Pardarian Civil War

| Pardarian Civil War | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Zorasani Post-War Crisis | ||||||||

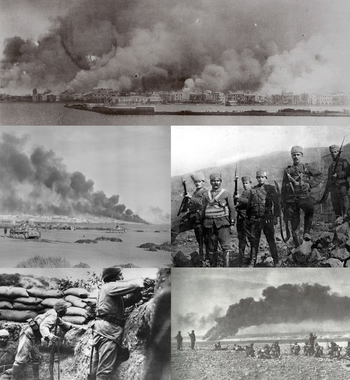

Clockwise from the top: Burning of Bandar-e Parvadeh, Soldiers of the Rasfanjani Clique at the Battle of Gamsar, Imperial troops at the Battle of Bandar-e Hassan, PRRC soldiers in 1948, PRRC tanks outside Chaboksar. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

Supported by |

Supported by Template:Country data Estmere |

Local walords and bandits | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | ||||||||

|

400 tanks 200 aircraft |

202 tanks 98 aircraft |

100 tanks 146 aircraft ~50,000-60,000 local militia under warlords | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

|

67,583 killed 118,300 injured 4,328 missing | 104,584 killed, injured or missing |

80,000-90,000 killed injured or missing 25,000-40,000 killed, injured or missing 75,000-100,000 killed injured or missing 21,508 killed injured or missing | ||||||

|

3.5 million displaced | ||||||||

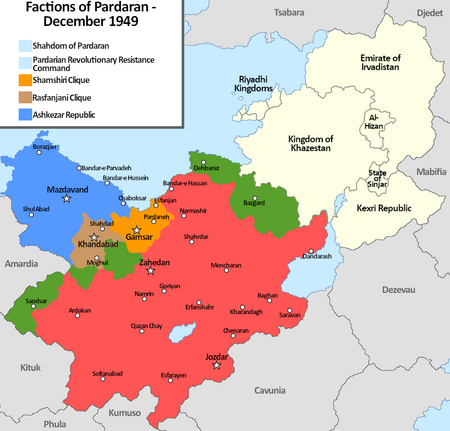

The Pardarian Civil War (Pardarian: جنك داخلی, Jangnegee-ye Pārdāri; Badawiyan: الحرب الأهلية السورية, al-Ḥarb al-ʾAhlīyah as-Fardarīyah) was a multifaceted civil war in Pardaran fought between the Imperial government of the Shahdom of Pardaran (SP), the Revolutionary Masses Party-led Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command (PRRC), the democratic Ashkezar Republic and numerous warlords lasting intermittently between 1948 and 1950. Though particular attention is paid to the period between 1948 and 1949, when the PRRC forces defeated the Shahdom of Pardaran, the war continued with the PRRC defeating opposing warlords and breakaway regions, culminating in the unification of Pardaran and the beginning of Zorasani unification, which would be completed in 1979 with the defeat of the People's Republic of Irvadistan and the establishment of the Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics.

The origins of the war lay with the failure of Ahmad Reza Shah to enforce his authority over all Pardaran following its independence from Etruria in 1946, following the Solarian War. The widespread opposition to his reign and his government's role as a former protectorate of Etruria resulted in the country fragmenting into various territories and polities. The largest rival to the Shahdom was the territory controlled by the Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command, an armed resistance against Etrurian rule that formed during the Great War following the Khordad Rebellion. The PRRC continued to resist against Etrurian during the Solarian War, securing itself a stronghold in southern Pardaran, with the backing and supply of neighboring Xiaodong. In the northwest, the multi-ethnic region of Ashkezar formed a democratic republic as a successor to the former Etrurian colonial region of Cyracana. Two charismtic figures, Hatami Ali Rasfanjani and Bavar Shamshiri Khan established strongholds of their own, each seeking to usurp the Shah. Between 1946 and 1948, all factions consolidated their territories and organised their forces, though to varying degrees of success. The same period saw sporadic and often costly clashes between the factions, while the PRRC utilised its ideology to destabilise the Shah's support base, while he also confronted political opposition.

The war began on April 10 1948, with the Imperial Government launching an offensive against the PRRC, in the aiming of securing territories lost in 1947. The offensive swiftly collapsed and a subsequent PRRC counterattack devastated the Imperial Pardarian Army. Carried by its own momentum, the PRRC offensive captured swathes of territory and encircled entire army formations, while the imperial and long-serving capital of Pardaran, Zahedan was encircled and besieged by December 1948. Zahedan fell to the PRRC in March 1949, while unable to recover effectively, the Imperial Army further suffered setbacks and losses in a renewed PRRC offensive in 1949, which led to the collapse of the Shahdom in October and the violent demise of the Imperial Family, including the Shah and Crown Prince. The same month the Shahdom official surrendered, this was followed by PRRC offensives against the Rasfanjani and Shamshiri cliques and imperial holdouts. The final PRRC offensives began in early 1950 and culminated in the final capture of all rival territories and the unification of Pardaran on 5 August 1950. Those associated with the losing factions who stayed were persecuted by the victorious Sattarists. With the establishment of a single-party state led by Mahrdad Ali Sattari in the aftermath of the war. From 1950 until 1952, Sattarist movements in neighboring Khazestan would agitate against the monarchy with Pardarian aid. This would lead to the Khazi Revolution and the unification of Khazestan and Pardaran in 1952.

The war became notable for the passion and political division it inspired and for the many atrocities that occurred, on both sides. Organised purges occurred in territory captured by the PRRC's forces so they could consolidate their future regime. Mass executions on a lesser scale also took place in areas controlled by the Imperials, with the participation of local authorities varying from location to location. The war also became the first major event of the Arduous Revolution, which would last another thirty-years.

Background

Etrurian colonialism

Prior to 1853, much of modern-day Zorasan had been ruled by the Gorsanid dynasty, a Pardaran based monarchy that up until the late 18th century had maintained Zorasan as a capable power. However, owing to entrenched traditionalist interests, repeated power struggles and unrest, the empire had steadily fallen behind its Euclean rivals. This backwardness was made apparent in the Sadavi War (1796-1798) against the First Etrurian Republic.

Following the Caltrini Restoration in 1810, the empire found itself facing renewed Etrurian aggression and the rising influence of other Euclean powers, specifically Estmere and Werania. This external pressure only deepened domestic woes, with numerous rebellions by disaffected nobles facing weak and ineffective Shahs. Over the next forty years, Zorasan would face numerous Etrurian incursions along the northern coast, with the First Etruro-Zorasani War (1832-1837) seeing the destruction of the Zorasani fleet and the ceding of virtually all Zorasani-Badawiya, alongside the port cities of Bandar Shahidi, Bandar Qassem and At-Turbah. The war further advertised the crippling weaknesses of the Zorasani state.

In 1848, Ali Ardashir became Shah and through a series of brutal purges and attacks secured unparalleled control over the imperial state. He began to seek out Euclean support in modernising Zorasan, often asking for advisers in exchange for economic concessions. In 1845, he signed the Treaty of Sabarvan with Werania, securing military advisers and weapons in exchange for access to Zorasan’s silver deposits in the south. Fearing a modernised Zorasan and oversized Weranian influence, Etruria launched the Second Etruro-Zorasani War (1846-1853).

The second war would devastate both Zorasan and Ali Ardashir personally. The Etrurians would rout his armies at every battle, inflicting heavy losses and demoralising his barely trained officers. The Etrurians continued to push toward the imperial capital at Razdavar, before ultimately besieging the city in 1852. Simultaneously, the Etrurians used money and promises of wealth to divide the Shah from his nobles, they secured a Badawiyan tribal revolt in 1849. In 1852, the Etrurians funded and supported a revolt by Qassem Shah in the north west. Both these events drew away valuable imperial forces, facing a besieged capital and a collapse in his armies morale, Shah Ali Ardashir surrendered on April 2 1853.

