Intharatcha

| Intharatcha the Great 拉賈拉賈 อินทราชาใหญ่ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King of Khaunban Lord of the Ten Directions Great King of the East | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Reign | 1 April 1647 - 11 July 1673 | ||||||||

| Coronation | 11 July 1647 at Khaunban 12 February 1661 at Rongzhuo | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Mahathammarachathirat | ||||||||

| Successor | Borommarachathirat | ||||||||

| Suzerain of Lanhok | |||||||||

| Reign | 9 March 1652 - 11 July 1673 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Office created | ||||||||

| Successor | Borommarachathirat | ||||||||

| King | Nodthakorn II (1652-1668) Kirakorn (1652-1681) | ||||||||

| Suzerain of Chensae | |||||||||

| Reign | 16 July 1652 - 11 July 1673 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Office created | ||||||||

| Successor | Borommarachathirat | ||||||||

| King | Sukonthor (1652-1652) Chettha (1652-1654) Ang Chan I (1654-1670) Satha I (1670-1672) Chey Chettha I (1672-1673) | ||||||||

| Suzerain of Myiang | |||||||||

| Reign | 19 September 1652 - 11 July 1673 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Office created | ||||||||

| Successor | Borommarachathirat | ||||||||

| Suzerain of Muendap | |||||||||

| Reign | 3 February 1653 - 11 July 1673 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Office created | ||||||||

| Successor | Borommarachathirat | ||||||||

| King | Kathawut (1653-1666) Pralop II (1666-1668) Nirund (1668-1673) | ||||||||

| Suzerain of Vihkenadebau | |||||||||

| Reign | 8 July 1653 - 11 July 1673 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Office created | ||||||||

| Successor | Borommarachathirat | ||||||||

| Prince | Saw E (1653-1671) Khon Law (1671-1673) | ||||||||

| Suzerain of Sipmueang | |||||||||

| Reign | 21 May 1655 - 11 July 1673 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Office created | ||||||||

| Successor | Borommarachathirat | ||||||||

| King | Pichai (1653-1659) Thongchai (1659-1673) | ||||||||

| Suzerain of Namoset | |||||||||

| Reign | 18 August 1655 - 11 July 1673 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Office created | ||||||||

| Successor | Borommarachathirat | ||||||||

| King | Phrom-Borirak (1655-1673) | ||||||||

| Suzerain of Nainan | |||||||||

| Reign | 28 April 1658 - 11 July 1673 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Office created | ||||||||

| Successor | Borommarachathirat | ||||||||

| King | Thảo Thánh Tông (1658-1658) Thảo Nhân Tông (1658-1663) Thảo Cao Tông (1663-1667) Thảo Chiêu Hoàng (1667-1673) | ||||||||

| Suzerain of the Great Jiao | |||||||||

| Reign | 17 December 1660 - 11 July 1673 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Office created | ||||||||

| Successor | Borommarachathirat | ||||||||

| Emperor | Taizong Emperor (1660-1667) Taichu Emperor (1669-1671) | ||||||||

| Born | Supsampantuwongse Chaowas Nai-Thim 10 March 1624 Khaunban | ||||||||

| Died | 22 November 1673 (aged 49) Juancheng | ||||||||

| Burial | |||||||||

| Consort | Neungluthai | ||||||||

| Consorts | Thao-Ap Thảo Liên Hoa Tanaka Sai Liu Nüying (Over 50 more, see Consorts) | ||||||||

| Issue Detail | Norrapan Borommarachathirat Chariya (Over 90 more, see Issue) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynasty | Khaunban | ||||||||

| Father | Mahathammarachathirat | ||||||||

| Mother | Manya-Phathon | ||||||||

| Religion | Zohism | ||||||||

Intharatcha the Great (Kasi: 拉賈拉賈 อินทราชาใหญ่, RKGS: Inotrachayai), was the 6th monarch of Khaunban and the 1st Khaunban Emperor, from 1647 to 1673. He was a highly intelligent, ruthless, and militaristic monarch whose 26-year reign saw the rapid creation of one of the largest empires in Coius. At his empire's height in 1665, his rule stretched from Rongzhuo in the west to Sungai Baru in the east, and he received tribute from over 20 nations.

Intharatcha spent most of his ruling years on an unprecedented military campaign throughout Southeast Coius, and by the age of 35 he had subjugated most of it. Until his expedition into Shangea he remained undefeated in battle, and continued to win the vast majority of his battles. He is regarded as one of the most successful military commanders in history, known for his innovative strategies and Grand Army. While known less for it than his military achievements, his political, cultural, and religious legacy has made him one of the most celebrated monarchs of Kuthina, though he remains controversial in Shangea and elsewhere in Southeast Coius.

Born Supsampantuwongse Chaowas Nai-Thim, a prince of Khaunban, a modest city-state under the suzerainty of the Kingdom of Sippom, he came to the throne in 1647 after his father, Mahathammarachathirat, was murdered by Kraisingha of Sippom. In response he led a successful revolt against Sippomese rule which placed him in control of the Lueng river valley. He undertook the creation of his Grand Army and used it to great effect over the next 11 years conquering and subjugating much of Southeast Coius, including the Kingdoms of Chensae, Lanhok, Myiang, and Nainan. Their integration into his empire remained loose, and he would spend much of his reign dealing with revolts and internal strife.

