Cutinsua

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

League of Five Cities Hunyu Pichqantin Llaqtakuna | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1324–1530 | |||||||||||||||||||

|

Attested banners of the League of Five Cities | |||||||||||||||||||

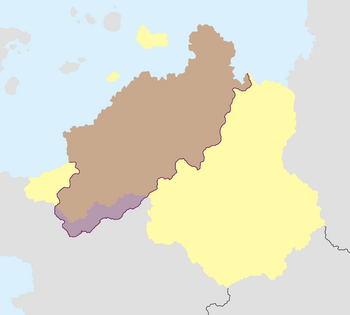

Cutinsua at its greatest extent, c. 1520, overlaid over modern Aucuria | |||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Andavaila (1324-1528, de facto) Čačapojas (1528-1530, de facto) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | Runanca | ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Kirua, others | ||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Cutinsuan religion | ||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Cutinsuan | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Hegemonic confederation of allied city-states | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hanan Qhapaq | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1324 - 1356 | Mankojupankis Pačakutekas | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1360 - 1393 | Atokjupankis | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1417 - 1438 | Ljokėjamaras | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1438 - 1480 | Čapatipomas Sinčijačekas | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1515 - 1528 | Javarjupankis | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1528 - 1530 | Kapakrokas | ||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||

• Formation of the League | 1324 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Conquest of Oruras | 1336 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1530 | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||

The League of Five Cities (Classical Runanca: Hunyu Pichqantin Llaqtakuna), more commonly known as Cutinsua (Classical Runanca: Sunquntinsuyu; Kirua: Lluquayllu), was an alliance of five Runanca city-states - Andavaila, Čačapojas, Suljanas, Lambajekė, and Akarajas - that ruled much of northern Aucuria from 1324 until its conquest by the Ruttish užkariautojas Jurgis Leikauskas in 1530.

The League of Five Cities was formed in response to the military expansion of the Kingdom of Oruras, which was perceived as an existential threat by its founding members. The League subsequently defeated and conquered Oruras in a series of wars, and expanded from its heartland in the Vaskaranas Mountains to control much of northern Aucuria through a mixture of diplomacy, assimilation, intimidation, and conquest. Though nominally an equal alliance between all five of the League's founding members, Andavaila quickly became the dominant member politically, economically, and militarily, steadily forcing the others into subsidiary roles.

At its peak, Cutinsua controlled almost all of northern Aucuria and some regions of northeastern Nuvania, and was a key player in Medasteria. Cutinsuan rule was hegemonic and often indirect, with local elites permitted to retain their titles if they paid tribute to the League and the leaders of polities that resisted replaced by semi-autonomous stewards appointed by Andavaila. Cutinsua developed a complex system of roads, inns, and warehouses to facilitate administration and trade, constructed monumental works of architecture, used knotted strings called kipu for record-keeping, and oversaw a flourishing of textile-making, metalworking, and agriculture. Notably, the empire functioned internally largely without money, with the exchange of goods & services handled through reciprocity and taxes paid through the mit'a and minka systems of corvée labor. Cutinsuan religion was highly polytheistic, centered around a litany of deities and sacred objects.

In 1528, Cutinsuan envoys met with Jurgis Leikauskas and invited him to Andavaila. While there, Leikauskas met with envoys from Čačapojas, Suljanas, and Akarajas who relayed to him their resentment of Andavailan dominance within the League. Leikauskas agreed to aid them in a rebellion against Andavaila, which saw forces from Andavaila and Lambajekė repeatedly defeated and Andavaila itself viciously sacked in October of the same year. Čačapojas, Suljanas, and Akarajas subsequently seized a leading role in a rump League of Five Cities; however, their relations with Leikauskas and his forces quickly broke down, and, by 1530, Ruttish užkariautojai had destroyed their former allies, completing the Ruttish conquest of Cutinsua.

While efforts were made to revive the League by several indigenous revolts, most famously the 1608-1612 Great Cutinsuan Revolt, none of these efforts were successful. Nonetheless, Cutinsuan and neo-Cutinsuan resistance to Ruttish and, later, Rudolphine colonialism became important symbolically to indigenous rights movements among the Runanca and Kirua in contemporary Aucuria.

