Zorasani Unification

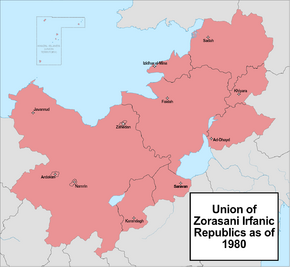

Zorasani Unification (Pardarian:انگلآب توحید; Towheed-ye Zorasāni; Rahelian:تَوْحيد الكرصانية; Tawḥīd al-Kurṣāniyyah), locally known as the Arduous Revolution (انقلاب دشوار; Enqelābe Sa'b;ثورة شاقة; Šāqq al-Inqilāb), was the military, political and social movement that consolidated different states of the Zorasan region into the single state of the Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics in the 20th century. The process began in 1946 with the Treaty of Ashcombe and was completed in 1980 with the formal unification of Irvadistan with the Union of Khazestan and Pardaran.

The origins of Zorasan’s unification process began in the early 20th century in response to the “collective trauma” of Euclean and primarily Etrurian colonialism and domination. The process’ philosophical and ideological inspirations were nationalism, republicanism, anti-colonialism and anti-imperialism and historical revisionism. Many early Zorasani nationalists promoted Pan-Zorasanism, claiming a shared nationhood between the peoples of the former Gorsanid Empire and its predecessor states as far back as the Rise of Irfan in the 320s BCE. This would evolve into a nationalism that viewed unification post-independence as the only viable means of averting the return of foreign domination and exploitation. These early nationalists through the Brotherhood Declaration saw the 2,302 years of co-habitation under a singular unified polity in one form or another, as evidence of a shared identity and nation.

The lack of divergent identities be they Pardarian or Rahelian further fuelled the rise of a “Zorasani nationalism” among the two distinct ethno-cultural groups. The 1910s and early 1920s also saw the emergence of the first form of Pan-Irfanism, where the shared religion was provided as reinforcement for Zorasani nationalism. Collaboration among Pardarian and Rahelian anti-colonial figures and intellectuals would prove decisive during the violence and destruction of both the Great War and Solarian War. Despite this, the collapse of Etrurian authority in wake of its defeat in 1946, led to the emergence of numerous independent states and civil war Pardaran. The Rahelian states to emerge fell to various tribal leaders assuming dominating positions and forming independent monarchies, while the Kexri-Rahelian region of Ninevah went on to form the Kexri Republic. The immediate failure of Rahelian monarchs to legitimise their rule, rebuild their shattered territories and the lack of a coherent Rahelian identity provided fertile ground for a grassroots embrace of Pan-Zorasanism. In 1950, the Pan-Zorasanist Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command defeated the Shahdom of Pardaran and established the United Republic of Pardaran under the leadership of Mahrdad Ali Sattari, the author of Sattarism, an ideology centred around the notion of a unified Zorasani state being the sole defence against resurgent Euclean influence. In 1952, the Khazi Revolution installed a Pan-Zorasanist government in Faidah, while northern Khazestan split as a monarchist holdout. The Pan-Zorasanist states united to form the Union of Khazestan and Pardaran, this watershed moment marked the beginning of the predominately armed struggle between the Pan-Zorasanist UKP and Rahelian monarchies.

Between 1950 and 1965, the two sides would struggle in both military, cultural and propagandistic confrontations, erupting into outright military conflict in 1965 with the Rahelian War. The Pan-Zorasanist victory in 1968, left only the Riyhadi Confederation and the Emirate of Irvadistan, though the latter fell to a socialist revolution shortly after. In 1974, a Pan-Zorasanist coup in Riyadha resulted in its annexation into the UKP, while the collapse of the balance of power ultimately led to the Irvadistan War in 1975, ending four years later with a final Pan-Zorasanist victory. After one year, on 1 January 1980, Irvadistan united with the UKP to form the Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics, ending the unification process after 34 years.

Zorasani unification is considered one of the most pivotal moments in the late 20th century, restoring a major regional power in Northern Coius for the first time in 120 years. It marked the culmination of three-decades of near-constant conflict and ideological upheaval. It marked the decline of Tsabara as the pre-eminent power in Rahelia and significantly changed the balance of power in Coius, in relation to the wider ROSPO-COMSED dichotomy, to the benefit of the former. The process was marred by atrocities such as the Normalisation and cases of ethnic cleansing and religious persecution. It is widely celebrated in Zorasan, which places greater emphasis on the process overcoming foreign interference and involvement.

Timeline

- 1841-1860 - Etrurian Conquest of Zorasan. Over the period of 19-years, the United Kingdom of Etruria and to a lesser degree, Estmere and Gaullica begin to infringe upon the territories of the Gorsanid Empire, which governed the near entirety of modern-day Zorasan since 1102 intermittently. The Etrurians utilising the economic, social and technological backwardness steadily seized control of the coasts and key port-cities, while also inspiring unrest through ties to various influential Rahelian tribal leaders. The Gorsanid Empire ultimately collapsed by 1858 in wake of the Fourth Etruro-Gorsanid War, leading to the Treaty of San Francesco, which dismembered the empire into Etrurian colonies and protectorates. The monarchy was permitted to exist as the Shahdom of Pardaran and under a protectorate of Etruria.

- 1910 – Republicanism and anti-colonialism begin to emerge in Pardaran as millions suffer in poverty and deprivation, while loyal Shah and the royal family engage in daily displays of luxury and comfort. The millennia old Pardarian monarchy begins to be seen as an institution for collaboration.

- 1912 – The Tabarzin is formed, led by a colonel in the Pardarian Royal Army, Mahrdad Ali Sattari. The Tabarzin include many Rahelians appointed to Pardaran by the Etrurian colonial administration.

