Church of Nortend: Difference between revisions

| Line 131: | Line 131: | ||

Holy Matrimony is a sacrament of union between a man and woman. It is considered dissoluble by temporal power, although it may be annulled, as may any other sacrament for lawful cause. It is, however, considered soluble by God and divorces are recognised in certain cases such as adultery. Remarriage after a canonical divorce, or release from vows, is not prohibited, except that the priest may not accept vows on behalf of God between an adulterer and his mistress. Holy Orders is the method whereby a layman is ordained to the deaconhood, priesthood or bishophood. | Holy Matrimony is a sacrament of union between a man and woman. It is considered dissoluble by temporal power, although it may be annulled, as may any other sacrament for lawful cause. It is, however, considered soluble by God and divorces are recognised in certain cases such as adultery. Remarriage after a canonical divorce, or release from vows, is not prohibited, except that the priest may not accept vows on behalf of God between an adulterer and his mistress. Holy Orders is the method whereby a layman is ordained to the deaconhood, priesthood or bishophood. | ||

===Fasting=== | |||

The Church does not distinguish between abstinence and fasting, calling both fasting. Fasting involves the avoidance of flesh meat (fish is not considered meat), although oil, eggs and dairy are allowed, and limitation of meals to a dinner of four courses or fewer after sunset and two collations, making a total of three courses or fewer) during the day. Adventtide and Lententide are the two fasten tides, which serve as preparation for the high tides of Christmastide and Eastertide respectively. In Advent, Saturdays are additional fasten days, whilst all days Sunday to Saturday are fasten days in Lent. | |||

Canon law also requires that people wishing to receive Holy Communion fast from the end of Compline the night before. No food may be taken except for a “mass collation” which is a collation eaten at least one hour before receiving. A traditional mass collation consists of bread and an omelet with herbs and mushrumps, as well as fruit. | |||

==Liturgy== | ==Liturgy== | ||

Revision as of 05:18, 19 July 2021

| Church of Nortend | |

|---|---|

| Ecclesia Erbonica | |

St. Peter's Cathedral in Lendert-with-Cadell is the seat of the Lord Bishop of Lendert. | |

| Classification | Catholic and Reformed |

| Scripture | Bible |

| Polity | Episcopal |

| Governour | The Sovereign |

| Primate | Sebastian Williams, Lord Archbishop of Sulthey |

| Region | Great Nortend |

| Language | Latin and English |

| Liturgy | Cardican Rite |

| Headquarters | The Cathedral and Priory Church of Saint Laurence, Sulthey |

| Separated from | Roman Catholic Church 1614 |

| Members | 29 million |

The Church of Nortend, in Latin the Ecclesia Erbonica, is the state church of Great Nortend. It is established under the Proclamation of Manfarham, the Statute of Limmes and the Statute of Supremacy. The Sovereign of Great Nortend is the supreme temporal head of the Church, being Governour of the Church Mundane. For spiritual authority, the Church of Nortend maintains the historic episcopate and apostolic succession. Ecclesiastical power is vested in the Archbishop of Sulthey who is Primate of Erbonia, as well as the Archbishops of Limmes and Rhise, fourteen bishops suffragan and three abbots territorial.

History

Early Christianity

An abbot, later canonised as Saint Laurence of Sulthey, is widely credited for the founding of the establishment of the modern-day Christian church in Great Nortend in the 8th century. The native Ethlorekoz and the later influx of Arlethians, the Nords, Sexers and Cardes, practised heathen religions. Laurence, arrived on the shores of the then Kingdom of Nortenland in AD 744 during the reign of Egbert, on a mission ordered by Pope Zachary I. He founded a church on the Isle of Sulthey in 749, the year which is now generally considered the start of the Church in Great Nortend, on a site which is now the Church of Saint le Cross.[1] He also founded the first monastery, which became Sulthey Abbey, two years afterwards in 751. Laurence served for over thirty years as the first Bishop of Sulthey.

After Egbert died in 753 after being mortally wounded by an arrow during battle with the Hambrians, the young Murish prince Hartmold de Mure took the Nortish throne in 756. He had earlier converted in 750, at the age of 30. During his reign, and the subsequent reigns of Æthelfrey, Erwin and Edmund the Good, the people across the Kingdom were converted and the Church and Christianity became the dominant framework for political and religious discourse.