Etymology

The official name of the polity commonly referred to as Cutinsua was the League of Five Cities (Classical Runanca: Hunju Pičqantin Laqtakuna), in reference to the five city-states - Andavaila, Čačapojas, Suljanas, Lambajekė, and Akarajas - which were its founding members. These five founding members were nominally co-equal within the polity, with later members being accorded a subordinate status; in practice, the alliance was dominated by Andavaila, which was the location of the League's official meeting site and its treasury.

Cutinsuans sometimes euphemistically referred to their polity as "the heartland" or "the core territories" (Runanca: Sunquntinsuyu; Kirua: Lluquayllu), as they believed it to be situated upon the middle of the world. When Ruttish explorers and colonists arrived in the region, they rendered the Runanca Sunquntinsuyu into Ruttish as Kutinsuja, which subsequently became the source of the English "Cutinsua".

History

Antecedents

[previous civilizations in the vaskaranas; pativilkas, kiljakoljas, tirakvas, piura, kulkincas]

Formation

The Runanca people are known to have been present in north-central Aucuria, practicing a semi-sedentary form of pastoralism, by the 12th century. Their exact relationship with the previous civilizations in the Vaskaranas is unclear; while they are widely agreed to be unrelated to the Kulkinčas culture (who spoke Močikas, a language isolate), debate exists about whether the Runanca might be related to the earlier Piura culture. Elena Kvedarauskienė and Samuel Lorenz, noting the location of the likely urheimat of the Runanca language in what is now Pakrashchia and Oroncota, theorized that the Piura & Runanca are the same people and that the expansion of the Kirua peoples in what is now Kunturiri forced them westward into Pakrashchia and Oroncota. However, other scholars - such as Augustinas Vingrys, Oljantas Lozoravičius, and Léandre Perrault de Vézelay - have argued that the Piura more likely spoke the now-extinct Pukvina or Leko languages, or noted that there is little tangible evidence to confirm a link between the Piura and Runanca.

By the 13th century, the Runanca were the primary population group in the region and had become overwhelmingly sedentary, settling in a network of city-states which were primarily located along major rivers in the Vaskaranas Range and its foothills. These city-states were generally headed by hereditary monarchs styled with the title qhapaq (literally "mighty one"), and some had been settled locations well before the Runanca shifted fully to sedentism. Among the city-states were Andavaila and Suljanas on the Čančamaja River, Lambajekė on its tributary the Nupė, Čačapojas on the Lukumaja, and Akarajas on the Žavaris; these five in particular quickly became some of the most prominent city-states, as their locations were ideal for agriculture, mining, trade, or some combination thereof. Concurrently, the southeastern regions of the Vaskaranas range, dominated by the Kirua people, were being unified by the Kingdom of Oruras. Known to have existed historically since 1252, Oruras rapidly established control over the basin of the Apurimakas throughout the 13th century and, by the end of the century, had extended its reach as far south as the upper reaches of the Japakanis River.

With control of its southern frontier secured, Oruras increasingly looked to extend its control over the Runanca city-states to its north, whose agricultural and mineral production would be a sizeable asset for any monarch who could establish their rule over them. Beginning in the 1310s, the Oruran king Čukivankas began to lead organized raids against nearby Runanca city-states, demanding that their leaders become his vassals and offer tribute to Oruras.

As Oruran expansionism became a matter of increasing concern for the Runanca city-states, the qhapaq of Andavaila, Mankojupankis, began to call for the creation of an defensive alliance between the leading city-states to resist Oruran aggrandizement. These efforts were largely focused on winning the support of other prominent city-states, as they would be able to bring smaller towns which had placed themselves under their protection to the alliance in the process. After Oruran armies attacked the town of Laurikočas - the farthest north they had struck - in 1323, the qhapaqs of Čačapojas, Suljanas, Lambajekė, and Akarajas agreed to Mankojupankis's proposal, and the League of Five Cities was formally established early in 1324.

