Great War of the North

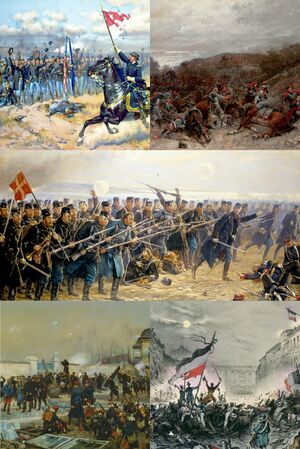

The Great War of the North, known as the War of the Grand Alliance (Tynic: Den store forbundskrig) in Sjealand, was a major conflict in northern Nordania that was fought from 1861 to 1867. The immediate cause of the war stemmed from the violent rising of pan-Valish nationalists in the Sjealandic possession of Valmark, tacitly supported by the Valgravian government. However, much of the cause of the war was rooted in the long-standing interests of Ambrose and Suavia to expand their power at the expense of the declining Sjealandic maritime empire. Many historians assert that political figures, most prominently Ambrosian President Godfred Crovan, deliberately engineered the conflict to achieve their nation's longtime economic and territorial aspirations; thus, the conflict has also been called the Crovanic War. The war drew all of the Nordanian powers into opposing alliances, with combat occurring in the Njord and Tynic Seas, Sjealand, and across northern Aldínn.

Spurred on by the outbreak of revolution in Valmark, and with the support of their allies in Elsbridge, on 12 September 1861 the Valgravian ambassador in Asgård delivered an ultimatum to the Sjealandic government, demanding that Sjealand immediately withdraw from Valmark and allow for a joint Ambro-Valgravian occupation of the territory. King Håkon VII, understanding this would allow the coalition to exert power over the Tynic Straits, refused to accede to the demands, and let the ultimatum expire. Mere hours later, the Valgravian steam frigate Hanskrona sunk the Sjealandic corvette Nordstiernen, marking the start of the conflict. The eruption of hostilities without a declaration of war was immediately controversial, and saw several nations declare their support for Sjealand in the following days—forming the Grand Alliance. Crovan, meanwhile, adroitly organized several nations, including Suavia and Engatia, into a pro-Valish coalition.

Sjealand was quickly able to reinforce the small army of Valmark, prolonging the Valgravian invasion long enough for reserves to be called off. Crovan's army drove into the Frysan states, forcing their capitulation in mid-1862 and establishing a protectorate over the region. Meanwhile, a series of naval actions in the Njord saw the combined Suavian and Ambrosian fleet confine the Royal Sjealandic Navy to port by December 1862, allowing Ambrose to successfully invade the contested Tårnøerne islands. A blockade of the Sjealandic coast was attempted, however this was not entirely successful, as nations such as Galideen continued trade; Crovan would use this to declare war on Galideen and its allies in Urtsokh and Velonia in late 1862. An Ambrosian thrust the following year saw the annexation of Velonia and the collapse of the Urtsokhan monarchy, with Crovan replacing it with a friendly republic. A Valgravian-Engatian offensive in the autumn of 1863 saw the Sjealandic Army virtually expelled from the continent, and the declaration of the Valish unification. However, Kreissau's entry into the war on the Grand Alliance side prompted the Coalition to open peace talks with Sjealand in October.

The peace talks, held in Klarvann were inconclusive, and were effectively terminated after the Engatian delegation walked away from the negotiating table. Crovan had utilized the lull in the fighting to prepare an invasion of the Sjealandic mainland; Coalition forces landed on Sjealandic soil in the spring of 1864 and slogged its way into the interior; by the autumn of 1864, the capital, Asgård, was under siege, and the Sjealandic monarchy and government evacuated to Holmegård. After Crovan's departure from the Eastern Theatre, however, the situation there worsened: a guerilla conflict had broken out in Ambrosian-occupied Galideen, compounded by the resistance of Galideen General Tenawehron; at the same time, the Battle of the Nordvakt Straits saw the break out of the Sjealandic fleet, allowing it to progressively reclaim control of Njord. In February 1865, Crovan was killed during the Siege of Asgård, causing celebration in Sjealand and mourning in Ambrose.

By late 1865, most of the powers had suffered significant losses in manpower and resources, regardless of their victories or defeats. The Valish Army forced the capitulation of Kreissau and its allies in March, yet they were numerically and logistically exhausted. After attempts to pressure the rest of the Coalition to reopen peace talks, Valland unilaterally signed an armistice with Sjealand in May 1866. Concurrently, the Engatian Army in Sjealand was decisively defeated at Nødebo, leading to the breaking of the six-month long Siege of Asgård. A new Engatian government signed an armistice with Sjealand in June 1866, followed by Suavia the same month. This series of events lead to a series of armistices throughout the rest of the year. Official hostilities were ended with the signing of the armistice between Galideen and Ambrose in December 1866.

The Congress of Dalganburgh in 1867 redrew the map of Nordania, cementing Valish unification, Ambrose's annexation Frysa, Velonia and the Tårnøerne, and Suavia making gains in Urthsokh and Orlav. The terms were evidence of a rapid and dramatic fall of Sjealandic power and prestige, causing the withdrawal of Sjealand from continental affairs for the next few decades. Nevertheless, the peace left certain factions in Ambrose unhappy with the results; despite waging a successful land campaign, Ambrose failed to completely usurp Sjealand's naval and trade hegemony, and Galideen remained a critical obstacle to control of the White Sea. This left them estranged from their allies in the Coalition and undermined the very balance of power in northern Nordania that the Congress had attempted to restore. The failure in establishing a lasting peace, particularly between Sjealand and Ambrose, has led to the war being seen as one of the leading causes of the Continental War.

Nomenclature

Great War of the North is generally accepted as a politically-neutral term for the conflict; nevertheless, many countries feature contentious differences in their historiography that are rooted in national attitudes on the war itself. The war is variously known in some countries by their respective alliances: in Sjealand, as the War of the Grand Alliance (Tynic: Den store forbundskrig); in Engatia and Suavia, as the War of the Coalition (Engatian: Gueara da coaliziun, Suavian: Gùerre de la coàlition). In both Ambrose and Sjealand, the Fourth Ambro-Sjealandic War has been historically used. In other areas, too, the war is referred to by its combatants—Velonia and Frysa both refer to it as the Ambrosian War (Velonian: Ambriumi sõda, Frysan: Amblis Guer). In Kreissau, it is the Second Lingenburg War (Kreissauan: Zweiter Lingenburger Krieg), as Kreissau's involvement was directly tied to the status of Lingenburg insofar as Valish unification. Within the Valish states, the conflict is variously referred to as the War of Unification ((Valish, Upper Valish: Enighetskrig, Saarvalish: Oarloch fan ienwurding) or (in Valden) the First War of Unification (Lower Valish: Første foreningskrig).

Due to the highly-visible nature of Godfred Crovan's participation in the war, it is often referred to as the Crovanic War or (rarely) Crovanic Wars. This term is predominant in Ambrose, where Crovan is commemorated as a national hero; however, it has also been adopted into other languages with more negative connotations, particularly by those wishing to depict Crovan as the mastermind behind the conflict. The names War of Ambrosian Aggression or War of Coalition Aggression originated in the mid-20th century, indicating Ambrose and/or the Coalition as the belligerent part(ies) in the conflict (though often used jokingly in the modern day).

Additionally, the war has been controversially described as the first "continental war", though this is also disputed for political reasons.

Prelude

Pre-war Nordanian geopolitics

At the beginning of 1860 Sjealand was the undisputed regional power in Nordania, and the archking of Sjealand ruled over the Viceroyality of Vestmannaland, the Duchy of Hvidmark and several exclaves in Hethland. Changes in the Borean trade had seen a decrease of Sjealand involvment in the spice-trade between the two continents and Sjealand was now focusing its attention on its colonies in Nautasia. The decrease in the Borean trade had left the Sjealandic economy weakened, which the rising states of Swastria and Ambrose had been keenly monitoring. While Ambrose had fought and won its independence from Sjealand in 1691, the Swastrians had long been under the boot of the strong Sjealandic Navy and were effectively locked inside the Tynic Sea. Both states had made signifcant contributions to eachothers militaries, though Ambrose remained stronger, both on land and sea. Throughout the 1850´s their respective governments had been developing cooperative plans for a potential war against Sjealand and its allies in Hethland and Vasturia, in which both states had also been discussing what they would gain from such a potential conflict.

