User:Tranvea/Sandbox Misc

| Normalisation Modernisation and Harmony Campaign | |

|---|---|

| Part of Zorasani Unification, Rahelian War, Irvadistan War | |

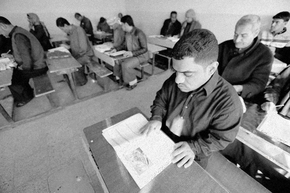

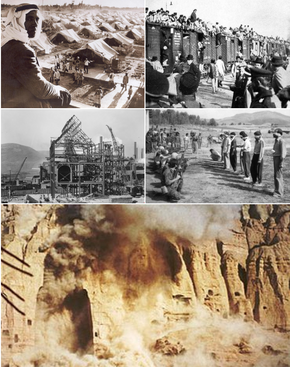

From top-left clockwise: A resettlement camp in Khazestan (1956); Togotis being transported by train to Lake Zindarud; Rahelian tribal leaders before a firing squad (1979); the destruction of the Great Zohist Monument in southern Pardaran (1982); Construction of one of many factories in new industrial cities | |

| Location | Union of Khazestan and Pardaran, Zorasan |

| Date | 1951-1988 |

| Target | Political opponents, Gâvmêšân, ethnic minorities, and occupied territory citizens |

Attack type | population transfer, ethnic cleansing, forced labor, genocide, classicide, |

| Deaths | 980,000-3,980,000 |

| Perpetrators | Zorasani Revolutionary Army, UCF |

| Motive | Modernisation, industrialisation, urbanisation and internal stability |

The Modernisation and Harmony Campaign (Pasdani: کرزیر نوژزه و توفیق; Kârzâr-e Nojāze va Tavāfogh; Rahelian: حملة التحديث والانسجام; Ḥamlat Taḥdīṯ al-Insijām) was a thirty-seven year state campaign conducted between 1951 and 1988 by the Union of Khazestan and Pardaran, and its successor state, the Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics, aimed at stabilising and modernising the country. It ran from the beginning of Zorasani Unification and eight years after its completion, and involved the forced relocation of ethnic minorities, ethnic cleansing, cultural genocide, rapid industrialisation, urbanisation and classicide. Between 1950 and 1988, an estimated 16.4 million people were relocated from their homes to different regions of the country, of these, roughly 8.2 million were forced to live in new industrial cities and new agricultural lands, while numerous cultural norms and systems were dismantled, including Rahelian tribes, nomadism and the repression of minority religions. By its end, between 980,000-3,980,000 people were killed directly or indirectly during the campaign, urbanisation rose from 15% to 64% by 1988 and Zorasan emerged as one of the most industrialised countries in Coius.

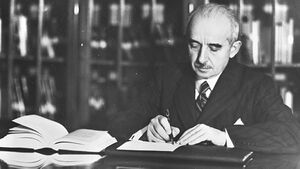

The Modernity and Harmony Campaign was devised by the government of Mahrdad Ali Sattari during the late stages of the Pardarian Civil War as a means of rapidly modernising the nation, to prevent the return of the colonial powers and to provide the state with the economic and industrial base from which it could militarily achieve unification. Sattari and his inner-circle identified a variety of "obstinate elements" of Zorasani society and culture that held the nation back from modernising into an economic and political powerhouse, this included certain ethnic minorities, the Rahelian tribal system, Steppe nomadism, wealthy landowners and their political opponents. The ruling ideology Sattarism, included a focus upon what it termed "modernity" (Ḥadāṯa), this was an all-encompassing term denoting the necessary adoption of technology, science and industry as well as the corresponding social changes needed to achieve "modernity." Sattarism also blamed these "obstinate elements" for the Etrurian conquest of Zorasan and Euclean domination, and would need to be destroyed to avoid a repeat. The targetting of ethnic and religious minorities for relocation was justified under claims that these "strategically placed peoples" would be most resilient to unification and adoption of a unifying Zorasani culture and indentity, therefore their homelands or areas of concentration would need to be broken up. The primary targets for relocation were Togotis, Kexri, Chanwans, Yesienians and adherents of Badi, in most cases hundreds of thousands were displaced and their former homes resettled by either Pardarians or Rahelians as a means of diminishing their concentration within geographical areas. Those displaced were re-setteled thousands of kilometres away, in either pre-built housing districts around new agricultural lands or industrial cities, or in some cases, forced to construct their homes from scratch in isolated areas. From 1958 to 1981, the campaign targetted perceived enemies of both the state and the campaign itself, who the government dubbed Gâvmêšân (Pasdani for Buffalo, in apparent reference to their "stubborness"), this group included tribal leaders, critics of the Sattarist state, socialists, wealthy peasants and shepards, monarchists and those related to the Pardarian, Khazi and the northern Rahelian royal families; the latter targeted mostly during the Rahelian War.