Middle Ages

The Church flourished in the Middle Ages, in a frenzy of religious piety. Gothic architecture was introduced during the late 12th century, supplanting the existing Nortish style which was dominated by wooden construction in the densely forested North above Golder's Line and stone construction below. By the 13th century, nearly every manor had at least one church and across the country numerous religious houses, chantries and chapels were founded. Within Lendert-with-Cadell alone, 52 churches had been built by the time the rebuilt Saint Peter's Abbey was completed in 1272.

Declaration of Sulthey

Through the 16th century, the Church faced increasing conflict with the King over the exercise of temporal power by the Pope. Thomas Akeep, who was Provost of Sulthey, railed against „ultramontanism” and stridently avowed the temporal primacy of the King. He, along with the major (secular) Chapter of Sulthey Cathedral, published the „Declaration of Sulthey” in 1530, consisting of four articles :—

- The Church only has Power over Matters spiritual, and the King therefore is not subordinate to the Church in Matters temporal and cannot be deposed by the Church nor can his Vassals be freed from their Oaths.

- The Judgment of the Holy Father is not absolute in Matters spiritual without the Consent of the Councils and Bishops.

- The Powers of the Church are only exercised when in accordance with divine Law established through the received Customs and Traditions.

- The King has the right to call Councils and with their Consent make laws concerning Matters spiriual and the Pope's Bulls and Letters may not be promulgated without their consent and that of the King.

Though the Declaration did not necessarily amount to heresy, the anti-Papal articles offended Clement VII than in 1534 he refused to permit the appointment of Thomas de Akeep to the See of Chepingstow, to hold political office as the Lord High Chancellour. Clement's refusal resulted in the wide promulgation of the „Declaration” in print, despite it being thitherto a relatively obscure pamphlet, leading to the growth of stronger tensions throughout the Kingdom and calls for reform of the Church.

Small Schism

From 1545 to 1563, Erbonian prelates attended the Council of Trent but there was no effective changes which satisfied the growing opposition to the Papacy. Over the next fifty years, various reformist sects developed advocating for more and more extreme reformation along Protestant lines. Spurred on by his ministers, in 1614, the Proclamation of Manfarham was issued by Alexander I, followed by the Statute of Limmes later that year and the Statute of Supremacy in 1615, which rejected the authority of the Bishop of Rome, and de facto established the Church of Nortend as fully independent from the See of Rome. The States were passed with the consent of the Privy Council and later ratified by the Parliament in 1632.

A legend surrounding the proclamation relates that the then-Archbishop of Sulthey, Richard Cainmaring, received a message from the Holy Ghost in a dream commanding that, „Mine house shall be cloven and I shall make thy Lord my Governour over my flock”. The King and Archbishop of Sulthey, after public assent to the Statute, were excommunicated by the Pope . The Statutes referred to the „Declaration of Sulthey” and upheld them. Though loyalists were not initially legally persecuted for their support of the Roman church, the controversy was, in the early and mid 17th century, increasingly manifested through violence between both sides.

This so-called Small Schism (distinguished from the Great Schism from the Eastern Church) was generally popular amongst the common people and nobility, although it was opposed by most parish clergy and monastics who were mainly fearful for their positions. In 1618, Alexander I offered to reinstate the title of „cardinal” for those clergy who recognised his supremacy, provided that they could prove their right to the use of the title by custom prior to the 1567 decree of Pius V which restricted its use to the cardinals of Rome. This had been seen as an offensive assertion of Papal and Roman supremacy by the Nortish Church, which had used the title for various priests holding certain benefices.

Though loyalists were not initially legally persecuted for their support of the Roman Catholic church, the controversy was, in the early and mid 17th century, increasingly manifested through violence between both sides. Simmering violence came to a head when the 12th Duke of Cardenbridge was captured and hanged by the Loyalist Abbot and monks of Staithway in 1668. The 13th Duke introduced a Bill into the House of Lords after the death of Alexander I who had opposed criminalisation later that year, to criminalise allegiance to the Pope, leading to the use of the term „Cardican” to refer to the Church of Nortend. Under the Act, many clergymen were executed for refusing to renounce against the Pope and escalated with the trial and execution of the Six Heretics, six clergymen who plotted with the Pope to invade Great Nortend and restore the Church in 1670 during the first few years of King William I's reign. Meanwhile, the Acts of Cleaving forming the combined Kingdom of Nortend, Cardoby and Hambria had passed in 1642 and established the Church of Nortend as the established church of Hambria as well.