The collapse of the Jiao dynasty in 1659 presented an opportunity to Intharatcha, and in 1660 he invaded Shangea and captured Rongzhuo. The Jiao princes vacillated between opposing him and requesting his aid, which, along with rebellions back home, greatly hampered his ability to commit to the Shangea campaign. In 1667 Rongzhuo was taken during his absence, and in 1668 his reputation suffered greatly after a devastating loss at the Battle of Yuan'an. He spent the remainder of his reign dealing with revolts in his unstable empire, which would continue to plague his successor and help cause the rapid decline of his short-lived empire.

Intharatcha built an empire on a scale not seen in Southeast Coius before, one which in his mind rivalled and outshone that of the Svai Empire, and the concurrent Shangean and Senrian empires, which he sought to subjugate. Like previous Kasi monarchs he was a zealous Zohist and he built, converted, and patronised over a hundred temples. While his empire did not last, his unification of the Kasi Kingdoms of the Upper and Lower Lueng endured, as did the Kasi suzerainty of the Svai and Nyaram kingdoms. He remodelled the concept of Kasi kingship from that of a paternal father and personal ruler, to that of a divine autocratic monarch, a system which would endure until the Khanompang Revolution and institution of constitutional monarchy in 1961.

Name

While he was born Supsampantuwongse Chaowas Nai-Thim, he is most commonly known by his regnal name, Intharatcha. Intharatcha is a compound name, of Intha and Ratcha. Intha derives from proto-Pardarian *Indrah, which is became the name for the deity Indra. The worship of Indra was once widespread across Zorasan, Satria, and the Great Steppe, but he is more commonly known as as the Zohist deity Yìnlā. His name is synonymous with the symbolism of a divine chariot. Ratcha derives from the Parbhan rājan (राजन्), meaning king, which was translated into Shangean with the meaning of deity or divine, as Lājiǎ (拉賈). Compounded together Intharatcha translates to 'Chariot of the Gods'.

His ceremonial name, which was used on decrees and is present on statues dedicated to him and on his tomb is:

Intharatcha Thirakkhongchakho Hokkhongmueang Chaohaengthongfalaelok Lukchailangkhaen Phrachaokhonglok

印拉拉賈 情人姐光 矛城 主方天世 儿子复仇 上主河世

อินทราชา ที่รักของชาโค หอกของเมือง จ้าวแห่งท้องฟ้าและโลก ลูกชายล้างแค้น พระชายาโขงโลก

This translates to:

Chariot of the Gods, Beloved of Shako, Spear of the City, Master of Sky and Earth, the Avenging Son, the Divine King of the World

Early life

Born Prince Supsampantuwongse in 1624, he was the son of Mahathammarachathirat of Khaunban and Chantara, a junior consort. His mother was from Lue nobility, but did not rank high among Mahathammarachathirat's consorts. Intharatcha was the eighth son of Mahathammarachathirat, and was not expected to attain the throne. His elder brothers Prince Nitithorn and Prince Thinnakorn were considered the likeliest heirs.

As such Intharatcha's education was largely oriented towards military matters. It was expected that he would either serve one of his brothers, or find service elsewhere in Sippom, the suzerain of Khaunban. Khaunban at this time was a minor city-state, although it had a history of rebellion and struggle against Sippomese rule.

From the age of 6 he was fostered in the Lue state of Phatang, and after its conquest by the Kingdom of Myiang at age 8 would spend his time in the court of Yarzar Zin. He would establish a life-long friendship with its crown prince, Saw E, who would later become Myiang's king, and one of Intharatcha's most trusted subjects. He soon became fluent in the Chanwan language and at the Battle of Zigon at age 17 he won a decisive victory for his foster father, being honoured with a marriage to Zin's daughter, and Saw E's half sister, Neungluthai (née Nila Tun).

Rise to power

The reigning king of Sippom, Kraisingha, viewed Mahathammarachathirat, who had been steadily expanding Khaunban's control over neighbouring towns and creating a web of allies, as a grave threat. In late 1646 He ordered Mahathammarachathirat to attend him at the capital in preparation for a new campaign against the Lue states to the north. Mahathammarachathirat acceeded to his request, but entered talks with the Lue leaders to prepare a trap for Kraisingha. When he reached the capital, however, he was murdered in the streets, while Prince Nitithorn was taken hostage.

In Khaunban Prince Thinnakorn immediately seized the throne. Kraisingha released Nitithorn, and sent a decree to Thinnakorn requesting his abdication in favour of Nitithorn. Nitithorn was later poisoned, likely on Thinnakorn's orders, and Kraisingha accepted his offer of submission and recognised him as the ruler of Khaunban. Upon hearing of his father's death at age 23 Intharatcha returned home to Khaunban with a small army. He challenged his brother for the throne, and after a fierce elephant duel during the Battle of Nampouy, killed Thinnakorn. With the support of the nobility and his other brothers Intharatcha took the throne.

Revolt against Sippom

Upon taking the throne Intharatcha declared that he would seek justice for his father's death, and as soon as he could rallied his forces. Several other client kings of Sippom also took the opportunity to break away, and the Lue began raiding Sippom's northern town's. Unable to come to terms with the other breakaway kings, who refused to acknowledge his leadership, he planned to march alone on Sippom as soon as possible. Kraisingha had alienated not only the kings of his client states, but also the citizens of Sippom, and was regarded as a tyrant. Upon hearing of Intharatcha's rebellion, Kriang Sak, one of Kraisingha's generals and son-in-law, led a palace coup and installed himself as Sippom's king.

