History of Midrasia

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Midrasia |

|

| Timeline |

The history of Midrasia as a distinct entity can be traced back to the Fiorentine ages, when surveyors of the region referred to the area of what now makes up Midrasia as Padania, within which the Mydran, Valenian, Ejicii and Pardii tribes lived. Nevertheless, this region did not extend down into modern day Riviera, which was regarded as an independent entity. The Padanian basin would soon come to be absorbed by the expanding Fiorentine Empire, with the regions population coming under significant Fiorentine influence in terms of language, politics, culture and demographics. With the collapse of the Empire, a significant number of invading Germanic and Slavic tribes invaded the regions, establishing a number of new kingdoms within the region which came to be known as the Mydran Realms.

Although these new states were dominated by outsider tribes such as the Burgundians and Goths, these groups quickly integrated into Fiorentinsed society, adopting local customs, cultures and language. This period also saw the expansion of the Alydian Church throughout the Padanian region as local rulers converted to the religion, acknowledging the supremacy of the Pontiff of Laterna. The central location of Midrasia in Asura buoyed many of these states through land and maritime trade, with significant centres of trade developing in Lotrič, Mydroll and Almiaro. Whilst much of the middle ages saw the semblance of a balance of power exist between the various Mydran kingdoms, the accession of Louis IV to the throne of the Kingdom of Piemonte saw this balance broken, with the Pontiff crowning Louis as "King of all Mydra". The subsequent war saw the establishment of a unified Midrasian Kingdom throughout much of the southern Padanian basin.

During the Fifteenth-Century, the newly unified Midrasian kingdom used its newfound position of power to expand within Asura, taking territories in Riviera and North Padania. The newfound wealth of the kingdom also allowed various Merchant guilds to fund exploration missions around the Atlantic Channel and beyond in hopes of accessing Yidaoan trade that had been disrupted by the fall of the Volghari Khanate. These voyages soon put Midrasia in contact with Eastern Rennekka and Majula, giving the Kingdom access to goods previously unavailable to Asuran markets. With the growing prosperity of Midrasia, a burgeoning merchant and gentry class formed, sparking an intellectual revolution in the kingdom, known as the renaissance. This period was characterised by significant developments in art, science, religion and political philosophy, with a revival of Fiorentine culture being the most prominent aspect within Midrasia. Nevertheless, these new political ideas would prove detrimental to the established orders of the monarchy and church, with the Civil War of 1629 seeing the execution of King Henry V and the decline in Pontifical authority.

Immediately following the Civil War, the country was beset with a period of significant unrest, with the new republic embroiled in wars with its neighbours and internal revolts. Nevertheless, the development of a modernised military allowed the central government to maintain its authority and establish the Old Republic, heavily based on Fiorentine ideals adapted from the Ancient Republic of the First and Second-Centuries BCE. However, disagreements over the strength of the central government would see a new civil war break out in 1784, ultimately ending in a victory for Chartist democrats, who sought the establishment of a limited government infused with Liberal ideals and Conservative organisational principles. It would be this new political system which would allow Midrasia to significantly expand overseas, particularly in Majula and Yidao, whilst undergoing radical industrial development at home. Despite this, the late Nineteenth-Century would see considerable turmoil with the outbreak of the Perpignan War and later Great War, which wrecked havoc on Midrasia and Asura as a whole.

Although Midrasia was victorious in the Great War this victory came at a heavy cost, with huge loss of life and infrastructural damage. The reconstruction era would be further hampered by an international recession in the late 1910s. Additionally, the expansion of the Aeian Socialist Union put a significant damper on any feelings of post-war prosperity. In 1928 war broke out with the ASU, with the conflict ending in a bloody stalemate and significant paranoia about communist uprisings at home. The revolts of 1937 saw these fears become reality, leading to the election of the right-wing National Coalition who oversaw a policy of rearmament and political clampdowns. However, by 1953 fears of communism had lapsed somewhat seeing a return to normalcy with the election of the centre-left Social Democratic Party, who oversaw a period of considerable growth in wealth and living standards. However, by the 1970s this prosperity had ended, with debt-fuelled expenditure nearly bankrupting the country. As a result, Consul François Bourgogne saw the implementation of various neoliberal reforms, privatising state held assets and deregulating industries, paving the way for the modern Midrasian economy. In later years, this would be reversed somewhat with investment in key manufacturing industries and socially progressive legislation. Though rising political corruption would culminate in the 2016 Midrasian Spring which toppled the Vauban government and led to the election of the current Consul, Melcion Portas.

Prehistory

- Main article: Prehistoric Asura

Archeological evidence from southern and western Midrasia suggest that early humans may have inhabited the region as early as 1.7 million years ago. Though anatomically modern humans may not have been present until around 33,000 BP.

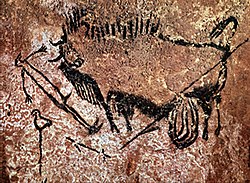

Flint tools and fossilised remains have been discovered across much of southern Midrasia, though particularly within the Vaellenian basin which appeared to have been a hotbed for early human activity. It has been suggested by some historians that this high level of activity was due to a large presence of Glennmorens within the area, a group whose main reach was centred around north-western Asura. Nevertheless, these groups disappear from records around 30,000 years ago, suggesting that they were out-competed by human populations who arrived during the Upper Paleolithic. The vast majority of evidence for human activity within this period comes from remains of tools, particularly spear tips which indicate the presence of large hunter gatherer communities. Cave paintings have also been found within Mydroll and Vaellenia, with the Laone cave network being the best preserved. Paintings within these caves usually depict hunters or animals, particularly bison, aurochs, horses and deer suggesting that these animals were regularly hunted by local communities.

As global temperatures began to rise around in around 15,000 BP, human communities began to migrate northwards, with complex societies developing within the southern regions of the country, particularly around the Viure and Alpiens river valleys. The majority of these groups began to develop agricultural communities, subsiding on fish and cereal crops such as wheat or oat. Around 1300 BCE these societies began to develop complex bronze working techniques, marking the beginning of the Bronze Age within Asura. Evidence suggests that these settlements engaged in a maritime exchange of metal production, particularly with the Chalcian and Latin city states. The onset of iron working would grow this maritime trade considerably, leading to the development of a complex trade network across the Asur and the rise of Chalcian city-state settlements.

Ancient history

Chalcian colonies

Between 600 and 400 BCE maritime trade links around the Asur led to the rise of a number of Chalcian city states along the southern Midrasian coast. The most prominent of these settlements were Almiaro and Argolis (modern day Argois) making them some of the oldest cities within Midrasia. These states soon developed into thriving centres of local trade, operating independently from the various Chalcian realms to the east. Though much of this trade continued to rely on metal production, other goods such as fabrics, animals and crops began to be traded throughout the early Asur network. At the same time, complex settlements also began to develop further inland, particularly within Riviera and Mydroll in which large agricultural settlements began to develop.

