History of Wazheganon

Evidence of human habitation in what is now Wazheganon dates back to at least 11,000 BCE. Archaeological records suggest that trade networks spanning the Kaċecameg basin and coast of Winivere Bay were common as early as 1000 BCE, with evidence of copper mined from northern Mousinë being found as far away as modern day Enyama and Serkonos in artifacts approximately dated to that period. Trade and travel along the Winivere coast was common, with many Wazhenaby peoples historically being culturally influenced by groups from as far as Elatia and Enyama. The peoples of what is now Wazheganon, the First Nations or Nebeseuweg (lit. "lake people"), were characterized to neighbors by their large canoes, extensive use of copper tools, and semi-domestication of megafauna such as muskoxen and forest mastodons. These advanced settlements frequently existed alongside non-agricultural semi-nomadic groups, and it was common for populations to move between these lifestyles throughout generations for a variety of reasons, including economic downturns, famine and other disasters, and dissatisfaction with leadership.

The first organized polities rose to prominence in the region around the early 8th century, believed to have been the earliest incarnations of the common mawaċimau model, in which extended families organize themselves into clans which democratically govern a band together based on consensus, which in turn confederate under popularly-selected councils, usually formed along linguistic lines. This early period saw the emergence of numerous polities, including the historiographically-termed Big Countries: confederations that were significantly larger than their more localized neighbors in population and area, made up of what are still today the largest indigenous ethnic groups in Wazheganon. These are the Masenatauq, Odoleqega, Hazirawi, and Onigamyg; the Wasöqwo, Nawymaiq, and Jajigaq are also often included among the Big Countries, although their remoteness from the Kaċecameg causes some scholars to exclude them from broad discussions of Wazhenaby history as a whole. Historically, the Big Countries have divided themselves into the Lakomkwe (a term derived from the Welasteyik word elakómkwik, "our relatives"), those which speak a Lakomic languages; and the Mayagi (Onigamymowin: foreign, exotic), the Hiwiran language-speaking Hazirawi and the Kayamucan language-speaking Odoleqega. These terms are extended to peoples outside modern Wazheganon by Nebeseuweg as well.

Mošógran period

By the early 11th century, the Hazira city-state of Mošógra rose to eclipse other polities in the Kaċecameg basin. Situated near the site of the modern city of Warasheq, Mošógra was well-positioned at the crossroads of trade between Winivere Bay, the Kaċecameg, and the northern forests. Part of the broad Mound builder tradition historically spanning Norumbia's east coast, the Mošógrans maintained dense urban centers with complex manufacturing economies, public works projects, and a ruling class of priests. Towards the middle of this period, Kaċecameg societies made the transition from copper metallurgy directly into iron and steel smithing, skipping the bronze stage historically common in other parts of the world. Through its trade networks and a system of ritualistic patronage, Mošógra maintained a system of tributaries as far west as Ataluca and as far north as Misiqwan. The city of Mošógra itself is believed to have been home to as many as 60,000 people at its zenith in the 14th century. Its extensive earthworks and ceremonial mounds still dot the landscape of western Wazheganon. It was through the Mošógran trade network that Onigamy syllabics, the predecessors to the modern Wazhewen syllabery, began to be adopted throughout the Kaċecameg basin. By the late 14th century, most of the Mošógrans' urban centers had been abandoned due to famine and plague, forcing urban inhabitants out into the countryside where they integrated with other tribes.

The height of Mošógra coincided with the first regular arrivals of Belisarian explorers in northeast Norumbia, whose early attempts at settlement, proselytization, and trade were stymied by indigenous warbands. Declaring Belisarians (or indeed any foreigners not from Norumbia) to be nebeunabeg, a sort of water sprite who came from the sea and were thus associated with evil underworld spirits, the ruling clergy used their network of patrons to organize warbands to systematically destroy Belisarian settlements and outposts on the east coast. This fostered a culture of deep mistrust towards any groups that were not recognizably indigenous Norumbians, and made regular contact and trade with those outside the Kaċecameg basin a rare and strenuous affair for centuries after the fall of the Mošógrans. The Ghantish Haratago settlements in modern Santa Elixabeta and Ternua are the only colonization projects to have survived this period, due to their relative remoteness and the inhospitality of their territory.

The decline of the Mošógran trade network and patronage system ushered in a power vacuum and dark age for many of the tribes throughout the Kaċecameg basin, triggering mass migrations and economic upheaval in many places due to the gradual destruction of supply chains. In the east, the collapse of demand for furs and iron led many Onigamyg to follow Belisarians eastwards across the Salacian Ocean. This eventually gave rise to the aazhawaasiwinineg (Onigamymowin for "the ones who are blown across by the wind"; often shorted to azhawineg), also called alaqtegetaq (Jajigaq'mawi: "the ones who sail about"), a seafaring subculture of numerous tribes on the northern and eastern coasts, which developed specialized warships with which they traded with and raided communities as far east and south as Vardana and the Nine Cousins as late as the 17th century. The Odoleqega took advantage of the power vacuum to expand their influence throughout the Oscandowa Mountains and east coast, becoming middlemen between surviving Belisarian outposts, the azhawineg, and more westerly tribes.

Akteweu period

The collapse of Mošógra caused many settlements throughout the Kaċecameg basin to revert back to the semi-nomadic, semi-agricultural hunter-gatherer lifestyle which had remained on the periphery of society since urbanization began, with the population fluctuating much more dramatically between seasons as entire cities dispersed in the winter months to supplement stored foodstuffs with game and forage. This era is called the Akteweu period (often just the Akteweu), from Masenomaweq for "the extinguishing of the flame", in reference the many hardships faced across the region during this time.

During this time, the Masenatauq became a major power in the Kaċecameg basin by serving as an entrepot between east-west trade routes. They also maintained a larger population than many surrounding tribes by leveraging the traditional harvesting of wild rice into an agricultural endeavor; similarly, the Odoleqega maintained a largely agricultural, urban lifestyle through the use of companion planting, which otherwise remained only supplementary in much of the region

By the mid-1500s, gunpowder weapons began to be introduced to the region. Historians disagree over which route gunpowder arrived by, though archaeological evidence suggests a slightly earlier arrival from the east to the Odoleqega and azhawineg via the Ghantarr and Ottonians. In any case, gunpowder quickly became the weapon of choice for many tribes and the Masenatauq and Odoleqega soon developed their own manufactories to produce and improve upon them. The matchlock arquebus fundamentally changed the military paradigm of the region, with archers, as well as infantry armed with steel clubs and axes, increasingly replaced by arquebusiers as time went on. This made the endemic warfare of the Kaċecameg tribes much deadlier, causing higher casualties which resulted in increased animosity and conflict. Eventually, this culminated in the Great Lake War, a vicious, prolonged conflict lasting from 1565-1593, which saw unprecedented mobilization and bloodshed among the Kaċecameg tribes. The war was further exacerbated by a plague, believed to have originated from Tsurushimese or Ottonian traders, as well as a drought-caused famine. Altogether, this period is believed to have led to the death of upwards of 20-30% of the population of the region. In the end, the Great Lake War proved inconclusive, with no clear winner. Many smaller tribes were completely wiped out as a result of disease and mourning wars, increasing the size and influence of the Big Countries who were better able to absorb losses.

