Lhedwinic Council

| Constitution of the Glanish Commonwealth | |

|---|---|

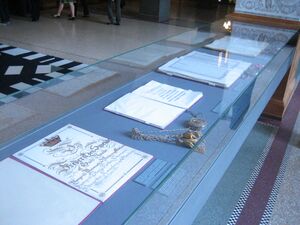

A photograph of the Constitution in its display case. | |

| Created | 21 February 1900 |

| Ratified | 5 March 1900 |

| Location | Presidential Library, Vænholm |

| Author(s) | Sebastian Thuesen, Otto Knudsen, Ivar Lange |

| Signatories | Alex Åberg (first President of Glanodel) |

| Purpose | Formation of the Commonwealth and Supreme Law of Glanodel |

The Constitution of the Glanish Commonwealth (Glanish: Grundlov), sometimes referred to as the Second Glanish Constitution, is the supreme law of Glanodel. It is the second and current constitution of Glanodel and establishes the Commonwealth as a federal republic composed of 13 cantons (federated state. Following the end of the Great War in 1899, a Constitutional Conference was held among the leaders of the Glanish Resistance Movement, which had served as the nation's de facto provisional government. Drafting of the document began on 1 February 1900 and after seven revisions, the final draft was ratified on 5 March 1900.

The document is composed of a preamble, which establishes the reasons for founding the Commonwealth and priorities of the new government, its six original articles. Its first three articles entrench the doctrine of separation of powers, dividing the federal government into three branches (legislative, executive, and judicial). Article Four, often referred to as the Bill of Rights, defines Glanish citizenship and federally protected individual and popular rights, and establishes the federal institution of popular referenda. Articles Five and Six entrench concepts of federalism, describing the rights and responsibilities of cantonal governments and of the cantons in relationship to the federal government.

Since the Constitution came into force in 1900, it has been amended three times to meet the changing needs of the country. The First Amendment establishes a broad basis for the nation's publicly-funded pensions, universal health care system, and public and private education systems, and the funding mechanisms for each. The Second Amendment further defines the right to protest and the rights of organized labor. The Third Amendment expands the federal government's authority to regulate commercial activity within the nation. Amendments to the Constitution or changes to federal laws that have no foundation in the constitution but will remain in force for more than one year must be approved by the majority of both the people and the cantons, a double majority.

History and context

Main article: History of Glanodel

Preamble

The Preamble is the introductory statement to the Constitution of the Commonwealth and serves to state the purposes and intentions behind the ratification of the Constitution. Since the Constitution's ratification in March of 1900, the Preamble has been cited in numerous court cases involing constitutionality to provide context regarding the document's original intent. Most political scholars have come to view the first sentence of the Preamble as one of the most defining and indicative of the true purpose behind the Commonwealth's founding.

"When a people find themselves freed of the chains of foreign oppressors, a reflection of past mistakes committed by those people and by those entrusted to protect and serve them becomes necessary, and an endeavor to avoid the repeating of those mistakes, imperative."

Articles

Article I: Legislative Branch

Article One establishes the federal legislative branch of the Commonwealth, the Landsmeet (Glanish: Landsmót), its two chambers, and the positions of the Chancellor of the Upper House and Speaker of the Lower House.

Section One grants the Landsmeet sole, federal legislative power. Section Two establishes the powers of the Landsmeet such as the authority to tax, borrow, pay the nation's debt, raise and maintain a standing army and navy, and create programs, agencies, or organizations to provide for the general welfare of the population.

Section Three describes the upper house, the Højerhuset (Glanish: Højerhuset i Landsmót), defines its exclusive powers (such as approval of Supreme Court justices), and establishes the role of the Chancellor of the Upper House. Section Four describes the lower house, the Underhuset (Glanish: Underhuset i Landsmót), defines its exclusive powers (such as impeachment of federal executive officers), and establishes the role of the Speaker of the Lower House.

Section Five defines those who are eligible to serve as a member of the federal legislature within both houses. It describes the election procedures for both houses and defines the nation's party-list proportional representation election system. It also defines how long and how many times a representative can serve, and how they can be removed from office, as well as the procedures in the event of resignations or deaths while in office.