Nevertheless, northern Midrasia remained primarily tribal, with sedentary Padanian and Germanic groups more common within central Midrasia, and the nomadic Ejicii common throughout the north-western regions near modern day Cuirpthe.

Iranic invasion

Despite occasional skirmishes between local tribes the majority of groups within the Midrasian region lived in relative peace. This changed around 400 BCE with the arrival of the Iranic Empire of Artakhshathra who had conquered much of the territory of western Catai and east Asura. The conquest continued into the Padanian basin at a blistering pace through Artakhshathra's usage of war elephants and heavy spear infantry. Later Fiorentine sources suggest the Iranic conqueror waged a brutal campaign, completely levelling settlements that fought against him, whilst sparing those which surrendered. Historians have doubted this claim however, suggesting that Fiorentine historians such as Laberius sought to depict the savagery of Artakhshathra in contrast to a benign Fiorentine Empire. Nevertheless, archeological evidence suggests that a number of settlements were severely damaged by the Iranic conquest, though the surrender of cities in the Rivieran valley would be integral to the rise of the Fiorentines several decades later. Whilst the Iranic Empire leave little in the way of a cultural legacy in Asura, the expansion of the empire led Iranic fire worship to spread into the region. This religion would ultimately form the basis of Alydianism which would develop over the following centuries.

As the empire began to expand westward it faced significant resistance from Aquidish tribes and Glazin city states. Nevertheless, the death of Artakhshathra around 350 BCE led to the collapse of the Iranic Empire and its division among his top generals. Despite attempts to retain stability in these new states, the thinly spread Iranic forces garrisoned in cities were easily defeated by local tribes or former vassals who had previously surrendered to the Iranics. It was during this period following the collapse of Artakhshathra's empire that the Rivieran city states of Laterna, Marsala, Monza and Nissa agreed to form a political union under the rule of the King of Laterna who would provide military protection for the various members of the Fiorentine League.

Fiorentine Midrasia

- Main articles: Fiorentine Empire, Betrayal at Mydroll

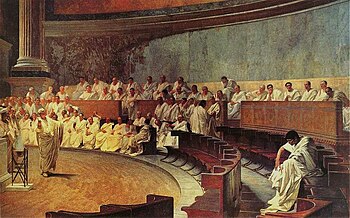

The newly established Fiorentine League, (sometimes referred to as the Fiorentine Kingdom) began to prosper from its newfound independence, engaging in maritime trade with Chalcia and the Troparcan city-states. However, the new political union quickly came under threat from local tribal confederacies, particularly the Leccii who sacked the capital of Laterna in 290 BCE. During this sacking the city's library was destroyed and with it a large number of early Fiorentine sources. The ensuing crisis following the sacking of the city immediately led to the beginning of the first Fiorentine Civil War which saw the cities of Marsala, Monza and Nissa revolt against the Laterna based monarchy due to its inability to defend the league against invading tribes. The result of the war saw the monarchy deposed and a new Republic declared utilising a system of direct democracy in combination with an elected Senate.

Under this new government, the Fiorentines were able to expand their military and subjugate their neighbouring states, expanding their domain into much of modern day Riviera and Aquidneck. As the Republic expanded numerous Asuran tribes assimilated into Fiorentine culture, adopting their language, customs and religion. By around 200 BCE Fiorentine attention turned towards the Padanian basin which had remained untouched by Fiorentine influence, besides a small number of traders and scouting missions. Conquest of southern Midrasia was undertaken with relative ease, with the Fiorentines establishing numerous settlements and fortifications such as Midrium and Lorelicum. These new settlements attracted large numbers of Fiorentine migrants and land in the south was handed out to veterans of the Fiorentine legion. Through this process the traditional culture of the region was displaced by Fiorentine influences, with governing institutions conducted in Fiorentine and rebellious groups displaced across the empire. Soon much of southern Midrasia became fully integrated provinces, governed by the Senate rather than the military.

It wouldn't be until around 50 BCE that the Fiorentines would make a conscious effort to conquer northern Midrasia. Successive generals stationed in provinces such as Midrisium had viewed the north as a region of ungovernable turmoil and disorder, populated by rabid barbarian tribes, however Titus Faenius Iustus' appointment to the governorship of Viurium changed this with a number of campaigns organised to subjugate the region. Titus' writings on his campaigns provided great insights into his activities and thoughts on the region, giving considerable insight into society in northern Padania. Titus' campaigns generally focused on a policy of divide and rule, setting local tribes against each other before swiftly defeating any remaining resistance. Throughout his time in Padania, Titus had successfully occupied much of the region when he heard word of a huge Padanian army marching of Lorelicum. As such, the general was forced to make a hasty retreat south known as the "Hundred Day March" culminating in the Battle of Lorelicum which saw the Padanian tribes narrowly defeated, confirming Fiorentine control over the north.

Titus Faenius Iustus, Commentaries on Padania and its people, Book I, Ch.2

Despite the conquest of the northern region, the various provinces carved out of Padania remained military frontiers throughout the remainder of the empire, subject to regular military presence which guarded the frontier around modern Newrey. In consequence, as the empire began to decline the region was subject to significant migration from local tribes, particularly Germanic, Gothic and Burgundian peoples. These groups significantly undermined Fiorentine control of Padania as they migrated in large groups and did not adopt Fiorentine customs and loyalties. The empire's political control was further undermined as its bureaucracy became increasingly militarised and the modern Alydian religion began to take shape following the Rebellion of Faith.

By around the Fifth-Century, Fiorentine control of the Midrasian region had come under serious strain, resulting in the abandonment of Padania in 457 CE. This situation was exacerbated by the sack of Laterna in 482 with an Imperial remnant, centred on the province of Midrisium took shape, attempting to hold onto the remaining loyal provinces. Through a number of military campaigns, the remnant was able to recapture Laterna in 485 but not without taking on a heavy debt through the hiring of a mercenary army. The wavering loyalties of its army, which was led by Germanic and Gothic generals was ultimately the undoing of the remnant which collapsed on 15th September 493 following the assassination of Emperor Salonius Narcissus at the hands of self-proclaimed King of Mydroll, Marciús Braga at an event known as the Betrayal at Mydroll. The collapse of the empire allowed barbarian tribes to swarm into the former imperial provinces, conquering the regions for their own independent realms.

Mydran Realms

The collapse of the Fiorentine Empire in Midrasia in 485 paved the way for the rise of a number of smaller political entities across the region. Germanic, Gothic and Burgundian migration led to a large demographic shift within northern Padania, which became a battleground for the various feuding clans which had made the journey west. Nevertheless, political life within the south remained somewhat stable, with the invading tribes generally continuing existing Fiorentine administrative structures. However, the barbarian conquest did lead to a new social order, with tribal clansmen viewed as the societal elite, governing over a Fiorentinised Alydian population which generally held few political rights. It has been suggested by historians that the refusal of tribal leaders to adopt Fiorentine cultural practices led to the entrenchment of the Alydian religion within the local population and the increasing influence of religious orders such as the Marceline Monks. Throughout this period, as local populations became more resentful of their foreign rulers and raids from northern tribes began to grow, the rulers of the southern kingdoms came to adopt more decentralised forms of governance, with local rulers granted considerable autonomy to govern their holdings as they saw fit. It is through this process that feudalism began to develop within the Mydran Kingdoms, with the previous warrior classes transitioning into a more administrative landholder role. It is also through this decentralised system that landholders gradually began to convert to Alydianism, undermining the authority of their rulers who continued to worship pagan gods.

