Lecia

Lecian Workers' Republic Rzachëpòspòlëtô Robòtnika Lekkëbsczi | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Szkoda dlô jednego jest szkodom dlô kòrzdego An injury to one is an injury to all | |

| Anthem: Marsz dlô Robòtnika Lekkëbsczi (official) March of the Lecian Workers Chléb ë Mòdrôkë (popular) Bread and Cornflowers | |

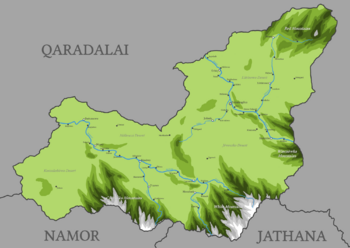

Map of Lecia | |

| Capital and largest city | Szimóngôcz |

| Official languages | Lec |

| Demonym(s) | Lec (ethnic) Lecian (citizen) |

| Government | Unitary syndicalist state; de jure directorial republic, de facto presidential republic |

| Mikòłôj Adómczyk Swiãtopôlka Dzemiónski Aleksander Jełkowski Wiktória Maszke Jùlian Mësz Miłosłôw Orlikowski Òlëwir Sërakòjski Léch Staniswônrzi Aùgust Sztroika | |

| Legislature | Workers' Assembly |

| Establishment | |

• Chiefdom | 642 |

• Kingdom | 1664 |

• Workers' Republic | 1957 |

| Area | |

• Total | 70,411.02 km2 (27,185.85 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2016 census | 5,282,690 |

• Density | 75.026/km2 (194.3/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2016 estimate |

• Total | $72.695 billion |

• Per capita | $13,761 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2016 estimate |

• Total | $67.697 billion |

• Per capita | $12,815 |

| Gini | 17.9 low |

| HDI (2015) | .705 high |

| Currency | Lecian grywna (₴) (LKG) |

| Time zone | (GMT +6:00) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | 425 |

| ISO 3166 code | LK |

| Internet TLD | .lk |

Lecia (Lec: Lekkëbë), officially the Workers' Republic of Lecia (Lec: Rzachëpòspòlëtô Robòtnika Lekkëbsczi), is a landlocked syndicalist republic in Esquarium. Located in Borea and home to roughly 5 million people, Lecia is bordered by Namor, Jathana, and Qaradalai. The country's capital and largest city is Szimóngôcz; other major cities include Ricérzów, Lùtórowo, Bónôwy, Mrzny, and Meczôszô.

Lecia is primarily inhabited by the Lec people, a Slavic ethnic group believed to have migrated from West Borea during the early common era. While traditional legends name the first Chief of the Lecs as the likely-mythical Bògùsłôw I, the first confirmed leader of a unified Lec polity was Zenón II, who assumed the title in 642. However, the power of the chieftain was severely curtailed following the Dorada War, with effective control of the country handed to a body of nobles and clergymen known as the Grand Dorada. Divisions within the Grand Dorada increasingly led to paralysis and internal conflict, and the Chiefdom collapsed following a violent civil war in 1238. During the subsequent four centuries, the country was divided between hereditary polities in Ricérzów, Bónôwy, and Mrzny, and the Archbishopric of Szimóngôcz.

After inheriting the Duchy of Mrzny in 1662, and taking advantage of turmoil within the Duchy of Ricérzów, Duke Sztefan of Bónôwy embarked on a campaign of unification that ended when he seized control of Szimóngôcz and declared himself King of Lecia in 1664. Efforts to reform the Kingdom of Lecia into a constitutional monarchy under Sztefan's descendant Krësztof I were abruptly halted following Krësztof I's probable assassination, and reversed by subsequent monarchs. These reversals, combined with poverty and public discontent, triggered a series of violent conflicts, including the Kùmiéga Rebellion in 1876, the Małinowski Revolution in 1914, and the Kãszobùski Revolution in 1957; the last of these resulted in the deposition of the monarchy and the creation of a syndicalist state. In recent decades, Lecia has been intermittently troubled by an insurgent campaign mounted by counter-revolutionary forces, known popularly as the Sorrows.

Located in eastern Borea, Lecia is known in Esquarium for its rugged, hostile terrain, which has historically helped protect Lecia from invasion by larger and more powerful neighbors. The vast majority of Lecia is considered arid or semi-arid, and the country receives little rainfall; as a result, most agricultural production occurs along the country's two main rivers, the Rzëszù and the Mòtławë, or along their tributaries; almost all of Lecia's major population centers are also located along these rivers, for similar regions. Lecia is also one of Esquarium's few landlocked countries.

Lecia is constitutionally established as a syndicalist republic, in which the government and economy are organized around a series of democratically-led labor unions. While legally a directorial republic under the Presidium of Nine, Lecia operates in practice as a presidential republic, with the president selected by the Presidium of Nine from among its own ranks. The current President of Lecia is Wiktória Maszke, who has held the position since 2016. The Presidium of Nine, in turn, is elected by the Workers' Assembly, a body composed of democratically-elected delegates primarily from the country's trade unions. These trade unions- through the Alliance of Lecian Labor Unions and the Economic Planning Committee- also serve as the backbone of Lecia's economy, which remains largely dedicated to the production of food crops such as wheat and barley, or cash crops such as cotton. Lecia does, however, have a mining sector based primarily around bauxite, and a small industrial sector dedicated primarily to textile production.

While Lecia boasts a low Gini coefficient and high HDI, and is typically democratic economically and politically, it has been criticized by foreign governments for alleged human rights violations, including the harsh suppression of ideologies deemed "counter-revolutionary". It has also been accused of attempting to suppress Rodnéwiary, the country's traditional religion, and harassing individuals who publicly practice religious rituals or holidays. Lecia's government has dismissed these allegations as unfounded, and pointed to strong workers' rights, low perceived corruption, and improved living conditions as evidence of high quality of living within the country.

Etymology

The name Lekkëbë is generally considered to have come from the Old Lec lek krae (modern Lec: lek krôjë), meaning "land of the Lec". It is speculated that the word "Lec" may derive from the Old Lec word leshe (modern Lec: lëcë), meaning "burnt", describing the harsh arid climate of Lecia; however, this etymology is not universally accepted.

History

Antiquity

The first known human population to inhabit Lecia, known as the Kléwërny culture, is believed to have arisen in the 1,100s BCE. The primary remnants of the Kléwërny culture consist of deer stones and burial sites, generally oriented along an east-west axis; while some Kléwërny culture tombs contain tools and pottery fragments, many lack these items, leading to speculation among archaeologists that the tombs were robbed by the subsequent Arénowo culture, which replaced the Kléwërny culture in the 600s BCE. The Arénowo culture produced distinctive pottery, copper and bronze tools, and stone structures that some archaeologists have described as primitive towns. Arénowo artifacts abruptly cease to appear after the 200s BCE; most archaeologists believe that some combination of drought, famine, and disease likely drove the Arénowo culture culture to extinction. Neither the Kléwërny culture nor the Arénowo culture appear to have used writing, and a lack of artifacts has made reconstruction difficult, leaving the two largely enigmatic to modern archaeologists.

After the collapse of the Arénowo culture, Lecia remained uninhabited until the arrival of the Lec people, a Slavic group of western Borean origin. Modern archaeological evidence and traditional narratives regarding the arrival of the Lecs are contradictory. Traditional religious narratives, recorded in the holy texts of Rodnéwiary, maintain that the Lecs left western Borea in 117 under the leadership of Chief Bògùsłôw I, who supposedly made a covenant with the water deity Rzékobòg that the Lecs would worship him alone in exchange for being led to the region, and that the Lecs arrived in 219. The polity established by Bògùsłôw I- known as the First Chiefdom of the Lecs- supposedly continued to exist until it was destroyed by Rzékobòg in 488, as punishment following a string of sinful rulers.

Modern archaeological evidence, however, suggests that the Lecs did not arrive until the 400s CE, and that Rodnéwiary did not become monotheistic until after the arrival of the Lecs in the region; archaeologists regard the traditional narrative to be little more than a national myth, and consider Bògùsłôw I, his successors, and the First Chiefdom of the Lecs to be mythical. At the same time, it is clear that historical rulers of Lecia regarded the First Chiefdom as a real, historical polity; when Zenón Zenónsczi proclaimed himself Chief of the Lecs, he styled himself as Zenón II, as there had supposedly been a previous Chief Zenón during the First Chiefdom, and many subsequent Lec noble houses claimed descent from the Bògùsłôwsczi clan.