Ambrose had seen its nationalism fanned by the Ambro-Sjealandic Wars of the 1700s and early 1800s; in final war, from 1829 to 1832, the Royal Ambrosian Navy had been humiliated and public confidence in the monarchy fell almost overnight. Unrest in the 1830s and 1840s culminated in the Ambrosian Revolution, with the King of Ambrose overthrown and a Confederal Republic declared. Domestic instability in the early years of the republic led to a military government that hoped to direct the country's popular fervor outwards; this was most clearly visible in the foreign policy of General Godfred Crovan, who acceded to the Presidency in 1860. Crovan, riding a wave of reinvigorated national spirit, sought to expand the country's power and prestige in several ways. Initially, Ambrosian nationalists sought only to take several mineral-rich provinces in Wosrac and Vasturia, many of which predominantly spoke dialects of Anglish. However, Crovan and others came to the conclusion that Ambrose could only becoming a great power by decisively displacing Sjealand from its position as the naval and mercantile hegemon of Nordania — a position which had been slowly eroding for decades. This would be accomplished by an aggressive expansion of the merchant marine, securing control over the Northwest Passage, and fanning nationalism in the Sjealandic Viceroyalty of Vestmannaland, in the hopes of establishing an independent republic under Ambrosian influence. Most importantly, however, this meant seizing the Tårnøerne archipelago — contested since 1691. The Tower Islands were crucial for several reasons; their location made them a prime strategic chokepoint for effectively controlling the Sea of Njord, and their waters were rich for fishing and whaling, which Crovan considered "an economic reserve that has gone tragically untapped." However, Ambrose, fresh out of its revolutionary strife, was dismissed as a third-rate power by Sjealand and others on the Valí Peninsula.

The Swastrian Royal Confederation was a relatively new development in Nordanian politics, and from its inception it had seen itself locked inside the Tynic Sea by Sjealand and its protectorate in Hethland. While almost insignificant at sea, the Royal Swastrian Army had been pioneers of adopting breech-loading weapons and their conscript army received some of the best training on the continent. Bolstered by the Eibenlander Army, which practically operated as part of the Swastrian army, the Swastrians were able to command forces that would almost match the Royal Sjealandic Army in numbers and material. The primary concerns of the Swastrian government was taking the Duchy of Hvidmark, an ethnically Tynic province of the Sjealandic Muspelheilm realm. The province contained some of the richest coal and iron deposits in Nordania along with 5 large port cities that the Swastrians could use for their navy, most notably the city of Hvidby, whose deep water port was shielded by cliffs and strong fortresses, and would effectively guarantee Swastria naval access in the Tynic Sea. Teutonic nationalism, and in particular, teutonic supremacism, had become highly influential among intellectual circles in the decades prior to the war, and writers such as Manuel Steinhäuser and Wendelin Hannawald had harkened back to the medieval Swastrian invasion of Sjealand, citing those ancient borders as what Swastria should strive to conquer. These ideas had won great support among the public, much to the worry of the Sjealandic ambassadors in Wittburg.

In Sjealand many had seen the rise of nationalism as something beneath them as the Sjealandic state was and had been a multi-ethnic state for centuries, albeit with a strong bias towards the central core of ethnic groups and languages. While the Sjealandic government publicly scoffed at the Swastrian and Ambrosian nationalist tendencies, many Sjealandic politicians followed pseudo-nationalistic sentiments in the Rigsdag, praising Sjealand-first policies with regards to Vestmannaland, which saw crackdowns on its language and national identity. These policies had greatly angered the populace in Vestmannaland, which ever since the days of the North Sea Realm had remained staunchly loyal to the Sjealandic Crown, and what had at first been requests to have the Vestmannar people adopted as equals to the groups in Sjealand gradually slid into calls for autonomy or independence. From 1859 to 1861 over 116 riots occurred in the capital of Circevíc alone.

Rising in Vestmannaland

With the increased tensions in Vestmannaland support had begun to pour in from Ambrose and Swastria. The governments began, through smuggling and hidden donations, to send large amounts of money to the loudest advocates of independence. However even with this increased support, the cries for autonomy within Sjealand were larger than those for full independence. Even so an underground movement called the Republican Brotherhood (Repúblikana bræðralag) was formed in the capital of Circevíc in 1852. With the many riots in the city against the Sjealandic rule the movement saw large amounts of public support, quickly rising from simply distributing pamphlets to being elected to the vast majority of administrative seats in the larger settlements of the country. With this the activists, inspired by similar successes in East Borea and Conitia sent a deputation to Asgård on the 10th of September 1861, demanding the immediate recognition by Archking Håkon VII of an independent Vestmannarn republic which would be allied to Sjealand. Archking Håkon's reply, in which he admitted the right of Vestmannaland as an equal partner state to be guided by the common royal diet, but declared that he had neither "the power, right, nor wish" to remove Vestmannaland from the realm, was immediately followed or even perhaps preceded by an outbreak of open rebellion.

3 hours after the Archkings reply, the Vestmannarn Prince Stormur Torsson, the sovereign of the Principality of Hasteinssund took the 1st and 7th Berufeller Rifle Companies along with several students of the Academy of Saxahvall to take over the fortress of Nørrensten in Circevík. The fortress contained the main armoury of all western Vestmannaland, along with the ethnic Vestmannarn 8th, 9th, and 10th Infantry Battalions, the 1nd Regiment of Artillery, as well as some military engineers. As Torsson approached the fortress the gates were opened by the defenders, who cheered on his arrival with military fanfares, opening of beer and wine and impassioned speeches by the local commandant and Torsson. Soon Torsson had secured the battalions and regiment of artillery to the provisional government he soon after proclaimed in Circevík. The 15 Sjealandic officers in the fortress were executed by firing squad and their bodies thrown in the sea while their heads were mounted on spikes. Soon all across western FVestmannaland cities rose in open revolt against the Sjealanders, with portraits of the king burnt along with Sjealandic flags. However in eastern Vestmannaland, where Sjealand had a larger military presence, the uprisings were either unsuccesful or did not happen.

Outbreak of war

The news of the outbreak of open rebellion was celebrated in Ambrose and Swastria; Godfred Crovan reportedly danced with glee in his office upon receiving the news, exclaiming They have handed us our place in the sun. Telegrams were sent to the Swastrian court, where the news were recieved just as enthusiastically. The leaders of both nations immediately set in motion several plans for their already conscripted forces to begin mobilisation. Throughout the rest of August the situation remained tense, and while Sjealandic forces began converging on the Vestmannarn revolutionaries, the Ambrosians and Swastrians both justified their own mobilisations as preemptive measures to deter similar risings occur in their own nation. In reality, however, the two nations had recognized that the situation looked extremely favorable, and began correspondences with the new state of Jorland and Lothican — a traditional ally of Sjealand — promising them significant territorial gains in Vasturia should they join the war. The Baylander King, Lenox I, was particularly receptive to these covert diplomatic overtures.

In Sjealand, the court and government had been suspicious of the Ambrosians for some time, and had issued a general mobilisation only days after the first mobilisations. Furthermore the Archking had been in contact with his allies in Hethland and Vasturia securing promises of military aid should a conflict break out. While these promises were given there was significant doubt about the speed of which especially the Vasturian forces would be able to support the Sjealandic army, which at the time was the largest army on the continent, consisting of 478,000 men in 12 army corps, of which one was in Vestmannaland and one in Hethland. Considerations for the size of the Sjealandic army, its modern railway network and its well-used telegraph network had been taken into account by the now self-styleed Coalition, but these were deemed secondary, and a quick enough push could disrupt the Sjealandic positions.

On the 10th of September a combined Ambro-Swastrian delegation entered Hvidmark on their way to the field headquarters of Georg Andreas Daniel Gerlach, supreme commander of the southern Sjealandic armies, with an ultimatum. In this ultimatum Swastria, Jorland and Lothican and Ambrose, styling themselves as the Coalition, demanded that Sjealand immediately grant Vestmannaland independence and recognize the right of all peoples in Sjealand to decide their own destiny. Additionally the ultimatum demanded that until Vestmannaland had been given full independence Coalition troops would occupy and police several regions of Sjealand, most importantly Hvidmark and the Tårnøerne. The Sjealanders were given 48 hours to issue their compliance with the ultimatum. In Asgård the ultimatum was met with outrage, and the Archking reportedly demanded official apoligies from the Ambassadors of both nations, who had not been informed of their nations intentions. An extraordinary meeting of the Cabinet, the Court and the General Staff was called and discussions were held throughout the 10th until the late morning of the 11th. Assured by his General Staff and Cabinet that the nation would not stand this the Archking had his court contact theatres, operas and public places across the country, with speakers reading the ultimatum out aloud to the outraged populace. Telegrams were dispatched to all garrisons across the country, and to the Sjealandic possessions, preparing them for imminent conflict. With one hour left of the ultimatum, the Archkingdom of Sjealand and her allies preemptively declared war on the Coalition on the morning of the 12th. Having not heard of the declaration of war, but knowing of the ultimatum the Swastrian steam-frigate Der König attacked and sunk the Sjealandic corvette Nordstiernen, opening the first fight of the war.