By the Eighth-Century however, social unrest bolstered by barbarian invasions, cultural inequality and economic decline led the rulers of the southern kingdoms to begin adopting local customs, in defiance of their ancestral ways. The final pagan ruler of the south, Toussaint of the Burgundians, officially converted to Orthodox Alydianism in June 891. Thus, the Alydian church's hold on the Mydran kingdoms was formalised. This period also saw the construction of numerous stone fortifications and castles along the northern frontiers in hopes of wading off further barbarian raids. Historians generally agree that the success of these fortifications was integral to the development of settled feudal societies in northern Padania, as raiding became increasingly difficult. By the onset of the Eleventh-Century the Mydran realms included the Kingdoms of Ibbeny, Mydroll, Padania, Piemonte, Toussaint and the Republics of Ardougne and Argois. Some historians also include the Kingdom of Tolvas and the Republic of Almiaro as part of the Mydran realms, although these polities generally had a much different cultural makeup than the strictly Midrasian realms.

Throughout the period, the various kingdoms of the Padanian basin had come to adopt a semblance of a balance of power, with alliances forming and breaking based on territorial considerations. Historians specifically point to the formation of the League of Nantes in 694 in an attempt to stop Ibben expansion as the beginning of this period. Numerous coalition wars took place throughout the period, ensuring that no one power would become a regional hegemon. Nevertheless, this did not stop Robert I of Toussaint from acceding to the throne of Mydroll in 1092. Despite a small skirmish in the Battle of Le Cheval which ended in Toussaintian victory there was little opposition to the unification of Toussaint and Mydroll, given the former's relative weakness in regional politics. Over time however this came to change, as the Kingdom benefited from intellectual talent at the University of Mydroll, overseas trade and militarily expansion into Tolvas and Rhone which went unchecked by the other powers of the region.

Alydian Crusades

Midrasian involvement in the Alydian crusades was mixed, with the various Mydran kingdoms playing only a minor role in the crusades of the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries, whilst playing a much larger role as their relative power expanded in the subsequent centuries.

Very few Mydran rulers involved themselves in the crusades in North Arabekh against the Irsadic Caliphate and its successor states, though many rulers sent financial aid and allowed Holy Orders to recruit in their lands. Nevertheless, several prominent members of the Midrasian petty nobility took part in the First and Second Crusades, such as Hector de Beaux who played a prominent role in the capture of Sannat. Despite their relative inactivity during the Arabekhi Crusades, the various Midrasian kingdoms did prosper significantly from the new trade links with the new Alydian Crusader States of Aramas and Torroso.

The Midrasian kingdoms did however play a dominant role in the crusades against the Kingdom of Marchia during the Eleventh-Century. The persecutions of Alydians in southern Newrey and raids into Padania had put the Pontificate on edge for some time, leading to a call for a crusade in the year 1019. This call was mostly answered by the newly formed Midrasian Holy Order, the Knights of Savoy. The order, with financial backing from the Midrasian kingdoms and Vaardeburen Confederacy invaded the Kingdom of Marchia, swiftly defeating their forces within the Elsouf Valley and laying siege to Cyningburgh. As a result, the Marchian king, Æthelstan was forced to retreat to the old capital of Norlynn. Cyningburgh soon fell to the Knights of Savoy who carried out a massacre of the city's non-Alydian population, a matter which continues to strain Mydro-Newreyan relations to this day. The conquest of the Knights continued northwards, with their victory effectively confirmed with their defeat of Marchian forces in the Battle of Barford Field. With Marchian forces routed, the Knights were easily able to lay Siege to Norlynn which lasted for 423 days until Æthelstan committed suicide, leading the defenders to open the gates to the besiegers. Under the rule of the Knights of Savoy, the Newreyan Kingdoms were united under the rule of the Patriarch of the North, whilst stability was maintained by the Knights. This form of rule known as the Bishops System would last for around two centuries.

The Midrasian Kingdoms were also heavily involved in the crusades against tir Lhaeraidd during the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. During the Lhaeraidh Crusades, Alydian forces were able to successfully capture the regions of Shiresia, Vaellenia and Hlaanedd which each became a new Crusader state to defend the frontier against the Lhaeraidh. Proselytising efforts throughout these territories were commonplace, with Midrasian preachers and inquisitors regularly operating within the new states, enforcing church attendance and persecuting dissident non-conformist Derwyedds. This conversion effort was far more successful in Vaellenia and Shiresia, with Hlaanedd's Derwyedd maintaining a large underground presence. Whilst crusading efforts attempted to conquer and convert the entirety of the Lhaeraidh region, they were unable to make significant inroads westwards, due to the boggy inland terrain of the Lhaeraidh lands which proved unsuitable to the Heavy Cavalry of the Alydian forces. Additionally, the church had become embroiled in a struggle against the Ksaiist Pontificate in south-western Asura which had made a number of attempts to preach in Alydian realms such as Aquidneck and Shiresia. By the mid-Fourteenth Century the momentum behind crusading movements had ground to a halt due to numerous military defeats and a growing emphasis on internal struggles over foreign religious threats. Furthermore, the growing power of religious orders, such as the Knights of Savoy had drawn the ire of Alydian rulers, leading to a purge of a number of organisations on the grounds of corruption heresy. The majority of religious military orders had been dissolved by the mid Fifteenth-Century, though regular clerical orders such as Monastic Orders were allowed to continue operation and even prospered significantly over the following decades.

Midrasian unification

Sixty Years' War

In 1309 following the death of the childless Alois VI of Piemonte, Louis IV of Toussaint was designated his successor, as per the late monarchs will. Historians have suggested that the decision to designate Louis as heir to Piemonte was done so to spite King Marcus II of Ibbeny who had an ongoing feud with Alois. This ascension of Louis to the Piemontese throne was disputed by the monarchs of Ibbeny, Padania and elements of the Piemontese nobility on the basis that the Alois was not of sound mind and that the union of Toussaint and Piemonte would break the existing balance of power. A meeting between the rulers of each kingdom was organised at Taveaux in the hopes that war could be avoided. A settlement to allow Louis to rule as king of all three realms, but to be succeeded by a member of the Piemontese nobility in his new acquisitions was rejected, leading to the outbreak of hostilities in August of 1309. Louis' claim to Piemonte was further bolstered when the Alydian Pontificate intervened on his behalf, crowning him King of all Mydra in the hopes that the new ruler would crack down on heretical movements in Piemonte and defend the Pontifical Domain from growing Aquidish influence. This new title also effectively gave Louis a legal claim to the thrones of Ibbeny and Padania, further angering the Toussaintian opposition.