Second Chiefdom

By the 500s CE, power within Lecia was divided between several clans, including the Zenónsczi, Czlëchòwsczi, Krzénsczi, Sùlëcczi, Bartôszczi, and Kyrzëcsczi. Through a mixture of diplomacy, vassalization, and conquest, these clans were unified into the Second Chiefdom of the Lecs, the first historically-confirmed Lec polity, by Zenón II- a member of the Zenónsczi clan- in 642. Following his ascension, Zenón II solidified his power by forming a body of advisers drawn from a handful of other major clans, with the aim of guaranteeing their support for his regime. Zenón II also worked to obtain the favor of Rodnéwiary clergy primarily by offering financial support to Rodnéwiary churches and orders.

In 698, Zenón II's grandson Tëmon IV claimed to have received a divine sign calling for the replacement of the Council of the Holy- at the time the final religious authority within Rodnéwiary- with a single religious leader. After obtaining the backing of his advisors, and supposedly proving the veracity of the sign to the Council of the Holy, Tëmon IV opted to name the head of the Szimóngôcz Monastery to the title of sëlnoswôszénik- commonly translated as "archbishop"- instead of one of the individuals on the council. While this provoked controversy, Tëmon IV forced the Council of the Holy to acquiesce, and Bòlesłôw I was recognized as the first Archbishop of Szimóngôcz. The relationship between Tëmon IV and Bòlesłôw I was preserved as close ties between the Lec monarchy and Rodnéwiary clergy, to the benefit of both institutions, in subsequent centuries.

Zenónsczi rule over Lecia ended abruptly in 763 with the disappearance of Sùlisłôw II, likely at the hands of his regent and uncle-by-marriage Nôrcyz, who declared himself Nôrcyz I following his nephew's disappearance. While initially met with hostility from both other nobles and the clergy, Nôrcyz I successfully bribed or threatened the other clans into supporting him and installed an ally as Archbishop Iszydòr II, silencing overt opposition among the clergy. Nôrcyz I's descendants proceeded to rule Lecia for the following 200 years, excluding a brief interruption during the War of the Usurpation, when the chiefdom was briefly seized by a member of the Czlëchòwsczi clan. The Nôrcyzsczi clan went extinct in 972, with the death of the infertile Chief Bòlesłôw I; Bòlesłôw's council named Tëmon V, a member of the Krzénsczi clan, as the new Chief of the Lecs.

Lecia remained at peace until the beginning of the Dorada War, conducted against Chief Zenón VI, in 1001. Described as indecisive, reclusive, and apathetic, Zenón VI's poor rule resulted in widespread opposition among other clan leaders and within the clergy; after a botched attempt by Zenón VI to jail several of his opponents, open conflict ensued. The conflict ended in 1008; in exchange for retaining his title, Zenón VI agreed to cede most of his powers to a council consisting of representatives from prominent noble families and the clergy. This body, known as the Grand Dorada, became the center of power in Lecia for the remainder of the Second Chiefdom's existence.

As time passed, the Grand Dorada became steadily more and more powerful, and the chief increasingly became a figurehead. The forced abdication of Bògùsłôw V in favor of his brother Macéj established that the Grand Dorada had the authority to force a chief's abdication; the violent overthrow of Tëmon VII, which ended the rule of the Krzénsczi clan, established that it had the authority to depose the ruling chief. The ensuing instability, combined with the periodic devolution of the Grand Dorada into factional paralysis, resulted in a weakening of central authority and a steady national decline.

In 1231, the Grand Dorada voted to depose Zenón VII Bartôszczi and replace him with Łukôsz Perszysczki, but the vote was contentious and many in the body opposed it vehemently. Bolstered by this support, Zenón VII refused to concede the title and the War of Thorns ensued. During the ensuing conflict, the Grand Dorada split into two separate bodies, one recognizing Zenón VII and the other recognizing Łukôsz. During the conflict, both Zenón VII and Łukôsz died, being succeeded by Miłosłôw and Tëmon VIII, respectively. The Battle of Jigrowò in 1238 saw the deaths of both Miłosłôw and Tëmon VIII, as well as several of their major supporters and a majority of their armies. Shortly following the battle, Archbishop Mikòłôj V claimed that the battle was a sign that Rzékobòg had willed the destruction of the chiefdom; the remnants of the warring parties, devastated following years of conflict, ultimately acquiesced to this notion, ending the existence of the Second Chiefdom.

Four States Period

The collapse of the Second Chiefdom of the Lecs led to a power vacuum in Lecia that was filled by four smaller, regional polities: the Duchy of Ricérzów under the remnants of the Perszysczki clan, the Duchy of Bónôwy under the Vejlewszczi clan, the Duchy of Mrzny under the Wyrowinski clan, and the Archbishopric of Szimóngôcz. This division, which remained effectively unaltered until the 1600s, has resulted in the period being widely known as the Four States Period.

As a result of the division, Lecia was periodically wracked by conflict between the four polities. Nevertheless, Lecian culture continued to develop, in part because of patronage from rulers and leading nobles. The Church of Rodnéwiary in particular became the leading patron of artistry during this period. Among the artists who benefited from such patronage included painter Tëmon Sztalowski, sculptor Roman Òbłonski, and playwright Matéùsz Gòdniéski. Patronage from the church also increased the stature of Szimóngôcz, the seat of religious authority, in relation to the traditional secular capital of Bónôwy. Increasing contact with nearby Monic nations during this period led to cultural exchange between the two groups, and the development of trade routes that followed the courses of the Rzëszù and Mòtławë through Lecia; this brought wealth to the region, which further enabled patronage of the arts.

The remainder of the 1200s proved largely peaceful, as the various successor states attempted to recover from the devastation of the War of Thorns and cement their own power. Peace between the polities was also bolstered by the 1251 Edict of Recognition, issued by Archbishop Mikòłôj V, which formally recognized Bónôwy, Mrzny, Ricérzów, and Szimóngôcz as the successors to the Second Chiefdom of the Lecs. The first major conflict between any of the polities, the Mrzny-Bónôwy War, began in 1317 and ended inconclusively in 1320. It was followed by the War of the Wheatfields, in which Archbishop Cërël III of Szimóngôcz and Duke Môrcën II of Bónôwy declared an alliance to depose the Perszysczki rulers of Ricérzów, who had been agitating for the restoration of the chiefdom under their leadership. The war was a victory for Szimóngôcz and Bónôwy, who installed Tëmon IV Łiakòwski as Duke of Ricérzów.

Bónôwy's own House of Vejlewszczi went extinct in 1420, and the throne was passed to the related House of Miastkòwski; however, in 1471, the long-reigning and widely-respected Duchess Jùlja died without heir. The nobles of the polity ultimately agreed to pass the title to Feliks Wiszniewski, who was installed as Duke Feliks I shortly thereafter. The 1400s also saw periodic instability and political violence in Ricérzów, manifesting in the assassination or attempted assassination of four Dukes of Ricérzów during the century, and a failed attempt by Archbishop Bògùsłôw VIII to diplomatically establish a unified Lecian state under the Rodnéwiary church.

Szimóngôcz did successfully exercise secular political power in 1538, however, by successfully orchestrating the deposition of Duke Teodór V of Mrzny and installation of his half-brother Mieczysłôw as duke, in spite of opposition from the Duchy of Bónôwy. Political instability and violence in Ricérzów, fostered by Szimóngôcz and Bónôwy, worsened substantially during the 1500s, manifesting in the failed 1549 Plaszkëwski coup and the extinction of the House of Łiakòwski in 1577. These conflicts also created deep animosity between Szimóngôcz and Bónôwy, as they increasingly competed to become the dominant polity within Lecia. The 1624 Treaty of Reconciliation, signed by Jerzy III of Bónôwy and Archbishop Bògùsłôw IX aimed to repair the acrimonious relationship between the two; in spite of the treaty, however, both polities continued to manipulate the politics of Mrzny and Ricérzów in secret.

Open hostilities resumed in 1658, when Duke Sztefan II of Bónôwy inherited the Duchy of Mrzny from Môrcën IV, triggering a chain of events now known as the Òdroda, or "revival". Fearing this would disrupt the balance of power, Archbishop Bòlesłôw XIII attempted to trigger a rebellion in Mrzny; the rebellion failed to materialize, however. In 1661, a bread riot in Ricérzów resulted in the flight of Duke Krësztof II from the city. While Krësztof II attempted to organize a response, Sztefan II and his army marched north, seizing Ricérzów and bringing with them large amounts of wheat and barley. Desperate to curtail Sztefan II's power, Bòlesłôw XIII excommunicated him and declared war. The war went poorly for Szimóngôcz, however, and in 1664 Bónôwy's armies captured Szimóngôcz itself; shortly thereafter, Sztefan II declared himself to be the first King of Lecia.