Kriang Sak met Intharatcha at the Battle of Vangkhi, where his army was defeated, but he managed to escape back to Sippom. He was assassinated, and Kraisingha was reinstalled as Sippom's king. A second army was defeated at the town of Phokay, which surrendered, providing Intharatcha a clear path to the capital. His arrival precipitated a riot in which Kraisingha and many officials were murdered, and in the confusion one of the gates was opened. The city underwent two days of mayhem, and is not clear whether the city was sacked on Intharatcha's orders, or as a result of the chaos ensuing from the invasion. Order was eventually restored, and Intharatcha severely punished those who had killed Kraisingha for harming, in his view, an inviolable and sacred monarch.

Nai-Thim, his brother, was installed as Sippom's king, a position he would hold until his death in 1578. He would serve as its governor while Intharatcha was absent, and remained loyal to Intharatcha and Borommarachathirat, which allowed him to be succeeded by his son Intradit.

While Khaunban remained his capital, Intharatcha would spend more time in Sippom. Those in favour in his court took up residence in its palace, while those outside his grace would find themselves relegated to Khaunban or the provinces. The institutions which administrated his empire would also be located here. Finally, its significance to him was shown by his decision to be buried in its temple, which he heaped lavish wealth upon.

Creation of the Khaunban Empire

Upper Lueng river valley (1650)

Subjugation of the Kyin and Lue (1651)

Lanhok (1652)

Chensae (1652)

Myiang (1652)

Expansion of the Khaunban Empire

Muendap (1653)

Vihkenadebau (1653)

Taraotung (1653)

Tchin Kingdom (1654)

Sipmueang (1655)

Namoset (1655)

Akhir States (1657)

Nainan (1658)

Maintaining the Empire

Administrative practices

Revolts and rebellions

Economy

Chakela decree (1655)

Invasion of Shangea

Shangean ambitions

1660 Invasion

The Jiao fixture on their troubles in the west meant that their eastern border with the belligirent Khaunban Empire had become effectively defenceless. Garrisons and commanders still loyal had been pilfered to prepare for expeditions to retake Baiqiao. A letter from Intharatcha to the Taizong Emperor also further lowered defences, as he professed his loyalty as a subject and offered his aid, which was declined. Reports of attacks on Zhaili were dismissed as being the work of bandits, and the surrender of Juancheng by its commander Zou Qiuyue went unnoticed in the Imperial Court, which had greatly suffered from many officials being left behind in the flight from Baiqiao.

Intharatcha had designs on expanding into Shangea as early as 1655, when he wrote to the Senrian Emperor Ninpei to encourage a joint invasion as a retaliation for the Soukou War. While Ninpei dismissed the notion, as he was organizing an effort to restore imperial power within Senria, Intharatcha was assured that the Senrians would take no action to hinder his plans. The implosion of the Jiao dynasty after the Red Orchids took Baiqiao in 1659 provided him the perfect opportunity to launch and invasion disguised as rendering aid to an ailing dynasty.

By the time the Imperial Court was aware of Intharatcha's intentions, the Grand Army was only several days away from Rongzhou. The Taizong Emperor refused to abandon the city, believing that it would doom the Jiao's efforts to reconquer the west, and that Intharatcha was an ally. Several princes, led by Liu Zihao, Prince of Liang disagreed with this policy, and fled the city. In the confusion many soldiers began looting and burning parts of the city, and several notable commanders such as Tao Jinjing and Dong Fenfang were killed attempting to end the riots. The Imperial Court and the emperor fled the city, and were found on a nearby hill by Intharatcha's advance guard, who took them to him.

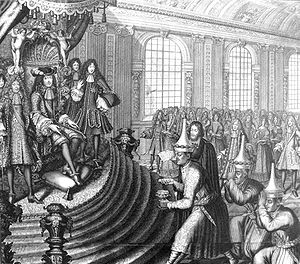

Intharatcha and his army entered the largely abandoned city with no resistance. Intharatcha declared his intention to restore the Jiao, and was invested by the Taizong Emperor as the 'Great King of the East' (偉大东王 Wěidà dōng wáng). Liu Meilin, Prince of Chen was the only prince to accept Intharatcha's coup, with the Prince of Liang declaring himself the Taichu Emperor, with his base in Zhoujia. The Eastern Jiao became firmly split, although the lines between the Taizong and Taichu factions would become blurred, particularly after 1667.

Second coronation

Conquest of Yingtan (1662)

Jiao princes and domestic troubles

Fall of Rongzhuo (1667)

Intharatcha's return eastwards to deal with domestic rebellions did not go unnoticed by Toki Sinzou or the Jiao princes. The Prince of Wu launched several attacks, aiming to take Wudan, but was ultimately unsuccessful due to the intervention by the Prince of Chen and Kriang Krai. This, and raids by the Prince of Ji, left the Prince of Chen and Kriang Krai preoccupied, and Hongyan open. Sinzou despatched a force under Ogawa Yorihiko to Wudan in a feint attack, while he took the bulk of his army to Hongyan. Hongyan's governor, Cui Changpu, held a grudge against the Prince of Chen, and defected, surrendering the city.