The first battle of the war took place at Hémstoir between Toussaintian and Piemontese noble forces who attempted to resist Louis' march on Norai to officially claim the throne of Piemonte. The battle ended in a narrow victory for the Toussaintians who were able to penetrate into Piemonte, gathering support from supportive nobles within the kingdom. Whilst Louis was off campaigning in the west with his army however, the combined forces of Ibbeny and Padania had marched into Toussaint, laying siege to border fortresses along the Viure and generally pillaging the countryside. Whilst a Toussaintian rear guard was able to respond under Gérôme Le Tonnelier, it proved insufficient to beat back the assault, forcing Louis to retreat from Piemonte to beat back the onslaught. It was during this campaign, at the Battle of Fours that Louis IV was killed by a stray arrow. Many expected that the death of Louis would bring about the end of the war, though his son Louis V was able to rally the nobility around his cause and continue the war. However, much of the Piemontese nobility turned away from Louis V, in hopes of regaining favour with the Piemontese interregnum council.

By 1314 the Piemontese council had elected Adrià de Cambrai as King, forcing Louis to move on the kingdom once the Ibbenian-Padanian offensive had been repulsed. By 1316 Toussaintian forces were once again on top, having driven away the attackers and advanced into Piemonte, taking Ardougne and Neufchatel. The Toussaintian army sought to meet the Piemontese in open battle as a prolonged siege would give the Ibbenians and Padanians time to attack Lotrič. Attempts to draw out the Piemontese proved fruitless, forcing Louis' army to set up a siege at Bordieu, costing valuable time and manpower. However, following a 66 day siege, defectors within the city opened the doors to the invading army, allowing the Toussaintians to take the city much earlier than anticipated. The prospect of further defections concerned the Piemontese, leading them to plan a last-ditch battle against the Toussaintians with the aid of the Padanians and Ibbenians. However, the Toussaintians through their diplomatic efforts were able to draw the Duke of Alpiens into the war, turning the tables at the Battle of Hombourg and giving them a direct path to the Piemontese capital of Norai. The siege of Norai lasted two years, with the city finally falling in 1320, allowing Louis to officially be crowned King of Piemonte. This however did not end the war, as the Padanians and Ibbenians had managed to set up a siege of Lotrič whilst Louis was out west. Despite this, all three remaining kingdoms were considerably strained by the war effort, leading to a ceasefire in 1324 and an opening of negotiations. During these discussions, the rulers of Ibbeny and Padania indicated that they were willing to accept Louis' rule over Piemonte, but that he must renounce his claims their lands. These terms were rejected, however negotiations between the two camps continued for three more years. Historians widely suspect that each kingdom was using the negotiations to stall for time to rearm and recuperate their losses.

Negotiations officially broke down in 1327, marking the beginning of the second phase of the Sixty Years' War. During the brief lapse in the conflict, the Ibbenian-Padanian alliance had managed to convince the Duke to Tolvas, the most powerful Toussaintain vassal to rebel. As per their agreement however the Duke would not turn his cloak until he had gained the King Louis' trust. As such, Duke Ramón of Tolvas invited Louis to a banquet in his honour where his armed guard brutally murdered the king and his entourage, plunging Toussaint into disarray. The death of the king was accompanied by a long string of victories for the Ibbenian league who were able to take much of northern and eastern Midrasia and were marching on Tolvas. Additionally, the Duke of Alpiens had chosen to make terms with the Ibbenians as he was facing religious and economic pressures back home. Nevertheless, the Toussaintian kingdom was held together by regent Eugène de Talourier who became guardian to the fourteen-year-old Francis, who was brother to Louis V. Throughout the two years of Francis' regency, Eugène played an integral role in holding the kingdom together, and a continued pivotal role in advising the new king, Francis IV following his coronation. Nevertheless, throughout the 1330s the Ibbenian League continued to make gains against the Toussaintians, with the aid of Piemontese rebels who had risen up against Francis. With the situation growing increasingly dire, and the League laying siege to Lotrič, the King and his court fled to Mydroll in 1341 in hopes of gathering an army to fend of the second siege of the city during the war. The city itself was on the brink of collapse throughout during the absence of the king, however the leadership of a peasant girl Amàlia d'Avant and the common effort of the city's inhabitants managed to fend off the siege. Efforts to combat the siege saw women joining the military in fending off assault attempts and smugglers using the Fiorentine sewers to sneak supplies and resources through the blockade. With the help of foreign mercenaries, Eugène and Francis were able to raise an army of 10,000 which advanced upon the besiegers the following year. The Ibbenians broke camp, retreating when word of the advancing army came. They were pursued to the town of Autun where one the most decisive battles of the war took place. Despite being slightly outnumbered, the tactical ability of mercenary commander Gawain Geddings proved vital to routing the opposing army, with the Tolvasians fleeing mid-way through the engagement, leaving the Padanian and Ibbenian armies to be annihilated. With news of this defeat reaching Ibbeny in 1342, a new truce was agreed, with both sides returning to the negotiating table. The negotiations would last nearly two years, during which time Toussaint was able to repay most of its mercenary debts and both sides rebuilt their forces. The Kingdom of Padania however had lost so many men throughout the war that their King, Clovis III refused to continue the fight, negotiating a separate peace through a payment of tribute to Toussaint. Padania however would soon be set upon by the rising Newreyan Kingdom within the following years due to its position of weakness. The Ibbenians and Tolvasians renewed their alliance in 1344, leading Toussaint to declare war once more, with the Duchy of Wallais also joining the conflict on the side of the Toussaintians.

The third phase of the war saw the Toussaintains once again gain the upper hand, winning a significant number of battles against the Ibbenian League. The Wallaisans also provided significant aid, mostly in the form of raids against Ibbenian farmlands, stealing crops and burning fields. Despite their upper hand in the war, discontent at home had reached an all time high, with dearth caused by the war significantly effecting grain harvests, along with the countless men who had died in the kingdom's war. As a result, a number of popular rebellions broke out across Toussaint, particularly within the regions surrounding the capital, marking the beginning of the Serfs' revolt. In spite of the issues at home, and the outcry of the nobility against the revolts, Francis was still able to inflict a devastating blow against the Ibbenians at the Battle of Parsonage, with the Ibbenian king, Henry IV slain in battle. With the death of the king and the general unrest in Ibbeny, the northern kingdom surrendered in 1355, recognising Francis as their liege lord and monarch. Nevertheless, the Duke of Tolvas vowed to fight on, with a number of former Ibbenian and Piemontese nobles flocking to his court. The continued resistance of Tolvas, which had suffered little comparative to the other combatants, ensured that the conflict would continue to drag on. Additionally, the Wallaisans had switched sides, allying with the Tolvasians after disagreements over the peace treaty with Ibbeny and significant bribes from Duke Ramón. Francis IV of Midrasia would utlimately die the following year, being succeeded by his son Philip. Despite some local resistance against Philip's accession in Ibbeny and Piemonte, these rebellions were quickly put down by the newly installed nobility, with harsh punishment for further dissidents. With the war continuing, efforts were made to take back Tolvas through an invasion of the Duchy. It was decided that a swift campaign to knock Tolvas out of the war as quickly as possible would be the most ideal tactic, and so the Toussaintian army advanced into the Veleazan lands in 1365. The force however was ambushed at Helios Pass and dealt a significant blow, preventing any invasion of Tolvas. The conflict continued until 1369 when fighting came to a stand-still as each side believed further campaigning to be fruitless. The subsequent peace treaty saw surrounding Asuran kingdoms recognise Philip's rule as King of the Mydra, whilst Philip would respect the independence of the Duchy of Tolvas.