Kingdom of Lecia

Having established himself as King Sztefan of Lecia, Sztefan quickly moved to guarantee the supremacy of his new government over the nation and the church. He forced Bòlesłôw XIII to lift his excommunication, and to abdicate the position of archbishop and retire to a monastery; Sztefan then guaranteed the election of his brother Feliks as Archbishop Cërël VIII. He also moved his capital from Bónôwy to Szimóngôcz, symbolically claiming the city as a sign of his power over the church. He courted the favor of nobles and awarded titles and lands to supporters, making him popular among the nobility; he also lowered tax burdens on the peasantry at the expense of the church, which made him popular among the commoners and earned him the appellation Ukòchani, or "the Beloved". He died in 1702, widely respected by both nobles and commoners as a strong and just king.

Sztefan's heir, Kôrol I, proved to be a less capable ruler than his father, antagonizing many of Sztefan's allies; these relationships, however, were salvaged by his successor, King Jerzy I. Jerzy I also worked to reconcile the crown's relationship with the clergy, signing the Pact of Perpetual Amity with Bògùsłôw X in 1745. Bolstered by peace and stability under Jerzy I and his immediate successors, Lec culture flowered; famous artists from the era include painters Oskar Błasiewicz and Jaroszcłôw Polkowski, author Frãcëszk Krajnôski, and composer Wincénty Tomôszki. In spite of this general prosperity, however, issues began to arise. Republican ideals, which called into question Lecia's absolute monarchy, gained traction in some intellectual circles, and the failure of wages to keep up with prices created widespread frustration among the general public.

In an attempt to address this discontent, King Krësztof I promulgated a series of broad-ranging reforms that included abolishing serfdom, writing a constitution, creating an elected Royal Congress, implementing price controls on certain foodstuffs, and increasing the tax burden on the nobility and clergy. These reforms were wildly popular among commoners, who lauded him as "the People's King", but they antagonized many nobles and clergymen, and many historians suspect that Krësztof I's death by strychnine poisoning in 1842 was engineered by nobles hostile to his efforts.

After Krësztof I's death, these nobles took advantage of Paweł I's weak rule to lower taxes on the nobility, overturn the Constitution of 1828, and abolish the Royal Congress. Paweł I died without an heir only five years later, however, and the nobility opted to name Krësztof II Òłówski as his successor. Krësztof II attempted to balance the demands of the nobility with the demands of the commoners; he wrote a new constitution and re-instituted the Royal Congress, but he also added property requirements for suffrage as a concession to nobles and refused to raise taxes on nobles and the clergy as Krësztof I had. Efforts at reform were thwarted once again, however, by Krësztof II's son Jerzy II, who suspended the constitution and revoked the Royal Congress's legislative authority in 1875.

These reversals provoked nationwide unrest, which spiraled into outright violence in 1876 with the outbreak of the Kùmiéga Rebellion, in which a broad coalition of pro-reform factions led by composer and playwright Andrzéj Kùmiéga attempted to establish a republican government in Lecia. The rebellion was crushed in 1879, but public anger about stagnant wages, rising prices, and reactionary politics persisted, and led to the First Lecian Revolution in 1914, during the rule of Jerzy II's son Mikòłôj. This revolt, spearheaded by communist forces under Jigór Małinowski, lasted until Małinowski's capture and execution in 1918; once again, however, the Kingdom of Lecia failed to address public discontent, which again turned violent with the Second Lecian Revolution in 1957. Led by Szimón Kãszobùski and claiming succession to Małinowski's revolution, these revolutionaries declared the foundation of a "workers' republic" in Lecia, and successfully forced the monarchy and clergy into exile in 1959.

Workers' Republic

Following the flight of the Lecian monarchy, the leaders of the Second Lecian Revolution moved quickly to establish a syndicalist state in Lecia, loosely based on the communist state proposed by Małinowski during his failed insurrection. The ensuing state was based around a Workers' Assembly containing representatives from various labor unions and, in theory, a Presidium of Nine that would function as a joint executive. In practice, however, Kãszobùski was able to establish himself as the de facto President of Lecia, and the Presidium of Nine was relegated to functioning as a cabinet. The new state moved quickly to extend protection for workers, implement universal suffrage, and improve living conditions; however, it also moved to suppress elements deemed counter-revolutionary through the usage of the army and the secret police.

The emphasis of the new regime on living conditions and workers' rights did result in drastically-improved living conditions across Lecia during the Kãszobùski presidency. Kãszobùski retired in 1971, and was succeeded by Józef Kasperski; while initially focused on further improving economic conditions, the 1974 formation of the Lecian Resistance Army- a coalition of militant groups opposed to the Lecian government- forced him to focus on security issues. The conflict between the Lecian government and the Resistance Army- widely known as the Sorrows- intensified in the 1980s under President Irenéùsz Cybulski, who vowed to destroy the group if elected, and his successor Mikòłôj Adómczyk. The 1981 foundation of the Solidarity Alliance by Lecian exiles stoked further conflict; the Lecian government labelled the group a front for anti-government militants, in spite of Solidarity's insistence it sought a peaceful return to democracy in Lecia. Some limited rapprochement took place under Janusz Mëdzerz, but ended abruptly with Mëdzerz's death in 2008. The current President of Lecia, Wiktória Maszke, was elected in 2016.

Politics

Governance

Lecia is constitutionally established as a directorial republic, with joint executive power held by a body known as the Presidium of Nine, whose membership is to be elected by the country's legislature following a general election, or as needed in case of an unexpected vacancy. In practice, however, Lecia operates under a presidential system, with the President of Lecia- selected by and from the Presidium- serving as the head of state, head of government, and commander-in-chief of the armed forces; the Presidium of Nine, meanwhile, functions as a cabinet. The current members of the Presidium of Nine are Mikòłôj Adómczyk, Minister of Foreign Affairs; Swiãtopôlka Dzemiónski, Minister of Finance; Aleksander Jełkowski, Minister of Labor; Wiktória Maszke, Minister of Domestic Affairs and the incumbent President of Lecia; Jùlian Mësz, Minister of Health, Welfare, & Sport; Miłosłôw Orlikowski, Minister of Defense; Òłëwir Sërakòjski, Minister of Justice; Aùgust Sztroika, Minister of the Environment & Transport; and Léch Staniswônrzi, Minister of Education & Science.

The legislature of Lecia, known as the Workers' Assembly, is composed of 285 elected delegates from various organizations. The majority of these delegates are elected by the eleven unions belonging to the Alliance of Lecian Labor Unions; however, organizations such as the Democratic Women’s League of Lecia, Young Revolutionaries, and Workers’ Army of Lecia also send delegates to the Workers' Assembly. In addition, fifty seats are elected from geographic constituencies using party-list proportional representation. To run candidates, parties must be recognized and approved by the Lecian government; at present, five parties- the Lecian Syndicalist Party, Union of the Revolutionary Proletariat, Revolutionary Socialist Front, Lecian Anarchist Federation, and Free Laborers' Party- are recognized. These parties, in turn, are all members of a coalition known as the National Revolutionary Camp. Elections are held every three years. The presiding officer of the Workers' Assembly is known as the Speaker, and is in charge of managing the proceedings of the body.

Lecia currently uses a civil law system based on socialist legal systems in Austrosia and Alemannia, and to a lesser extent on early republican systems from Aucuria and Ainin. Trials follow the inquisitorial system, in which judges can actively participate in fact-gathering; however, final rulings are made by a jury. Civil disputes and minor criminal charges are heard by courts known as district tribunals; appeals of decisions by district tribunals are heard by courts of appeal, while severe criminal offences are handled by provincial tribunals. Appeals from provincial tribunals and courts of appeal are in turn heard by national tribunals, then by the Constitutional Court in civil and administrative cases or the Court of Cassation in criminal cases.

While Lecia's political system is broadly democratic and free from rigging and corruption, and the country's constitution formally guarantees freedom of thought, speech, and the press, human rights concerns about Lecia's political system persist. Organizations and parties that diverge too far from approved lines of political thought risk losing recognition or being shut down, and "counter-revolutionary actions" remain a crime under Lecian law. Human rights organizations also allege that individuals who express "counter-revolutionary" opinions become second-class citizens and lose many of their rights, including the right to vote. The government of Lecia has rejected these allegations as unfounded, insisting that it only acts to preserve the stability of Lecia and the freedom of its people.