The path to Rongzhuo became open, and Sinzou decided upon taking it before Wudan. Capturing the Taizong Emperor would give him greater legitimacy, and possessing Rongzhou and Baiqiao would mean possession of nearly all the Jiao institutions and officials. An army under Mizuno Youhiko was sent to tie down Kriang Krai, but the Kasi general was able to return to Rongzhou. The Prince of Chen remained near Wudan with orders to march to Rongzhou in the event of a siege, which due to threats from the Prince of Wu he was unable to comply with.

Fearing an elongated siege would cause the Jiao garrison to turn on him, Kriang Krai elected to meet Sinzou in battle, where at the Battle of Rongzhuo he was beaten and forced to fall back. Sinzou put the city to siege for three months, after which, as Kriang had predicted, the Jiao garrison mutinied and defected. Kriang narrowly evaded capture by jumping into the Liaojing river, while the Taizong Emperor was captured by defecting troops and delivered to Toki Sinzou.

The defection did not go smoothly, with Kriang's soldiers and elements of the garrison refusing to mutiny. This resulted in a day of sacking and looting, contrary to Sinzou's wishes, and the Rongzhuo massacre, in which over 10,000 of Kriang's soldiers, as well as thousands of Shangean 'collaborators' were executed, despite Sinzou's general pardon and desire to take hostages. The reason for the massacre is contentious, with Shangean historians claiming it had been orchestrated by Sinzou and undertaken by Senrian mercenaries, while Kuthine and Northern historians argue that it was largely undertaken by the defecting Jiao troops against official policy.

Battle of Yuan'an (1668)

The Battle of Yuan'an was one of the most decisive and bloodiest battles of the Toki conquest of Shangea. After Toki Sinzou had taken advantage of Intharatcha's absence to capture Rongzhou, the Khaunban king intended to regain the initiative by defeating Sinzou in a pitched battle, and thus gain control over the beleagured Jiao forces. Intharatcha had at his disposal 150,000 of his Grand Army, with Natthapong, Tharathorn, and Vĩnh Nhật Tấn commanding, along with 30,000 Jiao soldiers under the Prince of Chen. An additional 80,000 under the Prince of Teng had been promised to support him. He faced a force of 60,000 led by Chen Haiping, with Zhong Jianjun leading a relief army of 35,000, and Toki Sinzou besieging nearby Zhoujia with over 100,000 soldiers.

Intharatcha had despatched Tharathorn with 60,000 men to take Batang fortress, to place pressure on Toki Sinzou and force him to relieve the siege of Zhoujia. He approached Chen's army on the 5th May, but neither side engaged the other until the 12th, with both waiting in vain for reinforcements. Unbeknownst to Intharatcha, Zhong Jianjun's army had ambushed Tharathorn's army at Batang and defeated it, killing Tharatorn in the process, while the Prince of Teng had elected to march instead to Zhoujia, before retreating to his stronghold in Yinbao.

Although Intharatcha had the advantage in both quantity and quality of troops, he was indecisive over whether to give battle and was taken by surprise by Chen's attack. Initially he had the upper hand, inflicting heavy losses on Chen's forces. His decision to place the Prince of Chen on his right flank, protecting the road to his camp, proved a fatal mistake, as Chen Haiping was able to break the dispirited Jiao forces with a cavalry charge and outflank Intharatcha while pushing into his baggage train. Intharatcha's attempts to start an orderly retreat quickly turned into a rout. In the chaos Natthapong was killed, and Intharatcha narrowly escaped capture. Vĩnh Nhật Tấn was able to lead 30,000 survivors southwards, while Intharatcha led the remaining forces back to the safety of Juancheng.

The battle was a turning point for the burgeoning Toki dynasty. The invincibility of Intharatcha and his Grand Army, already shaken by the capture of Rongzhou in 1667, had been shattered. His Grand Army lost two experienced commanders, most of its elephant corps and cannon, and a great deal of veterans, losses which Intharatcha was unable to replace. It also sowed further seeds of distrust between Intharatcha and the Jiao princes, as the former blamed the princes of Chen and Teng for the defeat. Most significantly, the battle secured Toki Sinzou's siege of Zhoujia, which would fall several months later.

The defeat had a great psychological effect on Intaratcha, who before it had never suffered such a setback. His ministers noted that he no longer seemed enthusiastic about his campaign in Shangea. According to the the Mengrai's Yai Intaratcha he said of it:

One defeat is worth a thousand victories

Khwāmph̀āy phæ̂h̄nụ̀ng khrậngmī kh̀āmākkẁā h̄nụ̀ngphạn chạychna

ความพ่ายแพ้หนึ่งครั้งมีค่ามากกว่าหนึ่งพันชัยชนะ

Later years

The Battle of Yuan'an delivered a crushing blow to Intharatcha's ambitions in Shangea, but it did not end his campaign altogether. Various rebellions across his empire forced him to personally withdraw from Shangea for two years, leaving his generals to execute a defensive policy. They were aided in this regard by the Toki's focus upon the remaining Jiao dynasty cities to the south, and on the remaining Red Orchids in the west. In the meantime Intharatcha put down revolts by the Taraotung cities and in Nainan. By 1670 he had stabilised his domains, and had revitalised his Grand Army with new conscripts and officers.