Ottonian colonization

The Great Lake War dramatically weakened all parties and shattered traditional indigenous society in many places. The resulting economic downturn and shortage of warriors allowed Tyrrslyndic merchants and adventurers, who had for centuries been limited to minor trading outposts along the east coast, to seize territory from the Odoleqega and Masenatauq in the Oscandowa Wars from 1609-1624, ensuring a permanent, powerful position in the region. Forcefully resettling indigenous populations along the coast and in the Oscandowa Mountains, Tyrrslynd began colonizing the region with Kamryker settlers from Onneria, largely Protestants fleeing religious persecution in their homeland, who would come to be known as Umbiers. The sudden population movement further destabilized the region as large numbers of coastal tribes sought refuge and aid from more inland groups. All of this sent indigenous groups into further disarray and fanned flames of outrage and doubt. Among the Lakomkwe peoples, blame for the disastrous conflicts fell on the sagamores, traditional leaders whom were selected by their tribe but were hereditary by means of the division of labor created by the Lakomkwe clan system. The intergenerational failure of leadership to either obtain victory or secure peace earned the vitriol of their people, and led many tribes to abandon the traditional clan-based division of labor. Many groups put power in the hands of the clan mothers instead, effectively transitioning into matrilineal societies after thousands of years of predominantly patrilineal customs.

The eventual result of this upheaval was the Great Peace of Menawa, in which newly elected leaders from the Big Countries and 19 other tribes came together to absolve each other of past grievances in the interests of uniting against the Belisarian invaders. The diplomatic conference lasted for three months as old rivals struggled to reach a consensus. Terms were finally agreed upon, and then translated and written into many different languages, with the treaty being ratified by all parties on September 23rd, 1633. The treaty stipulated that, for as long as the Kaċecameg remained threatened by outsiders, their peoples would not fight, instead coordinating their resources to drive back the invaders. Disputes would be settled before a Paramount Council (Masenomaweq: māwackīketwan, literally "full debate/speech/word") which would meet anually in Menawa in the summer, and would attempt to mediate until a consensus could be reached; should this fail, disputing parties were to compete in a single decisive game of lacrosse where the winning side would get to enforce their demands. This system successfully would go on to successfully preserve peace between the tribes for over a century, coming to be colloquially known as "the League" or "the League of Menawa"/"Menawa League" (Masenomaweq: Wēcwētōhkameng Maenaewahgaang) in parlance with foreigners.

With internal conflicts set aside, in 1636 the Menawa League began an extensive campaign against the Tyrrslyndic colonists which would become known as the Ataluca War. Using a combination of guerrila tactics and deep penetrating raids into Tyrrslyndic territory, League forces' superior mobility in the forests and hills of the northern Osawanon Mountains ground the Tyrrslyndic advance to a halt. Without the obstacle of infighting and famine, the tribes of the League were generally a competent match against their opponents: while outnumbered due to their semi-nomadic history and without a reliable source of military animals (widespread adoption of horses only came in the mid-1700s, leaving most indigenous forces during this period with substandard moose or dogs, and the limited number of Onigamyg war mastodons were more of a psychological weapon than a practical one), the League's forest tactics and innovative experiments with flintlocks and mobile cannons allowed them to field a more maneuverable force with slightly more firepower than the Tyrrslynders'. The definitive turning point of the war was the Battle of Tewasaqy on August 15th, 1641, in which an approaching thunderstorm rallied League forces (who believed it was a legendary thunderbird coming to aid them in battle) and caused them to charge an army led by General Lotair Carden, which had been expecting no combat until the storm passed the next day, in the middle of the night in stormy conditions, catching them off-guard and supposedly driving many of them into the choppy waters of Lake Winogene. It is believed that this battle was the origin of the thunderbird as a universal symbol of indigenous Wazhenabyg.

Carden's force was almost completely destroyed in the surprise attack, dealing a crippling blow to the Tyrrslyndic offensive that resulted in a full retreat into the mountains by the spring of 1642, where Belisarian colonists had set up numerous stone fortifications in previous centuries as a precaution against raids. While small raiding bands were able to slip past Tyrrslyndic defenses, the bulk of League forces were forced into a stalemate due to a lack of heavy artillery suitable for assaulting heavily fortified positions in rough terrain. By April 29th, 1644, the Treaty of Aubishon was ratified, ending formal conflict between Tyrrslynd and the League and stipulating a rough border based on ridges and fortifications running through the Oscandowas and Osawanons that would become known as the Enyart Line. Although occasional border skirmishes would continue to flare up, the endemic warfare between the colonizers and indigenous population was mostly ended by this treaty.

The ending of major conflicts in eastern Wazheganon made increased trade and travel possible for both sides, and over time marriage between settlers and indigenous peoples became commonplace in the borderlands around the Mazhesepeu and Lake Ataluca. This eventually gave rise to the Mezhteg (singular: Mezhte, derived from Mëschtes, which is in turn derived from the Middle Kamryker word Gemëschted, mixed, and a cognate to Metis and Mestizo), a term broadly describing any person of mixed indigenous and Belisarian or Ochranese descent in Wazheganon. Historically, it was a flexible categorization that was used or ignored depending on the wealth and status of an individual, frequently depending on the status of their parents and/or the color of the skin. By the mid-1700s, Mezhteg would come to be the most numerous ethnic group in Wazheganon, and would begin to develop a distinct identity separate from their Umbier or indigenous origins that varied greatly depending on locale. Racial politicking meant that Mezhte rights were generally uncertain, and that they were frequently relegated to second-class citizenship among both indigenous and Belisarian populations. Despite their treatment, Mezhte groups represented a major cultural and economic link between Belisarian and indigenous groups that deterred further conflict. The Wazhewen creole langugage evolved out of the Mezhteg, an eclectic mixture of Masenomaweq, Onigamymowin, Jajigaq'mawi, Allamunnic, and Kamryker vocabulary and grammar which facilitated trade and communication in diverse communities throughout the Kaċecameg basin. The first written examples of Wazhewen come as early as 1653, and less than a century later it was the lingua franca of most of the region.

Valzian revolution and expansion

Officially designated as the East Norumbia Colonies, there were originally 8 distinct colonies, chartered by the Tyrrslyndic crown, in northeastern Norumbia: Nystalmark (now Nystolmarq), Nytyrrslynd (now Oscandowa), Maagdeland, and Sangweny, settled by Kamrykers, and Winnesauk, Moxaney, Squamsco, and Chebachipeg, settled by ostracized Ottonian pagans. They were later joined by the independent settlements of Santa Elixabeta and Ternua in 1629, who accepted Tyrrslyndic rule and taxes in exchange for protection from azhawineg raids, bringing the total to 10 colonies. The colonies historically enjoyed considerable autonomy from Tyrrslynd, and had little cultural or political sentimentality towards their metropole. Kamryker, a close relative of Sodden and direct ancestor of modern Umbiaans, or indigenous creoles were spoken in most contexts, with Allamunnic used primarily in dealings with the Tyrrslyndic Crown and military. The colonists, who traditionally identified themselves as Umbiers/Umbyreg (or Ombirag, later Gexabag, in the case of Ghantish settlers), maintained a strong tradition of local elections and self-governance, with most taxes levied by the Crown being put directly towards the infrastructure and defense of the colonies.