Partition and Etrurian rule

In wake of Zorasan’s collapse and surrender in 1853, Etruria sought to consolidate its control by partitioning the former empire. In June 1853, the defeated Shah signed the Treaty of Villa Barbarigo, formalising the Etrurian victory. Zorasani-Badawiya, alongside north-Western Zorasan were annexed directly and by 1860 had been reformed into Badawia Etruriana and Zorasan Etruriana respectively as colonial administrations. The Badawiyan tribal belt though within BE territory were granted significant levels of autonomy. Between both colonial territories, the Shahdom was continued through the newly established Shahdom of Pardaran, under Etrurian protection. The Gorsanid family were detained, with the House of Khorjandani put in power by Etruria. The Shahdom would have its foreign policy and defence managed by Etruria, with the colonial power further guaranteed exclusive economic access and large influence over its governance and administration.

To many historians, the origins of the PRRC’s victory and the ultimate success in Zorasani unification was the Etrurian policy of transferring colonial officers between its protectorates and colonial possessions. The Etrurians also promoted bi-lingualism among the educated colonial class to ease intra-colonial trade and business. As a result, a significant number of native Badawiyans and Pardarians spoke the respective other’s language. Historian Paolo Raffi noted, “through Etrurian colonialism, the entire Pan-Zorasani movement was born. Pardarian colonial officers would serve tours in neighboring Khazestan, Riyadha and vice versa, they would become fluent in Badawiyan, Pardarian and in some cases Kexri. This interaction bred a sense of solidarity and brotherhood under the Etrurian colonial boot.”

However, the most-stark consequence of the Etrurian partition of Pardaran was the widespread condemnation and resentment toward the puppet Shahs. Despite being the legal successor to the Gorsanid Empire, the Shahdom was seen as traitorous and self-interested. The Shahdom would never recovery from its signing of the Treaty of Poveglia, its support and legitimacy within its own territory was limited to the merchant and aristocratic classes.

In areas under direct Etrurian control, numerous draconian laws were introduced, limiting the space educated Pardarian nationalists could meet or organise. The Heydar Society, one of the first nationalist groups to form in 1899, was famously slaughtered during a group reading session by Etrurian colonial soldiers on May 5 1901. The Etrurian authorities also used asset seizures and confiscations to punish wealthy merchants if they were suspected of involvement with nationalist groups. This drove many movements underground, where secrecy above all else was the most valued trait in members. By 1910, there were over 50 Pardarian nationalist groups and movements operating across Etrurian colonial territories, as well as over 100 Badawiyan groups operating in Etrurian Bahia.

Khordad Rebellion

As the nationalist movement in Pardaran grew to include working class figures, it soon began infiltrate the Shahdom itself. In 1912, a group of officers in the Imperial Pardarian Army, met in a coffee house in Zahedan. There, they appointed Colonel Mahrdad Ali Sattari as their leader and the group began to arrange for mass mutiny and uprising against the Shah and the Etrurians.

The so-called Tabarzin (Battle Axe) group used their inherited wealth to smuggle rifles and supplies into Pardaran from other parts of the Etrurian empire and elsewhere, including Xiaodong. The Tabarzin then utilised trusted soldiers under their command to distribute weapons to civilians across the Shahdom. This would be continued for over six years, aided by the crippling corruption that was engulfing the Shahdom and Etruria’s colonial authorities.

In 1915, in wake of the Great Collapse, the Tabarzin stepped up their actions. Using bribes, they emptied entire arms depots of weapons, ammunition and explosives. They even began importing weapons by road from neighbouring states in broad daylight. By 1918, the Tabarzin had gained the loyalty of an estimated 25,000 imperial troops and had armed a further 30,000 civilians.

In the preceding three years, Etruria had begun to strip its possessions in Pardaran and Badawiya of industrial parts and financial assets to fund its recovery from the Great Collapse. This included a significant increase in mining activity, exploration for oil and gas and the confiscation of native property and wealth. Mass protests erupted across Pardaran and the wider Zorasani region, leading to the Tabarzin declaring a general uprising.

On May 18 1918, the Khordad Rebellion began with Tabarzin units capturing the holy cities of Namrin and Ardakan. Attempts at storming the Imperial Palace in Zahedan failed with heavy losses, this was followed by failures to capture Narmashir, Goriyan and Bazgard. The Tabarzin did see success in rural regions of southern Pardaran, before finally capturing Soltanabad, Jozdar and Esfarayen by August.

In response to the uprising, Etruria dispatched over 80,000 regulars from the mainland. Commanded by Leonardo Di Lauro, the Etrurian regulars alongside Etrurian colonial units rapidly beat the Tabarzin southward away from Zahedan. The Etrurians engaged in violent reprisals against native Pardarians, with over 18,000 killed by the end of 1918. Despite the losses, Ali Sattari ordered the Tabarzin in Etrurian-held territory to fight on regardless, sparking an insurgency on the Ardakan plains. In retaliation to guerrilla attacks, the Etrurians conducted numerous reprisals and also used chemical gas on the towns of Safarshahr and Ghazabad, killing an estimated 3,200 civilians. Throughout 1919 and 1920, the Etrurians slowly pushed the Tabarzin southward to the Xiaodongese border, while cracking down on rebels behind its lines.

At the turn of 1921, the Tabarzin was on the verge of collapse. Despite the support of Xiaodong, the Tabarzin had been evicted from Kumoso (which was part of the Shahdom at the time) and had lost Jozdar and Soltanabad. By the end of the year, the Tabarzin made their final stand at the Battle of Esfarayen against 50,000 Etrurian soldiers, backed by aircraft. The city would fall after three weeks of bitter fighting, forcing the Tabarzin leaders into exile in Xiaodong, who arrived in January 1922. The rebellion failed and left over 380,000 Pardarians dead, alongside 22,000 Etrurians. The Etrurians' failure to capture the Tabarzin leaders would prove crucial in the emergence of the Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command and later the civil war.

Great War

Between 1922 and 1928, the defeated Tabarzin leaders lived in exile in Xiaodong. There, they received strategic and tactical training from Xiaodongese military officers and monetary support from the government to maintain support and loyalty in Etrurian-held Pardaran. In 1924, the mark an evolution from its historic defeat, the Tabarzin became the Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command, operating under the ideology of Sattarism. The PRRC renewed its underground efforts to secure support across Pardaran, relying on the Shah’s perceived illegitimacy and his inaction as Etrurians killed thousands of civilians during the Khordad Rebellion.

The PRRC’s plan to return upon Etruria’s entry into any future global conflict was dealt a temporary blow after Etruria failed to enter the war alongside its allies in 1926. However, the Etrurian delay in entering the war until 1928, did grant the PRRC two further years to establish connections and insert political cadres.

When Etruria did finally enter the war in 1928, the PRRC, aided by Xiaodong, who fought on the opposing side to Etruria and its allies, invaded through the Kharkestar Corridor. Riding alongside a large Xiaodongese force, the PRRC re-entered Esfarayen on 22 June 1928. With Etruria forced to focus on its home fronts, its strength in Pardaran declined, enabling the PRRC to rapidly advance from Esfarayen. On August 5, the Etrurians dissolved the Shahdom and placed the imperial family under house-arrest, this enabled the PRRC to launch offensives into imperial territory and beyond.

The PRRC would reach the outskirts of Zahedan by February 1929, but was halted by determined Etrurian resistance, inflicting heavy losses on the PRRC and Xiaodongese. Utilising the Gadar River in the east, to hold off the triumphant Gaullicans and the “Invictus Line” in the south, the front in Pardaran stabilised by the Summer of 1929 and would remain static until early 1930.

In March 1930, the Gaullicans, PRRC and Xiaodongese launched coordinated offensives against Etrurian positions, breaking through and overrunning the Etrurian defenders. The PRRC entered Zahedan on 18 April, forcing the imperial family to flee with the Etrurians northward to Chaboksar. The Entente offensive stalled as it was held by the Honorius Line, travelling south-then-westward from Esfanjan to Moghul. During this time, the PRRC attempted to establish a functioning government over its territory. This period of control was in stark contrast to the civil war, as the PRRC avoided conducting mass executions or atrocities against imperial supporters.