Progress of the war

Opening hostilities

Battles in the Great Belt

The Royal Sjealandic Navy was beyond a doubt the single greatest threat to all war plans of coalition. In sheer numbers it outnumbered the Swasrian, Ambrosian and Jorvish navies and its ships were all fairly modern with well trained crews. However it was spread across Nordania, Nautasia and Borea with almost a fourth i , and it would take time for the navy to converge on the area of conflict. The Coalition sought to capitalize on this and a joint Swastro-Eibenlander squadron consisting of 4 screw frigates, 1 paddle steamer and 3 gunboats under command of Eibenlander Flottillenadmiral Wilhelm von Monts was dispatched from Holversahn in the 13th with the goal of clearing the Great belt of Sjealandic warships. On the morning of the 15th they encountered a large Sjealandic squadron consisting of 3 screw frigates and 4 screw corvettes under the command of Flottillenadmiral Edvard Svendson. Von Monts ordered his faster frigates and paddle steamer to attack while the slower Swastrian ships lagged behind, unable to effectively engage the Sjealandic warships. His newest ship, the Unterberg bore the brunt of Sjealandic gunfire, catching fire several times, but it was able to cross inbetween the two first Sjealandic ships, firing into both before the fires eventually reached the gunpowder of the Unterberg, which exploded, taking its crew with it. Soon after another Eibenlander frigate was sunk, but the Sjealandic ships were now so damaged that they began taking in water and had to be abandoned, leaving the Sjealanders with only one frigate left. Attempting to retreat they were fired upon by the Swastrians and Eibenlanders, with Svendson deciding for a full on barrage of his remaining ships, which damaged the coalition squadron emough for the remaining Sjealandic ships to escape to port in Hethland.

Throughout the month saw several minor skirmishes between Sjealandic ships, bolstered by Hethlandic against coalition ships. In general the fighting was inconclusive, but this in practice functioned as a tactical victory for the coalition, as inconclusive fighting meant that the Royal Sjealandic Navy was unable to completely close off Great belt, thus making a blockade of the Tynic members of the Coalition less credible, which strategically was of great importance. In addition a naval battle in the Guldensund saw several Sjealandic coastal fortifications on both sides of the sound damaged, limiting the Sjealandic ability to fire on Coalition ships passing through the sound. The constant fighting in the belt did to a degree limit the ability of neutral ships to trade with the coalition states in the Tynic leading to shortages of some wares in Swastria and Eibenland.

In october there were battles at Miklagård, Johanshavn, Isaresmynd and Pekamluk, which were Coalition victories and Tynerhavn, Hageborg, Heðegmynd, Goldhavn and Holmegård which were Sjealandic victories. Additionally there was a battle at Langedyn which saw a large Hethland-Sjealandic naval force engage an aproximately equal Swastro-Eibenlander force, but the battle was inconclusive because of rising storms in late october which saw a general decrease in naval combat in the Great belt as it was too dangerous to fight in the shallow waters littered with reefs and skerries.

Borean Skirmishing

Sjealand had since the 1100s maintained a series of tradeposts, naval bases and treaty ports in Borea and Nautasia and these had for centuries held a stranglehold in the trade between Borea and Nordania, with Sjealand and Tuthina able to deny the ships of other nations passage as the Lahudican archipelago effectively functioned as a shield between East Borea and the Voragic Ocean. Ambrose itself had been involved in Northern Tuthina for some time, particularly in the whaling industry, which had seen the presence of Ambrosian ships in northern Lahudica increase dramatically. By the outbreak of the war this meant that Ambrosian warships were already ready in East Borea, which served the goals of the Ambrosian government well. Sjealand had via its Transvoragic telegraph cable to Tuthina and other cables across Borea alerted its naval forces abroad to the war and had ordered a significant amount of them to return to Sjealand. This was deemed enough of a threat for Ambrose to dispatch its Borean squadron from their bases in northern Tuthina to harrass Sjealandic ships making their war eastwards.

The first skirmishes occurred in early october as a number of Sjealandic and Ambrosian ships clashed off Baiqiao until cannon-fire from the Sjealandic naval quarter in the city eventually was able to force the Ambrosians off, though having damaged the Sjealandic ships enough to confine them to port for months. Further skirmishing occurred off Zhonhe, Kuoqing and Hongzhu in october as well, with a major naval battle involving a dozen vessels taking place in early november off the Xiaodongese capital Rongzhuo, which resulted in a Sjealandic victory, albeit a costly one. In Senria fighting occurred off Misaki, Senkguchi, Kurosawa, Hasiwara, Mashike and Ritsumura. At Ritsumura and Misaki military ships of the local daimyos unwillingly became involved in the skirmishing at great cost, their ships were pummelled in the crossfire, having hardly damaged either the Sjealandic or Ambrosian ships. Tinza didnt experience as much fighting as Xiaodong or Senria but the Ambrosian raiders still managed to engage Sjealandic ships off Ladumra, Cholarabs and Gwarka, all of which were Ambrosian victories.

The Ambrosian operations in Borea were a clear succes for Ambrose as it severely delayed the formation of any credible Sjealandic naval force that could go to Nordania, instead forcing the ships to arrive piecemeal over a longer period of time, which drastrically hampered Sjealandic naval manouvers, which were spread over three naval theatres already. Additionally the clever Ambrosian hit and run tactics, using newer but smaller ships to quickly engage older Sjealandic vessels before reaching safe distances again allowed Ambrose to sink several aging but still dangerous Sjealandic ships, which also helped convice Tuthina to not intervene in the conflict in its waters, as the Imperial Court had grown weary of the Sjealandic presence in the Borean waters, which had been bringing less money into Tuthina compared to what the Sjealanders were earning.

Invasion of Sjealand

Ever since the outbreak tensions had remained high, throughout september, october and november the front had remained relatively silent as both the Sjealandic and the joint Swastro-Eibenlander armies bolstered their forces at the front. This period was described by Sjealandic soldiers guarding the positions on the Sydfjeldene redoubts as unbearable as they were forced to remain on high alert with no release for their tension. Many of the Teutonic soldiers felt the same, wishing to experience the thrill of combat rather than wait in their forward positions. The Coalition had taken minor strips along the border, which Sjealand had allowed them to take, as it set its soldiers into their fortifications in and around the Sydfjeldene mountain range.

The Arhwen River, which constituted the southern border between Sjealand and Swastria lay on a flat plain and had frozen hard, and could be crossed easily, with only the Sjealandic flank positions in Ildre and Valmark blocking a potential incursion. At the start of the war Gerlach had 38,000 men in two army corps or four divisions for the defence of Hvidmark. The strongest of these was the 8th Brigade consisted of the 5th Saxahvall and 18th Asgård Regiments (approximately 1,600 soldiers each). This unit was one of the most veteran units in the Sjealandic army, having fought in war with Ambrose and having put down rebellions in Nautasia and Hethland. Unlike Sjealand, which had focused its defence across all of its border, leaving only the 4th and 1st army corps in Hvidmark the Coalition held only token forces among the rest of the border except for near Hvidmark. The Swastrian army had 35 battalions, 23 squadrons and 14 guns, approximately 35,100 men. The Eibenlander army had 22 battalions, 11 squadrons and 51 guns, approximately 25,000 men. They therefore significantly outnumbered the Sjealandic army in Hvidmark, which while better equipped and heavily entrenched, would have a hard time recieving reinforcements, the Sjealandic railway was only partly expanded into Hvidmark and the roads through the Sydfjeldene were in poor condition. The supreme commander for the Swastro-Eibenlander army was Swastrian Field Marshal Ludwig Graf von Dreichen. The Eibenlander troops were led by General Karl von Humboldt.

