Native Imaguan people

The reason given is:

Last edit by: Luziyca (talk · contrib) · Last edited on Sun, 15 Dec 2024 07:00:08 +0000

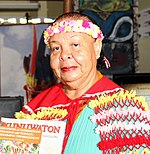

A gathering of native Imaguans, 2016 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 7,180 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| File:ImaguaFlag.png Imagua and the Assimas | 6,532 |

| 648 | |

| Languages | |

| Estmerish, Vespasian, Western Imaguan Creole, and Eastern Imaguan Creole, historically Imaguan | |

| Religion | |

| Sotirianism | |

Native Imaguans (Vespasian: Imaguani nativi, Western Imaguan Creole: Inhodi, Eastern Imaguan Creole: Nativ Imagwatsu or Nativ Imagwawi), or Mutu (Imaguan: Mutu) are the indigenous people of Imagua and the Assimas, inhabiting the archipelago for several centuries before the arrival of Euclean explorers and settlers.

Native Imaguans are a subgroup of the broader native Arucians, who are part of the even broader Asterian indigenous peoples.

Etymology

The name Native Imaguans derives from the fact that native Imaguans are indigenous to the archipelago that would come to form Imagua and the Assimas. Other terms, such as Inhodi in Western Imaguan Creole (from Geatish infödda), or Imaguani nativi are translations of the term into their native languages. These terms are still widely used in Imagua, and is seen as acceptable.

The other commonly used term, Mutu, derives from the Imaguan language word for people, and since the 1990s has been gaining in popularity, as many native Imaguans view the term "native Imaguan" as being derogatory, due to its historic associations with colonial rule.

History

Pre-contact

It is believed by archaeologists and historians that native Imaguans came from the Kajapas region in what is now present-day Vilcasuamanas, with the ancestors of the native Imaguans arriving on present-day Imagua and the Assimas in the 700s CE, displacing the Nati people who inhabited the archipelago for centuries.

For the centuries preceding contact with the Eucleans, native Imaguans had extensive trade relations with their neighbours, with potatoes being the predominant crop, with potatoes and other crops from the islands often traded for precious metals like gold, which they fashioned into jewelry.

According to the earliest explorers, the natives were divided into village-based societies, with each chief only ruling over an individual village. One explorer, (TBD), explicitly compared the village-based societies of the native Imaguans with the Bahian village system used by certain Bahian societies at that time.

Early colonization

With the discovery of Imagua and the Assimas by Caldish explorers in the 1490s, native Imaguans made first contact with non-Asterians for the first time. According to Caldish explorer (TBD), who was the first person to land in present-day Cuanstad:

"...when we set foot on dry land, we were greeted with curiosity by the native inhabitants of the land. After exchanging some gifts with one another, it seemed like a friendly relationship was being developed, with the natives willing to take care of us."

While relations between Eucleans and the native Imaguans started out well, especially in the first part of the sixteenth century, after the islands were taken from Caldia by Geatland in 1562, relations between the natives and Eucleans deteriorated, especially as the Gats would begin to enslave native Imaguans. This would result in the reduction of the population of the native Imaguan population on the islands from around 25,000 in 1450, to between 2,000 and 3,000 people by 1650, with most surviving native Imaguans residing in the interior of the island of Imagua, and virtually none left on the Assimas Islands.

Many of the surviving natives became hostile to Eucleans, especially as a result of the enslavement of many native Imaguans.

Euclean rule

After Estmere seized the island of Imagua from Geatland in 1658, pressures on the native Imaguans eased, especially as Estmere imported slaves from trade posts in present-day Rwizikuru, leading to the establishment of the current Bahio-Imaguan population on the islands.

By this point, virtually all of the native Imaguans resided along the northeastern slopes of Mount Apita in present-day Saint Fiacre's County and Saint Isidore's County. Thus, in 1662, Governor (TBD) ordered that "all remaining free natives be moved towards a section of land in northern Saint Fiacre's and eastern Saint Isidore's" in order for them to "preserve their traditions and culture," while banning Euclean settlers from owning land in that reserve, and prohibited Eucleans from attempting to enslave them.

The Topuland Territory (Imaguan: Ubou dübü) was therefore set aside to be the home of the native Imaguans, and by 1667, a report said that "search parties have found no evidence of free natives who are inhabiting the area outside of the Topuland region," suggesting that all free natives had been moved to the Topuland Territory.

In the Topuland Territory, a chief (Imaguan: ábuti) was appointed by the colonial governor from among the native Imaguan population, while checkpoints were established to prohibit natives from exiting the territory, while Eucleans were only allowed to travel through the territory with an armed escort, and were prohibited from settling the territory, or otherwise "disturbing their native culture."