In late 1931, with the Gaullicans coming under immense pressure in Euclea, it was forced to redeploy forces to the Euclean mainland. The Etrurians with forces spare from its fronts in Euclea, redeployed 35,000 soldiers and launched a series of amphibious landings behind Gaullican-PRRC lines at Bandar-e Hassan. Advancing from there, the Etrurians also launched a counter-attack from northwestern Pardaran, pushing the Entente back. The PRRC would be pushed back south of Zahedan, to the point of only holding territories immediately north of Jozdar, Esfarayen and Soltanabad. There, the Etrurians held their positions, to focus on evicting Gaullica out of Badawiya. This front would remain static until the end of the Great War in 1935.

With the end of the war, the Etrurians secured the complete withdrawal of Xiaodongese forces from Pardaran, but unwilling to prolong its war footing, and under immense domestic pressure to bring troops home – Etruria signed a general ceasefire with the PRRC, accepting a de-facto PRRC led territory in the far-south. This ceasefire would last until 1939, when hostilities resumed with the Etrurian Revolutionary Republic launching Operazione Aquila.

Solarian War

Between 1935 and 1938, the PRRC consolidated its hold over the southern strip of Pardaran it retained from the Great War. Dubbed Balasagan, the PRRC focused on preparing for a future conflict with Etruria and imperial protectorate, training and arming a significant portion of the male population under its control. Yet, the PRRC also built new schools and hospitals as a means of shoring up popular support. No negotiations had been held with the Etrurian government since the end of the Great War, impeded further by the Legionary Reaction and the establishment of the Etrurian Revolutionary Republic in 1936.

Following the establishment of the totalitarian far-right regime in Etruria, the new government vowed to restore order to its overseas territories in preparation for avenging the Great Betrayal. In the years leading up to 1938, the Etrurians deployed an estimated 180,000 soldiers to Pardaran to re-establish colonial control over Balasagan. On 2 July 1938, the Etrurians launched an invasion of Balasagan, decimating the PRRC’s first line of defence.

With the Etrurians advancing quicker than anticipated, the PRRC leadership retreated to bunkers and entrenched positions in the Saghand Ridge, where it directed a transition from conventional fighting to guerrilla warfare. The Etrurians restored direct control over Balasagan by November. The PRRC would wage a guerrilla war in Balasagan and sporadically in other parts of Pardaran throughout the Solarian War. A turning point came in 1945, when uprisings in Etruria’s colonies in Hyndana, alongside its collapse in Euclea enabled the PRRC to attack out from Saghand, toward the southern cities and ultimately Zahedan. The war’s end in 1946, denied the PRRC the ability to reach Zahedan, with its advances blunted by the deployment of Imperial Army units.

The history of the Ali Sattari led resistance since 1918, was one of near triumphs and successes, but ultimately denied by external events or military defeat. However, the PRRC had at its disposal one of the most experienced, disciplined and cohesive fighting forces in the world. Having fought near-uninterrupted for 28 years, it was at a significant advantage compared to the Imperial military. The near three-decades of rebellion and resistance resulted in Pardarian society becoming highly agitated toward foreign domination, interference and conflict. The consecutive wars which saw independence denied by other nations and the compliant Shah sowed the seeds for further rebellion against the Shah and his regime.

Following the Solarian War, Etruria's colonies were granted independence by the Community of Nations through the Treaty of Ashcombe, signed in mid-1946. Unable to find a suitable authority for a future Pardaran and seemingly accepting of the Shah's assertion that he could govern Pardaran as a close ally of the eastern Euclean states, the Shahdom was transferred control of all Pardarian territory as defined by the 1863 Etrurian border. Etrurian Badawiya was granted independence, along the same demarcations. The PRRC immediately rejected Imperial governance and vowed to overthrow the monarchy and govern Pardaran in its place.

Imperial control would rapidly prove illusionary within months of independence, with the PRRC launching attacks against the Shah to expand its area of control. Two highly charismatic and popular former Imperial figures, Khosrow Shamshiri and Hatami Ali Rasfanjani establishing their own fiefdoms in the northwest. The collapse of Etruria's colony of Cyracana led to the establishment of the Ashkezar Republic in the northwest region. By the end of the year, the Shah was further away from ruling a reunited Pardaran than at any point since 1863.

Factions

Shahdom of Pardaran

On paper, the Shahdom of Pardaran was not only the most powerful state in relation to its Pardarian rivals, but one of the most powerful to emerge out of the Great and Solarian Wars period. It possessed a large field army of over 500,000 soldiers, with modern weaponry and the international backing of the Community of Nations and numerous Euclean states. The discovery of oil in the Pardarian desert in 1922 provided significant potential to the country. However, from the onset of the civil war, the Shahdom faced significant problems.

The greatest hinderance to an imperial victory and the unification of Pardaran under the Shah, was the Shah himself, but also the Shahdom as a state. Since 1860, the Shahdom had existed as an Etrurian colonial protectorate, in which the Shah swore fealty to Poveglia, in exchanged for some degree of autonomy. From 1880 onward, the Shahdom became widely derided as powerless, corrupt and inefficient. Regular Etrurian abuses would be unanswered and Pardarian economic interests were subordinate to those of Etruria. Noted historian Mohammad Nadenidinejad wrote in 1955, “the Shah to millions was a coward, a traitor and a man who valued the Etrurian more than the Pardarian. He talked patriotism, but we knew it was a lie.” In fact, the Shah's legitimacy crisis played a key role in the dismemberment of the country post-independence in 1946, seemingly lacking the authority to cement centralised control.

Confounding the political weakness around the Shah, was his late decision to break from Etruria during the latter stages of the Solarian War. In 1945, just three months before the war's end, Ahmad Reza Shah proclaimed Pardarian independence, the forces under his command saw little resistace by Etrurian colonial forces, most of whom had been withdrawn to the Etrurian mainland. Not only did Pardarian colonial troops play a limited role on side of Etruria during the conflict, those who did see combat experience against the PRRC in the south were either later killed or incapacitated toward the war's end. The Shah's defence of the Etrurian colonial system against the PRRC resurgence during the 1940s, and then his belated separation fuelled popular opposition to his rule. Ahmad Reza was widely derided as "greedy, corrupt, shifty and inept" according to historians. This perception not only found purchase in the south, but even within his own court.

Militarily, the Shahdom on paper was at the advantage, in reality, it was poorly led and bloated with officers who secured their position through patronage over experience or ability. The most capable imperial commander, General Omid Dehghan was assassinated by a PRRC agent in December 1948, a significant blow to any "chance of imperial reorganisation." The officer corps of the Imperial Army was so poorly organised and inept, that in some cases, senior commanders were unable to differentiate between unit sizes, while one instance recorded a commander struggling to read a map of the local area. Prominent historian, George Miller wrote, "the Imperial Army was crippled from the onset by its officers, most of whom received their ranks and titles through patronage, or outright bought command positions from the imperial court. Most had never served, nor trained, they were just handed a uniform and a battalion or division."

However, arrayed against its opponents was an Imperial Army consisting of 500,000 soldiers, armed with modern weapons seized from Etruria and provided by its Euclean supporters. It also possessed up to 200 light tanks and half-tracks, the Imperial Pardarian Air Force had 95 aircraft, 50 of which were realtively modern fighters imported from Estmere.

Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command

The PRRC first emerged during the Great War as a Xiaodongese backed and supplied resistance movement against Etruria. However, many of the PRRC's officers and leading figures were involved in the earlier failed Pardarian uprising (1920-1923), led by Hussein Gholafdar. The high level of support in training, arms and political assistance, resulted in the emergence of Seven Pillars ideology. The ideology drew many components from Xiaodongese nationalist theories and traditions.

The PRRC, also called "Sattarists", "nationalists" —feared permament national fragmentation and opposed the separatist movements and Shahdom in equal measure. They were chiefly defined by their anti-monarchism, which galvanised diverse or opposed movements like leftists and democratic republicans. Their leaders had a generally more firmer ideological disposition, more combat experience and came from predominately poor backgrounds.