The campaign began to drawdown by 1985 and was officially dissolved in 1988 by order of the Central Command Council, which proclaimed the Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics, "unified, stabilised and introduced to social harmony." While the campaign delivered rapid urbanisation, industrialisation and modern technologies, it also significantly disrupted the lives of millions, who were evicted and transported away from their communities or places of birth. The attacks on cultural uniqueness of the various minorities has led many to accuse the campaign to have engaged in cultural genocide, while the cost in lives from both direct violence and indirectly through resettlement has led others to describe a viable case of ethnic cleansing and genocide. The replacement of resetteled minorities by Pardarians and Rahelians also draws much continued condemnation. Today, it is a criminal offence in Zorasan to refer to the campaign as a crime against humanity.

Background

Sattarism and Modernity

The overriding origin of the entire campaign was the ideological influence of National Renovationism. Developed during the Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command’s period of exile in northern Shangea, it adopted what Akbar Salami describes as the “Cult of Science and Industry”, which in turn was conceptualised as “Hadatha” (حداثة) – a Rahelian word meaning ‘newness’ or ‘modernity.’ Hadatha and its ‘Cult of Science and Industry’ would encapsulate the National Renovationist view that the more industrialised and technologically advanced a country was, the more powerful it was compared to others. Modernity, therefore, was written as a reaction to the Etrurian conquest of Zorasan – Etruria was more industrialised and advanced compared to the Gorsanid Empire, which in turn was condemned as backward, sentimental and too de-centralised to confront or defeat the encroaching colonial powers. If Pardaran, and later Zorasan, was to survive a return of colonialism, it would need to rapidly industrialise and modernise to reduce the gap in national power. From Modernity or Hadatha, would spring forth all subsequent actions and plans of the Campaign, including the eradication of agrarian ways of life, nomadism, tribalism and in the extreme, select minorities deemed to be a threat to modernisation or societal cohesion.

Akbar Salami, a leading historian on the Campaign explains that the desire for modernity would require a complete transformation of society, from an agrarian one culturally and societally wedded to the soil, into an urban and industrial one. This he believes, explains the often-violent plans to eradicate cultural norms intrinsically linked to agrarian life.

Salami and other leading researchers have also argued that this transformative campaign was also envisioned as a means of establishing a new “modern society”, implementing Ettehâd and abolishing the “old divisions and sentimentalities” that condemn Zorasan to colonial rule. Through the transformation of society and its adoption of modernity, a collectivist, totalitarian society could be constructed in which the labour and activity of all citizens is dedicated to the greater good of the state and population, and a society in which the needs of the individual are sacrificed voluntarily.

The founding of the Union of Zorasan in 1952, also influenced thinking toward the Campaign, notably, Mahrdad Ali Sattari’s repeated fears of the vast oil and gas reserves held by both Pardaran and Khazestan – he feared this would further entice Euclean powers to return, but also with some degree foresight, feared a wilful dependence on petrochemicals for state finances. He described petrochemicals on numerous occasions as the “Black Opium”, and saw industrialisation as a means of averting both scenarios. The Black Opium moniker would define Zorasani economic policy for the next 70 years to this day.

Legacy of Euclean colonial rule

Beginning in the early 1820s, the Gorsanid Empire was slowly subjugated primarily by Etruria, this process initially began with the seizure of At-Turbah and Zibakenar in 1821 and 1822 respectively as a means of combating corsairs that attacked Etrurian shipping in Solarian Sea. Through these occupied ports, the Etrurians steadily forced open the Gorsanid Empire into one-sided trade agreements, ostensibly for Etruria to secure a monopoly on trade altogether. In 1839, the Etrurians occupied the Riyadhi Peninsula following a failed local uprising, this was followed in 1843 with the occupation of the entirety of Irvadistan in the First Etruro-Gorsanid War, as well as the cities of Chaboksar and Ashkezar. This led in 1849 to the near outbreak of war between Etruria and the Kingdom of Estmere over the formers efforts to achieve monopolisation, leading to the Treaty of Virgillia, which forcibly granted Estmere control over the Gorsanid port cities of Khusavar, Bandar-e Sattari and Bandar-e Daryush, in exchange, Etruria was granted rights over the remaining territory of the Gorsanid Empire. This culminated in the Second Etruro-Gorsanid War (1852-1858), which began with the assassination of Shah Akbar Reza II by his brother Fereydun Reza I, who then instigated a series of attacks on Etrurian-held territory. Vastly outmatched in terms of technology and military training, the Gorsanid Empire ultimately collapsed with the occupation of the entire empire under Etrurian rule, this was formalised in the 1860 General Solarian Ordinance, which divided the Empire into two Dominions of Cyracana and Rahelia Etruriana, and two Protectorate-Generals Ninavina and the rump Pardarian monarchy, the Sublime State of Pardaran under the Zarafshan dynasty. As Protectorate-General, the Sublime State would provide Etruria with exclusive trade access and submit to total Etrurian control over its resource development, infrastructure, defence and foreign policies, while retaining control over several internal affairs.