Section Six defines the process of congressional oversight.

Article II: Executive Branch

Article Two establishes the executive branch of the federal government, its purpose and powers, its exclusive authority (actions which can be taken without the authority of the Landsmeet), as well as the Office of the President, their cabinet, and the President's authority in foreign affairs.

Section One establishes the President of the Commonwealth as the "head of state and government" and the nation's highest ranking public official. It also tasks the President with "leading the executive branch of government in the execution of the nation's federal laws, as well as other duty tasked to the President by the lagislature".

Section Two defines the presidential election process and the necessary qualifications for holding the office, as well as the length of presidential terms and their term limits. It also defines impeachment procedures and restates that the power to impeach a seating president is vested in the Lower House.

Section Three describes the President's authority and role as the nation's commander-in-chief. It also grants the President the authority to make a retaliatory declaration of war ("to declare war in retaliation for an act of war against the Commonwealth").

Section Four describes the President's Cabinet as "those to whom the President may delegate temporary authority to enforce federal law." It also defines the process for appointing Members of the Cabinet and officially defines their position and duties as "serving at the pleasure of the President".

Section Five establishes the procedures for removing other federal officers.

Article III: Judicial Branch

Article Three describes the nation's court system (the judicial branch) and establishes the nation's Supreme Court. It defines court cases which should be brought before the Supreme Court, as well as lower federal courts. It establishes the qualifications for serving as a Supreme Court justice and the appointment and approval process. It also grants the legislature the authority to create lower courts while granting jurisdictional authority over all lower courts to the national Supreme Court. Article Three also protects the right to a trial by jury, the right to due process, and the writ of habeas corpus. It also defines the crime of treason.

Article IV: Citizenship and Fundamental Rights

Article Four is the longest Article of the federal Constitution and both defines Glanish citizenship (as well as other forms of residency) and contains the nation's bill of rights.

Sections One through Eight provide: a definition of Glanish citizenship; a list of rights granted to citizens, but not guaranteed to non-citizen residents (such as voting in federal elections), a definition of Glanish permanent residents, asylum seekers or refugees, and temporary residents; a definition of illegal immigration; and a list of conditions and justifications for the revocation of citizenship.

Sections Nine through Twenty-One refer to the concept of "human dignity" and while intentionally vague so as to enable a broad interpretation of the term, they do specifically prohibit certain actions by the state or public, and protect certain individual and group rights, such as the prohibition of arbitrary treatment and torture, right to privacy and life, equality before the law, and the the prohibition of public discrimination (the scope of which has been broadened several times). They also define and prohibit cruel and unusual punishment and illegal search and seizures.

Sections Twenty-Two, Twenty-Three, and Twenty-Four guarantee certain group rights, or the rights of organizations, such as political parties, trade unions, and private enterprises.

Sections Twenty-Five through -Nine specifically address voting rights, such as guaranteeing the right to referenda. Sections Thirty through Forty address individual liberties and are intentionally vague so as to allow broadened protections for individual rights. These Sections have come to support a wide variety of personal liberties most notably freedom of assembly, association, speech, the press (and media), and religion, as well as the freedom of domicile and protections against extradition without consent. Section Forty-One establishes a mandate for providing public, primary education.

Sections Forty-Two through -Nine protect the economic freedoms of citizens and residence within Glanodel, such as the right to property, free choice of profession, and the right to engage in private enterprise. It also guarantees the right to unionize, strike, and protest.

Section Fifty describes the nation's conscription policy, as well as the right of conscientious objection.

Article V and VI: Federalism and the Cantons

Articles Five and Six describe the cantonal governments, their authority within the federal framework of the government, and their relationship to the federal government, and their relationship to foreign entities.

Article Five, Sections One and Two define the rights of cantonal governments to ratify constitutions lesser than the federal constitution. Article Five, Sections Three through Five grant the authority to form both cantonal and lesser governments, while mandating democratic elections. Article Five, Section Six further defines the role of cantons in the election of representatives to the Upper House of the Landsmeet.