The PRRC side included the Sattarists, but also a collection of leftist groups who aspired to emulate Swetania, anti-monarchist liberals and pro-Pan Zorasani minorities. By the end of the civil war, the PRRC would have purged most of the non-Sattarist elements operating under its military command. Virtually all groups under the PRRC had strong Irfanic convictions and supported the native Pardarian clergy, aided by the anti-clerical actions of the Shah and warlord territories. The PRRC included the majority of the Irfanic clergy and practitioners (outside of the Ashkezar region), the support of the Irfanic Kholofah would play a major role in the PRRC's victory, with Supreme Custodian Payam Ali Bandari declaring a fatwa against the opponents of the PRRC in 1948 galvinising popular support. While the PRRC would ultimately establish a nominally secular state following its victory, its ties with the clergy and the resulting religious fervour that aided PRRC forces would entrench the clergy's new influential political role post-war.

The PRRC's military forces at the start of the war were highly experienced and well motivated, though limited in firepower. Of the 150,000-200,000 soldiers it possessed in 1948, only 5,000 were armed with the latest sub-machine guns that emerged in the Great War, while the remainder were forced to rely upon aged bolt-action rifles, some dating as far back as the 1910s. The PRRC lacked significant number of artillery, having centralised its howitzers into two artillery battalions. The vast majority of artillery in use by the PRRC in the early phase of the war were limited to mortars, raging from 30mm to 80mm. The capture of the Erfanshahr Arsenal in November 1948 secured the PRRC more modern weaponry and over 300 field howitzers. Despite the lack of modern weaponry, the PRRC held a significant advantage in strategic and tactical planning and thinking, its forces were highly motivated and well-supplied with ammunition and other materiel.

Other factions

Ashkezar Republic

The origins of the Ashkezar Republic lay with the multi-ethnic pro-democratic independence movement within the boundaries of the Etrurian colony of Cyracana. The Etrurian dismemberment of the Gorsanid Empire saw Cyracana emerge as the most economically developed region of Pardaran, owing to its large deposits of coal and metals. The region was also more evenly divided between the Adari, Harian and Pasdani ethnic groups. Cyracana also was notable for the more cosmopolitan approach to governing by Etrurian colonial authorities, compared to the often more racialist approach seen in other regions of Colonial Zorasan.

As the Etrurian Colonial Empire began to collapse during the later half of the Solarian War, pro-independence movements inside Cyracana rallied around the Ashkezar Free Movement, led by the poet, academic and economist, Salatyn Irevani. During the Solarian War, resistance to the continued Etrurian presence was sporadic within Ashkezar, while civil disobedience and peaceful protest grew significantly under the leadership of the AFM and Irevani.

Ultimately, the final collapse of the Etrurian government in 1946 led to the declaration of an independent republic by Salatyn Irevani. Using his academic ties to Euclean countries, he succeeded in securing meetings with diplomats from the Community of Nations in order to garner international recognition. While initial responses were positive, the CN’s decision to grant Pardarian sovereignty to the Shahdom devastated Irevani and his leading associates. The collapse of the Shah’s authority and the emergence of territories to the south, led by aspiring warlords effectively guaranteed de-facto independence. Elections and a constitution were held and produced respectively by January 1 1947.

Ashkezar with Irevani as President saw an opportunity to rapidly seek out international recognition and backing to protect its nascent democratic system from the Shah, who had vowed to restore imperial control over all Pardaran on December 29. By the outbreak of civil war in 1948, the Republic had succeeded in garnering recognition some XX, XX and XX. The support of these countries was key in aiding the fledgling Ashkezar Armed Forces fending off attacks from both the Rasfanjani and Shamshiri Cliques. However, despite its best efforts, the AAF lacked sufficient talent for officers and while it possessed significant weapons and materiel from the Etrurian collapse, its soldiers were poorly trained and rarely exceeded the quality of a popular militia. During the final stages of the war, the AAF were highly motivated and resisted fiercely, it would prove unprepared and unable to resist the organised offensives by the PRRC.

International support

Shahdom

With the Imperial government being recognised as the sovereign authority over Pardaran as a whole. However, the swift collapse of imperial legitimacy and control between 1946 and 1947 resulted in much of the initial support and goodwill vanish seemingly overnight. The only major world government to remain steadfast in support for the imperial government, was Estmere.

Estmerish support was mostly focused on supporting reconstruction in exchange for lucrative business contracts and expanding its commercial and political influence. With the outbreak of war in 1948, Estmere began to dispatch convoys of merchant vessels to supply the Imperial Army with rifles, artillery, tanks and ammunition. As Imperial losses rose dramatically throughout 1948 and 1949, these convoys increased in turn. Efforts by Estmere to dispatch officers to assist the Imperial Army were repeatedly blocked by the Shah’s inner circle, many of whom feared that introducing a colonial power would further fuel rising support for the PRRC, but others also feared loss of position and status.

Following the Fall of Zahedan in early 1949, Estmerish support began to decline as confidence in the Imperial government began to collapse. Estmerish merchant ships were provided for the evacuation of civilians from the siege of Bandar-e Hassan.

The Shah also received support from neighbouring Amardia,…

PRRC

Ajahadyan Involvement

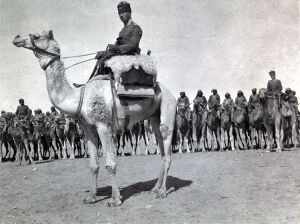

Fresh out of the Solarian War and the First Satrian War, the Ajahadyan government had little desire for a large-scale official intervention, and supporters of intervention were limited to Arjuna Kalsarah who had previously commanded a small unit of volunteer cavalry during the Pardarian uprising in the early 1920s and knew several leaders of the PRRC on a personal basis. Despite their lack of desire to intervene, Jalender Sarai, fearing what Kalsarah, known to be short-tempered and unruly with little taste for governance or peace, might do within Ajahadya if left unoccupied, ordered him to lead an intervention force through Kituk on August 9th 1948.

The Ajahadyan Expeditionary Corps, numbering some 22,000 men, mostly cavalry, was formed from Kalsarah's pick of regiments and was formed mainly from battle-hardened units commanded by veteran officers, many having fought in the Great War, Ajahadyan Civil War, Satarian Insurgency, Solarian War and the First Satrian War. Many former Green Pardal and Azad Fauj soldiers also numbered among its ranks. Ajahadya also supplied the PRRC with small arms and ammunition through the Kalsarah Caravan, a camel route through Kituk to Soltanabad.

Xiaodong

The PRRC’s ties to Xiaodong stretched as far back as 1918, when it was first formed by Mahrdad Ali Sattari. The Xiaodongese, eager to see Etruria expelled from Coius, supplied the PRRC with weapons, ammunition and other supplies throughout the Khordad Rebellion. Following the PRRC’s defeat in 1922, the senior leadership of the PRRC fled to Xiaodong in self-imposed exile. While in Xiaodong, the PRRC leaders received training and further monetary support from their Xiaodongese patrons.

The ideology of Sattarism is widely credited to Xiaodong’s National Principalism, with both sharing stark similarities and commonalities. This ideological connection would further cement ties between the PRRC and Xiaodong, and later form the basis of the Rongzhuo-Zahedan Axis. With the outbreak of the Great War, Ali Sattari and his allies returned to Pardaran to rebuild the PRRC, this time with significant backing from Xiaodong. The role of the PRRC-Xiaodong operation in Etrurian Pardaran was key in consolidating the PRRC’s territory in the south.

From 1946 to 1948, the Xiaodongese continued to funnel rifles and supplies to the PRRC through the Khakestar Corridor. With the Imperial government unable to strike the valley road, they were also unable to halt its dramatic modernisation and expansion. Throughout the civil war, the PRRC and Xiaodong constructed new roads, two railroads and mountain-side corniche roads, dramatically increasing the materiel the PRRC could receive.

By the Civil War’s end in 1950, Xiaodong had supplied an estimated 350,000 rifles, 20,000 machine guns and 1,200 pieces of artillery. Notably, Xiaodong also supplied the first aircraft that be the foundations of the Zorasani Irfanic Revolutionary Army Air Force. An estimated 12,000 Irfani Duljunese also served in the PRRC’s forces, having volunteered from Xiaodong. In return for Xiaodong’s largesse, the new government constructed a new pipeline through the Kharkestar Corridor by 1953, which was used to export oil at greatly reduced prices.

Preceding events

Northwest Pardaran

Throughout 1947, intermittent clashes erupted between the territories of the Shamshiri and Rasfanjani Cliques, while both also launched sporadic attacks against the Ashkezar Republic. In most cases these sporadic attacks were nothing more than raids against economic targets, or efforts to seize territory as the three factions sought to consolidate their holdings.