From 1860 to 1941, there was little in the way of difference between how Etrurian approached the economies of both its Dominions and Protectorate-Generals, a reality that would be consistent under both the monarchy and Second Republic, though the political realities would differ considerably over time. Etruria unlike its peer colonial powers did not engage in settler colonialism, rather that sought solely to militarise its colonies and focus on resource exploitation and development. Though they found no discernable industry within the Gorsanid Empire by 1860, they did however, discover a vast territory of fertile farmland, thick and lucious forest and rainforest and deposits of coal, iron ore, copper, tin and gold. Petrochemical reserves would be discovered in the late 1930s, but the Solarian War would limit development to select fields off-shore and on-shore in Khazestan. As such, Etrurian colonialism was driven by the need to extract resources for processing and refinement in metropolitan Etruria, including foodstuffs, coal and iron ore which fuelled Etruria's industrial revolution. Overtime this would lead to great disparities between coastal Zorasan and the interior, with Etrurian development being near-exclusively focused on the port-cities and the infrastructure linking them to the resource rich interior and farming regions, while simultaneously, maintaining the agrarian-centric way of life found prior to the conquest. Furthermore, the Etrurians only mechanised cash crop estates to boost productivity, leaving many staple crops farmed in ways unchanged for centuries. This resource intense policy would leave Zorasan in 1946, with an overwhelmingly rural population, the among the lowest rates of literacy among the post-colonial nations and once vibrant mining and farming industries bereft of the technology, management and financial support it had come to depend on.

This meant, that upon the onset of the Campaign in 1953, the National Renovationist regime would be tasked with lifting the country at least 100 years behind the Eucleans into the modern age at breakneck speed, if to avoid the near-paranoid fear of the Euclean powers returning to reassert hegemonic control over the post-colonial world.

Initial plans

Plans to begin a modernisation campaign were initially drawn up in 1947, shortly before the outbreak of the Pardarian Civil War. A series of meetings of the Union Command Council in the summer of that year, identified the foundations of what would later be used in 1953 – the need to transfer populations to cities, to boost power production and water supplies for those cities, modernise and expand infrastructure, mechanisation of all agricultural lands and to boost output of capital goods, consumer goods and {[wp|construction materials}}, all the while, boosting output of resources to supply industrial needs, export those resources for the securing of financial assets and doing so without overly disrupting economic life.

It was also during these meetings the Modernisation Campaign also steadily took up issues relating to ethnic and sectarian minorities living in Pardaran. Many members of the Command Council expressed concern that certain groups would pose greater threats to modernisation than others, while some used this as a cover for more chauvinistic prejudices against those minorities. In a series of Command Council reports distributed across the National Renovation Front throughout 1947 and 1948, it was revealed that the Front feared those it described as Xareji (translated into either ‘Alien’ or ‘External’), those who did not “conform to the realities of Pardarian life.” These included Zoro-Satrians, brought over from Satria Etruriana under the Etrurian Second Republic, Yeniseians, Chanwanese, Badists, Sotirians and Zohists. In a report dated July 1948, the Command Council agreed, “the establishment of a modern, industrial and martial society is best achieved through the absence of the External, for cohesion of the spiritual and national forms.” These concerns would be carried over to the 1953 Command Council Decree that launched the Campaign and the plans themselves, indicating a pre-meditation to the massacres that would take place against these groups.

The original 1947-48 reports also identified the need to secure foreign support and expertise to facilitate the campaign, especially in the design of new industrial cities, power plants and factories. At this time, the PRRC was not recognised internationally, particularly the victorious allies of the Great War and Solarian War, with the latter having recognised the Sublime State of Pardaran as the sole legitimate authority over non-Rahelian Zorasan. This would change with the founding of the Union of Zorasan in 1952, where the Union secured support from the All-Soravian Union of Republics and Werania in the development of cities, factories and infrastructure.

The initial plans also laid the groundwork for the necessary literacy drive. Owing to the nature of Etrurian colonial rule, literacy in post-1946 Pardaran was a mere 20.69%, though this rate rose to 26.46% when including Khazestan and Ninevar. The literate population was limited to the port cities and civil servants among the Pardarian, Khazi and Kexri Republic elite, it was determined that in exchange for assisting in the literacy drive, this elites would be spared imprisonment or execution. The PRRC’s military forces were also notably literate and constitute the core of the drive, with soldiers and officers dispatched across the country to teach reading and writing to adults and children, even as those adults were being resettled and tasked with building cities and factories. This was expanded in 1948, to include the establishment of technical institutes to educate a new class of engineers and workers, again, even as they assisted in the physical building of the factories that would employ them.

However, these plans would be put on the hold with the onset of the Pardarian Civil War (1948-50), the Khazi Revolution in 1952 and the intervention in the Kexri War which would all lead to the founding of Union of Zorasan of Pardaran, Khazestan and Ninevar.