Coalition troops crossed the Arhwen into Hvidmark on the 3rd of December 1861 in a terrible storm. The Sjealandic flank positions in Ildre and Valmark were alerted later than normally to the crossing as the heavy snowstorms had limited the use of the old beacon systems and Eibenlander jägers had stormed several telegraph centers hours before in secret, cutting the telegraph lines from the border. The Eibenlander attacked towards the refortified Ildre positions (on the Tynic coast) while the Swastrian forces struck the Sjealandic fortifications at Valmark (near the mountains), trying to overman the fortresses before Gerlach could reinforce them. After seven hours of fighting the Swastrians were repulsed from Valmark and retreated while the Eibenlanders encircled Ildre, which lay on a peninsula and began bombarding the fortress.

The 4,200 men at Salmark attempted to retreat from their positions and re-group with the Sjealandic 1st Hvidmark Division at Arenfjolde (Ahrenviöl) but were attacked by the Swastrians at Hatsted (Hattstedt) on the 7th of december. The battle was immensely brutal as the 4,200 Sjealanders engaged 6,100 Swastrians at close range during a snowstorm at −10 °C (14 °F). This was the first true field battle of the conflict and thus recieved significant attention after it had been fought. One Sjealandic soldier Private Jens Hansen described it:

The weather was terrible, much worse than usual, i could hardly see three ranks in front of myself and almost hear just as little. Suddenly i heard the regimental fanfare and Lieutenant Stokkesen erupting, shouting >The Swastrian! The Swastrian is here< we hardly had time to react. A bullet to the neck took out Stokkesen, he was thrown off his horse, his blood covering two of my friends before another hail of bullets erupted over us. Swastrian lines were approaching from our left. When we jumped into the ditch on the side of the road we could just make their silhouettes out. Our men desperately tried to get our artillery set up, but the Swastrians had already begun firing. One cannonball tore up three men to my left. Another a few minutes later struck to my right, throwing me unconscious but luckily not wounding me.

The brigades losses in this fighting were: Dead, 3 corporals 5 undercorporals 17 privates; wounded, 7 corporals 9 undercorporals 35 privates; missing 23 privates. The Swastrians losses were much smaller, but the remainder of the brigade managed to retreat further inland while the Swastrians moved to Ildre. Dozens of men froze to death on both sides during the marches. Once the Sjealandic soldiers reached the town of Kappel (Kappeln) there were able to utilize its railway northwards, managing to evacuate much artillery, most importantly heavy artillery, which would be critical later during the Siege of Hvidby, however around 1,000 Sjealandic men were unable to use the trains and would have to march to Arenfjolde.

This march has gone down in Sjealandic history as one of the worst experiences that Sjealandic soldiers have been exposed to. It was northwards in a north gale with driven snow, and most of the soldiers had had no rest for the last four days and nights. While not burned with artillery guns or supply carts they had little to no horses and would have to carry most of their gear by themselves. The heavy snow, terrible weather and harsh conditions were gruelling for the men, many of whom originated from the significantly warmer climate of Asgård. Horses could not carry or pull their loads properly because of the snow and ice; riders had to dismount and lead their horses. Artillery guns and carts overturned. The column of men and horses and vehicles seemed endless. While on the march to Arenfjolde the rearguard, consisting mainly of young recruits would have to fight against pursuing Swastrians and Eibenlanders. Some of the young men were so driven with nationalistic fervour towards the Swastrians and anger at their condition that upon being defeated in minor skirmishes some would take their own lives or refuse to surrender, fighting to the death. Near Tumlaus Kog (Tümlauer-Koog), about 11 kilometers south of Arenfjolde , pursuing Swastrians reached them, and in heavy fighting near Yttersum, the 9th lost 50 men dead, injured and captured. On that day eleven soldiers also died of hypothermia.

When Arenfjolde came into view dozen of men collapsed from exhaustion, and had to be carried by arriving medical personell, others died from exposure and shock after arriving in the positions. It had been thought that the tough march through the gruelling conditions would have caused the men to desert, but none had. At the same time, around the 20th the Eibenlanders, under General Eduard Vogel von Falckenstein, stormed Ildre and heavy fighting happened during the battle. The 1st and 11th regiments manned the outposts of the fortress and were commanded by Colonel Anders Håkon Rokkedal. The outposts were overrun after a hard fight, which saw the death of Rokkedal and a large part of the 1st Regiment. Continuing from the outposts the main positions of the fortress were also stormed, with the Eibenlanders seeing significant casualties due to Sjealandic volley fire. After the fortress fell over 500 Sjealanders were dead and 530 Eibenlanders dead.

Ambrosian-Jorvish invasion of Vasturia

Despite Crovan's role in engineering the conflict, he had initially planned to engage the nations of the Grand Alliance piecemeal, as he recognized the small size of the Ambrosian Army — only about 11,000 active soldiers in 1860. Though the army had absorbed many of the state militias upon the outbreak of war in 1860, bolstering its numbers substantially, the levels of training of these troops varied widely from the highly-disciplined regulars to the militiamen. In private, Crovan himself did not feel comfortable leading an army into battle, given that he had never held a large-scale field command before. Thus, he was reluctant to act on calls for the invasion of the Vasturian states, delaying it for a full month. However, political pressure began to escalate to begin campaigning before winter, and the Jorvish minister to Ambrose, Imbert Roorda, warned government threatened to break the alliance and go on the offensive alone if the Ambrosians did not act. Fearing a military coup against his government, Crovan finally relented and called a meeting of the Confederal General Staff on October 18th, 1861. Three armies, with a total of about 30,000 men, were formed: the Army of the Glencamber under General Irving MacDowel, the Army of the Kenetcy under General Erasmus Keyes, and finally, the Army of the Els. The Els was nominally commanded by General Charles Bowell, but was effectively under Crovan's direct command, given that he chose to exercise his role as commander-in-chief while campaigning with this army. Political rivals, namely Generals Nathaniel Banks and Daniel Sickles, had convinced Crovan of the necessity of leading the army from the front; Crovan accepted this while knowing full well that they planned to seize power in the event of his wounding of death.

The northern invasion of the Vasturian states began on October 30th, 1861, with the advance columns of the Ambrosian Army of the Glencamber crossing the River Kenetcy into the Communal Republic of Àrdaodann; after some brief skirmishing, the capital of the republic, Clacheasan, would be taken unopposed the following day. This was met with outrage from many of the Vasturian states, and several would declare war on Ambrose, joining the Grand Alliance. Over the next week, the Ambrosians would march into three more states: Keyes moved his troops along the coast into the Republic of Caol Ròncabhsairean, MacDowel pushed into the Duchy of Gailmuigh-Feannag, and, on November 3rd, Crovan crossed into the Republic of Gailmuigh. On November 5th, the Army of the Els met its first concentrated opposition in the 1st Druidic Army, made up of hastily-assembled components from the militaries of over a dozen Vasturian states — this would be the formation that would eventually grow into the modern Most Serene Vasturian Army. Crovan was able to rein in his subordinates and prevented them from giving battle until November 7th — after two days of evasion and flanking maneuvers, he engaged the Vasturians at Skarloey Creek. While he was numerically outnumbered, Crovan was able to force the Vasturians to march across open fields to attack his lines, which allowed him to maul them with cannon he had captured earlier in the campaign. The arrival of Vasturian reserves were able to prevent a full on rout, but the battle was a decisive Ambrosian victory; the 1st Druidic Army would retreat south on November 9th, virtually abandoning the northernmost Vasturian states to Ambrose — thus Crovan could claim to have liberated the Anglish-speaking peoples of northern Vasturia. This was touted as a major propaganda victory in Elsbridge, and it served only to secure Crovan's political position.

Keyes continued moving south throughout the month of November, however the increasingly worsening weather and his stretched supply lines forced him to settle in for the winter by November 28th, after many of his men died from hypothermia while besieging the port of Òs Uarach. Crovan, emboldned by the victory at Skarloey Creek, ordered MacDowel to take the city of Tuim a‑Staigh, the capital of Gailmuigh-Feannag and an important Vasturian railroad junction, by December; he reasoned that if Ambrose cemented its hold on north-central Vasturia before the onset of the harsh winter, the Vasturians would have little chance of retaking it in the spring, even if by then they had coalesced into a singular political entity (as was looking more and more likely). The key to the city was the Rèidhean Citadel (known in Anglish as Fort Reidan), a massive star fort on the River Kenetcy that overlooked the city itself; the Vasturian garrison, under General Séafra Bruadair Ó Banáin, evacuated the city on November 20th and concentrated his forces in the citadel. Rather than proceed with "all deliberate speed" as he had been ordered to, however, MacDowel bungled the approach to the fortifications and arrived nearly a week behind schedule. After a hasty river crossing made hazardous due to the ice floes, the Ambrosian assaults were bloodily repulsed by the well-entrenched enemy in the First Battle of Fort Reidan. MacDowel concluded that he did not have enough manuever room and settled in for a siege of the city; he was dismissed from command by Crovan shortly therafter, and the Army of the Glencamber was absorbed into the Army of the Els. However, this would be the end of northern campaigning for the year.