Throughout the Spring of 1947, the Rasfanjani Clique made repeated attacks to breakthrough Ashkezari lines to threaten Mazdavand, in doing so, Hatami Ali Rasfanjani hoped to secure control over the Republic’s lucrative metal ore deposits, while the Rasfanjani Clique made efforts to secure the coastal town of Bandar Hussein to seize the large Etrurian-built arsenal. In all cases, the Ashkezari Army held its positions, aided by terrain and the poor quality of Clique forces.

By Summer, attempts at a marriage of convenience between the two Cliques fell apart, leading to bloody clashes. The costliest was the Battle of Farfar Pass in October 1947, where over 10,000 soldiers were killed on both sides. Both sides sought to cripple the other, while the Rasfanjani Clique sought to alleviate its supply problems by capturing the port city of Chaboksar. Neither side secured victory, while the Shamshiri Clique held control over the strategic mountain pass to the coast. The losses in manpower and materiel effectively destroyed both factions’ offensive capabilities and would play key roles in their eventual and rapid collapse before the PRRC in 1950.

The victories against the two warlords, granted the Republic much needed combat experience, while it also improved public morale. President Salatyn Irevani sought to publicise the victories to further aid his government’s pursuit of international support and recognition.

Unrest in the Shahdom

From the Treaty of Ashcombe that granted Pardaran its independence, the Shahdom had been gripped by popular unrest and political infighting, owing to the Shah’s lack of public support and his legitimacy crisis. Throughout 1947, the Shah and his allies were forced to concentrate solely on protecting their positions of power from internal threats. The Shah’s focus on defeating plots to usurp his crown, confrontations with the urban working class and clashes with the Irfanic Clergy denied his government the much-needed time and space to organise and prepare its forces. The internal instability is widely claimed to be a key cause in the collapse of the Shahdom and the ultimate PRRC victory.

In the first few months of 1947, the Shah was forced confront the so-called Bazgard Plot. The plot centred around a group of local military officers who were supported by local merchants, who saw the Shah’s corruption as a threat to their financial interests, while the officers feared his inability to recognise the PRRC threat. The plot was foiled by rival merchants reporting the names of the plotters to the Imperial court. This was followed by a wide-raging purge of local figures in Bazgard, before ultimately extending to the entire imperial government.

The purges of early 1947 greatly unsettled the imperial government. The purges also led to the establishment of the Imperial Security Office (Aman-e Afsarshahree, AMAFSHA), this would eventually grow into the Shah’s feared secret police who would maintain strict imperial control over the home-front throughout the civil war. The purges also resulted in greater opposition to the Shah, as many aristocrats who lost power and status plotted his overthrow, further perpetuating the internal instability throughout the civil war.

On August 19, the Shah personally signed the death sentences of 20 former court officials and civil servants. All 20 were later publicly executed in central Zahedan before a large crowd, rather than instil fear as intended, the public affair only further alienated the Shah from his subjects. The August 19 Executions also provided a propaganda coup for the PRRC, who depicted the Shah as a “bloodthirsty tyrant.”

By the end of the year, the Shah had removed the most serious threats to his reign, but in doing so, had alienated segments of society that would have been central to a viable strategy to resist the PRRC and ultimately unify Pardaran under the monarchy. One segment was the Irfanic clergy, his excessive use of violence against threats real and perceived was proving a sore point in his relations with clerics. By mid-1947, many Irfanic clerics were speaking out against the Shah, his family and government, leading to a crackdown by the ISO in early November. The crackdown led to the deaths of up 86 clerics, finally breaking the clergy from the monarchy, with the Supreme Custodian Payam Ali Bandari issuing a fatwa against the Shah on January 20 1948.

Kumuso-PRRC conflict

Imperial-PRRC clashes

Clashes between the Shahdom and the PRRC were commonplace during and immediately after the Solarian War. Following the Treaty of Ashcombe, the clashes intensified as the PRRC’s forces advanced northward in a clear landgrab. The capture of Erfanshahr by the PRRC in late 1946, followed by the capture of Qazan Chay in March 1947, secured the PRRC vital territory from which to threaten the imperial capital of Zahedan. The loss of these cities were worsened by the loss of over 15,000 soldiers, killed, injured or captured, while in turn, Erfanshahr offered the PRRC control over 350,000 new citizens.

From 1947 onward to the outbreak of the civil war, the Shah would dispatch forces to make probing attacks toward both cities, in the eventual hope of reclaiming them. In virtually every situation, these probing attacks would be repulsed, often with heavy imperial losses. Elsewhere along the front, skirmishes and raids by both sides would be a regular occurrence, while the PRRC was renown for conducting atrocities against imperial soldiers and civilians. On September 19 1947, the PRRC scored a major victory when it ambushed an imperial raiding unit, killing over 200 soldiers, including Colonel Amir Reza Zahedani, the nephew of Ahmad Reza Shah. His death struck the monarch personally and he would order a halt to raiding attacks for several months.

During the 1947-48 period, the PRRC would dispatch numerous agents, provocateurs and political cadres into the Shahdom to destabilise imperial authority and mobilise popular support behind-enemy lines. Most of these agents would focus on rallying the support of the poor, the peasantry and urban working class. The PRRC also made use of radio broadcasts, to send propaganda messages, aided by the support of the Irfanic clergy, these messages would be broadcasted inside Beytols and other shrines.

In August 1947, mass protests broke out in the eastern city of Darandash against the declining working standards in the city’s textile mills and factories. In response, the regional governor dispatched troops to the city to break the strikes and end the protests. In the resulting crackdown, the soldiers killed up to 30 people. The killings sparked riots, with the assistance of PRRC agents escalated into a full-blown uprising. The PRRC began dispatching weapons and soldiers by boat across Lake Bakhtegan to Darandash, arming civilians and organising them into armed cells. By the end of September, imperial troops had been expelled from the city and the cells began to advance into the surrounding areas.

The Darandash Uprising soon saw farmers and peasants join the pro-PRRC rebels, capturing a swathe of territory along the shore of Lake Bakhtegan. Through to the outbreak of the war, the PRRC would dispatch flotillas of small vessels and barges to Darandash to reinforce its position, while also using its territory to receive arms shipments from smugglers based in the Kexri Republic. An attempted offensive by the imperial government to retake the PRRC enclave was repulsed with the loss of over 4,000 soldiers between December and February 1948.

From February through to April, repeated skirmishes would continue, while the Imperial Pardarian Air Force conducted its first ever air raid on Qazan Chay on February 21. 13 bombers launched an attack on the city’s railway station, the bombing kill 111 civilians and forced the PRRC to seek aircraft from its allies in Xiaodong. The PRRC’s Revolutionary Resistance Air Corps (RRAC) was formed on April 25, with a collection of ten fighter aircraft and four bombers.

Course of the War

1948

Utilising the distraction of the PRRC’s foray into Kumuso, the Shah ordered the Imperial Pardarian Army to organise and prepare for a major offensive aimed at retaking Qazan Chay, Erfanshahr and Baghan. Planned for April, the original plan lay within the Shah’s ambitions, but belatedly the Shah expanded the plan to include the capture of Kharandagh.

Between January and April, the IPA had amassed 186,000 soldiers and organised them into three Armies (1st, 2nd and 4th). These were commanded by the Shah’s son and heir, brother-in-law and university friend respectively. Though all three men had previous combat experience and commanded units before, none had commanded such large forces nor conducted a multi-force operation against an entrenched and prepared enemy. The PRRC had become aware of the imperial build-up through its network of informants and spies imbedded within the Shah’s government.

On 10 April 1948, the IPA launched Operation Amir Reza, striking toward three directions; Qazan Chay, Erfanshahr and Baghan. The offensive quickly stalled as the IPA faced entrenched PRRC positions, repeated attacks saw the IPA reach the outskirts of Qazan Chay by July, before being beaten back to the former border. By June, the offensive had collapsed, and the IPA was forced on the defensive, while the PRRC’s Black Hand Forces conduct guerrilla style attacks on imperial rear areas.