1953 Union Command Congress and Khomentah

Following the end of the Kexri War, the countries of Pardaran, Khazestan and Ninevar united to form the Union of Zorasan, re-establishing the first unified Zorasani state since the Etrurian conquest on 2 December 1952. On the 3 January 1953, the first Union Command Congress was held in Faidah, where the plans for modernisation drawn up by the Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command between 1947 and 1948 were presented. The plans were met with excitement among the delegations from all three Union Republics, and on the 4 January the Command Congress voted to approve the plans, appointing Hossein Khalatbari by vote, as Union Minister for Modernisation and Harmony. Under direction of Supreme Leader of the Union Mahrdad Ali Sattari, the Command Congress also approved the establishment of the Union Committee for Modernisation and Industry (خمیته اتحاد نوجوان و توفق; Khomiteh-ye Ettehad-e Nojāze va Tavāfogh; known by its acronym of Khomentah). Khomentah would go on to serve as the umbrella body tasked with overseeing the Campaign until 1988, it would be granted considerable power over provincial governments, resources and manpower, though would remain accountable to the Union Command Council alone. Khomentah would also operate four sub-committees, literacy, industrialisation, urbanisation and harmonisation. The organisation also boasted unfettered access to the Union Ministry of Finance, Union Ministry of Mining and Forestry Affairs and the Union Minister of Labour and Mobilisation, within months of the Campaign's beginning, these ministries would all but become subordinate to Khomentah.

On the 10 January, Khalatbari as the newly minted Union Minister for Modernisation formally established Khomentah in Zahedan. Granted extraordinary powers by the Union Command Congress, Khalatbari with assistance from Deputy Union Minister Qadir al-Suwais established an administrative framework for Khomentah, its subordinate bodies would be comprised of Province Committees (خمیته استان; Khomiteh-ye Ostân; KHOMOTAN), each chaired by a Governor-General (استاندار; Ostândâr), these Governor-Generals would hold ultimate power over their respective provinces, subordinating the provincial central committees entirely. The Khomotans would provide Khomentah with all necessary data, progress reports and would serve as the coordinators for local efforts. The Khomotan, like its umbrella body, would be sub-divided into four sectors covering literacy, industrialisation, urbanisation and harmonisation. However, in 1958, harmonisation would be transferred entirely to the State Commission for Societal Protection.

From mid-January through to early June 1953, Khomentah conducted a widespread study, collating the works of prospectors, geologists, urban planners and the first newly arrived advisers from Shangea, All-Soravian Union of Republics and Werania. The completion of this study was dispatched to the Union Command Council on 10 June for review, on the 13 June, the Command Council authorised the study and the Campaign was officially launched.

The campaign

First Phase 1953-1958

The First Phase (اَوَّل مرحله; Marhale-ye Avval) began on the 13 June 1953 and would continue until the 13 November 1958 and would see dramatic results. Notably, the Campaign was not defined by arbitrary objectives or quotas, but rather by end dates – the Command Council was averse to instilling rushed efforts or promoting dishonest reporting by Khomentah, as the principal drive behind the Campaign was ideological and not pressing fears of conflict or invasion, there was a ‘culture of comfortability’ around the pacing of industrialisation efforts.

The First Phase is defined by its mass deportations of populations, rapid industrialisation (though at rates below expectations), dramatic increases in literacy and urbanisation. The Phase is also defined by the Zorasani-Satrian genocide, creation of the Habsedar prison camp system and crackdowns on cultural norms and traditions in rural areas.

Industrialisation

To facilitate popular engagement, the Command Council and Khomentah initiated a widespread propaganda campaign, including posters, newsreels (displayed in communal theatres), Irfanic clerics, National Renovation Front cadres and the newly formed Popular Mobilisation Front. This campaign resulted in considerable support and mobilised the population for the Campaign, especially in areas not targeted for re-settlement. There was no shortage of cheap labour, owing to the country’s relatively large population and the eager of many rural inhabitants to pursue means of escaping destitution and subsistence living. Across the numerous Khomotan areas, millions of peasants and urban dwellers participated by building hundreds of factories, power plants, laid new roads and railroads often by hand or using rudimentary tools. Khomotans under government order, mandated working in three shifts with no rest day, except for religious obligations. The Khomotans operated a differing pay and reward scheme depending on the workers’ objectives, for example, workers building steel mills were rewarded with extra money for completion ahead of schedule, while workers constructing and expanding mines were rewarded with days off and improved food rations.

From 1953 to 1956, 380 facilities were constructed and opened, of which 20 consumed half of all financial investments. With the assistance of foreign expertise and specialists, a number of major projects were completed: Rawanduz Dam, the metallurgical plants in Dinavar, Abu Zayda, Eskandan and Zaravan. The cement plants in Fereydunekar and Borazjan, two large tractor and farming machinery plants in Kiashahr and Bakhdida. With Weranian assistance and investment, the Al-Qasim Refinery was completed by 1958, then the largest petrochemical facility in Coius, a 32% expansion on Khazestan’s on-shore oil and gas fields was also completed. Alongside these capital good facilities, between 1953 and 1958, a further 500 consumer good facilities were opened, primarily textile mills, two new automobile and locomotive plants were built in Zahedan – these would lay the foundations for Zorasan’s drive for diversification away from petrochemical dependence in coming decades.

To assist in the expansion of cities and heavy industry, considerable resources and manpower were devoted to the modernisation of the power grid. The government was keen to deliver 24-hour electricity to 45% of the population by 1958, though it would achieve 37%. To achieve this, Khomentah oversaw the construction of fourteen coal powered plants and two major hydroelectric dams (Rawanduz and Qashanrud) with Soravian assistance. At this time, domestic oil and gas production was diverted near exclusively for export to facilitate the earning of capital for the import of machinery and construction materials. This would result in a boom in coal mining across western Pardaran, with the establishment of two new coal mining efforts which employed 100,000 people in total.