Tynic Theatre

Push for Asgård

Battle for Varienland

Beginning of the Eisarean Revolution

Front Stagnates

Sjealandic Counteroffensive

Vasturian Theatre

Vasturian collapse

During the winter of 1861-62, Crovan drastically reorganized the Ambrosian armies, consolidating the various regular and thanedred volunteer units into five armies (creating three more), the largest of which was his own Army of the Els. The large-scale mobilizations had, by this point, delivered him almost 20,000 fresh troops; he had also been reinforced with several hundred artillery pieces, many of them 76 mm Pattern 1861, the first rifled gun to be widely used by the Ambrosian Artillery Corps. He also relentlessly trained the men, drilling the volunteers and militia to a point where outside observers described their level of discipline as "indistiguishable from that of professional foot soldiers". This was largely accomplished through Crovan's personal charisma; his frequent reviews and visits to the front line made him well respected by his men, who began to enthusiastically look up to their general as "Uncle Godfry".

Crovan departed his winter fortifications on February 12, quickly moving his troops to positions immediately overlooking the fort. Though the first signs of the spring thaw had appeared, General Ó Banáin was expecting campaigning to not begin until March at the earliest and was caught offguard by this sudden move, which cut off his army's only feasible avenue for escape. Crovan ordered a flotilla of ironclad river gunboats anchored at Kenetcy Station to break through the the hazardous river ice and sail south to bombard the Fort. After a twelve hours bombardment and the threat of Crovan marching on the now-decimated works, Ó Banáin surrendered. The fall of Fort Reirdan opened the Vasturian River to Ambrosian river gunboats, something that was crucial for the advance to proceed south — now central Vasturian cities like Forsvollr and even Dagmar were threatened.

While the Army of the Kenetcy continued pushing south towards and Kalengia, Crovan quickly capitalized on his momentum and pushed south along the river into the Tauriscian Steppe, where there were few geographic obstacles to the rapid movement of his armies, which became known as "Crovan's foot cavalry". In several engagements in late February and March, he surprised numerous Vasturian garrison units with the speed of his advance, including at the rail junction of Gèadh Fàil, where a cavalry charge personally led by Crovan shattered the defensive cordon around the city. By mid-April, the Ambrosians had reached the edge of the Tauriscian flatlands and threatened to move into the fertile Suevi river valleys below, the region that dominated the food production of much of central Vasturia. The gross disorganization and lack of communication between the separate Vasturian states became apparent; separate armies pursued separate and often conflicting objectives, always unable to concentrate in force before being attacked by the Ambrosian armies piecemeal. At this point, the [INSERT TITLE] of the Republic of Dagmar, Aðalgunarr Sigurðrsson Veðr belatedly declared the Most Serene Vasturian Confederation on April 12th, 1863, the foundations of the modern Vasturian state, in an effort to coordinate the efforts of the Vasturian states against the encroaching Crovan; despite the unilateral nature of his declaration, Dagmar was quickly joined by many of the states fighting Crovan directly, and Geirfinnursson began planning for a counter-offensive to push back Crovan — secretly hoping a decisive defeat would allow them to negotiate a peace where Crovan could dominate Celtic Tauriscia and the Suevi region of Upper Vasturia could remain independent.

Sigurðrsson took control of the various Vasturian armies, reorganizing them into the "New Model Army" and marched north, parallel to Crovan, hoping to swing left towards the Vasturian River and cut the Ambrosians off from their supply lines. Ambrosian cavalry screenings met the first elements of the New Model Army at Killòintean, skirmishing inconclusively there until the Ambrosians withdrew. Crovan chose to have his troops dig in along the ridgeline at the county town of Ruanaidh, inviting the Vasturians to attack. Although Sigurðrsson's commanding General, Bjarni Einarsson Kvaran, had not reached his objective to swing behind the Ambrosians, political pressure urged him to attack — furthermore, he recognized that if he was able to pin Crovan's thin defensive line to the riverbank he could effectively destroy the Army of the Els. Attacking on April 26th, the first assaults of the Battle of Ruanaidh bloodily rolled back the Ambrosian flanks but were unable to completely dislodge the Ambrosian center. Undeterred, Einarsson launched another assault, fully committing his reserves of two corps. This would prove to be his undoing, as he had not accounted for the Ambrosian artillery, under Henry Hunt, placed in a barely-visible outcropping known as the "Raven's Nest". The next two assaults were torn apart by grapeshot fired from the flanks and was crippled by the time it reached the Ambrosian lines. Eirnarsson was at this point faced with an impending counter-charge that threatened to rout his army, and he was forced to retreat back to his earlier positions. With this victory, northern Vasturia was almost entirely under Ambrosian control, and Crovan declared the Tauriscian Confederation in opposition to the Vasturian Confederation. While it consisting of many of the reconstituted governments of the Lower Vasturian and Tauriscian states, it was effectively a puppet state with Crovan himself as president, which allowed the Ambrosians to relax the military occupation of northern Vasturia and free up troops to help move south.

After Ruanaidh, Einarsson's army initially began to regroup at the village of Creag an Fhèidh, on the edge of Tauriscia, but were forced to move quickly after Crovan marched past them to the south, escaping through thick fog on May 1st and 2nd. The two armies hastily skirmished at Druim Laimhrig on May 17th, which resulted in Crovan's first tactical defeat as his corps were denied a crossing of the Vasturian River. Nevertheless, Einarsson failed to capitalize on his victory (largely due to infighting between Tauriscian and Suevi elements of his New Model Army), and with naval support the Ambrosian continued their advance south. With Sigurðrsson recognizing the fragility of the political situation in his newly-formed Confederation, Einarsson was relieved of command on June 2nd, 1862, replaced by Cúscraid MacLeod Mael Lugh. MacLeod, desperate to halt the Ambrosians, mounted a last ditch defense at Séan Laimhrig. The Vasturian line was broken, however, and this defeat allowed Crovan to swing around the remnants of the New Model Army, marching nearly unopposed into central Vasturia. On June 12th, the reserve corps of Botolfur Oelversson, Duke of Hervin, the only remaining concentrated Vasturian force in the area, was shattered by a swift eastward wheel by General Keyes's Army of the Kenetcy, with the remnants abandoning their effort to relieve the Vasturian collapse. In late June, Ambrosian calvary entered the borders of the former Republic of Dagmar; Crovan himself entered this city of Dagmar on July the 3rd. In a last bid to keep Vasturian unification alive, Sigurðrsson signed a truce with Crovan on 4 July at his country estate outside of Dagmar. The Treaty of Dagmar, signed 15 days later, ended the theater of the war; in return for Crovan recognizing Vasturian confederation, Vasturia agreed to serious reductions in its territorial size: Sigurðrsson recognized Tauriscian independence, Ambrosian territorial gains in northern Tauriscia, and furthermore ceded several areas along the border with Cradebetia, Ambrose's ally. Ambrose was allowed free use of Vasturian ports on the Sea of Njord, and Vasturia was forced to pay war indemnities.

Guerrilla War

Renewed offensive and armistice

Tynic Sea

Sea of Njord

Crovan had embarked on a vast naval construction program in 1859, through which he hoped to modernize the Confederal Navy, which, at that point, still relied on fifth and sixth-rate frigates, only two of which were steam powered and none of which were screw-driven. By the outbreak of war in 1861, the Ambrosian Navy had expanded significantly to six paddle steamers and one screw frigate, the CSS Indefatigable, which was named flagship in December. The newly-reorganized Admiralty, however, under Secretary of the Navy Richard Powell, was reluctant to engage the Royal Sjealandic Navy head-on, due to the vast difference in size and strength, preferring to engage in commerce raiding along the Borean coast and leave battle to the Swastrian and Eibenlander navies. Only when Crovan threatened to slash funding for the navy and cancel the shipbuilding program did Powell relent, dispatching the White Squadron from Perth in March of 1862 to protect Ambrosian shipping "through all means necessary".