Early expansion and consolidation

[mankojupankis pačakutekas, the repulsion & conquest of oruras, and the rise of cutinsua]

[tupakvalpas's unremarkable reign]

[atokjupankis v javarvakakas and the consolidation of andavailan hegemony]

[minor expansions under sinciankas, tupakukumarkis]

Later expansion and reform

[the wars of ljokeamaras and his sidelining]

[the conquests and reforms of capatipomas sinčijačekas]

[maitakapakis, ljaktakusaris, and the early years of javarjupankis]

Ruttish conquest

In April 1525, a small Ruttish fleet under the command of Jurgis Leikauskas, carrying 168 užkariautojai and 28 horses, arrived at the mouth of the Pautė River, within the territory of the League of Five Cities. The region where the Ruttish arrived was inhabited by the Nati people, and the initial interactions between the Rutts and indigenous Asterians were with nearby Nati kasikai, who were Cutinsuan vassals. These early interactions were largely unremarkable, with the Nati trading fish and local produce in exchange for Euclean tools, textiles, and glass, and the Rutts attempting unsuccessfully to persuade them to adopt Sotirianity. As a result, the kasikai treated the newcomers simply as a new set of participants in the established trans-Arucian trade network, and their arrival was initially regarded mostly as a curiosity in Andavaila.

The arrival of reinforcements in 1526, and of further reinforcements and the first Ruttish settlers in 1527, caused a breakdown of relations between the Ruttish and the Nati. A series of skirmishes ensued; these skirmishes were won by the Ruttish, and the kasikai subsequently sent a request to Andavaila for assistance. By this point, the Cutinsuans had become aware of the potential power of these new arrivals, as mercantile contact in the Arucian spread news of the destruction of Tzapotla by the Povelians and the installation of Mokumitsa as the tsatsa of Térachu by the Gaullicans. Accordingly, Javarjupankis decided in 1528 to send envoys to Leikauskas inviting him to Andavaila, in the hopes that he could obtain Ruttish recognition of his authority by resolving the dispute between the užkariautojai and the kasikai. Leikauskas, accompanied by 350 užkariautojai and 56 horses, arrived in Andavaila in April 1528. They were received by Javarjupankis and the league council at the Kurivičankas palace; translation was handled by Ieva Anacaona, the daughter of a Nati kasikas who had learned Ruttish after being given to Leikauskas's companion Henrikas Klimauskas, and Koljavazas, a courtier of Javarjupankis who spoke Nati. Negotiations between Leikauskas and Javarjupankis were largely ineffectual, as Javarjupankis insisted on the užkariautojai accepting him as their liege while Leikauskas insisted that Javarjupankis recognize the authority of the King of Ruttland.

As negotiations stalled, the envoys representing Čačapojas, Suljanas, and Akarajas on the league council approached Leikauskas and openly proposed that the Ruttish assist them in a rebellion against Andavailan hegemony in the League, promising to recognize Leikauskas's authority over the mouth of the Pautė. Leikauskas travelled to Suljanas in May 1258, telling Javarjupankis that he had been formally invited by the qhapaq of Suljanas and that he would return to resume negotiations in Andavaila shortly. In Suljanas, Leikauskas, qhapaq of Čačapojas Kapakrokas, qhapaq of Suljanas Atavjupankis, and representatives of qhapaq of Akarajas Vajnakapakas formalized the agreement. After the arrival of another 150 užkariautojai, 20 horses, and a cannon from Apvaizda shortly thereafter, the rebellion began. Upon receiving news of the rebellion, Javarjupankis began raising armies from those portions of Cutinsua still loyal to him; this included the forces of Lambajekė, led by their qhapaq Ninanamaras.

While small clashes between pro-Andavailan and pro-Čačapojan forces began almost immediately, the first large battle of the rebellion, and the first battle to see Ruttish participation, was the Battle of Laurikočas on June 27, 1528. The pro-Andavailan forces - unprepared to fight against gunfire, cannonfire, and cavalry - were quickly routed, and Ninamaras and the Andavailan general Kamjanjavis were killed. The remnants of the pro-Andavailan army retreated to Andavaila, which was subsequently besieged by the pro-Čačapojan forces. On October 30, allegedly due to a prophecy he had received from his chief priest, Javarjupankis decided that Andavaila's forces would meet the pro-Čačapojan army in open battle; during the battle, he was captured by the Ruttish, and Andavaila was brutally sacked as its forces disintegrated. Javarjupankis was tried for violating the privileges of the League's members by the rebelling qhapaqs and for heathenry, incest, and murder by the Ruttish; as he was in their custody he was sentenced by the Ruttish, who initially sentenced him to death by burning but reduced the sentence to strangulation after he agreed to convert to Sotirianity. Javarjupankis was executed on January 11, 1529.

