User:Tranvea/Sandbox Misc

| Normalisation Modernisation and Harmony Campaign | |

|---|---|

| Part of Zorasani Unification, Rahelian War, Irvadistan War | |

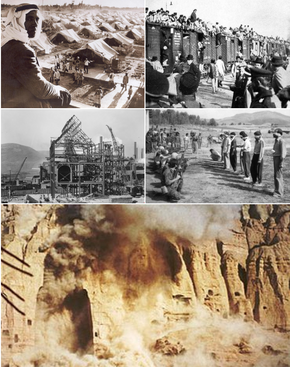

From top-left clockwise: A resettlement camp in Khazestan (1956); Togotis being transported by train to Lake Zindarud; Rahelian tribal leaders before a firing squad (1979); the destruction of the Great Zohist Monument in southern Pardaran (1982); Construction of one of many factories in new industrial cities | |

| Location | Union of Khazestan and Pardaran, Zorasan |

| Date | 1951-1988 |

| Target | Political opponents, Gâvmêšân, ethnic minorities, and occupied territory citizens |

Attack type | population transfer, ethnic cleansing, forced labor, genocide, classicide, |

| Deaths | 980,000-3,980,000 |

| Perpetrators | Zorasani Revolutionary Army, UCF |

| Motive | Modernisation, industrialisation, urbanisation and internal stability |

The Modernisation and Harmony Campaign (Pasdani: کرزیر نوژزه و توفیق; Kârzâr-e Nojāze va Tavāfogh; Rahelian: حملة التحديث والانسجام; Ḥamlat Taḥdīṯ al-Insijām) was a thirty-seven year state campaign conducted between 1951 and 1988 by the Union of Khazestan and Pardaran, and its successor state, the Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics, aimed at stabilising and modernising the country. It ran from the beginning of Zorasani Unification and eight years after its completion, and involved the forced relocation of ethnic minorities, ethnic cleansing, cultural genocide, rapid industrialisation, urbanisation and classicide. Between 1950 and 1988, an estimated 16.4 million people were relocated from their homes to different regions of the country, of these, roughly 8.2 million were forced to live in new industrial cities and new agricultural lands, while numerous cultural norms and systems were dismantled, including Rahelian tribes, nomadism and the repression of minority religions. By its end, between 980,000-3,980,000 people were killed directly or indirectly during the campaign, urbanisation rose from 15% to 64% by 1988 and Zorasan emerged as one of the most industrialised countries in Coius.

The Modernity and Harmony Campaign was devised by the government of Mahrdad Ali Sattari during the late stages of the Pardarian Civil War as a means of rapidly modernising the nation, to prevent the return of the colonial powers and to provide the state with the economic and industrial base from which it could militarily achieve unification. Sattari and his inner-circle identified a variety of "obstinate elements" of Zorasani society and culture that held the nation back from modernising into an economic and political powerhouse, this included certain ethnic minorities, the Rahelian tribal system, Steppe nomadism, wealthy landowners and their political opponents. The ruling ideology Sattarism, included a focus upon what it termed "modernity" (Ḥadāṯa), this was an all-encompassing term denoting the necessary adoption of technology, science and industry as well as the corresponding social changes needed to achieve "modernity." Sattarism also blamed these "obstinate elements" for the Etrurian conquest of Zorasan and Euclean domination, and would need to be destroyed to avoid a repeat. The targetting of ethnic and religious minorities for relocation was justified under claims that these "strategically placed peoples" would be most resilient to unification and adoption of a unifying Zorasani culture and indentity, therefore their homelands or areas of concentration would need to be broken up. The primary targets for relocation were Togotis, Kexri, Chanwans, Yesienians and adherents of Badi, in most cases hundreds of thousands were displaced and their former homes resettled by either Pardarians or Rahelians as a means of diminishing their concentration within geographical areas. Those displaced were re-setteled thousands of kilometres away, in either pre-built housing districts around new agricultural lands or industrial cities, or in some cases, forced to construct their homes from scratch in isolated areas. From 1958 to 1981, the campaign targetted perceived enemies of both the state and the campaign itself, who the government dubbed Gâvmêšân (Pasdani for Buffalo, in apparent reference to their "stubborness"), this group included tribal leaders, critics of the Sattarist state, socialists, wealthy peasants and shepards, monarchists and those related to the Pardarian, Khazi and the northern Rahelian royal families; the latter targeted mostly during the Rahelian War.