Revolt of the Serfs

The Serfs' Revolt was an uprising of Midrasian and particularly Toussaintian serfs which took place between 1352 and 1353. The uprising saw thousands of serfs and free peasants rise up against local authorities and generally engaging in widespread rioting, destruction of property and the murder of royal officials and nobles. The revolt itself was caused by a number of factors, the majority of which related to the ongoing Sixty Years' War which had wrecked havoc upon the Midrasian countryside. The war had greatly affected harvests, with grain being requisitioned by the army and whatever was left being destroyed by the Ibbenian invaders, leaving very little for the local inhabitants. Additionally, large numbers of men had been pressed into service by their local lords, with many not returning, leaving a significant number of distraught widows and having a major effect on the collection of harvests. Furthermore, with the war having a significant financial impact, local landlords had been using their positions to extract increased taxation from their subjects, demanding higher rents from free peasants and higher harvest shared from their serfs. Many historians also contest that these issues had also been ongoing before the Sixty Years' War, with reports of abuse leading to a number of other local uprisings, such as the llodi Rebellion and Ypes uprisings during the Thirteenth-Century. Additionally, the little ice age of the Fourteenth-Century also had a discernible impact on crop yields, reducing the amount of food available to the peasantry.

The revolt itself broke out in the village of Vinsbourg in Toussaint where the local Baron, Tomàs de Valeri, had begun carrying out inspections of serf dwellings after reports of grain hoarding had come to light. Following these inspections, it was reported that the Baron was confiscating huge amounts of grain from each household, leaving the inhabitant without enough to last the winter. As news of this rumour spread, a number of serfs began rioting, breaking into the local barn stores gathering improvised weaponry in the form of pitchforks and other farming equipment. The serfs then stormed up the hill, breaking into the Baron's manor and slaughtering him and his guards. News of this revolt then spread throughout Toussaint, leading a number of other serf and peasant groups to take up arms, pulling down houses and stealing from their local lords. As the riots spread, the local nobility began to panic as most of their men were away fighting for the King in the war against the Ibbenian League. As a result, local gentry were forced to create makeshift militias from local retinues and peasants who had remained local. Attempts to negotiate with the mob were made in August, with Feliu Agut attempting to appease the rebellious serfs, however he was captured and hanged by the mob after he offered poor terms. Following this incident, the mob expanded, with a number of other towns and villages in Toussaint and the Rhone rising up, looting, pillaging, and murdering local lords. It has been suggested that the riotous mob numbered around 10,000 at its height.

By this point a man named Pep Porquet had come to lead the majority of the rebel forces. Pep had come to be known for his charismatic leadership skills and organisational skills. However, most historical depictions of him are actually drawn from Sylvain Gaudin's Seventeenth-Century play "Le roi et le Rebel" which depicts him as a swaggering, ignorant, proto-communistic tyrant. Nevertheless, many of the ideas put forward by Porquet can be seen as a form of proto-socialism, with the serf charter outlined by Porquet calling for the abolition of private hunting grounds and cattle, an end to enclosure, the right to elect local preachers and officials and a form of early overtime payment.

With the revolt making its way toward the capital of Lotrič, which was experiencing a number of minor uprisings, the nobility pleaded with Francis IV to take action against the rebels. After several months of negotiations and the pleading of the Mayor of Lotrič, the nobility demanded the king take action, or they would withdraw their forces from the war effort. The king relented, pledging a small force of 1,000 men to deal with the uprising and promising to establish an Assembly where landholders would be able to remonstrate against the actions of the king. The royalist forces met the rebels near Lereff, slaughtering the rebel forces on the spot. The severed heads of rebel leaders were also displayed within their localities to warn against future rebellion. Nevertheless, following the quelling of the rebellion, the King elected to remove several high officials for their roles in encouraging the outbreak of the revolt. Three local landholders were executed and serfdom was completely abolished within the kingdom in the hopes of quashing any further attempts at rebelling.

Midrasian Renaissance

The unification of Midrasia in 1309 had led to the creation of one of the most powerful polities on the Asuran continent, however the prolonged period of war had drained the country both financially and demographically. This issue was further exacerbated by the arrival of the bubonic plague only several years later. In response however, the kingdom underwent a considerable period of peace allowing it to rebuild and recover from the Sixty Years' War. As communities began to rebuild, economic prosperity soon returned, leading to the expansion of a number of guilds in key cities such as Lotrič, Bordieu and Argois. The most important of these guilds was the League of Argolis a confederation of various merchant guilds within the Asur Sea based in the city of Argois. The wealth of the league, in combination with its monopolising position allowed it to become the foremost trade power in the Asur, eclipsing the traditionally dominant trade cities of Riviera and Chalcia. It is believed by historians that this new emphasis on maritime trade spurred on a period known as the Midrasian Renaissance, lasting from around 1420 to the early 1700s with cultural influences from across the Asur breaking into Midrasia and leading to a number of developments in culture, religion, politics and science.

The most prominent of these new influences came from Chalcia and southern Aquidneck and mostly came in the form of Fiorentine and ancient Chalcian philosophical scripts and writings. Midrasian understanding of these topics was greatly enhanced by the arrival of a Chalcian philosopher known as La Chalca in 1432, who through his translation of Chalcian scripts into Fiorentine birthed a new wave of obsession with classical Chalcian philosophy. Nevertheless, this would soon be overshadowed by classical Fiorentine writings brought over from northern Majula and Arabekh leading to a new emphasis on classical philosophers such as Milonius and Caeso. This movement also greatly benefited from the invention of the printing press, allowing texts to be easily and cheaply reproduced, becoming accessible to larger sections of the population. It was out of these classical writings that a new movement known as renaissance humanism began to emerge, with scholars such as Fontané embodying a spirit of humanism, deeply ingrained within the traditions of ancient Fiorentina. This new philosophy was soon taken up by educational institutions across the kingdom, with the studia humanitatis becoming the basis of much of early modern Midrasian education, emphasising grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry and modal philosophy as the basis of civic life. This new movement ballooned into a wider cultural phenomenon, whereby artists began to pursue works ingrained in ancient philosophy, as opposed to the religious scholasticism that had dominated the Middle Ages. New works of art emphasised realism, earthly imagery and Fiorentine mythology as opposed to religious paintings; whilst architects began to experiment with Fiorentine revival buildings. All of this was underpinned by a new influx of knowledge brought in from overseas through maritime trade which brought great prosperity to the cities of the kingdom.