Administrative divisions

Lecia is divided into 12 provinces (Lec: wòjewództwa, sing. wòjewództwò), which are in turn subdivided into 54 districts (Lec: krézë, sing. kréz). As Lecia is a unitary state, its provinces hold little autonomy; while provinces are accorded some limited authority over public services, local roads, and sanitation, and have a limited ability to levy taxes, decisions made by provincial governments can easily be overturned by the national government. Provincial and district officials are typically elected every three years.

| Map | Name | Capital | Population | Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bnëcznowo | Bnëcznowo | tbd | tbd km² | |

| Bónôwy | Bónôwy | tbd | tbd km² | |

| Brzny | Brzny | tbd | tbd km² | |

| Jelénik | Jelénik | tbd | tbd km² | |

| Lãczëce | Lãczëce | tbd | tbd km² | |

| Lùtórowo | Lùtórowo | tbd | tbd km² | |

| Meczôszô | Meczôszô | tbd | tbd km² | |

| Mrzny | Mrzny | tbd | tbd km² | |

| Przawo | Przawo | tbd | tbd km² | |

| Ricérzów | Ricérzów | tbd | tbd km² | |

| Szimóngôcz | Szimóngôcz | tbd | tbd km² | |

| Ùchòj | Ùchòj | tbd | tbd km² |

Largest cities

Largest cities or towns in Lecia

2010 census | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Province | Pop. | Rank | Province | Pop. | ||||

Szimóngôcz  Bónôwy |

1 | Szimóngôcz | Szimóngôcz | tbd | 11 | Brzny | Brzny | tbd |  Ricérzów  Mrzny |

| 2 | Bónôwy | Bónôwy | tbd | 12 | Lãczëce | Lãczëce | tbd | ||

| 3 | Ricérzów | Ricérzów | tbd | 13 | Górno Dzlasziô | Szimóngôcz | tbd | ||

| 4 | Mrzny | Mrzny | tbd | 14 | Leszczëna | Mrzny | tbd | ||

| 5 | Bnëcznowo | Bnëcznowo | tbd | 15 | Òłówo | Bónôwy | tbd | ||

| 6 | Lùtórowo | Lùtórowo | tbd | 16 | Mółiwies | Ùchòj | tbd | ||

| 7 | Meczôszô | Meczôszô | tbd | 17 | Rzëszùwies | Ricérzów | tbd | ||

| 8 | Jelénik | Jelénik | tbd | 18 | Wejròwo | Bnëcznowo | tbd | ||

| 9 | Przawo | Przawo | tbd | 19 | Hãjbatë | Lùtórowo | tbd | ||

| 10 | Ùchòj | Ùchòj | tbd | 20 | Niékowo | Szimóngôcz | tbd | ||

Foreign relations

Lecia has warm relations with other traditionally leftist states such as Austrosia, Alemannia, and Namor. Namor in particular has become an important trading partner and strategic ally to Lecia, as one of the few nearby states that is friendly to Lecia; a significant portion of Lecia's imports enter the country through Namor. Lecia's relations with Namor's political partners, such as the Union of Nautasian Islamic Republics, Razaria, Jathana, and Xiaodong, are cordial in spite of ideological differences. Relations between Lecia and liberal democratic states, and organizations such as the Esquarian Community, are typically cool, though there have been periodic escalations of tensions, due either to Lecian ideological hostility towards such states or to foreign concerns regarding human rights within Lecia.

Relations between Lecia and nations that it deems "openly counterrevolutionary"- including Ambrose, Akai, and Tuthina- are cold or outright hostile, though Lecia's distance from these countries means little of consequence results from these tensions. Lecia's warm relations with Namor also mean that it has historically been hostile towards Luziyca. In addition, Lecia has mixed relations with its neighbor Qaradalai, which accuses Lecia of funding and sheltering ethnic Lec militant groups active in Qaradalai's restive western regions; the Lecian government has denied these claims, but does say it "supports the right of Lecs in Qaradalai to self-determination and, should they choose it, independence or annexation into Lecia".

Lecia is a member of the International League, and was a member of the Organization of Esquarian Nations before its dissolution. Lecia is also a member of the International Forum for Developing States.

Military and police

Lecia's military is known as the Workers' Army of Lecia. There is no separate air force; instead, the army operates an aerial warfare service within the army, known as the Workers' Air Corps. Lecia also has an army reserve, known as the National Militia. The minimum legal age for voluntary admission to the army or the militia has been 18 since 1969. There are legal provisions for a draft lottery for all citizens between 18 and 24 for a two-year tour of duty, with an alternative service option for conscientious objectors; since 2004, however, conscription is currently not in effect and the Workers' Army operates as a volunteer force. The army has thirty-five seats within the Workers' Assembly.

Lecia's national police force and primary law enforcement agency is the National Police, which conducts security operations, manages criminal investigations, and oversees services such as traffic control as necessary. Subsections of the National Police include the Bureau of Customs and Border Protection, which enforces customs and immigration law, and the National Security Service, which protects prominent government officials within Lecia and abroad. The sole intelligence agency in Lecia is the National Security Agency, which handles domestic intelligence, foreign intelligence, and counter-intelligence operations for the Lecian government.

Geography

Lecia is a landlocked country located in the continent of Borea, bordered to the south by Namor and Jathana and to the north by Qaradalai. It lies between the latitudes of 30° and 34° N, and the longitudes of 61° and 65° E.

Lecia's terrain is rugged and inhospitable, dominated primarily by mountains and deserts. Major mountain ranges include the Red Mountains (Góry Czerwòny), Czëpnéka Mountains (Czëpnéky), White Mountains (Góry Biôłi), and Wieczòwka Mountains (Wieczòwki). The White Mountains form the highest mountain group in Lecia; the country's highest peak- Mount Klëczka, with an elevation of 4,871 meters- is located within the White Mountains. Major deserts include the Lùtórowo Desert (Pùsztéljô Lùtórowa) in the north, the Môłiesczi Desert (Pùsztéljô Môłieska) and Jéweszko Desert (Pùsztéljô Jéweszka) in the country's center, and the Kretszkebòwo Desert (Pùsztéljô Kretszkebòwa) in the south. This rough terrain has historically served as a protection against potential invasion by larger neighbors; however, it also means that very little of Lecia's land area is arable.

As a result of this inhospitable terrain, Lecia's arable land and population are clustered around the country's river valleys. These include the valleys of Lecia's largest rivers, the Rzëszù and the Mòtławë, and their tributaries, including the Dzlasziô, Saléra, Łëpawa, and Prósna. The overwhelming majority of Lecia's cultivated land, forested land, and major population centers are clustered along these rivers and tributaries, which also serve as the primary source of water in Lecia's rain-starved climate. Almost all of Lecia is within the drainage basins of either the Mòtławë or the Rzëszù, both of which ultimately flow into the Central Ocean.

| Szimóngôcz, Lecia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Climate

Under the Köppen classification system, the majority of Lecia has a cold desert climate (BWk), with hot summers, cold winters, and less than 200 millimeters of rain annually; however, some areas on the country's western borders are classified as cold semi-arid (BSk), which experience similar temperatures but higher rainfall. In general, winter temperatures in Lecia typically average about 6 °C (43 °F), whereas summer temperatures usually rise above 30 °C (86 °F). Almost all of Lecia sees less than 250 millimeters of precipitation per year, and there is little air humidity; most precipitation falls between December and March, periodically in the form of snow.

Wildlife

Most of Lecia is considered to be desert or xeric shrubland by biologists, though riparian zones exist along the valleys of Lecia's major rivers, and some particularly high areas within Lecia's mountain ranges are intermittently classified as alpine tundra. Lecia's generally dry and hostile conditions have resulted in a widespread presence of xerophytic flora, such as creosote, sagebrush, cacti, and Esparto grass; such plants, which have adapted to Lecia's harsh desert conditions, form the majority of Lecia's relatively sparse vegetation. Other plants native to Lecia include quinces, irises, apricots, and mariposas.

Similarly, many animals living in Lecia are either xerocoles or adapted for mountainous habitats. Nevertheless, Lecia boasts a diverse range of fauna, including many species of reptiles, birds, and mammals. Reptile species native to Lecia include the diadem snake, Lec cobra, spotted whip snake, and western banded gecko; avian species include the Jéweszko woodpecker, cream-colored courser, steppe eagle, burrowing owl, and cinereous vulture; mammalian species include the jerboa, Lecian wolf, caracal, urial, Xhipei camel, and desert cottontail.

As of 2010, there are 112 protected animal species and 241 protected plant species within Lecia. Efforts to protect these species have been redoubled in recent years due to the comparative fragility of Lecia's desert ecosystems, which are highly sensitive to disturbance or disruption. Lecia has nine national parks, twenty-four nature reserves, and fourteen natural monuments.

Economy

Lecia's economy is organized in a syndicalist fashion, in which all sectors of the economy are organized into labor unions with democratically-elected leadership. The Lecian economy is divided between eleven unions: Artists and Athletes, Builders and Engineers, Bureaucrats and Lawyers, Commercial and Hospitality Workers, Farmers and Ranchers, Financial Workers, Miners and Loggers, Police, Teachers, Doctors, and Scientists, Telecommunications and Infrastructure Workers, and Textile and Industrial Workers. All eleven are members of the Alliance of Lecian Labor Unions, a national federation of unions that wields significant power within the Lecian government and society, in part because laborers are legally obligated to join the union pertaining to their profession.