To achieve this massive economic and industrial growth, the Union had to reroute and concentrate essential resources to the ever-growing needs of heavy industry. 85% of all investment made was focused on the heavy industry and mining sectors, with programmes deemed unnecessary slashed or removed outright from the Union’s budget for the six-year period. During the 1952-1958 period, due to the sheer percentage of resources going toward industrialisation, many basic goods, such as food and even clothing became scarce. Food especially, was subject to a National Rationing System overseen by the National Liberation Army, this was to both offset the resettlement of rural citizens to cities, forced deportations of often productive peasants and to support the larger rations handed to industrial workers – deemed essential for national development. This in turn would see the rise of the Bonyads in Zorasan, with Bonyad Emam Parastar emerging as the largest and most influential Irfanic charitable organisation. During the six-year period, the industrial workforce rose from 1.1 million to 4.03 million, establishing a new industrial working class within Zorasan, one that would constitute the government’s “ideal”, it would also lay the foundations for the eventual emergence of the modern day political-culture of Zorasan.

Industrial Cities and urbanisation

Upon the Campaign’s launch in 1953, Zorasan has one of the least urbanised populations in Coius, with only five cities with populations exceeding 500,000 out of a total population of 35 million. This was widely accepted as insufficient to facilitate industrialisation on the scale required, as such, Khomentah with the assistance of urban planners devised schemes to establish new “Industrial Cities” (صنعتی شهرها; Šahr-hâ-ye San’ati), all of which would be “Single Industry-Towns”, dedicating to metallurgy, chemicals, processing materials or conversely, dedicated the mass production of light goods. Many of the planned Industrial Cities were centred around existing urban areas, though several notable exceptions include Dinavar, Savan-e Javid, Dar Huzan and Veshtan, which were built from scratch. Many of the Industrial Cities were located along existing railroads or near areas rich in natural resources, enabling processing, manufacturing and the housing of miners.

Despite initial calls, urban planning with regards to providing overly green or ideological aesthetics was rejected as “ostentatious” and a waste of time, as a result many of the Industrial Cities developed or built outright were often built in such a manner that placed the industrial facility or facilities at the centre and all infrastructure, housing and amenities built around it.

The Campaign’s First Phase also included plans to significantly expand the cities Borazjan, Ashkezar, Zahedan and Faidah. This included plans to grow Zahedan’s population from 750,000 to 1.85 million by 1958, however, the population would exceed targets, reaching 2.01 million by 1957. Administrative failures and blunders would often lead to resettled peoples being dispatched to these cities without sufficient housing to receive them, leading to the emergence of slums and overpopulation. Even in cities built from nothing, the living conditions were poor or worse – in Dinavar, a family of four or five (parents and children) would be forced to share a single room in a new apartment building, often without working electricity or water due to these utilities being unfinished by the time of inhabitation. In other cases, such as the development of Eskandan, cities were built far quicker than anticipated, without sufficient infrastructure to handle the supply of food, leading to periods of even tighter rationing. The lack of organised and standardised healthcare also resulted in Industrial Cities witnessing the outbreak of disease and sickness, this would lead to reformed procedures for urbanisation in all future Phases of the Campaign. Between 1953 and 1958, an estimated 85,000 people died as a result of treatable diseases, starvation or the effects of unsanitary living.

The rapid urbanisation and expansion of cities often came at the expense of long-term planning, with the provision of drinking water being a prominent issue, one that has only worsened by the 21st century, with numerous cities in Pardaran regularly reporting water shortages during summertime. This issue is exacerbated by the focus on supplying industry and agriculture with water, which in turn relies upon transportation systems built during the Campaign. The development of the Industrial Cities was supported the forced resettlement of millions of people from the Great Steppe and Ninevar, however, it has been noted by historians that the displaced peoples, who were tasked with building the cities they would never leave and dedicate their working lives, built homes exceedingly more modern from their original homes, only to discover these homes were for them. According to the historian Said Ali, “the Kexri or Togoti laced with hateful fury would find themselves building a home with bedrooms for all their children, a working kitchen with electricity and water, only then to see their fury fade somewhat as they were handed the keys to the home they just built.”

The expansion and construction of Industrial Cities had a profound impact on the natural environment. Dinavar for example was built within thick forest, which left over 100 km2 cut down, which numerous natural habitats were destroyed, leaving a lasting impact on ecosystems and animal species.

By the end of the First Phase in 1958, the number of people living in towns and cities within Zorasan had risen to 12.5 million, and the number of cities with populations exceeding 500,000 had risen from 5 to 18.

Literacy

One of the most serious weaknesses of Zorasan at the launch of the Campaign was its dire rate of literacy, of only 24%. To build a new industrial working class and to unleash the potential of modernisation, the Union-Government understood the need for rapid and dramatic increases in literacy. As such, a literacy drive became one of the most prized elements of the Campaign (a reality that would last until the 5th Phase). The Union-Government’s pool of literate citizens was limited and as a result turned near exclusively to Irfanic clerics, soldiers, officers and civil servants. Former Shahdom and Khazi royal officials, tribal and nomadic elders from the Steppe were promised amnesty or the avoidance of imprisonment if they assisted Khomentah in teaching reading and writing. In total, over 8,600 individuals were ‘mobilised’ to teach workers literacy as the workers built factories, cities or powerplants.