In May, the Rasfanjani Clique launched a small-offensive aimed at taking the agricultural region based around the town of Khargushi, by the end of the month they had secured the region, alleviating the food-shortages gripping the Clique’s territory. In June, the IPA’s 22nd Division launched a counterattack and evicted the Rasfanjani forces by early August, not before the Clique had burnt most of the fields and villages.

In July, the PRRC’s Mobile Strategic Corps, comprised of elite camel and horse-based troops launched a surprise attack on imperial forces northeast of Baghan, breaking through, they used their mobility and the southern reaches of the Dasht-e-Aftab desert to swing west and then south, encircling over 35,000 imperial troops around an area known as the Gur Band hills. This was followed by a large general offensive in the east by the 2nd Banner Army which tightened the encirclement and destroyed two-divisions as they were overrun.

In late July, the PRRC launched the full-front offensive dubbed Operation Khordad aimed at breaking the IPA’s lines. The operation would last until December, it would prove a decisive victory for the PRRC, with dramatic losses inflicted on the Imperial Army at the Battle of Goriyan, Battle of the Ardakan Road, Battle of Javadabad, the Fall of Namrin and the Battle of Mount Lavasan. The Baghan Pocket would be destroyed on November 19, with over 20,000 Imperial troops killed and 10,000 captured. The PRRC’s victory at Mount Lavasan, opened the way for the encirclement of Zahedan, forcing the evacuation of the Shah, Imperial Family and Court to Bandar-e Hassan. The Siege of Zahedan began on December 10 and would last until March 4 1949. In December, the PRRC also launched Operation Defah aiming for the capture of Sandsar, however, the Imperial Army scored its only major victory with successful defence at the Battle of Ashtian.

The causes of the rapid collapse of the IPA during Operation Khordad remains widely debated to this day, though the mainstream view is that the high levels of patronage and poor quality of officers denied the Imperial Army the required leadership and strategic thinking to manage such a large fighting force against a highly motivated and relatively mobile adversary. However, the collapse dramatically damaged the Shahdom and the Shah personally, with the loss of the capital to encirclement and the densely populated Zahedan-Namrin region, stripping the imperial government of its support base and most economically developed area. The IPA also suffered a catestrophic loss, when General Omid Deghan, its most capable commander was killed in the bombing of Hotel Saffron in the southern city of Mencharan. He was days away from the Shah appointing him supreme commander of the Imperial Army to declassified files. The bombing killed 90 other officers and commanders, decapitating the Imperial Army's command in the east.

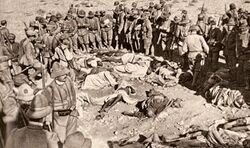

Throughout December, the PRRC conducted numerous purges and mass executions of suspected monarchists within the territories its gained. The largest took place east of the holy city of Namrin, where it executed an estimated 1,900 professionals, merchants and city officials. The PRRC would also execute an estimated 10,000 Imperial POWs during Operation Khordad, arguing they’d become a “fifth column of traitors” following its “inevitable victory.”

1949

At the turn of 1949, the Imperial Army was struggling to recover its organisation and cohesion in wake of its losses to the PRRC during Operation Khordad. With over 100,000 dead, injured or captured, it had lost an estimated 20.28% of its fighting force from April. It had lost hundreds of artillery pieces, most of which was abandoned to the enemy and thousands of rifles and modern submachine guns. Desertions were increasing and reports of officers abandoning their posts were covered up. The Imperial Army also suffered from 22,000 men being stranded in a pocket south of Ardakan, while a further 15,000 were under siege in Zahedan.

Despite the serious losses, the Shah ordered his generals to begin immediate preparations for a counter-offensive. His orders were enacted by his generals, most of whom owed their rank and wealth to his patronage, though dissenting voices urging for a defensive posture were side-lined. The Shah’s government established itself in the port-city of Bandar-e Hassan following its evacuation from Zahedan.

The PRRC during the early weeks of 1949 focused on the siege of Zahedan. The Supreme Commander of the PRRC, Mahrdad Ali Sattari made clear in a radio broadcast, that in wake of Operation Khordad was now “readying itself to govern and unite the nation.” The PRRC’s Political Cadre was reorganised into the Pardarian Provisional Revolutionary Government. The PRRC also began to step up its rear area operations, with Black Hand agents assassinating hundreds of monarchists, civil servants, police chiefs, politicians and merchants. PRRC agents also began operations in the Rasfanjani and Shamshiri Cliques, targeting their elites and public figures. The PRRC entered 1949, by conscripting thousands of ethnic Duljunese into forced labour, to construct roads and railways through the Khakestar Corridor, which links southern Pardaran to Xiaodong. By expanding the transport links, the PRRC intended to increase the quality and quantity of materiel imported from its ally in the south.

Despite the occasional clashes and skirmishes, the northwest remained relatively calm. The Ashkezar Republic for its part had focused on building up its defences since 1946, while its government was deeply divided on whether to assist the Shah against the PRRC. The debate was finalised on January 8, when President Salatyn Irevani narrowly escaped assassination by a pro-monarchist in Mazdavand. The Ashkezari parliament voted to denounce the Shah and remain neutral in the conflict.

The frontline between the Imperials and PRRC remained static until April, with much of the fighting being concentrated around Zahedan and the Ardakan Pocket. In February, the PRRC launched an offensive against the trapped 22,000 Imperial soldiers near Ardakan, the pocket would collapse by the end of the month. In mid-February, the PRRC made coordinated assaults against IPA positions defending Zahedan, capturing the Districts X, XII, IX within days. Throughout March, the IPA struggled to hold its positions, while fighting devolved into bitter house-to-house urban warfare. Under intense pressure, facing food shortages and lacking support for the Shah, thousands of Zahedanis rose up attacking IPA soldiers, causing its lines to collapse. On March 2, Zahedan’s defenders surrendered to the PRRC, the next day, Ali Sattari and the senior PRRC leadership arrived and established themselves in the former Imperial Palace.

Between March and June, the PRRC would execute an estimated 8,000 people in Zahedan. Most of whom were known Imperial officials, but also thousands of suspected sympathisers, many of whom were denounced by neighbours or the working class. The PRRC’s troops looted the former homes and villas of imperial officials, while at least three palaces belonging to the Imperial Family were torched. The PRRC looted the Imperial Bank of Pardaran to fund its war effort.

Despite the loss of the Ardakan Pocket and Zahedan, the Shah continued to oversee preparations for a counter-offensive. Numerous units were merged or reformed with conscripts or former inmates. Following the fall of Zahedan, the Imperial government was forced to introduce press-gangs in order to replace its losses, which further alienated the general populace and further opened the public to PRRC agents and political cadres. These preparations significantly weakened the Shah’s ability to defend his remaining territory, the vulnerabilities in the front would be a key cause in the rapid collapse of the Shahdom.

Having resupplied and expanded its forces, the PRRC launched Operation Emad-ye Kheshm on April 5. The full-front offensive aimed to completely destroy Imperial forces and bring about the downfall of the Shah. On April 20, the PRRC’s 2nd Banner Army reached the southern front of the Rasfanjani Clique, cutting off Sandsar and over 65,000 Imperial troops from supply. On May 9, the PRRC captured Mencharan and linked up with its enclave around Darandash. The Imperial Army all but collapsed on May 20, after the PRRC captured Shahrdar.

In June, the Imperial Army fended off a failed coup by the Imperial Navy after a week of heavy fighting in Bandar-e Hassan. Mass desertions began to be reported across multiple units along the front, mass flights of refugees began, with hundreds of thousands fleeing for the coast. A well-organised counterattack by the Imperial Army’s 2nd Corps under General Hassan Hatami failed with heavy casualties (20,000-21,000 killed). The 2nd Corps subsequently collapsed in wake of the Battle of Zahrab in July. The Shah defeats a second attempted coup by disaffected officers on July 27.

On August 3, the Xiaodongese trained Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Air Corps conducts its first bombing raid against Bandar-e Hassan, killing 300-500 civilians and heavily damaging port facilities. This is followed by similar air raids on Narmashir and Bazgard. On August 6-8, the PRRC suffers over 18,000 dead in a hasty attack on Narmashir. The PRRC’s forces begin reporting supply shortages as the frontline exceeds its logistical capacity.