Delegates elected by the membership of these unions form the majority of the Workers' Assembly, holding almost sixty percent of the seats in the body. In addition to sending delegates to the Workers' Assembly, the member unions of the Alliance of Lecian Labor Unions also send representatives to a body known as the Economic Planning Committee, whose duties include drafting plans for economic development, compiling economic statistics, ensuring resource allocation, monitoring production, promoting industriousness among workers, verifying the enforcement of labor laws and regulations, and reporting the state of Lecia's economy to the Workers' Assembly and the Alliance of Lecian Labor Unions.

The focus of the Lecian government on labor rights has resulted in drastically improved for Lecian workers. Lecia has strict laws regarding workplace safety, a well-enforced living minimum wage, parental leave for both mothers and fathers, stringent regulations against child labor and unfair dismissal, and laws limiting the length of the workday and guaranteeing paid vacation; widespread workplace democracy and protections for collective bargaining, meanwhile, helps to guarantee accountability and maintain good working conditions.

Agriculture

Agriculture, organized around cooperative farms and overseen by the Union of Farmers and Ranchers, is the largest sector of the Lecian economy. Most Lecian agriculture remains dedicated to food crops, particularly staple crops such as wheat, barley, and potato. Other major food crops include chickpeas, spinach, onions, dates, and figs. Smaller segments of Lecian agriculture are dedicated towards cash crops, primarily cotton, and to fodder crops for animals, such as clover. Animal husbandry is also a notable portion of Lecia's agricultural sector and, like the production of food and cash crops, is collectivized. Animals commonly raised in Lecia include chickens, sheep, goats, and camels; chief livestock products include meat, dairy products, wool, and leather.

Lecia's dry climate and sparse precipitation strictly limits where agriculture is viable, trapping it within the valleys around rivers such as the Rzëszù, Mòtławë, Dzlasziô, and Łëpawa, and making it largely dependent on irrigation. In the past, some Lecian politicians proposed attempting large-scale irrigation projects aimed at turning large areas of Lecia's desert into arable land; however, these proposals never gained more than a fringe following, and were invariably dismissed as risky and overly expensive.

In recent years, as Lecia's population and agricultural sector have grown in scale, concerns about these rivers being overused- and the ensuing impacts on the environment, the public, and countries downstream such as Qaradalai and Namor- have been raised. In response to these concerns, the Lecian government has put substantial amounts on money into refurbishing aqueducts to prevent leakage and evaporation, created guidelines on how often certain crops should be watered, encouraged local governments to implement laws regarding municipal and individual water use, and created a strict water-rationing program should the measured outflow of the Rzëszù or Mòtławë at Lecia's western border dip below certain values.

Mining

Lecia's mining sector is overseen by the Union of Miners and Loggers, and is focused primarily around the extraction of bauxite and other aluminum ores. In addition to being used in domestic heavy industry, bauxite composes 62.7% of Lecia's mineral exports as of 2015. Other resources mined in Lecia include limestone, zinc, and natron. Historically, Lecia was also a source of niter, used in the manufacture of gunpowder and fertilizers, for much of eastern Borea; however, the invention of smokeless powder and synthetically-produced nitrates resulted in the end of Lecia's niter-mining sector.

In spite of the name of the Union of Miners and Loggers, the timber-production sector in Lecia is effectively nonexistent as only 4% of Lecia is classified as "forested". The union was renamed from the "Union of Miners" to the "Union of Miners and Loggers" in 1972, amidst an abortive plan to develop a forestry sector in Lecia by planting groves of trees in the Rzëszù river valley; the plan was abandoned in 1975 due to cost, however, and in the modern era Lecia typically imports wood from Namor.

Industry

Lecia has a comparatively small industrial sector, consisting primarily of consumer-oriented light industry, in particular textile manufacturing and food processing. Heavy industry composes a far smaller segment of Lecian industry, and is primarily dedicated to the smelting and refining of aluminum and zinc. Lecian industry, regardless of whether light or heavy industry, is overseen by the Union of Textile and Industrial Workers.

The development of these particular industries has been encouraged by successive Lecian governments as they rely on products that can be produced domestically by Lecia's agricultural or mineral sectors; however, in recent years, the growth of Lecian industry- particularly textile manufacturing- has required the importation of raw materials from abroad.

Commerce and finance

Commerce, which is overseen by the Union of Commercial and Hospitality Workers, forms a comparatively small part of the Lecian economy. While the Lecian government has attempted to incentivize and encourage trading with other far-leftist states, such as Alemannia, Lecia's distance from these states has limited trade severely. In practice, a significant portion of Lecia's trading is with nearby Monic nations simply due to geographic convenience.

Lecia's financial sector is overseen by the Union of Financial Workers, and is only a small part of the Lecian economy. The country has one bank, the state-run National Bank of Lecia, which functions both as a central bank and as a retail bank; however, there are also has a handful of collectively-owned credit unions in Lecia that provide services similar to that of a retail bank. Insurance is also handled by a state-owned company, the People's Insurance Company.

Media

Media in Lecia is overseen by the Union of Telecommunications and Infrastructure Workers; all newspapers, magazines, radio stations, and television stations are required to be licensed by the ÙRPTI. National newspapers within Lecia include Prôwdze Robòtnika, Czãdnik Wòjskowy, Płômien Czerwòny, and Szpòrt Lekkëbi; the news magazine Lekkëbë Tidzéniowi also circulates nationally. Local newspapers and news magazines in Lecia include Czãdnik Szimóngôczi, Gazeta Ricérzówska, Czãdnik Bónôwa, Mrzny Dzysô, Prôcownik Meczôszka, and Czãdnik Wòlny Brzny. Radëjotelewizëjô Robòti Lekkëbsczi serves as the country's primary radio and television broadcaster.

While the Constitution of Lecia formally guarantees freedom of speech and of the press, media freedom remains tightly restricted; Lecian media is censored to remove "counter-revolutionary sentiments", and laws criminalizing "counter-revolutionary actions" have been used to jail journalists critical of the government or expel them from their positions. As a result, Lecia often scores poorly on press freedom indexes. In an attempt to counter the Lecian government's control on the media, dissident newspapers published outside of Lecia- such as Samòstójnocczi, Trzëfarwa, and Twierdza- have been smuggled into the country by opposition groups, and broadcasting organizations such as Słunice Lekkëbi have attempted to broadcast into Lecia, though they face radio jamming by the Lecian government, which considers them "subversive".

Infrastructure

Transportation

Most of Lecia's land transportation infrastructure is located within the country's river valleys. Lecia has five national controlled-access motorways, four of which follow a major river for part of their route, and only two of which cross the deserts between the Rzëszù and Mòtławë river valleys. Smaller roads are maintained jointly by the national government, local governments, and the Union of Telecommunications and Infrastructure Workers. Lecia has a small rail network, managed by Lecian People's Railways.

While transport by water has historically been important within Lecia, particularly for international trade, instability in western regions of Qaradalai has periodically disrupted trade along the Rzëszù and Mòtławë rivers, as have tensions in the Gulf of Gelyevich, which both rivers ultimately flow into. There are three international airports within Lecia, located in Szimóngôcz, Ricérzów, and Bónôwy. Lecia's flag carrier is Air Lecia.

Telecommunications

Lecia constructed large amounts of telecommunications infrastructure for usage by Radëjotelewizëjô Robòti Lekkëbsczi and Lecian Telecom in the 1970s, alongside a similar transportation infrastructure push requested by labor delegates from Pòczta Lekkëbi and other workers within the ÙRPTI. A similar effort was made in the late 1990s and 2000s to increase Lecian access to telephone service and the Internet, particularly in rural areas.

Energy

Due to a near-total lack of domestic energy sources, Lecia imports the overwhelming majority- more than 70%- of the fuel it uses for electricity production. The overwhelming majority of these imported fuel sources, in turn, are fossil fuels, particularly oil and natural gas; these fossil fuels continue to form the backbone of Lecian energy production.

This dependence on imported fuel and the associated environmental concerns have prompted intense discussion regarding the adoption of renewable energy sources within Lecia. Beginning in the early 1980s, some Lecian scientists and politicians began proposing the construction of hydroelectric dams along the Rzëszù and Mòtławë rivers. However, there were concerns that construction of such dams could prove too expensive, that valuable arable land might be submerged by the subsequent reservoirs behind the dams, and that the dams could become targets for terrorist groups amidst the Sorrows; these concerns ultimately led to the rejection of said hydroelectric proposals.