In the 1670s, the Colonies were a major participant in the Battle of the Salacian, a prolonged maritime conflict between Tyrrslynd and Ghant. While the Colonies incurred only minor losses compared to Tyrrslynd, the Norumbian theater saw heavy combat between Ghant-aligned indigenous forces (primarily northeastern Onigamy bands) and Umbier colonists. Tyrrslynd lost the war and, while it retained hold of its Norumbian territories, it suffered heavily. With the Tyrrslyndic navy devestated, Tyrrslynd was all but cut off entirely from its Norumbian colonies for several decades, during which time the Umbier tradition of self-governance grew much bolder and all-encompassing. Defense and taxation now became a continental matter, rather than one of the Crown, and the Umbier colonies began to see themselves more clearly as independent, autonomous entities from Tyrrslynd. By the early 1700s, Tyrrslyndic assets had recovered enough for the Crown to begin governing the Colonies once more, increasing its military presence and more aggressively enforcing policies in an attempt to curb Ghantish influence in the region, including limiting colonial expansion into the continental interior to garner favor with the Odoleqega and Masenatauq. However, the Tyrrslynders were forced to contend with both a restive populace that had grown fond of autonomy, as well as a critical lack of funds due to losses in the previous decades. Combined, this left Tyrrslyndic authorities largely helpless to enforce their rule and rendered the Colonies de facto independent. When the Jormundean Revolt erupted in Tyrrslynd in 1731, this status was solidified de jure as the colonies collectively declared their independence as ten separate sovereign countries. The ensuing Continental War was short and decisive, consisting mostly of a series of minor urban skirmishes with irregulars and a brief conventional campaign in the colonies' south. In most places, Loyalist forces were thoroughly routed by the Continentals and by 1733 the Treaty of Ardryk formally recognized the independence of all Tyrrslyndic possessions in Norumbia.

While each colony initially considered itself a sovereign country independent from its siblings, they rapidly coalesced into larger, unified entities in the interests of defense and the pooling of resources. The largely Protestant, Kamryker-speaking Nystalmark, Nytyrrslynd (which had been, in a fit of revolutionary fervor, renamed Oscandowa, after the Oscandowa Mountains), Maagdeland, and Sangweny quickly unified into the Federal Republic of Valzia. Gexabarag-speaking Santa Elixabeta and Ternua briefly partnered as the Republic of Gexaba, but soon chose to federate with Valzia as the difficulties of their geography and demographics in the face of independence became clear. The southern colonies of Winnesauk, Moxaney, Squamsco, and Chebachipeg, who were largely Ojihozoist company colonies which favored a monarchic form of government, would go on to found the Republic of Moxaney.

Independence resulted in increased investment in and immigration to the region as various powers took an interest in harnessing the potential of the new situation to counteract their rivals. This reignited and fueled more endemic warfare between Valzia and indigenous polities as Valzian settlers once again pushed into the Oscandowas and Osawanons. Northeastern Onigamy tribes aligned with Ghantish interests, with particularly strong bonds formed between azhawineg and Dakmooran privateers. The western Hazirawi and Wasöqwo frequently traded gifts and favors with Tsurushimese officials by way of the colony in Enyama. Tyrrslynd offered nominal support to the Masenatauq and Odoleqega in an effort to curtail Valzian expansion, while other Ottonian states favored Valzia for its anti-Tyrrslynder rhetoric. Latin investors took great interest in building up Valzia's maritime presence and expansionist ambitions as a way of creating a counterbalance against the Ghantish kingdoms. Competing foreign interests eventually led to the dissolution of the Menawa League in 1753, with the last meeting of the Paramount Council ending in violence between Onigamy and Odoleqe delegates.

Asherionic Wars

Expansion of Valzia and Moxaney into historically indigenous lands caused upheaval throughout the Kaċecameg basin, reminiscent of the first wave of expansion in the 1600s. Large numbers of settlers swept across the south of the country, supported by Belo-Mezhteg business owners who facilitated the economic domination of a now fractured indigenous and Mezhte population. This led to widespread resistance among local tribes who objected to the sale of their lands reinforced by Valzian banks and troops. By the year 1800, it is estimated that upwards of 50% of mawaċimau-controlled lands east of Hoshicyra on the southern side of Kaċecam had been appropriated piecemeal by private owners and the Valzian government. This led to further social and political turmoil among the major tribes. In particular, it gave rise to the Thunder Dance (Hazirat'e: Waką́čarawaši; Masenomaweq: Pakāhcekew Nīmwan; Onigamymowin: Animikii-niimiwag; Wazhewen: Dondernimen), a syncretic pan-indigenous belief system that originated in 1788 with the spiritual leader Hoshuwiga Krai (Hazirat'e: Hočųčųwįga Kaǧíra, "Woman-who-Fishes-in-Several-Places Crow"), a Hazira-Mezhte medicine woman of Tsurushimese descent. Hoshuwiga's Thunder Dance was a milleniarianist movement that encouraged specific rituals and unity among tribes, which would call forth the spirits of the dead and the mythical thunderbirds to help them in a climactic war that would banish "foreigners" (referring to virtually any group whose culture did not have its origins in that of the First Nations') and their influence from Norumbia, drawing on stories of the thunderbirds helping the Menawa League coalition at the Battle of Tewasaqy. The Thunder Dance quickly spread among tribes throughout the region, who syncretized its practices with their own, and drawing many to hear Hoshuwiga preach.

Among them was Asherion (Hazirat'e: Atejirehiga, "He-Who-Sets-the-Prairie-Grass-on-Fire-Suddenly-Like-Lightning"), a Benewak raised as a Hazira. A respected warrior, chief, and scholar, Asherion found success in rallying entire tribes to the mission of the Thunder Dance. Rapidly uniting the disparate peoples of the region, Asherion led a tribal coalition to victory at Göscugara in 1799, massacring Valzian troops in the aftermath, and going on to win a series of stunning victories that bewildered foreign observers. In summer of 1802, the Republic of Moxaney sent a substantial force at the request of Valzian Chancellor Pawel Lausser, considered a great humiliation at the time, only for a combined Valzian-Moxi force to be shattered at the Battle of Aubishon. Asherion's forces swiftly marched over the Oscandowas and secured the Valzian capital of Victorya on September 3rd, 1802, then proceeded south and overran Moxaney in unison with a massive indigenous uprising in the country's west. Asherion's strategic and tactical brilliance, combined with the use of mass conscription, intense drilling, combined arms assaults, and mobile artillery had overwhelmed and shattered the comparatively larger, better equipped Valzian army, much like the maneuver warfare and light cannons of the Menawa League had done to the Tyrrslynders 200 years prior. For his military genius and tactical innovations, Asherion is widely considered one of the greatest military commanders in world history, and the early 19th century of Norumbia would be defined by his campaigns, which bears his name as the Asherionic Wars.