- 1914-1921 – Khordad Rebellion. The Tabarzin instigates a mass uprising in the Shahdom of Pardaran with the aim of overthrowing the Shah and liberating Zorasan from Etrurian and Euclean control. Etrurian military superiority coupled with harsh reprisals and the use of chemical gas defeats the uprising, but its lasting legacy would inspire the Rahelian population and bring to public thought, the notion of Zorasan.

- 1928-1936 – The Great War. Etruria’s entry into the Great War is followed by a joint invasion of southern Pardaran by Xiaodong and the PRRC, smaller uprisings in Zorasani Rahelia take place, inspired by the previous Khordad Rebellion. Despite the defeat of Xiaodong and the Entente, the PRRC is able to entrench itself in southern Zorasan, capitalising on Etrurian exhaustion.

- 1942-1946 – Solarian War. Prior to the Solarian War, the Greater Solarian Republic, which overthrew the Etrurian Second Republic in wake of the Great War launches an offensive against the PRRC, sparking a third war in Pardaran. The GSR’s invasion of Estmerish colonies and its Euclean neighbours sparks a wider war. Aided by Xiaodongese materiel and Ajahadyan forces, the PRRC is able to beat back the Etrurians. The GSR’s collapse in Zorasan in early 1946 leads to the collapse of the Etrurian colonial order.

- 1946 – As Etrurian authority collapses, numerous local groups begin to carve out areas of influence. In Zorasani-Rahelia, the tribal leaders relied upon by Etruria for support assume power over the respective crumbling colonies, forming the Kingdom of Khazestan, Emirate of Irvadistan, while the tribal-merchant families of the Riyadhi peninsula unite to form the Riyadhi Confederation. In Ninevah, the League of Free Kexri in alliance with local Rahelians establish the Kexri Republic, while Pardaran collapses into chaos. The colony of Cyracana fractures into the Ashkezar Republic and two warlord cliques, while the PRRC skirmishes with the Shahdom of Pardaran.

- 1948-1952 – Pardarian Civil War. The PRRC led by Mahrdad Ali Sattari defeats its rivals and reunifies Pardaran.

- 1950-1951 – Khazi Revolution. Chronic instability, food shortages and internecine tensions among the Khazi elite leads to political instability, deepened by Pardaran. Mustafa al-Kharadji and the Khazi Revolutionary Resistance Command overthrows the monarchy. The revolution is swiftly followed by a Khazi intervention in the Kexri-Rahelian War in support of the Rahelian population - the region of Ninevah was long seen as part historic Khazestan.

- 1951-1952 - The Kexri-Rahelian War results in the overthrow of the Kexri Republic and the establishment of the Provisional Government of Ninevah.

- 1953 - The Pan-Zorasanist authorities in Pardaran, Khazestan and Ninevah unify to form the Union of Khazestan and Pardaran.

- 1953 - Facing the UKP threat, the monarchies of the Riyadhi Confederation and Irvadistan in turn unite to establish the Kingdom of Rahelia.

- 1953-1965 - A state of cold war emerges between the UKP and the Kingdom of Rahelia, involving terrorism, propaganda struggles and assassinations.

- 1965-1968 - Rahelian War breaks out between the UKP and the Kingdom of Rahelia, despite significant Euclean backing, both sides agree to end the war as a stalemate. A CN-mandated de-militarized zone is established to separate the two nations.

- 1968 - Irvadi Revolution, a socialist revolution in Irvadistan overthrows the Rahelian monarchy, this is later enforced in Riyadha culminating in the establishment of the United Rahelian People's Republic.

- 1975-1979 – Irvadistan War. Fearing a UKP invasion, the URPR launches a pre-emptive strike and invasion of northern Khazestan. Backed by MASSOR and the Communal Republic of Tsabara, the Irvadis inflict heavy losses on the unprepared UKP. However, the tide turns and the UKP begins to beat the Irvadis back, ultimately defeating them at the Battle of Sadah. The collapse of the IPR results in the establishment of a UKP-align provisional government and occupation.

- 1980 – Irvadistan formally unites with the UKP to form the Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics, ending the 34-year process beginning in 1946.

Background

Origins of Zorasan

The roots of the name Zorasan can be traced back to the Middle Pasdani "Xwarāsān", meaning "Land of the Sun." It was first used to denote the expanse of territories under the Arasanid Empire, when in 325 BCE, Shah Farrokhan II proclaimed his empire to be the "greatest expanse under the Sun" in a series of poems written in that year. His coining of the term was adopted by the First Heavenly Dominion during the Rise of Irfan, when the Prophet Ashavazdar, declared his intention to "free all Zorasan from the bounds of ignorance." The term from its inception until the Pardarian Civil War in the late 1940s, was rarely used to denote a singular polity, but rather a geographical region, under the Arasanids it denoted the imperial heartlands, which corresponded mostly to the modern boundaries of Zorasan, while under the Heavenly Dominions, "Zorasan" was used to denote the entirety of the Irfanic World, often due to the metaphorical comparison of the Sun to Khoda. Its relationship with the rise and spread of Irfan, alongside the definable boundaries of Zorasan provided by the Shahs enabled the term to become culturally and political engrained in both the Pardarian and Rahelian peoples.

Etrurian and Euclean colonialism

Throughout the middle-ages and early modern period, the Gorsanid Empire had engaged in a series of small, short conflicts with the predominately maritime nations of South Euclea, specifically Montecara and the Exalted Republic of Povelia. The decline and fall of Povelia during the Etrurian Revolution and the subjugation of Montecara under Gaullica, removed the most capable rivals to the Gorsanid Empire by the early 19th century. However, despite its capacity to defend its interests and territory, the Empire began to decline technologically, economically, and militarily. Its antiquated and autocratic monarchy opposed efforts at modernisation, wishing to preserve the interests of the landed agrarian elite, of which it entirely depended for support. Technological modernisation was also seen by the Irfanic religious establishment as a product of the Euclean enlightenment and thus a threat to its own power and influence. As the Eucleans began to see the first stirrings of the industrial revolution, the Gorsanid government shuttered institutions attempting to imitate Euclean advances, this would expand to virtually all areas of progress, including military strategy, organisation and equipment.