In the past 20 years, there has also been intense discussion regarding the adoption of solar power, as much of Lecia has a high solar irradiance value. While concerns regarding cost were also raised in regards to solar power, the Workers' Assembly approved a resolution calling for the adoption of solar power in 2007; since then, solar power has become the source of as much as 15% of Lecia's electricity. In recent years, there have been even more ambitious proposals to construct vast solar farms in the Lecian desert, turning unproductive land into a major source of power; the government of Andrzéj Sikora drafted plans in 2015 to construct five such solar farms by 2025; as of 2017, however, none of these plants are online.

Tourism

Tourism comprises a very small sector of the Lecian economy. While there was limited discussion regarding Lecia's tourist sectors during the 1980s, the escalation of the Sorrows and the ensuing negative press effectively silenced all discussion of Lecia as a potential tourist site for several decades. With the deescalation of the Sorrows in the early 2000s, however, there has once again been discussion of expanding Lecia's tourism sector. The government of Wiktória Maszke formally announced a campaign to promote ecotourism in Lecia by renovating several of Lecia's national parks and promoting them abroad as ecotourist destinations.

Public policy

As a syndicalist state, Lecia has abolished private property and private business; as a result the state is unable to fund itself through property taxes. In place of this, Lecia's government is funded primarily by income and value added taxes, and to a lesser extent on tariffs placed on certain goods deemed "critical for domestic use" by the Lecian government. Lecia formally utilizes a progressive tax system, in which an individual's tax rate increases as the taxable amount increases; however, Lecia has low wealth inequality and a relatively narrow income distribution, and government data from 2014 suggested that no individuals actually fell within the country's top two tax brackets during the previous year.

Lecia has a substantial welfare system, which the government maintains "is an important part of guaranteeing equality and social mobility within Lecia". The country's welfare system operates using a Ghent system in which labor unions handle unemployment benefits and pension payments, while the government alone handles homeless shelters, poverty assistance programs, and food supplement programs. This arrangement has come under criticism from some groups, who maintain it is more complex than simply leaving all welfare services to the government, or that it unfairly shunts the financial burden onto unions; however, proponents of the arrangement maintain that the system is in line with Lecia's syndicalist method of government.

Demographics

With a population of 5,282,690 people and a population density of only 75 people per square kilometer, Lecia is one of Borea's smallest and least dense countries. Due to advancements in agricultural technology and pro-natalist policies, Lecia's population is comparatively young, with 33.8% of the Lecian population being below the age of 15. The country's total fertility rate is 2.6; the average life expectancy in Lecia is 70.5 years.

There exists a small Lecian diaspora, consisting of about 2.3 million people. The vast majority of this diaspora- roughly 1.6 million people- resides in Qaradalai, primarily within the region of Sekhessia. Smaller portions, consisting mostly of the descendants of refugees or of political exiles, are scattered elsewhere throughout Esquarium, with Lec exile communities existing in Luziyca, Ainin, and Sjealand.

Ethnicity

The Lec people are the primary ethnic group in Lecia and by far the most numerous ethnic group within the country, composing roughly 98% of the population as of the country's 2010 census. The Lecs are a Slavic ethnic group of West Borean origin, believed by scholars to be most closely related to groups such as the Ceresnians and Sloviacs. A 2011 analysis of Y-chromosome and MtDNA haplogroups found that the most common haplogroups among the Lecian people are R1a and J1b, respectively.

Of the remainder of the Lecian population, approximately 1.5% is classified by the Lecian government as "Transborean". Historically, Transboreans in Lecia were found primarily in regions of the Rzëszù and Mòtławë river valleys; however, in recent years, a substantial minority of these Transboreans have moved away from their traditional homelands into Lecian urban centers. The remaining fraction of the population is composed primarily of Namorese or Jathanis.

Religion

The traditional ethnic religion of the Lec people is Rodnéwiary, a monotheistic religion that modern anthropologists believe is ultimately descended from the pagan religions espoused by other Slavic ethnic groups in Borea. Unlike the pagan religions it is likely descended from, Rodnéwiary is focused solely around the worship of Rzékobòg, a water deity who supposedly led the Lec people to Lecia during the early common era. Rzékobòg is typically depicted as a three-headed dragon, with each head itself accorded a name and a personality: Létosc ("mercy"), Władosc ("might"), and Dólôj ("fate"). Rodnéwiary's religious scripture is known as the Uczénjë, or "teachings". The traditional head of Rodnéwiary is the Archbishop of Szimóngôcz; however, many of Rodnéwiary's high-ranking clergymen have been driven into exile by the Workers' Republic, and the current archbishop, Cërël XI, lives in exile in Asgård, Sjealand.

As Lecian censuses do not record the religion of respondents- ostensibly due to government espousal of state atheism- data regarding the religious affiliations of Lecians is sparse. While almost all Lecians practiced Rodnéwiary before the Second Lecian Revolution, barring a small Tastanist minority, the government of the Workers' Republic has continually targeted religious belief as part of what are termed "anti-superstition campaigns", banning public worship and the celebration of religious holidays. The overwhelming majority of Lecia's places of worship have been closed since the establishment of the Workers' Republic, forcing worship underground, as have all of the country's monasteries, and many members of the clergy- particularly Rodnéwiary clergy- were driven from the country as "counter-revolutionaries". In spite of this, external sources predict that at least 45% of the population still practices Rodnéwiary or another religion in private.

Education

Education in Lecia is overseen jointly by the Union of Teachers, Doctors, and Scientists and the Ministry of Education & Science, and is compulsory for all citizens between the ages of 6 and 18. Education in Lecia is divided into four levels: pre-primary, primary, secondary, and tertiary. Pre-primary education begins at three years and is optional but strongly encouraged, with the government providing tax benefits for families who enroll their children in preschool. Pupils are then enrolled in primary schools for six years beginning at age 6, and then in intermediary schools for two years from age 13.

Secondary education in Lecia lasts for four years, beginning at age 15. When beginning their secondary education, Lecian students are given the option to choose between a gymnasium, which proves a more general education, or a vocational school for those pursuing a career in the trades. Tertiary education is further divided, with students seeking to continue their education given a choice between four options: a vocational college, which provides further education and accreditation in the trades; a university, which provides education in the liberal arts; an institute, which provides education in the STEM fields; and a military academy. Further beyond these are professional schools, which provide doctorates, law degrees, and medical degrees.

All schools operating in Lecia are public and free to all; while the country had a tradition of private schools run by religious groups before the Second Lecian Revolution, these schools were either shut down or converted into public schools by the Workers' Republic. As of 2010, the country has a literacy rate of 99.4%.

Healthcare

The Lecian healthcare system operates using a publicly-funded single-payer model operated by the Union of Teachers, Doctors, and Scientists and the Ministry of Health, Welfare, & Sport. Medically-necessary procedures, such as physicals, surgeries, inoculations and dentistry, are covered; aesthetic procedures, however, are not. The Ministry of Health, Welfare, & Sport also regulates the prices of pharmaceutical drugs within Lecia.

The average overall life expectancy in Lecia is 70.5 years; the average female life expectancy is 74.7 years, and the average male life expectancy is 67.5 years.

Culture

Art

As monasteries and churches were common patrons of the arts, a significant portion of early Lecian artwork was religious in nature. Many ancient churches and monasteries in Lecia were intricately decorated with stone carvings and stucco, with some works from as early as the 9th century surviving into the present. Illuminated copies of the Uczénjë and other religious texts also form a significant portion of early Lecian artwork; the State History Museum of Lecia is in possession of more than 3,000 illuminated manuscripts. In addition, several illuminated histories- most famously the Record of Pious Rulers- were produced in Lecia during the 11th and 12th centuries.

Increased cultural contact and trade during the Four States Period resulted in a significant expansion of the Lecian visual arts during the period. The increasing popularity of frescoes in interior decoration, the commissioning of portraits by nobility, and patronage from the Church of Rodnéwiary caused the stature of painting to increase drastically; famous painters from the era include Òłëwir Kirzewski, Lùtór Rekowski, and Tëmon Sztalowski. The nationalist sentiments of the Òdroda sparked a trend of history painting and landscape painting, best embodied by the works of Oskar Błasiewicz, Mirosłôw Drifka, Jaroszcłôw Polkowski, and Władësłôwa Turzynski; this trend continued into the 1800s, under artists such as Jón-Mikòłôj Irenòwski and Adóm Szmãglinski.