Lutheran influence

The [Albish Magnanimous Revolution] in 1665 led to the flight of Edmund III, the then [Albish] King of the House of Oln to Great Nortend. He was recognised and received by Alexander I and created the Earl of Scode, and granted the important Castle of Scode in Barminstershire. He gained influence at Court and introduced a true Lutheranism to the Nortish Church already receptive to Protestantism.

Under William's reign, the young Lutheran-leaning Cardinal Henry Frympell was consecrated Archbishop of Sulthey in 1679, after John Bull, mysteriously died during a banquet. Though he had a moderate theology, Cardinal Frympell advocated strongly for a translation of the Bible into English. The „King James's Bible” had been published in English in 1611, a few years prior to the Proclamation of Manfarham, and was seen as a strong contender. After several draught versions, Frympell's translation of the Old and New Testments (including the Apocrypha) was approved by William I in 1699. It drew heavily from the King James's Bible and the older Great Bible for the Apocrypha and Psalms, as well as the German Luther Bible for inspiration, phrasing and guidance. Copies were disseminated to every church and school, leading to its widespread adoption. Its wording and style was praised by men of all churchmenship, although theological concerns abounded.

Cardinal Frympell also instigated the first major reform of the church itself in his second year in office, abolishing the minor orders and the subdiaconate as sacramental orders on account of their non-existence in scripture, and instead combined the subdeacon's duties with that of the holy-water porter, later known as the parish clerk.

Edmundian Reforms

The Bible translated into the „understanded tongue”, the Lutherans turned to the offices and mess for translation and reform. After Cardinal Frympell's death in 1702, the even more strongly Lutheran Cardinal George Miers was appointed Archbishop of Sulthey. Before he could be installed, William I unexpectedly died at the age of 44 and the young 22-year-old Edmund VI acceded to the throne, crowned by the Archbishop of Rhise, Cardinal August Lewencort. Cardinal Miers finally was installed in 1704, as one of the first acts of Edmund's reign. However, with the powerful „broad-church” influences of William and especially Frympell gone, Edmund needed to satisfy both ends of his church.

A „Commission for the Translation of the Divine Service”, headed by Sir Charles de Henfott, 7th Bart., presented its draughts for a new Breviary and Missal in English to Edmund the next year in 1705. However, it immediately proved much more controversial than Frympell's well-received Bible transltion. It satisfied neither party—the so-called Frympellites argued that it remained too monastic and unsuited for Lutheran-style public prayer and worship. On the other hand, the so-called Akeepians, who now also rejected the Bishop of Rome's spiritual jurisdiction over anywhere but his own see, were in favour of only very minor simplification and the retention of Latin wheresoever possible.

Owing to his young age, a compromise was brokered by Edmund between the two camps with assistance from the 13th Duke of Cardenbridge who was seen, despite his opposition to the papacy, to be otherwise theologically neutral. Under the proposal, the offices would be only conservatively simplified and reordered to make them more practical for public and private worship. In a concession to the Frympellites, and an increasingly large faction of the Akeepians, the use of Latin in the liturgy was suppressed except in private chapels in favour of a translation into English. However, the authoritative and official documents and texts of the Church remained in Latin. The canon Quia solliciti, issued by Edmund in 1711, formally authorised and prescribed inter alia the new Book of Messes and Book of Offices for all public and corporate worship.

Exponential influence

The dominant „small-l” Lutheranism in the Church of Nortend in the early 18th century soon began to be threatened by the increasing trade and improved diplomatic relations with the Exponential Empire and its Occidentes Province (now the Aurora Confederacy) which begat a small but growing „Catholic” renaissance at Court and throughout high society.

In 1731, Augustus I of Aquitayne arrived in Great Nortend seeking support for Aquitaynian independence from the Exponential Empire. He quickly arranged a marriage with Anne-Louise, 28, the youngest daughter of William I with the blessing of Edmund VI, who was desirous of counteracting the growing popish influence with support from another Lutheran realm.