The Caltrini Restoration in Etruria, saw Etruria return to monarchical rule and with it came overseas ambitions as a means legitimising the new regime through glory, as well as opening foreign markets to Etrurian goods. The Etrurian gaze turning toward the decaying and declining empire to the south was also in part driven by Gaullica’s rising colonial activities in Tsabara.

In 1832, a trade delegation was dispatched to Zahedan to discuss the opening of Gorsanid ports to Etrurian goods, purportedly with the intention of proposing a mutually beneficial arrangement of Etruria importing Gorsanid cotton and fabrics in exchange for Etrurian weaponry and for the port of Chaboksar being leased to Etruria where a trade office would be permanently placed. Not only was the delegation denied an audience with either the Shah or his ministers, they were attacked by bandits during their return journey to the coast, leaving Conte Giacomo di Tarandella, a personal friend of King Caio Aurelio II dead. The perceived insult coupled with the bandit attack led to Etruria demanding a financial package in compensation, which was rejected. In late May 1832, the Etrurian Royal Army and Royal Navy attacked the port of Chaboksar, occupying the city and proclaiming it Etruria’s compensation. The Shah’s counterattack was crushed by the superior Etrurian force and the Shah, fearing further defeats acquiesced. In celebration, the city was renamed to Assoluzione (Absolution). The 1832 incidents marked the beginning of the steady encroachment of the Empire by Etruria, and later Estmere and Gaullica. Utilising the divisions within the Gorsanid court to undermine the Shah’s authority, while capitalising over localised disputes and events to wage ever wider wars, resulting in large tracts of the Empire being ceded to Etruria, the Gorsanid dynasty would eventually collapse in the 1850s.

In 1856 following the final war between Etruria and the Gorsanid Empire, the Treaty of Povelia finalised the demise and colonial subjugation of the Gorsanid state. The results would dramatically transform the region for decades to come. Western Pardaran was ceded to Etruria as the Dominion of Cyracana (Dominio di Cyracana), the eastern half of the Empire (modern day Khazestan, Riyadha and Ajad) were ceded to Etruria, becoming the Dominion of Etrurian Rahelia (Dominio di Rahelia Etruriana), the Ninevah region to the east, would be placed under a protectorate known as Ninavina, where the Etrurians relied near exclusively on Kexri elites to govern on their behalf, laying the foundations for the future Kexri Republic. Modern day Irvadistan was partitioned between Rahelia Etruriana and Gaullica’s Hamada colony in the early 1860s following a colonial incident. While southern Pardaran and the “Zahedan Corridor” was to remain under the rule of the continued Shahdom, though it would fall under Etruria as a protectorate. The Shahdom would be permitted to maintain a small, Etrurian officer-led military force, and surrender its economic and foreign policy to Etruria, effectively turning the millennia-old Zorasani monarchy into a puppet-state. The Shah’s wealth and personal freedom would be guaranteed, though Etruria would be granted an influential voice on succession. And the Irfanic establishment would be left to operate as it had done prior without interference.

Hassan Reza Shah who signed the Treaty of Povelia abdicated shortly after and would later commit suicide, succeeding him was his nephew, Hushang Ali Shah, who was the preferred candidate of Etruria. Ali Shah’s ascent to the throne established the Zarafshanid dynasty, which would rule the rump of the Zorasani state until 1950, when Ahmad Reza Shah was defeated and killed during the Pardarian Civil War.

For the next 90-years, the Etrurians would dramatically expand their control over their dominions and maintain a tight leash on its two protectorates. Etrurian companies and industrialists would exploit the Zorasan’s natural resources with abandon. Railroads, telegraph networks and factories were built for the sole purpose of supporting Etruria’s economic needs, being constructed at the expense of local communities and no regard for local sensitivities. Etrurian colonial authorities actively clamped down on the educating of local inhabitants and would regularly crackdown on the Irfanic clergy for using the Minbar as a means of agitating for resistance, this would result in the post-colonial states ranking among the lowest in the world for literacy. Uprisings and resistance between 1856 and 1914 were sporadic but dealt with harshly, with mass reprisals against entire communities being commonplace. The overthrow of the Etrurian monarchy in the San Sepulchro Revolution in 1888 did result in a softening of Etrurian rule, with the Second Republic instituting reforms that enabled the employ of locals to serve in colonial administrations, while they permitted local officials to transit Zorasan at will, providing a networking capability for literate and intellectual local elites, who in private sought to expel the colonial power.

Etruria’s use of tribal rivalries in Rahelia Etruriana specifically did little to assist its efforts in driving a wedge between the Rahelians and Pardarians, as it resulted in the Rahelians being forced to identify with their tribal name than the Etrurian propagated Rahelian identity. The utilisation of tribal leaders in Rahelia Etruriana would have adverse effects on the post-independence period and be the catalyst for the emergence of unpopular and poorly legitimised monarchies.

Etruria’s possessions in Zorasan would become battlegrounds in both the Great and Solarian Wars, where the use of local troops to defend Etruria’s control would prove pivotal in the awakening of a national consciousness, as in the Great War, Etruria propagandised the defence of “Zorasan” against the “yellow horde of Xiaodong.” There is a growing consesus among historians that Etruria's colonial administration served to plant the seeds of Pan-Zorasanism's success and the unification process, by both enforcing mass illiteracy and general ignorance of affairs beyond a person's local community and bestowing on the Rahelian population a greater affinity for their tribal group than their attempts at propagating a Rahelian identity. The Shahdom provided Pardarians the relative same situation, by abiding by Etruria's rule against fostering Pardarian nationalism and instead, centering the Pardarian existence around the Shah as the very embodiment of their society.