Using Soravian and Weranian experts, Khomentah also constructed and opened over 300 Technical Institutes across the country, to raise a new generation of engineers and managers. Simultaneously, over 1,600 schools were built, and primary education was introduced as a right with mandatory attendance for six years for rural communities and seven years for children in urban areas. Between 1953 and 1983, all schools in Zorasan were governed and run jointly by the military and Irfanic clergy. The need for specialist workers led to government funded scholarships to foreign universities and institutes, particularly to Shangea, Senria, Werania and Soravia. Notably, the literacy drives also coincided with a standardisation of language, particularly in Pardaran, with children taught the Zahedani dialect over the numerous Pasdani dialects found across the country. In Ninevar, in hopes of avoiding a resurgence in ethnic violence post-Kexri War, Rahelian students were taught Rahelian, while the Kexri were taught both Rahelian and Kurmanji. The peoples of the Steppe however, were forced to be taught Pasdani, it would not be until the mid-1970s, that Togoti would be taught as the “Third Language of the Union.”

Between 1953 and 1958, Zorasan’s literacy rate surged from 24% to 48%, though proficiency in maths was limited owing to the focus on reading and writing. The first literacy drive is also defined by its intense ideological nature.

Land Reform

One area of intense interest to the Union-Government was land reform. Following the collapse of Etrurian colonial rule, vast swathes of farmland were seized by elites closely linked to the Pardarian and Khazi monarchies, leading to 97% of ariable farmland in the Union of Zorasan being held by 6% of the population. This reality changed with the end of the Pardarian Civil War and Khazi Revolution in which elite-held lands were seized by the government. All farmland under the previous regimes and since 1950 and 1952, was rented back to poor peasant families, a situation that while beneficial to the Union-Government, was failing to see consecutive years of increasing yields of crops. Plans for land reform were introduced in the National Republic of Pardaran in 1950, but were stalled and ultimately shelved with the establishment of the Union of Zorasan in 1952. Debate erupted in early 1953 over the direction of land reform to take, with many within the Union Command Council wishing to retain state-ownership over farmland, against a faction who sought to return land to the farmers.

In late 1953, the Command Council agreed on a compromise, to retain state ownership over 60% of farmland, while significantly reforming ownership of the remaining 40%. On January 8 1954, the Command Council issued the Land Reform Edict, mandating that no one might hold more than 84 hectares (210 acres) of land, for farming, and that each landholder must either farm the land himself or with family, or rent it under specific conditions. An additional 42 hectares (105 acres) may be held if the owner had children or shared it with fellow farmers, any additional land had to be sold to the government. Farmers who opted to form cooperatives could merge their total lands and gain access to government leased equipment, such as newly produced tractors and other machines. The 60% of farmland under state-ownership mandated the forming cooperatives, which would share farming equipment, the rents paid to the government would consistently be marked as lower than the cooperative's costs of running, while other cooperatives took rent in the form of produce rather than money. The government-held land would also consistently under law take 70% of all produce, leaving the remaining 30% to be sold on the market.

The reforms though popular and leading to a threefold increase in production, was disrupted by the mass deportation or resettlement of populations to the cities and new farming regions.

Creation of the Habsedar

Resettlements, deportations and massacres

The role of forced resettlement of populations and the deportation of minorities away from their homelands was a fixture of the initial plans made during the late 1940s by the then-Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command. This included plans to purposefully “shatter the strongholds” of minority groups to deter any future rebellion. There had long been a belief among senior PRRC officials that the country’s various ethnic minorities posed threats to national stability and unity, drawn both from its claims of Etruria operating divide and rule to destroy the Gorsanid Empire and the rise of various nationalisms in Coius, post-Great and Solarian War. As a result, plans were drawn up in secret to forcibly resettle populations from the Pardarian Steppe to the interior, replacing these populations with Pardarians, this was expanded to include the Kharkestar Corridor, which was deemed to be of “upmost strategic interest.”

Plans for deportations and resettlements were significantly altered with the founding of the Union of Zorasan and the annexation of Ninevar. The plans altered not just in scope, but also came to focus more on the necessity of forcing urbanisation over depopulating historical homelands of minority groups. This prioritising of economic need over more nefarious intentions would cover much of the efforts, however, purposeful and malignant deportations of Zorasani-Satrians, Yeneisians and the Chanwanese would remain feature of the Campaign until its end in 1988. These deportations would result in significant loss of life and more often than not, saw these groups deported not to new industrial cities or fertile lands, but either to the Habsedar or near inhospitable regions.

Though an estimated 26 million people would be resettled or transferred over the course of the thirty-five year period, during the First Phase (1953-58) alone, an estimated 8 million people resettled, among these were an estimated 2.1 million people deported to labour camps or isolated and desolate regions of Zorasan. Though estimates vary and little to no official records exist, it is estimated that the resettlements resulted in the deaths of between 150,000 and 450,000 people in the 1953-1958 period, this also included numerous massacres conducted by the Zorasani military, such as the Khosravani massacre, Bezanjan massacre, Kulaq Kasan massacre and the Zhuzhila massacre.