Artistic movements such as Impressionism, Expressionism, and Futurism became popular in Lecia amidst the turmoil of the early 20th century, spearheaded by artists such as Aùgust Cynkski and Jùlian Retza; however, these movements received opposition from the Lecian monarchy, which associated them with anti-government and revolutionary groups. Since the Lecian revolution, the socialist realist style has dominated art in Lecia. Famous contemporary Lecian artists include Frãcëszka Łëzsynski, Oskar Myszka, and Teodór Olkuszski.

Architecture

Traditionally, building design within Lecia has been strictly limited by the availability of materials. Without easy access to wood, construction in Lecia has typically utilized rammed earth, adobe, or masonry. Decoration consisted either of stone carvings or stucco, and was characterized by intricate geometric designs, plantlike forms, and religious symbols. As trade between Lecia and its neighbors increased during the Four States Period, structures became increasingly complex, stone and brick steadily replaced rammed earth, and mosaics and frescoes began to replace carved decoration and stucco. Many public or monumental structures from this period are focused either around a central dome- typically pointed, though rounded domes were not uncommon- or a central garden.

Lecia was relatively peaceful and prosperous during the late 1700s and early 1800s, and Lecian architecture underwent a revival period as a result. Several buildings in the Neoclassical and Baroque styles were also constructed during this period, in an attempt to imitate the architecture of the powerful and prestigious states of Nordania.

During the unrest of the late 1800s and early 1900s, many examples of traditional Lecian architecture were damaged or destroyed. Furthermore, in the aftermath of the Second Lecian Revolution, traditional Lecian architecture was deemed "wasteful and decadent", and many structures were either destroyed, abandoned, or "refurbished" to remove traces of concepts deemed counter-revolutionary. The most infamous example of this was the Great Cathedral of Szimóngôcz, whose intricate religious frescoes were destroyed and replaced by murals in a socialist realist style. Most new constructions in Lecia since the Second Lecian Revolution have been built in the state-approved Constructivist, Brutalist, or Stripped Classicist styles.

Cuisine

Lecian cuisine is frequently described as rough and rustic, and is dictated heavily by the comparatively limited slate of ingredients commonly available within Lecia. The most important staple crops in Lecia are wheat and barley, which are traditionally used to prepare a variety of both leavened and unleavened breads such as płaska, weka, zakwas, kulycz, and bëranka. They are also widely used to produce beer. Potatoes, while not as prominent as barley or wheat, are another widely-used starch; potatoes are used to prepare dumplings, as a side dish, and for the preparation of vodka.

While Lecia's terrain and climate limit its agricultural potential, a wide variety of fruits and vegetables are present in Lecian cuisine. Eggplants, chickpeas, onions, olives and spinach are commonly-used vegetables; grapes, figs, apricots, limes, and raspberries are commonly-used fruits. Grapes are also widely used within Lecia to make wine. Nuts used in Lecian cuisine include hazelnuts, pistachios, and almonds.

Chicken, mutton, goat, and camel are commonly raised for meat within Lecia. Dairy is also widely used within Lecian cuisine; sheep, goats, and camels are widely raised for dairy farming within Lecia. Prominent dairy products of Lecian origin include smietana, bryndza, hładka, twaróg, oscypek, próstykwasza, and masłanka.

Famous Lecian dishes include sërenik, a kind of cheese bread; tarator, strained yogurt mixed with olive oil, cucumbers, and garlic, used as a dip; wrzëniki, filled potato dumplings usually served with sour cream; kéluszki, small potato dumplings commonly served with cheese; këbëny, a pastry filled with meat and onions; nadziewnik, an eggplant stuffed with ground meat; czuróka, mutton or goat roasted with onion; wëpôlca, a pan-fried chicken dish; zarieniki, meat grilled on skewers; koszulka, a dish of poached eggs roasted with tomatoes and onions; czenéka, a stew made with lamb, potato, and eggplant; piecka, mutton soup thickened with chickpeas; krëpë, a porridge served with chicken; pùrczeky, pastries filled with jam or cream; kójmak, boiled and caramelized sweetened condensed milk; sërenówka, a type of cheesecake prepared with twaróg; and limonówka, a pie made using lime juice and condensed milk.

A plate of wrzëniki served with sour cream.

Këbëny are widely sold as street food in Lecia.

Wëpôlca served with herbs and crushed hazelnuts.

A nadziewnik prepared with minced lamb.

A slice of limonówka topped with whipped cream and fruit.

Holidays

| Date | English name | Lec name | Recognized? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 1 | New Year’s Day | Nowirok | Marks the first day of the Gregorian calendar year. | |

| February 14 | Day of the Saints | Dzén Szacownych | Commemorates the deeds of Rodnéwiary saints. | |

| February 19 | Dôwacka | Dôwacka | Commemorates the supposed salvation of the Lec people from starvation during the Great Exodus. Celebration suppressed within Lecia. | |

| February 26 | Victory Day | Dzén Póbiedi | Commemorates the end of the Second Lecian Revolution. | |

| March 8 | Women's Day | Dzén Białky | Celebrates women and the women's rights movement. | |

| March 21 | Maslenica | Maslenica | Celebrates the spring solstice. Celebrated on March 20 on Gregorian leap years. | |

| April 14 | Rodnéwiary New Year | Stôri Nowirok Dzén Stwòrzenia |

Marks the first day of the Rodnéwiary calendar year, and the supposed creation of the world by Rzékobòg. Celebration suppressed within Lecia. | |

| May 1 | Labor Day | Dzén Robòta | Celebrates the working class and the international worker's movement. | |

| May 2 | Day of Arrival | Dzén Przëbëwac | Marks the supposed arrival of the Lec people in Lecia. Celebration suppressed within Lecia. | |

| June 21 | Sobótka | Sobótka | Celebrates the summer solstice. | |

| July 15 | Constitution Day | Dzén Kònstitucji | Commemorates the promulgation of the Constitution of 1828 by King Krësztof I. Primarily celebrated among the Lecian diaspora. | |

| August 10 | Day of Repentance | Dzén Pokuti | Dedicated to atoning the sins of the Rodnéwiary faithful. Celebration suppressed within Lecia. | |

| September 7 | Day of the Covenant | Dzén Przëmierza | Marks the covenant between Rzékobòg and Bògùsłôw I, and the supposed start of the Great Exodus. Celebration suppressed within Lecia. | |

| September 21 | Òrzniwinë | Òrzniwinë | Celebrates the fall equinox. | |

| October 7 | Day of the Revolution | Dzén Rewòlucji | Commemorates the beginning of the First Lecian Revolution. | |

| October 25 | Radonica | Radonica | Dedicated to the souls of the deceased Rodnéwiary faithful. Celebration suppressed within Lecia. | |

| November 14 | Army Day | Dzén Wòjsky | Celebrates the Workers’ Army of Lecia and the National Militia. | |

| November 30 | National Day | Dzén Nôródowi Dzén Òdroda |

Commemorates the Òdroda and the reunifcation of Lecia by King Stzefan. Primarily celebrated among the Lecian diaspora. | |

| December 21 | Kòlãda | Kòlãda | Celebrates the winter solstice. | |

| December 26 | Day of the Uczénjë | Dzén Uczénja | Marks the supposed compilation of the Uczénjë by Władëmar I. |

Literature

Much of Lecia's early literary tradition is religious in nature. The most famous work of this period is the Uczénjë; it is largely agreed that the Uczénjë was compiled by leading Lecian priests, possibly the Council of the Holy, following the arrival of the Lec people in Lecia, though the exact date of its creation is disputed. The Uczénjë consists of four books. The first two, Stwòrzeniô and Windzeniô, are narratives written in prose regarding the creation of the world and the arrival of the Lecs in Lecia; the third, Prësłowy, consists of codified religious law; the fourth, Napiszy, is a collection of religious poems and psalms. In addition to the Uczénjë, several major religious treatises and historical texts, such as the Record of Pious Rulers, survive from this early period.

A substantial portion of Lecian literature remained of a theological or religious nature during the Four States Period. Theologians such as Sobiesłôw Adómczyk and Kôrol Sztowski wrote treatises documenting the interpretation of Rodnéwiary doctrines, while Bògùsłôw Jełkowski- later Archbishop Tëmon IV- wrote On Heretical Faiths, which served both as an informative text and as a denunciation of faiths deemed heterodox by the Rodnéwiary clergy. However, this era also saw the appearance of the first secular, non-didactic works of literature; Pioter Trepczyk, a courtier to Teodór I of Ricérzów, was active as a poet and an author during the late 14th century, and Roman Jónkowski's collection of Lecian folk stories was first published in 1513.