Pan-Zorasanism and anti-colonialism

Pan-Zorasanism had existed prior to the 20th century in limited forms under the Gorsanid Empire. In the furtive attempts to reform and modernise the state during the early stages of the Euclean encroachment, the monarchy had attempted to foster a unified identity as a means of better mobilising its large population. The Gorsanid dynasty made much use of the shared cultural, social and religious features of Zorasan to promote a singular identity to be adopted by both the various linguistic groups (as ethnicity or race was not recognised nor embraced in northern Coius in comparison to Euclea). The dynasty saw some success in establishing a shared view of Zorasan being a unifying entity, binding its peoples through a shared 2,300-year history, of peaceful co-existence, cooperation, and shared governance. The dynasty’s success in melding Irfanic history to the history of the Zorasani nation is considered to have been the primary root for the Pan-Zorasanism of the colonial period.

Abdolreza Bani-Etemad, a former courtier of the Gorsanid dynasty and one of the earliest ideological opponents of the Euclean colonial order, believed that history proved the innate fraternity of the peoples of Zorasan and that would eventually re-awaken to their identity and reclaim their country from the imperialists. He further claimed that the linguistic differences which had been irrelevant for 2,300-years would remain so and that the shared national consciousness of Zorasan would trump the new territorial reality, racialist divisions being perpetrated by the Etrurian colonial order and the period of time that would keep the nation divided.

Salim Serhan, Pešvā Serhan's "Zorasan Homily"

Until the emergence of intellectual nationalist groups during the early 1900s, the primary source for Pan-Zorasanist thought was the Irfanic religious establishment in Zorasan. The realities of the Gorsanid Empire upon its conquest by Etruria and other Euclean power was that literacy was restricted to only 15% of the population, notably the clerics and imperial administration. Therefore, the religious establishment had long been the repository for 2,300-years of historical record of Zorasani history dating back to the Rise of Irfan in the 320s BCE. This knowledge of history saw the colonial conquest leave an indelible mark on the clerical hierarchy, who saw the conquest both as the defeat of two-millennia long Irfanic rule, but also as a catastrophic failure of the Irfanic faithful, for permitting the fall of Irfan’s birthplace to non-believers. The view of the Euclean colonial conquest as a desecration of sacred soil mobilised the clerical elite into justifying resistance and restoration of the Zorasani nation on religious grounds. Between 1860 and 1900, the clerical elite had propagated and formulated Pan-Zorasanism as a religious obligation to evict the predominately Solarian Catholic colonial powers from the birthplace of Irfan, widely referencing “Xwarāsān” in the Roshangar, the holy text of Irfan, as the both the “fountain of faith” and the “gateway to heaven at the world’s end.” As most of the population were illiterate, the primary source for news and information was received from the Mazar and the cleric. The clerical establishments opposition to colonial rule and their propagation of Pan-Zorasanism as a religious obligation would prove invaluable in future decades, though while this would fail to produce a singular cohesive movement, it would embed within the wider social structure of Zorasan, an innate affinity for Pan-Zorasanism.

In 1904, Salim Serhan, a Rahelian Irfani cleric wrote a series of short homilies that were imbued with Pan-Zorasanist thought, the publishing works in Namrin distributed the homilies to clerics across Zorasan, enabling clerics to spread the unifying message. This marked the beginning of a decades-long role of the religious elite in support of Zorasani nationalist movements. One of the most pivotal moments in the early period of Pan-Zorasanism was a homily by the Custodian of the Faith in 1911, Nasrollah Ali Yadgari who said, what is Irfan without its roots and hearth united and free? What is Irfan with its birthplace of Zorasan sundered by the iron and fire of Euclean greed? His message was seen by millions of Irfani, who heard of its message through their local Peshvari, to be an endorsement of Pan-Zorasanism and resistance against Etruria and other Euclean powers. The following year, the Tabarzin, a Pan-Zorasanist movement was established by Mahrdad Ali Sattari and his message would be sloganised during the Khordad Rebellion.

The turn of the 20th century saw the expansion of Pan-Zorasanist thinking beyond the clerical establishment to many intellectuals serving in Etrurian colonial administrations. In Pardaran, where the monarchy maintained itself as a protectorate of Etruria, there was a rapidly growing class of educated officials, who privately balked at the state of affairs, though publicly loyal to the Shah and ostensibly his colonial overlords. These officials and intellectuals would go on to author Pan-Zorasanism as a motif for anti-colonialism, drawing inspiration from the clerical variety.

These individuals also took inspiration from the earlier Gorsanid attempt at fostering a nationalist identity, viewing Zorasan as a cohesive political entity rather than just a geographical area. They viewed every successive political entity from the Arasanid Empire (400 BCE) through the Irfanic Heavenly Dominions (300 BCE-1102 AD) to the Gorsanid Empire as one continuous thread of unity between the peoples of Zorasan. Mozaffa Annab, a leading Rahelian Pan-Zorasanist saw Zorasan as the inevitable result of the eviction of the Eucleans, regularly claiming Zorasan had existed before even the first organised Euclean state and would long exist after Euclea had faded into history as the centre of global affairs. Annab also saw Pan-Zorasanism as the ultimate weapon against colonialism and Euclean influence, "by uniting into a single polity, we shall have a polity that has withstood the test of time, but also be founded upon the rectification of past mistakes."