Following the staggering victory, Asherion began to pivot the goals and message of the Thunder Dance movement; he crafted a pan-Norumbian, democratic, indigesocialist (in the tradition of the Zacapine and Talaharan revolutions) ideology with which to underpin his conquests, which would eventually come to be known as Asherionism. Asherionism called for a single, united federation of First Nations spanning the entirety of the Norumbian continent, firmly based in traditional usufructuary and direct democracy which could liberate all indigenous Norumbians. Asherion even went so far as to develop a constructed language based on many Norumbian language families, Hanunawe, with the intention of introducing it as an auxillary language for a new pan-Norumbian state, which he hoped would eventually lead to a single meta-ethnicity throughout the continent. Part of this project included the mass abduction of children from Belisarian-descended families (many of these families were recent arrivals, but some had also been present in Norumbia for nearly 500 years by this point), at which point they were entrusted to indigenous families, often of wounded or killed soldiers, and raised to follow indigenous culture and religion. For this policy, the Asherionic Wars are sometimes called the Last Mourning War. Private property was typically confiscated to community councils which were partially elected and partially overseen by appointed officials. Christianity was discouraged or suppressed as "a repressive, colonial frame of mind". Despite repressive stances towards Belisarians, Asherionic policies notably gave women and the poor the right to vote and participate in politics for the first time in many of these communities, and also allowed homosexual and transgender individuals to identify openly. This led to a phenomena in which the traditionally oppressed portions of society were disproportionately politically active under the new regime, and frequently favored by Asherion (himself speculated to have been asexual) and his officials.

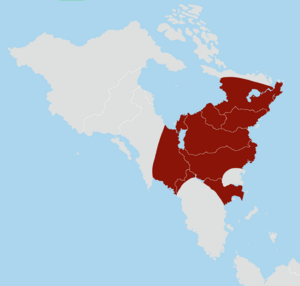

Declaring the Federative Republic of Great Norumbia (Hązírat'e: Hirosgijiranąga K’ijánįgijį́bìregi Hanųnačąk), Asherion set about reorganizing his conquered territories while calling for mass uprisings of mixed-race and indigenous peoples throughout the continent. Many observers denounced Asherion's rhetoric and policies, but little action was taken against Great Norumbia besides inconsistent economic sanctions. Beginning in the spring of 1805, Great Norumbian troops marched south, supported by popular and indigenous uprisings, and rapidly established a series of client states throughout northeast Norumbia which were soon absorbed into the federation as constituent states. Asherion stopped short of the border of Gristol and Serkonos, by now facing serious threats of retaliation from various camps. In 1807, Asherion invaded Serkonos and was surprised by the lack of mass support for his rhetoric, as the indigenous Serkonians had adopted Belisarian customs and economic restrictions for centuries by then. A united Gristolian-Serkonian force put up substantial resistance, culminating in the Great Fire of Donnaconna, in which the Serkonian capital was almost entirely destroyed and the combined army dispersed, reforming later in defense of the rump state that would come to be known as the Verkun Government. The invasion of Serkonos was an inflection point for the period, for the first time drawing in a coalition of states with the stated goal of containing Great Norumbia, with the Latin Empire (including its Belfrasian colonies), Gristol, Serkonos, and the Llahache and Anágan states of Tlaataaw, Ighai, and Dzillbesh pledging to liberate conquered territories and remove Asherion from power. Latium was immediately opposed by the Ghantish Empire, which sought a counterbalance to the Latin presence in Norumbia, and the Oxidentalese states of Sante Reze and Zacapican, which supported the pan-indigenous nature of Asherionism. Despite this substantial foreign support, the Oxidentalese counter-coalition was hindered by intense rivalry between its two members, whose navies often fought each other as frequently as the Latins. The sheer naval power of Great Norumbia's three allies was greatly appreciated, however, as the new country mostly lacked a formal navy or maritime tradition, primarily employing azhawineg privateers instead of than building and manning its own ships. This lack of naval assets allowed many governments in exile and rump states to take refuge on islands along the coast or escape south to Belfras.

In 1811, a Belfrasian counter-offensive began pushing into central Gristol but was eventually forced back behind the Canotou River in the south of the country, leading to a standstill on Great Norumbia's southern front. In the west, Llahache cavalry swept into Serkonos and created a dynamic, highly mobile war which Asherion largely ignored while focusing on the more existential Belfrasian threat. In 1814, republican, Asherionist uprisings throughout the Sunset Coast led to a collapse of the western front as forces were recalled to support or suppress the revolutions, allowing a swift Great Norumbian advance into the western desert, which was complicated by the stretching of supply lines, lack of experience in desert warfare, and the chaotic diplomatic web of dozens of states in upheaval. Geography also limited Asherion's options on the southern front, where the Allghene Mountains, Thenchuse Heights, and rainforests of Mondria promised a long, grueling campaign where his forces, of mostly northern origin, would be decidedly out of their element. However, before he could commit to a long-term campaign in the west, Asherion knew that the last Belisarian foothold on the continent, Belfras, must be dealt with. In the summer of 1817, Great Norumbia broke through the Belfrasian defensive line and began advancing south. The offensive was slow and brutal, with many Great Norumbian forces dying of exposure and disease, until the campaign was definitively stopped at the River Tebe in 1821, having advanced less than 300 kilometers from its starting point, with the situation rapidly deteriorating. In March 1822, Asherion himself was captured in battle and handed over to Latin authorities.

The Great Norumbian front crumpled following the loss of its most brilliant general and rallying figure and Belo-Norumbian guerrillas crippled the war effort in many areas. A coalition tribunal determined to exile Asherion to the Imbrosian Islands, rather than risk triggering further uprisings by martyring him via execution. The ship transporting him was captured by the Rezese while restocking on the island of Silurum, who then redirected him back to Valzia. He proceeded to rally the swiftly collapsing republic in a final series of clashes in northern Gristol, but the exhausted populace was unable to rally a substantial force to counteract the momentum of the coalition. At the Second Battle of Pontiac-Bernadotte in November 1822, Asherion was captured once again and prevented from falling on his own saber. In a diplomatic agreement with Sante Reze to bring the conflict to a close, Asherion was granted adoption into House Cardiki and accompanying property, but simply used his new means to flee the country and once again attempt to rally Great Norumbia. The result was an anemic rebellion in the hinterlands of western Valzia which was quickly crushed. Exasperated , the coalition reached an agreement with Zacapican in which Asherion would be given a military position in Oxidentale, thereby being unable to return to Norumbia without dishonorably abandoning his post. Asherion spent the rest of his life in the service of the Red Banner Tribunal, commanding forces in Zacapine Araucania and fighting in the Second Araucan War. Asherion died in his sleep in 1839 at the age of 68, and his body was interred in a monument built in the town square of Amegatlan, Zacapican, until 1926, when his remains were transferred to Keshaq, Waushyra, in Wazheganon, and interred in a mausoleum near the site of the settlement he was originally from.