To execute plans for resettlement, Khomentah established a subordinate organisation known as the Baxš-ye Savvom or "Third Section", which took its name from the third floor of the Khomentah building in Zahedan. The Third Section however was dubbed an "inter-service commission", owing to the involvement of the National Liberation Army and the General Intelligence Service. The Third Section was headed by Brigadier General Nasir Ahmad and subordinated by GIS General Ershad Khanlari, the distinctly militarised nature of the Third Section was selected over a civilian-party official to guarantee success of both the economic resettlement and "shattering of the strongholds."

Rural resettlements

The primary target strata of society for resettlement was the rural Pardarian population and the Khazi populace living in the north, close to the borders with the Zubaydi Rahelian Federation. In Pardaran, the Union-Government identified three regions in which resettlement was safe in terms of disrupting the national food supply and agricultural production, these regions were Mizarabad-Amin Abad (much of the modern day Beshistan Union Republic), Sandsar Plain and the Erfanshahr-Vashmazin Corridor. These regions, though entirely focused on agriculture provided only meagre supplies to the state and were distinctly subsistence in nature. This also applied to the northern Sharezan Plain, which at the time was beginning to experience the first touches of desertification. In total, these regions offered the Union-Government an estimated 10 million people for resettlement.

The first resettlement took place on the 18 September 1953 when 3,300 men, women and children from the villages of Dahralmizan and Payan in the Sandsar region of the Steppe, were taken by army transports to Sandsar. They were the first to be settled in the city’s tent housing – the men would spend the next year building houses and tenements before moving into newly constructed factories. According to government records and historical accounts, the resettlement was peaceful, though much of the villages’ livestock was destroyed. However, it is widely accepted that the recorded and broadcasted resettlement of the two Sandsari villages was a propaganda exercise, the military and government lacked sufficient motor vehicles to transport the sheer number of people required. For the overwhelming majority of those resettled from the countryside to the cities, it was done so by train or on foot. Zorasan’s limited rail infrastructure meant that trains were often overloaded with passengers, with belongings dispatched later if it all. The conditions aboard the trains were described as abysmal and hellish, with men and young boys often taking to riding on the roofs of carriages, leaving the interior for women, young children and the elderly. In numerous cases, rural populations close to new industrial cities were led by foot to be settled by the military, in these cases, thousands of elderly family members were left behind, despite government promises of future transportation for them to re-join their families.

Resettled families were permitted to take as many possessions as they could, though this was limited to money, clothing, photographs and jewellery. Food and water was provided to the resettled enroute to their destinations by the Third Section.

In many cases, government resettlement was met with violent resistance by rural communities. The Third Section issued procedures to its attached military units, ordering them to shoot-to-kill, kill the community’s livestock and burn the homes of those suspected of organising the resistance. If spontaneous, the units were authorised to select civilians for deportation to the Habsedar camps, execute others by firing squad as well destroy homes and livestock. Throughout the First Phase, the government denounced communities who resisted of engaging in “seditious sentiments” and “soil worship” and regularly affirmed its willingness to “execute those who would hinder the national path.” Violent resistance began almost immediately following the Sandsar resettlements, in virtually all cases of the Third Section’s military units being sent into rural communities, they would pre-empt resistance by violently rounding up peasants for transportation, this would lead to thousands of deaths across the Pardarian and Khazi regions. In other recorded cases, not only did Third Section soldiers kill people, they would regularly loot the homes of those being resettled, including the theft of family heirlooms and livestock. This in turn forced a Third Section review and the looting of homes was strictly forbidden, but rarely enforced.

In other cases, the Third Section relied upon cadres from the National Renovation Front to entice the populations of villages to acquiesce, through propaganda and near-utopian promises of the cities they were heading to. This became the common practice from 1955 onward, though it did not stop more forceful Third Section units from relying on violence over negotiation. Those communities who agreed to peacefully resettle, were often treated "remarkably well” according to Archibald Harrison, a travelling reporter from Estmere. He documented that “those denizens who acquiesced to be uprooted from all they knew were treated like family friends by the state’s enforcers. I witnessed soldiers carry old men and women, play with children during stop-overs, they regularly stopped our locomotive to guarantee fresh air entered the squalid carriage cars and never once did I see a man, woman or child left behind.” This would be in stark contrast to the violent resettlement seen in other cases across the regions.

Though subject to intense debate, it is more widely accepted that the government was able to entice rural peasants in Pardaran and Khazestan to acquiesce to resettlement through propaganda and the allure of improved living standards offered by the “new urban Zorasan.” The Union Command Council throughout the First Phase repeatedly expressed concern over the use of violence by the Third Section, forcing it to instigate a complete media lockdown to halt the spread of news of violence or killings by the military. Such was the success of the propaganda effort, that the government was forced to instigate travel restrictions on regions outside those selected for resettlement, as tens of thousands of families began moving independently to the cities as word spread. On 13 July 1956, the UCC introduced a ban on travel between the three Union Republics without authorisation, a ban that would last until 1972.