After the death of Edmund VI in 1736, however, relations with the Exponential Empire improved dramatically. Immediately after his passing, Cardinal Archibald Lofthouse, then Lord Bishop of Rockingham, sensationally declared his allegiance to the Roman Church, revealing a underground network of papism hidden, albeit scattered under the pretence of Lutheranism. Mary's accession to the throne was seen as untimely by the notionally dominant Frympellites, who were highly concerned she would lack the authority to counteract this growing Catholic feeling. Thus, she was pressured by her Parliament into declaring the suspension of the initiation of any novices to religious establishments in 1737 and appointing more Frympellite bishops and clergy by passing the Abjuration Act in 1738.

The Olnite Matter

Unfortunately for the Frympellites, Mary announced in 1740 her intention to marry Charles de Oln, the 5th Earl of Scode, of the House of Oln in Albeinland. Charles was of an Akeepian and Catholic leaning churchmanship. The marriage was vigorously opposed by the Frympellites. In Parliament, two factions developed known as the „Scodeliers” and the „Droughers”, which supported and wished to „draw asunder” (whence „drougher”) the marriage respectively. In the end, the Droughers were unable to stop the marriage, and Mary wed the Earl of Scode in 1742 at the age of 27.

This apparent act of alliance with the Catholic Exponential Empire, along with the almost next-day restoration of friendly ties with the Exponential Empire immediately drew costernation around the region. Notably, Mary disowned her aunt Anna-Louise after the latter condemned the marriage as a betrayal of Mary's late father, Edmund VI. Nonetheless, nothing could repair the damage wrought to the Frympellites, especially after the islands of St. Parth and Hastica were returned to Great Nortend. Thenceforth, following this ,,Akeepian Settlement”, the Akeepian faction grew to dominate the Church.

Doctrine

The doctrine of the Church of Nortend was and is based on the traditional doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church and Orthodox Church, with some minor influence from Lutheranism. The official doctrine of the Church was declared in 1801 by Catherine of Hall in the 42 articles in the Erbonia Ecclesiastica to settle for once and all the disputes between the Akeepians and Frympellites. Inter alia, it confirms the authority of the Apostles' Creed, the Nicene Creed, the Athanasian Creed, the virgin birth, the two natures of Christ, the Holy Trinity, the seven sacraments, the belief in the real presence, the belief in continuous rightening by grace through faith with works, the belief in predestination, the prayer for the dead and the bidding of saints, and the temporal supremacy of the Crown.

Sacraments

The Church of Nortend recognises the seven sacraments of Baptism, Confirmation, Eucharist, Absolution, Unction, Matrimony and Orders. These are said to work ex opere operato meaning that they derive their power not from the holiness of the minister, but from Christ himself, with the minister acting in persona Christi.

Holy Baptism is the first sacrament of initiation into the Church for a catechumen. Infant baptism is practised, involving the immersion or pouring with water whilst reciting the Trinitarin baptismal formula, “I baptize thee in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.” Holy Confirmation is conferred around 14 to establish one in the faith by receiving the seal of the Holy Ghost. Holy Eucharist is the sacrament which completes a person's initiation into the Church as a Christian. It is usually given by intinction at Mess, where bread and wine are consecrated into the body and blood of Christ. The Church of Nortend believes in the real, essential and substantial presence of Christ, but not a fleshly or bloody carnal presence. The nature as to how this occurs is considered a mystery.[2]

Holy Absolution is the sacrament of reconciliation to God, and the forgiveness of sins. Both non-sacramental and sacramental absolutions are given in the Church, the former through the Indulgentiam in Divine Service expressed as a prayer, and the latter though private confession, where a priest directly absolves the penitent. Holy Unction is a sacrament of cure given to the sick to strengthen his spirit against suffering, illness, death, temptation and the Devil, and to strengthen his body from infirmities and illness if conducive to salvation.

Holy Matrimony is a sacrament of union between a man and woman. It is considered dissoluble by temporal power, although it may be annulled, as may any other sacrament for lawful cause. It is, however, considered soluble by God and divorces are recognised in certain cases such as adultery. Remarriage after a canonical divorce, or release from vows, is not prohibited, except that the priest may not accept vows on behalf of God between an adulterer and his mistress. Holy Orders is the method whereby a layman is ordained to the deaconhood, priesthood or bishophood.