Waltzing Coups period

Following the collapse of Grand Norumbia, its client states were liberated and reorganized according to the Congress of Thessalona. Valzia was given sovereignty over substantial territory to the west of the Oscandowas that it had only nominally controlled previously, developing a southern border along largely physical boundaries that encompassed the historical lands of the Odoleqega, Masenatauq, and Hazirawi. The humiliating defeats and occupations of the Asherionic Wars had embittered the Valzians and in retaliation they imposed widespread restrictions on the political, civil, and economic freedoms of the First Nations now under their control. Although guerilla resistance became endemic, most indigenous groups had been too drained by over twenty years of warfare to resist these measures as they were implemented. Indigenous people and Mezhteg of non-Belisarian appearance or who openly practiced indigenous customs were entrapped into a racially discriminatory system, the institutions of which would secure minority rule for white Umbiers, legally for nearly a century, and de facto until 1976.

This led to a land grab in which the community-owned enterprises of indigenous populations were suppressed and commonly-owned land was systematically divided and sold on a scale which dwarfed the previous era of 18th century expansion. Speculators and investors from the east coast quickly made inroads, turning huge profits by exploiting groups which had few legal protections and lands which had until now been carefully stewarded and selectively used. Industrial and business interests came to dominate Valzian politics by the 1830s, with a duopoly of the Centralist Party (supported primarily by urban industrial and military interests) and National Party (sustained by rural ranching and mining interests), whose policies differed primarily in superficial foreign policy (such as whether to support Ghant or Latium in any given affair), allowing them to cooperate in solidifying control over the economy and federal politics. However, despite shrewd stoking of racial tensions and fear-mongering over the economy and foreign threats, the duopoly was threatened by the liberal Liberal Democratic Party and socialist Workingmen's Party, who advocated for reform and enfranchisement.

As these smaller parties agitated for voting reform and indigenous rights, the election of 1836 proved one of the most contentious in Valzian history up to that point. National Party candidate Augustyn Delaglys, a former military general during the Asherionic Wars who had become a rancher in the commonwealth of Jenasha and a popular hero amongst the Umbiers for his performance at the Second Battle of Pontiac-Bernadotte, was defeated by a slim margin by Centralist Party candidate Mathias Gault, a Nydonmer businessman from the Centralists' liberal wing who had risen to prominence on promises of voting reform. Calling upon his military and business connections, Delaglys staged a largely bloodless coup on the night of July 13th, 1836, just two weeks after Gault's swearing in, taking control of the government under the auspices of "defending the Republic from Asherionic subversion". Although there was some confusion in the following weeks, Delaglys's actions were ultimately endorsed by both the Centralist and National Parties, who afforded him emergency powers to combat the (largely fabricated) threat of indigenous and socialist revolution. Delaglys's personal popularity stymied public backlash, which was quelled altogether, later that September, when Delaglys enacted a decree which granted suffrage to all males 18 years and older regardless of wealth or property ownership, notably explicitly excluding those of indigenous descent or who were "hereditarily predisposed to anti-republican tendencies". This wildly popular move secured Delaglys's position through a referendum the next year, and gave him room to begin suppressing socialist and liberal elements.

This marked the beginning of the Waltzing Coups period (Umbiaans: Walsenstaatsgreeps), which was characterized by a series of strongman dictators who came to power primarily through coup d'états, either forcefully via the military or through soft coups arranged by military and business interests, usually organized at extravagant galas whence the period gets its name, and then confirmed by plebiscite or electoral fraud shortly after.

In order to further redirect public attention from the erosion of Valzia's democracy and the centralization of its wealth by business interests, Delaglys began a series of military campaigns against the northern Onigamyg and Nawymaiq that would become known as the Northern Wars (Umbiaans: Noordelike Oorloë), or Totem Wars (Onigamymowin: Niidoodem-miigaadiwinan), in which various northern bands were systematically isolated and conquered. These conflicts continued and were expanded upon by his successors, namely the annexation of the independent, primarily Wasöqwo Confederation of Hyċeqoy in 1854 by Nicola Jacoby, and the conquest of the Nawymaiq Misiqwan Republic by Olivier Gyger in 1882. Despite severe repression and the imposition of the Valzian political-economic system, indigenous identity remained strong in most places and the Mezhte population ballooned throughout the 19th century as economic and personal realities overcame cultural prejudices and systemic racism.

The Waltzing Coups period also saw the meteoric rise of socialist organizations throughout Valzia as the country industrialized, particularly syndicalist industrial unions of miners and factory workers advocating for a return to democracy and democratization of the economy, as well as indigesocialist activists advocating for land reform and ethnic autonomy. Socialist militias frequently clashed in pitched battles with the federal military and private corporate forces, such as the Battle of Opvalmberg in 1884 which left nearly a hundred dead on both sides.

Democratic elections were reintroduced to Valzia in 1895. Chancellor Olivier Gyger, having suffered a stroke in 1884, had nominally retained his office but in practice delegated almost all of his duties to his long-time romantic companion Minerva Nients. Nients was a beloved popular figure throughout the country and champion of labor rights and women's suffrage, as well as a shrewd stateswoman. She announced Gyger's resignation on February 3rd, 1885, and formally took the chancellorship for herself with popular acclaim as the first female chancellor of Valzia. Military and business interests attempted to threaten and remove her, but dared not risk a mass uprising by her supporters. Nients soon set about removing corrupt officials and reforming laws, legalizing women's suffrage in 1887. She announced her own resignation just a decade later 1895, resurrecting the tradition of ten-year terms for chancellors, and oversaw the first free and fair election in Valzia since 1836, with Nicolas Grauw of the Liberal Democratic Party taking office that July. The next congressional elections saw the collapse of the National Party as it lost support to socialist parties, merging with the Liberal Democratic Party to form the National Liberal Party in 1887. The Centralist Party soon dissolved and reemerged as the Constitutional Party in 1889. Leftist parties such as the Farmer-Labor Party, an unusual alliance of trade unionists and social democrats, and the big-tent Socialist Party, became serious competitors at a federal level but failed to capture the chancellorship because of ideological infighting.

Wazhenaby Federal Socialist Republic

Despite the major victory for liberals and socialists, the national economic situation remained largely the same. Workers' rights and the dominance of corporate monopolies remained serious issues. While many of the explicitly oppressive Delaglysian policies of the Waltzing Coups era had been rolled back, indigenous and Mezhte rights were still in an abysmal state, and calls for land reform and autonomy were frequently sidelined by Belo-Socialists calling for class to be the main focus of their programs. In the period from 1895 to 1919, socialist and anarchist groups went about building significant subversive power structures throughout the country, with unions and community organizations gradually replacing state institutions in many parts of the country. The short-lived Ponoka Valley War of 1901-1904, in which disputes between cattle ranchers along the Awasi border escalated into military skirmishes, was resolved diplomatically in part due to the influence of anti-war Leftist factions in Valzian politics which had been suppressed for decades before 1885. These unresolved tensions came to a head in February 1919 with the assassination of Chancellor Arnold Brent by the anarchist Pascal Okwalihaqa, which triggered a crackdown on Leftist political elements spearheaded by the Constitutional Party, in turn causing first a general strike, and then many Leftist organizations to openly rebel against the Valzian government, beginning the Valzian Civil War.