Mahrdad Ali Sattari, the most prominent Pan-Zorasanist figure during the first half of the 20th century repeatedly rejected the concept of Rahelia and Pardaran as individual and separate entities. He pointedly refused to identify himself as Pardarian and urged his followers to do the same, claiming such identities were Euclean constructs designed to entrench their enforced division of Zorasan’s people. He noted that different languages were spoken and oft repeated historic views that linguistics had failed to fragment the succession of Zorasani states. Although he was a secularist, Sattari drew significantly on the Irfanic variant of Pan-Zorasanism, declaring the relative religious homogeneity of Zorasan to be further evidence of an unbreakable relationship between the peoples of Zorasan that transcended the imported Euclean racial categorisation of humans.

Post-Solarian War states

The most decisive event leading up to Zorasani Unification was the Solarian War and the collapse of Etrurian authority across the entirety of Zorasan in early 1946. Facing rapidly advancing enemies within Etruria itself, the Greater Solarian Republic ordered a full-scale withdrawal of all forces in Zorasan, abandoning the Shahdom and its colonies. In the power-vacuum, numerous former clients of the Etrurian colonial order moved to establish themselves as the new power-centres. Within a matter of months, three monarchies would emerge out of Rahelia Etruriana; Emirate of Irvadistan, Kingdom of Khazestan and the Riyadhi Confederation. In former Ninavina, the Kexri colonial officials in support of the League of Free Kexri assisted in the establishment of the Kexri Republic. In Pardaran, the conflict between the Shahdom of Pardaran and the Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command denied both sides the ability to seize control of Cyracana, which fragmented resulting in the emergence of the Ashkezar Republic in the north and two regions south, subject to the rule of two former Cyracana Pardarian officers.

Almost immediately, the new states entered difficulty, primarily in dealing with the vast destruction and disruption caused by the Solarian War. Famine was widespread across the entirety of Zorasan, and the new regimes found themselves governing territories with virtually no public services, and near-total illiteracy. In every emerging nation-state, the Irfanic religious establishment was fragmented, despite an initial aim of promoting a confederation to reunite Zorasan. The potential for a settled reunification was dashed with the onset of skirmishes between the three Rahelian monarchies and the civil war in Pardaran.

The 1947 Treaty of Morwall which formally ended the Solarian War, granted international recognition to the Rahelian states, the Kexri Republic and the Shahdom of Pardaran. The Ashkezar Republic’s attempt at recognition was blocked by successful diplomatic manoeuvring by the Shah. The Republic joined the PRRC in being viewed as combatant factions in a civil conflict, rather than independent entities. The international recognition proved a boon for the monarchies and the Kexri Republic, as it enabled them to access reconstruction funds and assistance, however, this success would be undermined by the corrupt practices of the new monarchies. Simultaneously, the very same monarchies faced crises of legitimacy, as these leaders were descendants of families who accepted the Etrurian colonial authorities as patrons. The peasantry riled by clerics, were quick to see their rulers as collaborators and abettors of foreign occupation and decades of exploitation. This crisis of legitimacy was the same in Pardaran, where the Shah was denigrated by Mahrdad Ali Sattari, the leader of the PRRC as “the son of Etruria’s whores.” Republicanism spread throughout Pardaran, to such a degree that Pan-Zorasanism also became a struggle against monarchism in of itself. The PRRC during the latter stages of the civil war would vow to liberate Zorasan from the rule of puppets and collaborator monarchs, who’s ancestors provided Etruria the means to divide and rule the Zorasani people.

The post-independent states that emerged were from the onset significantly disadvantaged by their rulers and their decisions. The Khazi monarchy opted to focus on resource exploitation in the hope of tapping into oil reserves discovered during the early 1920s, to fund reconstruction. This focus prolonged food shortages and homelessness. No significant effort was made to build up public services, nor was any effort made to establish a unifying Khazi identity. The Riyadhi Confederation and Irvadistan proved more adept at recognising its immediate crises, though in the latter’s case, a failure to expand power and influence to individuals or groups beyond the Al-Mustafid family, resulted in unrest and numerous plots by rival families and non-royal power centres such as the future Irvadi Royal Army. The Kexri Republic, though initially democratic and inclusive, steadily saw the rise of the Kexri People’s Socialist Front, and marginalisation of the Rahelians. The KPSF’s desire to enforce a Kexri-dominant system upon its Rahelian population led to armed ethnic-conflict by the late 1950s. The Shahdom in Pardaran was disadvantaged by the growing military might and popularity of the PRRC and Mahrdad Ali Sattari. The Irfanic religious establishment’s long held aim of seeing the reunification of Zorasan for theological purposes gave way to considerable support for the PRRC, owing to it being the only major Pan-Zorasanist entity in wake of independence. The clerics denial of religious legitimacy to the monarchies and the propagation of PRRC slogans and ideals through the Mazar would serve the Pan-Zorasanist cause well, while exacerbating the tensions between ruler and subject.

Post-Solarian War period (1946-1953)

Pardarian Civil War

The collapse of Etrurian authority in Pardaran left a fractured and fragmented region in its wake, with multiple influential factions rising in the vacuum. The Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command led by Mahrdad Ali Sattari, and the Shahdom of Pardaran under Ahmad Reza Shah, being the two most powerful factions in western Zorasan had been locked in vicious fighting in the Gahvareh Basin since the Solarian War. Both factions sought to unify Pardaran under their respective regimes, though the PRRC’s ambitions were greater, in its repeatedly declared vow to reunify Zorasan. The Shah’s attempt to extend his control into Cyracana was blocked by the emergence of two warlords, Mirhussein Rasfanjani and Khosrow Shamshiri, two former commanders of the Cyracana Colonial Auxiliary Corps, who ruled their areas of influence as personal fiefdoms. To the north of both was the aspiring democratic Ashkezar Republic, led by Murad Hosein Zand. Between 1946 and 1948, fighting was limited to repeated skirmishes between the two warlord generals and sporadic clashes between the Shah and the PRRC. The skirmishes did little to slow or deter planning or preparations for a final and inevitable conflict. The Shahdom’ utilising the abandoned Etrurian colonial arsenals, possessed the largest army of the Pardarian factions but it was poorly led, with the officer corps hollowed by chronic corruption, patronage and nepotism. The PRRC’s forces, though smaller had over 20-years of fighting experience and was heavily supplied by Xiaodong through the Kharkestar Corridor.