Article Six, Sections One through Four delegate matters of civil and criminal law enforcement, education, public construction, energy production, and transportation to the authority of the cantons. Article Six, Sections Five and Six prohibit the cantonal governments from forming trade-, immigration-, legal/criminal-, or military-related agreements with foreign powers.

Article Six, Section Seven addresses cantonal authority to tax and borrow. It also addresses specific conditions in which the federal government is required to provide aid to cantons in the event of financial crisis or disaster.

Amendments

The First Amendment (1933), intended to expand upon the government's responsibility to provide for the general welfare of the people states in the Preamble, established the nation's publicly-funded pensions and its funding mechanism payroll taxes.

The Second Amendment (1936), commonly referred to as the Worker's Rights Bill, provides increased broader protections for the right to protest and provides increased legal protections for trade unions.

The Third Amendment (1939) expanded the mandate that governments provide public education to include public universities and colleges, a funding mechanism and terms for subsidizing educational programs, and addressed the terms for public funding and regulation of private education.

The Fourth Amendment (1940) established the nation's current system of universal health care. It also established its funding mechanism and the requirements of the federal government to subsidize cantonal health-care spending. Finally, it also delegated the responsibility for administering health care programs to the cantonal governments, which has since become the canton's primary area of responsibility.

The Fifth Amendment (1942), commonly referred to as the Anti-Trusts Bill, expands the federal government's authority to regulate commercial activity within the nation. Most notably, it gave the federal government the right to impose new economic regulations, expand its authority over monetary policy, impose industry, product quality, and safety standards, prohibit certain industries "so long as the prohibition of such industries does not infringe upon the rights expressed in Article Four". Finally, it also enabled the government to legally break up trusts, or "business or industry practices which infringe upon the effectiveness of competition within Glanish markets."

Judicial review

The way in which the Constitution is applied in areas of civil or criminal law, political processes, or government authority, depends upon and is ultimately shaped by how the courts of Glanodel interpret the document.

Referred to as judicial review, this practice is considered a hallmark of Glanish law and grants courts the authority to examine legislation and government activity and decide their constitutionality, and to strike them down if found unconstitutional. Judicial review includes the power of a court to explain the meaning of the Constitution as it applies to particular cases. Over the years, court decisions on issues ranging from federal and cantonal regulations to the rights of the accused in criminals have changed the way many constitutional clauses are interpreted, without amendments to the actual text of the Constitution.

Legal professionals in Glanodel generally take one of four approaches when interpreting the Constitution and discerning its meaning with regards to modern legal questions. The first, and most prevalent, is the living constitution interpretation which asserts that "the founders intentionally wrote the Constitution is broad and flexible terms so as to provide the nation with a dynamic, 'living' framework for the operation of the country in a dynamic and ever changing world." The second most prevalent is the original meaning interpretation which asserts that the "founders intended the Constitution of the Commonwealth to be understood in a hundred years, the same as it was understood the day it was ratified."

Church and State

The Glanish Supreme Court has upheld a long standing statute that the Constitution implies a strict separation of church and state, although the document never explicitly mentions this phrase nor expressly forbids church involvement in state affairs. Section Five of Article One, Section Two of Article Two, and the Qualifications Clause of Article Three, as well as Sections One through Eight, Twelve, Fifteen, Nineteen, Twenty-Two, Twenty-Five through -Nine, Thirty-Four and Fifty of Article Four are the primary citations used in court cases challenging church and state entanglement.

Section Five of Article One, Section Two of Article Two, and the Qualifications Clause of Article Three all refer specifically to the prohibition of religion as any prerequisite of eligibility for holding public office. Sections One through Eight of Article Four specifically prohibit the use of "religious tests" when considering a person for admittance into the Commonwealth and prohibit depriving a person of citizenship or residency "on the basis of religion.". Section Thirty-Four of Article Four, which specifically addresses the freedom of religion, states, "As religion is a matter which lies exclusively between a man and his God, the state has no place in the affairs of religion nor any authority to restrict the free exercise thereof."