Over the next century, enslaved natives were assimilated into the Bahio-Imaguan community, while those in the Topuland Territory were able to better preserve their culture. However, traditional religions faded out, as Gospelite, and later, Catholic missionaries spread to the Topuland Territory with the permission of the governor and the chief. During Gaullican rule of Imagua... (TBC)

After the reconquest of Imagua from Gaullica by Estmere in 1771, and the subsequent abolition of slavery, the freed native slaves were sent to the Topuland Territory. Thus, it was decided to do a census of the "natives" living in Topuland. They found that there were 8,596 natives residing there, of which only 2,579, or around 30%, were "free natives," and the majority of the population, or 6,017 people, were former slaves.

With the influx of former slaves into Topuland, who were extensively influenced by the cultures of both their Euclean slavemasters and the Bahian slaves, tensions mounted between the two communities, as many native Imaguans feared that the "black Imaguans" would destroy their culture and prohibit them from living their traditional lifestyles.

This came to a head in 1783 when after the death of Chief Jehannin, the Estmerish authorities appointed Osmund Freeman, a freed native slave as chief. This appointment was seen as an insult to many native Imaguans, as Osmund Freeman "had more in common with the black inhabitants than with the natives."

This caused many prominent "free natives" to elect Darila as chief. However, Darila's election was rejected by the Estmerish authorities, who recognised Osmund Freeman as the legitimate chief of the Topuland Territory, which led to a rebellion led by Darila to force Estmere to recognize him as chief over Osmund Freeman.

However, the rebellion was not successful, as Darila's forces were all but destroyed at the Battle of Gurasu, due to superior numbers of Estmerish troops and colonial militias. Darila was forced to surrender, and he was executed. However, as a compromise, the Estmerish authorities agreed to permit "the freed native slaves" to live outside of the territory, so long as they "follow civilised customs." This allowed most of the former slaves to leave the Topuland Territory, which helped reduce tensions between the two groups.

Assimilation

In the nineteenth century, native Imaguan autonomy began to be eroded when in 1811, after the death of chief Osmund Freeman, the Estmerish government chose to appoint both a chief, Gurasu Brown, and a superintendent (Imaguan: ligeleina), Noble Thurman, with the superintendent's role to "civilise the natives" and to "prepare them for life in civilised society."

The appointment of a superintendent in addition to the chief weakened the role of the chief, as many of the superintendent's duties overlapped with those of the chief. While Brown attempted to defend his administrative responsibilities, Thurman argued that "natives lack the capacity to properly govern themselves," and thus needed a "civilised man" to govern the reserve.

Thus, over the next few decades, the powers of the chief diminished to purely a cultural role, while the superintendent's position grew, until by 1851, the superintendent received the prerogatives to "appoint chiefs."

In 1864, superintendent James McMillan issued a policy requiring that all "native children be educated in Euclean culture and Euclean customs, so that they may be able to function in a Euclean society." To this end, a school was established in Bellmare specifically "for the education of native children." When the chief criticised the distance of the school from the Topuland Territory, McMillan said that the distance was critical to ensure that "they be integrated into the mainstream society."

As well, under James McMillian's tenure as superintendent for the Topuland Territory, he urged that a census be done on the natives, and to only count those "whose fathers are natives," in order to ensure that "no man may fraudulently claim that they are native." The suggestion of a census under those lines were criticised by many natives, but the colonial government supported it, and approved a native census to be taken under McMillian's lines.

Thus, the 1871 census revealed there were only 2,521 natives on the island, of which 2,344 lived in the Topuland Territory. With the figure in hand, McMillian argued that "alienated sections of the Territory ought to be opened up for development by civilised men," especially those deemed "fertile lands." The following year, the governor instituted the Land Alienation Ordinance, which empowered the colonial authorities to take "alienated lands" away from the Topuland Territory, and to sell them to Imaguans. This ordinance was used to seize the lands of what is now Thorebourne Naval Base from the natives.

When the Colony of Imagua was granted limited self-government by the Estmerish in 1892, native Imaguans did not have a say in government, as they were deemed "not ready" for the responsibilities of citizenship. However, as the assimilationist policies took hold, the Topuland Territory was granted a territorial council (Imaguan: damuriguaü) in 1904, comprising of three elected officials, and six officials appointed by the superintendent.

However, real power still lay within the hands of the superintendent, although as the natives were "trusted" with more and more powers, the superintendent's powers were reduced, while the number of elected representatives grew: by 1948, the last superintendent, Gilbert Charrier said that "the natives in the territory have developed to such a point that there is no longer any need for any special rights or privileges," and argued that the continued existence of the Topuland Territory was "inherently discriminatory."