Fasting

The Church does not distinguish between abstinence and fasting, calling both fasting. Fasting involves the avoidance of flesh meat (fish is not considered meat), although oil, eggs and dairy are allowed, and limitation of meals to a dinner of four courses or fewer after sunset and two collations, making a total of three courses or fewer) during the day. Adventtide and Lententide are the two fasten tides, which serve as preparation for the high tides of Christmastide and Eastertide respectively. In Advent, Saturdays are additional fasten days, whilst all days Sunday to Saturday are fasten days in Lent.

Canon law also requires that people wishing to receive Holy Communion fast from the end of Compline the night before. No food may be taken except for a “mass collation” which is a collation eaten at least one hour before receiving. A traditional mass collation consists of bread and an omelet with herbs and mushrumps, as well as fruit.

Liturgy

The Church of Nortend places a great deal of emphasis on liturgy, or divine service. The full authorised liturgy is set out in three books, known as the Books of Divine Service, which replaced the former rites of Sulthey, Chepingstow and Limmes. The three books are the the Book of Messes, the Book of Offices, and the Book of Rites, which were promulgated in 1709, 1710 and 1713 respectively. Their use was bidden in 1711, by Edward VI in the canon Quia solliciti, though the final book had yet to be published.

The services for the mess (mass in Erbonian English) and daily offices are set out in the Book of Messes and Book of Offices respectively. The order for the administration of the sacraments such as baptism, confirmation, marriage, ordination of bishops, priests, deacons and clerks, confession and unction, as well for funerals, coronations, investitures, processions, the visitation of the sick, blessings, prayers and thanksgivings are given in the Book of Rites.

The Books of Divine Service are used with the Holy Bible according to Frympell, and the Book of Chaunts from 1730. The latter includes all of the authorised plain chaunt melodies for use in divine service. In later printings, the liturgical chaunts are usually included in the Books of Messes, Offices and Rites already, obviating the need for a separate book.

Offices

The daily cycle of offices is the fundamental basis of the Cardican liturgy. The offices of Mattins, Vespers and Compline are chaunted daily in the morning, evening and at night. One of the three offices of Tierce, Sext or Nones is chaunted during the day around noon, depending on the Calendar, which is then followed by the High Mess of the day, if sung. The offices are all structured similarly, beginning with prayers and versicles, followed by three psalms with antiphons, then lessons or chapters taken from scripture, followed by a responsory and ending with more prayers and versicles.

Mess

The mess is the principal liturgy in the which Holy Communion is confected and given. The Antecommunion liturgy begins with an Introit anthem, followed by the Kyrie, the Gloria, and the Collects. Then there are three lessons, normally from the Histories, the Epistles and the Gospels respectively, divided by the Gradual responsory and the Alleluya with Sequence. Thence follows the Communion Liturgy, beginning with the Offertory anthem, then the Preface, the Hagios and then the Canon. After the Canon is the Pater noster, the Agnus Dei and the Pax, followed by the Communion proper. The mess may be celebrated as a high mess, with singing, or as a low mess, with the words said. A high mess may also be either solemn, with deacon and subdeacon, or simple, with two clerks assisting instead.

At least one mess must be celebrated monthly in all parish churches, and in many churches they are celebrated daily or even multiple times a day. Messes are always said on feast days. The most attended mess is the Sunday high mess, which is celebrated on Sundays at noon. Many churches also offer morrow messes, which are said immediately after Mattins in the early morning by the morrow-mess priest. Churches with attached chantries also have chantry messes throughout the morning, celebrated by dedicated chantry priests. These messes are usually Requiem messes, said for the expectant soul of the grantor and the whole church expectant.

Language

One of the changes sought by Cardinal Frympell was to replace Latin in divine service with an „understanded” tongue, i. e. English. Since to the introduction of Henfott’s reformed liturgy in 1711, services are normally chaunted through in English. However these are merely approved translations of authoritative ecclesiastical Court Latin texts. The Latin liturgy is still used in certain private chapels, generally those associated with the universities and schools. For public (and private use), a semi-archaic poetic form of Erbonian English is used.

- Our Father which art in Heaven,

- hallowed be Thy Name;

- Thy Kingdom come,

- Thy Will be done, in Earth as it is in Heaven.