This new phenomenon also had a deep impact on religion, with many historians viewing the renaissance as the point at which the church lost its cultural hegemony. The exploration of these ideas saw classical pagan figures who had been shunned and sidelined by the church become mainstream figures, as opposed to traditional Alydian religious scholars. Additionally, the Alydian church also suffered in that humanism's emphasis on personal human capacity over faith in god led many to abandon their traditional devotions in the Orthodox Church, leading to a rise in religious textualism and personal interpretation. This would ultimately culminate in the religious reformations of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries which had divided the church, with the rise of Puritan Alydianism and Ksaiism in central Asura. Nevertheless, modern scholars dispute the fact that the church lost much of its power, pointing to how the Orthodox Church in many ways benefited and even tied itself to this newly burgeoning cultural movement. In many ways the church used patronage of artists to join the official church to classical scholasticism through magnificent works of fine art and architecture. These new forms of religious propaganda, along with the expansion of the Alydian church overseas considerable raised the prestige and power of the official church, even if its grip over individual worship had waned.

The rise of humanism across the Kingdom also brought with it a number of developments within the political scene which in many ways undermined the position of the monarchy, with many scholars believing the Midrasian cultural renaissance paved the way for the overthrow of the monarchy in 1624. Many political philosophers within the period became enamoured with the Fiorentine Republic, though scholars in the employ of monarchs would regularly only explore the period of Imperial Fiorentina. Perhaps the most pervasive idea throughout the Midrasian Renaissance was the suggestion that Midrasia and not Aquidneck was the true inheritor of the Fiorentine legacy and through its superior position in terms of economics, population and territory must naturally transform itself into the second coming of Fiorentina. As a result, efforts were made to Fiorentinise the kingdom, with the reintroduction of classical fiorentine as the language of state, adopting classical military and political institutions and expansion into territories formerly ruled by the empire. Additionally, many political scholars called for the adoption of classical fiorentine legislative bodies such as the Senate and Public Assemblies, suggesting democratic government to be the most virtuous and fair form of governance. Furthermore, scholars such as Raimon de Lodi even went as far as to suggest that the monarchy should be entirely removed, restoring the classical Fiorentine Republic. The belief that the monarchy should be overthrown however was not widespread and would be shunned and censored until the revival of the idea in the early 1600s.

In addition to the cultural, religious and political aspects of the renaissance the period also saw a number of scientific advances, brought about by a new understanding of the natural world and the application of the scientific method. Traditionally, within the middle ages and early modern period, a monopoly of knowledge was believed to have been held by classical and ecclesiastical philosophers. As a result it was believed that all knowledge in the world could be found within the writings of scholars such as Milonius or Saint Stephan de Molait. With the exploration of the New World and Majula, it became apparent that these philosophers could not have held such a monopoly, without understanding of the existence of such continents and their alien flora and fauna. In response new scientific approaches began to develop, emphasising empirical evidence. Through this new approach, historians trace the development of modern science, with scholars justifying their theses based upon sensory experience rather than the citation of classical authorities. As a result, university education began to move away from traditional medieval practices such as disputation and towards direct study through dissections and experimentation. Universities began to develop facilities directly dedicated to this new method, such as botanical gardens, with natural philosophy becoming one of the most important subjects in renaissance education. Furthermore, advances in astronomy were considerable throughout the period, with the development of galiocentrism dedicated to Midrasian astronomer Jean-Baptiste Allaire. Additionally, the invention of the telescope within the Seventeenth-Century allowed for the documentation of stars and other celestial objects.

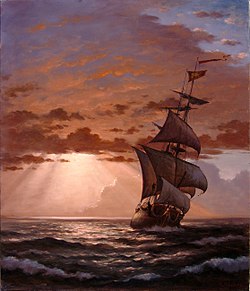

Prior to the Fifteenth Century trade between Catai and Asura had mostly taken place along land routes which historians refer to as the Jade Roads. These routes generally passed through the territory of the Volghari Khanate which ensured security and stability across these trade routes. With the collapse of the Khanate however, the Jade Roads became rife with banditry and fell into disuse, limiting the flow of goods between the two continents. It was this which was the impetus for the expansion of the League of Argolis throughout the Asur. With the dominant position of the league, Midrasia had established itself as a significant naval power within the Asur sea and well placed to exploit new sea routes. With a number of naval advancements such as the caravel allowing ships to travel much further distances, Midrasian explorers were able to charter routes down the Atlantic channel and Majulan coast, further south than any other Asuran vessel.

Naval ventures by other Asuran powers such as tir Lhaeraidd and Aquidneck leading to the discovery of Vestrim, or what at the time was believed to be Yidao led the Midrasian monarchy to sponsor a series or new naval missions to circumnavigate Majula and find a sea route east to Catai and Yidao. An Almiaroan explorer by the name of Delfino de Pallone was employed by the Kingdom to chart this route. Setting off in August 1496 with a fleet of five ships and a crew of 200 men, Pallone made landfall at modern Fortnouveau in February 1497, claiming the region for Midrasia. He then continued down the coast, making landfall at three other spots in southern and Eastern Majula were he was greeted by the local rulers. Historians suggest that when he was asked why he had come, Pallone responded: "Porteu-moi vostre aurum, et vostres Alydiens." (Bring me your gold, and your Alydians.). Following his departure from Majula, it is believed that Pallone's fleet continued up the Cataian coast until making landfall in modern Zhuodo in early 1498. During this time Pallone was received by the Yellow Emperor and remained at the imperial court for several weeks before making the return journey. Pallone made landfall back in Lotrič in mid 1499 with three ships and sixty men, having lost a number of ships to a storm and a significant number of his men to disease. Pallone received royal honours, a number of titles and a knighthood for his service in charting the sea route east; he also went on to document his travels in his writings which soon became a best seller among much of Asura, being the first chronicled journey to the east. Pallone's chartering of the sea route laid the foundations for Midrasia's overseas expansion with the Kingdom sending a number of other naval expeditions through the Atlantic Channel and towards Majula and Catai.