While the war was nominally between the Loyalists (supporters of the federal government) and the Revolutionaries, both groups were generally broad coalitions. The Loyalists, estimated to have been supported by 20-30% of the population at the time, were a primarily Umbier faction on the east and west coasts which ranged from run-of-the-mill liberals, to Delaglysian authoritarians, proto-Invictist Vyrkantists. Assuming emergency powers which allowed him to suspend elections and congressional powers, General Frederic Lux spearheaded the crackdown on mass uprisings throughout the country, utilizing both federal troops and Vyrkantist militias to reinstate federal control. While the Federal Salvation Government (FHR, Federales Heilregering) led by Lux and remnants of the federal government was technically the only de jure belligerent on the Loyalist side of the conflict, the Loyalists also consisted of numerous military cliques and militias which nominally served under the FHR. Chief among these were the Free Army of the Hesepuq, which advocated for a formal return to the stratocratic authoritarianism of the Waltzing Coups in order to protect democracy, and the Aitzema Brigade, an autonomous Vyrkantist paramilitary in the southeast led by Aris Aitzema which called for ethnic cleansing of Mezthe and indigenous populations. Despite their stated goals of restoring the republic, many of these paramilitaries and cliques frequently engaged in skirmishes with both federal troops and each other as well as against the Revolutionaries, frequently pledging allegiance to military officers over Lux or the Republic.

The Revolutionaries, meanwhile, were a fractious coalition of socialists, anarchists, syndicalists, and indigenous nationalists, largely lacking a common banner. The All-Valzia Industrial Union (AWIW, Alwalzye Industryelwakbond), whose steering committee was chaired by eventual chancellor Haiko Woskes at the time, was the most prominent Leftist organization at the beginning of the war, with approximately 6 million registered members out of a national population of about 20 million; the AWIW took the lead in organizing the military side of the uprising, fielding the first large-scale, organized military units of the Revolutionaries. As time went on, the Jabwegan Revolutionary Council (JRR, Jabwegen Rewolutyerraad), chaired by Tatyana Jung, who would later go on to be the second female chancellor in the country's history, became the preeminent Leftist faction; situated in the industrial heartland on the Meshgoseq-Jenasha border and incorporating anarchist and indigenous organizations, the JRR quickly gained support throughout the country's south. On the east coast and upper Mazhesepeu region, Gethsemanite congregations, the bulwark of the Christian Worker Movement, spearheaded the organization of the Radical Liberation Synod (RBS, "RadSin",Radicales Bewryding Sinod), an alliance of churches and Christian anarchist organizations, as well as Jewish anarchists and radical Midewiwin lodges, which protected minority communities, distributed aid for communities impacted by the war, and engaged in some of the fiercest fighting of the war against Vyrkantist paramilitaries in Oscandowa and Mägdeland. Eventually, the AWIW, JRR, and RBS, along with several other smaller organizations, would unite under the Revolutionary Committee for the New Valzia (RKNW, ReKNeu, Rewolutyerkomity jou Neuwalzye) in September 1919. Meanwhile, indigenous nationalists and anarchists throughout the west and north of the country gradually coalesced under the banner of the Seventh Fire Front (ZWF, Zewende Wür Front).

The civil war consisted of two phases. The first phase, from February 1919 to September 1920, consisted of the crumbling of the FHR in the face of increasingly overwhelming popular support for the Revolutionaries, and the mass exodus of some 300,000 Loyalists from the country as a result of mass property seizures, democratization of firms, and, in some regions, revolutionary terror. Some Loyalists who lacked the means to leave the country, or otherwise refused to do so, reorganized around the National Radical League, a nationalist-ordosocialist organization. Generally speaking, most Valzians at the time were sympathetic to Revolutionary cause for either ethnic or community reasons, if not ideological ones, and control of the industrial and agricultural heartlands allowed the Revolutionaries to redistribute aid to areas impacted by the war, winning them popular support with otherwise neutral groups. By contrast, the largely status quo antebellum rhetoric of the Loyalists, at times exacerbated by the ultranationalism of the Umbier Vyrkantists, attracted little support outside of Umbier communities and petty bourgeois Mezhte groups. The second phase of the civil war, from September 1920 to July 1921, consisted mostly of fighting between Revolutionary factions. By this point, the ZWF had seized control in much of the north and west of Valzia and were staged to divide the country into multiple rump states. Conservative and libertarian factions disagreed on how to address this issue; the conservatives wanted to forcefully bring ZWF-occupied territories back into the fold to prevent a weakened Valzia from being targeted by counter-revolutionary neighbors, while libertarians believed the ZWF should be allowed to secede and could be peacefully reintegrated later once the chaos of war and nation-building had subsided. The two factions entered into open conflict in ZWF territory, but only rarely fought in territory already controlled by the RKNW, and by the summer of 1921, ZWF resistance had been crushed and the conservatives had cemented their ideological dominance. On July 8th 1921, just ten years shy of the country's bicentennial, the RKNW declared the creation of the Wazhenaby Federal Socialist Republic (WFSR), deriving a new name for the country from a historical Mezhte term for the eastern part of the country: Wauzhagigän (ᐗuᔕᑭᑲᓐ), anglicized as Wazheganon.

Concurrent with and following the Valzian Civil War was the First Osawanon War, in which the Moxi province of Bewenak revolted with RKNW assistance and joined the newly formed WFSR as a constituent commonwealth. The first stages of the Bewenak rebellion began in earnest in May 1919, inspired by the labor and indigenous uprisings to the north, but the lack of major political or labor organizations in Bewenak made a coordinated revolution challenging, causing the rebellion to stall in a guerrilla war between the Moxi military and rural paramilitaries comprised of both Leftists and indigenous nationalists. In the the spring of 1921, Wazhenaby forces formally entered the conflict after two years of cross-border skirmishes and providing refuge for Bewenak guerillas, striking at both Bewenak and Moxaney proper and beginning a war of attrition in the Osawanon Mountains and urbanized coast which would last until 1924. In addition to Wazhenaby and Moxi forces, expeditionary forces from Gristol-Serkonos, Awasin, and the government-in-exile FHR opposed the rebels and Wazhenabyg. The combined civilian and military death toll of the Valzian Civil War and First Osawanon War is estimated to be anywhere from 300,000 to 800,000. Many supporters of the old government who could not or refused to flee the country eventually reconstituted into the National Radical League, a nationalist ordosocialist group.