The situation he faced in 1670 was starkly different to that of 1660. Instead of a highly fractured Shangea, he now faced an ascendant Toki with, crucially, no support from the remaining Jiao forces. Liu Zihao, Prince of Liang, the self-proclaimed 'Taichu Emperor' of the Southern Jiao had been assassinated a year prior, leading his relative Liu Yuanjun, Prince of Wu to declare himself the 'Taian Emepror'. Intharatcha had been able to form a tense alliance with Liu Zihao, promising secretly to force the Taizong Emperor to abdicate in his favour. In contrast he loathed the Prince of Wu who had consistently led an anti-Khaunban faction within the Southern Jiao. In response he declared a new Kun dynasty, and backdated its formation to his second coronation in Rongzhuo in 1661.

It was not the circumstances he had intended to declare his new dynasty in. His initial plan had been to conquer Shangea under the guise of restoring the Jiao, before having the Taizong Emperor abdicate in his favour and thus creating the image of a continued Jiao dynasty. Without Rongzhuo he no longer had the legitimacy of holding one of Shangea's capitals, and by this point he had lost all support from the Jiao princes. Even the Prince of Chen, his long-time ally, sided with the Prince of Wu and would fight against him.

Lacking the strength to engage both the Toki and the Jiao simultaneously, Intharatcha decided upon a southern strategy. While the Toki were occupied in the west, Intharatcha planned to sweep through the Southern Jiao, as well as the Toki's new holdings in the area, and push through to Shenkong. From there he could take Hongyan and cut off the Toki route to Rongzhuo. After retaking the capital he would have regained the initiative, and could continue his conquest of Shangea.

His strategy suffered from a fatal misunderstanding of the Jiao strength. Intharatcha had incorrectly assumed that they would meet him in battle, allowing him to win one or several decisive victories and shatter their morale. Instead they opted to withdraw to walled cities, forcing Intharatcha to divide his forces and become bogged down in a war of attrition. His attempts to scour the countryside to force them into battle also failed. He eventually took a number of cities, but by 1672 his advance had completely stalled and the Toki forces had returned from the west. Fearing that Toki Sinzou would make a push for Juancheng and cut his supply lines Intharatcha made the decision to withdraw.

He would spend the last year of his life attempting to draw out Sinzou. Sinzou was reluctant to do battle with Intharatcha, knowing that it had been the weakness of the Jiao forces which had allowed victory in Yuan'an, and having learned from the Jiao's stubborn defence that Intharatcha was unaccustomed to a slow war of attrition. Intharatcha's empire had been built upon rapid assault, achieving decisive victories over his enemies which forced them to the negotiating table. Shangea had become a quagmire, a vast country of impregnable walled cities and lacking a singular central authority able to submit to him. After Yuan'an, Intharatcha had come to refer to the conflict as his "Shangean Ulcer." He withdrew to Juancheng, intending to reassess his strategy and gather his Grand Army for another expedition against the Toki.

Administration

Fragile empire

Foreign policy

For Intharatcha policy towards Southeast Coius was less 'foreign' and more 'domestic'. He considered himself to be the rightful suzerain of the area, and so treated the rulers of all the nations therein as he treated his own subordinates. This was his policy even before he began his conquests, which earned him the enmity of his neighbouring states and necessitated a militaristic approach to enforcing it. He adopted the Shangean model of tribute, although he took an active interest in the domestic affairs of his subject states, often replacing disloyal kings and executing officials who urged resistance to his suzerainty. He would often reside in the main palaces of his subject monarchs, relegating them to lesser palaces or even humiliating them by sending them out to their provinces to act as governors.

His policy towards the Jiao dynasty was largely pragmatic. It is clear that from 1655, and perhaps even earlier, he intended to invade Shangea and likely usher in his own dynasty, but until 1660 he played the part of a loyal tributary. He sent lavish gifts after each of his conquests, in return the Jiao would recognise his new sovereignty over said areas and thus grant him further legitimacy. After the fall of Baiqiao to Red Orchid rebels in 1659, he invaded in 1660 and captured Rongzhuo that same year. After this the Jiao became both allies and enemies, and as both they ended up frequently hindering his plans in Shangea. This infighting allowed for the rise of the Toki dynasty, who would continue their unification of Shangea after his death in 1673, and would later sack Khaunban in 1682.

Relations between Senria and the Khaunban Empire were typically warm, if of a lesser nature due to the distance and divergent interests of the two nations. Senria was in the midst of the bloodiest part of the Tigoku period and so their court had little interest outside of their isles, as shown by their refusal of Intharatcha's offer in 1655 to jointly invade the Jiao. Intharatcha's main policy towards Senria was ensuring that they remain unresponsive to his affairs, and he benefited from their crises through the hiring of many tankenhei. While he had tentative plans to invade Senria or demand their subjugation, this was always envisaged to happen after a successful invasion of Shangea, which after 1668 became highly unlikely and so was largely forgotten.

The rise of Intharatcha's empire coincided with the height of the Agudan Empire. The two states had a tense relationship, made worse by Intharatcha's subjugation of the Akhir states, cities which had previously been under the protection and suzerainty of the Agudans. Intharatcha was also a fanatical Zohist, and his liquidation and conversion of Badi temples and shrines further strained relations. Despite this both empires had shared interests in combating the various polities of the Great Steppe, including the Togoti Khaganate, and this along with complications elsewhere meant that they never came to blows. The flow of trade, skilled artisans, as well as mercenaries between the states, particularly cannoneers and musketmen from Aguda, and elephantry from Khaunban, also helped keep the peace.