In late 1947, eager to bolster its Pan-Zorasani credentials, the PRRC launched an incursion into Kumuso, a former province of the Shahdom, that declared independence from both it and Etruria in 1946. The invasion was met with stiff resistance and difficulties in supplying the force across the Great Steppe. The Shah immediately ordered the Imperial Pardarian Army to launch its much-awaited offensive into the PRRC, capitalising on the distraction. However, PRRC informants and agents inside the Shah’s government were made aware of the Shah’s plans and lay in wait. The imperial offensive was launched on 10 April 1948 and within weeks was encircled and destroyed by mobile cavalry units of the PRRC. Several weeks after the failure of the initial imperial offensive, its most capable and reliable commander, General Omid Deghan was killed along with 90 other officers in a Black Hand bombing of the Hotel Saffron, which was housing their headquarters in eastern Pardaran. The death of Dehgan denied the Shah his most capable officer being appointed Supreme Commander of Imperial Forces, which may well have led to an imperial victory. Over the next two-years, the PRRC would capitalise on the poor leadership in the Imperial Army, repeatedly defeating it in mass offensives and advanced north at ever greater pace.

In February 1949, the PRRC captured the imperial capital of Zahedan and the holy cities of Ardakan and Namrin. The Shah increasingly desperate fled to the port city of Bandar-e Hassan and instituted press-gangs and prison units to replace losses. The press-gangs use of violence to recruit young men and boys into the Imperial Army greatly diminished his already weak standing among his subjects and saw the steady acceptance of the PRRC and Sattarism. In October, the PRRC launched its final offensive against the Shah, capturing the city of Bandar-e Hassan as well as the Shah and Crown Prince. The two men were executed by firing squad and dragged through the streets of the city, where their bodies were beaten and damaged by baying crowds. The Shahdom unconditionally surrendered to the PRRC later that day.

From late October to November, the PRRC turned to defeat the two warlord cliques, overrunning their positions with ease with imported modern weaponry and over 500,000 soldiers. In May 1950, the PRRC launched the final offensives of the war against the Ashkezar Republic, though despite heavy resistance, the PRRC forces quickly overran the Republic’s defences, capturing the major northern port of Bandar-e Parvadeh in July. Heavy resistance by the local population coupled with growing anger at the war’s length, PRRC forces sacked the city and set it ablaze in what became known as the Burning of Bandar-e Parvadeh. The firestorm together with the violence committed by the PRRC, would leave over 6,500 people dead and the city in ruins. In August, the PRRC captured the leadership of the Republic after they fled the town of Zamharir, they were promptly executed, and the civil war was declared over.

Mahrdad Ali Sattari proclaimed in a radio broadcast the founding of the United Republic of Pardaran and the beginning of Zorasani unification. Throughout the civil war and immediately after, thousands of people were massacred or executed by the PRRC for monarchist sympathies or for supporting rival factions, this process of eliminating threats would eventually give way to the Estekham (see below) or “Normalisation”, which would begin with the persecution of suspected monarchist sympathisers and evolve to include the destruction of nomadic communities and cultures living on the Great Steppe. The Estekham would take place throughout Zorasan as unification proceeded and would only end in 1981. Over 750,000 people were killed in the Pardarian Civil War, but the victory of the Pan-Zorasanist PRRC would establish a base from which unification could be pursued and inspired. The success of Sattarism in mobilising society against a multitude of enemies would lead to the establishment of “brother cadres” in the Rahelian states, notably Khazestan. Ali Sattari and his subordinates would establish an authoritarian single-party state in Pardaran and proclaimed the state’s “sole objective and reason for existence is for the unification of the Zorasani people.” As such, the Pardarian Civil War is widely perceived as the official begging of the unification process.

Khazi Revolution

Much like its fellow Rahelian states to emerge out of the Solarian War, Khazestan fell under the rule of the most influential tribal group, the Al-Suwaydi tribe. Under the leadership of Sheyk Hussein ibn Rashid, the Al-Suwaydi through their patronage of the former Colonial Auxiliary Force of western Rahelia Etruriana enforced his assumption of power with the capture of Faidah in 1946. Under threat of violent retaliation, Sheyk Hussein guaranteed the backing of other tribal leaders when he proclaimed himself King of Khazestan.

The early effort of the Khazi monarchy to legitimise their rule faced serious pitfalls. Much like the other ruling monarchs in Rahelian Zorasan and the Shah, Hussein was perceived to be a collaborator and traitor. He spent much of his life assisting the colonial authorities, effectively becoming their intermediary with the other tribal leaders. His brother’s role as Commanding-General of the Colonial Auxiliary Force of Western Rahelia Etruriana further degraded public opinion upon his seizure of power. And like his neighbouring contemporaries, efforts at building a national identity was centralised around the monarchy and Hussein himself. As historian Said Khan noted, “the Post-Solarian Zorasani monarchs worked tirelessly to evoke identities of their nations around them and their families, to be Khazi was to be a subject of King Hussein.” Not only did this fail to cement national solidarity or unity, owing to the previously mentioned lack of legitimacy in the eyes of powerful circles, it left open space for the influence of Pardarian Pan-Zorasanism. In Khazestan’s case, these weaknesses were crippling for the monarchy. The Al-Suwaydi tribe had poor relations with its neighbours and rivals in Khazestan, while many ordinary Khazis saw the King and his family as over opulent, wealthy and corrupt, even before they assumed power in 1946. Khazestan’s historic role as the “second pillar to Pardaran within its empires” led to an innate and close socio-political and cultural relationship with its larger neighbour. The shared trials and suffering under Etruria also bridged the two states on an emotional level. The weaknesses would further fuel general discontent over a series of other grievances, over food shortages, economic failure and social injustice.