Following the end of the Valzian Civil War, Tatyana Jung, chairwoman of the JRR, was elected as chancellor of the new republic and called for an ambitious series of economic and social reforms. The official language used by the federal government was changed from Umbiaans to Wazhewen, which was spoken by the vast majority of of the population compared to Umbiaans's presence on just the east coast, and individual commonwealths were encouraged to name their own regional languages for official use. Homosexuality and transgender identity, long accepted by most indigenous and Mezhte communities but persecuted under Valzian law, were decriminalized, as were abortion and divorce. In keeping with the conservative realignment of the RKNW-ZWF conflict, most major firms were nationalized and their management and coordination entrusted to a combination of regional labor councils and federal oversight committees. Major construction projects under the Western Plan promised to bring economic development and better quality of life to the sparsely developed western commonwealths, but in practice tended to alienate and displace indigenous populations who simply wished for autonomy over their communities and land. A national standard for urban planning was introduced as cities rebuilt and expanded following the war; colloquially called "Ana streets" (Anastrateg), these dense, community-oriented, public transport-centered projects continue to serve as inspiration for Wazhenaby cities in modern times. The federal capital was moved from Victorya to its modern location in Moynrout, symbolically moving political power out of the Umbier heartland and towards Mezhte and indigenous groups.

In 1927, Wazheganon entered into a series of conflicts with Ghant in the Sea of Dakmoor that would come to be called the Cod War. Originally beginning with minor quarrels between Ghantish and Wazhenaby fishermen over plentiful fishing territory, it eventually escalated into armed fishermen's militias firing upon each other at sea, which prompted the involvement of proper naval forces, although, due to the structure of each country's government, the conflict was primarily between Wazheganon's northeastern commonwealths and the Ghantish kingdom of Dakmoor. The conflict remained primarily between heavily armed fishermen's militias for most of the 1930s, with skirmishes involving boardings, machine gun fire, and even aerial strafing becoming common. Raids and arson attacks on the harbors in Goeporta and Granbaya inflamed tensions, and in 1935, with the beginning of the Great Ottonian War, Wazheganon formally entered that conflict on the side of North Ottonia, opening a periphery front against Ghant in the Sea of Dakmoor and northern Salacian Ocean, while Ghant itself became embroiled in civil war, the Mad Emperor's War. Dakmoor, the northeastern commonwealths' principle opponent in the Cod War, was invaded and its leadership executed by Emperor Nathan III. Now in an active state of war with the Empire of Ghant, Wazheganon seized the opportunity to stage an ambitious amphibious invasion of Dakmoor in 1936, and soon found themselves fighting alongside the same militias and nobles they had previously been fighting against in the Cod War. The Wazhenaby Expeditionary Force, Dakmoor (WEM, Dagmör) numbered approximately 7,000 personnel, sourced from both the Federal Armed Forces and myriad militias, and fought throughout Dakmoor and western Ghant in support of anti-monarchy, Leftist subfactions opposed to Nathan III, especially the People's Liberation Front. 362 Wazhenabyg from WEM, Dagmör would die from a combination of exposure, disease, and combat by their withdrawal in 1940, with an approximate further 500 injured, a casualty rate of 12%. By 1940, the Mad Emperor had been killed and most of Ghant had been reconstituted under the government of Emperor Michael I and Prime Minister Malderi Haribec. In Belisaria, the Great Ottonian War dragged on without Ghant, allowing Wazheganon to send what meager materiel and troops it could until that war's end in 1943. Ingratiated to the Dakmooran nobility for their military efforts, despite their motivations, and sharing political sympathies with Haribec, the Wazhenabyg were able to secure a mutually beneficial treaty amending fishing rights and territorial waters in the Sea of Dakmoor, ending the Cod War as well. Most of this period was presided over by the administration of Ijan Otaqua (1931-41), the first indigenous chancellor in the country's history, who is remembered for his progressive cultural policies but also for the largely unpopular intervention in Ghant.

Anouwälist renewal

Despite the general popularity of the administrations in the decades following the revolution, dissatisfaction among indigenous and affiliated Mezhte communities led to frequent agitation. In particular, the Seventh Fire Front was reconstituted as a clandestine terrorist organization, primarily in the western commonwealths, which targeted government facilities and Umbier (or what they perceived as Umbier-derived) cultural institutions, demanding the returning of land to indigenous groups and a terminal decentralization of the country's politics in line with the historical mawaċimauweg model. Once more, indigenous nationalists found common cause with the ultraleft. The AWIW had remained active following the civil war and served as a parallel economic structure to the federal government, and, with many of its members dissatisfied with the centralized turn the country had taken, frequently participated in strike action, slowdowns, and other protests in support of the ZWF's goals. The federal government often struggled to implement its largely centralized, planned economic schemes in the face of large, critical swaths of the economy shutting down or redistributing resources elsewhere independently. This reached a tipping point in 1955, when the administration of Jan Morgan attempted to outlaw wildcat strikes and bring the AWIW into line with federal objectives.

This triggered the first general strike in Wazheganon since the end of the civil war, with an estimated 12,000,000 Wazhenabyg participating. The AWIW demanded a constitutional convention which would allow for debate and restructuring of the fundamental aspects of the republic's government and economy. Fearing the possibility of a civil war, the Morgan administration readily agreed. Lasting well into 1957, the convention saw the rising popularity of the ideas of Awyn Anouwäl, an electrician serving as a representative from Latulita. Influenced by the principles of indigenous mawaċimauweg and the Radical Liberation Synod, Anouwäl and his supporters proposed a system similar to the council republics popular during the civil war, in which neighborhood councils confederated together to form autonomous, large-scale governments. Eventually codified as Anouwälism, or libertarian municipalism, this model would serve as the basis for the new Wazhenabyg federal structure which largely persists to this day. These reforms were overseen primarily by the interim administration of Chancellor Rïntsye Ragaby, a friend and student of Anouwäl. The presidential system used since the country's founding in 1731 was replaced with the modern directorial system, in which the chancellor is appointed by Congress and serves primarily as a secretary and presiding officer for a steering committee, in addition to being the de facto head of state in conducting official visits abroad. While the federal government retained some means of indicative and central planning, most of the economy reoriented around decentralized planning and mutual aid, similar to the modern system. Conscription was outlawed, and the justice system was reformed to be more restorative.

The Emergency to present

Decentralization was rapid, and the new system's popularity was greatly bolstered by the autonomy it afforded to indigenous communities. However, standards of living between the western and eastern halves of the country, and especially between indigenous and Umbier regions, remained a blot on Wazhenaby socialism's reputation. Over the next two decades, numerous programs and ideas were explored to elevate indigenous communities, but the implementation of economic justice and land reform was largely frustrated by conservative elements, especially the National Radical League, who claimed that reparations to First Nations and Mezhteg and promotion of their autonomy was in fact racist and oppressive towards other groups, and deemed the concept incompatible with the materialist worldview they held necessary for socialist ideology. Fear-mongering about the ZWF and fabricated conspiracies around indigenous rights policies (such as the notion that non-indigenous individuals would be barred from participating in politics, or that non-indigenous inhabitants of traditionally indigenous land would be victims of state-sponsored genocides) allowed the NRL to eke out a sizable minority among the conservative parties of the era. Even so, discourse continued and by the early 1970s strides were being made in this area, despite its divisive nature. This came to a head on December 24th, 1975. An extended session of congress remained in session despite the holidays, with Chancellor Andre Borell intent on bringing an economic justice and land reform bill to vote before the end of the year, and on the evening of that Christmas Eve an explosion occurred on the floor of Congress, killing 231 of 334 representatives and injuring dozens of others. With Borell being killed in the blast, the surviving members of Congress and the General Committee appointed Secretary of Defense Octavya Laberenz as temporary Acting Chancellor.