The campaign began to drawdown by 1985 and was officially dissolved in 1988 by order of the Central Command Council, which proclaimed the Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics, "unified, stabilised and introduced to social harmony." While the campaign delivered rapid urbanisation, industrialisation and modern technologies, it also significantly disrupted the lives of millions, who were evicted and transported away from their communities or places of birth. The attacks on cultural uniqueness of the various minorities has led many to accuse the campaign to have engaged in cultural genocide, while the cost in lives from both direct violence and indirectly through resettlement has led others to describe a viable case of ethnic cleansing and genocide. The replacement of resetteled minorities by Pardarians and Rahelians also draws much continued condemnation. Today, it is a criminal offence in Zorasan to refer to the campaign as a crime against humanity.

Background

Sattarism and Modernity

The overriding origin of the entire campaign was the ideological influence of National Renovationism. Developed during the Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command’s period of exile in northern Shangea, it adopted what Akbar Salami describes as the “Cult of Science and Industry”, which in turn was conceptualised as “Hadatha” (حداثة) – a Rahelian word meaning ‘newness’ or ‘modernity.’ Hadatha and its ‘Cult of Science and Industry’ would encapsulate the National Renovationist view that the more industrialised and technologically advanced a country was, the more powerful it was compared to others. Modernity, therefore, was written as a reaction to the Etrurian conquest of Zorasan – Etruria was more industrialised and advanced compared to the Gorsanid Empire, which in turn was condemned as backward, sentimental and too de-centralised to confront or defeat the encroaching colonial powers. If Pardaran, and later Zorasan, was to survive a return of colonialism, it would need to rapidly industrialise and modernise to reduce the gap in national power. From Modernity or Hadatha, would spring forth all subsequent actions and plans of the Campaign, including the eradication of agrarian ways of life, nomadism, tribalism and in the extreme, select minorities deemed to be a threat to modernisation or societal cohesion.

Akbar Salami, a leading historian on the Campaign explains that the desire for modernity would require a complete transformation of society, from an agrarian one culturally and societally wedded to the soil, into an urban and industrial one. This he believes, explains the often-violent plans to eradicate cultural norms intrinsically linked to agrarian life.

Salami and other leading researchers have also argued that this transformative campaign was also envisioned as a means of establishing a new “modern society”, implementing Ettehâd and abolishing the “old divisions and sentimentalities” that condemn Zorasan to colonial rule. Through the transformation of society and its adoption of modernity, a collectivist, totalitarian society could be constructed in which the labour and activity of all citizens is dedicated to the greater good of the state and population, and a society in which the needs of the individual are sacrificed voluntarily.

The founding of the Union of Zorasan in 1952, also influenced thinking toward the Campaign, notably, Mahrdad Ali Sattari’s repeated fears of the vast oil and gas reserves held by both Pardaran and Khazestan – he feared this would further entice Euclean powers to return, but also with some degree foresight, feared a wilful dependence on petrochemicals for state finances. He described petrochemicals on numerous occasions as the “Black Opium”, and saw industrialisation as a means of averting both scenarios. The Black Opium moniker would define Zorasani economic policy for the next 70 years to this day.

Legacy of Euclean colonial rule

Beginning in the early 1820s, the Gorsanid Empire was slowly subjugated primarily by Etruria, this process initially began with the seizure of At-Turbah and Zibakenar in 1821 and 1822 respectively as a means of combating corsairs that attacked Etrurian shipping in Solarian Sea. Through these occupied ports, the Etrurians steadily forced open the Gorsanid Empire into one-sided trade agreements, ostensibly for Etruria to secure a monopoly on trade altogether. In 1839, the Etrurians occupied the Riyadhi Peninsula following a failed local uprising, this was followed in 1843 with the occupation of the entirety of Irvadistan in the First Etruro-Gorsanid War, as well as the cities of Chaboksar and Ashkezar. This led in 1849 to the near outbreak of war between Etruria and the Kingdom of Estmere over the formers efforts to achieve monopolisation, leading to the Treaty of Virgillia, which forcibly granted Estmere control over the Gorsanid port cities of Khusavar, Bandar-e Sattari and Bandar-e Daryush, in exchange, Etruria was granted rights over the remaining territory of the Gorsanid Empire. This culminated in the Second Etruro-Gorsanid War (1852-1858), which began with the assassination of Shah Akbar Reza II by his brother Fereydun Reza I, who then instigated a series of attacks on Etrurian-held territory. Vastly outmatched in terms of technology and military training, the Gorsanid Empire ultimately collapsed with the occupation of the entire empire under Etrurian rule, this was formalised in the 1860 General Solarian Ordinance, which divided the Empire into two Dominions of Cyracana and Rahelia Etruriana, and two Protectorate-Generals Ninavina and the rump Pardarian monarchy, the Sublime State of Pardaran under the Zarafshan dynasty. As Protectorate-General, the Sublime State would provide Etruria with exclusive trade access and submit to total Etrurian control over its resource development, infrastructure, defence and foreign policies, while retaining control over several internal affairs.