Satria was largely under Togoti control by the mid 17th century, and so Intharatcha's primary concern in this area was with the Togoti, an empire which he considered his main rival and threat and yet one which he never came to blows with. His correspondence with Aryabhata Pandya, a prominent Togoti official and Satrian prince, reveals that after dealing with Shangea, Intharatcha intended to 'liberate' Satria from Togoti rule. This is further supported by his patronage of, and dealings with, anti-Togoti Gukdongs in the Ansan Empire. After 1665 and the Gurkhan's death the Togoti Khaganate fell into a civil war and began losing control over Satria, and by 1668 dialogue between Aryabhata and Intharatcha had ended along with any talk or plans to invade Satria.

Intharatcha proved keen to open up relations with Euclean nations, particularly Gaullica. Gervasius Jacquet, a Gaullican Catholic priest had become a favourite of Intharatcha's soon after his arrival in 1658, and taught the king much about Euclea. Jacquet was never able to convey his own ideas about Gaullica's importance to the king, who also listened to Estmerish and Povelian courtiers, but he was able to convince him to send an embassy to Gaullica in 1662. Intharatcha wrote a personal letter to Francois II, and gave him lavish gifts, exceptionally including a white elephant. The Khaunban ambassadors to Gaullica worked hard to ensure the Gaullican reciprocal gift would be lesser in value, thus establishing Gaullica in the traditional manner as a client state of the Khaunban, unbeknownst to the Gaullicans. Euclean influence in Intharatcha's itinerant court would gradually decrease as his war in Shangea and fracturing empire outweighed foreign policy towards a very far off land.

The New World was a place that fascinated Intharatcha, and he requested his ambassadors to Gaullica acquire for him as many maps as possible. From his writings it is clear that the concept of terra nullius confused him, and he assumed that the Eucleans were attempting to mask failures to conquer extant and great native empires. His attempts to purchase land in the New World never came to fruition, and it is clear that he considered the land as military outposts for future invasions instead of as colonies for settling or for profitable enterprises. He made tentative plans to invade the Asterias from the west, after conquering Shangea and Senria, and subjugating Satria, but paid little attention to the idea or the Asterias after 1667.

Religious policy

Unlike most Kasi kings, the rulers of Khaunban held a preference for Zohism over that of Badi or the folk religion still practiced by many of their subjects. Intharatcha was a particularly devout Zohist of the school of Busothaq, which emphasised spirituality and mysticism. He envisioned himself as a living Chakela, and believed that his conquest of Southern Coius would bring him to an enlightened state of near-divinity as a conscious Chakela. Further to this end he patronised many Zohist temples, and constructed over a hundred during his reign. In the capitals of each state he conquered he constructed vast temples, sometimes demolishing entire areas for them, some of which still survive to this day, albeit often as Badi temples, or museums.

While Intharatcha largely continued the tolerant policies of his predecessors, it has been noted that he often took a harsh stance on Badi and its practitioners. He regarded it as a 'foreign atheistic religion', and a threat to his political position as a divine monarch. Major Badi temples suffered from liquidation or conversion after his conquests, rarely gave permission for the building or restoration of Badi temples, and Badi clergy suffered spontaneous persecution.

Intharatcha took a great interest in Sotirianity, particularly Solarian Catholicism, which was introduced to his court by Gaullican and Povelian priests and merchants. The Catholic Priest Gervasius Jacquet tutored the king on the religion, hoping to gain a convert, but was disappointed in these efforts. Intharatcha saw similarities between his own faith, Zohism, and that of the Eucleans, Sotirianity, and began to believe that Soucius' disciples had spread their underground communities all the way to Adunis. He further identified Jesus Sotiras as an emanation of Yi, as the brother of the semi-divine legendary Shangean emperor Kela Keshi who introduced Zohism to Southern Coius, as having much the same role but for Northern Coius and Euclea.

His embassy to Pope Urban XII in 1662, which followed a previous meeting with Francois II in Gaullica, was largely a failure for both sides. Urban XII invited Intharatcha to convert to Sotirianity, while Intharatcha had personally prepared a lengthy treatise to persuade the Pope that Sotirianity was a misunderstood form of Zohism. He also gifted Urban gilded copies of four of Zohism's higest scriptures, the Chingtze, Te Pipan, Zouching, and Fangzi, which, along with his treatise, have been kept on display in Apostolic Palace since 2017 in a show of Interfaith dialogue by Pope Joseph I. Intharatcha was unaware that his efforts had been in vain, however, as his returning ambassadors falsely informed him that both Francois and Urban had converted, something which pleased him greatly. Sotirians remained in high-standing in his court, and that of the short reign of his successor, a policy which would not continued by later Kasi monarchs.