- Give us to Day our daily Bread,

- and forgive us our Trespasses,

- as we forgive them that trespass against us;

- and lead us not into Temptation,

- but deliver us from Evil.

- For Thine is the Kingdom, and the Power, and the Glory,

- world without end. Amen.

The Ave Maria

- Hail Mary that art much graced,

- the Lord is with thee.

- Blessed art thou amongst Women,

- and blessed is the Fruit of thy Womb, Jesus.

- Holy Mary, Mother of God,

- pray for us Sinners,

- now and at the Hour of our Death. Amen.

The Credo in Deum

- I believe in God the Father Almighty,

- Maker of Heaven and Earth,

- and in Jesus Christ his only Son our Lord,

- which was conceived through the Holy Ghost,

- born of the Virgin Mary,

- suffered under Pontius Pilate,

- was crucified, dead, and buried;

- He descended into Hell;

- The third Day he rose again from the Dead;

- He ascended into Heaven,

- and sitteth on the right Hand of God the Father Almighty;

- From thence he shall come to judge the Quick and the Dead.

- I believe in the Holy Ghost,

- the Holy Catholick Church,

- the Commonship of Saints,

- the Forgiveness of Sins,

- the Resurrection of the Body,

- and the Life everlasting. Amen.

Calendar

The Church of Nortend follows the Gregorian calendar, having been introduced in 1582 prior to the Great Schism in 1614. The liturgy is structured around the ecclesiastical Calendar, which is an interlaced set of cycles of varying lengths. The fixed cycle begins on Michaelmas every year and specifies the dates of the immovable feasts such as Christmas, Epiphany, Candlemas, St. John's Day, and Martinmas. The moveable Paschal cycle changes annually based on the computation of Easter, setting the dates for Lent, Good Friday, Easter Day, Whitsunday, Ascension, Trinity &c. Liturgical days are parted into principal feasts, double feasts, semidouble feasts, simple feasts, fairs and fasts, with complex rules in conjunction with the calendar cycles. The weekly cycle also affects the calendar, as the liturgy changes depending on what day of the week it is.

Traditions

Music

Both choral and congregational music play a large part in Cardican liturgies. Most public offices and all high messes are sung, or “chaunted” , usually accompanied by a pipe or reed organ. Texts are chaunted in monophonic plainsong, often harmonised by the choir, or in polyphonic figured song by the choir. In the office, psalms are communally chaunted antiphonally. Furthermore, hymns are sung after the psalmody and after the final responsory. In addition to traditional Gregorian hymns translated into English and sometimes harmonised, there are a large number of “new” hymns which are published in various hymnals. These are from various sources, including international Roman, Lutheran and Anglican sources.

The prescribed plainsong melodies are provided in the Book of Chaunts. Plainsong in the Cardican tradition is performed in a mensural style, in contrast to the equal style promoted by the Roman Solesmes school. It is only rarely sung without accompaniment. The organ and choral harmony provided in a typical Cardican service means that plainsong melodies tend to take on a “fuller” sound, more reminiscent of four-part hymns than Gregorian plainsong.

Books

There is a strong tradition of hand engrossed liturgical manuscripts in the Church of Nortend. After the advent of the printing press, the mediaeval tradition of scribing manuscripts on parchment or paper declined for ordinary use. However, expensive illuminated manuscripts, of liturgical books, continued to be created for the use of the nobility and Royal courts as a mark of prestige. Similarly, hand engrossed parchment, sometimes illuminated, is still used for deeds, statutes, charters, writs and other formal legal documents. All of these documents, as well as fully noted Books of Messes and Offices, used on solemn feasts and special occasions, continue to be produced by monastic houses around the country.

Architecture

Erbonian church architecture is predominantly Gothic, although many churches have an older Arlethic origin. An important difference with Roman church architecture is the focus on division of the church interior. Generally, there is a strict division between the nave and the chancel, the former being the preserve of the laity and the latter the preserve of the clergy.

In parochial churches, the nave and chancel are separated by a rood screen, its name deriving from the large rood hung over the screen. This screen has a single central doorway, and is usually of light open tracery. On the other hand, in collegiate churches, including cathedral, monastic and religious churches, the pulpit screen is constructed with two transverse walls supporting the pulpit platform overhead. The pulpit screen is usually constructed of stone.