The Sjealandic position in the Sea of Njord, however, was much weaker than had been anticipated by either side at the start of the war, largely due to the Coalition's hit-and-run tactics in the Voragic Ocean that crippled or delayed the arrival of the significant naval resources that had been guarding Borean trade. First Sea Lord Niels Suenson, conscious of this fact and still wary of the Coalition's naval presence in the Tynic, instead sought to commit minimal resources to the Njord and engage strictly in commerce raiding, reasoning that a disruption of sorely-needed imports would paralyze Ambrose's newly-industrialized wartime economy. However, after six commerce raiders were sunk by the Ambrosians by April 1862, Suenson was pressured to commit the Njord Squadron and seek a decisive battle against the Ambrosians. Suenson directed his subordinate, Admiral H.F. Funch to lure the Ambrosian White Squadron to the Tårnøerne islands in July, where they would be trapped between the guns of the islands' masonry forts and the guns of the Sjealandic Navy. This was unsuccessful, as the Ambrosians were concentrating with the Jorvish fleet in Kaldfesting. Limited engagements and commerce raiding continued on both sides throughout the summer, while the fleets continued trying to track each other in a game of cat and mouse. On August 28th, the fleets sighted each other off of Cape Heria. The resulting Battle of Cape Heria, while tactically inconclusive, caused serious losses to both sides.

Panic occurred in the Sjealandic government as exaggerated reports of a crushing defeat made their way to the press, leading to the sacking of the Lord of the Admiralty and the elevation of Suenson to his place. After the battle, Suenson, pressured by Funch, decided to shift to a strategy of a "fleet-in-being", retreating to the city of Nordvakt, sheltered by islands and the deep Nordvakt Fjord. While this preserved the Njord Squadron as an effective fighting force, it also effectively gave free reign to the Ambrosian Navy in the Sea of Njord. The Sjealandic sea trade was effectively cut off, forcing Sjealandic merchants to rely on expensive overland trade across Nordania. Asgård's control of its outlying territories was also seriously compromised, with an Ambrosian forces under General George Amlodd landing on and occupying the Tower Islands in 1863. Buoyed by their success, the Ambrosians made two attempts, in November 1862 and March 1863, to push past the fortifications guarding the Nordvakt Straits and annihilate the Sjealandic fleet in port, but were repulsed both times. Instead, Powell opted for a naval blockade of the northern Sjealandic coast. An Ambrosian Army force was landed on the outer islands of the Nordvakt strait, occupying a masonry fort and importing ironclad gunboats to prevent the Sjealandic Navy from breaking out.

The Coalition maintained uncontested control of the Njord throughout the rest of 1863 and 1864 (although the effects of the blockade were lessened through blockade runners). However, the Sjealandic Navy, wary of the Coalition's approaching land advance towards Nordvakt, decided to attempt a breakout. Despite the Ambrosian presence at the head of the straits, the Njord Squadron was able to break through the hastily-assembled gunboat flotilla and into the open sea on November 5th, 1864, in the Battle of the Nordvakt Straits. This suddenly threatened the entire Ambrosian blockade, and threw the possession of the Njord back into question. In order to prevent the bombardment of Ambrosian cities, Powell was forced to relax the blockade in early 1865; however, this was not before several cities were bombarded, including Austevoll and Tørnes.

Several large battles took place in 1865 and early 1866, but most were inconclusive. Sjealandic attempts to recapture the southern Tårnøerne in September 1865 failed, and Ambrosians effort to reinstate a blockade failed. Neither side was able to effectively use the Njord shipping lanes during this period, fearing the effectiveness of the other's commerce raiding. this situation would continue until the armistice between Ambrose and Sjealand in February 1866.

Sea of Ice

Northern Theatre

Wosracan Incursion

Upon the news that a state of war existed between Wosrac and Ambrose on July the 24th, 1862, Seren Ceri, the Field Marshal of the Wosracan-Cradebet front, almost immediately issued an order for her Eastern Army to march into Cradebet territory. Ceri's army was the largest peacetime formation of the Wosracan Armed Forces — she was in charge of ninety thousand men — and was made up of 12 divisions, holding a total of 8 cavalry regiments and 21 infantry brigades. Just a week later on the 31st, Ambrose, which had recently sent divisions to Cradebetia in preparation, called in Cradebetia to the war citing their alliance as Cradebetia's reason for intervention. Ceri knew that there would be little time before Ambrosian reinforcements would turn the tide of the front. On the 3rd of August, the first significant combat in the theater would occur; the 28,000-strong Wosracan field army, under the immediate command of General Flunydd Yonne, met the 17,000 strong Cradebet 3rd Army at the border crossing 32 kilometers south of the town of Rivor-sinon. The Battle of the Border, as it became known, was a strategic disaster; despite the Wosracans having eventually routed the poorly-trained and poorly-equipped Cradebetians, the successive frontal assaults on the well-prepared enemy positions sustained a casualty rate (dead, wounded, and captured) of 11,000 men — nearly 40% of the field army's total strength. This was met with outrage in Mulford, with many newspapers and politicians demanding that Yonne be court-martialed. Due to the catastrophic nature of the pyrrhic victory, Ceri chose to pause the invasion and allow her forces to rest and restore their much-depleted strength.

Meanwhile, Wosrac's western front against Ambrose had, initially, seen little movement through July and August, save for some minor raids in the Seather region. Crovan chose to wait to commit troops until the fall of Vasturia became inevitable; it was only after the Battle of Sean Làimhrig in August 1862 that the Army of the Els began moving north overland. Historians further speculate that Ambrose had greatly overestimated the military strength of Wosrac and thus preferred, at least at first, to allow Cradebetia to take the initiative offensively. The relative inaction during the height of campaigning season, coupled with the disaster at the Cradebetian border, influenced Lord Illanis, commander of the Wosracan Western Army, to detach some of his men to join Ceri's forces. This would prove to be a critical mistake, as it left Illanis seriously understrength. However, recognizing the Wosracan position, Crovan attempted to convince the Wosracans that his Army was similarly weakened. In reality, during its journey north the Army of the Els had been reinforced by nearly 7,000 men; he hid this by silently marching many of his largest units during the nighttime, largely stymieing the efforts of civilian spies.

As the Ambrosians moved into Wosrac on September 8th, Crovan was unaware of the Wosracan Army's exact whereabouts; this led to a largely-bloodless campaign of maneuver throughout the Seather that would last for over a month. However, he reasoned that, in order to secure any sort of quick victory over Wosrac, he would need to incapacitate at least one of the field armies before the winter ended the campaigning season. Attempting to lure the enemy into battle, he moved slowly through the river valleys of the Waris Hills, largely avoiding any high ground. He would halt his forces south of the village of Waris Allandary on the 11th of October, giving the impression that he was struggling from a poor supply chain. On the 12th of October, the Wosracan Western Army revealed itself at the head of the valley and assaulted the Ambrosian positions at dawn. Crovan had deliberately weakened his front lines, and allowed his troops to retreat further into the valley, luring Illanis's Army in with him. When Illanis reached the point of almost entirely breaking the Ambrosian center, Crovan unleashed his artillery positioned on the hill faces, sending the attack into disarray. The next day, a cavalry charge routed the Wosracan center, with the flanks being finished off by pincer movements by the II and III Corps, commanded by G. Kembell Warren and Daniel Sickles, respectively. Illanis's army was left utterly annihilated, with 15,000 dead or wounded and thousands more captured.

Despite inflicting brutal carnage on the enemy, however, the Ambrosians had also taken serious, possibly even unnecessary casualties, which historians have determined was largely a result of the chaos that temporarily occurred as a consequence of the feint retreat movements — Crovan would dismiss General Sickles on the 21st for insubordination in relation to these charges. Furthermore, in making it appear to the Wosracans that the Ambrosian supply situation was critical, Crovan had stretched the supply lines so thin that he felt himself forced to severe them almost entirely, instead deciding to "live off the land" through liberal foraging. This decision, though now celebrated as innovational in military tactics, was met with worry in the Ambrosian domestic press, who feared that Crovan's Army would starve before reaching Mulford. Crovan also realised that he had over-estimated the military capability of Wosrac, and consequently, would unilaterally take command of Cradebetian troops and incorporate them into his front. Wosrac, for its part, had been caught off-guard by an overwhelming defeat, and Ceri was now forced to recognize that her armies were now on the backfoot.