Following Javarjupankis's capture, the surviving pro-Andavailan forces regrouped under the general Kavotoronkas and fled to Oruras, which was governed by Javarjupankis's brother Tupakarančas, who they proclaimed hanan qhapaq after Javarjupankis's execution. Kapakrokas, the qhapaq of Čačapojas, also proclaimed himself to be hanan qhapaq with the backing of Suljanas, Akarajas, and the Ruttish. The pro-Andavailan remnants and pro-Čačapojan forces met at Kulkapirvas in February 1529; both Kavotoronkas and Tupakarančas were captured in the battle, and Oruras was seized with little resistance shortly thereafter. Kavotoronkas was killed shortly thereafter, tortured to death by užkariautojai seeking the location of royal treasures he had hidden; Tupakarančas, like his brother, was tried and sentenced to death, but refused to convert to Sotirianity as Javarjupankis had and was burned alive in Oruras's main square. With the execution of Tupakarančas, pro-Andavailan resistance totally collapsed.

After two weeks in Oruras, the pro-Čačapojan army began to move north, planning to return to Andavaila, from where the Rutts would return to Apvaizda and the Cutinsuan armies would return to their home cities. On March 17, 1529, however, as this army rested in the town of Kailjomas, a dispute emerged between Ruttish and indigenous soldiers, with Ruttish soldiers claiming that the Cutinsuans had disrespected the materials of the Eucharist and Cutinsuan soldiers insisting that Ruttish soldiers had interrupted a ritual honoring a local wak'a. The precise escalation of events is disputed by colonial-era chroniclers, but it is agreed that the dispute turned into a battle in which much of the indigenous army was destroyed and the qhapaqs Atavjupankis and Vajnakapakas were murdered. Kapakrokas and his general Vaskaravalpas attempted to flee to Čačapojas to organize a defense there, but the Ruttish horsemen managed to outpace the fleeing Čačapojans, and a Ruttish ambush only a few days later saw Vaskaravalpas killed and Kapakrokas captured. After begging Leikauskas for his life, Kapakrokas was spared on the condition that he convert to Sotirianity, abdicate, and live in exile in Ruttland.

With the defeat of Kapakrokas, organized Cutinsuan resistance to Ruttish rule functionally collapsed. Užkariautojai spent much of 1529 and 1530 asserting Ruttish authority and mopping up scattered pockets of resistance and, by the end of 1530, the Ruttish conquest of Cutinsua was complete. Leikauskas married Kusiqujluras, a sister of Javarjupankis and Tupakarančas, in 1530 as a means of symbolically claiming Cutinsuan authority for himself and for the colony of New Ruttland; the exiled Kapakrokas committed suicide less than a year after his arrival in Ruttland. While many Cutinsuan bureaucrats and vassals continued to play important roles in the administration of the region for more than half a century, by the start of 1531 the League of Five Cities had been wholly destroyed.

The last Cutinsuans

[ruttland initially coopts local kasikai and kurakai and uses them to aid their rule; resistance/unrest is scattered and crushed]

[ruttland begins to totally do away with the indigenous officials and replace them wholly with ruttish nobles and bureaucrats in the late 1590s; this leads to the 1608-1612 great cutinsuan revolt, the largest and most powerful of any neo-cutinsuan rebellions; for a time it seizes much of the highlands but it is ultimately crushed]

[in the early 1700s, during the ambiguity of the handover from ruttland to the rudolphines, there's one last attempt; but its leaders get caught and killed early, and it falls apart]

Government

[general structure of league membership - the five original cities, voluntary member cities & tributaries, conquered polities]

[administration within the five original cities]

[structures for administering the league; also legal/judicial structures]

[administration of voluntary member cities & tributaries]

[administration of conquered polities]

Society

Religion

Economy

[domestic economy]

[artifacts prove trade relations with Térachu, the Mwiska, and the Nati & Mutu peoples of the Arucian, but also with Tzapotla, Calkhun, and Itzel ]