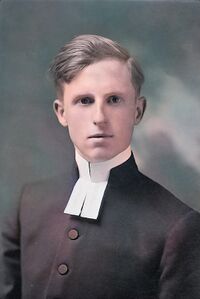

Clerical dress

Ordained ministres in the Church of Nortend are required to wear the prescribed clerical dress at most times outside of the liturgy (the vestments for which are prescribed in the liturgical books). This is very strictly enforced, and clergymen are often brought before the ecclesiastical courts for this trangression. Per the canon In nova tempora, non-liturgical clerical dress is divided into house dress, undress and full dress.

House dress

House dress is worn in informal or casual situations, such as at home or in the country or when doing menial labour. It consists of a suit or coat and trousers of dark, sombre colour worn a matching dark neck-height waistcoast. A starched clerical collar is still worn, but without bands. The coat is similar to a short frock coat and is usually designed to button up to the neck, and has a V-shaped collar cutout.

No gown is worn, and secular hats are worn. When impractical, the clerical collar, jacket and even waistcoat may be dispensed with in favour of a shirt with soft open collar. The trousers may also be replaced with knees or short trousers where appropriate, such as when in the country or in hot climates.

Undress

Undress is worn at semi-formal or formal non-liturgical situations. It is the ordinary „on duty” street dress of ordained ministres. It consists of the short frock, trousers, the gown and a hat. The short frock, or apron cassock, is a knee-length single-breasted frock worn with the cincture. A frock coat may also be worn over the short frock when thought wise.

Starched standing collars with starched bands are always worn. The gown is only worn when in and around the church and when academic dress is worn. The gown worn is the undress gown, which is normally black. The traditional hat worn is the liturgical soft cap. When the gown is not worn, however, a brimmed round hat or top hat is more often worn. A cape may also be worn in such cases. Some archdeacons, cardinals and bishops wear wigs daily, but this is nowadays very uncommon.

Evening undress is much the same, but silk is used for piping, buttons, the cincture, lining and cuffs rather than wool. Silk stockings and evening shoes are also usually worn, although patent leather is forbidden. A silken cape may also be worn, unless the gown is worn.

Full dress

Full dress is worn at non-liturgical state, ecclesiastical and legal occasions. It consists of the short frock worn with breeches. The gown worn is the full dress gown with hood. Most doctors wear scarlet gowns with coloured facings. Certain dignitaries wear a long train on their gowns. The soft cap is worn. Wigs are always worn by those entitled to them.

Structure

The Sovereign is recognised as the „Governour of the Church Mundane”, being the „highest power under God in his Dominion” with „authority over all persons in all matters temporal”.

The Church of Nortend distinguishes between four orders of clergyman, that of the bishop, priest, deacon and clerk. Of the four, only the first three are conferred by the sacrament of holy orders and are known as clerks in holy orders. Bishops may only be ordained by three other consecrated bishops, whereas a priest or deacon may be ordained by any single bishop. Once ordained, it is not possible to relinquish the clerical state. Clerks in holy orders are not permitted to be married or to marry.

The mere clerk subsumes the historical minor orders. The senior-most clerk is the parish clerk, often known simply as the clerk, which merged with the former holy order of subdeacon in 1672. Lesser clerks include the crucifers, thurifers, cerofers and acolytes, as well as choristers. Organists are also usually admitted as clerks. University undergraduates and graduates rank as academical clerks, a status which is normally conferred during matriculation. As the clericate is not a holy order, a clerk can relinquish this status by abandonment or by deed and does not receive tonsure.

Aside from the orders, the Church of Nortend also confers titles or dignities to persons within its hierarchy. These include the dignities of cardinal, archbishop, bishop suffragan, bishop coadjutor, archdeacon, dean and rector.

The cardinalate is a personal dignity conferred upon either a bishop or a priest who is particularly distinguished by royal favour. Every cardinal has a titular church to which he is incardinated to.

Organisation

The Church of Nortend is divided into three ecclesiastical provinces, sci. a metropolis in Orthodox terminology, headed by an archbishop. These metropolitan provinces are not to be confused with civil provinces.