From 1860 to 1941, there was little in the way of difference between how Etrurian approached the economies of both its Dominions and Protectorate-Generals, a reality that would be consistent under both the monarchy and Second Republic, though the political realities would differ considerably over time. Etruria unlike its peer colonial powers did not engage in settler colonialism, rather that sought solely to militarise its colonies and focus on resource exploitation and development. Though they found no discernable industry within the Gorsanid Empire by 1860, they did however, discover a vast territory of fertile farmland, thick and lucious forest and rainforest and deposits of coal, iron ore, copper, tin and gold. Petrochemical reserves would be discovered in the late 1930s, but the Solarian War would limit development to select fields off-shore and on-shore in Khazestan. As such, Etrurian colonialism was driven by the need to extract resources for processing and refinement in metropolitan Etruria, including foodstuffs, coal and iron ore which fuelled Etruria's industrial revolution. Overtime this would lead to great disparities between coastal Zorasan and the interior, with Etrurian development being near-exclusively focused on the port-cities and the infrastructure linking them to the resource rich interior and farming regions, while simultaneously, maintaining the agrarian-centric way of life found prior to the conquest. Furthermore, the Etrurians only mechanised cash crop estates to boost productivity, leaving many staple crops farmed in ways unchanged for centuries. This resource intense policy would leave Zorasan in 1946, with an overwhelmingly rural population, the among the lowest rates of literacy among the post-colonial nations and once vibrant mining and farming industries bereft of the technology, management and financial support it had come to depend on.

This meant, that upon the onset of the Campaign in 1953, the National Renovationist regime would be tasked with lifting the country at least 100 years behind the Eucleans into the modern age at breakneck speed, if to avoid the near-paranoid fear of the Euclean powers returning to reassert hegemonic control over the post-colonial world.

Initial plans

Plans to begin a modernisation campaign were initially drawn up in 1947, shortly before the outbreak of the Pardarian Civil War. A series of meetings of the Union Command Council in the summer of that year, identified the foundations of what would later be used in 1953 – the need to transfer populations to cities, to boost power production and water supplies for those cities, modernise and expand infrastructure, mechanisation of all agricultural lands and to boost output of capital goods, consumer goods and {[wp|construction materials}}, all the while, boosting output of resources to supply industrial needs, export those resources for the securing of financial assets and doing so without overly disrupting economic life.

It was also during these meetings the Modernisation Campaign also steadily took up issues relating to ethnic and sectarian minorities living in Pardaran. Many members of the Command Council expressed concern that certain groups would pose greater threats to modernisation than others, while some used this as a cover for more chauvinistic prejudices against those minorities. In a series of Command Council reports distributed across the National Renovation Front throughout 1947 and 1948, it was revealed that the Front feared those it described as Xareji (translated into either ‘Alien’ or ‘External’), those who did not “conform to the realities of Pardarian life.” These included Zoro-Satrians, brought over from Satria Etruriana under the Etrurian Second Republic, Yeniseians, Chanwanese, Badists, Sotirians and Zohists. In a report dated July 1948, the Command Council agreed, “the establishment of a modern, industrial and martial society is best achieved through the absence of the External, for cohesion of the spiritual and national forms.” These concerns would be carried over to the 1953 Command Council Decree that launched the Campaign and the plans themselves, indicating a pre-meditation to the massacres that would take place against these groups.

The original 1947-48 reports also identified the need to secure foreign support and expertise to facilitate the campaign, especially in the design of new industrial cities, power plants and factories. At this time, the PRRC was not recognised internationally, particularly the victorious allies of the Great War and Solarian War, with the latter having recognised the Sublime State of Pardaran as the sole legitimate authority over non-Rahelian Zorasan. This would change with the founding of the Union of Zorasan in 1952, where the Union secured support from the All-Soravian Union of Republics and Werania in the development of cities, factories and infrastructure.

The initial plans also laid the groundwork for the necessary literacy drive. Owing to the nature of Etrurian colonial rule, literacy in post-1946 Pardaran was a mere 20.69%, though this rate rose to 26.46% when including Khazestan and Ninevar. The literate population was limited to the port cities and civil servants among the Pardarian, Khazi and Kexri Republic elite, it was determined that in exchange for assisting in the literacy drive, this elites would be spared imprisonment or execution. The PRRC’s military forces were also notably literate and constitute the core of the drive, with soldiers and officers dispatched across the country to teach reading and writing to adults and children, even as those adults were being resettled and tasked with building cities and factories. This was expanded in 1948, to include the establishment of technical institutes to educate a new class of engineers and workers, again, even as they assisted in the physical building of the factories that would employ them.