Laberenz, a former member of NRL who had since identified with the All-Socialist Front, immediately began a crackdown on suspected ZWF elements, which included the mass incarceration of indigenous and Mezhteg politicians, academics, and activists using the federal military and NRL paramilitaries, with apparent plans to begin gathering entire populations into concentration camps to later be dispersed and resettled. This marked the beginning of what is known today as the Emergency, the Wazhenaby Spring, and the Decemberist or Laberenzite Putsch. Laberenz's commands were immediately met with outrage and large portions of the military refused to follow through with the orders, and a general strike was soon called. It would eventually be revealed through recovered documents and testimony that Laberenz, with the aid of elements of the military and intelligence community (with her supporters and collaborators being broadly referred to as Laberenzites or Decemberists), had been behind the Christmas Eve bombing, and had prematurely launched her coup attempt out of fear of being unable to reverse the reparations package once it had been in effect for too long. This premature action meant that many NRL officials and military units loyal to Laberenz had not yet been appointed to their intended strategic positions; this mostly prevented the Laberenzites from cutting electricity from large population centers, shutting down major railways and roads, and seizing control of radio and television broadcasters, meaning that the population at large was able to react to the coup in real time. Combined, this meant that the coup was largely dead in the water by the first week of January 1976.

While the coup was a strategic failure, large pockets of Laberenzite militia and military forces remained wedged in urban centers and major logistical hubs, including the capital in Moynrout. Faced with ostracization and arrest, most units chose fortify their positions and hold out as long, or do as much damage, as possible, although some also chose to try and escape across the border into Moxaney. The result was a months long quasi-civil war in which hundreds of thousands of Wazhenaby citizens engaged in mass social defense against Laberenzite forces in the streets of major cities, essentially hostages fighting back against their captors; meanwhile, the anti-coup forces in the federal military spent much of the period in a mobile campaign trying to prevent mass murder of minorities by rogue militias and the destruction of important infrastructure which would kill many more, while preventing the movement of the more entrenched forces. Notable among these incidents were the attempted destruction of Taċipesta Dam and the unusual engagements utilizing both helicopters and horse cavalry in the vicinity of the Gerögera Mountains. The Emergency climaxed with the amphibious and airborne assault on the island of Moynrout on May 3rd, 1976, liberating the federal capital and resulting in the end of the Laberenzites as a coherent force with the suicide of Ocatvya Laberenz. Before committing suicide by handgun, Laberenz wrote an extensive list of her co-conspirators, which was found in her jacket pocket, most of which were able to be verified, greatly expediting the process of bringing those responsible for the coup to justice. While minor incidents and fighting continued, by autumn of that year the Laberenzites had ceased to exist as a movement and the National Radical League had dissolved.

The Emergency resulted in yet another massive transformation in Wazhenaby society. It cemented the necessity of anti-authoritarian, anti-racist, and restorative measures throughout Wazhenaby institutions, culminating in the Decolonization Acts of 1977, presided over by Chancellor Nauċau Holwerda, which radically reformed the way land use and confederation were implemented in the country over the next several years, with massive swaths of land being repatriated to regional stewardship committees, usufructuary becoming the default form of land ownership, and all of the country's commonwealths becoming legally independent sovereign entities. The concepts of militant democracy, permanent agitiation, and ethnic autonomy became enshrined in Wazhenaby politics.

Following the Emergency and scrubbing of Laberenzite elements from the military and intelligence community, an intense rivalry developed between the two apparatuses as their new leadership endeavored to win back the trust of the people and government. While the military was a typically well-trained and equipped volunteer force that frequently cooperated with the militaries of North Ottonia and Zacapican, the intelligence community often enjoyed greater publicity and public praise for its high-profile support of guerrilla forces and humanitarian work abroad. This rivalry sometimes led to breakdowns of communication and cooperation between the military and intelligence agencies which hindered their effectiveness, which would become highly problematic by the 1990s with the beginning of the Second Osawanon War.

The Second Osawanon War between Wazheganon and Moxaney began on August 24th, 1993. The instigating incident is unknown, but is generally believed to have been the escalation of a cross-border skirmish a few days prior. Such skirmishes had been fairly routine since the First Osawanon War seventy years prior, usually involving fistfights or inaccurate warning shots at border crossings or between passing patrols, and it is uknown what may have caused one to escalate into active combat. Moxaney, which had long planned for such an escalation and invasion, rapidly mobilized its forces, with materiel and intelligence aid from Gristol-Serkonos; meanwhile, the military-intelligence rivalry in Wazheganon resulted in the military being largely unaware that a mobilization was taking place, and being caught unaware on the evening of August 24th. Wazhenaby forces were unable to scramble their mostly superior air assets before Moxi air assault and airborne troops had mostly bypassed their entrenched positions, ruined several airfields, and taken several strategic logistical points, causing defenses at the front to quickly crumble from lack of supplies or air cover. By the time a large response force arrived in Bewenak from the north, Wazhenaby forces were on the back foot, and, despite several promising counter-offenses, Wazheganon was forced to concede the territory on November 9th, 1997. The entire commonwealth of Bewenak was annexed in Moxaney, representing a loss of nearly 25% of Wazheganon's total territory. The war unofficially continued for several years after the signing of the treaty, as local militias made use of abandoned Wazhenaby equipment and Wazhenaby volunteers repeatedly crossed the border with new equipment and supplies. By the mid-2000s, the conflict had dropped in intensity, with most resistance carried out by clandestine guerrilla groups, and the conflict continues to this day. The Second Osawanon War represented the effective end of the Osawanon Community as a functional international organization, although Wazheganon and Moxaney both retain full membership.

Following the war, Wazheganon began a serious audit of its military and intelligence leadership in an attempt to prevent such an institutional failure from repeating, and began seeking much closer military-diplomatic ties with other Leftist countries. In particular, Icniuhyotl Expeditionary Base was opened in 2003 near Wesdawytl, Oscandowa, in the vicinity of Muwïn Naval Base, establishing a permanent Zacapine military presence in Wazheganon and the northern Salacian Ocean. Wazheganon pursued defensive arrangements with Belisarian socialists countries such as North Ottonia, Ostrozava, and Scipia's Talahara, and became more open to cooperation with Jhengtsang and Elatia. This eventually led to Wazheganon's role as a founding member of the Kiso Pact in 2019. In March 2021, Wazheganon engaged in minor naval and air skirmishes with Gristol-Serkonos over the crash of the experimental X-704 aircraft in Wazhenaby territory. In June 2021, the Federal Armed Forces deployed to Enyama in support of the Democratic Coalition in the Enyaman Civil War, simultaneously announcing the right of the Wazhenaby navy to inspect and turn away ships entering Winivere Bay, triggering international outcry.