Each province is divided into dioceses, headed by a bishop. A diocese may have additional titular bishops with nominal sees. These bishops perform auxiliary roles where a diocese is particular large or populous, or for historical reasons, or when the diocese otherwise cannot be served by a single bishop.

- Archdiocese of Sulthey

- Lord Archbishop of Sulthey : Cardinal Dr. Sebastian Williams

- Bishop of Frews : Cardinal Dr. Alfred Harris

- Diocese of Chepingstow

- Lord Bishop of Chepingstow : Cardinal Dr. William Laseby, Lord High Chancellour

- Bishop of Aldesey : Dr. Lochlan Riddel

- Diocese of Mast

- Lord Bishop of Mast : Dr. Edmund Widow-Goddering

- Diocese of Polton

- Lord Bishop of Polton : Cardinal Dr. Henry Cockstaff

- Bishop of Laveshot : Dr. Quentin Rhoming-Cecils

- Diocese of Staithway

- Lord Bishop of Staithway : Dr. James Hotham

Province of Limmes

- Archdiocese of Limmes

- Lord Bishop of Limmes : Cardinal Dr. David Coke

- Diocese of Scode

- Lord Bishop of Scode : Dr. Luke Mainthompson

- Diocese of Echester

- Lord Bishop of Echester : Dr. Phillip Michael

- Diocese of Lanchester

- Lord Bishop of Lanchester : Dr. Richard Cambright

- Diocese of Lendert and Cadell

- Lord Bishop of Lendert : Cardinal Dr. Alan Gough

- Bishop of Cadell : Dr. Walter Fitzcolling

- Diocese of Tow and St Cleaves

- Lord Bishop of St Cleaves : Cardinal Dr. Charles Franfield-Hamilton

- Bishop of Tow : Cardinal Dr. Peter Wylde, Lord High Almoner

- Diocese of Walecester

- Lord Bishop of Walecester : Cardinal Dr. George

Province of Rhise

- Archdiocese of Rhise and Hoole

- Archbishop of Rhise : Cardinal Dr. Nigel Molstham

- Bishop of Hoole : Dr. Stannon Haker

- Diocese of Keys

- Lord Bishop of Keys : Dr. Joseph Everard

- Diocese of Oxley

- Lord Bishop of Oxley : Dr. Archibald de Montdame

- Diocese of Corring (Rockleham) and Fivewells

- Lord Bishop of Corring and Fivewells : Dr. Simon Bickersleigh

- Diocese of Rhighton

- Lord Bishop of Rhighton : Cardinal Dr. Crispin de Asper

Each diocese is split further into archdeaconries, deaneries and parishes, administered by an archdeacon, a dean and a rector respectively. A parish is usually conterminous with a feudal manor, which are not to be confused with baronies, whilst a deanery is coterminous with a hundred.

Parish

A parish is the most local level of church organisation, roughly equivalent to a civil manor. Each parish has a benefice, the holder of which has the title of rector. The rector is appointed by the bishop on nomination by the patron of the parish, usually the lord of the manor. The rector is charged with the cure of souls in the parish, and is supported by the parochial tithes.

The benefice can also be appropriated by certain corporations such as a religious foundation in perpetuity. As the corporation is not itself capable of performing the rector's duties, it is bound to nominate a vicar who will discharge its spiritual obligations. The corporation as rector is entitled to the tithes, but a portion thereof must be given to the vicar.

The other officers of a parish are the parish clerk (acting as subdeacon at a high mess and responsible for the parish registers and administration), the verger (responsible for keeping the sacred vessels, moveable furnishings and vestments, keeping order in the church) and the sexton (responsible for keys to the church building, ringing the bells, and the physical upkeep of the church's fixed furnishings and of the churchyard).

Every parish has a parish vestry council, which have duties both ecclesiastial and civil. Two or more lay churchwardens are elected by the parish annually to represent their interests in the vestry. Many parishes, in addition to the parson, have a deacon. Many wealthy parishes have private chapels within the parish church with their own chaplain, usually established to say prayers for the dead and their families. Larger parishes also often have chapels-of-ease with their own parson, deacon, chapelry clerk and other officers.

This page is written in Erbonian English, which has its own spelling conventions (colour, travelled, centre, realise, instal, sobre, shew, artefact), and some terms that are used in it may be different or absent from other varieties of English. |