Khazestan suffered considerable damage during the Solarian War, being a major theatre of conflict between Etruria and CN forces between 1944 and 1946. The new kingdom, although possessing oil and gas fields discovered by the Etrurians in the 1920s and 1930s, failed to rebuild infrastructure adequately or evenly. Despite most cities being physically rebuilt by 1952, many homes and businesses were housed in rudimentary and poorly constructed buildings. The monarchy also focused much of its resources and revenues on rebuilding and modernising regions within the historic territory of the Al-Suwaydi tribe.

Between 1946 and 1952, the Kingdom rebuilt damaged oil facilities with Euclean assistance. However, rather than utilise the growing revenues from oil, the monarchy would utilise the capital for personal use. It is estimated that between 1946 and 1952, the Al-Suwaydi family seized up to 44% of oil revenues, what remained was then invested into tribal lands. The immense wealth and cronyism of the monarchy led to immediate economic stagnation, financial bottlenecks and the continued devastation in other parts of the country. To make matters worse, the rural poor were subject to a resurgence in a near-feudalistic relationship with their landowners, most of whom were close associates with the Al-Suwaydi tribe and its allies. Such was the severity of the landowner’s behaviour that many considered peasant life to be worse than that endured under the Etrurian colonial system.

Prior to the revolution, there were few but consequential social, economic, and political laws and reforms introduced during his reign and a number of these reforms led to public discontent which provided the circumstances for the Khazi Revolution. Particularly controversial was the replacement of several Irfanic laws with Euclean ones and the legal establishment of the Al-Suwaydi tribe over all others. The introduction of a "royal tax" on the souks shattered the already weak ties between the monarchy and the emerging urban middle class, fuelling resentment and the growth of republicanism. In 1949, Khazis who had fought in ongoing Pardarian Civil War, and those who had historic ties to the Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command during the Solarian War, united to form the Khazi Revolutionary Resistance Command. The KRRC suscribed to Sattarism and aimed to overthrow the monarchy and establish a union with Pardaran. It was led by Mustafa al-Kharadji.

Mass protests erupted in the northern city of Gharaf over the price of bread. Led primarily by women, the protests took the government by surprise, which had enjoyed relative peace since independence. The first march inspired hundreds of thousands of Gharafis to march in protest of the monarchy, resulting in the government ordering the deployment of soldiers and gendarmes to the city. Within days the Gharaf protests spread to other cities in the north, notably the vital port of Bashaer.

On 1 August, protests in the port-city of Bashaer led to the shooting and killing of Pešvar Ashavazdah al-Safwani. The killing of an Irfanic cleric by the Royal Gendarmerie inflicted serious damage to relations between the monarchy and the Irfanic establishment, while the news of the killing provoked escalating riots and protests in the north and now the south of the country. In response, the government forces resorted to unrestrained violence, killing over 300 protesters in the first week of August The monarchy, unable to recognise the link between the killing of protesters and their escalating action against the state further fuelled widening opposition to the monarchy and increased the death toll. This unbreakable cycle led to the King declaring martial law on August 19th.

On August 31st, the Khazi Revolutionary Resistance Command emerged from hiding and seized the western city of Abbassiyah from monarchist forces. The KRRC’s call for its members in the Royal Armed Forces to rise up against the King was answered by several cells. Mutinies and clashes between various military units destabilised the government’s response and served as a catalyst for the King’s paranoid-fuelled violent crackdown.

Between September and early November, the country would be wracked by rioting and repeating cycles of government forces killing protesters and facing renewed ever more ferocious protests, strikes and acts of civil disobedience. The same period, from Abassiyah, the KRRC organised its cells in other parts of the country to conduct sabotage against government property. On the 8th October, a large explosion disabled the primary oil refining facility in Bashaer, inflicting crippling losses on the Khazi-Weranic Oil Company.

On the 3 November, Mustafa al-Kharadji, the leader of the KRRC declared the group to be the “vanguard of the revolution”, calling upon Khazis to join with the KRRC to “finally overthrowing the despot King and his clan of criminals.” Across the country, KRRC cells began to distribute weapons to protesters and defecting soldiers, leading to pitched battles between protesters and the Royal Armed Forces. The emergence of armed resistance forced the disintegration of the King’s military as thousands of soldiers refused to shoot civilians. Despite the loyalty of the Royal Guard and highly paid members of the gendarmerie, the revolution rolled on toward capturing Faidah.

On 7 November, King Hassan ibn Rashid and most of his family fled the capital for their ancestral hometown of Hejjnah. Within an hour of the family’s flight, protesters breached the gates of the Al-Suwaydi Palace in Faidah, looting its rooms and setting it ablaze. The next day, a KRRC cell in Hejjnah intercepted the King’s convoy as it approached the Al-Suwaydi tribal capital, capturing the King, his wife and four sons. They were taken to small farmhouse and given a mock trial and executed by firing squad.

The death of the entire senior royal family denied the remaining loyalists a reason to resist and resistance to the revolution began to fall apart. On 9 November, Mustafa Al-Kharadji proclaimed the formation of a Provisional Revolutionary Government, while thousands of protesters were organised in Revolutionary Protection Units by the KRRC and charged with pursuing and destroying any royalist holdouts in society. Fearing reprisal, many officers of the Royal Armed Forces pledged their support for the new provisional government, condemning or denouncing many of their comrades who proved too slow at making the pledge. Throughout November, an estimated 19,000 people would be killed or disappeared by the Revolutionary Protection Units and a further 25,000 predominately members of the Suwaydi tribe fled the country for Riyadha and Irvadistan.