Whilst other Asuran powers looked west to Vestrim, the majority of Midrasia's naval expansion was focused south and east. Though a small number of naval missions were launched west, establishing several colonies in the Columbians, these missions were few and far between due to Aquidish tolls imposed on vessels travelling through the Strait of Troping. As a result, Midrasian missions west were forced to pay extortionate prices or sail around the southern tip of Arabekh. Therefore, the decision was taken to focus through the Atlantic Channel where Midrasia faced no such obstructions. Early missions saw the establishment of a number of outposts on the Arabekhi and Majulan coasts, allowing Midrasian merchants access to goods such as silks, spices and slaves. Due to the huge number of these outposts that were established in the wake of Pallone's charting of the eastern sea route, the crown reorganised these territories into the Estat d'Orient (State of the Orient) in 1502, to be governed by a Viceroy from the Port at Fortnouveau. The establishment of this new political entity saw a huge influx of south Asuran traders into Majula and leading to a huge expansion of naval activity within the region and the chartering of new missions east to Catai and Yidao. This rise in naval activity also precipitated domestic Midrasian expansion both militarily and territorially. A standing navy was officially established by royal decree in 1492 and was significantly expanded in subsequent decades. Additionally, measures were implemented demanding that ships unloading goods at harbours must fly the Midrasian ensign, effectively leading to the establishment of a merchant marine. Furthermore, military expansion into Riviera during the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries gave the Kingdom a number of new ports from which to operate, significantly improving Midrasia's naval capacity.

Arabekh, Majula and Catai were not the only continents Midrasia established trade links with, Rennekka was another important area of expansion for Midrasia, and a major driver of the Asuran slave trade. In 1505 Midrasian explorer Òscar de Xandri set off on an expedition from Midrasian to Brassida, circumnavigating Majula. However, on his journey he was hit by a storm and blown off course and is believed to have made landfall in the Mazarin Isles where several of his ships were wrecked. Following the island chain south, by 1506 Xandri eventually made landfall in Eastern Rennekka where he came into contact with the Moluche tribe. Records from Xandri's crew suggest the natives viewed the Midrasians as gods, touching their skin to feel if they were flesh and giving them gifts of fruits and gold. Xandri soon returned home to Midrasia with news of the newly discovered continent. King Henry III immediately dispatched new missions to survey and settle the new continent. Additionally Alydian missionaries were sent along to convert the local populace to the faith. News of the new continent of Rennekka spread like wildfire across Asura, leading a number of other states such as Veleaz to also establish colonies on its shores. The Midrasian kingdom established a number of settlements on the coast, laying the foundations for the colony of Renneque. Many of these settlements operated similarly to other Asuran colonies in Vestrim, relying on agricultural output of food and cash crops for their profitability. Nevertheless, significant stores of gold were also looted and mined from the territory by Midrasian conquistadors. Tales of these conquerors also led a number of Asurans to venture off to the continent in search of the mythical golden city of La Daurat which was fabled to exist somewhere beyond the continent's central desert.

Civil War

With the onset of the Seventeenth Century, the Midrasian Kingdom had diverged considerably from its medieval origins, with the growth of a new more professionalised monarchical bureaucracy through the sale of political titles, leading to a growth in the general power of the monarch themselves, along with the decline of the traditional landholding elite. This division between so-called noblesse de robe and noblesse d'épée created significant tensions within the governing structure of the kingdom itself, with significant clashes between the two camps playing out within the Noble Assembly. Additionally, the impact of the Midrasian Renaissance on religious and political thought had led to the growth in a number of groups posing a threat to the dominance of the monarchy. The most prominent of these being Puritan Alydian religious dissidents who existed in large numbers within the north and west of the country and advocates of Republicanism who held links with philosophers such as Augustine of Bordieu and Ksaiist preachers. Whilst these groups never received a direct public platform and were greatly persecuted by Midrasian authorities, they remained active underground and continued to hold sympathisers within the Noble Assembly, mostly among the more free-thinking humanist members of the Robe nobility.

The Seventeenth Century also coincided with the artistic zenith of the Midrasian monarchy, typified by the construction of a new royal court within the town of Roixs, complete with a royal palace which became the envy of monarchies across Asura. By requiring nobility and other governing personnel to move out of the capital of Lotrič to Roixs, the Midrasian monarchy had developed into a deeply personal form of rule, sometimes characterised as absolutist. As a result, the governing of the country became highly dependent upon the person of the monarch themselves and the loyalty of their intendants.

However, the death of Charles III in 1632 led to considerable instability within the kingdom, with his son Louis VII being too young to rule personally. Additionally, Charles' son was seen as considerably sickly with considerable doubt over his future health. As a result, Cardinal Duhamel became regent for the boy-king. Whilst Duhamel was expected to rule as a conscientious regent, greatly involving the Noble Assembly and regional Parlements in the governing of the kingdom, the Cardinal instead took upon a deeply personal rule, leading heavy accusations at Duhamel such as corruption, or the allegation that he was an alter rex. These allegations were exploited by a number of dissatisfied sword nobles who began to rally around Louis' uncle Prince Henry as an alternative candidate for the succession. Henry himself publically distanced himself from such calls, though secretly plotted with members of the nobility to intervene in the political situation which had been deepened by Midrasia's growing debts from colonial ventures and wars. In late November 1632, a session of the Estates General was called by Cardinal Duhamel, the first to take place in the Kingdom since the reign of Henry III. The session had been organised to find a solution to the Kingdom's growing debt and the issue of succession as Louis VII had been growing increasingly ill. Plans to relieve the debt through the increased sale of titles was voted down by members of the sword nobility who refused to allow more 'commoners' into the royal bureaucracy, whilst members of the robe nobility refused to give up their exemptions from direct taxation. The most divisive issue, however, was the demand by many sword nobles for Cardinal Duhamel to step down as regent in favour of Prince Henry. Duhamel had been characterised by the sword nobles as a puppet of the robe nobility, whilst allegations of corruption, sodomy and the perversion of the Alydian faith were also levelled at the cardinal. Following a vote on the proposals, the plot to depose Duhamel was defeated, leading many of the plot's sympathisers to walk out of the session and to later declare their intentions to see Henry installed as regent by force.

First Civil War (1633-1634)

The conflict erupted after a number of nobles across the country issued a joint ultimatum to Cardinal Duhamel to declare Henry as regent. This union labelled the League of Alpiens was primarily supported by the Dukes of Ibbeny, Riviera, Piemonte and Prince Henry who was currently serving as regent of Alpiens as an intendant of the king. Following a lengthy debate in parliament, the Midrasian regency decided to refuse the ultimatum and prepare for war. The League of Alpiens proved far better equipped for war, with most of their troops coming from noble levies as Midrasia still relied on its system of landholding retainers inherited from the medieval age. By contrast, the loyalist forces consisted only of a handful of troops held by petty nobles and the royal retinue stationed in the capital of Roixs. As such, the loyalists in parliament became heavily reliant upon mercenary forces for the bulk of their war effort, significantly denting the royal coffers.