Turning Tide

With Illanis's army out of action after the brutal Battle of Waris Allandary, Lady Eira Rhiain was assigned as the new Field Marshall for the western front. At her command lay two Armies, The Hearecester Army, composed of sixty thousand regulars and twelve thousand volunteers and conscripts, was described by herself as "A beacon of hope". The second army which lay in her command was the newly formed, Mulford 'Grey-Bannered' Army. In the wake of the Battle of Waris Allandary, recruitment efforts were put in place in order to rally a small support force for the, now alone, Hearecester Army. Upon it's departure from the Duchy of Mulford, the Grey Army, as they would later be known, consisted of thirty-six thousand former or retired soldiers, eight thousand men previously deemed unfit for military service, and one thousand convicts who were deemed 'safe'.

Despite the impressive feat of raising fourty-five thousand men in less then a month, the Grey Army was heavily criticised around Wosrac, with many newspapers calling it 'The End Of Professional Armies'. In particular, the inclusion of small-crime criminals worried the population as many doubted that criminals would hold the flag of a nation it had broken the laws of. Despite the skepticism surrounding the new army, they arrived in Waris on October the 18th, and began efforts in November to disrupt Ambrose supply lines through ambushes, raids and burning crops in certain occupied towns. This controversial tactic lead many in the western duchies of Wosrac to become disenchanted with the Monarchy, who they saw responsible for the war and their hardship.

Tragedy would strike on the Southern front for Wosrac before the dawn of winter. The Cradebet 2nd Army, lead by General Harold Mann, engaged the weakened Gertland Army, commanded by General Flunydd Yonne, on November the 2nd, in a battle that would be known as the Battle of the River-Bend. General Yonne had recently been struggling to keep the public in favour after his disaster in the Battle of The Border and was worried about another high casualty battle against Cradebet forces. When Field Marshall Ceri learned that Cradebet forces had launched an attack, she personally lead a force of eleven thousand men, which she had detached from the Sunthil Army, to reinforce Yonne. Despite the Cradebet force attacking his army numbering only fifteen thousand, Yonne, who wasn't aware of Ceri's reinforcements, made the decision to retreat. This gave the Cradebet force much needed defensive ground. When Ceri's force arrived just seven hours later, they were caught off-gaurd by the lack of Yonne's army and had little defensive ground. With Cradebetia holding the defensive ground, retreat was not an option. Ceri gave the order to attack, just half an hour after arriving. At the end of the battle Ceri, with most of her detached force, lay dead on the river bend. General Yonne was tried and sentenced for cowardice, a crime which held the death penalty.

The 2nd army continued its progress and marched onwards before reaching the outskirts of Rivor-Sinon, the capital of the Duchy of Gertland, on the 5th of November. General Mann's force stood nine-thousand men strong against the town's garrison of four hundred men and one hundred and twenty enforcement officers. The 2nd Army surrounded the settlement and demanded surrender multiple times. Suprising to the 2nd Army, the town refused. Historians believe this was done in order to burn orders and military information held in the town. The town fell quickly with roughly 100 garrison casualties and 30 civilian casualties. During the winter, the 2nd Army waited in the now occupied town of Rivor-Sinon to be grouped with the Cradebet 4th Army. During this time, a new offensive plan was drawn up by Commander-on-Field Honberg Wittlesfield in order to exploit the recent victory at the Battle of River-Bend. Wittlesfield hoped for a quick and relatively unchallenged march towards Mulford with Ambrosian support from the west bearing the brunt of the Wosracan Armies.

In a similar fashion, the military leaders of Wosrac had to devise a new war plan. It was clear to see that after the humiliating defeats at Waris Allandary and Rivor-Sinon, Wosrac could no longer win the Northern theater without support. A new plan was introduced by the newly appointed General of the Grey Army, Einion Llywellyn, that focused on harassment and the denial of supplies to the Army of Els. Llywellyn, like many other of the military commanders of the nation, was of the belief that any large-scale battles with Ambrosian armies would be disastrous for the war effort and would end in defeat. Instead he focused on splitting the main bulk of Ambrosian forces, The Army Of Els, in smaller skirmishes. While this new strategy was not adopted for the southern front with Cradebetia, Llywellyn was given permission to attempt his new strategy in Spring.

The Slow Spring

To the world's shock, the winter of 1862-1863 was not as long lasting in the Northern theater as initially expected, with the first signs of snow retreating as early as January the 18th. Llywellyn, now officially the General of the Grey Army, decided to attempt his new strategy as early as possible. Llywellyn was aware that the Army of Els currently lived of the land they occupied and were currently resting in Blensow, often sending over considerable amounts of its manpower to the town of Halslow, 14 miles south-west for extra supply. On the 4th of February, 1863, 15,000 men of the Grey Army reached Blensow forest. The town of Blensow lay less than 5 miles north-west of the forest. Meanwhile Llywellyn and the remaining 30,000 men lay in wait in the town of Halslow, to ambush a force of 20,000 men sent from Blensow to collect firewood and medical supplies from the town. When the force arrived Llywellyn immediately attacked. When the Army of Els's General learned of the attack, eager to disable and possibly destroy another Wosracan Army, he left just 4,500 men in Blensow.

In the morning of the 5th of February, the 15,000 men who had been positioned in Blensow forest, attacked the town of Blensow. The town was soon captured, evacuated of citizens and burned to the ground, with little of value left. Meanwhile, in the town of Halslow, reinforcements were sighted by Llywellyn's reconnaissance Calvary. With little time left, the Grey Army set ablaze the town and made efforts to destroy the farming and fishing districts. The Grey Army would successfully disengage before the reinforcements arrived. After the battle, The Army of Els had lost two valuable supply towns, and were forced to fallback to the town of Guceni, 36 miles away.

Despite the seemingly miraculous victory, even Llywellyn knew that this was only a delay tactic, and not a popular one. On the 17th of February he recieved orders from his field marhsal to never burn down a Wosracan town again. By February the 26th, The Army of Els was on the move once more, and had completely destroyed the Army of Hearecester in the Battle of Douglas Bridge.

Eastern Offensive

Following the declaration of war between Ambrose and Aurega in March 15th, 1863, Aurega was quick to react. Already having mobilized its troops in the past year, the Fyddyn Ayrgenig had available 18 divisions, with 12 cavalry regiments and 29 infantry brigades in total, amassing roughly a hundred and twenty thousand men. Cradebetia's attention had been focused on Wosrac, with the tide of war turning against Wosrac thanks to joint action with the Ambrosian army. Before the Cradebetian army could fully reinforce its eastern border, the Northern Army under General af Rhys began an intense push, spearheaded by the 7th Infantry Division, one of Nordania's best mountain warfare units at the time. The attack met the bulk of enemy resistance, with the Cradebet forces swiftly maneuvering to react properly. However, the attack did succeed in slowing down reinforcements in the south even more, allowing General af Reaghan and its Southern Army to attack with less resistance. Advances were considerable in the first two weeks, yet the poor infrastructure in the area — primarily swampland — reduced any hopes of the Auregan forces in advancing any further. Their concerns were confirmed with the official capitulation of Wosrac, on June 7th, 1863, and the rapid movement of the bulk of Crovan's army, along with the Cradebet Army now being free of any threat in the north and west.

By the second week of April, Auregan positions in the swamplands of central Cradebetia faced for the first time Ambrosian units; the newly-formed Army of the Arles under General George Grayman met the Auregan 11th Infantry Brigade at Unasby on April 14th. The Arles was formed from veteran units of the Vasturian and Wosracan campaigns, and, while small, their training and war experience proved to be ruthless; nevertheless, a bold Auregan defence, bolstered by the 2nd Cavalry Regiment which had arrived as reinforcements, repulsed this initial assault. However, as the week passed the swampy area proved less and less favourable to hold a stagnant defence, given the spring mud severely compromised the land and water transports of the area for both forces. Noticing the problem, Auregan generals decided to begin a controlled retreat on the Central part of the front, slowly pushing back while still offering resistance for the advancing Ambrosians. Meanwhile, in the far north at Lellisa, the IX Corps of the Army of the Rappahannock under Renweard Stuart met the 13th Auregan Light Infantry Regiment and the two units began skirmishing. Amidst the harsh winds and snow, the Auregan lines held, and Stuart paused his advance as he waited for his supply trains to arrive overland from Cradebetia. A general Auregan counteroffensive in late April was met with strong resistance by the Ambrosians, with the arrival of the Cradebet 2nd Army allowing the Coalition to push back slowly, especially following the controlled retreat in the central front. Crovan and his Army of the Els arrived from Wosrac in late June of 1863; at this point the numerical superiority swung decisively in favor of the Coalition.