Thus, in 1949, the Native Integration Act passed both chambers of Parliament, and was signed into law by President Walter Redmond Keswick, which transformed the Topuland Territory into the village of Topuland, granted all native Imaguans citizenship, and "terminated" all special rights and arrangements, with immediate effect. As well, all property in Topuland was to no longer be owned communally, but instead to be owned by "residents residing on the former territory," in a "fair and proportionate" way.

While many native Imaguans were relieved that they were finally receiving citizenship, most were upset to hear of the termination of the special rights and arrangements, as they feared that they would lose their culture to the dominant culture of the islands.

Thus, the final chief, Malcolm Shelvey criticised the act, as he believed that the act was an "underhanded way to further assimilate and destroy our native culture," and criticised the fact that the communal lands were now being divided up between residents, as Shelvey said that this would only "serve to weaken our community for the benefit of colonial elites."

Nonetheless, the government pushed ahead with those plans, and later that year, Shelvey became Mayor of the village of Topuland. By 1951, there were 2,507 people registered as "Native," of which 1,681 lived in Topuland, and the remainder lived outside of it, mostly in Nua Taois.

Urbanisation

During the 1950s and 1960s, more and more natives left Topuland, primarily to Nua Taois and Cuanstad as they sought greater opportunities outside Topuland. In the cities, many natives found themselves in an unfamiliar environment, with one native writing in 1953 that Nua Taois was "accelerating the loss of our culture, because in Nua Taois, we realise just how few of us there are left on our native land."

Relations between natives and other ethnic groups, like the Bahio-Imaguans and Eucleo-Imaguans were at best, "ambivalent," as their small population made them a "mere curiosity" in the Imaguan nation. However, many natives continued to face discrimination, especially in Nua Taois and in rural areas in northern Imagua, with natives often ending up in "dead-end" positions.

In the 1961 census, there were 3,105 natives, of which only 1,022 lived in Topuland, 854 lived in Nua Taois, and 811 living in Cuanstad, with the remainder living elsewhere in the country, including one person in San Pietro.

During the 1960s, as more natives left for the cities, tensions began rising, as many Bahio-Imaguans and Eucleo-Imaguans viewed the growing native population as "increasing crime rates" in Imagua. In 1966, of the 1,014 prisoners on the island, 391 were Native Imaguan, or around 38.6% of the prisoner population, despite only making up 0.25% of the national population.

As well, with the death of Malcolm Shelvey in 1967, he was succeeded by Harvey O'Concannon, who would be an activist. Under O'Concannon's tenure as Mayor of Topuland, he advocated for increased native rights, as he argued that the policies of the government, regardless of political affiliation, were "harming the culture of Native Imaguans," and urged the government to "recognise that we are the original inhabitants of the land." While in 1969, Prime Minister Eric Fleming did recognise the natives being the "original inhabitants of these islands," he was hesitant to allow them to file land claims, as he feared that it would undermine Imagua's social order, and would harm his popularity among the general Imaguan population.

By 1971, the native population rose to 4,122 people, or 0.33% of the national population. Native Imaguans were concentrated in Nua Taois, with 2,154 living there, in Cuanstad, with 1,011 in Cuanstad, and only 769 living in Topuland.

During the 1970s, the first native association was established in Nua Taois, the Native Imaguan Association, to advocate for greater indigenous rights in Imagua, as well as restitution for "nearly five centuries of colonial oppression." While crime rates decreased, tensions between the native Imaguans and non-natives remained, especially in Nua Taois.

By 1981, the native population rose to 4,957 people, or 0.41% of the national population, with only 613 people living in Topuland. During the 1980s, awareness of native rights increased, with Edmondo Privitera giving an apology in 1989 to the native Imaguan population for "the abuses committed by Imagua and her colonizers" in the nearly five hundred years of "Euclean domination of the Asterias." An agreement was signed in 1990 which allowed the Imaguan language to be used for government services within Topuland, as well as gave the municipality some more powers.

Contemporary era

In the 1991 census, the population of Native Imaguans rose to 5,415 people, or around 0.44% of the national population. Only 602 lived in Topuland, with 2,347 living in Nua Taois, 1,479 living in Cuanstad, and the remainder scattered across Imagua.

The 1990s saw increasing awareness of indigenous issues: following the death of Mayor and de-facto chief Harvey O'Concannon in 1993, he was succeeded by Meredith Spencer, the first female to ever be elected mayor of Topuland, and the first chief of the Native Imaguan people to be a woman since colonisation.

