spiritual authority, morality nor virtue to be master of universal salvation of nations and the individual." Over the course of the First Republic, this position would evolve toward the ultimate condemnation of monarchism as "inherently sinful," while aristocracy would be condemned as violating the laws of creation, in which all of mankind is born equal before God. The Pantheonisti would cite Psalm 146:3 "Put not your trust in princes, in a son of man, in whom there is no salvation," to further accentuate its claims monarchism denied salvation.

Beyond its views on liberty and free will, the Pantheonisti took to esoteric interpretatons of scripture to justify its wider views on democracy, equality and civic virtue. On democracy, the Pantheonisti argued that this would be the natural product of "free will and liberty liberated." They claimed that in place of absolute monarchy, leaders should be elected not as an exercise of rights, but rather as a means for the populace to determine who was most "virtuous and moral in character", as such any prospective leader should be the first among equals in their religiousity, virtue and dedication to exercising and protecting liberty. On equality, the Pantheonisti position is widely misconcieved to be a be a form of proto-socialism, while it does declare all of humanity to be equal in worth, this does not reach into materialism, rather its limited to equality of rights and equality before the law. The Pantheonisti based this position on Galatians 3:28 and was the principal quote for the "Edict of Universal Liberation in God's Name", which abolished slavery and granted equal legal rights to women.

While the Pantheonisti was rather dismissive of the Solarian Empire and its pre-Sotirian legacy, it did however, pay homage to virtus, the application of fixed public virtues in the citizenry. The Patheonisti claimed that universal virtues adhered by all, would serve as the "mortar of the Republic, that holds the stones in place." During the First Republic, the Pantheonisti resurrected Virtus in its original form as well as applying the "Seven Cardinal Sins and Seven Fruits of Holy Spirit", citing Galatians 5. These collective virtues would be instilled by the Republic in the populace via the pulpit and mass, as well as major public events and republican festivals.

Modern study of the Devotions isolated them to four distinct pillars, alongside their principal verse cited by the Pantheonisti:

| Devotion | Theme | Scripture | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liberty - Libertas | This devotion was the dogmatic and legal basis for the introduction of universal civil rights and liberties - and the abolition of monarchy and aristocracy. | Psalm 146:3 "Put not your trust in princes, in a son of man, in whom there is no salvation" | Princes being sinful creatures themselves and possessing absolute power, were inhibitors of man's ability to exercise its free will (gifted from God) and would endanger the ability of mankind to pursue good works and morality through subservience. Liberty could therefore only be exercised through democracy and a republic, though the Pantheonisti were creative in that they used the verse to state, "in the sons of man the road to salvation is paved with the stones of liberty." |

| Democracy - Dēmocratia | The natural consequence of liberty, rule by the people. Necessary in the need of the people to determine their leaders ability and right to rule via their personal character - religiousity, morality and virtue. As they were elected through Liberty, their rule would be sacrosanct though not predetermined. | Deuteronomy 1:13: "Choose wise, understanding, and knowledgeable men from among your tribes, and I will make them [a]heads over you." | By choosing among themselves, the wise understanding knowledegable, they would be endowed with authority from God, though this would be invalidated if the leaders were to be unworthy of their bestowed authority, as such they would be required to do good by those who chose them and God himself, providing a moralistic, virtuous and faithful government. |

| Equality - Aequitās | As all mankind is made equal in God's image and before him, so too should mankind be equal on earth before temporal law and the republic. Each being would be afforded the same rights and liberties under the Republic, and each would be equally responsible for the maintenance of the Republic. | Galatians 3:28: "There is neither Atudite nor Piraean, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Sotirias Jesus." | As mankind was made equal, there can be no distinction temporally between peoples. Due to the spiritual equality of mankind, the institution of slavery is an evil and an obvious denial of liberty. This would also be extended to women, who should be afforded the equal rights of men under law, even if it did not extend to equality in societal roles. |

| Virtue - Virtūs | Shared civic virtues would be the resilience of the Republic against moral and spiritual decline. Through shared virtues in public, there would be consolidation of the Republic through the body politic, while also making it easier to identify and isolate individuals outside the "Republic's embrace." | Galatians 5:22–23: "But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, long-suffering, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control. Against such there is no law." | The application of select virtues within scripture would provide a framework for civic engagement by the populace, through which they would collectively embattle sinful acts and behaviours. This would provide furhter, the Republic's virtuous society. Notably, the Republic also resurrected various Solarian-era virtues, including virtus, which provided a framework for a "good man" of the Republic, though this would be subsumed by focuses on masculinity and the warrior as the various wars fought by the Republic worsened or turned against it. |

| Obedience - Oboedientia | Once a Republic is established and it is shared among the citizenry, the very same should offer total obedience to the Republic for it is of their own creation, choosing and the product of Liberty. As its leaders are afforded God's authority owing to their elevation by the people, their decisions and the choice of leader itself should be respected by all. | Solarians 13:1-7: "Let everyone be subject to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except that which God has established. The authorities that exist have been established by God." | While opponents of the Republic attempted to cite this chapter of Solarians in defence of monarchy, the Pantheonisti reacted by claiming that God would not call for obedience to rulers who sinned against him and abused his gift of authority. They claimed further that Solarians 13:1-7 would only be viable for virtuous and moral governments chosen by the people through the gift of free will. While this Devotion would later be abused by the Pantheonisti, modern historians read it as a call for the respect of democratic results and at worse, a justification for ultra-majoritarianism or a more draconian interpretation of the general will. |