Warfare

Grand Army

The creation of the Khaunban Empire had primarily been through military means, and lacking longevity or legitimacy outside of its constituent rulers' personal ties to Intharatcha, required a strong military to remain consolidated. At the start of Intharatcha's reign his army was largely composed of Kasi peasant levies, supported by cavalry, largely from the nobility, and a small elephant corps. It was with this army that Intharatcha was able to overthrow Sippommese rule of Khaunban and establish Khaunban as the new power in the Lueng river valley. This small nucleus would form the basis of the later ' Grand Army' (kongthap thiyingyai)

As the empire expanded so did the diversity within the army. The majority of the levies remained ethnically Kasi, but they were joined by Nainanese, Svai, Kyin, and Nyaram conscripts, largely from subject kingdoms. In 1557 Intharatcha divided the levies between the thammada (basic, or general) troops, who were raised for a specific campaign for short-term cyclical periods, and the phiset (extraordinary, special) soldiers, who constituted one of the first standing professional armies in Kuthine history. The phiset soldiers were entitled to a monthly salary, were given a uniform, underwent three years of training, and were expected to serve a minimum of 15 years. Villages which provided a certain ammount of phiset soldiers were excluded from the thammada registry.

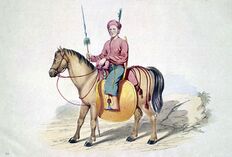

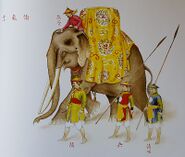

While the infantry levies formed the core of the army, the various special branches proved key for Intharatcha's continuing successes. These were the the elephantry, cavalry, artillery, and navy. The elephantry grew substantially with the army, becoming a major part of Intharatcha's war strategy despite never being more than one percent of his total force. The cavalry diversified into several branches, from light Myiang skirmishers to heavy Merket lancers. For artillery and muskets the Grand Army was largely reliant upon Gaullican and Estmerish merchants and mercenaries for cannon and officers respectively. Other notable mercenary regiments included Senrian veterans from the Soukou War, led by Tanaka Tunemasa, and cannonneers from the Aguda Empire.

In order to keep together a vast and ethnically diverse army, Intharatcha had to rely upon a competent officer corps. In his initial reign he was forced to rely upon the aristocracy and gentry for leadership, but as the empire grew he established a permanent Kalahom Department to oversee the training of officers and creation of strategy. Three of his five 'Gods of War', his most famed generals, Kriang Krai, Natthapong, and Chuthamani, came from peasant backgrounds and were able to rise on merit. The officer corp was equally as diverse as the army, with generals such as Vĩnh Nhật Tấn, Tanaka Tunemasa, Binnyadala, and Tian Thassapak achieving high rank and status.

During Intharatcha's campaigns in Shangea, his army expanded considerably both from the recruitment of local Shangean, and the addition of irregular conscripted bandit and rebel militias, as well as allied Jiao armies. In contrast to his earlier policies, these units were rarely mixed with the rest of the Grand Army and were often under the command of local leaders or allied Jiao generals. This was likely due to Intharatcha's lack of trust in the loyalty of these troops, many of whom had served under various dynasties and rebel leaders in quick succession.

The Gaullican Gervasius Jacquet, in his letter to Francois II, wrote that the army of "Indharache" numbered "in the millions" with "hordes of beasts and no less than 100 cannon". Though an exaggeration, at its peak the Grand Army may well have had a strength of over one million, although more conservative estimates vary its wartime strength between 300,000 and 650,000.

A Chanwan horseman from the Kingdom of Myiang

An elephant and accompanying crew from Nainan

Strategy

Battle Record

Death and succession

While in Juancheng in the midst of planning his next campaign into Shangea, he rapidly came down with a fever and within a week was dead. His sudden death shocked his court, as he had been in perfect health. His death was kept secret for three weeks while his chosen successor, Borommarachathirat, moved to neutralise opponents within the court and imprison several of his brothers who may have had designs of their own. With the support of the Grand Army, Borommarachathirat secured the throne and announced his father's death on the 5th December 1673.

Borommarachathirat faced numerous revolts upon his accession to the throne, and was forced to rely upon his father's officials and commanders to quell them. Within a year of his accession both Nainan and Myiang attempted to secede, provoking harsh retaliations from Kriang Krai, who emerged as Borommarachathirat's chief minister. One of Intharatcha's 'Gods of War', Vĩnh Nhật Tấn, defected to Nainan in 1675 and would wage a guerrilla war against the Khaunban for a decade, eventually establishing his own Vĩnh dynasty in 1684. Borommarachathirat and Kriang Krai succeeded in holding the empire together until the former's death in 1682 during the Toki invasion . The empire would fully dissolve in 1685 with Kriang Krai's death.

Intharatcha's remains were cremated and interred in Wat Photaram, in Sippom (modern-day Chaoburi), where he is worshipped as the temple's phi wat (guardian spirit) and the city's lak mueang (town deity).

Family

Intharatcha is famous for his many consorts, taking many to consolidate personal political alliances with vassal states. He had five chief and senior consorts, and over 50 more junior consorts. The consorts, and their issue, were well documented and records survived in various temples patronised by the king. They were immortalised in Mengrai's 1712 epic poem Yai Intharatcha, where they featured prominently in court life, and some, in highly fictionalised portrayals, were popularised in worldwide in the 1766 Guillaume Lancier's play The Merry Wives of Indarache.

Equally as high was his issue, having 94 children. Many of his sons were utilised as governors, installed as kings of subordinate realms, or served as military commanders. His daughters were largely married off to nobles and foreign monarchs. Some predeceased him, including his first son Norrapan. A dozen were taken hostage by the Toki dynasty after the sacking of Khaunban in 1682, with only a few managing to later return. Through them a large amount of people across Southeast Coius can trace their lineage back to him.