The killing of livestock and destruction of homes however became a cause for concern among government officials, with even Mahrdad Ali Sattari remarking in 1955, “perhaps it would be better to spare the oxen and swine.” Khomentah, under Sattari’s pressure amended the Third Section’s procedures, mandating the collecting of livestock and redistribution among the protected rural regions and state farms. This led to a hushed joke among Zorasanis in the late 1950s and 1960s, that a “pig is worth a family of ten.”

According to Said Halim’s estimates, approximately 10,000-20,000 people were killed by the Third Section in the forced resettlement of Pardarian and Khazi peasants. A further 35,000-70,000 were deported to forced labour camps or prison. He further estimated that up to 760 villages were entirely depopulated by the resettlement of peasants to the cities, while a further 200 were populated only by the elderly and infirm, without the support of their children or grandchildren, and having lost their livestock, they would often starve. Though Halim’s studies revealed that a majority of the abandoned elderly were eventually transported to their families in the cities or taken into government institutions.

Of the 10 million people residing in the four regions selected for resettlement, an estimated 5.9 million were resettled to the cities and new industrial cities over the course of six years, in what is one of the largest movements of people in world history. Of the 5.9 million, 3.5 million were resettled to construct and populate the new industrial cities, there they found access to education, healthcare and improved living standards. As part of the First and Second Phases, the Union-Government steadily introduced new rights for women, including the right to employment, literacy and a rudimentary form of maternity leave. The Union-Government also launched a significant campaign of innoculations against various diseases. The elderly and infirm who were left behind, were for the most part later transported to their families, while the government also constructed institutions for these people in the new cities.

Shattering the Citadels

The most infamous chapter of the First Phase was the Shattering the Citadels (Arg-hâ va Kerâšidan), a policy of forced deportation of ethnic minorities from their historic homelands to far-off regions of the country, ostensibly to repopulate their homelands with Pardarians and Rahelians. While in some cases this was to “secure regions of strategic national interest” such as the Kharkestar Corridor or the Mangarak coal fields from minorities of “questionable loyalty”, it was primarily driven by historic Pardarian chauvinism towards these minority groups, who were accused of insufficient loyalty to the state during the Etrurian conquest of Zorasan or were subject to conspiracy theories of harbouring separatist intentions.

The theory of Shattering the Citadels emerged within the mid-levels of the Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command in the months following the Coian Evacuation and the PRRC’s consolidation of control over southern Pardaran, including the Great Steppe. The chief advocate for the theory was General Yazdandad Jandhar, a hardline Sattarist and Pardarian Chauvinist, who held contempt for the Steppe peoples and Zorasan’s Satrian community. However, he mellowed toward the Togoti population owing to their support of the PRRC during the Solarian War. In a series of letters to Mahrdad Ali Sattari, inadvertently published in wake of the latter’s death in 1957, Jandhar repeatedly urged for the total expulsion of the Chanwanese population into Shangea and “Pardarianifcation” of the Yeneisian and Satrian populations, though this found little purchase with Sattari personally. In 1952, Jandhar published an article dubbed “Shattering the Citadels” in the exclusive internal newspaper of the PRRC, advocating for the “resettlement of Externals and Aliens to regions beyond their birthplaces, to reduce their demographic concentrations and to enable the resettlement of Pardarians.”

The situation changed with rise of Nasir Ahmad, a prominent member of the Khazi Revolutionary Resistance Command, who had worked with Jandhar and Sayyad Ali Gharazi in the Kexri War. Ahmad shared Jandhar’s hardline ideology and contempt for the Chanwanese and Satrian populations. In 1953, they were joined by Field Marshal Yadollah Shariatzadeh, the then-chief of the National Liberation Army and his acolytes, swaying the Union Command Council in the 1953 planning meetings into backing the Shattering the Citadels theory. Shariatzadeh was integral in the conflation of the theory with the UCC’s desire to destroy nomadism, tribalism and what was described as “External and Implanted Alien Traditions.” The appointment of Nasir Ahmad as head of the Third Section all but guaranteed its implementation.

The principal targets of the Shattering the Citadels campaign were the Zorasani-Satrians, Yeneisians, Chanwanese and to some degree the Kexri, though in the latter’s case, the justification was the lingering threat of rebellion and influence by the exiled leaders of the Kexri People’s Socialist Front.

Ninevar

Great Steppe

Zorasani-Satrians

Shattering of the Sentiments

Foreign assistance

Results

| Products | 1953 | 1954 | 1955 | 1956 | 1957 | 1958 | Total increase from 1953 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cast iron, million tons | |||||||

| Steel, million tons | |||||||

| Rolled ferrous metals, million tons | |||||||

| Coal, million tons | |||||||

| Oil, million tons | |||||||

| Electricity, billion kWh | |||||||

| Paper, thousand tons | |||||||

| Cement, million tons | |||||||

| Sugar, thousand tons | |||||||

| Metal-cutting machines, thousand pieces | |||||||

| Cars, thousand pieces | |||||||

| Leather shoes, million pairs |