| Fraternity - Fraternitās | The belief that shared citizenship of the Republic as well as the Kingdom of Heaven afforded fraternity between peoples. This was generally speaking one of the more ecompassing Devotions, in which it covered equality of citizenship, nationalism and desires for the united Ecumene. It sought to consolidate society into singular cohesive unit bound by faith, liberty and patriotism. | Matthew 5:5: "Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the Earth." | Matthew 5:5 was widely perceived at the time to be the ultimate rallying cry of the revolutionaries under the Patheonisti, and was interpreted in two significant ways. The first, was to proclaim the inevitable dominion of creation by the powerless and common people, "the huddled masses on the pews" and inevitable victory of the powerless as they unleashed their liberty through liberation from tyranny. The second interpretation was the unity the common people enjoy through their shared submission to tyranny and despots - "only through unity can the powerless and the meek inherit God's Earth in true liberty." |

As numerous historians have noted, the Canon of Heaven's Devotions serves as physical depiction of the "Etrurian revolutionary social contract", which is markedly different to one found in Revolutionary Werania, the social contract of Etruria's Republic was notably more authoritarian in its approach to defining the end result of democracy (i.e the majority will). While it afforded truly radical policies such as gender, racial and popular equality before the law, it also afforded the Republic significant power over its subjects by virtue of being created by its subjects. The extensive use of scripture and the inherently theocratic nature of the Etrurian Republic, while a procedural consequence of the Pantheonisti's overt religiousity in itself sought to marry key enlightenment ideals with Catholicism, even if it ventured into esoteric interpretation. The Pantheonisti dismissed the Weranic school of reason being mutually exclusive with religion, owing to wider view of free will being reason and rationality and that only through democracy and liberty could mankind truly exercise the Godly gift of free will.

Role of the Catholic Church

Revolutionary Armies

The armies of the Etrurian Republic, since referred to as the Etrurian Revolutionary Army, though at the time, officially named by the Pantheonisti as the “Army of the Republic and Holy Faith in Jesus Sotirias.” It was first founded out of the remains of the Tyrrhenian Royal Army immediately after the execution of Grand Prince Alessandro IV.

Between 1784 and 1786, the initial revolutionary army was noted as being crippled by incompetence, disobedience and disorganisation. Many Tyrrhenian officers had either fled north to other Etrurian states or been imprisoned, exiled or executed by the Popular Convention. This was made apparent during the early stages of the War of the First League, when the revolutionary army disintegrated in battle against the Unio Trium Nationum and the combined armies of the Duchies of Dinara and Peravia. These early defeats resulted in the Edict of the Nobilis Hospises, which instituted general conscription and the establishment of a wartime economy. Together with the Edict, came a series of efforts to rehabilitate royalist Tyrrhenian officers held in prison, through public takings of the “Devotion Oath” and the deployment of Representatives of the Republic to every regiment, as well as reform of the officer corps, enabled the revolutionary army to reorganise and score key victories.

The 1786 reforms enabled the revolutionary army to utilise the experience and discipline of royalist officers, while utilising the fervour and zealotry of the rank and file. While the revolutionary army was outnumbered 3:1 during the War of the First League, its fervour and commitment overwhelmed its enemies. As the Republic scored victories it would inevitably expand its borders, annexing Carinthia, Novalia, Carvagna and Torrazzia by 1788, before annexing Povelia without firing a shot the same year. By 1789, the entirety of modern Etruria, with the exception of the Ecclesiastical States had fallen to the republic. In November 1789, the republic captured Solaria, ending the Ecclesiastical States and forcing the Papacy into exile in Gaullica. Eager to replenish its ranks, the republic expanded the jurisdiction of the Nobilis Hospises edict across Etruria, while also absorbing officer corps when viable.

By the onset of the First War of the Grand Coalition, the republic was able to field an army of 1,200,000 soldiers, one of the largest in the world at that time. The republic throughout its various wars would suffer from continued shortages of cannon and horses, limiting its artillery and cavalry corps, though historians have long lauded the republic’s infantry for its discipline, organisation and fervour. That the republic was able to confront its enemies and score victories even when isolated and surrounded on three sides has also been lauded by historians.

The initial revolutionary wars of the late 1780s, produced many of the generals who would go on to lead the republic to major victories in the 1790s against the Euclean monarchies. These included Giorlamo lodare-Dio Schiave, Augustino Cesare Santoro and Caio Teme-Dio Trellini. However, the tide would turn in the early 1800s, with defeats at the hands of Gaullica, while the collapse of the Weranian Republic in northern Euclea, would enable the entry of Estmere and Soravia into the conflict against Etruria, which in turn soured public support for the republic and the eventual restoration of monarchy in 1810.