The following is a list of his consorts and their issue.

| Consorts | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Consort | Rank | Issue | Notes |

| Neungluthai | Chief queen | Norrapan | |

| Thao-Ap | Senior queen | Borommarachathirat | |

| Liu Nüying | Senior queen | Chariya | |

| Tanaka Sai | Senior queen | ||

| Thảo Liên Hoa | Senior queen | ||

| Sangrawee | Junior queen | ||

| Intira | Junior queen | ||

| Chanhira | Junior queen | ||

| Boon-Nam | Junior queen | ||

| Khun Mae | Junior queen | ||

| Prisana | Junior queen | ||

| Saengdao | Junior queen | ||

| Waralee | Junior queen | ||

| Zung Cer Maw | Junior queen | Chin | |

| So Kunthea | Junior queen | Khmer | |

| Iv Makara | Junior queen | Khmer | |

| Chhit Sotearith | Junior queen | Khmer | |

| Moul Nearidei | Junior queen | Khmer | |

| Eindra Khin | Junior queen | Chanwan | |

| Yadanar Zar Hayma Htet | Junior queen | Chanwan | |

| Nhin Hsu | Junior queen | Chanwan | |

| Thida Kyaw | Junior queen | Kyin | |

| Nandar Hlaing | Junior queen | Nyaram | |

| Amarindra | Junior queen | Nyaram | |

| Osoet Pegua | Junior queen | Nyaram | |

| Binnyathau | Junior queen | Nyaram | |

| Hešeri Alioth | Junior queen | !Manchu | |

| Ongchijin Khojin | Junior queen | Merket | |

| Bayad Nergüi | Junior queen | Merket | |

| Arinya | Junior queen | Thai Isan | |

| Wonnapa | Junior queen | Thai Isan | |

| Sawatdi | Junior queen | Thai Isan | |

| Rampha | Junior queen | Thai Isan | |

| Saowatharn | Junior queen | Thai Isan | |

| Sirindhorn | Junior queen | Thai Isan | |

| Jeloka | Junior queen | Cham | |

| Serenbah | Junior queen | Cham | |

| Guntirala | Junior queen | Cham | |

| Muluke | Junior queen | Cham | |

| Pandasanh | Junior queen | Cham | |

| Sái Quỳnh Dung | Junior queen | Nainanese | |

| Thảo Thúy Hương | Junior queen | Nainanese | |

| Thảo Thi Cầm | Junior queen | Nainanese | |

| Triệu Diệu Hương | Junior queen | Nainanese | |

| Chử Thùy Uyên | Junior queen | Nainanese | |

| Đặng Thúy Huyền | Junior queen | Nainanese | |

| Văn Minh Thủy | Junior queen | Nainanese | |

| Liu Daiyu | Junior queen | Shangean | |

| Liu Cuifen | Junior queen | Shangean | |

| Liu Lijuan | Junior queen | Shangean | |

| Liu Jingfei | Junior queen | Shangean | |

| Liu Xiaodan | Junior queen | Shangean | |

| Liu Jinjing | Junior queen | Shangean | |

| Xiang Zhilan | Junior queen | Shangean | |

| Liu Meili | Junior queen | Shangean, unrelated to imperial Liu clan | |

| Cai Zhenzhen | Junior queen | Shangean | |

| Ren Huiqing | Junior queen | Shangean | |

| Som Chai | Junior queen | ||

| Nisarra | Junior queen | ||

Legacy

Criticism

to be redone Intharatcha is considered one of Kuthina's greatest kings and its founding father. He is largely celebrated for his military exploits, having brought much of Southern Coius under Kasi rule. This is true not only in Kuthina, but also Shangea, Siamat, and Nainan, where he is considered the archetypal soldier-king. His ingenuity, unusual tactics, attentiveness to detail, and willingness to modernise and adapt, has made him a figure still studied for his strategies. His useage on Kuthine propaganda has in recent decades lessened his reputation in Shangea and Siamat, though he remains a relatively popular figure in the former for having fought against the Senrian Toki in favour of the native Jiao dynasty. He is also held responsible for contributing to further death and destruction, including targeted massacres and sacking of cities, during the Coius' Crisis of the 17th Century.

His reign represented a short-lived Zohist renaissance in Southeast Coius. Zohism had largely been on the retreat after Badi began spreading into the area after the turn of the 1st millennium. Kasi monarchs in particular had championed the new faith over the Zohism associated with the decadent and decaying Svai Empire. Intharatcha is considered by many Zohists to have saved it from a slow extinction, and to have given it a new prestige making it suitable for adoption by the Kasi nobility and royalty. While Kasi successor states would largely be Badist, they, and the people, continue to honour Intharatcha as a Chakela and a national deity.

While lesser known than his military exploits, Intharatcha contributed a great deal to political and cultural developments in Kuthina. His unification of the Kasi kingdoms of the Lueng and Moei rivers endured under the succeeding Mahadabao Kingdom. His ongoing integration of the Kyin and Lue states into the Kasi sphere was also continued by his successors. His patronage of tankenhei resulted in the mixing of Senrian and Kasi culture, particularly in the Lueng delta, and more than 10% of Kuthina's population are of Senrian descent. Despite this the majority of his innovations and policies died with his empire in 1685.

Propaganda and memory

detailing how he was viewed by contemporaries, and how he is used by Kuthina in modern-day propaganda