State transparency and freedom of information

While it is not explicitly addressed in the Constitution, numerous sections and clauses of the Constitution have been used throughout the nation's history in order to create an implied policy of freedom of information and government transparency.

The first court case related to this issue was in May of 1923 and was filed against the cantonal government of Siwald for its attempts to restrict the distribution of a conservative newspaper. When justices were presented with the newspaper's accurate coverage of a conspiracy between the government and local businesses who wanted exclusive rights to energy production in select, advantageous areas of the canton, the Supreme Court of Siwald ruled in favor of the plaintiff. While this court decision primarily focused on ensuring freedom of the press, a second lawsuit was filed in July of 1923 by a plaintiff demanding that the government be obligated to provide any and all documentation of state-related activity upon request. The Court stated that, "As all governments should be founded for the purposes of promoting the welfare of the people within its area of responsibility, a government's actions must be available to all those people."

Two years later, because of the implications of this ruling, another lawsuit was filed in 1925 with the Supreme Court of Glanodel to challenge the lower court's ruling. In the end, the federal court decided that, "It is paramount that a clear and consistent transparency be upheld by the state in the interest of its people, when such transparency is, or is no longer a danger to their safety. For how can a government be held accountable for its actions, if all its actions can be kept secret?"

In 1984, a lawsuit was filed by a plaintiff in Ileinskali against a local news station for, in the plaintiff's words, "the company's blatant disregard for [a person's right to] privacy." In the end, the case was elevated to a federal court which decided in March of that year that, "While transparency and freedom of information guarantees the right of the press [and media] to release information it feels relevant to the citizenry, the invasion of the privacy of individuals who do not hold positions with a measurable level of authority, power, or influence over the nation or others is not protected under such freedoms." Views of the this decisions are still widely debated, with some citing it as an abridge to freedom of the press and others citing it as a reinforcement of the right to privacy.

In 2006, a lawsuit was filed by the telecommunications company Telekom which claimed that a regulation passed by the Landsmeet in that same year directly infringed upon the right to free enterprise defined in the Constitution. Telekom was joined by several smaller companies involved in telecommunications, as well. After a three month long trial, the decision of the Supreme Court was that "because the government reserves the right to regulate commerce when it is in the interest of the people's general welfare," the Fair Communications Act is constitutional. Furthermore, the court stated that, "all companies which hold considerable influence over the distribution of information, lines of communication, and thus the people's ability to exercise their freedom of expression and speech, the state is not only allowed, but obligated to step in when business practices infringe upon individual liberties."

Political campaign finance

In 1962, a lawsuit was filed by the Bisgaard Foundation to challenge a law passed by the Villradäl cantonal government which restricted the amount of total political campaign contributions a single candidate running for a local office could receive in a given election cycle, as well as placing heavy restrictions on contributions received from private organizations.

After lesser courts and the Supreme Court of Villradäl ruled in favor of the cantonal government, followed by similar rulings from two federal courts, the case was escalated to the Supreme Court of Glanodel who, in November of 1964, also ruled in favor of the Villradäl government. In their decision they cited Sections Two, Three, Twenty-Two, Twenty-Five through -Nine, Thirty-Five, Thirty-Seven, and Forty-Six of Article Four, all of which address to some extend the individual or group right to contribute to and campaign for a political candidate.

The Supreme Court stated,

"A person is irrefutably entitled to donate their time and money in support of, or against, a candidate they chose. However, political influence should be reliant solely upon the status of a person's citizenship. Not a person's financial success, nor the virtues or status granted to them by birth should grant with that status any more or any less of a voice within our political process. Furthermore, the guaranteed right to contribute personal resources in favor of or against chosen candidates is a right reserved only by citizens and organizations founded by citizens for the express purpose of political action. A private enterprise is, by definition, not a single citizen, nor an organization founded for the purposes of political action. Thus, these entities do not reserve the right to donate in favor of, or against, a chosen candidate."

Since this ruling, the federal government of Glanodel, along with several cantonal governments, have passed laws which mandate strict accountability and reporting requirements for all private organizations involved in political action.