Under Meredith Spencer, the Native Imaguan Association continued advocating for restitution, filing a lawsuit against the Imaguan government in 1996 to request one billion shillings (3,365,690,695ſ44 as of 2019, or €58,819,027.70) as restitution for the damage caused by colonialism. The lawsuit was rejected by the Supreme Court in 1999, which ruled that as "all of the abuses alleged by the plaintiffs occurred prior to Imagua's independence in 1948," the matter was ultra vires.

In 2001, the population rose to 5,838 people, comprising around 0.46% of the national population. By that point, only 503 people lived in Topuland, with most people living in either Nua Taois, or Cuanstad.

During the 2000s, indigenous issues were largely ignored by the governing Sotirian Labour Party, although the Citizenship Act of 2005 officially recognized the citizenship of Native Imaguans. Despite this situation, the Native Imaguan Association continued to exert influence over Imaguan society, with the Native Imaguan Association continuing their advocacy for indigenous issues. In 2004, the former boarding school in Bellmare was turned into a museum to the history of indigenous peoples in Imagua, and in 2007, Topuland expanded for the first time, when the government of Saint Isidore's transferred "abandoned farms" previously part of Topuland back to Topuland.

By 2011, the indigenous population on Imagua and the Assimas rose to 6,532 people, or around 0.5% of the national population, with 3,266 living in Cuanstad, 2,177 in Nua Taois, 366 in Topuland, and the remainder scattered across the country.

During the 2010s, under the premiership of Edmondo Privitera and Douglas Egnell, addressing indigenous issues became a priority of the government, albeit a small priority, with the government giving the Native Imaguan Association five billion shillings in reparations in 2015, and establishing a Ministry of Indigenous Affairs in 2016, with the first elected indigenous MP, Helen Ilumani appointed to that role. Despite this increased focus, indigenous issues are generally seen as "low priority" by most of the political establishment. However, the native Imaguan language was declared extinct in 2019, when 107-year old Judith Brown died in Nua Taois, meaning all surviving speakers are second-language speakers.

Culture

Arts

Prior to colonisation, Native Imaguans were renowned for their jewellery and their music, as well as basket-weaving. To this day, many native Imaguans are still known for their jewellery and basket-weaving, with prominent basket-weavers being Godfrey Awanda and Hiluma Foster. As well, native Imaguan music has played an influential role in shaping the music scene of Imagua and the Assimas, with the most prominent native singer of recent times being Uran O'Phelan, whose career spanned from 1974 until his death in 1993.

However, since colonisation, native Imaguans have been influenced by Euclean traditions, with painting becoming widespread. Prominent native painters include Barry O'Davoren, Jim Blake, and Bob Nerney.

Cuisine

While since colonisation, native Imaguan cuisine has played a negligible role in shaping the cuisine of Imagua and the Assimas, native Imaguan cuisine is still widely consumed by native Imaguans, with a popular staple food among natives being ereba, which is often eaten with fish as a side. Other dishes consumed by native Imaguans include potatoes, sweet potatoes, and hutias.

Demographics

As of the 2011 census, there were 6,532 native Imaguans residing in Imagua and the Assimas, which is defined as being a "child of a native father." The city with the highest number of natives is Cuanstad, with 3,266 people identifying as Native Imaguan, but the municipality with the highest percentage of natives, and with a population of over 1,000 people, is Nua Taois, with 2,177 people, or 2.3% of the population identifying as Native Imaguan. However, the municipality with the highest total percentage is Topuland, where out of the 460 inhabitants, 79.6%, or 366 people, are native Imaguan.

If one includes maternal links, it is believed that around 20%-40% of the population of Imagua, or between 261,301 and 522,602 people have a native Imaguan ancestor, with the ratio largely split evenly between the Eucleo-Imaguans and Bahio-Imaguans.

Religion

Historically, native Imaguans followed religions not unlike those found in the rest of the Arucian Sea, with a belief in polytheism. However, with the colonisation of Imagua and the Assimas by Euclean powers, Sotirianity was introduced to the islands.

Today, 98% of the native Imaguan population, or 6,401 people are Sotirian. The largest sects of Sotirianity practiced by the native Imaguans are Gospelite, with 4,673 people, or 71.5% of the native population believing in it, followed by the Solarian Catholicism, with 897 people, or around 13.8% of the population practicing it. Other sects of Sotirianity make up the rest of the Sotirian population.

Of the remaining two percent of the native population, or 131 people, most of them practice traditional religions, although some practice other religions, predominantly Irfan.

Despite this, most native Imaguans still practice ancestor worship.