866 civilians are killed when their overcrowded train from Shahrdar to Bandar-e Hassan is attacked by a squadron of PRRC fighter-bombers. The incident is widely used by the Imperial government to rally its forces and populace. In September, Crown Prince Ali Reza forms the Imperial Defence Organisation (IDO), a militia comprised of the most ardent monarchists. The IDO would commit numerous atrocities against civilians, who are suspected of being pro-PRRC.

On September 16, the PRRAC conducts a second larger air raid on Bandar-e Hassan, killing 2,500 civilians and destroying hundreds of shanty buildings housing refugees. On September 18, the PRRAC officially destroys the Imperial Air Force in a one-sided air battle over Narmashir.

The PRRC launches the third phase of Operation Emad-ye Kheshm on September 21, it will last until October 26. The PRRC’s renewed offensive captures Narmashir on October 3, with the surrender of over 80,000 imperial troops. The PRRC kills an estimated 16,000 people, including POWs, monarchists and suspected sympathisers throughout September. The PRRC’s Deputy Supreme Commander, Farhad Mirza is killed in ambush by IDO militiamen north of Narmashir on October 18. PRRC units execute over 800 civilians in reprisal for the assassination. On October 20, the PRRC defeats the Imperial Army at the Battle of Karani Pass, inflicting heavy losses and opening the road to Bandar-e Hassan. All forms of organised resistance by the Imperial Army cease as the entire military collapses. The PRRC’s 56,000-strong 3rd Banner Army advances toward Bandar-e Hassan, reaching the city by October 23. Thousands of civilians take to boats, ferries and ships to escape the PRRC, while the city’s defenders abandon their positions. The 3rd Banner Army enters the city centre and despite resistance from the IDO, captures the city on October 26. On October 27, the Shah, his family and several ministers are captured attempting to flee Bandar-e Hassan for the Ashkezar Republic. The ministers, his wife and daughters are executed by firing squad and buried in unmarked graves, while the Shah and Crown Prince are killed and their bodies dragged through the streets of the city. Prime Minister Sadavir Kharempour, as the sole surviving member of the imperial government, declares an unconditionally surrender.

Final phase

In wake of the Imperial surrender, the Pardarian Revolutionary Provisional Government (PRPG) ceased all major operations in order to enable its forces to redeploy and recuperate. All that remained in way of total victory were isolated Imperial pockets of resistance, the two warlord cliques and the Ashkezar Republic. The speed and ferocity of the PRPG’s victory over the Shah had stunned the international community, with the fall of Bandar-e Hassan coming at a time that several figures in the Community of Nations were organising an offer for peace talks.

The capture of Bandar-e Hassan would further consolidate the PRPG’s superiority over its remaining rivals, with the mass import of materiel from Narozalica, Chervolesia and Swetania. The PRPG’s aid from Xiaodong had reached its zenith in 1949, with tanks, modern rifles and artillery pouring in daily through the Kharkestar Corridor. By the onset of its final offensive, the PRPG had over 800,000 soldiers conscripted from its territory, alongside over 200 aircraft and 400 tanks. Throughout the remainder of October, the PRPG redeployed its forces, while it further consolidated its control through the Estekham.

On October 31, the PRPG launched Operation Emad-ye Entesar. The operation’s objective was to destroy remaining Imperial resistance and to defeat the two warlord cliques, barring the direction into Ashkezar. The for the first phase, the focus was on the Imperial Remnants, against 385,000 PRPG troops, stood an estimated 50,000 exhausted and demoralised soldiers who’s Shah had been executed only weeks prior. The PRPG captured the southwestern city of Sandsar after only two days of fighting on November 5, this was swiftly followed by the Battle of Dehbarez, where 10,000 out of 11,000 defenders were killed either in combat or post-battle mass executions on November 9. The Siege of Bazgard began on November 10 and would last until December 28, where over 35,000 civilians would be killed and the 27,000 strong defenders would all be killed in the fighting or executed following the city’s surrender.

Concurrent to the Siege of Bazgard, the PRPG’s 1st Banner Army launched its offensive against the warlord cliques, rapidly overwhelming the Shamshiri Clique, at the Battle of Pardaneh, Battle of Esfanjan and the Battle of Gamsar. The Shamshiri family successfully fled Pardaran by ship from Chaboksar for the Kingdom of Turbah. Their descendants would be executed by pro-Sattarist militants in 1962. The collapse of the Shamshiri Clique enabled the 1st Banner Army to launch attacks in the Rasfanjani Clique from the east and south, culminating in the Battle of the Zahrand Hills. The Clique’s defeat saw its total collapse as Hatami Ali Rasfanjani and his allies fled Khandabad on December 11, the Clique’s territory was finally taken in totality on December 19. The final Imperial holdout southwest of Moghul collapsed on December 31, with its 10,000 defenders surrendering to the PRPG. This marked the completion of Operation Emad-ye Entesar and saw the Ashkezar Republic as the sole surviving polity beside the provisional government.

1950

Following the collapse of the warlord cliques and the Shahdom, the PRRC opted to reorganise and resupply its forces for the offensive against the Ashkezar Republic. From December 1948 to May 1950, the PRRC’s forces were redeployed to the west, while smaller mobile units were established to mop up and crackdown on pro-monarchist uprisings and holdouts. During this time, the PRRC’s forces were massively modernised with important weapons, artillery, vehicles and personal equipment from abroad.

Equipment from Narozalica, Chervolesia, Xiaodong Ajahadya poured into the country through the ports seized over the previous year. The PRRC’s conscription of recently liberated populations saw its forces swell to over 800,000 strong by the time of the offensive against the Ashkezar Republic. The same period saw limited success by the AR to secure foreign weapons and materiel, however, it soon found that many in the international community had come to terms with the inevitable PRRC victory.

On 22 May 1950, the PRRC launched Operation Emad-ye Towheed with a heavy air and artillery bombardment of AR positions across the frontline. The offensive was conducted by the 2nd and 3rd Banner Armies that rapidly overrun the AR’s defensive positions. On June 6, the 3rd Banner Army captured Chaboksar, and besieged Bandar-e Hussein on June 10. In the far-west, the 2nd Banner Army saw more rapid advances, besieging Shul Abad by June 14 and destroying the AR’s 2nd Corps at the Battle of the Samanabad Canal on June 20.

On July 3, Bandar-e Hussein fell to the 3rd Banner Army that then proceeded north and northwest, besieging Bandar-e Parvadeh by July 14. The PRRC would suffer heavy casualties due to heavy and entrenched resistance, though the port city would finally fall to the PRRC by August 2. In wake of the city’s capture, one of the most controversial events took place, when the city was seemingly set ablaze by PRRC soldiers. In the ensuring firestorm, over 80% of the city was destroyed and an estimated 6,500 people were killed.

On July 26, elements of the 2nd and 3rd Banner Armies launched attacks on the AR’s capital at Mazdavand. Under intense artillery and air bombardment, the defenders quickly folded as morale collapsed. The PRRC rapidly advanced through the city, capturing Johmuri Square on August 3. Most of the Republic’s leadership had fled north to Borazjan, and would be forced to flee again when the city fell to the PRRC on August 4. The PRRC intercepted the last remants of the AR’s army and its leadership outside the town of Zamharir in the early hours of August 5. In the ensuing battle, the PRRC destroyed the last remnants of Ashkezari resistance, capturing hundreds of soldiers and the leadership of the Republic. At 18.00pm, PRRC leader, Mahrdad Ali Sattari proclaimed victory in a radio broadcast and announced that “Pardarian unification is now complete. Our destiny and fate now rest solely in our hands.”

The entire leadership of the Republic held in custody would be executed by firing squad on August 6, including President Salatyn Irevani. As the PRRC consolidated its control over the Ashkezar Republic, the Estekham was expanded and over 11,000 people would be killed by 1951 for playing senior roles in the Republic or opposing the PRRC’s unification of the country. Notably, the capture of the Ashkezar Republic ultimately led to the Adari genocide, as over 400,000 Adaris were killed or expelled from their homes and communities into Amardia.