Seeing the numbers not to be in their favour, loyalist forces deemed it necessary to go on the offensive, attempting to end the League's war effort before they could fully mobilise. The decision was taken to launch an invasion force at Monza, pacifying the Duke of Riviera, whilst sweeping up from the south to deal with Piemonte and Alpiens. Additionally, an attack from the south would prevent the League from making a direct attack on Roixs and Lotrič, buying the loyalists time. Despite this, the initial surprise invasion attempt was repulsed, forcing the loyalists to besiege the town of Monza. This prolonged siege allowed the League's troops valuable time to gather, launching their campaign in late April. The League's campaigns, however, were aimed firmly at taking the capital, rather than engaging the loyalist troops in Riviera. As such, these troops faced very little resistance before encountering the remainder of the loyalist forces stationed at Grisons. After a brief siege and battle, the League's forces triumphed allowing them to march on the capital unopposed. The King, Louis VII had been escorted out of the city of Mydroll. Nevertheless, the capture of Roixs led a considerable number of nobles who had previously backed the loyalists switched sides to support the League, proclaiming Prince Henry as regent of the Kingdom.

With the capital under lockdown, Henry dispatched troops to take Mydroll and King Louis. An attempt by the loyalists to smuggle King Louis out of Mydroll and to safety in Aquidneck was foiled by a local boatman who recognised the King and informed the local authorities. The King was soon detained and sent back to the capital in the custody of troops loyal to Prince Henry. Hearing this news, loyalist forces stationed on the march northwards after taking Monza became demoralised, hit with mass defections from its ranks. Fearing the worst, and with little gold to pay its mercenaries, the army made a last-ditch attempt to rescue King Louis by marching on Roixs. The army was met by Prince Henry's forces at the Rhone Valley where they were soundly defeated, Cardinal Duhamel surrendering to Prince Henry.

In the aftermath of the first phase of the war, the new regent Prince Henry set about purging those who had opposed his rule, starting with Cardinal Duhamel. Due to the influence of the Alydian church, it was unwise for Prince Henry to outright execute the Cardinal. Therefore, Henry chose to formally charge the Cardinal with treason and send him to the Pontiff in Laterna for punishment, along with a statement and request from the regent that the Pontiff deal with the unruly Cardinal, whilst also proclaiming his loyalty to the Alydian Pontiff. Numerous other loyalists were rounded up by Henry's supporters and either imprisoned or executed. A significant number of these either directly or indirectly had come from the Robe Nobility, leading Henry to give in to the demands of his aristocratic supporters in barring the robe nobles from the Noble Assembly and removing their exemption from direct taxation. Furthermore, Henry rewarded his loyal supporters with lands and titles confiscated from rebellious subjects. These measures made Henry wildly popular with the traditional landholding aristocratic classes, whilst earning the chagrin of many former robe nobles, many of whom had come from wealthy mercantile and gentry classes.

Despite his newfound popularity, Prince Henry's popularity soon began to fade as he was faced with the reality of the Kingdom's financial situation. Given the Kingdom's outstanding debts, and those taken on within the recent conflict, Henry was forced to increase the overall burden on his own subjects which furthered angered merchant classes who had just lost their tax exemptions. As the months progressed it was revealed by Henry's finance minister Abraham de Boudet that the situation was much worse than initially believed, leading Henry to request increased tribute from the nobility. Additionally, Henry relinquished into some of the demands of the mercantile classes, allowing the sale of new titles to raise revenue, whilst allowing small tax exemptions to encourage their purchase. These new measures also coincided with the death of King Louis VII in early April. Whilst official inquests suggested that the king had died from the flu, rumours abounded that Prince Henry had deliberately had the sickly king killed so he could inherit the throne himself. Historical opinion on the matter is divided, though what is known is that after the news was revealed, Henry declared his intention to succeed his cousin, to the delight of his supporters who proclaimed him Henry V.

Henry accession to the throne was met with opposition by the robe nobility who remonstrated against Henry's candidacy. An Estates-General was called to officially deal with the succession crisis in conjunction with the financial situation, though it quickly became clear that Henry was attempting to use the event as a legitimising tool, preventing any dissenting opinion from airing its concerns. When members of the opposition directly disrupted proceedings in order to speak up, Henry ordered the dissolution of the Estates General the following day, preventing those opposed to his rule as a political platform. This was soon followed by the attempted arrest of a number of opposition officials, notably Raphaël de Chaney, Évrard Saint-Yves and Jauffre Devreaux. Following this, members of the robe nobility gathered at the Lotrič Parlement to air their grievances. It was also declared that the Parlement would seek justice against the king for his actions. The declaration by parlement infuriated Henry who dissolved the body, declaring war on the institution and those involved in an alleged plot to depose him. This resulted in panic within the city, as bureaucrats scrambled to secure the safety of themselves and their families. Riots also began to erupt across Lotrič as rumours of further tax increases by the monarch began to spread. Finally, in September of 1634 a joint declaration of the Parlements of the land declared war upon the monarch, declaring their intentions to protect by force their ancient rights and liberties.

Second Civil War (1634-1642)

With the news of the Parlement's declaring war against the king and riots erupting across the capital; King Henry V deemed it necessary to flee Lotrič first to Roixs, and then to Bordeiu as rioting spread. Much of the nobility saw fit to follow the monarch, raising their levies and pledging loyalty to the sovereign. A significant chunk, however, mostly those within the vicinity of Lotrič chose to side with the Parlements for fear of their own positions. By 1635 a royal army had begun to gather in Bordeiu in support of the king, numbering some 60,000, greatly outnumbering the local guard of the parlements. In response, the Lotrič Parlement elected to enact an emergency ordinance dating back to the Serf's revolt which allowed it to levy a personal militia for acts of self-defence. Within several months of recruitment around the capital, the militia of the Parlement numbered some 30,000, though many of its members had been press-ganged into the force and lacked the necessary equipment and training to fend off against royalist forces.

Encouraged by their numerical advantage, royalist forces began their advance towards the capital in an effort to regain control of the situation. Though they were harassed by a number of militias, Henry's forces faced no significant resistance. Alarmed by the progress of the royalist camp, the Lotrič Parlement elected to send a portion of its forces to engage the encroaching army. Both armies met at Liege, and though the parlementary force managed to inflict a significant number of casualties on Henry's forces, its leader the Captain of Merport wound up dead, with the remaining force either retreating or scattering to the countryside. As news of the defeat reached Lotrič panic gripped the city. Believing certain defeat was inevitable, many parlementarians chose to flee Lotrič to pledge loyalty to King Henry. With the situation looking increasingly dire, the remaining members of the Lotrič Parlement chose that desperate measures were necessary. Calling upon ancient Fiorentine traditions, the parlement chose to appoint a minor noble and former general, Jauffre Devreux to the position of Consul, allowing him to effectively act as a dictator over the lands loyal to the Lotrič Parlement.

With the royalist force quickly approaching Lotrič, Devreux called for the construction of fortifications throughout the city and an increase of impressment into the military. Acts were also passed to re-conscript retired soldiers, whilst messages were sent to the Argois and Mydroll parlements for the conscription of a new force. Promises of payments and land for those who fought were also made in what historians see as the beginnings of the Nouveau Armeé.