Rahelian-Kexri conflcit

The seizure of territory in the former Etrurian colony of Ninavina, by the Free Kexri League with support from Rahelians within the territory proved to be a unique development in relation to the ethno-nationalism of its neighbouring regions. The establishment of the Free Kexri Republic in 1946 belied a highly inclusive and aspiring democratic system. However, the ruling Free Kexri League from its conception, was dogged by internal factionalism and vicious power-struggles between prominent Kexri figures. The two prominent factions was the left-wing Kexri nationalist, Kexri People’s Socialist Front and the Kexri-Rahelian led Free People’s Democratic Party.

The free and open society established upon independence provided space for Pan-Zorasanist elements to coalesce into the Ninevah Revolutionary Movement. By 1949, the NRM had seen a dramatic rise in popularity among the Rahelians living around Lake Zindarud, where they were subject to the regular propaganda broadcasts from Pardaran. Fearing the NRM may jeopardise the independence of the Kexri Republic, the KPSF began to agitate against the FPDP government. In November 1949, the NRM officially declared its intention to lead the Kexri Republic into unifying with any Pan-Zorasanist state yet to merge, to which the KPSF declared the party a security threat. Using the government’s refusal to shut down the NRM, Kexri militia groups linked to the KPSF seized control in a coup on 22 November 1949.

The KPSF government under Ciwan Haco declared a state of emergency and banned the NRM on 4 December. The ban sparked protests by the Rahelians of Lake Zindarud, which were violently put down by Kexri militia. On 10 December, Haco expanded the state of emergency to shut down all Rahelian-centric political parties and those that “would promote a space for such parties”, essentially turning the Republic into a single-party state.

The KPSF government beginning in 1950, implemented a policy of Kexrisation. Forcing the exclusive use of Kermanji on the population. This policy also instituted harsh crackdowns on the Republic’s Yazidi minority, specifically its religious practices as the KPSF hoped to establish institutionalised secularism, this also served to further ferment unrest among the Rahelian population. Further protests were met with heavy-handed police and militia responses, pushing the disbanded NRM into establishing contact with the Padarian Revolutionary Resistance Command for assistance. The PRRC, which was close to defeating it rivals in the Padarian Civil War responded with shipments of arms and trainers across Lake Zindarud. The PRRC saw the Kexri situation both as an opportunity to prove its Pan-Zorasanist credentials and to combat what it saw, as rising socialist Dezevauni influence.

On February 3, armed Rahelians, led by Pardarian officers, seized control of the lake-side town of Qesirdîb. From there, Rahelian armed militia began to infiltrate the rest of the Kexri Republic, while the town became the primary link between the resistance and Pardaran. A Kexri armed attack on February 20, failed to dislodge the militias, who promptly formed the Ninevahi Revolutionary Resistance Command on February 23. On March 10, NRRC units captured in the town of Sêmalka, opening a route to the Yazidis residing on the eastern shores of Lake Mahaldar. Fearing a coordinated armed uprising, the KSPF government ordered a full-scale attack on the Rahelian western region, with the aim of ejecting any NRRC influence from the major city of Ad-Daydh. The widespread distribution of weapons smuggled across Lake Zindarud, coupled with routes across southern Khazestan enabled NRRC groups to resist the Kexri offensive, sparking the Rahelian-Kexri conflict.

Throughout 1950 and 1951, the Kexri forces bought a bitter Rahelian insurgency in the central and western regions of the country. Lacking any certifiable navy, the Kexri Republic struggled to interdict the supply of weapons and volunteers from Pardaran to the insurgency across Lake Zindarud. On the 17 April 1951, a Pardarian air attack on the Kexri lake-side town of Hajaka destroyed ten patrol boats. The loss of these boats enabled a brief period for Pardaran to transport several thousand soldiers across Lake Zindarud unhindered. Boosted by the 2,800 Pardarian soldiers, the NRRC captured the city of Ad-Daydh. The loss destabilised Kexri morale, who in turn became ever more reliant on violent reprisals against Rahelian civilians as a means of maintaining control. These reprisals often massacres of entire Rahelian communities resulted in the retraction of support from the Rahelian monarchies in Riyadha and Irvadistan. The Khazi monarchy, hoping to beat back criticism and popular opposition, sealed its border with the Kexri Republic. With no alternatives, the left-wing KSPF government turned to Dezevau for support, which only fuelled Pardarian fears of a Dezevauni intervention against Pan-Zorasanism. The Pardarians under Mahrdad Ali Sattari stepped up their support for the NRRC, dispatching a further 2,000 troops across Lake Zindarud and instituting a lake wide blockade of the Kexri Republic through its maritime militia which harassed Kexri fishing boats and freighters.

1952 would be the pivotal year in the conflict, as the Khazi monarchy was overthrown by the KRRC, its new leader, Mustafa al-Kharadji declared his intention to end the “Red Kexri menace.” On December 3, only days after the overthrow of the monarchy, the KRRC sent 35,000 soldiers into the Kexri Republic. Backed by 10,000 Pardarian troops, together with the NRRC, the Kexri forces were overwhelmed and collapsed under the weight of the Pan-Zorasanist offensive. On December 25, the Kexri capital of Naqad fell. Ciwan Haco and many of the KSPF leadership fled to Dezevau or Mabifia days after and opted to wage a Kexri resistance from abroad, which would extend the Rahelian-Kexri conflict for another twenty years. The conflict in the Kexri Republic from 1950 until 1952, left over 90,000 dead and displaced over 300,000 people.

Following the fall of the Kexri Republic, the NRRC proclaimed a Provisional Revolutionary Government and supplanted the Kexri-dominated state with one comprised of entirely of Rahelians and Yazidis. With Pan-Zorasanists in control of Pardaran, Khazestan and Ninevah, the stage was set for the first major success of Zorasani unification.