The printing press contributed to an explosion of Lecian literature in the 16th and 17th centuries, which was further enabled by the peace and prosperity brought in the wake of the Òdroda. Poets such as Tobéasz Lëtôwski, Eupraksja Rózek, and Jón-Michòł Sikora were active during this period, as were authors such as Kazimierz Byzewski, Frãcëszk Krajnôski, Oskar Milsz, and Lôwrénty Sarbiewski. During the early 19th century, many works- such as those of author Tomôsz Szczesny and poets Tadéùsz Kamënski and Ambrorzy Takalski- were nationalistic, dealing with the fictionalized exploits of Lecian rulers and folk heroes; however, during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, writers such as Swiëtosłôw Krasinski and Patrik Michònski wrote works that critiqued or satirized the problems facing Lecian society.

As with most other forms of art, literary works produced in Lecia since the Second Lecian Revolution are expected to align with the principles of socialist realism. Famous contemporary Lecian writers and poets active within Lecia include Wiktór Andrzéjski, Zonja Łukôsziewicz, and Ludzmira Kulka. In addition, there is also an active writing scene in the Lecian diaspora, with works written by authors operating abroad and smuggled into Lecia. Contemporary Lecian authors belonging to the Lecian diaspora include Frãcëszka Meklenbùrski, Jerzy Olkowski, Miłosłôwa Somòninski, and Emil Wróblewski.

Music

Lecia has a long musical tradition, with records of traditional musical instruments such as the swistek dating back to the 400s CE. Other traditional Lecian musical instruments include the dychek, as well as local variants of the lute and the hammered dulcimer. The earliest surviving written arrangements for music in Lecia have been dated back to the 13th century. Many of these early songs are hymns or psalms, derived from segments of Rodnéwiary holy texts such as the Uczénjë. In addition to religious songs, Lecia developed a rich folk music tradition, which would prove an inspiration to many later Lec composers.

As with many other forms of Lecian art, music was patronized extensively during the Four States Period. Music from this period drew heavily from Lec folk music, but it also frequently sought to imitate courtly music from nearby nations such as Namor, Qaradalai, and Luziyca. This period is the first period from which the names of individual composers become known; famous Lecian composers from the period include Fridrëch Cyra, Sobiesłôw Jaszewski, Irenéùsz Lãsinski, and Bògùsłôw Szpilek.

In the wake of the Òdroda, many Lecian composers drew increasing influence from traditional folk styles and tunes, such as the oberek and the lecque, or from Nordanian styles of musical composition. Nordanian-style concertos, sonatas, and symphonies became the dominant structures of musical compositions, replacing traditional and Monic-derived structures. Nordanian influence on Lecian music also deeply affected instrumentation, as many traditional instruments were abandoned in favor of Nordanian counterparts. Leading composers from this period include Jigór Gòlniòwski, Krësztof Lipinski, and Wincénty Tomôszki.

The rise of musical nationalism in the 19th century resulted in a wave of music drawing heavily from Lecian folk music under composers such as Józef Brùski and Aleksander Szrëder during the early 1800s; increased turmoil during the latter half of the century, however, provoked a counter-movement of music critical of institutions such as the monarchy and the clergy, led by composers like Andrzéj Kùmiéga and Dobrosłôw Przëbyszéwski. After the rise of the Workers' Republic, music was supposed to reflect the principles of syndicalism, extol the progress made since the Second Lecian Revolution, and reflect the liberation of the workers; retaining the favor of the state became increasingly important for composers. Famous contemporary classical composers from Lecia include Władëmar Kónski, Môrcën Sokólski, Bògdan Szëmrejski, and Feliks Tëmonowicz.

More modern genres of music, such as rock, rap, and pop, have had a mixed relationship with the Lecian government. These genres were heavily associated with counter-culture and dissident movements, and as a result the Lecian state attempted to suppress them, barring them from radio play and public performance. In recent years, the Lecian government has loosened its restrictions on these genres; this decision has elicited praise from some, but it also sparked allegations that the government was trying to co-opt these genres with inoffensive, state-sanctioned artists such as Highway One and Mikòłéta Sosna. Nevertheless, protest music remains a common feature within these genres in Lecia, epitomized by artists such as Owczarek, Nowi!, and the Addicts.

Theater

As with most other forms of Lecian artwork, early Lecian theater was largely religious in nature. Particularly common was a type of play known as a nauczania, which depict scenes from the first two books of the Uczénjë; nauczanie were typically organized by local churches or monasteries in order to relate these stories to illiterate peasants, and were often held to celebrate religious holidays. Nauczanie remained a common feature of Lecian theater, easily accessible to all classes of Lecian society, for centuries; however, they have been widely suppressed since the Second Lecian Revolution.

While a limited courtly tradition of theater arise during the Second Chiefdom, the Four States Period saw this tradition greatly expanded. This was in part due to extensive patronage of the arts by ruling authorities; during the last two centuries of the period, the printing press also allowed for the publication and distribution of plays on a previously unprecedented scale. Playwrights such as Michòł Érdmanczyk and Kamël Gombrowicz produced elaborate, standardized nauczanie for the archbishops of Szimóngôcz, while Jón-Paweł Kleczewski, Kasper Łomnicki, and Zenón Mësztòwt produced tragedies, romances, and comedies based on traditional Lecian folk tales or the works of early Lecian authors.

The peace and prosperity of the Òdroda resulted in the rise of a new wave of Lecian playwrights. King Sztefan I was a great patron of theatrical works, and commissioned several playwrights during his lifetime; most notable among these was Jùlian Felski, who produced several histories for Sztefan I, including Tëmon IV and Jùlja of Bónôwy. Other famous Lecian playwrights from the 17th and 18th centuries include Wisłôw Dãmbrowski, Krësztof Lipinski, and Ludwik Slówinski. The era also saw the establishment of the National Theater of Lecia.

Histories remained popular topics for theater during the early 19th century amidst the rise of Lecian nationalism; this nationalism also resulted in a resurgent interest in adapting Lecian folk tales and novels for the stage. Leading playwrights of this movement included Antón Czyrzewski and Szimón Kaszor. During the latter half of the 19th century, however, playwrights such as Andrzéj Kùmiéga and Eusebiusz Pliska wrote plays containing biting social commentary, satirizing the monarchy and the clergy, and criticizing the government. Kùmiéga's comedy The Cloister and Pliska's drama The Death of King Krësztof stand out as among the most famous examples of this trend, and triggered widespread controversy when they were released. This trend continued into the early 20th century, spearheaded by playwrights such as Irena Kokòszynski; Kokòszynski was jailed for five years following the release of her inflammatory play The Vultures.

The Second Lecian Revolution and the imposition of the socialist realist art style greatly affected Lecian theater, with works expected to emphasize revolutionary ideas and the progress made by the Workers' Republic. Certain playwrights, such as Roscisłôwa Kowalczëk, Feliks Tëmonowicz, and Łukôsz Wiékowski excelled with the support of the Lecian state; Kowalczëk's Zofia Kòscérski and Tëmonowicz's The Siege of Ricérzów and Juozapas Kairys in particular are considered to be some of the best works of Lecian theater. Others, such as Sztefan Lupa and Józefina Pòłczynski, had a mixed or confrontational relationship with the Lecian regime; both Lupa and Pòłczynski ultimately left the country and continued their work abroad.

Sports

The most popular sport in Lecia is handball, which largely subsumed a local variant known as hazéna during the 20th century. The People's Handball Association oversees the national handball team and the Handball Superliga; the 2017 champions of the Handball Superliga are KR Rewòlucjô Bónôwy. Close behind handball in popularity is soccer. Soccer in Lecia is overseen by the People's Football Association, which in turn oversees the Football Superliga; the 2017 champions of the Football Superliga are KS Dinamit Ricérzów. Lecia's national soccer team has appeared in the Coupe d’Esquarium once. Other popular ball games in Lecia include futsal, volleyball, and basketball.

Martial arts, including zuudou, sambo, swordsmanship, and archery, are moderately popular in Lecia. A traditional form of wrestling, known as paléczna, has also regained some popularity in recent years. Racket sports such as tennis and badminton were popular among the upper classes before the Second Lecian Revolution, but have lost popularity since. The board game go, originally brought to Lecia from Namor, is played competitively within Lecia and was traditionally the most popular strategy board game in the country, but it has since been surpassed by chess.

Sport in Lecia is overseen by the Union of Artists and Athletes, which serves both as a union for athletes and as the ultimate sports governing body within the country, overseeing and managing the governing bodies of individual sports. Unique to Lecia are a set of organizations known as "voluntary sport societies", formally aimed at expanding public access to sport and physical education. These sport societies are usually, though not always, associated with institutions such as labor unions or the Lecian military. In addition to running community centers and training facilities, these organizations also operate individual teams in a variety of sporting events. Major voluntary sport societies within Lecia include Robòta, Zenit, Kòsa, Dinamit, Naprzód, and Rewòlucjô.