Aftermath

Establishment of the National Pardarian Republic

Immediately following the collapse of the Ashkezar Republic, the PRRC set about establishing a new formal government over the newly reunified Pardaran. Having instituted the Estekham as the PRRC's territory expanded, by August 1950, a significant number of its opponents had already been killed or imprisoned. The proclamation of the National Republic of Pardaran was followed by the dismantling of all institutions across Pardaran, and the establishment of a single-party state through the PRRC’s Revolutionary Masses Party. The capital of the NRP was confirmed as Zahedan and the immediate focus of the new government was to consolidate its control.

For the remainder of 1950, the new regime expanded the Estekham, it initiated a repressive process against the losing side, a "cleansing" of sorts against anything or anyone associated with the Shahdom or other factions. This process led many to exile or death. Exile happened in three waves. The first one was during the First Phase (April-September 1949), followed by a second wave after the fall of the Ashkezar Republic (May-August 1950), in which about 500,000 people fled to Amardia. The third wave occurred after the War, at the end of August 1950, when thousands tried to board ships to exile, or fled into neighbouring Khazestan, although few succeeded.

Khazi Revolution

Throughout the Pardarian Civil War, its effects were acutely felt in neighbouring Khazestan. The PRRC’s use of mass radio broadcasts, alongside many former Khazi partisans having fought alongside the PRRC during the Solarian War, resulted in the establishment of the Khazi Revolutionary Resistance Command in 1947. The KRRC had limited ties to the PRRC owing to the lack of direct transport route, however, the KRRC adopted a Khazestan-centric iteration of Sattarism.

By late 1948, the concept of “Zorasan” emerged among the hardline-wing of the PRRC, this spread to the KRRC by early 1949. Upon the collapse of the Shahdom in late 1949, the KRRK and PRRC gained direct lines of communication, with the PRRC dispatching weapons and materiel to their Khazi counterparts. This led to the outbreak of political violence against the Khazi monarchy and the dispatching of political cadres across the rest of the country from its stronghold in Abbassiya. Following the PRRC victory in 1950, the KRRC’s support in materiel was increased and plans were underway to stage a simultaneous mass uprising with a Pardarian invasion from the west. In November 1950, the KRRC underwent a dramatic change of leadership following the assassination of its leader, Muqtada al-Qadr by the Khazi monarchy. His successor, Mustafa al-Kharadjiwas a staunch supporter of the “Pan-Zorasan” concept and reoriented the KRRC toward unification with Pardaran.

Although previously opposed to Pan-Zorasanism, Mahrdad Ali Sattari eventually came round following extensive discussions with al-Kharadji in the Spring of 1951. These meetings would prove vital in the eventual overthrow of the Khazi monarchy, the establishment of a KRRC government and, ostensibly, the unification of Pardaran and Khazestan. The unification of the two states would mark the beginning of Zorasani unification.

Victims

The number of civilian victims is still being discussed, with some estimating approximately 200,000 victims, while others go as high as 500,000. These deaths were not only due to combat, but also executions, which were especially well-organised and systematic on the Sattarist side, being more disorganised on the Imperial side (mainly caused by loss of control of the armed militias by the government). However, the 200,000 death toll does not include deaths by malnutrition, hunger or diseases brought about by the war.

Atrocities

PRRC

Sattarist atrocities, which authorities frequently ordered so as to eradicate any trace of "monarchism" and "subservience" in Pardaran, were common. The process known as the Estekham (استحکام; "Consolidation"), formed an essential part of the PRRC strategy, and the process began immediately after an area had been captured. According to historian Gustav Libermann, the minimum number of those executed by the PRRC is 100,000, and is likely to have been far higher, with other historians placing the figure at 250,000 dead. The violence was carried out in PRRC territories by the military, and popular militias known as the Brigade of the Opressed (Dāsteh-e Mostaz'afin). Abdullah Abdullah reports that the Sattarists killed 140,000 people during the war and executed at least 60,000 immediately after. The first few months of killings lacked much in the way of centralisation, being largely in the hands of local commanders, many of whom sought to secure approval from their seniors by "consolidating territories from reactionaries." As the war progressed, the PRRC's strategy for the Estekham changed, with the process now fully centralised, it opted to utilise locals for denounciations of supporters of the Shah and other factions.

The PRRC's focus was on population centres inside territory held by the Shahdom since the Colonial Partition conducted by Etruria in 1863. To the PRRC leadership, these urban centres and regions would hold the most loyal of imperial subjects and stood as a possible fifth column or threat in the future. The PRRC also targeted known aristocratic families, who's lineage traced far back to before the Etrurian arrival. Historian Hashim Abadi noted that, "the PRRC by 1951 had destroyed over 1,000 families who's lineage travelled as far back as the 1700s to the Imperial Court. Even the formerly high born were killed as possible threats."

Imperial held cities were also the focus of intense killing. PRRC forces massacred civilians in Goriyan, where an estimated 4,000 people were shot; 8,000 were killed in Zahedan; 10,000-15,000 people were killed in Namshir. However, the Estekham was not limited to territories taken from the Shahdom. Tens of thousands were killed in territories held by the warlords and the Ashkezar Republic. When Gamsar was captured, 3,000-6,000 people were killed, while 5,000-9,000 were killed in Khandabad. When the PRRC captured the Ashkezari port city of Bandar-e Parvadeh, 6,500 people died when the PRRC set the city ablaze in revenge for stiff resistance to their offensive. 7,000-11,000 people were killed in wake of Borazjan being captured by the PRRC.

It is widely considered that the Estekham was a key part of the PRRC victory as it allowed them to secure their rear. The PRRC had imposed a systematic and draconian violent order on the populace in their territory. They never suffered from serious partisan activity behind their lines and the fact that banditry did not develop into a serious problem in Pardaran, despite how easy it would have been in such mountainous terrain, is owed to the deep seated fear, the PRRC's death squads posed. This is in contrast to the imperial side, where it was unable to confront pro-PRRC guerillas or banditry which destabilise its rear area and undermined legitimacy.

Imperial

It is estimated that between 48,000 and 80,000 civilians were killed in Imperial-held territories, with the most common estimate being around 65,000. Historian Hashim Abadi estimated that the Imperial government executed 55,000 people. No exact figure for victims of the Imperial government can be certified due to both sides exaggerating the death toll. It is recorded that a vast majority of imperial victims were peasants, tenant farmers and members of the urban working class, who constituted the bulk of pro-PRRC elements in the Imperial rear lines.

Most atrocities committed by the Imperial government after 1949 were conducted by the Imperial Defence Organisation, established by Crown Prince Ali Reza in the same year. In the year prior, the Imperial Army was noted for its brutality against suspected PRRC sympathisers. In November 1948, the Imperial Army killed an estimated 3,000 peasants in the Gandar River Valley after a series of ambushes had disrupted Imperial supply lines. In December 1948, the Imperial Army killed 8,000-10,000 people for PRRC sympathies in Sandsar and its surrounding towns. As the PRRC advanced on Zahedan in 1949, the Imperial Army killed between 5,000-9,000 people in the city for being suspected PRRC supporters.

Throughout the 1948-49 period, the Imperial government relied upon Imperial Security Tribunals to try and execute suspected PRRC political cadres. Many of these executions took place in public spaces as a means of deterring PRRC action in Imperial held territory. Throughout the 1948-49 period, the Imperial government relied upon Imperial Security Tribunals to try and execute suspected PRRC political cadres. Many of these executions took place in public spaces as a means of deterring PRRC action in Imperial held territory. As the war turned against the Imperial government, the Tribunals began to fast-track trials, finding suspects guilty and sentencing them to immediate death. In one case, the IST in Bandar-e Hassan tried and executed 515 suspects in the space of one day.

In response to the 1948 Fatwa by Supreme Custodian Payam Ali Bandari, the Imperial Tribunals began to prosecute and execute hundreds of Irfani clerics for supporting the Supreme Custodian’s position. Throughout the 1948-49 period, an estimated 376 clerics were killed by the Imperial government, while an estimated 2,000 seminarians were also killed in a series of purges of the seminaries in Dehbarez and Sandsar.