However, these plans would be put on the hold with the onset of the Pardarian Civil War (1948-50), the Khazi Revolution in 1952 and the intervention in the Kexri War which would all lead to the founding of Union of Zorasan of Pardaran, Khazestan and Ninevar.

1953 Union Command Congress and Khomentah

Following the end of the Kexri War, the countries of Pardaran, Khazestan and Ninevar united to form the Union of Zorasan, re-establishing the first unified Zorasani state since the Etrurian conquest on 2 December 1952. On the 3 January 1953, the first Union Command Congress was held in Faidah, where the plans for modernisation drawn up by the Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command between 1947 and 1948 were presented. The plans were met with excitement among the delegations from all three Union Republics, and on the 4 January the Command Congress voted to approve the plans, appointing Hossein Khalatbari by vote, as Union Minister for Modernisation and Harmony. Under direction of Supreme Leader of the Union Mahrdad Ali Sattari, the Command Congress also approved the establishment of the Union Committee for Modernisation and Industry (خمیته اتحاد نوجوان و توفق; Khomiteh-ye Ettehad-e Nojāze va Tavāfogh; known by its acronym of Khomentah). Khomentah would go on to serve as the umbrella body tasked with overseeing the Campaign until 1988, it would be granted considerable power over provincial governments, resources and manpower, though would remain accountable to the Union Command Council alone. Khomentah would also operate four sub-committees, literacy, industrialisation, urbanisation and harmonisation. The organisation also boasted unfettered access to the Union Ministry of Finance, Union Ministry of Mining and Forestry Affairs and the Union Minister of Labour and Mobilisation, within months of the Campaign's beginning, these ministries would all but become subordinate to Khomentah.

On the 10 January, Khalatbari as the newly minted Union Minister for Modernisation formally established Khomentah in Zahedan. Granted extraordinary powers by the Union Command Congress, Khalatbari with assistance from Deputy Union Minister Qadir al-Suwais established an administrative framework for Khomentah, its subordinate bodies would be comprised of Province Committees (خمیته استان; Khomiteh-ye Ostân; KHOMOTAN), each chaired by a Governor-General (استاندار; Ostândâr), these Governor-Generals would hold ultimate power over their respective provinces, subordinating the provincial central committees entirely. The Khomotans would provide Khomentah with all necessary data, progress reports and would serve as the coordinators for local efforts. The Khomotan, like its umbrella body, would be sub-divided into four sectors covering literacy, industrialisation, urbanisation and harmonisation. However, in 1958, harmonisation would be transferred entirely to the State Commission for Societal Protection.

From mid-January through to early June 1953, Khomentah conducted a widespread study, collating the works of prospectors, geologists, urban planners and the first newly arrived advisers from Shangea, All-Soravian Union of Republics and Werania. The completion of this study was dispatched to the Union Command Council on 10 June for review, on the 13 June, the Command Council authorised the study and the Campaign was officially launched.

The campaign

First Phase 1953-1958

The First Phase (اَوَّل مرحله; Marhale-ye Avval) began on the 13 June 1953 and would continue until the 13 November 1958 and would see dramatic results. Notably, the Campaign was not defined by arbitrary objectives or quotas, but rather by end dates – the Command Council was averse to instilling rushed efforts or promoting dishonest reporting by Khomentah, as the principal drive behind the Campaign was ideological and not pressing fears of conflict or invasion, there was a ‘culture of comfortability’ around the pacing of industrialisation efforts.

The First Phase is defined by its mass deportations of populations, rapid industrialisation (though at rates below expectations), dramatic increases in literacy and urbanisation. The Phase is also defined by the Zorasani-Satrian genocide, creation of the Habsedar prison camp system and crackdowns on cultural norms and traditions in rural areas.

Industrialisation

Industrial Cities

Land Reform

Deportations and massacres

Results

| Products | 1953 | 1954 | 1955 | 1956 | 1957 | 1958 | Total increase from 1953 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cast iron, million tons | |||||||

| Steel, million tons | |||||||

| Rolled ferrous metals, million tons | |||||||

| Coal, million tons | |||||||

| Oil, million tons | |||||||

| Electricity, billion kWh | |||||||

| Paper, thousand tons | |||||||

| Cement, million tons | |||||||

| Sugar, thousand tons | |||||||

| Metal-cutting machines, thousand pieces | |||||||

| Cars, thousand pieces | |||||||

| Leather shoes, million pairs |