Crovan in particular had aimed for a swift push into Aurega proper, with a decisive defeat of the Auregan army allowing him to march to Ker Dunnain and force an armistice, as he feared the Ambrosian military was overextended already, and that Ambrosian ground forces had made little contribution to Sjealandic campaign. He had, however, seriously underestimated not only the competency of Auregan forces but also the the potential for issues related to the region's lacking infrastructure; the Aurego-Cradebetian border was marked by mountains and tundra in the north and dense forests and swamps in the south, both with few roads. Crovan's doctrine of "living off the land", which had worked brilliantly in Vasturia and Wosrac, became difficult to implement in the agriculturally barren area, and he was forced to couple himself to an unreliable overland supply chain for food and munitions. Furthermore, insurgent activity in Wosrac and Vasturia continued to pose a problem for the Ambrosians. However, the situation was not ideal at all for the Auregans — outnumbered two to one, it was known by the high command that they would not be able to sustain the front like that for much longer. The Auregan government issued martial law and provided for yet another wave of mass conscription, widening the age requirements.

During the summer of 1863, the momentum of the Coalition armies continued to grow, despite the bloody attrition offered by the Auregan controlled retreat. Crovan was able to defeat an isolated Auregan corps at Gerwyn on August 2, and fought inconclusive engagements at Llanfair and Aghadoe in August and September; however the decisive battle he seeked eluded him. The Auregan forces never concentrated into a single field army, and the terrain made it difficult for Crovan to destroy even individual formations. Furthermore, now the armies were on Auregan territory, which afforded better infrastructure and emplacements, as well as popular support, to the defenders. Nevertheless, progress was being made, and Crovan, faced with compounding problems in Vasturia, gave Coalition command to Grayman and returned west in September. It was not until late fall in 1863 that the front slowed down yet again, with the mud coming back and temperatures lowering. As winter began, the situation only worsened. Skirmishes were few, especially in the north, where troop's survival was already in trouble even without the threat of enemy contact. Despite the harsh weather, Auregan light infantry would take this opportunity to make frequent incursions to raid enemy camps for supplies and intelligence. These raids culminated in a raid of the Auregan Mountaineers, who sneaked in the Ambrosian camp at Kilgarvan during the New Year's festivities on January 1st, 1864, killing and capturing several officers. Despite the propaganda value of these raids, however, they proved little importance beyond the operational level.

The Auregan home front faced a complex situation. With the Sea of Ice frozen, the Wosracan pass controlled by the enemy it was unable to trade at all with Sjealand, which was relevant in the country's imports. It was forced to look south, using a considerable portion of its gold reserves to begin stockpiling on material and food from Conitian nations such as Nameria and Ravetia, with the government already fearing the worst for the next year.

The Auregan government's fears proved to be well justified. Crovan returned from Elsbridge in February and, frustrated with the lack of progress that had been made the previous year, quickly began plans for his next push into Aurega. On the 27th of February, 1864, Cradebet and Ambrosian forces began their campaign, which involved swift maneuvering and rehearsed, highly-coordinated feints. General Anwas and his Northern Army attempted to anticipate and stymie the enemy's movements, however after the first two weeks of near-constant movement the exhaustion in the Auregan ranks was beginning to show. The first major battle of the campaign was fought on March 29th, at Callahan; the Coalition's rapid pincer movement forced the Auregan 1st Cavalry Regiment into a rout to escape encirclement. The aftermath of the battle had a ripple effect, and the consequent retreat of the Center Army caused the Auregan Southern Army, still holding their own, to retreat in order to avoid being flanked. General Conall attempted counterattacks multiple times in this retreat, almost encircling Cradebet forces multiple times and inflicting heavy casualties, but the initiative was already lost.

Crovan realized the gap he had created between the Southern and Central Armies, and took the opportunity to attempt to smash Conall and his Southern Army, which would allow him to take the important rail junction of Tylis and, through the elimination of Conall's force, would leave the road to Ker Dunnain open. Racing to engage the Auregans, the two armies met in the Battle of Rhynie on 28 April. The largest and bloodiest single-day action of the theater, it resulted in a tactical victory for the Ambrosians, with the Auregans routed and forced to abandon Tylis. However, strategically both Crovan and Conall recognized it as a failure, given that the heavy Ambrosian casualties seriously reduced the Coalition's offensive capabilities, at least for the next few months; thus Ker Dunnain remained out of reach. Despite attempts to force another feint on the far northern front, it remained stagnant, with Auregan Light Infantry units competently defending against Stuart's lone corps — the terrain could hardly support further troops. With the Auregans protected on their flanks by familiar mountains, Crovan abandoned his plans to dislodge them by spurring the sluggardly Stuart into action.

By May 1864, the west bank of lake Lydn was conquered, and Crovan rode into Tylis on May 6th, with the garrison fleeing south. The Auregan front was now divided clearly in North and South, with Lydnhel, Aurega's most important city in the west, now accessible by waterways to the enemy. The movement did not slow down, with the Auregan forces doing their best to fight in the dense forests of their hinterlands. Crovan again left the front in June, and Graymane, assuming command, decided to avoid seeking another major battle, instead attempting to maneuver towards the capital through farmlands past the forests, which the Auregan military and population of the country heavily relied upon.. Despite the revised strategy, the Coalition advance continued to take casualties at a higher rate than the Auregans; Grayman rejected caution in his approach and instead reasoned that the Coalition could draw far greater pool of manpower than Aurega alone. In July, the Coalition took Caragh, securing their access to the road network leading to Lydnhel; a large offensive followed suit. General Anwas af Rhys was quick to react, ordering the reformation of a defensive line further in the interior; he also instituted a scorched earth policy, ordering peasants to take "all they can carry" from of their homes to Lydnhel, with the soldiers burning what they could not bring with them.

The intentions of General Anwas was to not let Ambrose and the Cradebets have access to the breadbasket of Aurega. Losing control of this area could have disastrous repercussions in terms of the domestic food supply, despite the Auregan government's stockpiling of produce in order to distribute it in the cities if the situation so required (having predicted an Ambrosian breach from the forests in May). Anwas was also conscious of the fact that Ambrosian supply lines were nearly stretched to their limit, and denying them a local food source was a major priority. Ambrose, however, still had enough in the stockpile to fuel their offence successfully. By November 1864, both the Fyddyn y De and the Fyddyn y Tuath had retreated dramatically, with the Coalition on the doorstep of Lydnhel. Their supplies, however, were running low right before winter.

Aurega's scorched earth policy did have severe consequences, however. The internally displaced inside Aurega resulted in a dramatic strain in the country's cities further away from the war, with Ker Dunnain and Korraen alone having received over 400,000 internally displaced individuals. Others, that could not afford to go so far, sought refuge in Lydnhel, with the cities' population of 260,000 at the time almost doubling solely due to migrations caused by the war. The city was already stockpiling food and made sure to secure its access to water from the lake to prevent poisoning, with the infantry forces in the area helping the city in organizing settlements for the homeless and volunteers aiding the government in distributing the food. Rationing was implemented all over the region, with citizens allowed two loaves of bread and a bowl of soup a day. Many died on their way to the cities, some of disease, caused by the high density of people together, others of famine, and others caught in the way by advancing Coalition forces and not spared.

Lyndhel campaign

After the slow, brutal maneuver warfare of the summer and autumn of 1864, both armies had eventually ceased their campaigns by November. After having received word that Crovan would not be returning to the Auregan front for the immediate future (instead moving his command to Sjealand), Grayman set up winter quarters for the exhausted, depleted Army of the Els at Caragh. However, General John Albert de Risbaek and his mainly-cavalry Army of the Glaslaine devised an ambitious plan to drive a wedge between General Anwas' army and the city of Lydnhel.

Executing a coordinated attack along the front, de Risbaek was able to defeat a hastily-assembled force at Refail on December 4th, rapidly moving into a position to threaten Anwas' unprepared army. Forced between choosing abandoning the Lyndhel or risking their fragile winter supply lines, the Auregans had no choice but to retreat, in order to maintain the integrity of their army. The Army of the Glaslaine, bolstered by the Cradebetian Household Guards as well certain infantry regiments from the Army of the Els, proceeded to encircle the city. Inside the pocket remained the Auregan 7th and 8th Infantry Regiments, stationed at the city's core, and the recently formed 19th Infantry Regiment—outnumbered almost three to one. De Risbaek's forces did not attack immediately, however, due to having left their siege equipment (along with much of their supplies) at Caragh.